Introduction

Tourism has been an engine of economic growth in Europe since the end of the Second World War. Today, urban tourism is the industry’s most dynamic segment. Tourism is a central component of the economy in urban territories, with strong impacts on social life and the natural environment. As such, its relevance and interest to public policy is not surprising.

Recent academic literature has largely focused on the analysis of urban tourism, framed particularly as a neoliberal, political and economic response to structural change in the economy. There is an urgent need to analyze tourism public policy at the local level, particularly its underlying rationale, roles, and activities (Dredge, 2010; Shone et al., 2016). Thus, this paper intends to examine tourism policy at a local scale in Portugal, taking Lisbon and Porto (the two largest cities) as a case study.

Our study employs a multi-scale perspective, because tourism policy in Portugal is defined at the national and regional scales. In addition, a descriptive and exploratory approach has been applied, which seeks to understand the genesis and development of this policy as well as its operation, goals, strengths, and weaknesses1.

After a brief theoretical introduction to the concept of tourism policy, we will conduct a historical analysis of its development, main organizational and administrative tools, as well as the main tourism plans and programs in Portugal from the 20th century. We will then proceed with an in-depth analysis of tourism policy from the 21st century, at a national and municipal level in Lisbon and Porto, cities that have witnessed rapid, intensive growth in tourism in recent years. The next section seeks to compare tourism policies in the two cities. The last section discusses the need to develop a more sustainable combination of tourist activities with other territorial uses and activities, bearing in mind the interests and needs of the various urban actors.

What is meant by public policy in tourism?

Tourism is a complex activity, involving an array of agents and activities (Scott, 2011). It has the potential to produce direct, indirect and induced impacts (positive and negative) on the territories, amongst which job creation and wealth generation are the most frequently mentioned positive impacts (Andereck et al., 2007). This potential for economic development, on the one hand, and the existence of market failures and imperfections, on the other, are the drivers of public policy related to the tourism sector (Ruhanen, 2013). They aim primarily to provide a more efficient allocation of tourism public goods and services and contribute to the development of tourist destinations.

The main market failures include tourism public goods such as tourism promotion, infrastructure/equipment, coordination and planning, externalities, natural monopolies, and information asymmetry (Andersson & Getz, 2009).

Since the mid-twentieth century, there have been several changes in how policy and its tools are generally devised in Western liberal democracies, and specifically in the context of tourist activity. With the spread of neoliberalism in recent decades, globalization, and the new public management, the role of governments as fundamental institutions in the definition and guarantee of the public good has shifted. At the end of the 20th century, the government was called upon to play the role of mediator in economic activity (Stevenson et al., 2008), fostering the proliferation of public-private partnerships and the development of collaborative planning (Hall, 2011). More recently, several authors have identified a growing neoliberal vision of public policy, namely in tourism, blurring the line between public and private interests (Bramwell, 2011; Dredge, 2010). Hence, government performance has become notably intertwined with that of the private sector. Public resources are channeled to promote the private sector, more than that of “third sector” organizations, and the involvement of the community in promoting the common good, both social and environmental, has been neglected (Dredge & Jenkins, 2013; Swanson & Brothers, 2012).

Public policy can be understood as a set of governmental discourses, decisions, and practices, at times in collaboration with private and social actors, to achieve different goals related to tourism (Velasco, 2017). It can have different temporalities (i.e., short term, mid-term, long term) and be developed at different geographic scales (i.e., supranational, national or local). In Portugal, successive governments have adopted tourism as a priority area of intervention in their programs. Portuguese legislation in this area links the national and local scales through the participation of municipalities in regional structures. The following sections will analyze the evolution of policies at the national and local levels, to understand to what extent they have responded to the challenges of their time.

The evolution of tourism public policy in Portugal in the 20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, Portugal discovered the benefits of tourism as an economic activity. The Sociedade Propaganda de Portugal was created in 1906 upon private initiative, charged with the task of promoting tourism. This Society organized the 4th Tourism Congress in Lisbon (1911), giving rise to modern tourism in Portugal (Costa, 2015). In the same year, the government created the Tourism Council and the Tourism Department, transferring the Society's responsibilities to the government sector. Portugal thus became the third country in the world, after Australia (1909) and France (1910), to establish public bodies dedicated to tourism management.

Despite the initial pioneering spirit, tourism was not able to take root in Portugal as a relevant economic activity (Cunha, 2012). Tourism policy focused primarily on the development and promotion of a reduced number of products and territories with a strong nationalist dimension.

After the Second World War, tourism became a mass phenomenon at the international level, but this was not the case in Portugal initially (García, 2014). Later, several reforms created the legal basis for the future development of tourism, such as the first Tourism Framework Law (Law No. 2082) published in 1956, which defined state responsibilities in terms of tourism and created the Tourism Fund.

Although in an unplanned way, the number of arrivals in Portugal doubled in 1964, reaching one million visitors, and tourist revenue increased by 63%. In this period, a chapter on tourism was introduced into the Portuguese Development Plans, on which the government’s economic planning depended. However, they did not define a development model or policy framework for spatial planning (Costa, 2015). Following the 1974 revolution, Portuguese tourism experienced a period of crisis, for internal reasons. Throughout the 1970s, the sector lacked any type of tourism policy or strategy.

In the 1980s, economic and social changes emerged worldwide and led to the New Age of Tourism (Fayos-Solá, 2004), characterized by a less standardized, more fragmented and competitive tourism. Faced with this new paradigm, tourism strategies and policies were adapted and shifted towards the integration of tourism development in all its related activities. It was in this period that Portugal became an international tourist destination, going from 2.7 million tourists in 1980 to 8 million in 1990 (Cunha, 2012). However, this growth contributed to the aggravation of several problems, particularly: a) the lack of coherent urban planning, leading to negative environmental impacts, accompanied by strong links between tourism and real estate; b) dependence on a reduced number of markets; c) the symptoms of depletion of the “sun and beach” label and lack of diversification; d) the concentration of tourist activity in Lisbon, Madeira and the Algarve (Garcia, 2014).

At this time, tourism was included in spatial planning policy, with the first National Tourism Plan for the 1986-1989 period. However, the programs and strategies devised to adapt the existing development model to the characteristics of the New Age of Tourism proved to be insufficient and the country faced stiff competition from other destinations (Cunha, 2012). In the 1990s, following the Spanish model, Portugal invested in attracting major international events (e.g., in 1998, Lisbon International Exhibition - EXPO '98; in 2001, Porto European Capital of Culture) (García, 2014), whose organization became a means to establish destinations worldwide and an engine for tourism and economic development.

As we have seen, tourism public policy in Portugal did not experience consistent development for most of the 20th century. It was in the 1980s that tourism recorded notable growth and was gradually included in spatial planning strategies. However, no measures were taken to avoid or mitigate negative effects on the environment and urban landscape. In the 1990s, Portugal definitely gained international prospects and tourism became a driving force for economic and territorial growth.

Tourism public policy in Portugal in the new millennium

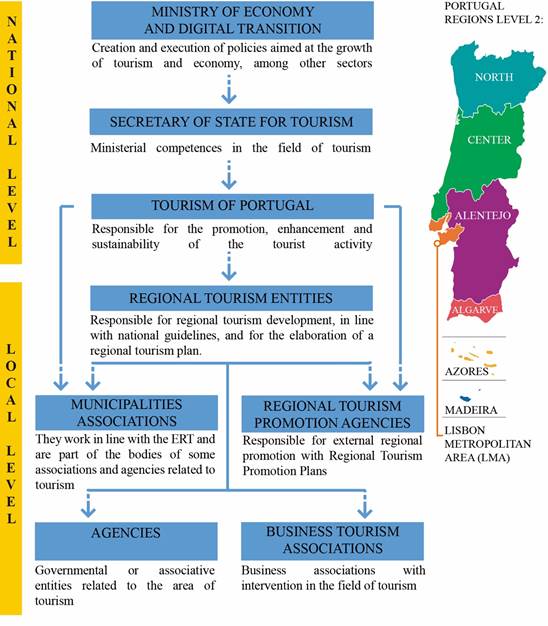

The implementation of specific policies for the tourism sector in Portugal is carried out by the Ministry of Economy and Digital Transition, with the collaboration of the Secretary of State for Tourism. Tourism of Portugal (Turismo de Portugal, TdP) is the body responsible for managing and planning tourism at a national level. It coordinates with five Regional Tourism Entities (Entidades Regionais de Turismo, ERT), coinciding with the NUTS II2 (mainland Portugal)3 (Decree-Law No. 67/2008). At the regional level, the Regional Tourism Promotion Agencies (Agências Regionais de Promoção Turística, ARPT) are responsible for promoting tourism. Furthermore, associations of municipalities, with regulatory and support powers in the sector, participate in the spatial organization of tourism (Costa, 2015), as well as several governmental and associative agencies and business tourism associations (Figure 1). The Framework Law for Tourism Public Policy, drafted in 2009 (Decree-Law No. 191/2009), establishes the foundation for tourism public policy and defines the tools for its implementation.

From a planning perspective, the National Strategic Tourism Plan (Plano Estratégico Nacional de Turismo, PENT) was approved in 2007, which defined the basis for the growth and sustainable development of tourism until 2015 (Council of Ministers Resolution No. 53/2007). The PENT aimed to stimulate tourism growth, considered as a strategic sector. The preamble states that tourism is a relevant activity for sustainable development in environmental, economic and social terms. Urban, environmental and landscape quality is seen as a “fundamental component of the tourist product to enhance/qualify Portugal as a destination” (Council of Ministers Resolution No. 53/2007, p. 2171). It is, therefore, regarded not from the perspective of sustainability, but as an element to improve the product.

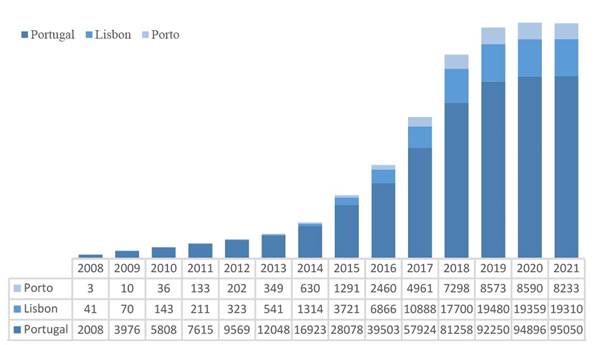

The PENT's quantitative goals were in line with the data collected over the 2010s. For example, a 9% increase in revenue was achieved, exceeding 15 billion euros in 2015. This year, revenue reached 11.4 billion euros (INE, 2016). In this decade, the sector grew considerably, representing 15.9% of the GDP in 2019 (INE, 2020), while the number of guests doubled between 2009 and 2019 (Figure 2).

The main goal of the current national strategy, Tourism Strategy 2027 (Estratégia Turismo 2027, ET27), launched in 2017, is to make Portugal an “increasingly competitive destination”, as well as increase revenue and tourist demand throughout the country (TdP, 2017, p. 44). It shows concern not only with the production chain, but also with the reality in which tourism operates, highlighting opportunities, but also threats. In line with ET27, a 20-23 Tourism + Sustainable Plan (TdP, 2020) has been prepared, which aims to contribute to the revival of the tourist activity after the COVID-19 pandemic, fostering recovery based on environmental sustainability.

Source: Own elaboration based on data available at www.pordata.pt

Figure 2 Number of guests in millions in Portugal, Lisbon and Porto

Implemented in 2021, the Reactivate Tourism | Building the Future Action Plan (TdP, 2021) is intended to put the sector back on the path of pre-COVID-19 growth, as well as to create mechanisms for more sustainable, responsible, competitive, and resilient tourism. The Plan is composed of specific short-, mid- and long-term actions, and includes funds for the capitalization of companies, credit lines and financing, among other measures.

Also following the pandemic, the Adapt Tourism Program (Normative Ordinance No. 24/2021) was created, targeted at the recovery of businesses and in adapting their work organization, customer relations and supplier chains to the post-COVID-19 context.

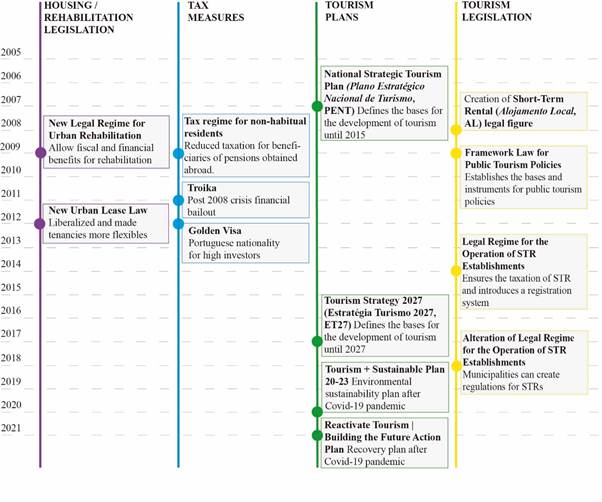

The tools described so far are part of a broad framework of government investment in marketing strategies aimed at attracting transnational capital. Specially in the post-2008 crisis period, tourism and foreign investment in real estate were seen as a solution to the recession (Mendes, 2017). In order to better understand this situation, some legislative tools linked to tourism will be examined below (Figure 3).

The link between tourism and real estate investment is not new. The construction of second holiday homes is part of the development of some tourist destinations since the 1980s, specially in Portugal’s coastal areas (Cunha, 2012). At the beginning of the 21st century, the so-called “residential tourism” was considered a strategic product in the PENT. Currently, there are several resorts in Portugal offering part of their accommodation to retired foreigners looking for a Mediterranean climate and an affordable cost of living. In 2009, a special tax regime for non-habitual residents was created (Decree-Law No. 249/2009), targeting foreign pensioners, among others.

In 2008, to regulate short-term rentals (STRs), the government introduced the legal figure of “local accommodation” (alojamento local) applied to the provision of temporary accommodation services in houses, apartments, lodging establishments, and rooms (Decree-Law No. 39/2008). In 2014, the Legal Regime for the Operation of STR Establishments (Regime Jurídico da Exploração dos Estabelecimentos de Alojamento Local, RJEEAL) was passed (Decree-law No. 128/2014), ensuring STR taxation and introducing an online registration system.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 3 Chronological scheme of the main national legislative measures directly or indirectly related to tourism

At the same time, the New Legal Regime for Urban Rehabilitation (Decree-Law No. 307/2009) provided fiscal and financial benefits, thus attracting capital to the real estate sector. However, this regime limited urban rehabilitation operations to mere physical actions, instead of promoting integrated rehabilitation processes.

To rebalance public accounts after the 2008 crisis, in 2011 the Portuguese government signed a bailout plan with the “Troika” (European Commission, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund). Consequently, financial austerity policies and structural reforms were introduced (Mendes, 2017), including the 2012 New Urban Lease Law (Law No. 31/2012), which liberalized and made renting more flexible.

Although this period witnessed the progressive depletion of traditional mass tourism destinations, renewal projects proliferated, such as of historic urban centers with potential for tourist activity, capital accumulation, and real estate speculation (Barata-Salgueiro, Mendes & Guimarães, 2017). Thus, the New Legal Regime for Urban Rehabilitation and the New Urban Lease Law were fundamental in fostering the conversion of long-term rental apartments into STR. In fact, the number of STRs in Portugal increased rapidly since 2014, reaching 95.050 units in 2021 (Figure 4).

Source: own elaboration based on data available at www.travelbi.turismodeportugal.pt

Figure 4 Evolution of the number of STR records in Portugal, Lisbon and Porto

The success of STRs is linked to their efficiency and flexibility at the market level. STRs can be responsible for transforming housing into financial products, contributing to touristification processes that drive the local population out and reduce the number of long-term rental apartments (Cocola-Gant & Gago, 2019;). The European Parliament recognized that STR growth “is taking housing off the market and increasing prices, which could have a negative impact on living conditions in urban and tourist centres”, and recommends that national and local authorities develop policies to restrict their operation (European Parliament, 2021). In 2018, the pressure of the STRs on some territories (e.g., Lisbon and Porto) led several municipalities to set limits on the use of housing for tourism purposes (Law 62/2018), through a “permits with restrictions” approach (Nieuwland & van Melik, 2020).

At the same time, focus shifted also to non-permanent residents, such as digital nomads (Montezuma & Mcgarrigle, 2018) or international students (Malet Calvo, 2013). In ET27, the “Living - Viver Portugal” label is considered one of the strategic assets of national tourism, aimed at investors, foreign students and researchers seeking residency in Portugal, who supposedly “contribute to a multicultural environment and an entrepreneurial ecosystem” (TdP, 2017, p. 49).

In 2012, the Golden Visa scheme was created (Law No. 29/2012), granting residency in Portugal to investors who purchased real estate, invested in rehabilitation, transferred capital, or created at least ten jobs. The program has essentially worked through real estate investments: by 2021, 93.5% of visas were granted for the purchase of real estate (SEF, 2021). The Golden Visa scheme has attracted global capital to the real estate market with the consequent increase in housing prices (Mendes, 2017). More recently, Decree-Law No. 14/2021 changed how Golden Visas are granted, directing investments to the more vulnerable inland territories. Visas for real estate investment for housing purposes in Lisbon, Porto and the coastal areas have been cancelled. But these limitations do not apply to non-residential real estate, which means investments are still allowed across the country. Thus, it does not appear that these amendments will bring about substantial changes.

The post-2008 economic recovery model was based on the pillars of urban tourism, foreign investment and the financialization of real estate, generating rapid growth with consequences in terms of environmental, social and economic sustainability (Mendes, 2021). The pandemic has exacerbated the contradictions of this model and the social inequalities it has caused (Mendes, 2021). We have seen how tourism public policies have been designed and implemented in Portugal at different geographic scales, both closely related to the tourism sector, as well as more comprehensive ones, within the scope of spatial planning and development. Thus, national policies are aligned with those designed by the ERTs, devised within the regions and metropolitan areas. The next sections will discuss the tourism public policies implemented in Lisbon and Porto by the respective City Councils, as well as their coordination with spatial planning policies.

Public policy at the municipal level in Portugal

In the last three decades, tourism has been systematically included in public planning policies in Lisbon and Porto, the two largest Portuguese cities, articulated with other spatial planning policies at different territorial scales. The next sections are dedicated to the analysis of these policies in the two cities.

5.1. Tourism in public policies in Lisbon

Tourist activity gained importance in Lisbon in the 1990s when the industrial city became an urban landscape designed for mass consumption (Malet Calvo, 2013) and the “Lisbon brand” was launched through the organization of mega-events. The city was thus transformed into an international tourist destination. Later, the economic crisis of 2008 legitimized the focus on tourism as a panacea for the social and urban crisis (Mendes, 2017).

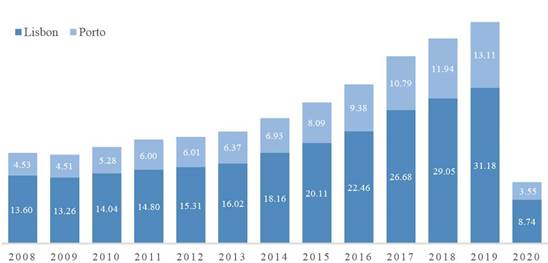

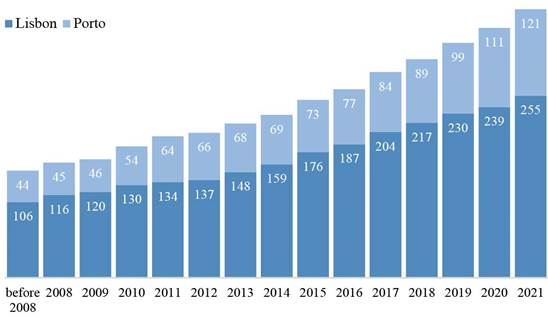

In the 2010s, tourism grew exponentially. In 2019, Lisbon achieved the following numbers: more than 10 million guests (Figure 2); more than 31 million passengers at the Lisbon airport (Figure 5), and more than 575 thousand at the port (TdP, 2011-2019). The hospitality offer grew as well, reaching 19.480 STR registrations (Figure 4) and 230 hotels (Figure 6) in 2019.

Source: own elaboration based on data available at www.pordata.pt

Figure 5 Passenger traffic (in millions) at the Lisbon and Porto airports

elaboration based on data available at https://registos.turismodeportugal.pt

Number of hotels in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA) and in Lisbon

Although there is no municipal body in charge of tourism, the City Council presides over the Lisbon Tourism Association - Visitors & Convention Bureau (Associação do Turismo de Lisboa, ATL), a non-profit private association of public interest, responsible for tourism development, the promotion of the city and the region, among other activities. To foster cooperation between the municipal and regional levels, ATL collaborates with the Lisbon Regional Tourism Entity (Entidade Regional do Turismo - Região de Lisboa, ERT-RL), responsible for tourism development in the Lisbon Regional Tourism Area (which coincides with the Lisbon Metropolitan Area). ATL and ERT-RL jointly draw up strategic plans for tourism development in the municipality of Lisbon and in the region.

In terms of spatial planning, in the early 2000s, the main goals of the Lisbon City Council’s 2002-2012 Strategic Vision (Visão estratégica 2002-2012) were to qualify and modernize the city and raise it to the ranking of the best cities to live, work and invest. Tourism was one of the activities envisaged to achieve these goals (Mangorrinha, 2009), in line with those defined at the regional level in the Strategic Lisbon Tourism Plans for 2007-2010 (TLx10) and 2011-2014 (TLx14), and at the national level in the PENT. The TLx10 intended to bolster the region's international reputation and growth, while the TLx14 established Lisbon as a “destination in the panorama of European capitals with greater tourist intensity” (ATL, 2011, T.d.A p. 306).

The two Plans proposed to improve the quality of urban space through the requalification and redevelopment of specific areas of the city. This proposal was in line with the actions planned by the Lisbon City Council, in particular with the 2010 Baixa‑Chiado Rehabilitation Project (ATL, 2006) and the requalification of the riverfront areas. The two Plans identified the improvement of infrastructure as essential to increase tourism. The plans highlighted the need to capture low-cost airlines, taking advantage of the expansion of the Humberto Delgado Airport in 2007, and to build a new cruise pier (opened in 2017).

In terms of taxation, TLx14 included the proposal to create a new tourist tax to be allocated to a fund for tourism promotion. The municipal tourist tax was implemented in 2016 (Notice No. 10263/2015) at €2 per night. The ensuing revenues were managed by the Tourism Development Fund, run by a committee composed of the Lisbon City Council, ATL and business associations in the sector, and used for projects or activities with an impact on tourism development (Deliberation No. 3/CM/2016).

The TLx10 and TLx14 were, therefore, aligned with the Lisbon City Council’s spatial planning strategies. This can also be seen in the Lisbon Urban Rehabilitation Strategy 2011-2024, which provided for the “Urban Regeneration - Ribeira das Naus” program (Council of Ministers Resolution No. 78/2008) and the “Mouraria Action Program” (Ordinance No. 81/P/2011), of which ATL is a partner. The two operations were part of a broad set of redevelopment actions in the city's historic areas, with the ultimate goal of increasing the city's competitiveness. However, these actions contributed to the touristification of these areas and the eviction of the resident population (Ferreira, 2017; Tulumello & Allegretti, 2020).

Still in terms of spatial planning, a new Master Plan was approved in 2012 (Lisbon City Council, 2012). Among the structuring areas of the Master Plan in terms of tourism development, the following stand out: the requalification of the riverfront; the revitalization of the downtown area (Baixa Pombalina), which included increasing the hotel offer, improving commerce and restaurants, the development of an open-air shopping center concept, and creating a pedestrian zone. The Master Plan envisaged the change from housing use to other uses, particularly tourism, thus facilitating the doubling of hotels in the last decade (Figure 6).

In the early 21st century, Lisbon’s downtown was an area of widespread degradation and socioeconomic deprivation. An urban-commercial revitalization program was implemented in this area, as envisaged in the Master Plan (Menezes, 2017). However, direct observation shows that several buildings were subject to renovation and facade works, revealing the lack of integrated urban rehabilitation plans to safeguard heritage.

At the end of the TLx14, the 2015-2019 Strategic Tourism Plan for the Lisbon Region (ERT-RL, 2014) was drawn up, focused on improving products and services that would raise standards in the city and the region to higher levels. In Lisbon, strategic programs were defined for the areas of greatest tourist interest. The aim was to attract new cruise segments through the new Maritime Station and to develop and promote Lisbon internationally as a reference destination for MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions). In 2018, Lisbon became the 6th city in the world in terms of number of congresses, hence, the 2020-2024 Strategic Tourism Plan for the Lisbon Region (ERT-RL, 2019) envisages the construction of large conference venues to continue conquering this market.

According to the 2020-2024 Plan, tourism in the region has achieved excellent performance in recent years. The mission for the future is to “ensure the sustainability of the destination (…) and prepare a new growth cycle” (ibidem, (T.d.A.) p. 151). This depends on improvements to the Lisbon airport and a new airport in the neighbouring municipality of Montijo.

There is a concern with sustainability in the 2020-2024 Plan, seen primarily as the need to limit the city’s growth rate. It highlights a number of negative impacts from tourism and mitigating measures to promote quality for both the tourists and local residents. The high number of STRs in the center of Lisbon is a major concern.

In the last decade, the STRs have become predominant in Lisbon, contributing to a crisis in the housing sector (Mendes, 2017). The initially low housing prices attracted the interest of the global market. Following market liberalization and the successive rises in prices, high profits were easily obtained (Malet Calvo et al., 2018). Between 2016 and 2021, the average selling price of housing increased by 75.8%, from €1875/m2 to €3296/m2 (INE, s.d.). Due to growing tourism and the national policies described above, the number of STRs announced on online platforms increased exponentially, reaching 19.313 units in 2021 (TdP, s.d.). This situation has contributed to the eviction of the local population (Cocola-Gant & Gago, 2019).

For these reasons, STR Municipal Regulations (Regulamento Municipal do Alojamento Local) (Notice no. 17706-D/20199) were passed in 2019, which define a ratio between the STR and the properties available for housing. Areas have been delineated in which new licenses cannot be granted, except under exceptional circumstances. In the rest of the city, new licenses are issued without restrictions.

These regulations constitute a starting point in the search for a balance between the residential and tourist uses of housing. However, it has several flaws, namely: i) it is based on outdated quantitative data (2011 Census); ii) it does not provide for periodic monitoring of STR growth, nor does it anticipate the possibility of excessive growth in other areas, specially those bordering the containment areas; iii) it does not foresee reducing the number of STRs in already saturated areas; iii) it permits licenses in containment areas, in exceptional cases.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a sudden drop in tourist activity (Figure 2). Thanks to the flexibility of the model, STR owners migrated to medium-term rentals (Cocola-Gant, 2020). This is one of the reasons why the Renda Segura Program (Deliberation No. 68/CM/2020), in which the municipality intended to rent houses to STR owners, vacant properties or free buildings, and sublet them at affordable prices, has not been successful thus far. This is probably due to the expectation of tourism recovery, and to the reduced attractiveness of the program for landowners (Pavel & Romeiro, 2022).

The pandemic has exacerbated socio-spatial inequalities, residential segregation and territorial exclusion, operated through the triad of touristification, real estate speculation, and housing financialization (Mendes, 2021). After 2008, Lisbon witnessed an increase in civil society protests and urban social movements in favor of the right to housing and to the city, with emphasis on the work of the Habita Association, Morar em Lisboa Movement (MeL), and the Stop Despejos Collective (Mendes, 2021; Malet Calvo et al., 2018; Estevens et al., 2022). These social movements work to raise awareness in civil society and public opinion, as well as in international networks (e.g., MeL is part of the SET Network - South Europe Cities Facing Touristification). They seek dialogue with government authorities, demanding also legislative changes, such as amendments to the New Urban Lease Law or tourism degrowth policies.

5.2. Tourism in public policies in Porto

The importance of tourism in Porto is not recent, but it gained particular relevance in the public policy sphere at the end of the 20th century. Public strategies intensified in the 2010s, with a visible change in discourse and strategies during this period.

The positioning of Porto as a tourist destination is based on the recognition of its historic centre as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1996. This distinction established Porto as a cultural center, resulting in international prominence and a range of interventions to preserve and regenerate its built cultural heritage.

In 2001, the city was elected European Capital of Culture, which increased its international visibility. When applying for this event, Porto assumed its doubly peripheral position on the national and European scales (Porto Vivo - SRU, 1998), and targeted the socio-economic development of the city, particularly through cultural tourism (Porto Vivo, SRU, 1998). The “Porto 2001” project comprised an integrated strategy of extensive urban rehabilitation and regeneration and the creation or conversion of cultural spaces (e.g., Casa da Música, Almeida Garrett Municipal Library, Carlos Alberto Theater), as well as a new cultural landscape to attract investments and retain new residents.

There were expectations about the growth of tourism, and the Baixa and Historic Centre were identified as exceptional territories for this purpose. At this time, the potential of low-cost airlines to raise tourist demand was also addressed, as well as the relevance of other tourist segments (i.e., MICE) (Porto Vivo - SRU, 1998).

The Porto Downtown Urban Regeneration Strategic Plan for Urban Rehabilitation of the Porto downtown was developed in 2004 and 2005. The Master Plan for the Porto Historic Centre identified tourism as one of the pillars of social and economic rehabilitation (Porto Vivo - SRU, 2005), establishing a clear link between the significant increase in visitors and the city's economic revival. The plan recommended investments in new tourism activities in innovative areas. Among the main lines of intervention, the following stand out: i) increase the offer of 3-star hotels, through the rehabilitation of buildings and/or improvement of existing guesthouses, bed and breakfasts, and inns; ii) create a network of Boutique Hotels; iii) implement urban tourist itineraries (Porto Vivo - SRU, 2005).

In line with the strategic plan above, the Management Plan for the Porto World Heritage Historic Centre was presented jointly by the Porto City Council and Porto Vivo, SRU - Sociedade de Reabilitação Urbana da Baixa Portuense, S.A., in 2008. It presented an exhaustive analysis of real estate with cultural and architectural interest, a list of potentialities and threats to their state of conservation, as well as an Action Plan aimed at solving the problems identified, based on a long-term management model. This Management Plan for the Porto Historic Centre included tourism, mentioning measures from the National Strategic Tourism Plan, as well as the importance of establishing Porto as a City Break destination, as a tool to develop and retain other tourist products/services for emerging segments (e.g., family, seniors, gastronomy, wine tourism) (Porto Vivo - SRU, 2005).

On another plane, in the early 2000s, the Francisco Sá Carneiro Airport assumed crucial importance in the tourism development of Porto. After expansion and improvement works (2007), Ryanair announced the opening of its base in July 2009, becoming the first foreign company to be established at the airport. In the following years, other low-cost companies would come to operate at this airport (e.g., EasyJet, Transavia).

In terms of tourist-related infrastructure, the national and regional strategies in the area of transport are particularly relevant. Extensive works were conducted at the Francisco Sá Carneiro Airport and a development plan was also designed to increase its capacity. The opening of a new cruise ship terminal in Leixões followed later (2015), with significant impact on the city's tourism, co-funded by the 2007-2013 Northern Regional Operational Program (ON.2 - Novo Norte) (CCDR-N, 2008). This crucial project for Porto and the North Region involved the Douro and Leixões Port Administrations and a range of other agents. This project adopted an integrated perspective that linked three priority areas for the North region: the sea (namely its passenger, leisure, and tourism dimensions), tourism (through cruise tourism), and cities (tourist and maritime cities) (CCDR-N, 2011).

In terms of coordination, the Porto Municipal Tourism Council was created by deliberation of the City Council at the end of 2019. This advisory body promotes the regular involvement of a wide range of agents from the public, private and associative sectors, representing various areas directly and indirectly related to tourism, including eight representatives from municipal departments (Porto City Council, 2019). As such, this forum should also serve as a platform for political cooperation in a such transversal sector as tourism. However, the absence of representatives from civil society in this coordination network is one of its shortcomings.

Regarding measures of a fiscal nature, the City Council established a tourist tax in March 2018 (Ordinance No. 63/2018). The tax is considered to be a contribution to the sustainability of the city's tourist offer, particularly the wear and tear resulting from the tourist footprint. This rate applies to overnight stays paid in tourist or STR establishments, applied per night for up to a maximum of seven consecutive nights per person, regardless of the type of booking (Regulation No. 63/2018). This regulation was revised two years after its entry into force, in order to accommodate legislative changes and “better define some rules regarding aspects such as supervision and administrative offences” (Ordinance No. 63/2018).

In July 2019, the Porto City Council drafted new STR regulations, which proposed a ratio to delimit restricted tourist areas in the Porto Historic Centre and Bonfim area, as well as stricter requirements in the registration phase, the creation of the figure of STR mediator, and a code of conduct and good practices. These proposals were based on a study developed by the Catholic University of Porto, commissioned by the City Council, which analyzed updated STR data taken from the National Local Accommodation Register and the number of new water supply contracts in this type of accommodation. However, the proposal for the STR Regulations was revoked in April 2020, due to the pandemic crisis and uncertainty in the tourism sector.

Porto is suffering from the impact of the rapid, intense growth in the tourism sector. The magnitude of this impact in terms of demand can be seen in the numbers achieved in 2019: more than three million guests (Figure 2), over 13 million passengers through the Porto airport (Figure 5), and more than 88 thousand through the Leixões port (APDL, 2019). The supply has also followed this trend, having reached 99 Hotels (Figure 6) and 8573 STR registrations in 2019 (Figure 4).

The municipality’s economic and housing policies have been criticized in recent decades, particularly because the “redevelopment permits were not negotiated to secure the provision of affordable rental housing in situ, the creation of mixed communities, and to regulate the use of dwellings for non-permanent accommodation” (Alves & Branco 2018, p. 475). Over the last few years, several citizens and civic movements have raised concerns regarding the preservation of the city’s heritage, as well as the defense of affordable housing and prevention of evictions. Particularly noteworthy is the The Worst Tours association, which promotes walking tours, encouraging debate and urban activism, or the “O Porto não se Vende” movement, which claims the constitutional right to affordable housing for all. In 2019, ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) published a report on “World Heritage at Risk”, which mentioned the threats that loom over the Porto Historic Centre as a World Heritage Site (i.e., loss of historical authenticity or cultural significance, primarily due to reprehensible renovations of buildings). The article went as far as to say the city risked losing its UNESCO listing. However, these protests and calls to attention do not seem to have had any relevant impact or consequence in terms of municipal policies, due most likely to the lack of robust collective action.

In terms of spatial planning, the municipality's tourism vision and strategy has yet to be included in any of its development plans. The current Municipal Master Plan (July 2021) introduced the need to lower tourism concentration, whose impact is particularly severe in the Porto Historic Centre. Emphasis has been placed on the city’s eastern area, stressing the need for the Campanhã Multimodal Platform (transport infrastructure), the reconversion of the Municipal Slaughterhouse (business and cultural infrastructure), and the requalification of the Frente Ribeirinha - Freixo with an expected positive impact in the area of cultural tourism.

Cross-reading of municipal public policies in tourism

Tourism policies at the municipal level in Lisbon and Porto have followed the evolution of policy at the national level, as well as the evolution of urban dynamics at the local level. Changes in tourism public policy have led to a greater regionalization of competences in terms of strategic planning and financial management. Amendments to legislation regarding tourism have led municipalities to develop local policies aimed at correcting some of the negative impacts of tourist pressure in cities, mainly in terms of housing policy. However, they have not been sufficient to mitigate existing asymmetries in the housing market (Tulumello, 2019). Local authorities are not explicitly in charge of tourism, even though city councils are involved in a number of strategic areas in tourism development, such as planning, coordination, infrastructure, regulation, and information, among others.

In terms of tourism planning, neither the Lisbon nor the Porto City Councils have so far drawn up mid-/long-term strategic plans for tourism development. In both cases, the Master Plan is the main tool of their planning process. The strategy for tourism development in Lisbon is more explicit and has been articulated with other spatial planning tools, mentioning clearly urban development for tourism purposes. In both cities, spatial development tools at the municipal level intersect with the guidelines defined in the regional development plans for the area of tourism.

The two municipalities have invested in tourist-related infrastructure and equipment, particularly in the area of transport and culture. In terms of urban mobility, regardless of the role municipalities play in this sphere, the rise in demand generated by tourism has overloaded the public transport network, affecting the quality of life of residents and workers in these two cities.

Regarding regulation, both cities created a municipal tourist tax, intended to mitigate the effects caused by tourism. However, there is no clear link between the revenue generated and investment in actions to relieve tourist pressure on urban space. For example, the tax in Lisbon is mainly used in projects or activities related to tourism development, as it is the case of museums (e.g., Palácio da Ajuda, the Jewish Museum) or events, such as the Eurovision festival in 2018 (Deliberation No. 364/AML/2019).

Still with regard to regulation, both municipalities have acknowledged the need to create regulations for tourist apartments. In the case of Porto, the COVID-19 pandemic led to the repeal of the regulations in force. In Lisbon, the regulations introduced in 2019 were a first approach to safeguarding the residential use of housing, despite having several flaws.

As for the bodies dedicated to coordinating tourism activities, the Porto Municipality created a governance structure, the Municipal Tourism Council, to foster the regular involvement of a wide range of agents from the public, private and associative spheres, in promoting tourist offer and the city as a tourist destination. However, this body does not include representatives from the local community and its action and real contribution to the development of tourist activity are not visible or communicated to society.

Although both cities have specific strategies and tools related to tourism development and management, their alignment with public policy is visible. In Lisbon and Porto, tourist development has been instrumental to economic growth, more intensely after the 2008 financial crisis. The rapid, exponential growth of tourism has raised relevant urban challenges, namely in terms of pressure on property prices, both for residential and commercial purposes. The most recent policy guidelines raise concerns regarding the sustainability of tourism activity. However, this is mainly seen from the perspective of decentralization and the expansion of tourist-related areas, seeking to foster continuous growth while slowing its impact on the more central areas of the two cities.

Despite the negative impacts of tourism on the daily lives of the residents, both municipalities have not implemented forms of civic participation, thus preventing citizens from playing an active role in policy making. In recent years, protests and urban social movements have spread against rising socio-spatial inequalities and the neoliberal growth model adopted by the two municipalities. In Lisbon, urban social movements have played a particularly active role, with strong media impact, and have engaged with public institutions. In the case of Porto, there have been some urban social movements that demand the right to the city and housing, but they are fragmented and have been unable to reach the relevant institutions.

Conclusions

This article has addressed the challenges of urban development caused by the intense, rapid growth of tourist activity in the cities of Lisbon and Porto, and explored the role of local public policies. In Portugal, as in other European countries, competences in the field of tourism are mainly concentrated at the national and regional scales, which is why a multi-scale analysis is particularly relevant.

The analysis of tourism policies at the local scale is complex due to a combination of factors. Municipalities do not have direct authority in tourism development (except for tourism licensing), even though the dynamics and impacts of tourism are felt mainly at the local scale, and encompass directly and indirectly a diverse range of activities and stakeholders.

Portugal’s two main cities are facing major political challenges, given that many problems caused by the rapid, exponential growth of tourism that have not been effectively addressed. Further deterioration of the residents’ quality of life may be the inevitable consequence, marked by dysfunctions in the housing market, transport, public space and waste, among others.

Lisbon and Porto follow similar paths, despite experiencing different dynamics in terms of magnitude, intensity and impact. Tourism is seen as a key activity in urban development, particularly in terms of economic recovery after the 2008 financial crisis, affecting directly the hospitality sector and indirectly construction, commerce, culture, and leisure. In both cities, local policies in the area of rehabilitation and construction, favored in national policies, have led to the significant rise in residential and commercial property prices.

Both cities have achieved the growth goals defined for the sector in the regional (and national) tourism development plans, expressed in local policies to attract investment and territorial marketing strategies. However, despite measures to mitigate the negative impacts of the rapid, intense and geographically concentrated growth of tourism in the two cities (e.g., affordable housing policies), these have so far proved to be insufficient.

The expected rise in the global flow of tourists in the coming years and of residents in urban areas (UNWTO, 2014) will add millions of tourists to a growing urban population. Therefore, in order to fully embrace the present and future challenges of urban tourism, as well as the possible implications for cities, public policy must consider approaches that seriously integrate concepts such as sustainability, participation and innovation.

Recently, sustainability has been included in national and regional tourism development plans. However, this concept and related principles have not translated into consistent actions in local policies and strategies. At the same time, the quality of urban territories, particularly the environment and landscape, is often seen as a key element in tourism development, while spatial justice and heritage conservation (built and natural) fade into the background. At the same time, the great dependence of both Lisbon and Porto on tourist activity has become dramatically evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the political level, the strategy to decrease tourism as a path towards more sustainable tourism, advocated by urban social movements, has been disregarded.

Finally, there is a need to broaden the study on participatory approaches in the definition of tourism public policies, in order to respect the vocations and needs of the various stakeholders, as well as channel public resources towards more sustainable spatial development and tourist activity.