Introduction

Pancreas is a composite organ with both exocrine and endocrine functions, playing a major role in the digestive process and glucose control and ultimately influencing the nutritional status of an individual. Malnutrition can be defined as a state resulting from lack of intake or uptake of nutrition that leads to altered body composition (decreased fat-free mass) and body cell mass, leading to diminished physical and mental function and impaired clinical outcome from disease, and is more frequently diagnosed by a body mass index <18.5 kg/m2 [1, 2]. While common pancreatic diseases, such as acute pancreatitis (AP), chronic pancreatitis (CP), and pancreatic cancer (PC), may greatly influence the normal pancreatic physiology and contribute to malnutrition, the adequate nutritional approach when those conditions are present significantly influences patients’ outcomes. Despite its importance in gastrointestinal disorders and particularly in pancreatology, it has been recognized that nutritional knowledge among gastroenterologists is suboptimal [3]. For this reason, the aim of this review was to highlight the role of nutrition and to propose a systematic nutritional approach in patients with AP, CP, and PC.

Nutrition in Acute Pancreatitis

AP is an acute inflammatory process of the pancreatic parenchyma with variable involvement of other regional tissues and remote organ systems, being one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders requiring hospital admission [4]. The severity of AP is classified as mild, moderately severe, or severe based on organ failure and local or systemic complications [5]. While the majority of the patients develop mild AP with a self-limited course, up to 20% will develop moderately severe/severe AP with a mortality risk that can be as high as 35% [6]. Regardless of the etiology, initial management of AP consists of supportive treatment aimed at targeting the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) with fluid resuscitation, pain control, and nutritional care [7].

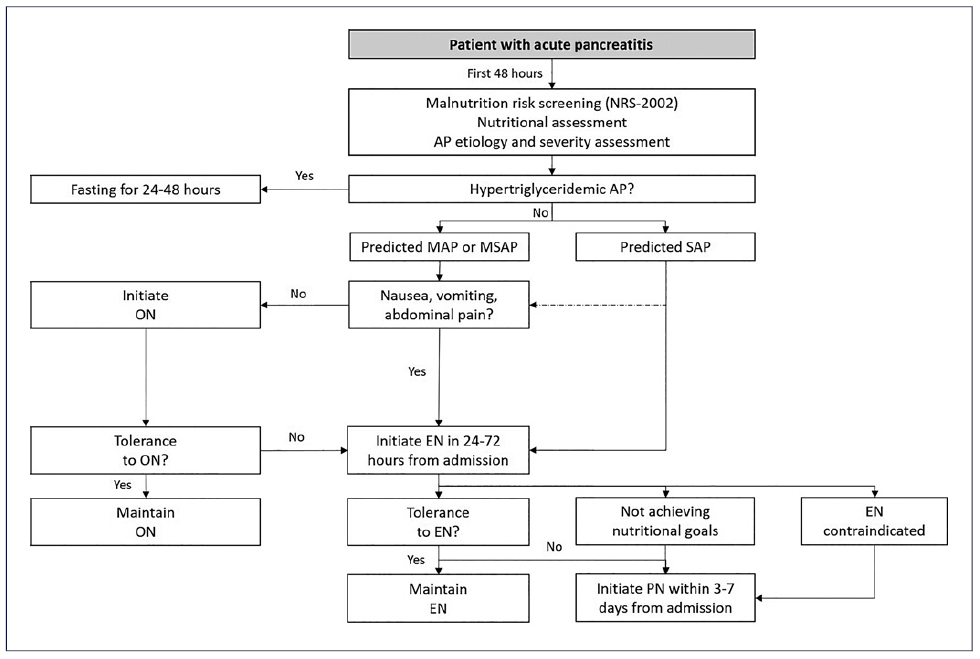

Nutritional care plays a key role in mitigating the sequelae of SIRS. Oral nutrition (ON) and enteral nutrition (EN) are thought to promote the integrity of the gut mucosal barrier by preventing luminal mucosal atrophy, hence reducing gut permeability and the resulting bacterial translocation that potentiates AP-associated SIRS, multiorgan failure, and infection [8]. The SIRS also induces a highly catabolic state that increases metabolic demand, causing a negative nitrogen balance that promotes malnutrition. Therefore, the goals of nutritional care in AP are to prevent malnutrition, correct a negative nitrogen balance, reduce inflammation, and improve outcomes [9]. Based on the current evidence, an algorithm on the nutritional management of patients with AP is provided (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Algorithm suggesting nutritional management in AP. AP, acute pancreatitis; EN, enteral nutrition; MAP, mild acute pancreatitis; MSAP, moderately severe acute pancreatitis; NRS-2002, Nutrition Risk Screening-2002; ON, oral nutrition; PN, parenteral nutrition; SAP, severe acute pancreatitis.

Malnutrition Risk Screening and Assessment in Acute Pancreatitis

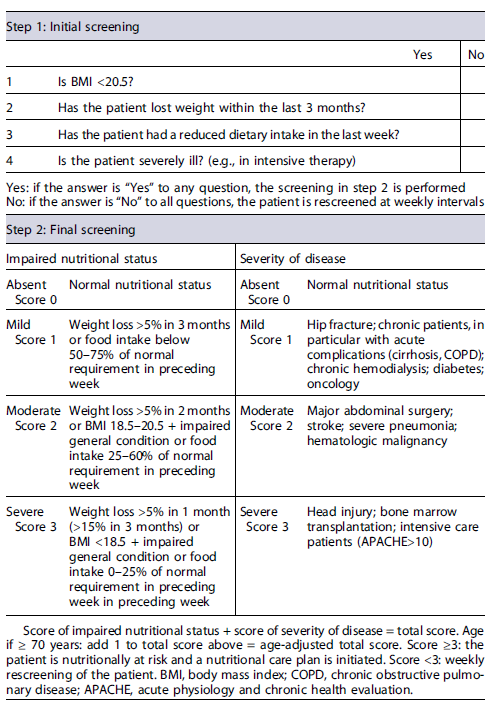

While patients with predicted mild to moderately severe AP should be screened for malnutrition within the first 48 h after admission using an appropriate validated tool, those with predicted severe AP should always be considered at nutritional risk. According to current guidelines, the Nutrition Risk Screening-2002 (NRS-2002) tool is the recommended screening strategy (Table 1) [1, 10]. However, as some risk groups with specific nutritional needs such as alcohol users and obese patients may be incorrectly evaluated when NRS-2002 is used alone, nutritional assessment should also comprise a complete evaluation of the patient, including comorbid conditions, function of the gastrointestinal tract, and risk of aspiration [1]. Subjects identified as at nutritional risk should be referred to the hospital nutrition department to undergo a thorough nutritional assessment, establish a nutritional diagnosis, and aid in defining a nutritional care plan and respective monitoring in conjunction with the multidisciplinary team responsible for the patient’s management.

Table 1 Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS-2002): it includes an initial screening (step 1), with four questions that can be performed by any member of the multidisciplinary team, provided they are properly trained; and a final screening (step 2), performed by a nutritionist, if initial screening is positive

Nutritional Therapy in Acute Pancreatitis Historically, the initial management of AP prioritized “pancreatic rest” with nil per os and total parenteral nutrition (PN) with the rationale that patients would be at risk for worsening clinical course if the pancreas was stimulated by ON or EN. However, many studies showed that timely administration of ON or EN can help protect the gut mucosal barrier and reduce bacterial translocation, thereby reducing the local and systemic complications and death [9, 11-14]. Therefore, in patients with predicted mild or moderately severe AP, ON is recommended as soon as clinically tolerated, independently of serum lipase concentration [7, 15]. Upfront ON with a soft diet seems to be more beneficial regarding caloric intake and equally tolerated compared with clear liquid diets [16-18]. An exception to these recommendations is the management of hypertriglyceridemic AP in which fasting for 24-48 h might be one of the suggested approaches for decreasing serum triglycerides [19]. Even though some patients with AP may develop intolerance to ON, strategies to improve tolerance, like the use of smaller and more frequent meals, adjustment of the dietary fat content and consistency, and use of antiemetic and prokinetic agents, should be considered before changing to EN [9].

In patients unable to tolerate ON, EN is preferred to PN and should be started early, within 24-72 h of admission according to energy requirements calculated through simplistic formulas (25-30 kcal/kg/day), published predictive equations, or indirect calorimetry [20, 21]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that early initiation of EN in patients with AP is associated with significantly improved outcomes compared to PN [21-23].

Regarding optimal type of EN, a standard polymeric diet should be used. The relatively inexpensive polymeric feeding formulations were associated with similar feeding tolerance and appeared as beneficial as the more expen-sive (semi-)elemental formulations in reducing the risk of infectious complications and mortality [24].

Current guidelines suggest using gastric access as the standard procedure as it is cheaper and easier to place and maintain and to implement postpyloric access only in the case of intolerance to gastric feeding or even as the first-line option in patients with a high risk of aspiration. For those patients in whom nasoenteric feeding is not tolerated and/or in whom long-term EN (>30 days) is anticipated, endoscopic placement of a feeding tube should be considered. Patients who can tolerate feeding through nasogastric tube are candidates for a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, while in those who are unable to tolerate it and/or who are at high risk for aspiration, direct percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with jejunal extension are reasonable options [20, 21, 25].

Intolerance to EN is common in moderately severe to severe AP, and strategies to improve tolerance include changing gastric to postpyloric access, changing polymeric formula to a (semi-)elemental formula, and switching from bolus to continuous infusion. Additionally, supplementing enteral formula with soluble dietary fiber might be an option for those patients in whom diarrhea is a bothersome symptom [20, 26]. When these methods have failed to improve EN tolerance, use of medication, like antiemetics and/or prokinetics, can improve tolerance [9, 27, 28].

PN should be administered to patients with AP who do not tolerate EN, are unable to reach targeted nutritional requirements, or if contraindications for EN exist. Contraindications to EN include critically ill patients with uncontrolled shock, uncontrolled hypoxemia and acidosis, uncontrolled upper gastrointestinal bleeding, gastric aspirate >500 mL/6 h, bowel ischemia, bowel obstruction, abdominal compartment syndrome, and high-output fistula without distal feeding access [20, 29, 30]. The optimal timing for initiating PN is not clear but is suggested to be within 3 to 7 days after admission with the decision made on a case-by-case basis.

Regarding PN prescription, a central venous access should be preferred delivering route. Glucose should be the preferred carbohydrate energy source, and its administration should not exceed 5 mg/kg/min. Lipids provide an efficient source of calories as well, and use of intravenous lipids in AP is safe as far as hypertriglyceridemia is avoided. Even though the benefitofprotein supplementation during critical illness is not clear, guidelines recommend that 1.2-2.0 g/kg protein equivalents per day can be delivered progressively. As in all critically ill patients, a standard daily dose of multi-vitamins and trace elements is recommended [19, 20, 29, 30]. Glutamine is a nonessential amino acid that has been studied for its antioxidant properties and should be considered as a supplement only in AP patients with total PN as it may reduce complications and mortality [21, 31].

Even though there is evidence demonstrating high prevalence of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) in AP patients both during their initial hospitalization and in long-term follow-up, the clinical benefitof treatmentof AP-associated EPI with pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) is unknown. Therefore, PERT should only be considered in AP when proven or obvious PEI is present, most likely occurring in patients with pancreatic necrosis and those with alcohol-related AP [32, 33].

Nutrition in Chronic Pancreatitis

CP refers to a syndrome that involves chronic progressive inflammation, fibrosis, and scaring of the pancreatic tissue, resulting in permanent damage to ductal, acinar, and islet cells, with consequent loss of exocrine and endocrine functions [34]. It is a serious condition that can have a severe impact on the quality of life in addition to life-threatening long-term sequelae, such as malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, and PC [35].

Malnutrition in patients with CP is common but often a late manifestation of the disease [36]. Consequences of malnutrition include decreased functional capacity and quality of life and increased risk of developing significant osteopathy, postoperative complications, hospitalization, and mortality [21, 37]. Multiple causes contribute to nutrient deficiency and malnutrition in patients with CP, namely pancreatic insufficiency (both exocrine and endocrine), abdominal pain and related anorexia, delayed gastric emptying (from duodenal stenosis or extrinsic compression from pseudocysts), alcohol abuse, and smoking [38]. Additionally, increased resting energy expenditure has been reported in up to 50% of patients with CP, which leads to a negative energy balance and malnutrition [39].

Malnutrition Risk Screening and Assessment in Chronic Pancreatitis

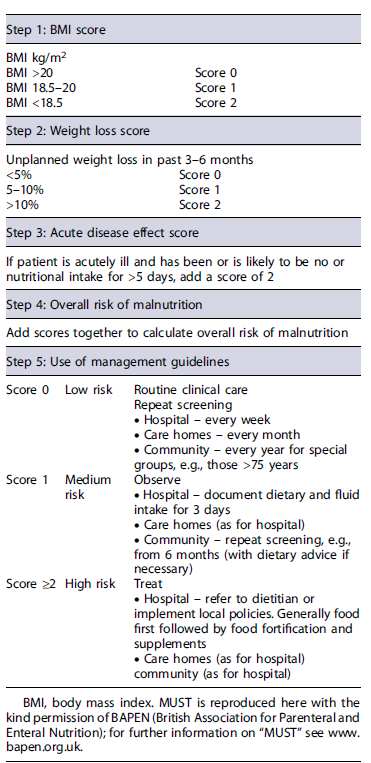

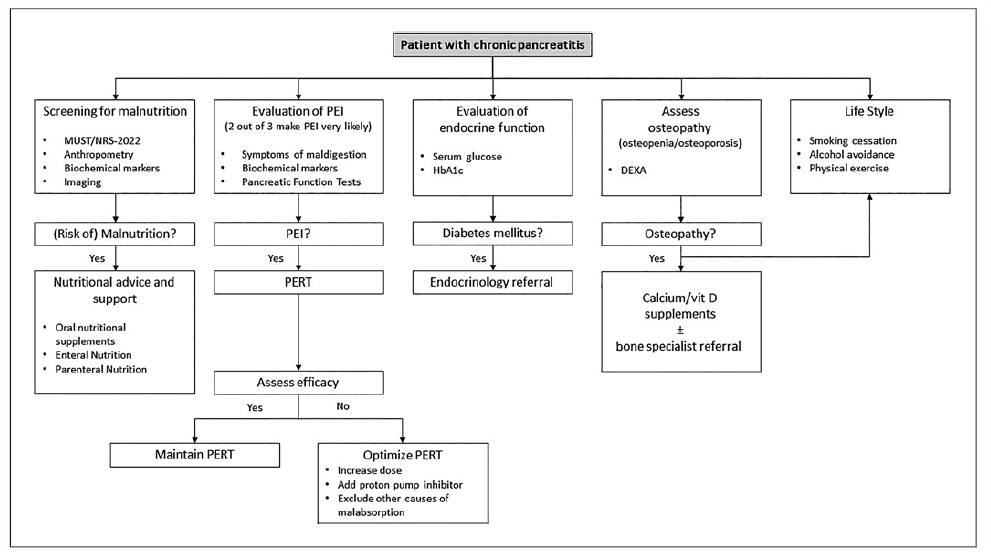

Patients should undergo initial screening either with the community malnutrition universal screening tool (Table 2) or hospital NRS-2002 (Table 1) [19]. Nutritional assessment should be completed with symptoms, anthropometry (body mass index, triceps skin-fold, midarm circumference, and handgrip strength), biochemical evaluations, and body composition (using bioelectrical impedance analysis of CT scan), ideally in the setting of a multidisciplinary group, including dieticians [21]. Body mass index alone is an unreliable marker of malnutrition as sarcopenia may be present in obese patients [40]. Active screening for micro-and macronutrient deficiencies (i.e., folate, vitamins A, D, E, and B12, calcium, selenium, zinc, magnesium, iron, albumin, prealbumin, retinolbinding protein, transferrin) should be performed regularly, at least once a year, or more frequently in those with severe disease and uncon-trolled malabsorption, with prompt supplementation according to recent micronutrient guidelines in case of low concentrations or if clinical signs of deficiency occur [21, 35, 41]. An algorithm regarding the nutritional management of patients with CP is suggested (Fig. 2).

Table 2 Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST): a five-step screening tool to identify adults, who are malnourished, at risk of malnutrition (undernutrition), or obese; it also includes management guidelines which can be used to develop a care plan

Fig. 2 Algorithm suggesting nutritional management in CP (adapted with permission from Pezzilli R, et al. [42]). DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; MUST, malnutrition universal screening tool; NRS-2002, Nutrition Risk Screening-2002; PEI, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency; PERT, pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy; CP, chronic pancreatitis.

Nutritional Therapy in Chronic Pancreatitis

In patients with CP, a low-fat diet is unnecessary and may even predispose to malnutrition, weight loss, and deficiencies of lipid-soluble vitamins [35]. Therefore, while patients with an adequate nutritional status should adhere to a well-balanced diet, those with malnutrition should be advised to consume a high-protein (1-2 g/kg/day) and high-energy diet (at least 35 kcal/kg/day), divided into 5-6 meals per day [21]. The only restrictions to be considered are to avoid diets with high content of fiber (as it may increase symptoms of flatulence and decrease the action of PERT) and to adhere to low-fat diet as a last resort when symptoms of steatorrhea cannot be controlled with optimized PERT [43].

When ON is insufficient for reaching caloric and protein goals, oral nutritional supplements (ONSs) should be prescribed, a practice that is only necessary in about 20% of the patients [21]. As medium-chain triglycerides are less dependent on lipase activity for their absorption, their use in patients with CP has been studied. However, not only do they have an unpleasant taste and gastrointestinal adverse events, but their benefits have not been consistently proved, so they are not routinely recommended [44].

In patients in whom ON with dietary counseling and ONS are unable to improve nutritional status and correct malnutrition, EN is indicated, which occurs in approximately 5% of the patients with CP [19]. In those patients with pain, delayed gastric emptying, persistent nausea or vomiting, or gastric outlet obstruction, the nasojejunal route is the preferred for EN administration. When long-term EN (>30 days) is anticipated, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with jejunal extension, percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy, endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy, or surgical jejunostomy should be considered [21]. Despite being more expensive, (semi-)elemental formulas with medium-chain triglycerides are more adapted to jejunal nutrition and can be used when standard polymeric formulas are not tolerated. When EN is needed and concurrent PEI is present, pancreatic enzymes can be administered with the formula by opening the capsules and suspending the enzyme microspheres in thickened acidic fluid (such as “nectar-thick” fruit juice) for delivery via the feeding tube [21]. PN can be associated with catheter-related infections, septic complications, hyperglycemia, and disruption of the gut mucosal barrier but is needed in <1% of patients with CP [19, 45]. It may however be indicated in patients with gastric outlet obstruction, need for gastric decompression, impossibility to introduce a tube into the jejunum, complex fistulating disease, or in case of intolerance of EN, preferably using a central venous access [35].

Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency

PEI is defined as an insufficient production or secretion of pancreatic enzymes (acinar function) and/or sodium bicarbonate (ductal function) and affects over 70% of patients with CP during their lifetime [35, 46]. Despite the fact that overt steatorrhea is not expected unless the secretion of pancreatic lipase decreases below 10% of normal, nutritional deficiencies with respective clinical consequences can occur earlier in cases of mild to moderate exocrine insufficiency. Other common symptoms of PEI include flatulence, abdominal bloating, cramping, or unexplained weight loss. As patients may voluntarily change their dietary habits to avoid or minimize symptoms, PEI is often asymptomatic [38].

In the clinical practice, a noninvasive pancreatic function test should be performed to aid in the diagnosis of PEI. Fecal elastase-1 (FE-1) is a noninvasive simple test, widely available, requiring only a random sample of formed stool for analysis and is therefore the most frequently used test in this context. Lower concentrations of FE-1 are correlated with higher probability of PEI, but FE-1 may not be suitable for excluding mild to moderate PEI. Despite being less available, the 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test and coefficient of fat absorption are valid alternatives [21]. The presence of two out of three criteria (presence of symptoms of maldigestion, biochemical nutritional deficiencies, and altered pancreatic function tests) makes the diagnosis of PEI very likely [38].

PERT is the cornerstone in the treatment of PEI and should be initiated as soon as PEI is diagnosed or suspected as it has been shown to improve serum nutri-tional parameters, weight, gastrointestinal symptoms, and quality of life without significant adverse events [47]. PERT should be administered along with snacks and larger meals, with a minimum lipase dose of 20,000-25,000 units before snacks and 40,000-50,000 units in larger meals (in this situation, taking one half of the total dose before the meal and the other half in the middle of the meal) [35].

Efficacy of PERT is commonly evaluated by the relief of gastrointestinal symptoms and the improvement of both anthropometric and biochemical nutritional parameters, which occurs in more than a half of patients [47]. When there is no response to PERT, several strategies may be used, namely increasing PERT dosage or adding a proton pump inhibitor and excluding other causes of malabsorption such as lactose intolerance, bile salt diarrhea, or small intestinal bacterial over-growth, which can be present in up to one-third of the patients [48-50].

Pancreatic Endocrine Insufficiency in Chronic Pancreatitis

Annual monitoring of serum glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin levels, even in the absence of diabetes mellitus symptoms, is also appropriate because of the high incidence of pancreatogenic (type 3c) diabetes mellitus in patients with CP, the frequent association of diabetes and PEI, and the impact of undiagnosed diabetes on their nutritional status [38]. Criteria for a diagnosis of T3cDM are fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL or HbA1c ≥6.5%. Na HbA1c <6.5% does not rule out T3cDM due to the limitations of this test in this patient population. Therefore, normal HbA1c (<6.5%) should always be confirmed by fasting plasma glucose. In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia (random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL) or in doubtful cases, results should be confirmed by repeat testing or by the evaluation by a standard 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (2 h fasting glucose ≥200 mg/dL) [35]. This is generally an underappreciated subtype of the disease and can be challenging to manage, particularly by the increased risk of potential life-threatening acute complications and the presence of brittle diabetes with rapid swings in glucose levels in up to 25% of the patients [35, 51, 52]. For these reasons, when diabetes mellitus is diagnosed, prompt referral to endocrinology is advised.

Bone Health and Osteopathy

Another important issue in the nutritional management of patients with CP is the evaluation of bone health as almost 25% of patients are at risk for osteoporosis and about 65% are at risk for osteopathy (either osteoporosis or osteopenia)[53]. There are multiple factors contributing to osteopathy in CP, such as chronic inflammation, smoking and alcohol intake, low physical activity, impaired absorption of vitamin D, and poor dietary intake and sunshine exposure.

The method of choice to identify patients with osteopathy is the dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. While baseline bone density assessment for all patients with CP should be considered, it is certainly indicated in patients with an additional risk factor such as postmenopausal women, those with previous low-trauma fractures, men over 50 years, and those with malabsorption [35].

General measures to prevent osteopathy include adequate consumption of calcium/vitamin D, avoidance of smoking and alcohol, regular exercise, and PERT if indicated. Additionally, daily supplement of vitamin D (800 UI) and calcium (500-1,000 mg) should be considered in patients with osteopenia, in whom dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry should be repeated every 2 years. When osteoporosis is present, referral to a bone specialist with expertise in more specific treatments should be considered [21, 35].

Nutrition and Pancreatic Cancer

PC remains one of the most lethal tumors, being the fourth most frequent cause of cancer-related death and having a 5-year survival well below 10% [54]. Curative treatments, which involve surgery and chemotherapy, are only possible in a minority of patients as localized forms of the disease are diagnosed in just about 20% of the cases [55].

Malnutrition has been described in up to 70% of the patients with PC, with about 40% reporting significant weight loss at the diagnosis [56, 57]. The development of malnutrition in PC is multifactorial and involves different mechanisms: reduced food intake caused by abdominal pain, gastric outlet obstruction, or anorexia; a pro-inflammatory response and activation of several molecular pathways resulting in elevated resting energy expenditure and leading to sarcopenia and cachexia; mal-absorption of nutrients related to PEI; and finally, depression, side effects of the chemotherapy, and anatomical changes due to surgery can greatly affect food intake [58]. Cancer-related malnutrition origins a cascade of consequences, namely increased risk of infections, postoperative complications, and prolonged hospitalization, reduced tolerance or response to chemoor radiotherapy, and reduced performance status, ultimately decreasing quality of life [59].

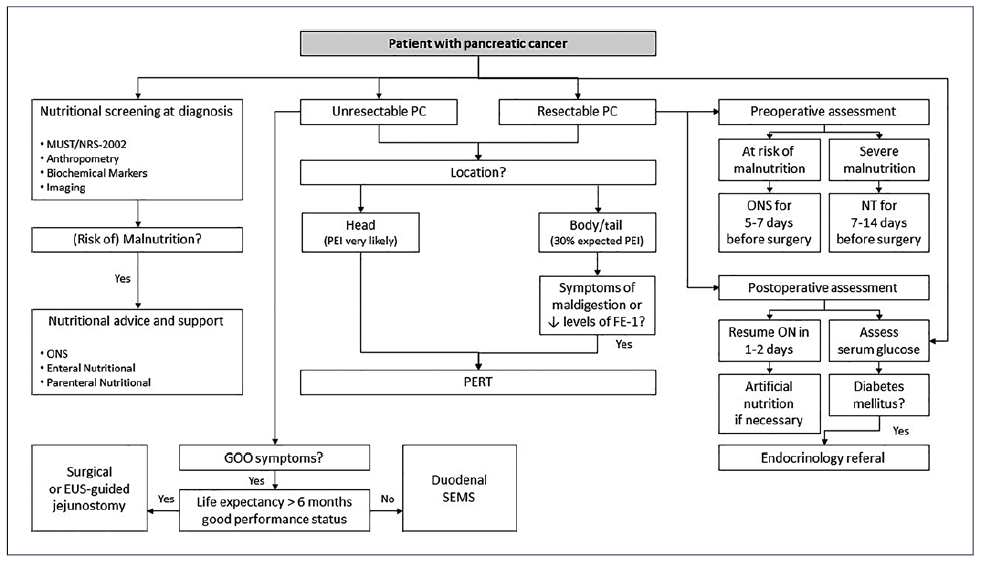

It is now well recognized that early nutritional support in patients with PC can favorably impact survival not only by increasing tolerance and response to disease treat-ments but also by improving quality of life and decreasing postoperative complications [60, 61]. An algorithm with an approach to nutritional assessment of patients with PC is presented (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Algorithm suggesting nutritional management in pancreatic cancer. EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; FE-1, fecal elastase-1; GOO, gastric outlet obstruction; MUST, malnutrition universal screening tool; NRS-2002, Nutrition Risk Screening-2002; NT, nutritional therapy; ON, oral nutrition; ONS, oral nutritional supplements; PC, pancreatic cancer; SEMS, self-expandable metal stent.

Malnutrition Risk Screening and Assessment in Pancreatic Cancer

Latest guidelines on nutritional care in cancer patients recommend that nutritional screening be performed in all cancer patients from the beginning of the disease course, in order to implement nutritional intervention in the form of personalized plans [62]. However, although many nutritional screening tools are available, none of them have been specifically validated for use in PC patients [58]. Some of the suggested tools are the previously referred NRS-2002 (Table 1) and mal-nutrition universal screening tool (Table 2). Several other tools to assess the nutritional status of patients with PC are available, including bioelectrical impe-dance analysis or serum proteins, which are frequently used as markers of poor protein and energy intake, impaired liver synthesis, and a pro-inflammatory status [58].

Patients with a positive screening test for nutritional dysfunctions should then be offered a comprehensive assessment of nutritional intake, symptoms, muscle mass, degree of systemic inflammation, and physical activity. If a deficit in one or more of those topics is recognized, a multidisciplinary team should work togeth-er to correct it [63].

Nutritional Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer

Although a cachexic patient is likely to consume a diet that would be insufficient to maintain weight in a healthy individual, it is recognized that in many patients there is an increase in the metabolism that is responsible for higher caloric needs [64]. When energy expenditure is not individually measured, current guidelines suggest a caloric intake of 25-30 kcal/kg/day and a protein intake of 1.2-1.5 g/kg/day [62].

Nutritional counseling is generally the first step to take and involves increasing the size of meals, the number of snacks, or the energy value of existing meals [64]. If a patient continues to lose weight despite these dietary changes, then ONS may be of value, and despite the low quality of the available evidence, several studies have reported the likely benefit of omega-3 fatty acids on PC cachexia, showing a trend toward stabilization or an increase in weight and in lean body mass [64, 65].

In patients who are unable to tolerate sufficient oral food intake, prompt artificial nutrition is recommended. While EN should be preferred to PN due to lower costs, fewer complications, and ability to maintain the gut barrier, PN has been shown to be of benefit to the majority of patients with pancreatic or advanced cancers [66-68].

Clinical history is essential in identifying obstructive symptoms causing weight loss. Refractory vomiting is the cardinal symptom of gastric outlet obstruction, generally due to malignant infiltration of the duodenum or stomach. In patients with a better life expectancy (>6 months) and good functional status, a surgical or endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy should be performed, while endoscopic placement of a duodenal self-expandable metal stent should be limited to patients with a worse prognosis [69, 70]. Gastroparesis in the absence of anatomical abnormality on CT scan is common, possibly due to direct cancer infiltration of the autonomic nerve fibers and neurohormonal changes. In this setting, prokinetics such as erythromycin or metoclopramide may be useful.

Particularities of Pancreatic Cancer Treatments

In the preoperative setting, patients at risk of malnutrition should be given ONS for at least 5-7 days before surgery [71]. However, patients with severe nutritional risk (NRS-2002 >5, weight loss >10% within 6 months, or serum albumin <30 g/L) should receive nutritional therapy for a period of 7-14 days prior to major surgery even if cancer operations have to be delayed [72].

In the postoperative period, patients can generally resume eating solid food from the first or second day after surgery, but a significant percentage fail to reach caloric and protein requirements due to the occurrence of complications [58]. Early implementation of artificial nutritional support should be considered in mal-nourished patients, in those at high risk of developing malnutrition or with postoperative complications, and in any patients who cannot tolerate at least 50% of their caloric and protein requirement by postoperative day 7 [72].

Regarding chemotherapy, the rate of patients able to complete planned adjuvant treatments ranges from 54%to 72%, having prognostic impact for disease recurrence and survival [58]. While a worse nutritional status is associated with an increased rate of incomplete adjuvant chemotherapy, a better nutritional status is predictive of an enhanced local response to primary tumor as well as a reduced rate of acute complications [73, 74]. Common use of multidrug chemotherapy regimens can certainly impact patients’ nutritional status. If, on one hand, their use may increase toxicity that may impair patients’ feeding ability, on the other hand, more intense chemotherapy can induce better tumor response and, as a consequence, improvement in tumor-related symptoms, inflammatory status, body composition, and nutritional status [75].

Pancreatic Exdocrine Insufficiency and Pancreatic Cancer

Prevalence of PEI in operable PC has been reported as 50-100% [76] and after cancer-related pancreatic surgery as 64-100% [77]. The likelihood of developing PEI in patients with PC depends on different aspects, namely the disease site (head vs. body/tail of the pancreas), the disease stage (local vs. advanced), and the received treatments (surgical resection of the pancreatic head or of body/tail vs. none) [42]. There are several factors contributing to PEI in PC as follows: obstruction of pancreatic ducts due to cancer progression with impaired enzyme and bicarbonate delivery, primary parenchymal loss/resection related to surgery, reduced cholecystokinin-mediated secretion due to duodenal resection, and asynchrony between gastric emptying and bile and enzyme secretion due to surgical denervation and reconstruction [78].

As stated before, several noninvasive methods to diagnose PEI have been described, but in the context of PC, coefficient fat absorption and 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test have the highest accuracy. However, their lack of availability is a barrier for their use in the clinical practice [79]. When the pretest probability of PEI is very high, the presence of symptoms or clinical and laboratory evidence of maldigestion should lead to the decision to start PERT, irrespective of the result of a diagnostic test. Therefore, in patients with pancreatic head cancer, either unresectable or submitted to surgical resection, the expected PEI prevalence is so high that PERT should be started immediately. Conversely, in patients with pancreatic body/tail cancer, PEI should be tested by FE-1 and PERT be started only in the presence of low FE-1 levels or symptoms of maldigestion [42].

While some recent studies showed that PERT significantly impacts quality of life and survival even in the setting of metastatic disease [80, 81], others reported worrying analysis, in which only about 20% of the patients were adequately treated with PERT [82]. In the setting of PC, PERT should be started with higher doses than those used in CP (50,000-75,000 units of lipase with meals and 25,000-50,000 with snacks or supplements). Moreover, as after pancreaticoduodenectomy the secretion of bicarbonate may be impaired and the acidic environment of the duo-denum and proximal jejunum may lead to inefficient activation of pancreatic enzymes, concurrent use of proton pump inhibitors is suggested in operated patients [42].

Pancreatic Endocrine Insufficiency and Pancreatic Cancer

Due to ductal obstruction associated with acinar inflammation and fibrosis replacement of the exocrine pancreas, patients with PC can also exhibit pancreatic endocrine insufficiency, resulting in diabetes mellitus [51]. Plasma glucose should be regularly monitored and if diabetes is diagnosed, endocrinological evaluation should be sought. Importantly, hypoglycemia may occur on glucose-lowering treatment if the patient develops upper intestinal obstruction, cachexia, or steatorrhea, all of which may necessitate dose reduction. On the contrary, hyperglycemic states can be precipitated by chemotherapy infusions in dextrose solutions, by steroids such as dexamethasone used for appetite stimulation, or by PERT which facilitates sugar absorption [83]. Surgical resections for the treatment of PC can also impact endocrine function, which has been described to be worsened, improved, or unchanged after surgery [55]. New onset of diabetes mellitus after surgery may occur after duodenopan-createctomy in up to 40% but is more frequent after distal pancreatectomy [55].

Conclusion

The incidence of pancreatic disorders such as AP, CP, and PC is currently increasing, and adequate nutritional care has been shown to improve patients’ outcomes in all of them. In an era of personalized medicine, tailoring of nutrition care for each patient should be pursued as soon as the diagnostic is established, leading to an appropriate nutritional care plan. As awareness of nutritional issues in pancreatic diseases increases among gastroenterologists, they should become prepared to lead multidisciplinary teams with surgeons, dieticians, endocrinologists, and oncologists involved in the management of these patients.