Introduction

The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has steadily increased 1. In the 1960s, there were an estimated four to five cases of infantile autism per 10,000 births 2; in 2009, this number increased substantially, becoming 60-70 cases per 10,000 births 3. A study carried out in the USA with eight-year-old children, in 2010, estimated the prevalence of one case of ASD for every 68 4; however, in 2014, this number changed to 1 case of ASD for 59 children 5, and in 2016, the prevalence increased again, considering a case for 54 children 6. A study carried out with data from 2019 to 2020 revealed that the prevalence of ASD in the USA is one autistic in every 30 children between 3 and 17 years old in that country 7.

Changes in diagnostic practices or greater knowledge about ASD are factors that stand out in its epidemiology; however, they do not fully explain the increased prevalence of this disorder 8. Genetic factors play an important role in the etiology of ASD; however, studies in this area show that the agreement rate in monozygotic twins is incomplete 9, which shows the association of non-genetic factors in their etiology 10. However, there are gaps regarding the influence of potentially modifiable external factors 11, such as lifestyle, socioeconomic, and demographic conditions. These factors may contribute directly or indirectly to the diagnosis of this disorder, and it is important to carry out investigations on this topic.

Studies have indicated an inverse relationship to what is normally observed for other health conditions, with a tendency to an increase in the prevalence of ASD among people at the high socioeconomic level 12,13. However, others pointed to the low socioeconomic level 14, and still a study that did not find this relationship 15. Socioeconomic and demographic factors have been assessed by education, age, parental occupation, family income, ethnicity/racial groups, gender, socioeconomic status, and family size. However, the results found about socioeconomic and demographic factors and ASD are conflicting, with the main studies being carried out predominantly in high-income countries. Considering the scarcity of studies developed in Latin America and the family’s social and economic impact, caused by the presence of ASD, this study aimed to investigate the association between ASD and socioeconomic factors and demographics in children and adolescents in Northern Minas Gerais - Brazil.

Materials and Methods

This study was carried out in the city of Montes Claros, located in the north of Minas Gerais - Brazil, a medium-sized municipality with approximately 400 thousand inhabitants. This is an excerpt from a case-control study, entitled “Autism Spectrum Disorder in Montes Claros: A Case-Control Study,” which investigated the possible associations between ASD and pre-factors, perinatal, and postnatal. The methodology of this study has been described in detail in previously published works 16,17.

It was decided to calculate the sample size for the case study and independent control, and it estimated odds ratio of 1,9 18, with a probability of 0.18 of exposure between controls; a study power of 80% was established, with a significance level of 0.05 and four controls per case. To mitigate possible losses, the sample size was increased by 10%, and deff = 1.5 was adopted to correct the design effect. The required sample size was defined in 213 cases and 852 controls.

The case group was composed of children/adolescents, aged between 2 and 15 years, who attended the Associação Norte Mineira de Apoio ao Autista (ANDA) and in eight clinics with public and private assistance. Children with a medical report and whose mothers answered the question of the data collection instrument as positive with ASD were considered “Does your child have a diagnosis of ASD?”. The diagnosis of ASD was confirmed by a team of health professionals specializing in ASD, who were based on the diagnostic criteria for ASD proposed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

The control group was made up of neurotypical children/adolescents, with no signs of ASD, who studied in the same schools and had the same age group as the cases in the ratio of four to one. The presence of signs of ASD was considered an exclusion criterion, and screening was performed by the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) 19. It is noteworthy that the M-CHAT was chosen because it is an instrument with a simple format, easy to use and quick to apply. As it is used to screen children aged 18-24 months, mothers were instructed to answer it considering their children in this age group. It is noteworthy that the persistence of specific signs of ASD with increasing age is expected when appropriate interventions are not carried out. After this procedure, 120 children with ASD signs were identified and referred for a better diagnostic investigation.

For data collection, a semi-structured instrument developed from a literature review and reviewed by a multi-professional team was used. This was pre-tested and, after adjustments, applied to the mothers of both groups, by a previously trained team at a place and time defined by the participants. The socioeconomic and demographic variables assessed were divided into four groups: data from the child/adolescents, the family, the father, and the mother, and are described and categorized in Table 1.

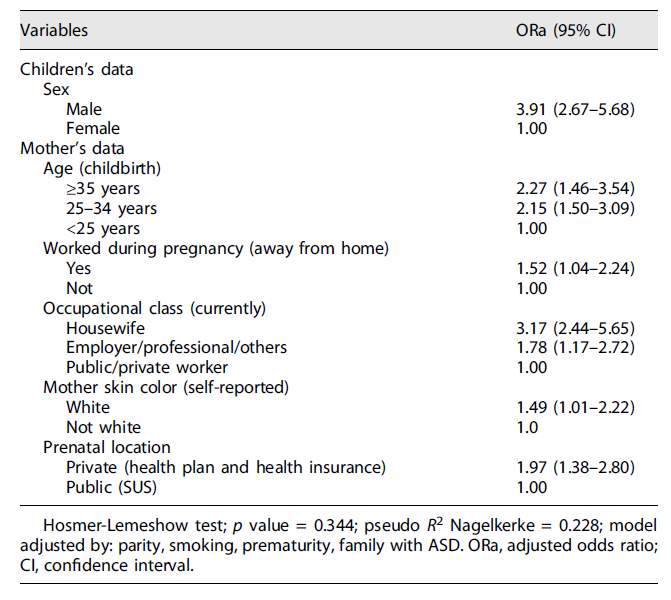

Table 1 Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of children in the case and control groups, Montes Claros, Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2016

Frequency distributions of all variables were constructed, according to the case and control groups. To assess the association between ASD and the other variables, the χ2test was used, and those variables that presented a descriptive level (pvalue) less than 0.20 were selected for multiple analyses. In the multiple analysis, the logistic regression model was adopted with a stepwise procedure, whose association magnitude between the outcome and the independent variables was estimated by the odds ratio, with respective 95% confidence intervals. Adjustment variables were used: parity, smoking, and family with ASD. In assessing the quality of fit of the model, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and the pseudo-R2 Nagelkerke statistic were adopted. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences - SPSS version 23.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) of the State University of Montes Claros (opinion nr 534.000/14), and all those responsible for the children/adolescents signed the Free and Informed Consent Form.

Results

The final sample consisted of 1,134 individuals, of whom 248 were in the case-study group and 886 were in the control group. Of these, 81.0% and 50.7% of the case and control groups, respectively, were male, with a significant difference (p< 0.001).

A similar mean age was observed between the groups: 6.4 years (SD = 3.6) in the case group and 6.6 years (SD = 3.4) in the control group (p= 0.521). The distribution of the age group was also similar between the groups (p= 0.132), and in the total sample surveyed (cases and controls), 44.0% belonged to the age group of 2 to 5 years, 41.4% were aged between 6 and 10 years, and 14.6% were older than 10 years. The groups were also similar in terms of social class (p= 0.115) and the type of school they attended (p= 0.660).

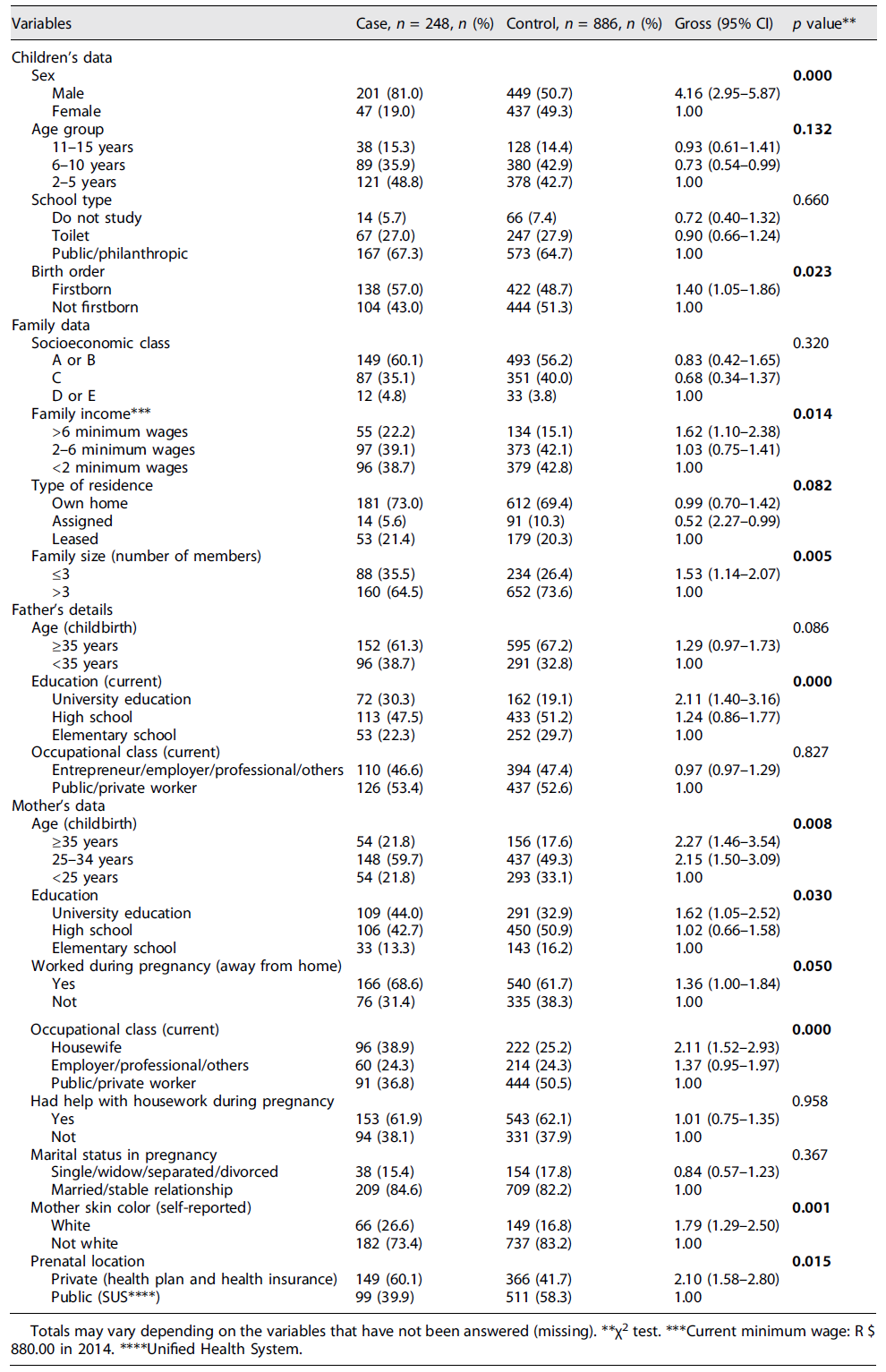

In the bivariate analysis, positive and significant associations with ASD were confirmed for the following characteristics: sex of the child, birth order, family income, family size, education of the parents, maternal age, the mother who worked during pregnancy, occupational class, maternal skin color, and prenatal care (Table 1). In the multiple analysis, it was observed that children and adolescents with ASD remained more likely to be male, being children of mothers aged 25 years or over whose professional occupation was outside the home during pregnancy and who, at the time of the interview, were housewives, businesswomen, or self-employed professionals who declared themselves to be white and who performed prenatal care in private institutions (Table 2).

Discussion

In recent years, interest in studies exploring the impact of socioeconomic factors on health status, including ASD, has steadily increased. This is mainly related to the fact that this disorder is among the top ten causes of disability worldwide in children between 5 and 9 years of age and the constant increase in its prevalence 2,3,5.

In this study, it was observed that children and adolescents with ASD are more likely to be male, children of mothers aged 25 years or over, who had occupational activity during pregnancy, and who were not formally inserted at the time of the interview. In the labor market, who declared themselves to be white and who performed prenatal care in private institutions? It was found that some of these factors facilitate access to health services, being decisive for the diagnosis of ASD and, consequently, for the increase in the number of reported cases.

It was confirmed that children and adolescents with ASD had an approximately four-fold chance of being male, as well as in studies conducted with other ethnically different populations 20-22. The specific factors responsible for the higher prevalence of men with ASD are still unclear.

One possible explanation is that exposure to fetal testosterone affects brain development and behavior. Between the eighth and twenty-fourth weeks of gestation, there is an increase in the level of this androgen, which plays an important role in cerebral masculinization. There is evidence of a relationship between cognitive traits present in ASD and amniotic fetal testosterone level, which is inversely associated with frequency of eye contact at 12 months, vocabulary development at 18 and 24 months, quality of social relations at 48 months, and empathy at 48 and 96 months and is positively associated with interests restricted to 48 months. Therefore, it appears that this androgen plays a role in the development of ASD and its greater prevalence in males.

However, in clinical samples, it was also observed that people with ASD are more likely to be the children of mothers aged 25 years or older. Similar results were found in other studies that pointed out that the prevalence of ASD increases in children of older mothers 23-25. In another study conducted with this same population, it was found that the magnitude of the association was greater when both parents were old 16. Several explanations have been reported to justify the possible relationship of ASD with the increase in the age of the parents, among them the new mutation 26, the epigenetic 10, and complications in pregnancy and/or childbirth, more evident in women with advanced age 27-29. This finding suggests the hypothesis that advanced maternal age may be directly related to the development and diagnosis of ASD.

In this study, parents’ education was not associated with ASD, which is a divergent result from previous studies that identified higher education among parents of children with ASD 30,31. Mazurek et al. 32 pointed out that less education combined with the advanced age of parents are factors significantly associated with delayed diagnosis of ASD, and Fujiwara 33 identified suspicion of children with ASD and less maternal education.

It was observed that children and adolescents with ASD are more likely to be the children of mothers who worked outside the home during pregnancy and who, at the time of the interview, were not part of the formal labor market, being a housewife/liberal professional. These results suggest changes in the employability profile of mothers who, given the greater demands of child care with ASD, may abandon formal work. These findings are in line with other studies 34, which pointed out that, after having their child diagnosed with ASD, some mothers renounced their professional careers to be their child’s main caregiver, while parents were more committed to the profession outside the home. Despite the great individual variations, people with ASD often require from families extensive and permanent care periods 35, requiring a family adjustment to adapt to the new demands faced with an ASD diagnosis 34.

Among family adjustments, the option for a reduced number of family members also stands out, as this study found that, in families with children and adolescents with ASD, the number of members is less than or equal to three, suggesting that the couple had only one child, which has ASD. This fact may be directly related to the child’s birth order with the diagnosis of ASD, in which bivariate analyzes showed that this disorder is more common in firstborn children. However, after adjustments, the birth order lost statistical significance. Results diverged from those of other studies, in which the fact of being the firstborn remained significantly associated with ASD, even after adjustments 36.

Intentionally, in this study, we sought to seek similar groups in terms of social class since the people in the control group attended the same type of school as those in the case group. However, factors related to social class had a significantly higher percentage in the families of children and adolescents with ASD, such as higher family income, mothers of white color, and those who had prenatal care in paid health services. Skin color and prenatal care remained significant even after adjustments.

Yu et al. 12 and Kelly et al. 13 pointed out that the increase in families’ socioeconomic status was associated, proportionally, with the risk of ASD in their children. However, other studies have pointed out that ASD is associated with lower socioeconomic status 11,14, suggesting that such associations mainly reflect a bias in the detection of cases, with an artificially increased prevalence, as some results differ according to the source used to measure the prevalence. In the present study, a diversified data source was used: public, private schools, associations, and public and private clinics, which mitigated possible verification/selection biases.

As for family income, Dodds et al. 37 reinforced that it is not considered a cause for ASD, so this variable possibly reflects the role of potentially correlated cultural and educational factors. They add that access to the health system can interfere with obtaining a diagnosis more easily and, not properly, with the chances of developing ASD. Therefore, this variable deserves attention even though it is not considered a direct cause for ASD, as it interferes with the diagnostic process, allowing it to be earlier in families with higher income and later in those with low income, with little access to diagnostic and treatment services. Thus, where the health system is not universal, there are consequences for the prognosis of the child with this disorder.

It was found that children/adolescents with ASD had twice the chance of their mothers having performed prenatal care in the private network or health plan/health plan. Results were different from those found by King and Bearman 38, who pointed out the fact that individuals whose prenatal care was paid had a reduced risk for diagnosing ASD. Because this variable is related to socioeconomic status, the association found in this study may be due to these families having easier access to diagnostic and treatment services for ASD. It is worth mentioning that, in the region where the study was conducted, there are clear disparities related to the ease of accessing health services and scarce public policies for detecting and monitoring people with this disorder.

The data obtained in this study also showed that there is an increased chance of children and adolescents with ASD being children of mothers who declared themselves to be white. Similar results from other studies that identified a higher prevalence of ASD in white children 39 pointed out that fathers were more likely to be black or Asian and mothers to be of Hispanic origin. These results lead to the question of whether non-white skin color is a protective factor against ASD or whether socioeconomic issues and access to health services contribute to underdiagnosis in these populations.

The limitations of this study are the use, in data collection, of a self-reported semi-structured questionnaire of the mothers, which can be related to a possible memory bias. To mitigate this factor, it was requested, at the time of the interview, that the prenatal card and vaccine booklet confirm the information, and there was consistency between the documents and the mothers’ report. Another limiting factor was the impossibility of confirming the criteria used to diagnose and classify the ASD degrees of individuals in the case group since the diagnosis was made by different professionals; however, by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), all diagnosed individuals are part of the independent sub-classification spectrum.

It is worth mentioning that this study is a pioneer in Latin America; it provided a robust sample with an approximate proportion of four controls per case, a selection of controls representative of the general population, with a screening of children with signs of ASD. Another relevant factor, in the case of a study that investigated socioeconomic conditions, was the fact that the individuals in the group were captured in private and public clinics, which enabled a diversified sample.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) of the State University of Montes Claros with approval number 534.000/14. Written informed consent was obtained from all those responsible for the children/adolescents who signed the “Free and Informed Consent Form.”

Funding Sources

The study was funded by the Research Support Foundation of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG).

Author Contributions

Laura Vicuña Santos Bandeira, Ionara Aparecida Mendes Cezar, Steffany Lara Nunes Oliveira, Ana Júlia Soares Oliveira, Victor Bruno da Silva, and Maria Silveira Nunes participated in the preparation of the instrument and data collection, interpretation of data, and writing of the article. Fernanda Alves Maia and Marise Fagundes Silveira participated in the conception, design, analysis, and interpretation of data and final review of the article. Luiz Fernando de Rezende participated in data analysis, writing, and review of the article.