1. Introduction

In 1996, a group of literacy education theorists known as “The New London Group” (NLG) called for an urgent renewal in literacy pedagogy intended to provide an effective answer to the emerging “new learning needs” (New London Group, 1996, p. 61) of the then fast approaching 21st century. The NLG claimed that the emerging patterns of social diversity called for specific pedagogical approaches that might grant every student equitable access to education, regardless of their cultural and linguistic identity. Additionally, they contended that the changes brought about by digitalised communication required an expansion of the object of learning, thus placing multimodal meaning design as the object of new literacy pedagogy rather than verbal language alone.

Since then, the NLG’s manifesto for a “pedagogy of multiliteracies” has had an unprecedented impact on research and theorization in education (cf., Kulju et al., 2018; Lim et al., 2022). A particularly striking effect has been the increasing collaboration between close interfacing areas, such as education, semiotics, and media design, which are now challenged to combine in designing and producing innovative support materials - for example, up-to-date texts using the latest media - to promote the new pedagogy. This article is itself positioned at this crossroads since we are a research team of linguists, literacy researchers, digital media designers and producers working together to explore the design possibilities involved in this challenge.

In this article, we focus on a story app incorporating digital media that we have conceptualized, designed, and developed to support children’s intercultural, multimodal meaning-making by pre-school and primary school children. Mobeybou in Brazil provides a multimodal narrative set in Brazil, which aims to allow children to learn about the diversity within Brazilian culture and history as well as the country’s biodiversity, and to develop positive attitudes towards such diversity. This is especially important in the context of the current flow of Brazilian emigration, which is placing children of Brazilian origin in many different classroom situations around the world.

We have been studying this story app to further understand the multimodal design of intercultural meanings (Gil et al., in press; Pereira et al., 2022). Given the specific theme of this issue, we have now reviewed the app using the following research question: what can we learn about the design of multimodal texts aimed at promoting intercultural learning from the design of this story app? We begin by briefly presenting the theoretical framework supporting the study, situating, and describing the app. Before describing the study procedure, we pose two sub-questions that have guided our analysis, namely: (a) how is Brazil’s cultural and historical diversity, as well as its biodiversity, represented in the multimodal story app?; and (b) how is the reader positioned to construct positive attitudes towards such diversity in the multimodal story app?

We describe the multimodal discourse analysis that we performed to answer the main research question and the two sub-questions, employing categories taken from grammars of storytelling and multimodal meaning-making (Painter et al., 2012), in particular those associated with the representation of experiential diversity and the personal positioning of the app users, as we will detail below. The findings provide evidence of the complexity involved in the design of each set of meanings and the overall design of this multimodal text as a coherent whole, suggesting the importance of narrowing the interfaces within research developed in education, semiotics, and digital media design to meet the challenges of developing multiliteracies pedagogy. This is the main point of our article, which we discuss with reference to existing research. We conclude by identifying the limitations of our work and indicating some future developments.

2.Theoretical Framework

“Multiliteracies” were defined by NLG (New London Group, 1996) as the multiplicity of communicative practices characterized by new (or renewed) meanings and new (or renewed) communicative intentions, shaped in new (or renewed) textual formats and represented according to the new material possibilities (affordances) of meaning representation offered by digital media in the fast-growing information economy (Gee, 2007; Kalantzis & Cope, 2012; New London Group, 1996, 2000).

Multiliteracies pedagogy calls for a shift in pedagogical approaches to empower citizens with the knowledge and necessary skills to participate in contemporary communication environments fully (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009; Kalantzis & Cope, 2012; Mills, 2016; Mills et al., 2023), which are essentially characterized by multiplicities of media and modes, and by an “increasing local diversity and global connectedness” (New London Group, 1996, p. 62). In this context, the proposed multiliteracies pedagogy poses two major challenges to educational contexts, namely: (a) the need to create learning contexts in which students learn to make multimodal meanings; and (b) the need to make cultural diversity a mandatory object of learning (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009).

2.1. Multimodal Meaning in the Pedagogy of Multiliteracies

In multiliteracies pedagogy, the definition of this new knowledge and set of skills is openly supported by the theory of social semiotics (Kress, 2010), which assumes that human communication is essentially multimodal. According to social semiotics, the representation of meanings implies the use of modes, understood as “socially shaped and culturally given” (Kress, 2010, p. 79) semiotic resources. According to this understanding, material resources (modes) include not only written language but also oral language, together with other modes such as still and moving images, color, sound, music, and layout/space, all used intentionally to construct (encode and decode) representations to communicate meanings. Social semiotics further assumes that each mode has its own specific grammar, comprising units and rules for representing meanings (Kress, 2010). These grammars “have led to a stability and predictability in the construction of meaning” being “the product of the history of previous semiotic work of the members of a community” (Bezemer & Kress, 2016, p. 22).

Social semiotics, stemming from systemic functional linguistics, assumes that the grammar of any mode serves the representation of three types of meaning: experiential, interpersonal, and textual (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004) and that the way each type of meaning is realized is defined by the affordances of each different mode, that is, their material potentials and limitations for the construction of meaning, thus leading to the realization of grammars that are distinguished according to these modes (Bezemer & Kress, 2016). This explains why different modes represent different meanings, why meanings represented in one mode always differ from those represented in other modes, and why it is important to understand and learn how to use all modes. While this theoretical model of human communication did not emerge regarding digital communication, the multimodal affordances of digital technologies have turned multimodality into a prominent feature of digital meaning representation (Kress, 2010; Mills, 2016; Mills et al., 2023; Stein, 2008; Rowsell et al., 2013).

One of the most important repercussions of the centrality attributed to multimodality, both in communication at large and in digital communication in particular, is the revised notion of text (Pereira, 2019). Although one mode may be dominant in the material realization of a text, what most often occurs in texts made available in digital media is that they are multimodal ensembles, in which the signs constructed by each mode are integrated into each other, forming laminations of meanings (Bezemer & Kress, 2016; Kress, 2010). In such “multimodal ensembles”, modes do not duplicate or ornament each other; rather, each mode performs different functions, each making “distinct, specific, and potent contributions to the multimodal whole” (Kress, 2010, p. 23), according to its affordances and grammars, while often maintaining varied intermodal meaning relations (Unsworth, 2006). The resulting signs - the texts - are “more than the sum of their constituent parts” (Kress, 2010, p. 23), emerging as an orchestration of coherent meanings, where “orchestration names an emphasis on the aptness of selection, the mutual interdependence and the ‘semiotic harmony’ of such elements” (Kress, 2010, p. 157).

In this understanding of communication, any multimodal meaning representation (receptive or productive) is an intentional process of meaning design:

design in the sense of construction is something we do in the process of representing meanings, to ourselves in meaning-making processes, such as reading, listening, or seeing, or to the world in communicative processes, such as writing, speaking, or making photos. (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, p. 175)

Accordingly, the design process is identified with learning. In multiliteracies theory, it is assumed that any process of design can be understood as a process of transformative learning:

in the life of the meaning maker, this process of transformation is the essence of learning. The act of representing to oneself the world and the representations of others transforms the learner himself. The act of designing leaves the designer Redesigned. (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, p. 177)

According to social semiotics theory, text design offers a more powerful basis for learning, given the multiplicity of meanings potentially represented in semiotic ensembles (Bezemer & Kress, 2016). It is, therefore, also important to recognize the materiality of modes because of their repercussions on the conception of learning (Kress, 2010; Stein, 2008). Indeed, different modes have different physical materializations (sounds, marks, textures, shapes, gestures), and such materiality is related to the sensory possibilities of the human body (physical materializations can be seen, heard, touched, smelled, tasted). As Stein (2008) states:

the concept of multimodality is inseparable from that of bodies. Bodies produce multimodality through the way they are sensory constituted and how the senses act in the world and are the target of others’ actions. The senses are highly sophisticated in the information they provide us: they do not act in isolation in most cases and this fact “guarantees” the multimodality of our semiotic world. (p. 26)

In the pedagogy of multiliteracies, a detached consequence of multimodal meaning representation is the redefinition of the sociocultural theory of learning as a complex semiotic process insofar as the complex set of semiotic resources with which these meanings are designed (besides simply verbal language) constitutes the essential toolkit for meaning-making and learning in any area of knowledge. Kress (1997) is clear in this regard when he argues that “it is essential to insist on undoing the connection, existing in common sense, between cognition and language, according to which the former is assumed to be dependent on the latter, not being possible without it” (p. 43).

For these reasons, multiliteracies theory assumes that the multimodal resources of meaning representation, each with its own grammar, potentialities, and limitations, should determine the content of new essential literacy learning in schools. The goal is for learners to both extend and master the knowledge and skills that enable them to orchestrate appropriately the multimodal meanings of the texts they read and produce, including, most certainly, those mediated by a screen (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009).

2.2. Linguistic and Cultural Diversity in the Pedagogy of Multiliteracies

Another central argument of multiliteracies pedagogy is the need to extend the scope of literacy pedagogy to account for culturally and linguistically diverse contemporary societies. Indeed, cultural and linguistic diversity is a major factor in 21st-century societies due to migration, so learning to sustain and promote human rights and social justice has become another key priority in schools. The NLG’s viewpoint reflects the Council of Europe’s (2008) call to foster an intercultural pedagogical approach to cultural diversity, focusing on recognizing individual identities and linguistic and cultural plurality and establishing a dialogue based on equal dignity and shared values. In a special issue of Comunicação e Sociedade dedicated to analyzing and deconstructing contemporary discourses on minorities in the public sphere (Martins et al., 2020), different authors draw attention to the importance of intercultural communication and collaborative dialogue to promote mutual understanding and respect (Silva et al., 2019). However, to move beyond mere intercultural rhetoric and achieve mutual transformation, it is crucial to adopt a critical perspective in understanding interculturality by not simply recognizing and tolerating the “other” but actively listening and engaging in dialogue with each other (Brasil & Cabecinhas, 2019). This corresponds with the United Nations’ Agenda 2030, which pledges to foster “intercultural understanding, tolerance, mutual respect and an ethic of global citizenship and shared responsibility” (United Nations General Assembly, 2015, p. 10).

2.3. Story Apps in the Construction of the Pedagogy of Multiliteracies

Following this new approach to literacy education, there is a need to design pedagogical methodology that fosters intercultural dialogue, including strategies for learning and teaching intercultural competencies and multimodal meaning-making. In particular, it is necessary to design learning experiences taking advantage of digital resources, creating opportunities for students to explore and perform ideas and identities using a range of multimodal resources (Lim et al., 2021).

Story apps, which are now more common in educational contexts, illustrate the potential of digital texts to enact such function, as suggested by some studies of narrative apps carried out in recent years. For instance, Zhao and Unsworth (2016) present a social semiotic analysis of touch design in story apps, discussing how interactive areas, hotspots, can contribute to meaning-making. They differentiate between extra-text interactive and intra-text interactive hotspots. Extra-text interactive hotspots are visual representations of certain functionalities (e.g., a microphone indicates the audio record function), without creating any further meaning within the story (Zhao & Unsworth, 2016, p. 92). However, the authors argue that interaction with an intra-text interactive design is, on the contrary, an act of meaning-making within the narrative. Hagen and Mills (2022) explore how rhythm may function in literary apps based on the understanding that rhythm forms an important part of the reader’s meaning-making in using literary apps. After an extensive analysis of a literary app, the authors argue that “rhythm not only contributes to the multimodal cohesional aspects of literary apps but is also fundamental to meaning-potential” (Hagen & Mills, 2022, p. 19). This shows that the multimodal relationships between image, music, sound, and other interactive elements in the design of such apps differ from those of printed book formats and foster new and dynamic interactivity during the reading experience. Finally, Frederico (2021, p. 21) discusses digital reading in early childhood from empirical analysis of reading events involving children and their parents engaged with literary apps. Based on her analysis, the author argues that digital literary reading in early childhood is a practice with three key characteristics: embodied, affective, and agentive. Thus, her study shows that literary apps bring to light a new participatory and agentive reading paradigm for young readers.

While the above-mentioned studies discuss a particular dimension of story apps, our research adds to this body of knowledge by presenting a comprehensive and indepth analysis of multimodal meaning design in a story app. Although apparently not often acknowledged in the literature, digital media design plays a central role in producing new material resources (like story apps), offering multimodal and intercultural texts that promote the adoption of multiliteracies pedagogy. In this article, we present a study focusing on one such case: a story app that incorporates a set of digital media that we have conceptualized, designed, and developed to support children’s intercultural, multimodal meaning-making at school.

3. Mobeybou in Brazil: A Case in Point

The app Mobeybou in Brazil (Pereira et al., 2022) incorporates they Mobeybou materials, a toolkit for young children’s digital storytelling developed to promote the adoption of multiliteracies pedagogy in the initial stages of education. The kit consists of a digital manipulative that uses wooden blocks to manipulate digital content, and a StoryMaker, a fully digital version (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Both are authoring tools for digital storytelling (and writing), complemented with apps displaying interactive stories set in specific cultures. Mobeybou in Brazil present a geographical map locating the culture on a world map, a 360° environment that encourages children to move their device around to explore and visualize the full environment, a puzzle, and a small game involving cultural elements. It also includes an augmented reality page allowing children to print their own augmented reality markers and bring the protagonists to life, and an inbuilt glossary with keywords from the story as well as detailed information about the culture represented. The kit enables children to learn about cultural diversity playfully, mediating digital play with “narration by doing” (Sylla et al., 2022) the following activities: reading, assembling, recording, writing, and drawing intercultural stories. Reading with the apps demands certain interactions from the reader (e.g., dragging elements, clicking on objects, moving the device around, etc.) at key moments to trigger animations and reactions from the main characters.

. Íris Susana Pires Pereira, Maitê Gil & Cristina Maria Sylla

Figure 1. The digital manipulative displaying elements from the China set

Íris Susana Pires Pereira, Maitê Gil & Cristina Maria Sylla

Figure 2 The StoryMaker displays elements from the Brazil set

The specific app that we examine presents an animated story about Brazil for children’s meaning-making, aimed at allowing children to learn about diversity in Brazilian culture and history, as well as Brazil’s biodiversity, and to develop positive attitudes towards such diversity. It was conceived as a resource that could help Portuguese teachers to include the increasing number of migrant Brazilian children in the classroom and highlight their identities, as well as helping their classmates engage with them in intercultural dialogue.

Mobeybou in Brazil narrates a Brazilian child’s experience and personal reactions on an imaginative journey through her country while reading an illustrated book she finds among her toys. The app reader can follow a girl or a boy, choosing the protagonist before starting to read the story. Here, we follow the female character, called Iara.

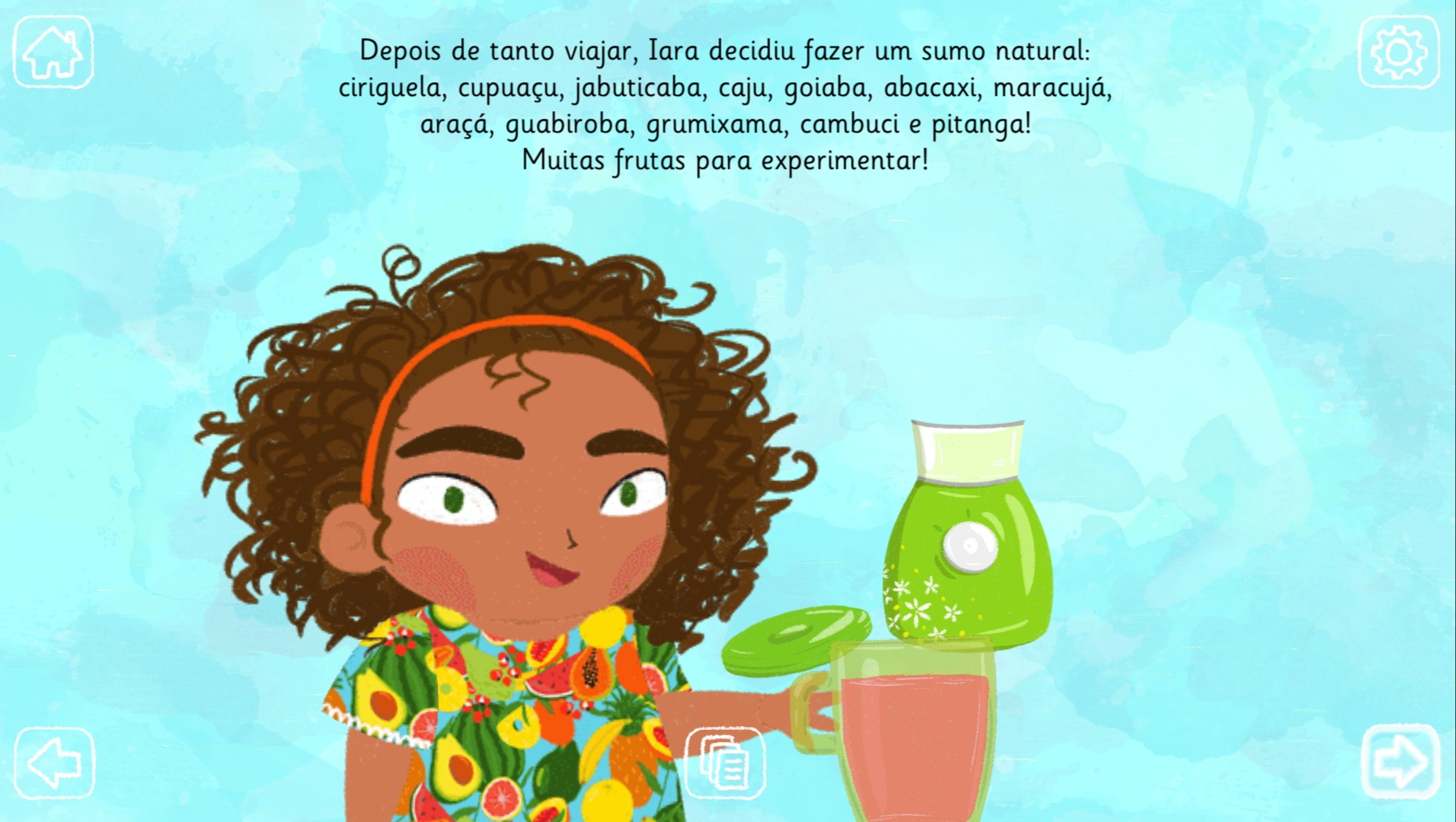

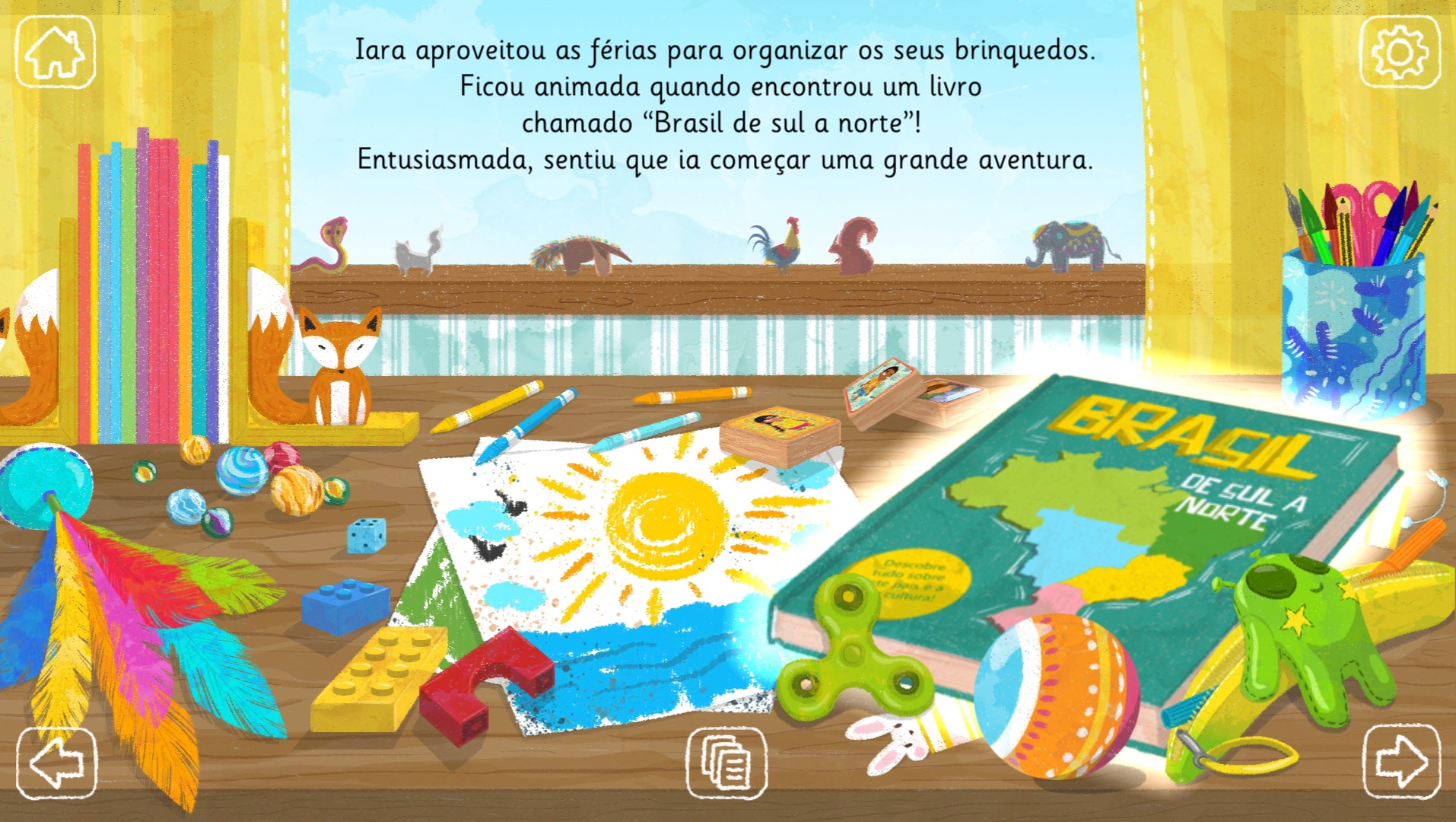

Being an “anecdote” (Martin & Rose, 2007), the narrative is structured into three phases - orientation, events, and coda - comprising a total of 11 episodes (see Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13). The first episode establishes the plot direction, introducing the triggering event: unexpectedly, Iara finds a picture book entitled Brazil From South to North among her toys and immediately imagines the start of an adventure. The next nine episodes consist of a sequence of events the character imagines as she progresses through the reading, during which she discovers Brazil and gets to know the different regions of Brazil: the pampas (Episode 2); the Iguaçu Falls (South region; Episode 3); São Paulo (Southeast region; Episode 4); the Pantanal (Centre-West region; Episode 5); Brazilian fruits (Episode 6); a beach in the Northeast region (Episode 7); the Amazon forest (north region; Episode 8); the popular Festival of Boi-bumbá (Episode 9); and the city of Recife (Northeast region; Episode 10). Finally, Episode 11 presents the coda, where we learn about Iara’s intention to travel and tell people about her learning. The narrative has two layers of narrative meaning: the first comprises the step-by-step reading of the book, culminating in the announcement of future journeys. This meaning is explicitly or implicitly present in the 11 episodes comprising the app. The second layer includes the imagined experiences of the protagonist during the step-by- step reading in a different Brazilian region/location.

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

Figure 3 Iara finds an illustrated book entitled Brasil de Sul a Norte (Brazil From South to North), among her toys (Episode 1)

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

Figure 5 Iara gets to know the Iguaçu Falls (South region; Episode 3)

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

Figure 6 360° representation of São Paulo (Southeast region; Episode 4)

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

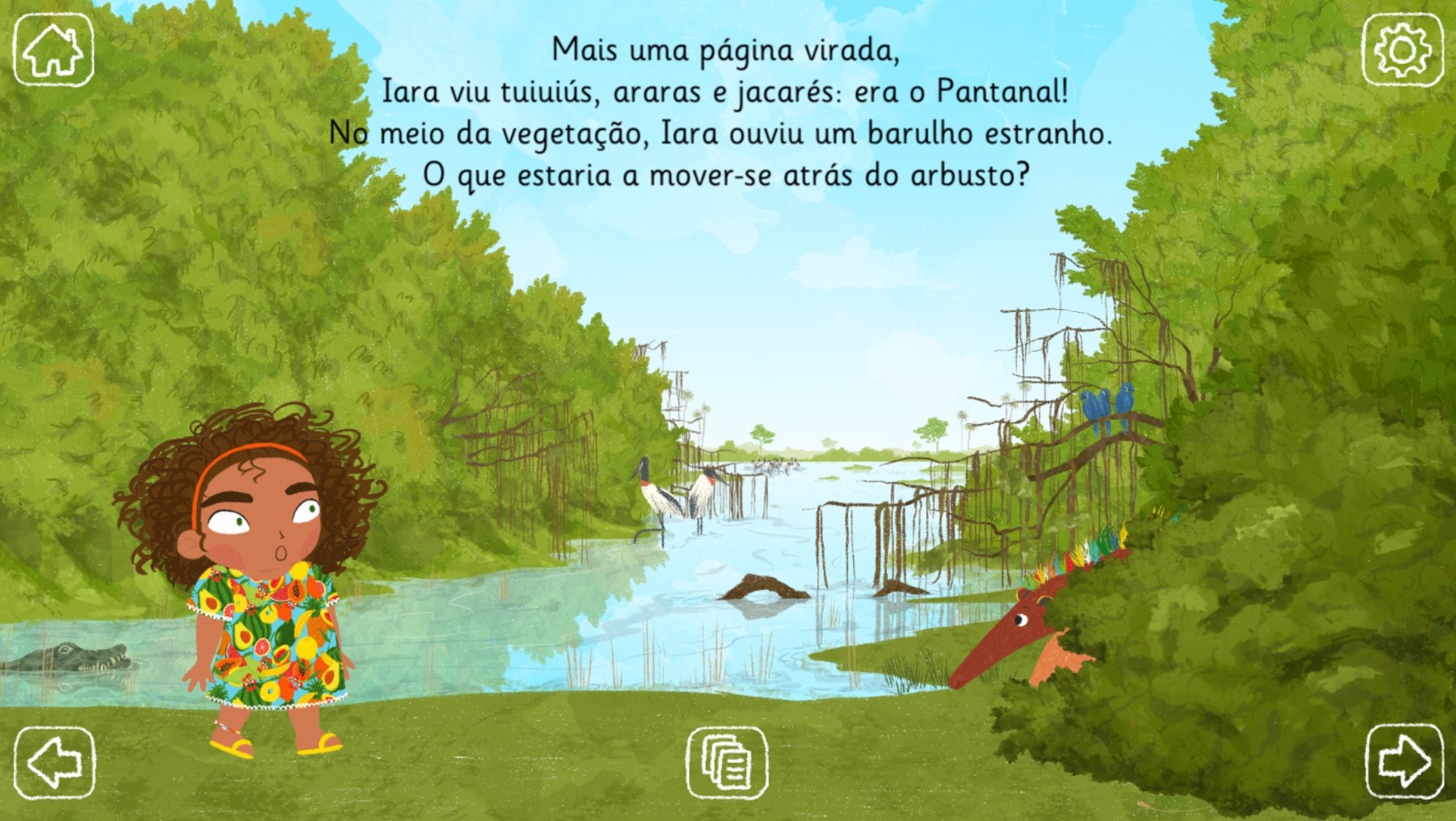

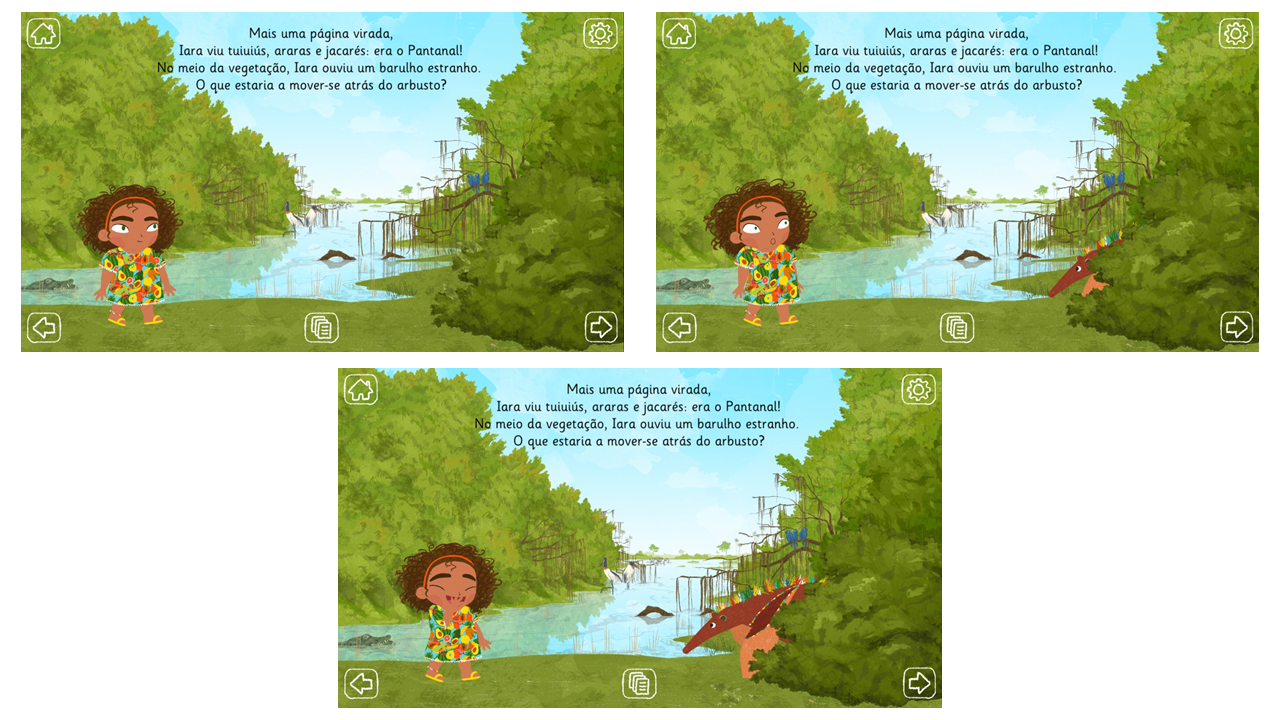

Figure 7 Iara visits the Pantanal (Midwest region; Episode 5)

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

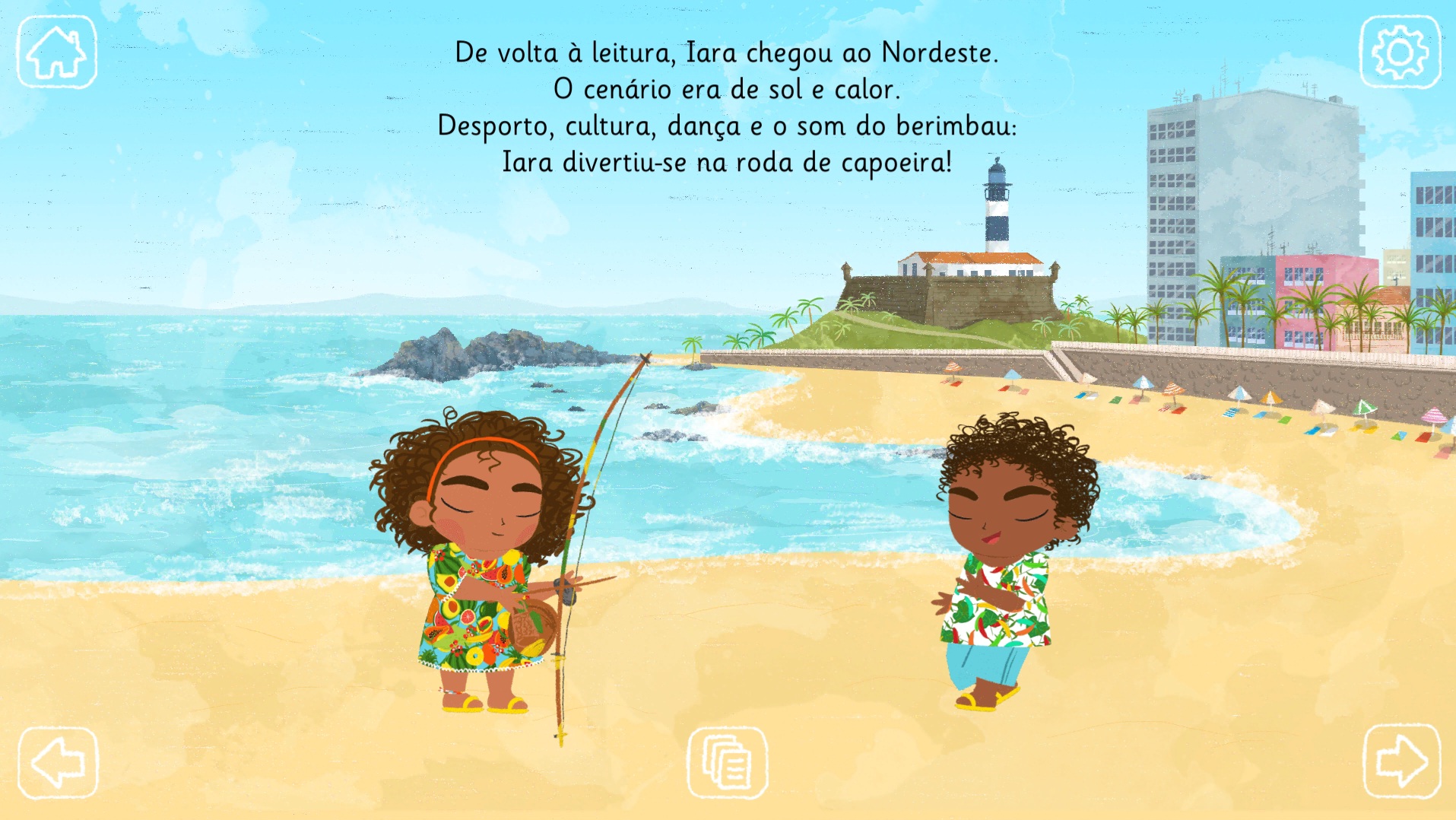

Figure 9 Iara visits a beach in the Northeast region (Episode 7)

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

Figure 10 Iara visits the Amazon Forest (North region; Episode 8)

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

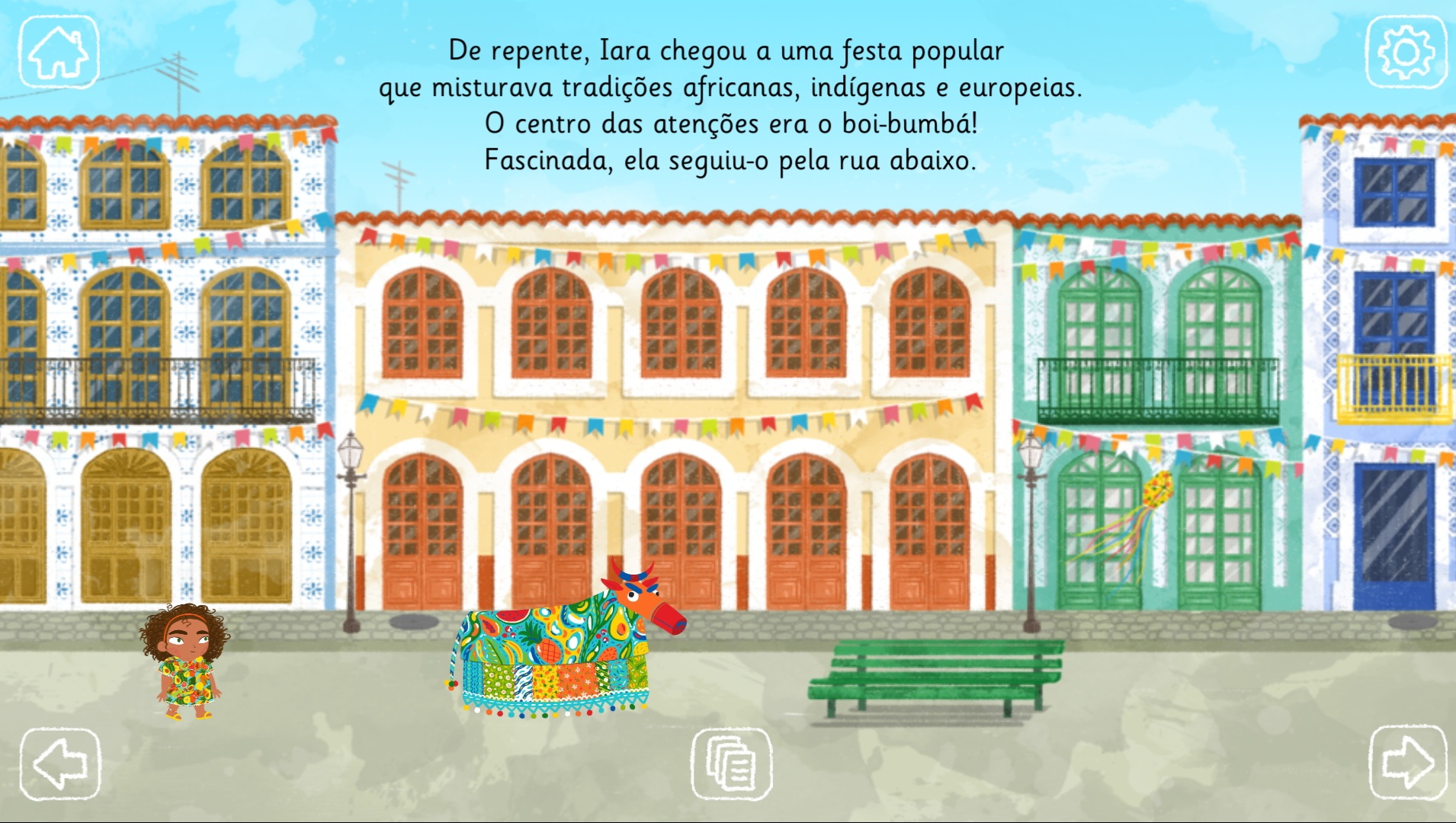

Figure 11 The popular celebration of the boi-bumbá (Episode 9)

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

Figure 12 The city of Recife (Northeast region; Episode 10)

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

Figure 13 Iara travels and tells her friends about her learning (Episode 11)

3.1. The Study

As outlined in the introduction, we have been analyzing Mobeybou in Brazil with the aim of understanding the multimodal design of intercultural meanings (Pereira et al., 2022). Given the specific theme of the present issue, we have examined the app using the following research question: What can we learn about the design of multimodal texts aimed at promoting intercultural learning from the design of this story app? By answering this question, we aim to add to understanding of the challenges posed in designing digital texts aimed at promoting multiliteracies pedagogy. To answer the question, we have divided it into two sub-questions focusing on the multimodal representation of meanings regarding “diversity” and the personal positioning of the reader towards such diversity:

How are cultural and historical diversity as well as biodiversity in Brazil represented in the multimodal story app?

How is the reader positioned to construct positive attitudes towards such diversity in the multimodal story app?

To answer these sub-questions, we performed a multimodal discourse analysis of Episodes 2 to 10 (the second layer of meaning in the narrative, which, as seen above, consists of the character’s discovery of diversity in Brazil). The analysis involved a blend of categories taken from systemic functional linguistics (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004; Martin & Rose, 2007), visual design (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006), visual narrative analysis (Painter et al., 2012), intermodal meaning relations (Unsworth, 2006), as well as some important contributions from narratology, particularly those referring to narrative focalization (Bal, 2017). These were useful in (a) identifying and distinguishing the meanings represented in the different modes; and (b) classifying the intermodal meaning relations established within their representation, as described below.

Meanings and Modes. Systemic functional linguistics helped us understand that the sets of meanings that we wanted to analyse consist of ideational meanings, that is, meanings about Brazil’s cultural and historical diversity and its biodiversity, and interpersonal meanings, specifically, evaluative meanings (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004), which is to say the reader’s personal positioning towards the ideational diversity that is represented. In Mobeybou in Brazil, the modes involved in representing these meanings are the verbal (oral and written), the visual (static and moving images), the aural, and gesture.

Ideational and Interpersonal. Meanings. We used “processes”, “participants”, and “circumstances” as key categories to identify ideational meanings (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004; Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006) represented in the four modes. Vectors, which are imaginary lines involving eye and body movements, were especially important to identify the visual representation of processes in which the character is involved throughout her imaginary journey.

We used “attitudes” and “sources of attitudes” as guiding categories to identify the representation of interpersonal meanings. Analysis of the representation of “attitudes” expressed in the verbal mode was guided by the categories of “affect” (the expression of feelings in verbal language) and “appreciation” (the appraisal of qualities and composition of the setting; Martin & Rose, 2007).

To analyse the design of the attitudes represented in the visual mode, we used categories derived from the grammar of visual narratives (Painter et al., 2012), namely “pathos” (in particular, facial expressions), “affect” (appreciative, empathetic, or personalized meanings inferred from depiction), “social distance” (ample, medium, or close-up frame), “involvement” (horizontal oblique, or frontal angle), “power” (lower, neutral or upper vertical angle) and “eye contact” with the reader/viewer. In analysing the attitudes towards the context/ambiance, we were guided by “variation”, “temperature”, and “saturation” of colors.

The meanings represented by these resources are important in personally positioning the viewer, for example, as being close to characters with whom the viewer personally aligns or distant from those with whom they do not align. However, the source of the attitudes represented also plays a role in constructing that positioning. We analyzed the sources of the attitudes represented according to the narrative focalization theory (Bal, 2017; O’Brien, 2014). In narratology, focalization captures whoever sees/experiences/feels and their evaluations (how they evaluate what they see/experience), contrary to whoever tells/ shows a story, the role always performed by the narrator. In our study, this distinction became especially significant because children to whom the story app is directed tend to align with the focalizer’s evaluations, receiving their attention and sympathy (Bal, 2017). We classified the focalizer according to the following categories: “external focalizer”, existing by omission and performed by the narrator (in the verbal mode) or the viewer (in the visual mode); “internal focalizer”, when it is the character who sees, in which case it is the character (and not the narrator) who feels, decides, sees, listens, observes, or experiences, and the reader/viewer is aligned with the character; and “double focalizer”, when the narrator can “see with the character” (Bal, 2017, p. 144), “as if peeking over his shoulder” (p. 146), in which case, the character themselves is responsible for the evaluation presented.

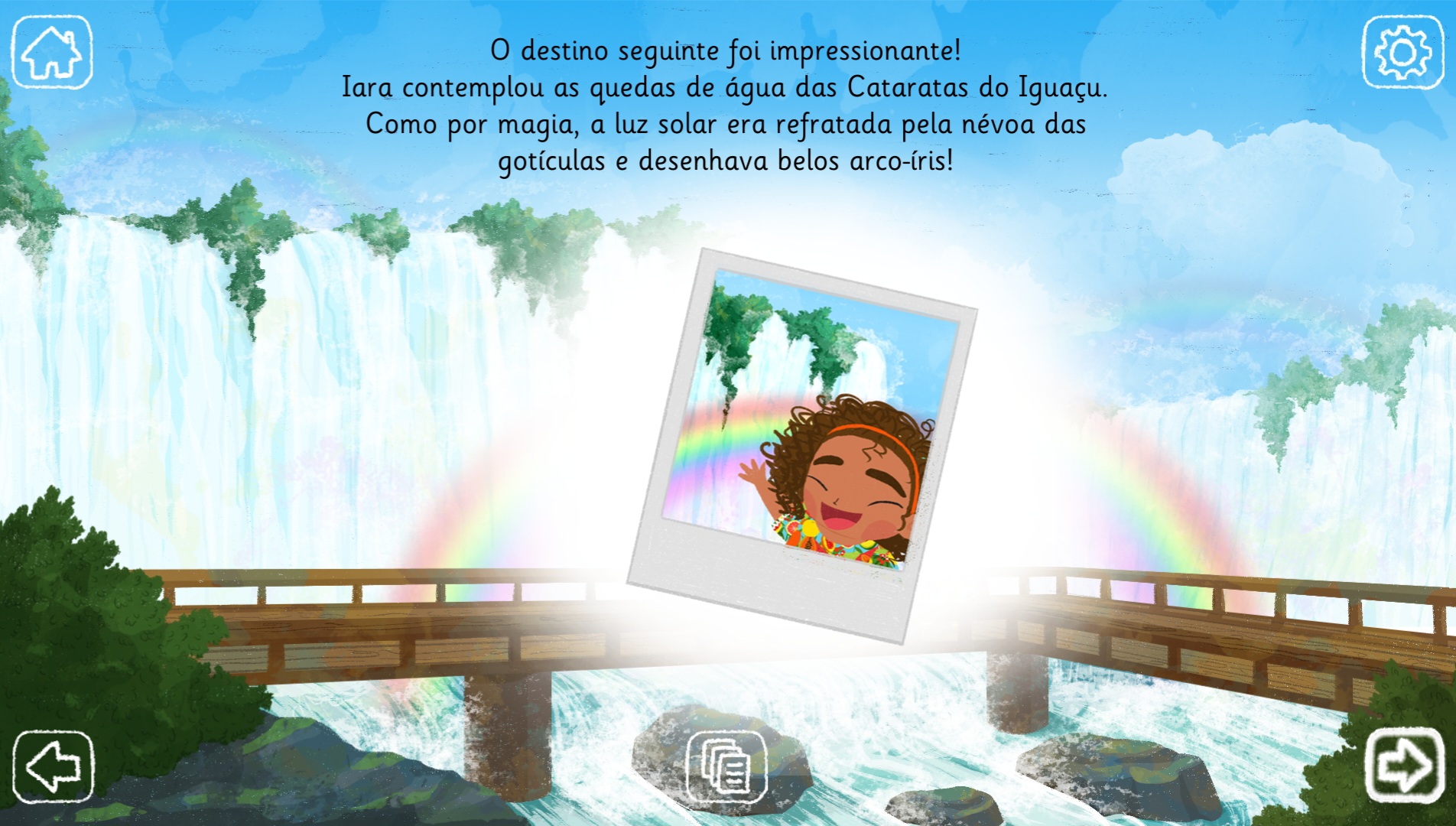

Intermodal Meaning Relations. To appreciate the multimodal representation of meanings, we applied a typology of intermodal meaning relations derived from Unsworth (2006) and Painter et al. (2012). We used three main categories: “convergence”, “complementarity”, and “connection”. “Convergence” designates the cases in which two or more modes represent equivalent or related information. We used two subtypes of convergence: “exposition” (when the represented meanings in the modes have the same level of generality) and “instantiation” (when a mode indicates an instance/example of an element represented by another). “Complementarity” consists of relations in which each mode contributes to constructing global coherence with different meanings. In the analysis, two types of convergence emerged: “resonance” (in the representation of attitudes) and alignment (in the representation of sources of attitudes/focalization). “Connection” consists of relations in which the information presented by one mode is related either by “projection” (when the information offered in one mode is projected by the information in the other) or “conjunction” (when that information has causal, temporal, or spatial meaning).

Finally, we quantified the intermodal instances in each analytical category to obtain a finer view of the multimodal nature of the text.

The analysis was performed by two authors independently. The preliminary results were discussed by all authors. Our final analytical tool is presented below (Table 1).

4. Findings

Our findings are summarized in Table 2. They provided rich evidence that this app uses intermodal construction of ideational and interpersonal meanings, as asked in both sub-questions leading the analysis.

The most significant representation on Mobeybou in Brazil is that of intermodal ideational meanings, with a consequent high density in the “information” presented about Brazil. The representation of intermodal interpersonal meanings is relatively less significant. We have also found that on this app, the role of the aural mode is always subsidiary in the intermodal construction of ideational and interpersonal meanings: it contributes with realistic sounds and music, which both converge and complement ideational and interpersonal meanings represented by the other modes. In some cases, the intermodal relation involves both the verbal and visual modes (e.g., when Southern lapwings, horses, and oxen, verbally referred, are illustrated - visual mode - and heard - aural mode - in Episode 2). In other instances, just one is present (e.g., when the visual mode - moving image - and the aural mode show the anteater in episode 5). For space reasons, we exemplify the resulting analysis of the intermodal design of ideational and interpersonal meanings in four episodes (Episodes 4, 5, 6, and 10).

4.1. Episode 4: Discovering and Appreciating Avenida Paulista

All four modes combine in the design of this episode, which follows a visit to the Iguaçu Falls presented in the previous episode. The verbal mode offers the following information: “from the lavish nature to a busy urban center. On Avenida Paulista, there were museums, buildings, cars, and noise. Both the beauty of nature and the commotion of the city are part of Brazil’s diversity”. The avenue and several elements are visually displayed, but not the character who sees the avenue. Gesture/touch is involved when the reader activates a 360° environment, providing the opportunity to simulate a “street view” by moving the digital device in all directions, as captured in the sequences of shots in Figure 14. Finally, the aural mode reproduces real sounds of large urban centers, including car horns, movement sounds, and people’s voices.

The four modes are closely intertwined in the construction of this episode, creating different intermodal relations in the representation of both ideational and interpersonal meanings.

Intermodal Ideational Meanings. A clear example of convergence by instantiation is found at the moment when the museums and buildings are generically mentioned in the verbal mode (“on Avenida Paulista, there were museums, buildings, cars, and noise”) and represented visually by concrete examples, such as São Paulo Museum of Art, a famous museum located in the Avenida Paulista. A clear example of complementarity by expansion is found when the images amplify the elements mentioned in the verbal text, for example, by representing buses and a park. Additionally, there is an instance of connection as causality since what the character sees and hears (visual and aural modes) leads her to an increased understanding of diversity in Brazil, as expressed in the verbal mode: “both the beauty of nature and the commotion of the city are part of Brazil’s diversity”.

Intermodal Interpersonal Meanings. An example of resonance between the modes can be found in the construction of a positive appreciation towards the avenue: the verbal mode contributes to “the busy urban center”; “the commotion of the city”; the visual mode shows color variation, generating a sense of familiarity, and dominant warm colors, creating a positive ambiance; and the sounds, in the aural mode, intensify the invitation for the reader to immerse themselves in the 360° environment.

An instance of alignment can be found in constructing the reader’s positioning through the focalization process. In this episode, there is a unique three-fold internal focalization, aligning the narrator, the character, and the viewer in the attitudes expressed: the viewer sees through the character’s eyes in the visual mode while listening to (or reading) the narrator’s voice, which clearly assumes the character’s appraisal expressed in the verbal mode. This three-fold focalization enhances the reader’s positioning towards the attitude of appraised diversity.

4.2. Episode 5: Being Surprised at the Pantanal Wetlands

After discovering the Avenida Paulista, the reader is introduced to the Pantanal. The verbal text is as follows: “another page turned. Iara saw jabirus, macaws and alligators: She was in the Pantanal! Suddenly, Iara heard a strange noise. Was something moving behind the bush?”. In the visual mode, the Pantanal wetlands are displayed. The protagonist is represented in the foreground next to (and looking at) a bush in the still image; in the moving image, another participant is presented: the anteater; Gesture/touch is involved in the reader’s activation of the moving image by clicking on the bush, and revealing the anteater, as captured in the sequences of shots in Figure 15. Lastly, the aural mode presents sound linked to concrete reality: the sound of the anteater moving, the sound of the bush leaves, the character’s laughter, moving water, and birdsong.

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

Figure 15 Sequences of shots in Episode 5, culminating in the discovery of the anteater

In this episode, the four modes also combine to construct ideational and interpersonal meanings through different intermodal relations.

Intermodal Ideational Meanings. In this episode, ideational meanings about the participants and their circumstances are constructed through a series of convergence relations between the modes. A perfect example of convergence by exposition relation is the verbal reference to the movement behind the bush (“suddenly, Iara heard a strange noise. Was something moving behind the bush?”), the movement of the leaves being visually represented, and its sound heard in the aural mode. The same instance illustrates an intermodal relation of complementarity as the visual mode shows the character looking attentively at the bush, as revealed by the vectors in her eyes. An instance of complementarity in intermodal meaning is the representation of the Pantanal’s wetlands, in which the visual mode amplifies the information presented in the verbal and aural modes, most notably by representing the water, which is not mentioned verbally. There is also a very significant relation of connection by projection among modes, in which both touch and visual modes offer information answering the question posed in the verbal mode. The anteater is presented, adding to the representation of diversity.

Intermodal Interpersonal Meanings. Considering intermodal relations in the representation of interpersonal meanings, an instance of resonance among the modes can be found in the construction of the character’s attitude of appreciation: the verbal mode contributes with “Iara saw jabirus, macaws and alligators: She was in the Pantanal!”; and the visual mode shows her attentive facial expression while observing the scenery at the beginning of the episode. A clear example of complementary relation is the construction of the proximity of the character to the reader, in which the visual mode complements the verbal mode through the positioning of the character in the scene: although presented at a horizontal, oblique angle in a medium size frame, which positions the viewer/reader as an observer, the characters are centered and presented at a neutral angle, suggesting the readers’ proximity and identification with the characters. Additionally, the different facial expressions of both characters express their positive reactions, which enhances the reader/viewer’s empathy.

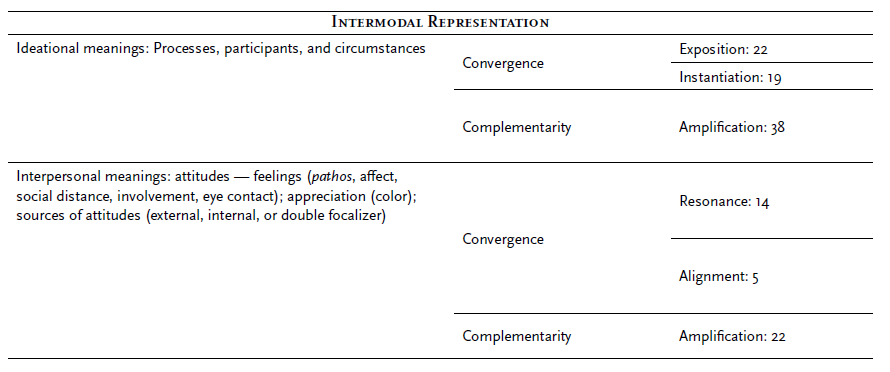

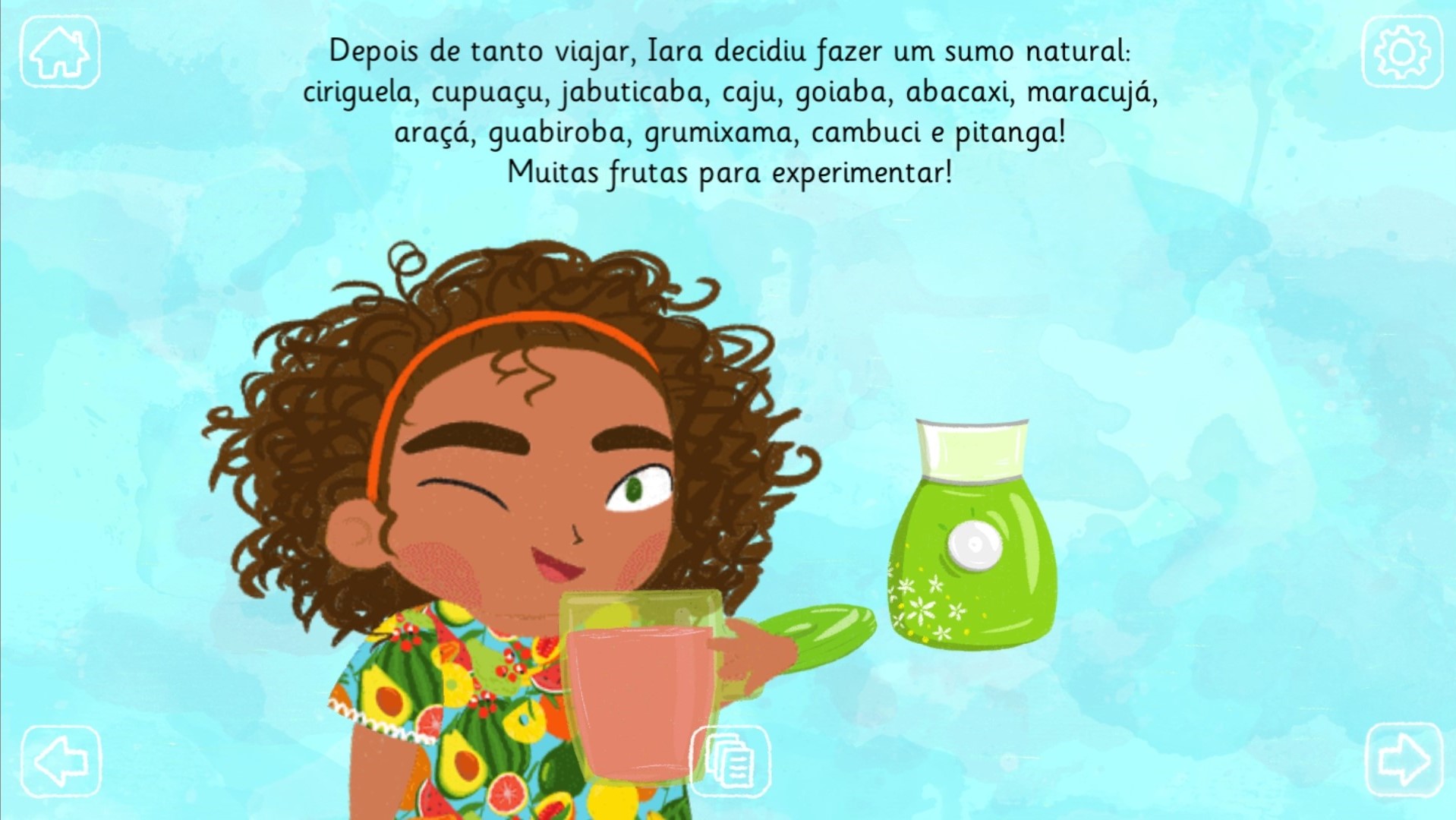

4.3. Episode 6: Tasting and Appreciating Diverse Brazilian Fruits

Episode 6 pauses the character’s imagined journey through her country and proposes the preparation of a natural juice with indigenous Brazilian fruits. The verbal text of this episode says: “after traveling to so many places, Iara decided to make a juice: siriguela, capuaçu, jaboticaba cashew, guava, pineapple, passion fruit, guabiroba, grumixama, cambuci, and pitanga! So many fruits to taste!”. A set of fruits is visually displayed with a blender, as in Figure 16. The viewer/reader is invited to drag each fruit into the bender using touch. When that action is finished, the character enters the screen and tastes the juice while at the same time turning to the reader/viewer and winking her eye, as captured in Figure 17 and Figure 18. The aural mode contributes to liquid sounds and the character’s humming and winking.

From Mobeybou in Brazil, by Mobeybou, 2020

Figure 18 When the juice is ready, Iara comes and takes it

Intermodal Ideational Meanings. In constructing ideational meanings, we find an example of convergence by instantiation between the verbal and visual modes when each fruit is visually displayed and verbally mentioned. An instance of complementarity is found in the visual display of the blender, which is not mentioned verbally (Figure 18). An example of connection by conjunction is found between the verbal mode and the moving visual image when the character tries the juice.

Intermodal Interpersonal Meanings. There is an instance of resonance among modes in the source of the appraisal of the fruits about to be used to make the juice, either in the verbal or visual modes: in both, the appraisal originates in the character. Another appraisal is made by the character, though only afterward in the moving image, when she looks directly at the reader/viewer and winks her eye to show her facial satisfaction, constructing an example of complementary intermodal relation (Figure 18). Together with her facial expressions, this eye contact is a powerful strategy to construct involvement and proximity with the viewer.

4.4. Episode 10: Knowing and Enjoying the Frevo

Three modes are involved in the design of Episode 10. The verbal text of this episode says: “holding a colorful umbrella, Iara felt the refreshing energy around her! She jumped and danced: The rhythm of Frevo completed the mosaic of Brazilian traditions”; visually (moving images), the character, holding an umbrella, is dancing in the foreground with two characters that she has previously met in her imaginative journey through Brazil: the anteater and the boi-bumbá (a character from a Brazilian festival), in a lively atmosphere (Figure 19); the aural mode contributes with the traditional sound of frevo. There is no intervention of the gestural mode.

Again, the different modes are intertwined in constructing this episode, evidencing several intermodal relations in representing ideational and interpersonal meanings.

Intermodal Ideational Meanings. Clear examples of convergence by instantiation are the mention of the frevo rhythm in the verbal text and its representation both by the aural mode and the moving image. An example of convergence by exposition is the reference to the colorful umbrella, dancing, and jumping in the verbal text and its display in the visual mode. Complementarity by expansion of meanings occurs, for instance, when the visual mode shows other characters dancing besides Iara, the only participant mentioned in the verbal text.

Intermodal Interpersonal Meanings. An example of resonance between the verbal and visual modes is the representation of the character’s attitude of affection: the verbal mode contributes by saying she “felt the energy that vibrated in the air”; the visual mode resonates by showing joyful facial and body language. Another case of intermodal resonance is in the representation of the character’s positive appreciation of the ambiance in the verbal mode and the selection of colors in the visual mode. By presenting the frevo rhythm, the aural mode actively contributes in this episode to immersing the reader/ viewer in the narrative universe, enhancing his/her experience of the intensity and joy of the musical rhythm.

A complementarity relation by amplification is found when the verbal mode complements the meanings presented by the visual with internal and double focalization: while the verbal text includes the point of view of the narrator (“holding a colorful umbrella”) as well as the character’s internal focalization and evaluations (“she felt the energy that vibrated in the air”), here assumed by the narrator, the scene is visually represented from an external focalization, with the three characters in a medium frame, presented in a frontal horizontal and neutral vertical angle, positioning the reader/viewer in a neutral power relationship with the character, definitively stimulating the reader/viewer’s affiliation with her.

5. Discussion

Having answered both sub-questions orienting the analysis, we can now present and discuss our answer to the research question leading the study: what can we learn about the design of multimodal texts aimed at promoting intercultural learning from the design of this story app? By answering this question, we aim to contribute to understanding the challenges posed by the design of digital texts aimed at promoting the adoption of multiliteracies pedagogy.

Our analysis has evidenced how the design of multimodal texts aimed at promoting intercultural learning involves the representation of two main sets of meanings: ideational and interpersonal, found in participants, processes, circumstances, attitudes, and sources of attitudes (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004; Martin & Rose, 2007). Additionally, our results have shown that different modes, in our case, the verbal, aural, visual, and gestural modes, contribute to different layers of meaning according to their affordances (Hagen & Mills, 2022; Kress, 2010). The verbal and visual modes contribute the most towards intermodal meaning construction, playing fundamental roles in representing culture, geography, and biodiversity and aligning the reader and viewer with the character’s very positive reactions towards such diversity. In addition, touch plays an important role in this app, enabling the reader to progress through the story and triggering animations and the main character’s reactions at key moments (Zhao & Unsworth, 2016). Throughout the text, touch and gesture are required to visually open new layers of significance (e.g., in Episode 1, by touching the book, a land map of Brazil is displayed; in Episode 4, by touching the bush, the anteater appears; or in Episode 6, by dragging Brazilian fruits into the blender to make a juice). Gestures and movement also allow the reader to visually “walk” the Avenida Paulista. Although the role of movement, gestures, and touch in meaning-making is often overlooked, and we tend to be more aware of and pay more attention to the role of the visual mode, this app evidences the existence of a close connection between manipulation, vision, and haptic feedback (Gibson, 1979). The role played by touch in the app seems to be aligned with Sheets-Johnstone’s (1999) claim about the centrality of movement in meaning-making, preceding perceptual-cognitive relations of ourselves and the world, and our linguistic capability. The aural mode plays a relevant role in the construction of this multimodal text as well, especially in physically immersing the reader/viewer in the diversity being portrayed and appraised.

Mobeybou in Brazil is, therefore, a multimodal ensemble in which meaning-making is necessarily a fully-fledged embodied process (Hagen & Mills, 2022; Mills, 2016). This aligns with Kress’s (1997) claim that:

all modes allow cognition, or cognition is possible, is realized, in all modes, although differently. This is the central point: written language enables one form of cognition; drawing, another; color, as a medium, still another; the production of physical objects and their interactive use, still others. (p. 43)

It also corresponds to the acknowledgment of the role of sensorimotor action in cognition across multiple disciplines and strands of thought, from evolutionary biology and neurology to phenomenology (Sheets-Johnstone, 1999, 2011; F. Wilson, 1998; M. Wilson, 2002).

Our analysis also shows that the various layers of modal meanings establish different meaning relations in the design of a text which is not presented as the sum of its parts, as a juxtaposition, or as a duplication of each layer of meanings, but rather as a coherent unity (Kress, 2010). Among the detached intermodal meaning relations that we have identified, convergence and complementarity are paramount in constructing this unity, as Unsworth (2006) described. It is these intermodal meaning relations that the reader/viewer finally needs to bring together in their mind to learn about cultural, historical, and biodiversity and develop positive attitudes.

The importance of our findings for the construction of the pedagogy of multiliteracies is two-fold. On the one hand, they illuminate key dimensions in the pedagogical work aimed at intentionally promoting intercultural learning in the classroom. Our findings not only offer teachers significant meanings to which they can guide students’ attention (therefore stimulating the development of students’ intercultural competencies) but also help them see, and therefore explicitly teach, how such meanings are being represented (thus stimulating students’ multimodal semiotic learning). Our exploratory studies, essentially involving pedagogical analysis of interventions conducted by ourselves, show that children enjoy reading this text, displaying embodied and affective as well as agentive meaning-making (Frederico, 2021). Moreover, our research reveals that they effectively learn and develop very positive feelings and appreciation towards Brazil, reflected in interpersonal relations with their peers. We now need to support teachers in learning about the workings of multimodal semiotic resources so that they can be empowered to undertake such interventions and teach students about semiotic resources to better scaffold their intercultural meaning-making.

Moreover, our findings provide evidence that design can indeed play an important role in producing significant multimodal texts to meet the challenges of building a pedagogy for multiliteracies. The analysis has shown the complexity lying behind the resulting app, evidencing how its design was underpinned by the convergence of research developed in education and semiotics, in particular by specific theoretical approaches to the multimodal construction of meaning with digital media design. Although ours is a case study, we dare to say that it points to the importance of narrowing the interfaces between such research fields when it comes to designing0 digital texts to promote the adoption of multiliteracies pedagogy. In our opinion, this is of potential significance, given the focus of this issue.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

In this article, we aimed to contribute to understanding the challenges posed by the design of digital texts aimed at promoting the adoption of multiliteracies pedagogy. We have focused our attention on a story app that presents a multimodal narrative situated in Brazil, aiming to give children the opportunity to learn about the diversity within Brazilian culture and history, as well as its biodiversity, and to develop positive attitudes towards such diversity. Our study provides evidence of the central role of digital media design in creating multimodal and intercultural texts that promote the adoption of multiliteracies pedagogy. We acknowledge, however, that our conclusions are limited by the nature of our inquiry, focusing on the case study of a story app and not allowing for generalizations.

In the future, we plan to extend the digital and tangible materials kit and continue designing interactive story apps targeting different cultures. Further, we will continue our work with teachers to investigate the potential and challenges of using such materials for adopting multiliteracies pedagogy.

texto em

texto em