1. Introduction

At the end of 2019, the world got to know the new coronavirus - SARS-COV-2 (Ministério da Saúde, 2020), the responsible agent of Covid-19. The name began to be used in February 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO), the result of a combination of the word Covid (COrona VIrus DIsease) and the number “19”, which refers to the year of discovery of the first cases in China, and more specifically in the city of Wuhan (Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, 2020a).

Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) were essential for countries to become aware of possible health measures to prevent the spread of the virus in other locations on the planet, such as those indicated by the WHO, worldwide, and by several reference institutions in Brazil, such as Fiocruz (Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, 2020b). Some of these measures were: maintaining social distance; use hand sanitizer with alcohol in its composition, or wash your hands frequently; cover your mouth and nose when sneezing or coughing; besides avoiding the sharing of personal objects, such as cutlery and glasses.

The sharing of experiences lived by countries that suffered from the new coronavirus at the beginning of the year 2020 helped to prevent the increase in the number of deaths due to Covid-19. However, ICTs have also been used to spread misinformation, fake news1 and may, to some extent, have aggravated the disease in several countries around the world, as pointed out by the study developed by Galhardi, Freire, Minayo and Fagundes (2020) entitled "Fact or Fake? An analysis of disinformation regarding the Covid-19 pandemic in Brazil". On this way this article provides an overview of COVID19 in the country and raises the issue based on the discussion of journalism as an event and/or form of knowledge (Park, 2002, Meditsch 1997;), aggregator of the power of scheduling public opinion by media, disturbing the agenda built by governments (McCOMBS, 2009). In opposite, fakenews, misinformation and lack of structured data triggers a major informational crisis supplanted by media consortium. This place, occupied by modern journalism, brings him as an actor and reference of news information in society (Verón, 2004; Sodré, 2007). All the aspects mentioned in this introduction will be discussed in more detail in the next sections.

2. The Beginning of Covid in Brazil

In Brazil, for example, the first officially registered case occurred in late February 2020, more specifically in the city of São Paulo (G1, 2020a), practically three months after the official announcement of the cases in China.

Shortly before, in the face of an increasing number of cases being reported in several countries, especially in Europe, and the imminent arrival of the virus in Brazilian territory, on February 4, 2020, for example, the Federal Government of Brazil reached decree a state of emergency because of the coronavirus (Folha, 2020). However, it did not indicate sanitary measures of social distancing, wearing a mask or banning public events.

In a turbulent political moment in Brazil, the Federal Government accuses managers of States and Municipalities of having held Carnival (the largest popular party in the country and one of the best known in the Western world), even knowing the risks involved with agglomerations, and Governors and Mayors indicate that there was no federal recommendation to cancel the festivities.

In this context, some health professionals suggest, for example, that having maintained the Carnival program, even when the virus was circulating in several countries, may have contributed to the spread of the disease in Brazil. Speculation was strengthened on April 2, 2020, when the Brazilian Ministry of Health reported that the first official case in the country would have occurred in January 2020, with a patient from Minas Gerais. The information was denied the next day by the Ministry itself (Veja, 2020).

The Brazilian Carnival, considering the street blocks and parades of the samba schools, officially took place between February 21 and March 1, 2020, and brought together more than 16.5 million people in Salvador - Bahia (Ministério do Turismo, 2020); 15 million in São Paulo (JovenPan, 2020); and 12 million in Rio de Janeiro (Último Segundo, 2020), in addition to thousands of people on the streets of different cities in the country. As usual, the contingent of foreigners and Brazilians moving through national cities was intense. Just as an example, we mention the city of Rio de Janeiro, which received 2.1 million tourists, 22% of whom were foreigners (G1, 2020b).

This intense flow of people between cities, states and countries may have contributed to the spread of the new coronavirus, which was probably already in circulation in several Brazilian regions. That is why many Brazilian scientists and doctors, like Dr. Drauzio Varella2, indicate that canceling Carnival would have been an adequate measure (IstoÉ, 2020).

It was from March 15, 2020 that several Brazilian states adopted measures of social distancing, with a greater or lesser level of restriction of circulation for local inhabitants (Agência Brasil, 2020). In general, social distancing with the suspension of services considered non-essential, such as theaters, cinemas, gyms, shopping centers and churches, was adopted for at least six months.

In São Paulo, the city where the first official case of the disease was confirmed in Brazil, the term “quarantine” was adopted in a decree of March 22, 2020 (Governo de São Paulo, 2020). João Doria, the governor of the State of São Paulo’s wish, which for a long time was the epicenter of the new coronavirus in Brazil, was for the isolation rate to reach 70% (G1, 2020c).

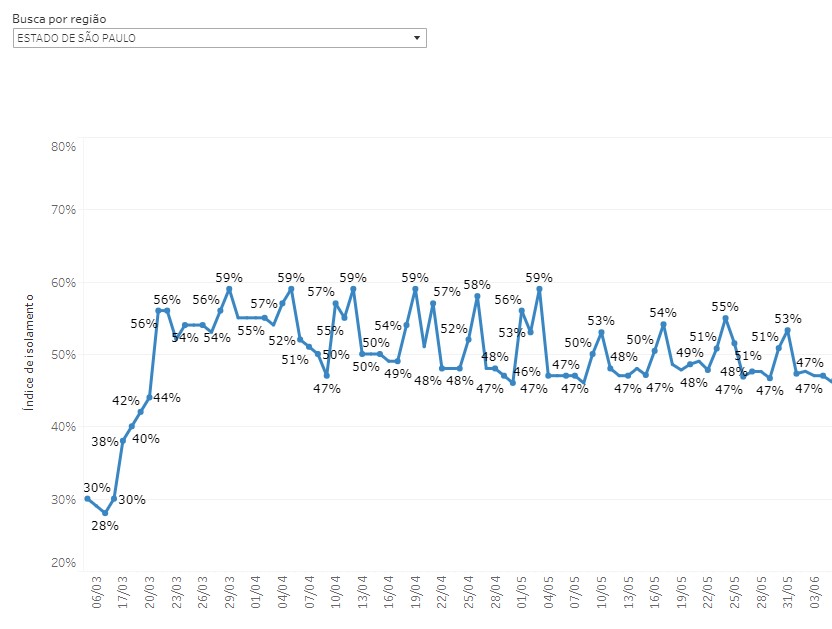

The State started from an isolation rate of 28%, on March 12, 2020, to, in approximately one week, an expressive 56%, on March 21, 2020. However, the 70% mark was never reached. With variations between weekdays (lower isolation rates) and weekends (higher isolation rates), the best mark occurred on March 29, 2020, with 59% (rate that was repeated on April 12, April 19 and May 3), as can be seen in Figure 1.

(Source: https://www.saopaulo.sp.gov.br/coronavirus/isolamento)

Figure 1 São Paulo State Government page presenting the adherence rate to social isolation in the state

During the months of March and April, there was intense political dispute over the coronavirus theme. Many defended “Stay at Home” and others defended what was called “vertical isolation”, in which only the elderly and other people in the risk group would be isolated. Jair Bolsonaro, President of the Federative Republic of Brazil since January 1, 2019, was one of the defenders of this second line of thought, a fact that displeased most state and municipal managers, who understood that the president's word and the measures suggested by him could confuse the population. In other words, Governors claimed that, even suggesting social isolation measures, the president's behavior influenced a significant portion of the population that ended up refusing to accept the imposed measures.

Faced with the misunderstanding between higher authorities of the country, the Federal Supreme Court (STF), on April 15, 2020, decided that states and municipalities would have the power to define rules on isolation (G1, 2020d). The decision, in general, had no impact on the isolation rate in Brazil, but came to be used as justification by President Bolsonaro for not being responsible for the deaths resulting from the contamination caused by the new coronavirus.

In addition, a dispute between Bolsonaro and Doria (Uol, 2020a), the governor considered the president's most staunch critic during the new coronavirus pandemic, took over several digital environments, which may have affected isolation rates in the period, depending on the political spectrum defended by each individual.

Ranging within a margin of 47% to 59% throughout the month of April, in early May, the Government of São Paulo readjusted its expectations and began to seek an isolation rate constantly above 55% (Uol, 2020b). However on May 24, 2020, a Sunday, it was the last time that a 55% isolation rate was recorded in the State of São Paulo. Since then, until the closing of this article, in July 2021, this mark has not been reached.

Despite the obstacles caused by decisions at the municipal, state and federal levels, in addition to several objectives that were not achieved regarding the isolation rate (CNN Brasil, 2020). It can be said that part of the Brazilian population became aware of the importance of avoiding agglomerations, using mask and maintain social distance. This resulted in an increase in the use of ICTs. Some data indicate that in the first three quarantine days, fixed internet consumption grew by 40% (Uol, 2020c) and, during the pandemic, in March 2020, the country hit its peak Internet traffic (Estadão, 2020). Home office, for example, was adopted by 46% of companies during the pandemic (Agência Brasil, 2020a) and, when finished, it is estimated that the percentage of companies that will allow this practice by their employees must be increased by 30% in relation to the period before the pandemic (Agência Brasil, 2020b).

In addition, this increase in the use of the Web caused the number of virtual sales (e-commerce) to raise considerably, as well as the delivery of purchases, which increased 59% due to social isolation (Exame, 2020a). As a result, complaints about fixed broadband providers grew more than 30% compared to 2019 (G1, 2020e), as did Internet scams, by 17%, especially for malicious links that pretended to pass on information about Covid-19 (Terra, 2020).

In this sense, the increased access to ICTs and the increased use of social networks have intensified the process of interaction between individuals. The main attributes of this new environment are the speed and efficiency in the transmission of information (Castells, 2009), which favor the exchange between users. This interaction also tends to be amplified with the mobility and how is instantly provided by mobile devices (Ferreira, 2003), popular devices even in developing countries like Brazil, where around 230 million smartphones are in use today (Época Negócios, 2019).

This phenomenon causes the increase in the use of messaging applications, such as WhatsApp, present in 93% of Brazilian devices (Ventura, 2020). In April 2020, still in the context of the new coronavirus pandemic, based on old complaints and in view of the excessive number of messages containing fake news - which may have affected social isolation during the pandemic of the new coronavirus -, WhatsApp decided to decrease the number of message sharing in an attempt to reduce the spread of fake news (Rosa, 2020). According to Gu, Kropotov, Yarochkin (2017, p. 5):

Fake news is the promotion and propagation of news articles via social media. These articles are promoted in such a way that they appear to be spread by other users, as opposed to being paid-for advertising. The news stories distributed are designed to influence or manipulate users’ opinions on a certain topic towards certain objectives.

Kropotov and Yarochkin (2017, p. 7) also indicate that “fake news in its current incarnation would not be possible without social media sites, as these platforms allow users from various countries to connect with other users easily”.

3. A Brief Retrospective of the Actions of the Brazilian Ministry of Health under the Focus of Communication

In February 2020, the Ministry of Health monitored 20 suspected cases of infection with the new coronavirus in seven Brazilian states (Paraiba, Pernambuco, Espirito Santo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo and Santa Catarina). Another 59 suspected cases had already been discarded after laboratory tests showed negative results. Until, on the 26th of that month, the Ministry of Health confirmed the first case of Covid-19 in Brazil (the first death due to the new coronavirus in Brazilian territory occurred on March 12, 2020) (G1, 2020f). The case was monitored by the Ministry of Health in conjunction with the State Health Department of the State of Sao Paulo (SES / SP) and the Municipal Health Department of the Municipality of Sao Paulo (SMS / SP). He was a 61-year-old man, admitted to Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, in Sao Paulo, on February 25, after returning from a trip to Italy (Oliveira; Ortiz, 2020).

During the press conference that publicized the first case of coronavirus in Brazil, Luiz Henrique Mandetta, the then Minister of Health, stated that Brazil was prepared to test the possible infected and ensure the monitoring and treatment of confirmed cases ( Ministério da Saúde, 2020a). In addition, Mandetta ensured that the Brazilian population would have all the information necessary for everyone to take precautions and due care with hygiene and respiratory etiquette.

In the same line of promise of transparency in relation to communication, the news about the confirmation of the first case published by Saude Agency, of the Ministry of Health, informed that all the actions and measures adopted were in accordance with the protocols of the Ministry of Health and WHO and that daily updates would be carried out, disseminated in collectives and epidemiological bulletins. Two platforms were also released: www.saude.gov.br/coronavirus (https://coronavirus.saude.gov.br/), for more information on the coronavirus; and IVIS Platform (http://platform.saude.gov.br/novocoronavirus/), which presented numbers of discarded and suspicious cases, case definitions and possible changes that occurred in relation to the epidemiological situation (Oliveira; Ortiz, 2020). On the 24th day of October 2020, the latter was no longer available.

In fact, the dissemination of information about Covid-19 has become and continues to be an important ally in combating the virus. The use of ICTs can contribute to the dissemination of strategic information that helps to mitigate the spread of the virus, as indicated by Oliveira (2020), professor of the Professional Masters in Environmental Health and Occupational Health at the University of Uberlândia. The issues of using the means of communication made possible by ICTs and data transparency are included in the Law on Access to Information (LAI), Law No. 12,527 of 2011, whose objective is to ensure the fundamental right of access to public information.

Article 3 of the LAI provides that the procedures provided for therein must respect the basic principles of Public Administration and the following guidelines: observance of advertising as a general precept and secrecy as an exception; disclosure of information of public interest, regardless of requests; use of means of communication made possible by information technology; fostering the development of a culture of transparency in public administration; and development of social control of public administration.

In this sense, it is essential to recognize that, although there has been an attempt to approximate the provisions of LAI regarding the guarantee of access to information about the new coronavirus, there are indications that lead to believe in the lack of transparent communication by the competent public agencies. Such evidence permeates aspects such as the centralization in the holding of press conferences, the dismissal of the Minister of Health, the change in the provision of data on the official platform and the concealment of information, among others.

The press conferences held by the Ministry of Health represented an important step to inform media professionals, as well as to update the public about the numbers of cases and learning about the disease in the country, especially in terms of precautions to avoid the proliferation of the virus.

On March 30, 2020, a letter was sent by the Civil House to the other ministries signaling that the communication of federal actions to combat the new coronavirus would be centralized. Thus, all press conferences of the Ministries or Federal Agencies on Covid-19 should be held in the West Room of the Planalto Palace (Exame, 2020).

Regarding the dismissal of the Health Minister by President Jair Bolsonaro, on April 16, 2020, the former Minister announced it in his official Twitter account. Mandetta and Bolsonaro differed on the ways to fight the pandemic of the new coronavirus, since the first was in line with the WHO guidelines, towards general social isolation, while the second defended the opening of businesses to avoid problems in the economy (Valente, 2020).

The day after the resignation report, oncologist Nelson Teich took the role as Minister of Health in Brasilia. At the ceremony, the new minister reinforced the importance of information about Covid-19 since ignorance generated anxiety and fear in the population. With this focus, he announced his desire to integrate the actions of the Ministry of Health with other ministries, to map related issues, expand knowledge and have more qualified people working together (Ascom Conass, 2020).

On May 15, less than a month after his inauguration, Nelson Teich resigned as minister due to possible disagreement with Bolsonaro, who defended the use of chloroquine, the expansion of activities considered essential and the easing of social isolation (Andrade, 2020). After Teich left, General Eduardo Pazuello took office on an interim basis, becoming the holder in office only on September 16, 2020 (G1, 2020g).

In fact, the changes in the Ministry of Health had a direct impact on the holding of press conferences. For example: press conferences to explain the numbers and present measures to combat the pandemic are no longer daily with Mandetta's departure; the number of interviews fell after Teich left; and such events now count on the participation of second-level technicians from the Ministry, as substitute secretaries, with Minister Pazuello. Furthermore, the format of the interviews changed and the participants did not necessarily answer questions sensitive to the fight against the coronavirus, such as the forecast of the peak of the pandemic in Brazil (Machado; Carvalho; Teixeira; Cancian, 2020).

The departure of two ministries of health in the midst of the pandemic, the lack of a definitive minister of Health in the following months and the involvement of the military in the Ministry of Health was the target of criticism from authorities and experts (Exame, 2020). However, what seems to have been generating discomfort regarding to the procedures adopted by the Ministry of Health was the change in the provision of data and the hiding of information. In early June, there were changes in the publication of data by the Ministry of Health, which, among other things, decreased its quality and quantity.

On June 4, 2020, the portal that released the number of dead and contaminated was removed from the network and, when available again, after 7 pm, it presented only the “new” cases, that is, those registered on the same day. Consolidated numbers and history of the disease since its inception have been omitted; the curve of new cases by date of notification and by epidemiological week; cases accumulated by notification date and epidemiological week; deaths by notification date and epidemiological week; and accumulated deaths by notification date and epidemiological week. Links to data downloads in table format were also eliminated, which allowed the analysis of researchers and journalists.

On June 7, 2020, the return of Covid-19 balance sheet data publication was announced, but the figures presented within a few hours were conflicting. In view of the restricted access to data from the Covid-19 pandemic, a partnership was made between journalists from the G1, O Globo, Extra, O Estado de S. Paulo (Estadão), Folha de S. Paulo and UOL media. Working collectively, the consortium of the press began to collect data from the health departments of the 26 states and the Federal District and jointly released the consolidated numbers of tested cases with positive results for the new coronavirus, in addition to the referring to the evolution and total deaths. In view of the adoption by the Federal Government of measures contrary to LAI principles and guidelines, this unprecedented action represents a possibility for the population to have access to information that should be made available by the Government itself. The work of the Brazilian press ended up receiving an international award for excellence for informing and educating the population about the new coronavirus (G1, 2020h).

It is curious to observe the movement of the Brazilian press in relation to the dissemination of data on the pandemic, as they began to simultaneously report those from the Ministry of Health, traditionally the official source of information, and those of the partnership between the six aforementioned communication vehicles. This disclosure of data from different sources proved to be important because they vary, both in numbers and methodologies, greatly. Vehicles that combat misinformation and facilitate access to public information have sought to disseminate the balance sheets of the pandemic in terms of the evolution of cases in Brazil, the number of deaths and the number of recovered people. However, the news session on the Ministry of Health website prioritizes the disclosure of the number of people recovered.

In addition, in Brazil, media consortium and agencies are created to prevent the proliferation of fake news. Among them, it is possible to highlight the "Projor", "Project Comprova", "Aos Fatos" and "Estadao Verifica", among others, which seek to ascertain the information and disclose whether it is true or false (fact checking). A novelty that emerged in the midst of the pandemic is the “Healthy Internet Project”, developed by TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design), with support from the International Scepter for Journalists and also by Brazilian partners, such as the “Comprova” consortium. This Google Chrome extension allows Internet users to mark whether the content is abusive, to report both misinformation and hate speech, abuse and / or exploitation of fear (Portal Imprensa, 2020).

Considering the multiplicity of data sources and the difficulty in ensuring access to information, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) launched a series of actions to combat what it has called “disinfodemic”. According to UNESCO, Covid-19 led to a parallel disinformation pandemic, which has an immediate impact on all individuals on the planet, being more toxic and deadly than disinformation on other subjects (Posetti; Bontcheva, 2020).

4. Journalism and the Exchange of Information in Times of Pandemic

One of the most striking effects of the coronavirus pandemic in the country is directed towards the unprecedented technologization of social and professional life. Due to social isolation, more people turn to the world wide web and its speed of transmitting information, factors that intensify interpersonal communication, in addition to enhancing economic, political, privacy, learning and sociability aspects, among others. However, the speed of information exchange does not mean that individuals are being properly informed. In fact, this is the process contrary to what is expected from functional journalism (Sodré, 1986; Medina, 1988; Moulliaud, 1997), which can generate misinformation.

The transformations, which are still underway, are possible to be observed through trends in different information processes, such as, for example, the mass use of georeferential data, especially public health data; economic and cultural changes in the media; or even the way of doing journalism, which increasingly tends towards convergence (Jenkins, 2008; Scolari, 2009) and diversification of formats (Manovich, 2001; Bradshaw, Rohumaa, 2011).

Unlike other pandemics throughout history, the new coronavirus does not cause information isolation, since a large part of the Brazilian population is connected, especially through the Internet. Brazil is the fifth country with the largest number of Internet users in the world (Internet World Stats, 2019). There are almost 150 million Internet users, for a population of approximately 211 million inhabitants, which corresponds to 71% of the Brazilian population connected to the network (Reuters, 2020; Internet World Stats, 2020).

As a result of this connectivity, also recognized by mobile telephony, in which 225.16 million users own at least one device (Anatel, 2020), in Brazil there was an attempt by the Ministry of Technology, Science, Innovation and Communications to create an application capable of identify clusters of people (Folha, 2020). This identification would be done through geolocation and data provided by telephone companies and would not need to be installed or authorized by the individual. This monitoring process through movement surveillance strategies is already used in some independent countries and territories, such as the United States, Spain, Singapore, Germany, Israel, South Korea, France, Russia, Austria, Italy, Belgium, and Hong Kong. Each of them uses different specifications, equipment, and degrees of monitoring, such as facial monitoring cameras, monitoring bracelets, thermal cameras, geolocation data provided by telephone operators, drones, and Bluetooth identification (Lemos; Marques, 2020).

In Brazil, as well as in other parts of the world, we live under a kind of guarded freedom, a society of control supported by multiplatform and cyber data. This guarded freedom is, in a way, consented by the user, since less privacy is accepted in exchange for access to information capable of impacting the social, professional, and economic activities of everyone. Nonetheless, in the country, the debate on data protection is old. In 2018, Law No. 13709 was approved, which is the General Law for the Protection of Personal Data (LGPD), which would come into force in August 2020. However, it was postponed to May 2021, through Provisional Measure number 959 (Diário Oficial, 2020), by President Jair Bolsonaro, published on April 29, 2020, in the Federal Official Gazette. In general, the LGPD seeks to establish limits on the use of personal data, to guarantee individual privacy.

On the other hand, one should consider the constant use, intensity, and growth of social networks, in which users supply their accounts with data that can be used by the platforms. During the period of the pandemic, this volume of data has grown due to the increased number of access to social networks. For example, Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp grew 40% during the pandemic (Jornal Contábil, 2020). In addition, there has been a huge increase in the consumption of broadband internet in the country, as previously mentioned. Journalistic programs have also seen an increasing audience (WPP, 2020). According to the survey on Covid-19, carried out in March this year by the Interactive Advertising Bureau in Brazil (WWP, 2020), television is still the greatest source of informational credibility.

Television coverage was recognized by WHO as a key point in the dissemination of information about the Coronavirus pandemic, which gives recognition and credibility to journalistic activity (Giddens, 1990). However, in parallel to this phenomenon that rescues broadcasts as apparently more reliable, there is an opposite movement, disinformation, and fake news (Zattar, 2017).

A shot of fake news can quickly reach thousands of people, without the original source being easily identified. Facts tend to be, on several occasions, less influential than individuals' personal beliefs in shaping public opinion. In this sense, fake news can delegitimize important facts and make it difficult for the general population to understand necessary information, especially for clarifying Covid-19, since it involves public health. In that regard, as stated by Galhardi, Freire, Minayo and Fagundes (2020, online):

“The dissemination of false information and the culture of misinformation in the health area is not new. In 2008, rumors spread about a natural recipe for protection against yellow fever, on social networks and the WhatsApp messaging app. One of the theories disseminated was that the disease was a scam created to sell vaccines. There were still other theories, such as the one that said that the vaccine paralyzed the liver, that mutations of the virus affected the vaccine’s effectiveness, and that the consumption of propolis could repel the mosquito transmitting the disease. During this period, a very diverse and confusing popular reaction was observed. Some ran in search of the vaccine, while others were victims of those who led them to believe that immunization would be ineffective and lead to death.”

A survey conducted by the Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020, which covered 40 countries, from four continents (Europe, America, Asia and Africa), and interviewed 80,155 people, points out that more than half of the sample (56%), is concerned with information received by online vehicles is true or false. This number tends to be higher in Brazil, with 84% of respondents, followed by Kenya (76%) and South Africa (72%). In addition, 40% of respondents in Brazil fear receiving false news from politicians.

Still according to the referred survey, the Brazilian is more concerned with the misinformation coming from messaging applications, such as WhatsApp (36%) than with Facebook, which leads in all other countries surveyed (29%), except in Mexico, Singapore, Malaysia and Chile.

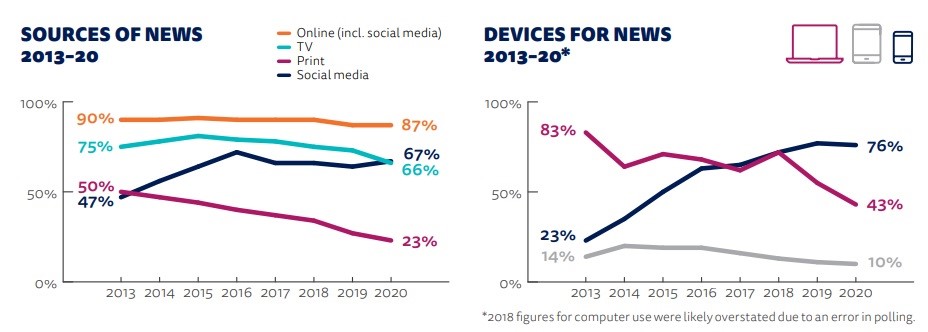

It also shows that almost three quarters of Brazilians (73%) say they are interested in receiving local news about Covid-19. However, considering the 40 countries surveyed by Reuters (2020) again, online information (including social media) has surpassed television in terms of consumption of informational material, such as the news. It also stands out the fact that the most used equipment for news consumption is the smartphone, as can be seen in the following figure 2:

Although people seem to fear disinformation in almost the entire planet, as seen by the data above, Brazil was the third country that consumed the most news online during the pandemic (Mediatalks, 2020). As much of the volume of information accessed by Brazilians comes from social networks, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, some platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp and Google started to intervene and tried to prevent the proliferation of fake news. In April 2020, Facebook flagged 50 million false posts about Covid-19. Google blocked nearly 18 million fake coronavirus emails a day. In the same month, Twitter detected more than 1.5 million users who were spreading fake news (Mediatalks, 2020).

Facing this whole new scenario, Viner (2017, online) claims that

“Now we are living through another extraordinary period in history: one defined by dazzling political shocks and the disruptive impact of new technologies in every part of our lives. The public sphere has changed more radically in the past two decades than in the previous two centuries - and news organizations, including this one [The Guardian], have worked hard to adjust.”

In this context, corroborating what was described throughout the article, Chakrabarti (2018, online) says that:

“[...] social media has enormous power to keep people informed. According to the Pew Research Center, two-thirds of US adults consume at least some of their news on social media. Since many people are happening upon news they weren’t explicitly seeking out, social media is often expanding the audience for news.”

In that regard, according to Marwick and Lewis (2017, online), "the spread of false or misleading information is having real and negative effects on the public consumption of news". In addition, Chakrabarti (2018, online) says that “[...] the battle will never end. Misinformation campaigns are not amateur operations. They are professionalized and constantly try to game the system. We will always have more work to do”. That's what is also complement Gu, Kropotov, Yarochkin (2017, p. 68): “[...] a lie could get around the world much faster than the truth-if the lie played to the lesser, baser instincts of the audience”.

To oppose misinformation and make journalism stronger, Ireton and Posetti (2018, p. 36) propose some options:

“[...] there are the many ways that journalism can respond directly to disinformation and misinformation. These include resisting manipulation, through to investigating and direct exposing disinformation campaigns. But these have to be accompanied by major efforts to improve journalism in general [...].”

In the same way of thinking, Viner (2017, online) indicates that the desire to belong to a group is even more raised on the Internet. In this sense, journalism should not “merely criticise the status quo; we must also explore the new ideas that might displace it. We must build hope”. The author adds that “If people long to understand the world, then news organizations must provide them with clarity: facts they can trust, information that they need, reported and written and edited with care and precision”.

5. Conclusion

This article sought to present data on the new coronavirus pandemic in Brazil and worldwide. It was also exposed the way in which the Federal Government and the State administrations of the country sought to act in this context, especially from the point of view of Communication. The disagreement between government agents and the spread of false news may have contributed to the fact that the requests expressed did not have the expected effect in the country, as, for example, in the case of the social isolation of the population, in which the 70% targets were not reached.

Aspects related to the increase in the use of ICTs in Brazil and in the world were highlighted, especially during the period of social isolation, which also caused the spread of fake news. In this sense, combating disinformation becomes even more important, a constant movement that has generated effects aiming at resolving the practice in the long run. This is a statement based on the power that social networks have today, as Gu, Kropotov and Yarochkin (2017, p. 68) claim: “By now it should be very clear that social media has very strong effects on the real world. It can no longer be dismissed as ‘things that happen on the internet’”.

For example, In July 2021, when the article is being concluded, Brazil still faces around 1,700 Covid-19 deaths per day. Since 2020, when most of this article was developed and submitted for review by the journal, other changes have already taken place in the Ministry of Health of Brazil. The infection and death rate actually declined throughout 2020, but there was a rapid escalation of Covid-19 deaths in the first quarter of 2021. As a result, Eduardo Pazuello was officially dismissed from the Ministry of Health on March 23th, 2021. Despite having the change of minister announced on March 15th, 2021, Pazuello continued to participate in cargo exchange meetings for more than a week, until the cardiologist Marcelo Queiroga assumes the role of Minister of Health (Galzo, 2021).

On June 19, 2021, Brazil surpassed 500,000 Covid-19 deaths. According to CNN Agency data:

“The country reached the mark of 100,00 Covid-19 deaths on August 8th, 2020, 143 days after the registration of the first death. On January 7th, 2021, the number reached 200,000. Just over two months later, on March 24th, 300,000 deaths were confirmed. On April 29th, the rates surpassed 400,000 victims.” (Rocha, 2021, our translation)

Several studies mentioned throughout the article, such as the one by Oliveira (2020), indicate the impacts that true information or fake news may have had on the increase in the contamination of people in Brazil. In this sense, another important point in the fight against disinformation, especially in the case of Covid-19, pandemic and representative public data, was the decision-making of the media The State of São Paulo, Folha de S. Paulo, G1, Extra, Uol and O Globo to come together to recover and continue the dissemination of data on infections, tests and deaths caused by the disease in Brazil. It is also important to recognize the work of fact-checking agencies dedicated to investigating the news about the pandemic. The performance of media consortium and agencies show the possibility of collaboration in order to provide representative data to the citizen who wants to keep informed about the risks associated with the new coronavirus.

Journalism has a fundamental role in the fight against misinformation that undermines prevention care to keep people safe from Covid-19. Considering the scenario presented, there is an incessant search for better information efficiency, which is a challenge, given the large number of posts and shares with incorrect information disseminated among the population, especially in the pandemic period.

Therefore, reinforce studies and practices about direct exposing disinformation campaigns, as suggested by Ireton and Posetti (2018), and offer increasingly reliable information, written and edited with care and precision, as indicated by Viner (2017), long before the pandemic start, seem to be interesting paths and increasingly important for those who want to strengthen journalism.