Introduction

Worldwide, anxiety, depression, disruptive and oppositional behaviors are amongst the most common social and emotional problems in childhood and adolescence (Erskine et al., 2016; Fosco et al., 2019), with prevalence ranging from 2.6% (Polanczyk et al., 2015) to 6.7% (Erskine et al., 2016). Among other factors, several studies have identified family functioning, parental (e.g., education, socioeconomic status, mental health, emotion-regulation) and child characteristics (e.g., age group and gender) as protective or risk factors for children’s social and emotional outcomes (Berryhill et al., 2018; Lee & McLanahan, 2015; Shelton & Harold, 2008; Sijtsema et al., 2014).

According to the family system framework, the family is an emotional system with interdependent elements, which undergoes constant changes across various developmental stages that require adjustment and reorganization (Minuchin, 1979). Family functioning encompasses difficulties (e.g., family reconfiguration, after parental divorce), strengths (e.g., skills, resilience, interpersonal, and social support), and communication (e.g., the connection of the whole system’s coexistence, being based on equality or difference) (Minuchin, 1979; Smock & Swartz, 2020; Stratton et al., 2010). Sources of stress may lead to difficulties in family functioning and can be a risk factor for child social and emotional functioning (Friesen et al., 2017). Strengths and communication are essential to avoid the adverse outcomes of stress (Minuchin, 1979) for a child’s social and emotional functioning (Agha et al., 2017; Carvalho et al., 2018; Fosco et al., 2019; Sijtsema et al., 2014).

The onset and the later development of children’s social and emotional problems have been positively associated with maternal psychopathology (Agha et al., 2017; Goergen et al., 2018), by exposing children to maladaptive behaviors (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Within the framework of third-wave cognitive-behavioral approaches, maternal emotion self-regulation may impact directly and indirectly (through maternal mental health) child SEB. Defined as a negative self-assessment and self-judgment of perceived failures and minor or inexistent errors (Castilho & Pinto-Gouveia, 2011b), self-criticism activates dominance-subordination strategies in reaction to social threat and predisposes individuals to negative emotions and psychopathology (Castilho et al., 2015), including depressive symptomatology and anxiety (Werner et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Research has found that maternal self-criticism is associated with internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children (Beebe & Lachmann, 2017; Casalin et al., 2014). Several authors (e.g., Werner et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019) have associated maternal self-criticism with adverse child outcomes, partly due to the link between self-criticism and psychopathology.

In contrast, self-compassion is an openness to oneself that encompasses three basic components: self-kindness (warmth and understanding), human condition (understanding own experiences of suffering as part of a larger human experience, rather than isolating or separating them), and mindfulness (being sensitive to the present moment, accepting rather than judging) (Neff & Davidson, 2016). These basic components have a protective role against the development and maintenance of psychopathology (Neff, 2003; Neff & McGehee, 2010). Studies have shown that maternal self-compassion is associated with better quality of life (Moreira et al., 2015; Neff and McGehee, 2010) and self-compassion (Carbonneau et al., 2020; Neff & McGehee, 2010) in children.

Present study

Literature on the impact of maternal emotion self-regulation strategies on child SEB is limited. Furthermore, family structures have increased in complexity in recent decades and maternal presence is predominant in most family configurations (Delgado & Wall, 2014).

Thus, the present study: (1) examined the associations between mother’s perceived child SEB (problems and prosocial behavior [PSB]) and maternal reported self-criticism, self-compassion, psychopathological symptomatology, and family functioning; (2) explored the differences in mothers’ perceived child SEB, depending on maternal, child, and family variables; and (3) analyzed the predictive role of maternal reported self-criticism and self-compassion on mother’s perceived child SEB. The following hypotheses were established: (1) mothers who perceive worse SEB among their children will also perceive more psychopathological symptomatology and self-criticism, less self-compassion, and worse family functioning; (2) mothers will perceive more child-related social and emotional difficulties if they have a personal history of psychiatric illness, less formal schooling, lower family income, and a non-nuclear family. Also, if their child is a young boy with early behavioral problems; (3) greater maternal self-criticism and lower maternal self-compassion will predict mother’s perceived child SEB.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 431 Portuguese biological mothers, aged between 25-59 years (M=39.37; SD=5.47). Most mothers hold a university degree (52.7%) and a medium income (67.7%), were married/cohabiting (80.0%), lived in a nuclear family (76.1%), and had two children (46.2%). Only 8.1% of the mothers reported a history of psychiatric illness. Children were aged 7 to 17 years (M=8.77; SD=3.87; 4-5 years: 26.0%; 6-10 years: 42.0%, 11-14 years: 21.8%; 15-17 years: 10.2%). The percentage of children of each sex (boys: 55.5%) was almost comparable.

Measures

Beyond a sociodemographic form, mothers completed the following self-report questionnaires:

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire - Parent’s Version (SDQ; Goodman, 1997; Portuguese version: Fleitlich et al., 2005): This 25-item questionnaire assesses five dimensions, composed of five items each: emotional symptoms (ES), behavior problems (BP; e.g., “often lies or cheats”), hyperactivity/attention deficit H-ADD), difficulties in peer relationships (DPR), and prosocial behavior (PSB; e.g., “shares readily with other children, for example, toys, treats, pencils”). Each item is answered using a Likert scale, ranging from 0 (Not True) to 2 (Very True). The total score ranges from zero to 40 (more behavior problems) and excludes PSB. Cronbach’s alpha was .76 for total difficulties in original studies (Smedje et al., 1999), .74 in the Portuguese population (Conceição & Carvalho, 2013), and .82 in this study. Additionally, the PSB subscale presented a Cronbach’s alpha of .76 in this study.

Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation (SCORE-15; Stratton et al., 2010; Portuguese version: Vilaça et al., 2014) is a 15-item Likert questionnaire with five response options, ranging from 1 (Describes us very well) to 5 (Describes us not at all). It assesses family functioning and therapeutic change, according to three dimensions: family strengths (FS), family communication (FC), and family difficulties (FD). The total score ranges from one to five, and higher scores indicate worse family functioning. The Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale was .89 for the original study (Stratton et al., 2010) and .84 for the Portuguese study (Vilaça et al., 2014). In our study, Cronbach’s alpha was .84 for the total scale and .78, .77, and .76 for FS, FC, and FD, respectively.

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983; Portuguese version: Canavarro, 1999) is a 53-item questionnaire that assesses psychopathological symptomatology through nine dimensions (e.g., somatization, depression, anxiety) and three global indexes. Each item is answered, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely). In the present study, we used the Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI; an average of all reported symptoms) with scores over 1.7 suggestive of emotional disturbance (Canavarro, 1999). Cronbach’s alpha of the nine dimensions ranged from .71-.85 in the original study (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), .62-.80 in the Portuguese study (Canavarro, 1999), and .86-.75 in the present study.

Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS; Gilbert et al., 2004; Portuguese version: Castilho & Pinto-Gouveia, 2011a) is a 22-item questionnaire, answered using a 5-point Likert ranging from 0 (I am not like this) to 4 (I am extremely like this). This questionnaire assesses how individuals self-criticize and self-reassure themselves when things go wrong, using three subscales. In the present study, we used the sum of the inadequate self (10 items) and hated self (three items) subscales. The total score ranges from 0-52, with higher scores representing more self-criticism toward the self (Castilho & Pinto-Gouveia, 2011a). Cronbach’s alphas were high in the original version (inadequate self: α=.90; hated self: α=.86). In the Portuguese version, Cronbach’s alphas were .89 for inadequate self and .62 for hated self. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha of the composite (inadequate self and hated self) was .88.

Self-Compassion Scale (SELFCS; Neff, 2003; Portuguese version: Castilho & Pinto-Gouveia, 2011b) consists of 26 items, answered in a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 - Almost Never to 5 - Almost Always). This questionnaire assesses self-compassion, using six subscales (self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification). Higher total scores represent greater self-compassion. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was

.92 in the original version, .89 in the Portuguese adaptation (Castilho & Pinto-Gouveia, 2011b), and .91 in the present study.

Procedures

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Miguel Torga Institute of Higher Education (CE-P19-21). Inclusion criteria in the present study were being a biological mother of a child aged 4-17 years. Exclusion criteria were being an adoptive mother and non-Portuguese nationality. When mothers had more than one child aged 4-17 years, they were asked to complete the questionnaires considering the oldest one). A community-based recruitment strategy was used. Specifically, the link to the informed consent (explaining the research objectives and ethical procedures) and the online questionnaires (available in the Google Forms platform) were disseminated through social networks and by e-mail. Furthermore, 13% (n=56) of the participants were given hard copies of the written informed consent and questionnaires in a closed envelope, to ensure confidentiality. The questionnaires took approximately 15 minutes to answer and were available online for three months, from January to April 2019.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics (v.25). Parametric tests were used, since asymmetry and kurtosis values were below two and four. For the first aim, Pearson’s correlations were calculated. With respect to the second aim, Student t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc tests were performed. For the third aim, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed. Sample size, normality, linearity, multi-collinearity and homoscedasticity assumptions were met. The inexistence of outliers (except for two cases) was also ensured. Mother, child, and family variables were entered as control variables at Step 1, maternal psychopathological symptomatology and family functioning at Step 2, and self-criticism, self-compassion as final predictors of children’s behavior problems (total SDQ) and of children’s pro-social behavior (PSB-SDQ).

Effect sizes were interpreted as: low/small (r=.10-.29, d=0.20-0.49); moderate/medium (r=.30-.49, d=0.50-0.79); and high/large (r=.50-1, d=0.80-1.29) (Cohen, 1988). Cohen’s eta square values were interpreted using the reference values of Espírito-Santo and Daniel (2018) and the respective Bonferroni adjustment (three groups: p<.017; four groups: p<.0125).

Results

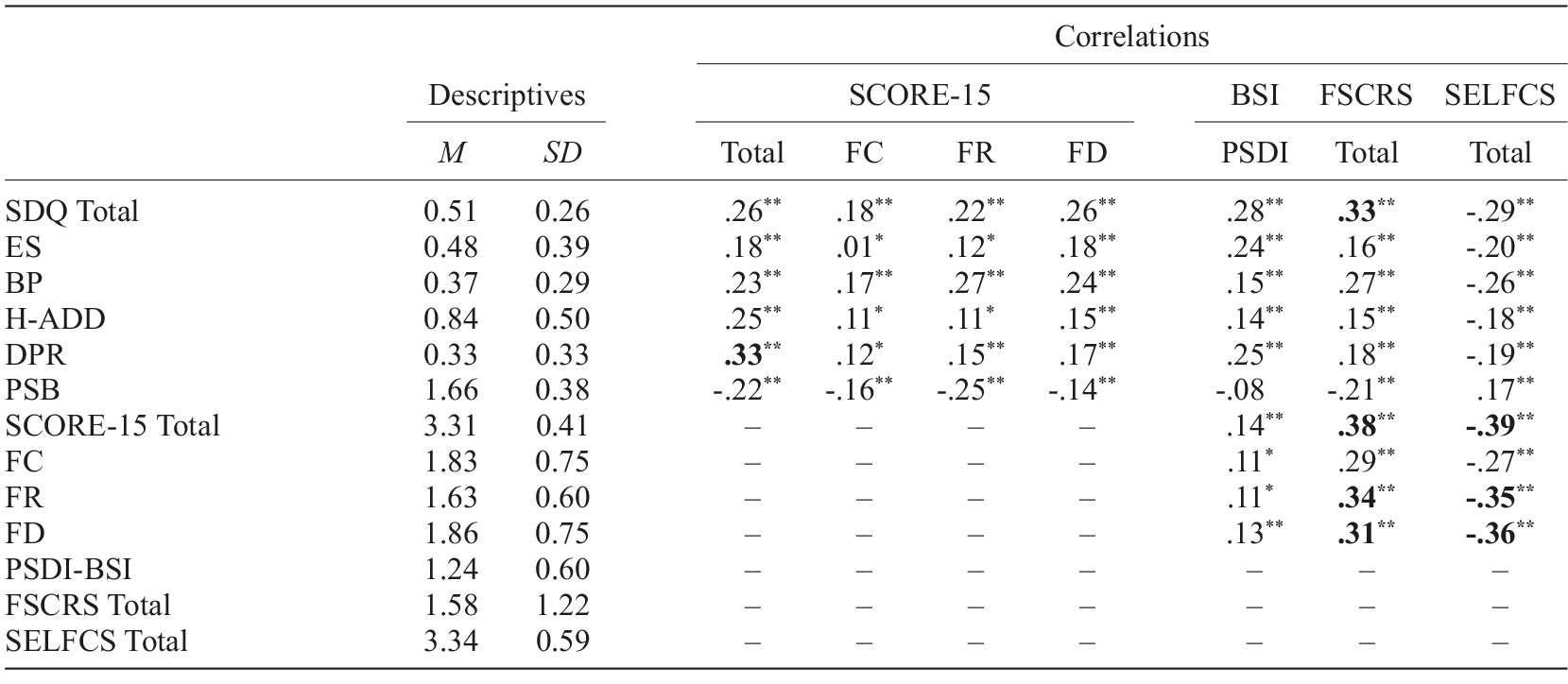

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviations) and correlations of the study variables. As shown in Table 1, we found moderate correlations of: difficulties in peer-relationships (SDQ) with family functioning (total SCORE-15) (r 2 =10.9%); child total behavior problems (total SDQ) with self-criticism (r 2 =10.9%); family functioning with self-criticism (r 2 =14.4%) and self-compassion (r 2 =15.2%); family resources (SCORE-15) with self-criticism (r 2 =11.6%) and self-compassion (r 2 =12.3%); and family difficulties (FD-SCORE-15) with self-criticism (r 2 =9.6%) and self-compassion (r 2 =13.0%). Children’s prosocial behavior (PSB-SDQ) did not correlate significantly with maternal psychopathological symptomatology (PSDI-BSI).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviations) and Pearson correlations between mother’s perceived child’s social and emotional behaviors, family functioning, maternal psychopathology, self-criticism and self-compassion

Note. N=431. SCORE-15=Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation; SDQ=Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; ES=Emotional Symptoms; BP=Behavior Problems; H-ADD=Hyperactivity and Attention Deficit Difficulties; DPR=Difficulty in Peer Relations; PSB=Pro-Social Behavior; FC=Family Communication; FD=Family Difficulties; FR=Family Resources; FSCRS=Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale; SELFCS=Self-Compassion Scale; PSDI-BSI=Positive Symptom Distress Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory. Moderated correlations are highlighted in bold. * p<.05; ** p<.01.

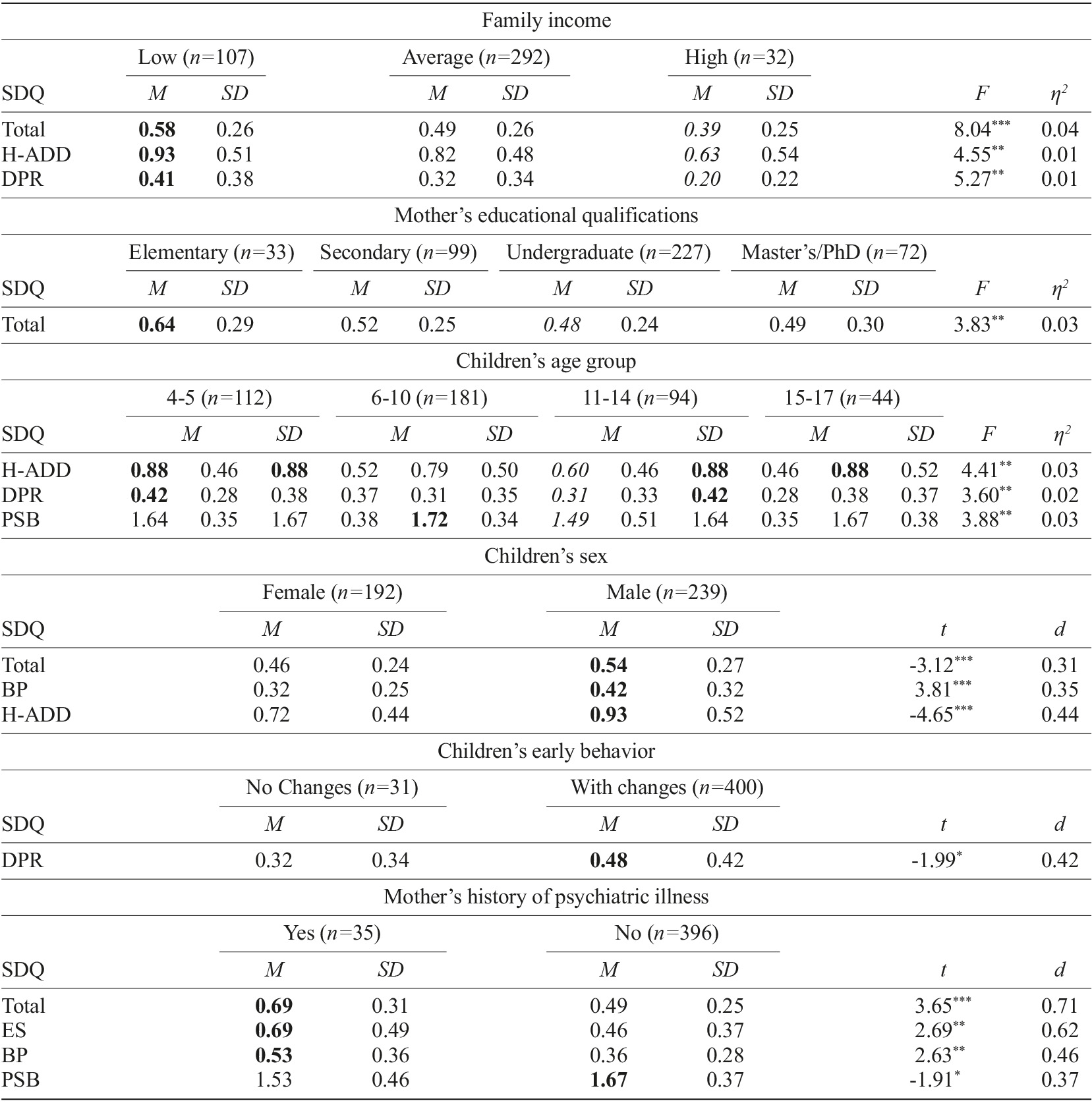

Table 2 displays statistically significant differences in SQD scores, according to the mother, child and family characteristics. Tukey’s post-hoc tests with Bonferroni correction showed that mothers with low family income perceived that their children reported higher total SDQ, hyperactivity/attention deficit, and difficulties in peer relations. Mothers with elementary school education identified more problems in their children (total SDQ) than those with a college degree. Mothers with a history of psychiatric illness described more social and emotional problems (total SDQ, emotional problems, behavioral problems) and less prosocial behavior in their children than those who did not report such problems. We did not find any differences based on family structure (nuclear, monoparental and reconstructed).

Table 2 Differences in SDQ results according to the mothers, children and family characteristics

Note. N=431. SDQ=Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; BP=Behavior Problems; DPR=Difficulty in Peer Relations; ES=Emotional Symptoms; H-ADD=Hyperactivity and Attention Deficit Difficulties; PSB=Pro-Social Behavior. The highest values are highlighted in bold. Italic letters denote significant differences (p<.017 for 3 groups or p<.0125 for 4 groups) between pairwise comparisons. * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** p<.001.

With respect to children’s characteristics, mothers reported that children aged 4-5 and 6-10 years displayed more hyperactive and attention deficit behaviors than those aged 15-17 years. Compared with those aged 15-17 years, mothers perceived that children aged 4-5 years had more difficulties with peers, whereas children aged 11-14 had more prosocial behaviors. Boys were perceived as having more overall social and emotional problems, behavioral problems, and attention deficit hyperactivity than girls. Lastly, children with identified early-onset behavioral changes were perceived to have more difficulty in peer relationships than children with no identified early-onset changes.

Maternal self-regulation strategies as predictors of children’s behavior problems and pro-social behavior

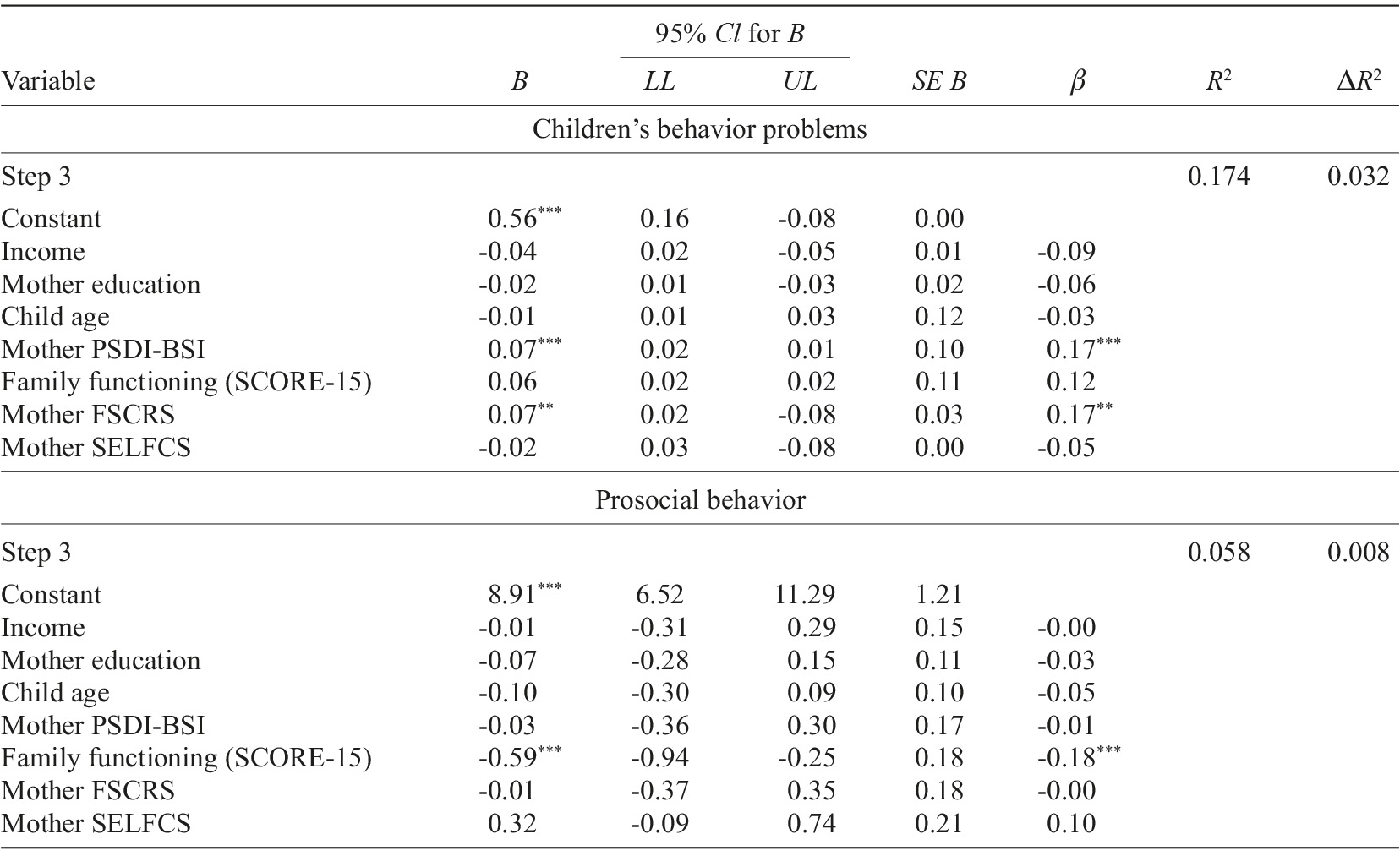

With respect to child’s behavior problems, mother’s reported family income, maternal education and child age (step 1, F (2,423)=6.04; p<.001) only explained 4.1% of the variance. The introduction of mother’s psychopathology and family functioning (step 2, F (2,423)=14.10; p<.001) and the introduction of maternal reported self-criticism and self-compassion (step 3, F (2,423)=8.14; p<.001, R 2 adjusted =.16) significantly increased the explained variance of the model. The only significant predictor in the final model was maternal self-criticism (Table 3).

Table 3 Multiple hierarchical regression results of children’s socioemotional behavior

Note. CI=confidence interval; LL=lower limit; UL=upper limit; SCORE-15=Systemic Clinical Outcome and Routine Evaluation; FSCRS=Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale; SELFCS=Self-Compassion Scale; PSDI-BSI=Positive Symptom Distress Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory. * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** p<.001.

Regarding prosocial behavior, a mother’s reported family income, maternal education and child’s age (step 1, F (2,425)=0.50; p>.05) only explained 0.4% of the variance. After including the maternal psychopathological symptomatology and family functioning (step 2, F (2,425)=4.52; p<.001) and self-criticism and self-compassion (step 3, F (2,423)=1.72; p=.180, R 2 adjusted=0.04), none of the latter variables made a significant contribution to the final model (Table 3).

Discussion

In line with our first hypothesis, the results showed that mothers who have less psychopathological symptomatology, are less self-critical and more self-compassionate perceived fewer behavioral difficulties in their children. These results are consistent with prior studies, showing that maternal mental health problems, self-criticism and worse family functioning are associated with behavioral and emotional problems in children (Agha et al., 2017; Beebe & Lachmann, 2017; Casalin et al., 2014; Fosco et al., 2019; Plass-Christl et al., 2017; Prioste et al., 2019; Weijers et al., 2018; Wiegand-Grefe et al., 2019). The associations between maternal self-criticism and child’s social and emotional problems may be explained by several factors. First, high levels of parental self-criticism have been found to play a role in fostering negative affectivity in a child’s early development stages through intergenerational transmission mechanisms (Casalin et al., 2014). Second, the associations between maternal self-criticism and maternal psychopathology might also partially explain our findings (e.g., Werner et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Lastly, the relationship of maternal mental health and self-regulation with children’s socioemotional behaviors is complex and possibly bidirectional. Studies have found that children’s behaviors may contribute to maternal psychopathology (Xerxa et al., 2021) or reduced levels of positive parenting that, in turn, increase children’s externalizing problems (Serbin et al., 2015). Furthermore, worse family functioning was also associated with more maternal psychopathological symptoms and higher levels of self-criticism. These findings are in line with prior research, showing that parental mental illness is associated with higher levels of family dysfunctionality, which may, in turn, increase the probability of psychological problems in children (Agha et al., 2017; Wiegand-Grefe et al., 2019).

Conversely, we found negative associations between maternal self-compassion, better family functioning and children’s social and emotional problems. Prior research has shown that parents who perceive more stable family functioning and are more self-compassionate display more adaptive parenting behaviors (care and support), respond to children’s needs more adaptively (Gouveia et al., 2016) and provide them more opportunities for emotional and behavioral growth (Moreira et al., 2015).

With regard to our second aim, our findings support most of our second hypothesis being consistent with prior research, showing that mothers identified more behavioral difficulties in boys (Machado & Diogo, 2017) and more prosocial behaviors in older age groups, reflecting possibly the advances in physical, cognitive, and relational development (Eisenberg & Shell, 1986; Van der Graaff et al., 2018). Despite the differences in groups’ sizes, mothers reported that children who had early behavior problems had more difficulties with peers. This supports the idea that behavior problems are stable over time (Eisner & Malti, 2015). Although there are variations and child characteristics (e.g., irritability) are also important (Campos et al., 1989), the developmental psychopathology approach establishes that behavior problems often emerge in childhood and are exacerbated by the quality of early parent-child relationships (Fosco et al., 2019; Patterson et al., 1989).

However, our study did not find differences in child SEB, according to family structure. Studies have found that parental separation (e.g., Friesen et al., 2017) or the transition to a reconstituted family (e.g., Anderson & Greene, 2013; Costa & Dias, 2012; Jensen & Shafer, 2013) may be perceived to impact negatively on children’s social and emotional behaviors. However, the negative impact of these family stressors on children’s social and emotional appears to depend on other factors, such as the quality of parental relationships post-separation, the transition to a different family structure, changes of residence, school and family support network (Friesen et al., 2017). In fact, research has found that parents in nuclear families devote more time to their children than parents in single-parent and reconstituted families (Fallesen & Gähler, 2020) and that parental separation is associated with lower levels of parental sensitivity and emotional warmth/support, higher reactivity, and increased use of punishment (Friesen et al., 2017). Thus, family functioning seems to be more important than the family structure in predicting a child’s social and emotional behavior (Lin et al., 2019; Simões et al., 2013).

With respect to maternal sociodemographic characteristics, our findings are consistent with studies showing that mother’s reported higher income and education are associated with lower levels of children’s depression, opposition problems and mental health problems (Ahn et al., 2019; Anselmi et al., 2010; Gan & Bilige, 2019; Sijtsema et al., 2014). More highly educated parents may have higher educational expectations for their children, stimulating them through play activities and affective behaviors (Drajea & Carmel, 2014).

In line with our hypothesis, maternal self-criticism was the main predictor of mothers’ perceived child social and emotional difficulties. Neither maternal self-criticism nor self-compassion stood predicted mother’s perceived child prosocial behavior. These results corroborate previous research showing the negative impact of maternal self-criticism (e.g., Wickersham et al., 2020) on children’s behavior, whereas maternal self-compassion has been shown to contribute positively to children’s behavior (Gouveia et al., 2016).

Limitations and future directions

Analyzing the mother’s perspective on a child’s behavior and family functioning and excluding the father’s and child’s perceptions may have hindered a more comprehensive view. Also, parental perceptions of their children’s behavior and may not correspond to actual behaviors. The cross-sectional design does not allow causal inferences to be made. Although it is expected that its members take time to adapt, we did not evaluate the length of the family typology. Also, the difference in the groups’ size limits the conclusions that can be drawn. Moreover, the results should be discussed considering children’s ages. Finally, considering that the SDQ and the SCORE-15 are multidimensional measures, MANOVAs should be performed. However, results from MANOVA may be more ambiguous than ANOVA, and frequently MANOVA is less powerful than separate ANOVAs (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2014).

Despite these limitations, this study may have contributed to a better understanding of the relationships between family functioning, maternal psychological variables and mother’s perceived child behaviors. Future research could address children’s development over time concerning different family and contextual variables, include interviews to assess the perspective of all family members and children’s perspective on the family and their behaviors, and collect more detailed data on child and parental characteristics (e.g., parents’ personality, children’s temperament, physical health) that may have an impact on parental behavior.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings emphasize that it is critical to prevent and treat maternal psychopathology, by promoting self-compassion and reducing self-criticism, and to make available positive parenting programs that promote family skills, strengthen parents’ competencies, respect children’s best interests and enhance their healthy development (Kirby, 2017), especially for low-income and educated families. In fact, preventive intervention in families with parental mental illnesses leads to a reduction of 40% in the risk of psychological illness and symptoms in children and impedes mental illness transmission (Wiegand-Grefe et al., 2019). Additional support from parental counseling services (Nowak & Heinrichs, 2008) may contribute to promote parental mental health and parenting skills, by integrating mindfulness-focused approaches or compassion-focused therapy as effective interventions (McKee et al., 2017). This investment in maternal mental health might not only directly contribute to children’s healthier developmental trajectories, but also have a predictable repercussion in economic terms, by reducing the demand for health care services.