Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Observatorio (OBS*)

versão On-line ISSN 1646-5954

OBS* vol.10 no.Especial Lisboa jun. 2016

(Social) Media isn’t the message, networked people are: calls for protest through social media

Tiago Lapa* Gustavo Cardoso**

* Assistant Professor in Media and Communication at ISCTE-IUL, Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1649-026 Lisbon, Portugal (tjfls1@iscte.pt)

** Full Professor in Media, Communication and Internet Studies at ISCTE-IUL, Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1649-026 Lisbon, Portugal (gustavo.cardoso@iscte.pt)

ABSTRACT

In recent years, protests took the streets of cities around the world. Among the mobilizing factors were the perceptions of injustice, democratization demands, and, in the case of liberal democracies, waves of discontentment characterized by a mix of demands for better public services and changes in the discredited democratic institutions. This paper discusses social media usage in mobilization for demonstrations around the world, and how such use configures a paradigmatic example of how communication occurs in network societies. In order to frame the discussion, social media appropriation for the purposes of political participation is examined through a survey applied online in 17 countries. The ways in which social media domestication by a myriad of social actors occurred and institutional responses to demonstrations developed, it is argued that, in the network society, networked people, and no longer the media, are the message.

Keywords: social media, social movements, networked communication.

Introduction

Over the last few years, there has been abundant news reports and academic accounts concerning social media use in protests around the world (Al-Azm, 2011; Eltantawy & Wiest, 2011; Shirky, 2011; Tufekci & Wilson, 2012 Castells, 2013). However, sounder understanding is needed in order to identify what is really new in social mobilization. For instance, tags such as Facebook and Twitter Revolutions (Rahaghi, 2012; Sullivan, 2009), which suggest that social media were at the foundations of protests in Arab countries, have probably gone too far. First, they overgeneralize western-like socio-technical processes to other environments, relativizing context. The internet is a globalizing infrastructure enmeshed in global processes, but the relationship between the global and the local is not straightforward and unidirectional. Thus, it should be taken into account societies’ own social stratification systems, considering variables such as socioeconomic status, literacy skills and digital divides. In fact, these variables interweave in multifaceted forms (Warschauer, 2011), especially amid developing countries characterized by clear social and digital inequalities. In addition, they put technology, rather their domestication by people, at the forefront of social mobilization and political processes, oversimplifying the casual nexus between the political and the technological. And probably obscure the concrete reasons behind protests by not fully taking into consideration the importance of the “shared” perception of injustice in protest dynamics. This merely reflects an up-to-date McLuhanian notion that the “medium is the message”, rather than a focus on content and their producers or prosumers, and the networking of people. So, instead of keeping McLuhan’s (1997) catchphrase, it can be sustained that “people are the message” given that social media places communication power in people’s hands and not only on the available media or given message.

Yet, it would similarly be an analytical oversimplification to consider social media as mere digital tools, and disqualified them as factors that can introduce change (MacKenzie & Wajcman, 1999) in political processes, values, beliefs, actions and on our own awareness as autonomous subjects – that is, how people think of themselves, their relation to the world and the capability to autonomously drive, in a somewhat Kantian sense, the course of their lives towards the achievement of particular aims. The diffusion of information and communication technologies (ICT) formed the material foundations for the rise of the network society (Castells, 2000), but beyond representations of Internet’s role in the diverse layers of social and institutional life, there is an interrogation to be addressed: has the dissemination of social media altered ways of thinking and acting in the network society? If both social media and people coproduce each other, then, arguably a Manichean view of who or what is the message - media or people – is unhelpful. Rather, as also suggested by Bennett and Segerberg (2012), the message lies in the relationship between people and technology (and the organizational structures it allows), in the ways social media tools enhance and alter the strengthening of social ties and bring forth connective types of action that bring people, their views and praxis together. In this sense, it will be argued that social media brought novel ways to exert autonomous action, leading to the notion that networked people are, in fact, the message. In order to foster these arguments, practices of political participation and autonomy mediated by the use of social media will be contextualize.

These considerations lead to the question of whether newness can be attributed to social mobilization practices supported by information and communication technologies (ICT) use. To tackle this issue, some start with the assumptions that a crucial difficulty challenging Western-like liberal democracies is the deterioration of citizens’ civic and political engagement (Putnam, 2000; Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, 2002; Wattenberg, 2002) and that the failed strategic communication by politicians and political institutions has left citizens in the cold regarding their perception that they can have an effective political participation (e.g. Dahlgren, 2009). This analytical approach entails the analysis of how new media can enhance traditional and institutionalized engagement patterns (Chadwick & Howard, 2008), among other key indicators of what is perceived as a vigorous democracy (Barber, 1984; Putnam, 2000). Yet, the above assumptions can be challenged by the claim that what is happening is not lesser participation per se, but changes in participatory patterns (Juris & Pleyers, 2009) and citizens’ liaisons with traditional political institutions that previous research has misinterpreted by directing the analytical focus on basically one dimension of political action (Stolle & Hooghe, 2005; Dalton, 2008). Thus, an alternative approach acknowledges not only the multidimensionality of the construct “participation” by differentiating a set of participatory patterns (Zúñiga, Jung & Valenzuela, 2012) but also a possible shift in civic and political cultures.

This entails analyzing how new media reflects such shift and alters participatory forms and even facilitates or supports new ones (Vissers & Stolle, 2013; Castells, 2012; Poell, 2013; Rahaghi, 2012; Bennett & Segerberg, 2011, 2012). In this context, Bennett and Segerberg (2012) make the distinction between collective action, associated with high levels of organizational resources and the formation of collective identities, and connective action based on personalized content sharing across media networks that fosters changes in action dynamics. In turn, one may link this logic of connective action with nascent forms of social agency, specially of ‘alter-globalization activists' (Pleyers, 2013), that is, those who contest neoliberal globalization and propose alternative policies through horizontal and participatory organization models and an emerging global public space. From here a further interrogation emerges: how can the concept of social mobilization be defined and characterized in an age where social media usage1 has become pervasive in the social and political lives of many users around the globe.

The newness of social media in possibilities of autonomization and social mobilization

Some key characteristics of social network sites (SNS) comprise: the mediation of sociability through networks’ morphology, the articulation of pre-existing offline contacts with online connections (Vissers & Stolle, 2013), and the possibility of networking, understood as a process. Therefore, to be connected in a network is a type of action, that is, as hinted by boyd & Ellison (2007: 211), it presupposes agency, directed for the managing of social liaisons for extended periods of time, the expansion of social interactions and people involved in those interactions. However, the implications of boyd & Ellison’s definition of SNS can be extended, by claiming that social media changed not only the number of sustainable connections with others, but brought likewise the perception that is feasible to relate with large numbers of people. Thus, expectedly, in line with Bennett and Segerberg’s (2012) notion of connective action, that perception has consequences in the construction of social reality, either mediated or not, of shared meanings and attitudes, and in individual and collective practices. Furthermore, it can be argued that it forms the social cement of current social movements, allowing goals to be shared by “asserting the importance of social agency in the face of global challenges and against the neoliberal ideology” (Pleyers, 2010: 11).

Socializing through social media constitutes a relatively new practice that can influence the representations of society itself and how social relations are constructed, interrupted, promoted and socially adopted for individual or collective autonomy. Following Kant, society can be viewed as constituted by autonomous, self-possessed individuals, that have the inalienable right to pursue happiness in their own way, where each rational agent must judge every moral principle with his or her own reason, instead of relying in authority actors or institutions alone. In a slightly similar vein, though not embracing this purely rationalistic and individualistic view essentially detached from social processes and relationships, Castells defines autonomy, at the individual or group level, as “the capacity of a social actor to become a subject by defining its action around projects constructed independently of the institutions of society, according to the values and interests of the social actor” (2012: 230-231).

The main argument here is that forms of engagement through connective types of action (Bennett & Segerberg, 2012) may create novel alternatives to exert (individually and collectively) autonomous action. According to Castells, the conversion from individuation to autonomy through networking “allows individual actors to build their autonomy with likeminded people in the networks of their choice” (2012: 231). Here, networked autonomy of individuals is seen in a somewhat different light of the Foucaultian anti-power logic described by Pleyers (2010) to characterize activists of the way of subjectivity that protest against the infiltration of neoliberal capitalism into all spheres of their lives. It is rather seen by Castells as a new form of power. Nevertheless, aside conceptualizations of power, Pleyers seems to be in line with Castells when referring that, for activists, autonomy rises through the construction of liminal spaces of experience that “permit actors to live according to their own principles, to knit different social relations and to express their subjectivity” (Pleyers, 2010: 39). Though, Castells points out the risks of excessive individualization in the Network Society (2000), Rainie & Wellman (2012) associate, in a positive light, the rise of networked individualism with the effect of media networks on the establishment of possibilities of autonomization that circumvent the constraints of institutions and social groups’ strict norms. This matches the notions that technology becomes an integral organizational part, allowing flexibility across various conditions, issues, and scale, and, though the formative element of ‘sharing’, enables individualized public engagement and personalized collective action formations (Bennett & Segerberg, 2012).

Many large global protests that have arisen in the last 15 years have to do with the quality of life in cities (Harvey, 2000), an arena where actors can seek to exercise their autonomy through personalized public engagement with everyday life issues – as exemplified by the recent protests on the streets and squares of Cairo, New York, Istanbul, London, Moscow, Beijing, Hong Kong, Barcelona, São Paulo or Lisbon, where reports about social media usage are persistent (Al-Azm, 2011; Baumgarten, 2013; Castells, 2012; Eltantawy & Wiest, 2011; Ghannam, 2011; Ho & Garrett, 2014; Lim, 2012). An example originates from the Movimento Passe Livre (Free Pass Movement - MPL, its abbreviation in Portuguese)2 (2013) in Brazil, that endorses the Zero Fare (Tarifa Zero) proposal, promoting public funding of public collective transportation instead of charging fares. Likeminded people decided collectively not to pay fares, a joint practice labelled “catracaço” (a neologism derived from the word turnstile or "catraca" in Brazilian Portuguese slang). For the Free Pass movement (2013: 31), “the catracaço is the practical employment of the Zero Fare. It can be done by opening the rear doors of the buses or jumping the turnstiles”. This is an example of creative processes of autonomy, where individuals subverted established “legitimate” resources and regular structural operating rules, aided by digital platforms, operating to own benefit, spreading the word and articulating action with others (Cardoso, Lapa & Di Fátima, 2016).

Though it can be contended that this kind of counter action already existed before the digital platforms advent, there are a few reasons to set it apart from the pre-digital era. First, social media use during Brazilian protests allowed connective action through the creation of links, both with global reach and adapted to the economic context of the country, between individual content producers, loose ties of editorial aggregators and a wide audience. Posts about Brazilian demonstrations reached, at least, 136 million users around the globe (Cardoso, Lapa & Di Fátima, 2016). This illustrates the change in the ways media producers, consumers, mainstream and independent media rebuilt their links and interdependences, pointed out by Pleyers (2010), and in users’ representations towards news reporting and media coverage of events by journalists and citizens. Such processes introduce potential changes in social relations by permitting the formation of communicative autonomy, outside mainstream channels.

Second, as an example of personalized collective action formations, Brazilian protests in 2013 were mentioned on SNS more often than the ongoing soccer event Confederations Cup. Therefore, social media appropriation seems best suited for following ongoing protests, to build transversal coalitions of interests and faster awareness for causes, leveraging political capital. Brazilian regions with higher broadband penetration recorded a higher number of protests, between June 16 and 22, 2013, than areas with low penetration of high-speed Internet (Cardoso, Lapa & Di Fátima, 2016). Finally, there was the role played by SNS in mobilizing people for protests and spreading the word in order to mobilize other potential demonstrators. Although online practices tend to be an extension of offline ones (Poster, 1999; Norris, 2003), the survey of the Brazilian Institute of Public Opinion and Statistics (IBOPE, 2013) revealed that, during the June 2013 protests, 62% of participants adhered to Facebook events calling for action, setting it as an integral organizational structure, and 46% of respondents that used social media to mobilize others, were participating for the first time in a demonstration. In addition, the engagement rate was quite high, given that at least 75% of Brazilian respondents who were called for demonstrations on SNS also mobilized other people online (Idem).

“Social mobilization” can be defined as one particular dimension of political participation, outside the institutionalized and regular political participatory action by voting and militancy, relying on the notion autonomy of social actors. In this regard, social media uses can be related with Dahlgren’s (2009) notion of “civic cultures”, concerning cultural patterns of political participation. Dahlgren examines how the internet has brought new arenas for engagement and participation, such as the blogosphere, Facebook, and internet-based news organizations that promote content creation by citizens and participatory “journalism”. This framework of civic cultures can be applied on social media regarding the following dimensions: literacy (knowledge and skills); the enactment of democratic rules in social network sites; the building of trust and social capital; social media as a potentially richer mediated public sphere; and online identitary expression of citizenship.

Furthermore, Dahlgren also delves about the motivational basis of engagement and mobilization, arguing that not only an individual must reveal cognitive interest, but have an “affective investment” in a certain cause or issue (2009: 83). The perception of injustice that turns into protest (Pleyers, 2010; Castells, 2012; Cardoso, Lapa & Di Fátima, 2016) can be regarded as the affective investment in recent demonstrations throughout the world. Looking at recent protests in various geographical points (Pleyers, 2010; Castells, 2012) the technology allowed the formation of assembly places online that, in turn, connected people with streets and avenues as a locus of protest. Thus, social media appropriation created ties between individual’s ideas, views, calls for action and demonstrations on the streets. It became the “place” where people’s awareness of own ability to exercise autonomy is built because it both enhances the power of individual choices and the perception of one’s role as part of a network.

Analyzing the contributions of networked communication in the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia, Di Fátima (2013) likewise reports the multimodal use of different social interaction platforms online. As indicated by Raoof (2011), Facebook gathered about 2.5 million users (21% of the population) in Tunisia and Twitter, approximately 36 thousand (0.32%) in 2011. However, it is important to point out that those online activists transmitted through other channels their messages to a wider and exclusively offline audience, making a flow of information that transposed from Facebook webpages to the word of mouth in the popular neighborhoods of Tunis and the megaphones in the central squares of the cities of Sfax and Regueb. In turn, it is reasonable to assume that there was a reverse path in the flow of information, since cyber-activists received feedback from the events on the streets to ignite debates online inside and outside of Tunisia and were the first to give international visibility to the protests, until then overlooked by foreign press. The activists gathered on Twitter under the hashtags #freetunisia, #sidibouzid and #tunisia, sharing tips on how to protect from the police in the protests, concerning the most policed areas and the meeting places of demonstrations, and confronting press reports from the media aligned with the regime (Di Fátima, 2013). Following traffic tracking company Back Type3, that belongs to the same media group of Twitter, at least 170,000 messages with the hashtag #sidibouzid were posted between the 12th and the 19th of January by more than 40 thousand users.

Considering these events, social media fashioned spaces of experience online, binding people’s ideas, views and calls for action, that, in turn, connected individuals to other offline gatherings and protests. In this sense, SNS domestication fostered people’s autonomous action once they felt empowered in their choices and gained the perception that their lives are tied and belong to the networks of other actors. Still, in the online diffusion of protest not all actors necessarily exhibit the same level of autonomy, or, to put it in other words, can be regarded as fully autonomous subjects largely acting or circumventing the systemic social influence exerted by norms, institutions and other actors. As pointed out by González-Bailón, Borge-Holthoefer & Moreno (2014), that studied thresholds in the online dynamics of protest diffusion, there are social distinctions between participants, which have different networked influences that affect whether they mobilize or not and the moment of mobilization. Forerunners and initial participants of movements can be regarded as acting more autonomously in their attempt to affect others and pioneer social mobilizations online, while the late majority and laggards might be considered as more prone to normative behavior and social influence from local and global networks in order to be persuaded to participate. Therefore, the capacity for some actors to act autonomously depends on their capability to activate network ties to influence others and, hopefully, generate a chain reaction or a “spiral of protest buzz”.

Notwithstanding individual differences, considering the strengthening of ties between people through social media at the aggregate level, networked communication might change the required critical mass and the time factor or momentum of a social movement, regarding its diffusion threshold when it becomes self-sustaining. Thus, the consolidation of networked communication enmeshed in social mobilizations processes might boost fresh ways to challenge pre-established values, beliefs and institutions, and patterns of collective action that can be considered autonomous and the opposite of the mass communication “spiral of silence” processes described by Noelle-Neumann (1974).

Whereas for Fuchs (2014), following the Frankfurtian critiques of the culture industry, social media can also be viewed as encouraging conformity, his arguments rely to a large extent on the ownership of digital platforms by prevailing corporations and in some features of those platforms. In this framework, new participatory modes of appropriation of emerging media might be overlooked. Furthermore, if there is an emerging networked communication model (Cardoso, 2007) that entails different processes than those steaming from mass communication, the simple transfer of the Frankfurtian and the “spiral of silence” critiques of conformity building to the new media ecology becomes problematic. In fact, research by Moy, Domke & Stamm (2001) advocates that fear of isolation is stronger in small social networks (local networks) than in relation to the population at large (global networks). Moreover, Liu & Fahmy (2009) claim that people quit more easily from an online discussion without the social pressure of complying with the majority, and will speak up if they have a person or reference group that speaks up for them. And while the Frankfurtian and the “spiral of silence” critiques relied on the study of the social influence of western mainstream media, the Brazilian and Tunisian examples discussed above, indicate that protestors’ views can put an end to a spiral of silence, and that the global context of networked communication has its effects in the intersection between both local and global networks.

This seems to validate the statement of Castells that “the morphology of the network is also a formidable source of reorganizing power relations” (2000: 607). Just as for Thompson (1995), in the wake of mass communication, the printing press fostered the appearance of new centers of power. This leads to the issue of whether those politically mobilized through social media can be perceived as less conformist, especially when comparing news consumption through mainstream media with news content sharing on social media. The domestication of SNS features allow simultaneously the building of a “space of collective dissent” (Di Fátima, 2013: 13) towards traditional political and media institutions and the dissemination of arguments and ideas in order to construct trust among users (Maireder & Schwarzenegger, 2012). This might happen especially in the situations in which mainstream media do not fulfill their perceived role regarding the self-professed journalistic criteria of objectivity and impartiality.

Participation and social mobilization through social media

The premise that social media changes not just the number of connections one can maintain over time, but also individuals’ perception of how many people do they relate with, and, hence, the way people participate and promote mobilization, seems plausible. Our data4 revealed that, amongst internet users in the examined countries, SNS usage is very common and diffused: only one tenth doesn’t have a profile in any social network site and among social media users a similar proportion neither reads or write posts. Facebook is the preferred social network site for 77.2% of the surveyed users, followed by YouTube (37.5%), Twitter (36.3%), Google+ (33.9%), LinkedIn (18.9%), Myspace (13.7%), Orkut (8.1%), Hi5 (7.3%) and Weibo (6.4%). At the time of data collection many of those countries had already experienced social mobilizations over the last years, others were yet to experience those, such as Brazil and Turkey that lived through similar experiences between May and June 2013.

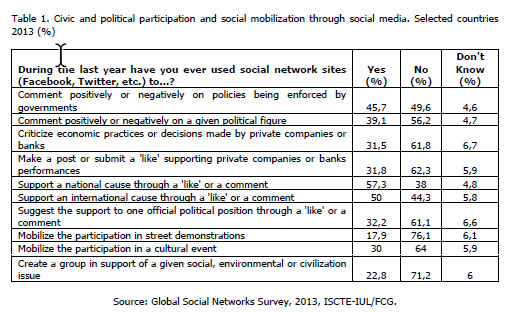

For Burkell et al. (2014: 975), the “information sharing occurs in the context of online social networks that are typically much more extensive than their offline counterparts, including large numbers of weak ties”. This premise is supported by the data obtained in our transnational survey, which found that among the five most used features of social media were: sending messages; posting; chatting; making likes and commentaries on other people’s walls. Those uses display a mix of communication activities and examples of social media appropriation in order to sustain larger social networks, comprising both strong and weak ties. The data indicates that the support of national or international causes through a 'like' or a comment are the most common forms of civic or political participation through SNS. However, group formation concerning social, environmental or civilization issues and mobilization for the participation in street demonstrations are not generalized practices.

Though not involving the majority of respondents, there are some types of use that should also be underlined when analyzing political participation on SNS. Specifically, it is more common to use social media to comment positively or negatively policies being enforced by governments (45.7%) than it is to use it to comment positively or negatively on a given political actor (39.1%). Furthermore, there is a higher percentage of respondents that, over the last year, had used social media to mobilize participation in a cultural event (30%) than to mobilize participation in street protests (17.9%). On average, social media mobilization for cultural events is always higher than calls for protests, a tendency that is particular noticeable in countries where democratic processes are mitigated, such as Russia (31.1% vs 9.7%) or China (30.8% vs 15.8%).

The notion of a platform in which all citizens have access to rational discussion tools around the issues of the society in which they operate, facilitating the flow of information and knowledge, constitutes the ideal of the media as a fourth power, where peoples’ voices, and not just media professionals, reach decision-makers (Hartley, 1992). This would mean the materialization of Habermas’s view of the public sphere. In this sense, there are two divergent perspectives (Vedel, 2009): one, the mobilization approach, sees promise in new media as a way not only to achieve debate outside mainstream media, but to embody civic participation, where common interests allow the raising of opinions, decisions and interventions in specific areas (Morris, 2000). Another, the standardization approach, maintains that the Internet reinforces established powers and the existing levels of political participation (Norris, 2003; Margolis & Resnick, 2000).

In this dispute, Castells (2000) and Pleyers (2010) seem to favor the first perspective due to globalization and the rise of new cross-border social movements in defense of causes such as women and human rights, environmental issues and political democracy, making the Internet an essential tool to disseminate information and for the purposes of organization and mobilization. The transformation of power relations in the “space of flows” must also consider the interaction between political actors, social actors and media business (Castells, 2007: 254). The horizontal flow of information, often involving live updates, might be a clever way to communicate without a trace and create an aura of veracity in contrast with the information that populates the institutionalized political and media arenas (Idem: 251). This horizontal flow and non-restriction of content has, however, less positive implications: the danger of misinformation, especially if propagated by the strongest hubs, since rumors can be quickly repeated and amplified if generated or shared by the most connected members. Still, mobilization processes in social media can be understood as forms of heterodox collective action, not necessarily radical or confrontational, aimed at mobilizing public opinion to exercise pressure on policy makers (Della Porta & Diani, 2006: 165).

The possibility of a flow without the limitations imposed by gatekeepers makes online communication relevant to all stakeholders (citizens and NGO) that aim to make visible denunciations and foster political awareness (Bennett, 2003). If, on the one hand, globalization comprises the risk of hegemony, on the other, allows the visibility of distant areas (in the social sense rather the geographical one). Their issues and social movements can be more easily spread and find supporters in other places of the world. This permits the intertwining of unique local issues with the global world. Citizens think in the context of their own realities but can use social media for the dissemination of their aims and struggles, acting globally (Castells, 2007: 249). Thus, the online realm holds the ability to enable civic and political organization in a way that goes beyond the limits of time, space, local identity and ideology, resulting in the expansion and coordination of activities that possibly could not occur through other means (Bennett, 2003). Taking on Gerlach & Hines’ approach (1968) called SPIN, Bennett regards online activism as segmented, polycentric and integrated: segmented given the fluidity of its borders in relation to formal organizations, where cooperation between non-institutionalized groups and individual activists is a constant; polycentric since there are no leaders but rather coordination centers; and integrated given its horizontal structure.

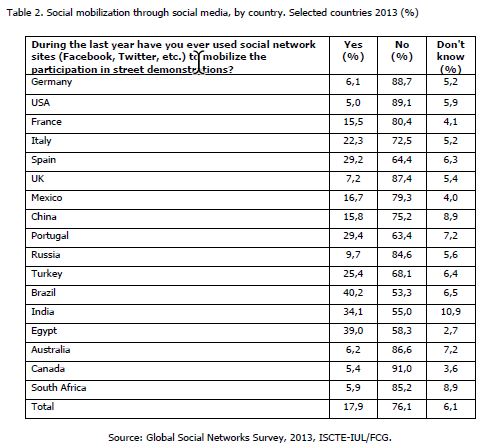

As shown by Table 2, regarding countries where mobilization for protests through social media is higher, three different groups are distinguishable: the first one includes Brazil and Egypt, with near 40% of mobilizers; followed by Spain, Portugal and India, with around 30%, two times above the average, and finally, Italy and Turkey with percentages above 20% of mobilizers. On the opposite side, we find the US (5%), Canada (5.4%), South Africa (5.9%), Germany (6.1%), Australia (6.2%) and the UK (7.2%).

The analysis of the data shows that the label “social media revolutions” shouldn’t be used. First, because in many countries Internet use is still low. Second, even when social media usage is high, its use in social mobilization for protests tends to be confined to specific groups of users, especially, young ones, as also indicated by other studies (Juris & Pleyers, 2009; Bennett & Segerberg, 2012). Regarding the age of users engaging in calls for protests, both the US (40.9%) and the UK (37.5%) present higher percentages of mobilizers in the 18 to 24 years old age group, whereas, considering all countries surveyed, the highest percentage of mobilizers is in the 25 to 34 years old age cohort.

This doesn’t mean that there isn’t innovation brought by social media to social mobilization. Its uses for protest mobilization are higher where social conflict, political instability, economic or financial crisis are more present. It plays a central role both in mobilization, by passing word and inviting people to join in, but also in the usage of its tools to foster one’s weak and strong ties in sustaining the personal social networks of support for the different movements. The data reveals that 51.6% of people who use social network sites can be categorized as having a profile of ‘weak or no activism’ and 48.4% as having a ‘high activism’ profile regarding online mobilization of others to participate in street demonstrations. Among people with ‘high activism’, 87.7% have supported national causes and 82.2% international causes. Among people with ‘low activism’, 50.1% state that they have supported national causes and, 42.9%, international causes. This association between local and national online activism, and the concern of nationals with non-national issues is a known social phenomenon, at least, since the Zapatista movement, in 1994, and also present in the demonstrations of 2003 against the war in Iraq (Castells, 2009; Bennett & Segerberg, 2011). Recently, this phenomenon was perceptible during the Arab Spring (Wilson & Dunn, 2011), in the movements Los Indignados in Spain (Delclós & Viejo, 2012) and Occupy Wall Street (Poell, 2013), and in the Brazilian protests (Cardoso, Lapa & Di Fátima, 2016).

As to the relation between the degree of activism and news following, a similar percentage of people with weak (50.4%) and high (49.6%) activism profiles did follow news on a regular basis. On the other hand, among people with high political engagement there is a higher proportion of users who shared news on social media (71.3%), while those with low activism profiles only represented 28.7% of the total. Therefore, sharing news on sites like Facebook and Twitter seems to be associated with higher levels of activism. This is consistent with other studies which indicate that news consumption on the Internet raises discussion about politics, fostering engagement in the public sphere (Nah, Veenstra & Shah, 2006).

In the Network Society, Media are the Message or Networked people are?

Social media mobilizations for protest bring further implications for social change, because it can be argued that its usage encourages institutional change more easily than mass media and that it might be changing the way people think and act in the network society. Juris & Pleyers (2009) contend that alter-activism represents an emerging global form of citizenship among young people that prefigures wider social changes related to political commitment, cultural expression, and collaborative practice. In this sense people are the message, but it was social media that offered them personal options in ways to engage and express themselves and showed novel ways of political organization. It may as well be considered that networked belonging is increasingly a fundamental cultural trait of the experience of mediation. The reason why belonging through networking has become such an important feature of our social interactions derives from the individual significance that is ascribed to social media usage. Such significance comes from the notion that individuals’ lives are built around socially organized networks, be it the family, friends or colleagues. In turn, such perception has changed people’s subjectivity, by making them aware of their condition as networked individuals. The rise of this type of individuals is seen by Rainie and Wellman (2012) as the natural outcome of practices performed through the mediation of the Internet and its network connectivity.

By linking together offline and online networks, social actors have not just become users of social media, they have built networking cultures that are today a fundamental trait of reflexivity and action, especially in more developed regions. If mass communication fostered the exercise of power through the integration of the individual in the existing institutions of society, networked communication, along with connective action, fosters the building of new institutional settings of power through the networking of individuals. At the same time people are appropriating social media in forums and the streets, governments, traditional and/or formal political actors and institutions seem unable to communicate properly. They are still very much shaped by the mass communication model than by the networked communication model. Not just in their action but also in their subjectivity – the way they think about themselves and the others. That is a fragility for democratic governments because autocratic and non-democratic regimes tend to deal with protests more through real or symbolic violence than by symbolic communication.

Social media are tools that strengthen ties between individuals, but they have not been particularly good at connecting institutions and individuals. They might connect individuals in institutions of power with individuals in counter-power movements, yet, that implies that individuals in power also learn how to incorporate, in their thinking and action, the networked cultures of their citizens. Most contemporary governments perhaps have not understood that they increasingly live in an era in which "networked people are the message", meaning that if people don’t agree with the policies, they will make it clear by communicating it through networks and might propose redesigned policies and post it in order to get the support of others.

What protests of recent years seem to display is the confrontation between different conceptions of power: one influenced by the power of mass communication, in the case of governments, and another influenced by networked communication, in the case of demonstrators. In a certain sense, demonstrators are perhaps regarding governments and political institutions as if they were a search engine, where people are simultaneously making different queries and the “government search engine” must deliver the appropriate answers – and quickly, so people can click and check if they found what they were hoping for. But given that there are always multiple answers available, this means that governments and political institutions are less perceived as the keepers of solutions, but instead as the ones that should produce the links towards them, bridging institutions and multiple constituencies. Thus, institutions of power need not only to formally adopt the tools of social networking but also to change in order to adapt to the networking patterns of thought and action.

The public appeal for change, and non-conformity to the present rules and norms, happens because people sense that their own perception of themselves in relation to their social environment has changed. Individuals don’t merely act in the network, they think and perceive their actions as networked. The cultural innovation brought by social media, along with the appeals to morality or justice, the assertion of democracy and the non-violent challenge of various forms of domination (Wieviorka, 2012), is sustaining the emergence of many social movements. Through social media, using the words of Touraine (2000), many citizens perceive the need to assert publicly their individual and collective right to become free actors, to be able to constitute themselves as subjects, to use creative freedom against social statuses and social roles and to be capable of changing their environment and, therefore, of reinforcing their autonomy. The way people are increasingly thinking about social relations, institutions, power, social change and autonomy as based in networks is the fundamental novelty brought by social media to social mobilization.

Also of notice is the possibility of change in existing communication models, not just because technically there are multiple ways in which people can appropriate communication, but due to social media ability to network different kinds of mediated communication. As suggested by Ortoleva (2004), communication models tend to be connected to cycles of social affirmation. Society shapes communication between actors, giving rise to different ways to communicate, mediated or not, in different historical times. The socially shaped networked communication model (Cardoso, 2007) articulates and binds together mass communication practices, auto-mass communication, one to many mediated communication and interpersonal communication in a multimedia environment. Networked communication combines and connects other communication models, by giving them new features and above all by allowing the use and combination of different possibilities of communication by linking them in a single network.

Social media adoption and domestication created the possibility to connect in one single mediation network all the existing logics and practices of communication. Making possible the connection between what mass media corporations produce and broadcast with what people put on the web and after post in their walls, comment, like and, finally share either with a limited number of people or the whole world by broadcasting it individually. That is why social media acts as a node of all other mediation technologies. Without it people would still have mass and auto-mass broadcast, chatting, etc, but wouldn’t have an aggregate network of communication features that would potentially connect all communication available in current society and, by doing so, giving rise to a networked communication model. Its domestication transformed the prevalent communication model (Silverstone, 1999) because it allows to operate a structural revolution in communication practices and, consequently, in people’s representations of what communication is. Social media networks are the hubs that connect both traditional and new media to shape the networked communication model (Cardoso, 2007).

The study of social media domestication, networked communication, and its ability to connect all communication networks, challenges notions regarding traditional dualities in communication theory: not just the production/reception duality, but also between the mediation process (the media) and the content (the message). McLuhan (1997) argued that the media are the message. By doing so he meant that any single medium induces behaviors, creates psychological connections, and shapes the mentality of the receiver, regardless of the content that medium transmits. In practice, McLuhan makes a conflation between media (form) and message (content), stressing the importance of one over the other. Furthermore, in current networked communication model the appropriation of messages seems to have emancipated from any specific medium. We are not discussing if different people understand different things when exposed to a given message, but that messages (political or otherwise) once entering networks are altered if people understand such changes as necessary for the accomplishment of their autonomous purposes.

In a networked communication environment, whatever the media chosen as an entry point, if the message is not considered the most appropriate by a given group, it will be contested, deconstructed, reassemble, remixed or re-signified by them. This means that the choice of a given media and the “authorship” of content is no longer enough to sustain the message (Sotirovic & McLeod, 2001; Coleman, 1999). The differentiating element in communication is centered more and more in people’s hands, and in the connections they establish with each other, and less in the media available or in the non-remixable content of the messages exchanged. So, in order to better understand social mobilization and social media in our contemporary societies, maybe we should focus more on the power of networked people and less on McLuhan’s catchphrase.

Bibliographical References

Al-Azm, S. J. (2011, Fall). The Arab Spring: Why exactly at this time? Reason Papers, 33, 223–229.

Barber, B. R. (1984). Strong democracy: Participatory politics for a new age. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Baumgarten, B. (2013). Geração à Rasca and beyond: mobilizations in Portugal after 12 March 2011. Current Sociology, 61(4), 457–473.

Bennett, W. L. (2003). New Media Power: the Internet and global activism. In N. Couldry, & J. Curran, (Eds.), Contesting Media Power. Rowman and Littlefield, Available: http://depts.washington.edu/gcp/pdf/bennettnmpower.pdf

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2011). Digital media and the personalization of collective action. Information, Communication & Society, 14(6), 770–799.

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739-768. [ Links ]

Boyd, d., & Ellison, N. (2007). Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230.

Brazilian Institute of Public Opinion and Statistics - IBOPE (2013). 89% dos manifestantes não se sentem representados por partidos (89% of the protesters do not feel represented by parties). Brazil, São Paulo. Available: http://www.ibope.com.br/pt-br/noticias/Paginas/89-dos-manifestantes-nao-se-sentem-representados-por-partidos.aspx

Burkell, J., Fortier, A., Wong, L. L. Y. C., & Simpson, J. L. (2014). Facebook: Public space, or private space?. Information, Communication & Society, 17(8), 974-985. [ Links ]

Cardoso, G. (2007). The Media in the network society: Browsing, news, filters and citizenship. Lisbon: CIES. [ Links ]

Cardoso, G., Lapa, T., & Di Fátima, B. (2016). People Are the Message? Social Mobilization and Social Media in Brazil. International Journal of Communication, 10, 3909–3930.

Castells, M. (2000). The rise of the network society. The information age: economy, society and culture. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2007). Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. International Journal of Communication, 1, 238–266.

Castells, M. (2009). The power of identity. The information age: economy, society and culture. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Castells, Manuel (2011), Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2012). Networks of outrage and hope: social movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge: Polity. [ Links ]

Chadwick, A., & Howard, P. N. (Eds.) (2008). Routledge handbook of internet politics. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Coleman, S. (1999). The new media and democratic politics. New Media & Society, 1(1), 67-77. [ Links ]

Dahlgren, P. (2009). Media and political engagement: Citizens, communication, and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dalton, R.J. (2008). Citizenship norms and the expansion of political participation. Political Studies, 56(1), 76–98.

Della Porta, D. & Diani, M. (2006). Social Movements – an introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Delclós, C., & Viejo, R. (2012). Beyond the indignation: Spain’s Indignados and the political agenda. Policy & Practice, 15, 92–100.

Di Fátima, B. (2013). Revolução de Jasmim: A comunicação em rede nos levantes populares da Tunísia. Temática, 9(1), 1–15.

Eltantawy, N. & Wiest, J. B. (2011). Social media in the Egyptian revolution: Reconsidering resource mobilization theory. International Journal of Communication, 5, 1207–1224.

Fuchs, C. (2014). Social media: A critical introduction. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Ghannam, J. (2011). Social media in the Arab World: Leading up to the uprisings of 2011. Washington, DC: CIMA. [ Links ]

González-Bailón, S., Borge-Holthoefer, J. & Moreno, Y. (2014). Online networks and the diffusion of protest. In G. Manzo (Ed.), Analytical sociology: actions and networks. Chichester: Wiley.

Hartley, J. (1992). The Politics of Pictures: the creation of the public in the age of popular media. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (2000). Spaces of Hope. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Hibbing, J., & Theiss-Morse, E. (2002). Stealth democracy: Americans’ beliefs about how government should work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ho, W., & Garrett, D. (2014). Hong Kong at the brink: emerging forms of political participation in the new social movement. In J. Y. S. Cheng (Ed.), New trends of political participation in Hong Kong. Kowloon: University of Hong Kong, 347–384.

Juris, J. S., & Pleyers, G. H. (2009). Alter-activism: emerging cultures of participation among young global justice activists. Journal of Youth Studies, 12(1), 57-75. [ Links ]

Lim, M. (2012). Clicks, cabs, and coffee houses: Social media and oppositional movements in Egypt 2004–2011. Journal of Communication, 62(2), 231–248.

Liu & Fahmy (2009). Exploring the spiral of silence in the virtual world: individuals’' willingness to express personal opinions in online versus offline settings. Journal of Media and Communication Studies, 3(2), 45-57.

MacKenzie, D. & J. Wajcman. (1999). Introductory essay: The social shaping of technology. In D. Mackenzie & J. Wajcman (Eds.), The social shaping of technology. UK.: Open University Press.

Maireder, A., & Schwarzenegger, C. (2012). A movement of connected individuals: social media in the Austrian student protests 2009. Information, Communication & Society, 15(2), 171–195.

Margolis, M. e Resnick, D. (2000). Politics as Usual. The Cyberspace “Revolution”. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

Matsuo, H., Mcintyre, K. P., Tomazic, T., & Katz, B. (2005). The Online Survey: Its contributions and potential problems. Proceedings of the Joint Statistical Meetings of the American Statistical Association, 3998–4000.

McLuhan, M. (1997). Understanding media: the extensions of man. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Morris, D. (2000). Vote.com. Los Angeles: Renaissance Books. [ Links ]

Movimento Passe Livre - MPL (2013). Não começou em Salvador, não vai terminar em São Paulo (Not started in Salvador, will not end in São Paulo). In Cidades rebeldes: passe livre e as manifestações que tomaram as ruas do Brasil (Rebel cities: Zero tariff and demonstrations in Brazil). Brazil, São Paulo: Boitempo.

Moy, P., Domke, D. & Stamm, K. (2001). The spiral of silence and public opinion on affirmative action. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 78(1): 7–25.

Nah, S., Veenstra, A., & Shah, D. (2006). The Internet and anti-war activism: a case study of information, expression, and action. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(1), 230–247.

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974), The spiral of silence: a theory of public opinion. Journal of Communication, 24(2): 43–51.

Norris, P. (2003). Preaching to the Converted? Pluralism, Participation and Party Websites. Party Politics, 9, 21-45. [ Links ]

Ortoleva, P. (2004). O Novo Sistema dos Media. In J.M., Paquete De Oliveira, G. Cardoso, G. & J. Barreiros (Eds.), Comunicação, Cultura e Tecnologias de Informação. Lisbon: Quimera.

Pleyers, G. (2010). Alter-globalization: Becoming Actors in the Global Age. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Poell, T. (2013). Social media and the transformation of activist communication: exploring the social media ecology of the 2010 Toronto G20 protests. Information, Communication & Society, 17(6), 716–731.

Poster, M. (1999). Underdetermination. New Media & Society, 1(1), 12–17.

Rainie, Lee & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked. The New Social Operating System. Massachussets: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Pridmore, J., Falk, A., & Sprenkels, I. (2013). New media & social media: what’s the difference. New Media and International Business, 1-3.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. [ Links ]

Rahaghi, J. (2012). New tools, old goals: comparing the role of technology in the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the 2009 Green Movement. Journal of Information Policy, 2, 151–182.

Raoof, R. (2011). The internet and social movements in North Africa. In Global Information Society Watch - Internet rights and democratization, 38-41. Available at: http://giswatch.org/sites/default/files/gisw2011_en.pdf

Shirky, C. (2011). The political power of social media: Technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign affairs, 28-41. [ Links ]

Silverstone, R. (1999). Why study the media? London: Sage. [ Links ]

Sproull, L., & Keisler, S. (1992). Connections: new ways of working in the networked organization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Stolle, D., Hooghe, M., & Micheletti, M. (2005). Politics in the supermarket: Political consumerism as a form of political participation. International Political Science Review, 26, 245–70.

Sotirovic, M., & McLeod, J. M. (2001). Values, communication behavior, and political participation. Political Communication. 18(3), 273-300.

Sullivan, A. (2009). The revolution will be twittered. The Atlantic (June 3). Available: www.theatlantic.com/daily-dish/archive/2009/06/the-revolution-will-be-twittered/200478/

Thompson, J. (1995). The media and modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Touraine, A. (2000). A Method for Studying Social Actors. Journal of World Systems Research, Fall/Winter 2000 Special Issue. Available: http://jwsr.ucr.edu

Tufekci, Z., & Wilson, C. (2012). Social media and the decision to participate in political protest: Observations from Tahrir Square. Journal of Communication, 62(2), 363-379. [ Links ]

Vedel, T. (2009). The Internet and the 2007 French Presidential Election. Still the Time of Old Media? In G. Cardoso, A. Cheong & J. Cole (Eds.), World Wide Internet: Changing Societies, Economies and Cultures. Macau: Universidade de Macau.

Vissers, S., & Stolle, D. (2013). The Internet and new modes of political participation: Online versus offline participation. Information, Communication & Society, 17(8), 937–955.

Warschauer, M. (2011). A literacy approach to the digital divide. Cadernos de Letras, 28, 5–18.

Wattenberg, M. (2002). Where have all the voters gone? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Wieviorka, M. (2012). The Resurgence of Social Movements. Journal of Conflictology. Available at: http://journal-of-conflictology.uoc.edu

Wilson, C., & Dunn, A. (2011). Digital media in the Egyptian Revolution: Descriptive analysis from the Tahrir data sets. International Journal of Communication, 5, 1248–1272.

Zillien, N., & Hargittai, E. (2009). Digital distinction: Status‐specific types of internet usage. Social Science Quarterly, 90(2), 274-291. [ Links ]

Zúñiga, H. G. de, Jung, N., & Valenzuela, S. (2012). Social media use for news and individuals’ social capital, civic engagement and political participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(3), 319–336.

NOTES

1 While new media and social media are intimately interconnected, they are not interchangeable terms (Pridmore, Falk & Sprenkels, 2013), since not all new media allows participatory practices. Levinson (2012) stresses the differences by claiming the necessity to distinguish the ‘new’ new media, a term that is arguably more interchangeable with the notion of social media. Social media differs from other media in many aspects such as interactivity, visibility, unfiltered peer to peer communication, participation, control and sociability (Pridmore, Falk & Sprenkels, 2013). In addition, social media can be differentiated from social network sites, following the conceptualization of the former as tools, and of the latter as, specifically, structured forms of engagement, as suggested by boyd & Ellison (2007). However, they can both be regarded as a subset of new media and of Internet itself. The Internet is not a mere information technology, since it is likewise a social technology that promotes both socialization and sociability (Sproull & Keisler, 1992). For the purposes of this paper the terms new media and social media are used, in general, interchangeably, notwithstanding the acknowledgement that to understand the forms of communication it is important to look at both the medium and the message.

2 Though MPL was acknowledged by the press as a new social actor in demonstrations, these kinds of protests in Brazil did not happen out of the blue since similar movements have been endorsing actions towards a zero fare for public transportation for at least the past ten years (Silva, 2013).

3 http://blog.backtype.com/2011/01/analysis-of-the-tunisia-twitter-trend/

4 The data in the present study, regarding social media use on seventeen countries, was obtained through a self-administered survey online during the first trimester of 2013. Country selection aimed at the inclusion of some major contributors to the overall global population of internet users and of diversity, getting societies from all continents and major regions and the most spoken languages online into the sample. These led to the inclusion of the following countries: Brazil, Portugal, Spain, Mexico, USA, Canada, UK, Australia, South Africa, China, India, Egypt, Turkey, France, Italy, Germany and Russia. The sample is composed by 5582 validated questionnaires of ordinary internet users aged 15 and over (no upper age limit). As with other online surveys there were challenges and limitations regarding nonresponse, self-selection and the use of inferential statistics to analyze data collected though nonprobability sampling (Matsuo et al., 2005). To mitigate such problems a weight was calculated and applied to the data in order to achieve a greater reliability and better comparability between countries. This weight was calculated using the results of representative surveys, considering the proportion of internet users in each country, by gender and age. Traditionally, the latter is, along with education, one of the greatest explanatory factors of internet usage (Zillien & Hargittai, 2009).