Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais

versão On-line ISSN 2182-7435

Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais no.111 Coimbra dez. 2016

https://doi.org/10.4000/rccs.6467

ARTIGO

Methods of Studying Economic Decisions in Private Households*

Métodos de estudo das decisões económicas em agregados familiares

Méthodes pour étudier les décisions économiques dans les familles

Erich Kirchler*, Laura Winter**, Elfriede Penz***

* Faculty of Psychology, University of Vienna. Universitaetsstrasse 7, A – 1010 Vienna, Austria erich.kirchler@univie.ac.at

** Faculty of Psychology, University of Vienna. Universitaetsstrasse 7, A – 1010 Vienna, Austria laura.winter@univie.ac.at

*** Institute for International Marketing Management, Vienna University of Economics and Business Welthandelsplatz 1, A – 1020 Vienna, Austria elfriede.penz@wu.ac.at

ABSTRACT

Research on joint decision-making processes in households is particularly relevant for marketing, especially for understanding who decides what to buy in purchasing decisions and how decision processes evolve. However, the investigation of such complex processes requires adequate research methods to account for the dynamics in close relationships. We provide a critical overview of past research in the arena of economic decision-making among couples, concentrating on methodological issues. After describing different types of decisions we proceed by describing findings on interaction dynamics, including the nature and occurrence of conflicts. In reviewing relationship structures we focus on the dimensions of harmony and power. The descriptive process model utilized includes the partners’ use of influence tactics, as well as the emergence of utility debts at the end of a decision-making process. Reviewing the adequacy of various research methods, observational and survey techniques are discussed as conventional psychological research methods. The Vienna Partner Diary is introduced as novel method and suggested as being useful for collecting data on the complex interaction processes in the everyday life of couples.

Keywords: couples, decision-making, family economy, financial management, research methods

RESUMO

O texto fornece um panorama crítico da investigação realizada na área da tomada de decisão entre cônjuges, concentrando-se nos aspetos metodológicos. Descreve diferentes tipos de decisões e retira conclusões sobre as dinâmicas da interação no seio de casais, incluindo a natureza e a ocorrência de conflitos. Discute a adequação de diversos métodos e técnicas de investigação, observação e pesquisa enquanto métodos de investigação psicológica convencional. A investigação no âmbito de processos de tomada de decisão conjunta em agregados familiares é particularmente importante para o marketing, especialmente para entender quem decide o que comprar e como se desenvolvem os processos de decisão. No entanto, a investigação de processos tão complexos requere métodos adequados que deem conta das dinâmicas nas relações próximas. Procuramos fornecer aqui um panorama crítico da investigação realizada na área da tomada de decisão entre cônjuges, concentrando-nos nos aspetos metodológicos. Depois de descrever diferentes tipos de decisões, retiramos conclusões sobre as dinâmicas da interação no seio de casais, nomeadamente sobre a natureza e a ocorrência de conflitos. Na análise das estruturas dos relacionamentos concentramo-nos nas dimensões de harmonia e de poder. O modelo utilizado para descrição do processo inclui a utilização pelos casais de táticas de influência, bem como o surgimento de dívidas após um processo de tomada de decisão. O texto discute a adequação dos diversos métodos e técnicas de investigação, observação e pesquisa enquanto métodos de investigação psicológica convencional. Apresenta-se o Estudo por Diário de Viena (Vienna Partner Diary) como novo método, salientando-se a sua utilidade na recolha de dados sobre os complexos processos de interação do dia a dia dos casais.

Palavras-chave: casais, economia da família, gestão financeira, métodos de investigação, tomada de decisão

RESUMÉ

La recherche sur les procédures de décision conjointe dans les familles est d’une importance particulière en ce qui concerne le marketing, permettant de comprendre qui décide de quoi acheter dans les décisions d’achats et comment les processus de décision évoluent. Toutefois, la recherche sur des processus si complexes exige des méthodes de recherche adéquates permettant de tenir compte des dynamiques existant dans ces rapports étroits. Nous proposons une approche critique globale des anciennes recherches dans le domaine de la prise de décisions économiques des couples, nous penchant sur des questions méthodologiques. Après avoir décrit différents types de décisions, nous sommes passés à la description de résultats des dynamiques d’interaction, y compris de la nature et de l’occurrence de conflits. En ce qui concerne les structures de la relation, nous nous centrons sur les dimensions d’harmonie et de pouvoir. Le modèle de description du processus que nous avons utilisé comprend le recours par les partenaires à des tactiques d’influence, ainsi que l’émergence de dettes aux services à la fin du processus de prise de décision. En analysant l’adéquation de plusieurs méthodes de recherche, nous nous sommes penchés sur les techniques d’observation et d’analyse qui sont les méthodes de recherche psychologique conventionnelle. Le Journal des Partenaires de Vienne est introduit comme nouvelle méthode; nous suggérons qu’elle est d’utilité pour colliger des données sur les processus complexes d’interaction dans la vie quotidienne des couples.

Mots-clés: couples, économie de la famille, gestion financière, méthodes de recherche, prise de décisions

Introduction

Economic decision-making in private households is a relevant topic from the perspective of marketing for understanding how partners in close relationships manage everyday life, as well as from a micro-economic standpoint of investigating money management among partners. When speaking of private households, research typically revolves around couples, both with or without children, who live under one roof. Often, economic decisions need to be made that will demand in-depth analyses, lead to uncertainty and force the couple to weigh different alternatives, so that in the end specific actions can be taken. Decision-making processes are often characterized by differences of opinion between partners, which can cause disagreements and conflicts.

In order to understand decision-making dynamics, it is necessary to differentiate between different areas of decision-making, as well as to investigate characteristics of romantic relationships and interaction processes between partners. To this end researchers have to find adequate research methods that acknowledge that economic decision-making in private households occurs simultaneously with other events and that partners pursue other goals in addition to just making a good decision, such as preserving the quality of their relationship. The following sections describe types of decisions, relationship structures, as well as interaction dynamics. After introducing a process model of purchasing decisions, we will conclude with a description of relevant research methods, particularly focusing on the Vienna Partner Diary.

1. Types of Decisions and Conflicts

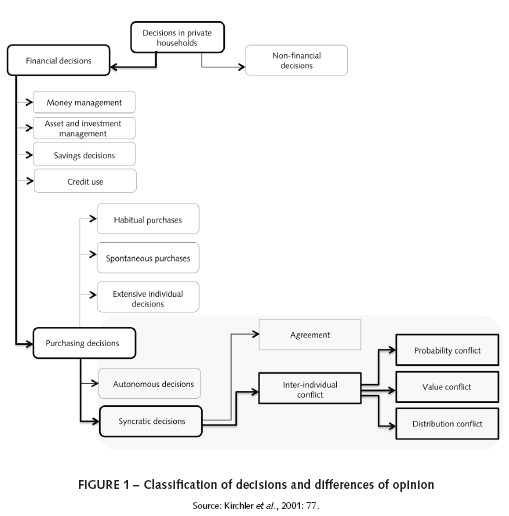

Decisions taken in the private household are either financial or not primarily financial (Ferber, 1973). Financial decisions relate to money management (budgeting out available funds, paying bills, etc.), decisions with respect to savings (deciding on what proportion of money is to be saved or spent), wealth and investment, the taking out of loans, and expenditures. Decisions of a non-financial nature regard issues such as employment and domestic work, those concerning the children, leisure-time activities, and the partners’ relationship to one another as well as other topics.

Detailed classifications of purchasing decisions can be found in the literature on spending activities in multi-person households (e.g. Lackman and Lanasa, 1993; Mottiar and Quinn, 2004). Classifications in marketing are typically based on the goods obtained through the purchase. Davis (1976) differentiates between purchasing decisions for frequently needed goods and services, long-lasting goods, and other economic decisions. Kotler (1982) focuses on the operating life of the goods and additionally refers to consumers’ shopping habits. He differentiates between non-durable goods, durable goods and services. Decisions about non-durable goods or goods for daily use are those regarding frequently bought items that are consumed shortly after purchase. Decisions about these goods usually proceed in an automatized way and their purchase is governed by routine. Expensive durable goods or goods used to satisfy sophisticated needs are acquired less frequently. Routines to govern these purchases rarely exist. More recently, it was suggested that a decision heuristic is used for low involvement purchases, but when involvement and social consequences increase, more advanced decision making tactics are used (James, 2015).

Oftentimes, long and complex decision-making processes are necessary to make a good choice and resolve differences of opinion between family members in a way that preserves the quality of the relationships involved.

The principal psychological characteristics of decision-making situations are (a) the availability of cognitive scripts to govern the decision-making process, (b) the financial resources committed to the purchase, (c) the social visibility of the good or service and (d) the degree to which various members of the household are affected (Kirchler et al., 2001). When products are bought frequently and the amount of information needed to make a satisfactory selection is low, partners dispose of cognitive scripts consisting of sequences of standard behaviors ready to use in a familiar situation, hence, automating the decision-making process. Purchases of expensive and socially visible goods typically do not involve scripts. Impulse-driven actions and habitual decisions are usually made by one person and proceed in an automatized way. Real decisions made by multiple individuals which may require decision-making processes that take place over a longer period of time often lead to the emergence of a disagreement or conflict. We define conflicts as more or less significant differences of opinion based on the fact that partners’ goals differ. The intensity of conflicts can range from minor differences in partners’ ideas to serious disputes about goals and values in which both partners find it essential to have their own way.

Retrospective reports underestimate the frequency of conflicts, as positive experiences are socially desirable. Given that conflicts may cause harm to a relationship, couples might prefer not to portray them as severe or as frequent as they actually occur when participating in surveys or interviews. Thus, on the one hand, research finds that differences of opinion are rare (e.g. McGonagle et al., 1992), for instance occurring 2-3 times per month. Similarly, in the Vienna Diary Study by Kirchler et al. (2001) only 2.5% of the recorded conversations between partners concerned conflicts. On the other hand, some research found regular differences of opinion (e.g. Gottman, 1994; Holmes, 1989; Surra and Longstreth, 1990). Conflicts also appear to be more prevalent among younger couples than older ones (Hinde, 1997). The literature on economic decision-making in private households assumes that most joint purchase decisions are preceded by differences of opinion but not necessarily severe conflicts (Spiro, 1983). Results of the Vienna Diary Study (Kirchler et al., 2001) showed that whereas couples spent less time discussing financial matters compared to others such as children and leisure time, the former most likely led to differences of opinion. In contrast, Papp et al. (2009) assert that conflicts do not primarily revolve around financial issues. However, financially driven conflicts are perceived to be more pervasive and pose greater difficulties on the path to being resolved, which subsequently results in a higher probability of procrastination.

Disagreements or differences of opinion are not always perceived as conflicts. Research by Klein and Milardo (1993) revealed that in 98% of cases where couples were asked about conflict situations, they made it seem as if there had been no conflict at all. When partners have mixed views, but are working towards the same goals, they do not tend to perceive their disagreement as a conflict. However, conflicts are recognized as such when partners’ goals diverge and value conflicts arise. It is also highlighted when partners make attempts to actively persuade one another in order to negotiate an advantage for themselves.

Brandstätter (1987) describes three types of conflicts. He defines differences of opinion with one unambiguously correct resolution as “probability conflicts” and those without any verifiably accurate solution as “value conflicts”. Within this second category, he also identifies “distribution conflicts”.

Probability conflicts occur when partners have the same goal but different views regarding advantages or disadvantages of a product. In such situations one cannot speak of a conflict in a negative way, since the couple discusses the issue matter-of-factly, trying to pinpoint the option that best fits their shared goal.

Value conflicts arise due to elementary differences in partners’ goals. For example, one partner has fundamental reservations with regard to the item. Value conflicts represent real conflict situations; thus, partners use various influence tactics in an attempt to persuade one another.

A distribution conflict relates to the allocation of costs and benefits. Even if both partners are convinced that a certain product is the best option, one partner might argue against the purchase as the good would primarily benefit the other person. In these situations partners usually try to find a solution by using their negotiation skills.

Decisions in private households can be classified according to the schema depicted in Figure 1. Importantly, conflictual decisions may contain elements of all three conflict types to a greater or lesser degree. Since decision-making is a process, one type of conflict might transform into another as the purchase is being discussed. For example, although spouses might have resolved a discussion about questions of values, this might not conclude the decision-making process. The couple might further negotiate over an asymmetrical distribution of benefits.

2. Relationship Structure and Interaction Dynamics

Couples in close relationships are dependent upon each other in their decisions and actions. They often tend to have an egalitarian structure as opposed to being characterized by a steep imbalance of power between partners. Peplau (1983) describes couples’ behavior patterns as not only characterized by strong mutual dependence of partners, but also as partners being uniquely interdependent.

The structure of close relationships can be described on the basis of two fundamental dimensions (Kirchler et al., 2001): emotional aspects of the relationship (relationship harmony) and hierarchical aspects (power and dominance structure). Decision-making processes proceed differently depending on the degree of “harmony” and “power” present in the relationship.

Relationship harmony can be described with terms such as love, empathy, satisfaction, relationship quality and cohesion. Harmony is tightly linked to relationship stability which is in turn dependent on commitment (ibidem). Couples in harmonious relationships develop different interaction dynamics than unhappy couples. While relationships with decreasing quality tend to resemble a business relation, happy couples seek to realize their joint wishes taking the goals of both partners into consideration (Holmes, 1981).

In addition to the emotional characteristics of a romantic relationship, the balance of power between partners plays an important role in decision-making situations. Every couple establishes individual relationship norms which might reserve decisions about certain product categories to one partner, independently of their power status (Simpson et al., 2012). In harmonious relationships it is presumed that power does not vary much between spouses or at least that the more powerful partner does not use their advantage to exploit the other person in decision-making situations. In disharmonious relationships, on the other hand, it can be assumed that the more powerful partner makes use of their superior role. Furthermore, the dominant spouse is expected to prevail in situations, where the outcome of the decision is especially important to them (ibidem).

Social exchange theory (Nye, 1979) is based on the assumption that relationships function according to the economic principle of reciprocal giving and receiving. Even happy couples are assumed to keep a mental account of resources exchanged and only remain in a relationship when they gain benefits from it. Simpson et al. (2012) also stress the importance of partners’ perceived interdependence according to Kelley and Thibaut’s (1978) interdependence theory. The more a person gains from their partner (e.g. status, money, affection) the more dependent they become and, therefore, try to correspond to the desires of the significant other. Couples in harmonious relationships act according to the so-called “love principle” (Kirchler et al., 2001). As the emotional bond between partners weakens, this love principle begins to mutate into a “credit principle”. In this case, spouses still seek to do each other favors and are considerate of one another, however, they expect their efforts to be repaid later, similar to a form of long-term credit. If the quality of the relationship declines even further, interactions correspond to the “equity principle”, where the couple starts to act more and more like business partners. While power relations are relatively insignificant among happy couples, in relationships that have cooled, the more powerful person takes advantage of their position, using it to control the rules of exchange entirely. Relationships of these kinds can be defined to act according to a “self-interest principle”.

3. Decision-making Processes

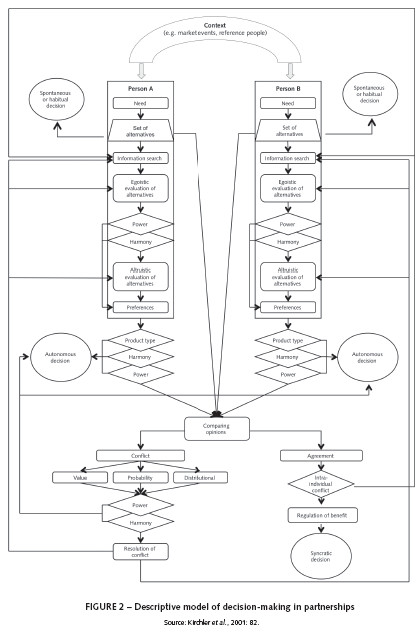

The following section presents a descriptive process model for economic decision-making between two people in a close relationship (see Figure 2) which was developed by Kirchler et al. (2001). Decisions start with a certain desire for a good on the part of one or both partners. The first step towards satisfying this need is to gather information about the available alternatives. However, a desire can also be fulfilled immediately without gathering information (spontaneous decision) or purchases can be made according to established routines (habitual decision). It all depends on whether realizing a given desire would generate high or low costs, whether the purchase is followed by socially visible consequences resulting in short- or long-term changes, as well as whether one or more individuals are affected.

The appearance of infrequent desires typically leads to a real decision-making process. The active partner – that is, the one harboring the desire – can either inform their spouse about a product wish right away, gather information about options on their own in order to share their plans afterwards or make an autonomous decision. In contrast to individual decisions, autonomous decisions do not proceed entirely independently of the passive partner’s preferences and goals. The active partner estimates the benefits of the decision for the other person, as well as their likelihood of agreeing to the action, and takes these factors into account. In their dyadic framework Simpson et al. (2012) postulate that spouses influence each other in three distinct ways when deciding for a specific product option. Firstly, a person’s preference for a specific product might be influenced by their partner’s beliefs and attitudes. Secondly, even if the active partner has already formed a preference for a certain option, considering the other person’s beliefs and attitudes about that option might lead to an alternative final decision. The third influence type refers to the alignment of partners’ beliefs and attitudes over time, due to continuous interaction processes which make them more similar.

Whether a spontaneous, habitual, autonomous or joint decision is made will depend upon the type of decision, as well as the partners’ relationship with one another. When options are simple, inexpensive, banal and do not attract a great deal of social attention, the chances of joint decision-making are low. Similarly, spouses are unlikely to make a joint decision when the active partner occupies the more powerful position in a relationship with decreasing quality or when couples in more traditional relationships exhibit strict role segmentations, matching decisions to partners’ spheres of control.

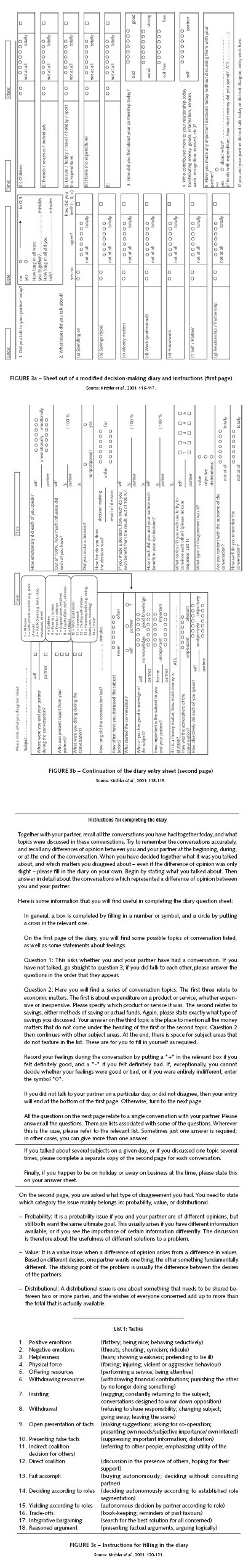

Joint decision-making either starts at the desire phase, the information-gathering phase or the selection phase. After one or both partners have gathered information about possible options and have evaluated them, the options are assessed as to whether they satisfy the present desire and a selection is made. In this phase partners’ differing interests or levels of information might lead to a conflict. Depending on the type of conflict spouses might use one of 18 influence tactics (Kirchler, 1989; see Figure 3c). Research found that couples typically prefer reasoning tactics, bargaining strategies or the open presentation of facts to persuade their spouses (Kirchler, 1993a; Kirchler et al., 1999). The tactics used depend upon the type of conflict and the quality of the couple’s relationship. Kirchler (1993a) argues that the use of tactics based on reason is more prevalent in probability conflicts, where partners agree on the goal, but are at odds over the means to achieve it. Ward (2005) shows that conflicts about products from different product categories (distribution conflicts) elicit significantly greater use of influence tactics, compared with decisions including more similar products. Kirchler (1993a) reports that happy couples primarily use integrative bargaining tactics, positive emotions, as well as the open presentation of facts. Also, partners who feel close to their spouses more often use references to the romantic relationship in order to persuade their counterparts in a dispute (Oriña et al., 2002). Further differences in the use of persuasive tactics are due to the partners’ gender, as well as the differing product categories involved. Bokek-Cohen (2008) analyzed the use of a persuasive tactic called “triangulation”, where partners use third parties to convince their mates. Results show a higher usage frequency of this strategy in men. Whereas men use the tactic more frequently with respect to vacation decisions, women triangulate the most with respect to housing options. Research by Kirchler et al. (1999) shows that conflicts about economic or financial issues primarily lead to reasoning tactics, as well as to the open display of facts.

Next, it needs to be determined whether implementing the decision will cause any asymmetries in influence and benefits. If one partner dominated decision-making, they have incurred an influence debt and thus face pressure to give in to their spouse in an upcoming decision-making situation. All influence and utility debts are kept track of in a mental account. It can be assumed that whether spouses grant their partner a “loan” or insist on settling asymmetries right away depends on the couple’s interactions governed by the love, credit, self-interest, or equity principle.

After a final agreement on whether the distribution of benefits was asymmetrical or not and how this should be dealt with, the decision-making process comes to an end (Pollay, 1968).

4. Methods for Studying Decision-making

In the study of joint decision-making processes in private households, obtaining information from both partners presents something of a barrier. Although the development of online survey techniques has facilitated the research process, researchers still face difficulties in gathering sufficient sample sizes due to incomplete data from partners. Gathering observational data through individuals’ social media websites, such as Facebook, or their purchase histories is not suited to study interaction processes between spouses; in addition, it raises questions on the ethical issues of invasion of privacy (Simpson et al., 2012).

Decision-making processes can be either observed in their natural settings or in the laboratory. Although observational laboratory methods enable the investigation of participants’ unconscious or non-verbal reactions in purchasing interaction processes (Grønhøj and Bech-Larsen, 2010), it is difficult to persuade spouses to come into the laboratory in order to fight over the allocation of an imaginary budget. Observing couples in their natural settings constitutes the problem of higher costs due to expenditure of time (ibidem) and participants might react to observer presence, which results in a tendency to keep interactions superficial. Lee and Beatty (2002) try to overcome this problem by videotaping families in their own home while discussing a simulated purchasing decision problem. In assessing the relative influence of each family member on the decision outcome by using verbal and non-verbal cues the authors report high reliability coefficients. In similar studies (e.g. Campbell et al., 2005; Oriña et al., 2002) participating couples were asked to rewarm a recent dispute they had not been able to resolve yet. In order to minimize undesired effects of the laboratory setting participants’ behavior was videotaped, instead of being directly observed by the researchers. Ward (2005) used questionnaires to assess partners’ individual future purchasing preferences for certain products. In a next step, couples were asked to discuss several product choices which had been specifically arranged to display conflicting interests between partners. The task was rated as realistic and was perceived to be less artificial than conventional laboratory studies.

Interviews and surveys entail different methodological challenges. When partners are asked to describe their joint experiences, their reports frequently do not match. These discrepancies are partially rooted in the difficulties people have in recalling banal events, as well as in people’s tendency to distort their accounts in a self-serving way (e.g. De Dreu et al., 1995; Smith et al., 1999). Kleppe and Gronhaug (2003) conducted in-depth interviews on the spouses’ major decisions in their first years of marriage, with both partners present. The couples’ reactions were positive and they seemed open-minded even when addressing sensitive topics. More importantly, spouses corrected each other in their descriptions of past decision-making processes, implying that distorted results due to recall bias might be less likely using this research approach. Grønhøj and Bech-Larsen (2010) stress the effectiveness of using vignette methods (brief descriptions of situations) to complement conventional qualitative approaches. With this method, reactions to detailed, clearly defined situations can be elicited so that results can be more easily compared across participants. Also, the stories function as a “collective prime”, which helps participants to remember past purchasing interaction processes more accurately.

With regard to household surveys, aspects to be considered are: who is most suitable to respond, what experiences are to be reported and how reliably respondents will be able to provide answers. Husbands’ and wives’ statements about purchasing a car or furniture are quite similar when averaged across an entire sample (Davis, 1970). When viewed on the individual couple level, however, spouses’ statements differ significantly from one another. Kirchler (1989) summarized the results of 16 studies in which spouses reported on influence patterns in their relationship, finding that these accounts were around 60% in agreement with one another.

Taken together, neither observational techniques nor surveys seem to be suitable means of collecting data about everyday life in private households (Kirchler et al., 2001; Penz and Kirchler, 2016). By using a diary approach, problems related to ecological validity, memory distortions or mood biases can be reduced. Diaries enable researchers to record experiences as they occur, hence it becomes possible to study processes rather than simply collect data on past events. Moreover, they increase the reliability of reports, since the constant recording of ordinary experiences encourages participants to pay more attention to them (Rehn, 1981). Also, the accuracy of prognoses is expected to rise when aggregate data from several recording points is used (Epstein, 1986).

4.1. Diaries

Diaries have been typically used at the level of the individual. Brandstätter (1977) constructed a time-sampling diary to investigate everyday moods. At random intervals over a longer period of time study participants were asked to record their current mood, state possible reasons for it and provide descriptions of where they were, what they were doing and who they were with. When research is focused on a specific topic, such as purchasing decisions, the diary needs to be filled in whenever the topic under investigation comes up (event diaries). This is necessary to collect a sufficiently large number of relevant events. It is important to clearly define the event of interest, since participants might otherwise fail to identify the occurrence of the topic.

Also, researchers should consider different diary techniques (Bolger et al., 2003). Information can be gathered through a paper-and-pencil diary which represents the easiest and most commonly used method. Some limitations are that participants fail to fill in information at scheduled times and later try to reconstruct past events or experiences. This also raises compliance issues, since researchers have trouble in verifying whether participants have filled in their responses on time. Augmented diaries which use paper-and-pencil questionnaires in combination with signaling devices (e.g. pagers) or phone call reminders (e.g. Almeida, 2005) try to overcome the problem of honest forgetfulness (Carstensen et al., 2011). However, in addition to being more costly this method runs the risk of disrupting participants in their daily routines, hence they might deliberately refuse to use those devices (Bolger et al., 2003). Newer developments in electronic data collection methods enable the use of handheld computers with customized questionnaire programs, also known as Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) (Laurenceau and Bolger, 2005). Software programs available for free use include Barrett and Feldman Barrett’s (2000) Experience Sampling Program (ESP). This technology allows researchers to identify incompliant participants by time stamping their answers. Also, it enables them to randomize the order of questions to avoid habituation effects, as well as to use signaling which is attuned to a person’s individual schedule. Importantly, electronic data collection methods facilitate the data entry process. While these methods have the potential to revolutionalize conventional paper-and-pencil diary techniques (Axinn and Pearce, 2006), researches should keep in mind the need to provide participants with proper training to overcome computer illiteracy. Lately, researchers have developed smartphone apps programmed to function as diaries (Miller, 2012). Examples constitute studies assessing participants’ day-to-day thoughts and feelings (Killingsworth and Gilbert, 2010), as well as students’ time spent during a semester (Runyan et al., 2013). Although the programming of so-called “Psych Apps” is still in an early stage, smartphones have opened up valuable opportunities for researchers, due to their handy size and familiarity, as well as their constantly improving processor quality and memory storage (Miller, 2012).

Time-sampling diaries and event diaries have many advantages over other methods, which justifies the greater effort and expense involved. The phenomenon under investigation is studied as it actually occurs, which prevents errors of memory. Moreover, the diary is independently “administered” by study participants themselves, hence privacy is respected. Intimate situations are not disturbed by the presence of invasive outsiders so there is little pressure to make a good impression. Events are not ripped from their typical contexts in order to study them, but rather remain embedded in the stream of everyday life, thus maximizing ecological validity (e.g. Almeida, 2005; Hektner et al., 2007; Laurenceau and Bolger, 2005; Shiffman et al., 2008). Respondents’ contact with other people as well as activities outside the private sphere can be recorded. Bolger et al. (2003) recommend using the diary approach to reliably measure changes in variables over time. Although fluctuations over time might be investigated with traditional longitudinal studies, assessments are typically undertaken at long time intervals, leading to less accurate results. In addition to that, the authors stress the unique opportunity in investigating the triggers of the mental states or behaviors involved, as well as their correlates and consequences.

Diaries have been employed in household studies in order to capture how couples use their time (Hornik, 1982; Vanek, 1974; Robinson et al., 1977). Larson and Bradney (1988), as well as Carstensen et al. (2011) collected data on people’s moods in the presence of friends and family. Almeida (2005), Almeida and Kessler (1998), Almeida et al. (1999), and Bolger and colleagues (Bolger et al., 1989a, 1989b) investigated experiences of stress in everyday life and the spillover effects of work stress on relationships. Laireiter et al. (1997) analyzed social networks by means of diaries. Even couples’ interaction processes have been successfully studied using diaries (Auhagen, 1987, 1991; Brandstätter and Wagner, 1994; Campbell et al., 2005; Duck, 1991; Feger and Auhagen, 1987; Papp et al., 2009).

Hinde (1997) notes that diaries are viable instruments for studying intimate relationships. Particularly when both partners are required to complete them, the fact that the couple represents a single entity is taken into account. Processes can be investigated collecting multiple entries per day over a longer period of time.

As Stone et al. (1991) note, this need for a longer data collection period frequently comes at the expense of sample size. Nevertheless, this disadvantage needs to be accepted if detailed information of events that typically remain unnoticed in daily life is required. Bolger et al. (2003) stress the importance of future research to investigate the effect of the diary completion process on participants’ experiences and behaviors. In this regard, filling in a diary several times a day might lead to effects of reactance. Also, habituation effects are possible in that participants might develop routine answers which might not correspond to their actual feelings or thoughts. However, this can be countered by using electronic diaries which allow researchers to randomize questions.

4.2. Vienna Diary Study

In the Vienna Diary Study (Kirchler et al., 2001) an event diary, designed by Kirchler (1995), was applied to collect information on couples’ decision-making over a longer period of time. Figures 3a, 3b and 3c show the diary sheets participants reported on every evening. When completing the diary they note whether or not they spoke to one another that day, how long the conversation lasted, what they talked about, whether or not a difference of opinion arose and how they felt during the conversation. They also describe how good their relationship is, as well as how free and strong they feel in the relationship at present. On days in which differences of opinion arise, they also note what the conflict was about, where they were during the conversation, what they were doing and who else was present. The term conflict includes differences of opinion with varying degrees of severity, opposing interests, disputes over facts, as well as divergent beliefs with respect to various topics (cf. Hinde, 1997: 154). Couples also note how long the conversation lasted; how often they had already discussed the topic; who started the conversation; which partner was more knowledgeable about the topic; how important the topic was to the couple; how emotional or matter-of-fact the conversation was; how much influence each person had on the outcome of the conversation; whether or not a decision was made; how high each partner’s subjective benefit was; which persuasive tactics were used; whether the conflict was primarily factual, a value conflict, or a conflict of distribution; and how satisfied they were with the outcome of the conversation. When the difference of opinion is related to economic issues, the partners also estimate the amount of money at stake. At the beginning and end of the diary-writing period, partners additionally filled in surveys about relationship satisfaction and dominance structures. Also, they completed a personality questionnaire and data about their experiences with filling in the diary was collected.

4.3. Procedure and Experiences with the Vienna Diary Study

Couples were recruited by the use of various strategies. In total 46 couples decided to participate in the Vienna Diary Study. In the beginning they were informed about the study, its goals and how to fill in the diaries and surveys. Each couple was provided with a personal advisor. It was the advisor’s role to stay in regular contact with the couples, answer questions and encourage them to remain motivated throughout the study. Apart from that, meetings were organized in which initial results from the first surveys were presented and experts gave lectures on topics determined in consultation with the couples. Finally, financial compensation was intended to act as an incentive for participants to complete the study.

The official period of diary entries started after a two-day habituation phase. Each couple received a diary consisting of a set of diary sheets (Figures 3a, 3b and 3c). Completing them took just a few minutes every evening. In order to ensure that diary entries remained confidential, each partner received a separate paper box with a small opening (similar to a “safe”) through which they were supposed to insert the forms.

Surveys regarding relationship harmony, power dynamics, gender role orientation and personality were completed at the beginning and end of the data collection period. Apart from that, a questionnaire on the tactics employed in different conflict types (Kirchler, 1993a; 1993b) was provided and participants were to complete a survey measuring the distribution of influence in various economic and non-economic decision-making situations, referring to a former study by Davis and Rigaux (1974).

Overall, experiences with the diary were positive. At the end of the data collection period, participants were asked to rate the intelligibility and ease of answering the diary items, as well as their motivation to complete the diary on a daily basis. Both the intelligibility of an instrument and the ease with which items can be answered are an indicator of its quality. On the other hand, if questions are too hard to answer, it can be assumed that people will tend to give random answers, hence data quality decreases.

In the first part of the post-questionnaire, participants indicated how difficult it had been for them to answer the questions from the diary sheets. Most respondents gave ratings below an intermediate level of difficulty. Questions about the amount of influence wielded by each partner in decision-making, the benefits each would gain from a given decision and benefits accrued in previous decisions seemed to be more difficult for participants to answer. This might be due to the fact that questions of distribution are not considered to be part of intimate relationships.

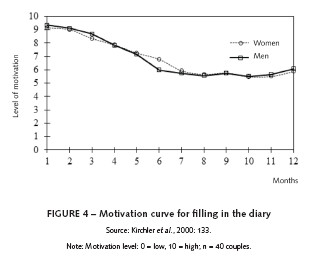

Participants were also asked to retrospectively indicate how high their level of motivation in filling in the diary was during each month of the data collection period. While motivation was high at the beginning of the data collection period, it sank throughout the first half of the year and then held steady at its lower level. Figure 4 depicts levels of motivation for men and women.

In addition to the retrospective collection of data on motivation through the post-questionnaire, participants’ motivation was also extrapolated from the diary data itself. Kirchler et al. (2001) investigated whether systematic trends could be observed in the diligence with which the diary entries were filled in over the data collection period. The number of missing entries was determined using the general items about relationship quality which were supposed to be filled in every day. In the initial analysis, it was investigated whether differences could be observed between the first and second halves of the data collection period. The total number of missing entries was quite low. The maximum missing value rate was 4.83%, with a range of 2.42 to 4.83%. Fewer missing entries were observed in the second half of the year, with an average of 4.32 versus 2.87% for the first and second halves of the year, respectively. This means that participants became more diligent in completing the diary over time.

The post-questionnaire also asked participants to comment on the data collection process itself. Information was collected on whether the diaries had always been filled in properly, whether participants’ answers were honest, and how much of a burden it had been to complete the diary. Participants’ responses were generally very positive.

Finally, reliability and validity scores were calculated. Different analyses showed that the diary exhibited quite satisfactory results with regard to reliability, validity and stability of data.

In conclusion, we would like to emphasize that the method employed in the Vienna Diary Study appears to be a useful tool for collecting data on the complex interaction processes in private households of couples. Participants’ subjective experiences with the diary were positive and valuable information was gained with regard to important research topics, such as financial disagreements and conflict resolution. Also, reliability and validity scores were sufficiently high to make the claim that the findings reported in Kirchler et al. (2001) provide a reliable picture of the everyday lives of the couples who participated in the study.

Conclusion

The present paper introduced research on joint purchase decisions within households. Determinants of decision processes are described: we argue that decision processes depend on the type of purchase decision as well as the structure of partners’ relationship. This is particularly relevant for marketing, as it helps to better understand who decides what to buy in purchasing decisions and how decision processes evolve and to develop marketing strategies accordingly.

The focus of the article relies on research methods applied in psychology, sociology and marketing to study decision processes in close relationships. We juxtapose studies discussing advantages and disadvantages of observational techniques, laboratory studies, surveys and diary techniques. Since purchasing decisions in private households are mundane events embedded in multifold daily activities, partners encounter difficulties to reliably recall their decision dynamics and to report them accurately in questionnaire studies. Observations of decisions in the laboratory, on the other hand, lack ecological validity, especially when couples are asked to fight over an artificial disagreement or conflict.

We conclude that diary methods in general and the Vienna Partner Diary in particular overcome difficulties encountered in laboratory and survey studies. However, diary studies require highly committed participants and usually involve small sample sizes. Therefore, diaries are useful to acquire new insights into decision dynamics. Results shall be used to design survey studies which are conducted on representative samples in order to confirm or disconfirm the outcome of diary studies and to allow for a generalization of findings.

REFERÊNCIAS

Almeida, David M. (2005), “Resilience and Vulnerability to Daily Stressors Assessed via Diary Methods”, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(2), 64-68.

Almeida, David M.; Kessler, R. C. (1998), “Everyday Stressors and Gender Differences in Daily Distress”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 670-680.

Almeida, David M.; Wethington, E.; Chandler, A. L. (1999), “Daily Transmission of Tensions between Marital Dyads and Parent-child Dyads”, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(1), 49-61.

Auhagen, A. E. (1987), “A New Approach for the Study of Personal Relationships: The Double Diary Approach”, The German Journal of Psychology, 11(1), 3-7.

Auhagen, A. E. (1991), Freundschaft im Alltag. Eine Untersuchung mit dem Doppeltagebuch. Bern: Huber. [ Links ]

Axinn, W. G.; Pearce, L. D. (2006), Mixed Method Data Collection Strategies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Barrett, D. J.; Feldman Barrett, L. (2000), ESP: The Experience Sampling Program [Computer software and manual]. Accessed on 14.09.2016, at http://www.experience-sampling.org/.

Bokek-Cohen, Y. A. (2008), “Tell her she’s Wrong: Triangulation as a Spousal Influence Strategy”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(4), 223-229.

Bolger, N.; Davis, A.; Rafaeli, E. (2003), “Diary Methods: Capturing Life as it is Lived”, Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 579-616.

Bolger, N.; DeLongis, A.; Kessler, R. C.; Schilling, E. A. (1989a), “Effects of Daily Stress on Negative Mood, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 808-818.

Bolger, N.; DeLongis, A.; Kessler, R. C.; Wethington, E. (1989b), “The Contagion of Stress across Multiple Roles”, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51(1), 175-183.

Brandstätter, H. (1977), “Wohlbefinden und Unbehagen”, in W. H. Tack (ed.), Bericht über den 30. Kongreß der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Psychologie in Regensburg1976, vol. 2. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe, 60-62.

Brandstätter, H. (1987), “Gruppenleistung und Gruppenentscheidung”, in D. Frey and S. Greif (eds.), Sozialpsychologie. Ein Handbuch in Schlüsselbegriffen. München, Germany: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 182-186.

Brandstätter, H., Wagner, W. (1994), “Erwerbsarbeit der Frau und Alltagsbefinden von Ehepartnern im Zeitverlauf”, Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 25, 126-146.

Campbell, L.; Simpson, J. A.; Boldry, J.; Kashy, D. A. (2005), “Perceptions of Conflict and Support in Romantic Relationships: The Role of Attachment Anxiety”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 510-531.

Carstensen, L. L.; Turan, B.; Scheibe, S.; Ram, N.; Ersner-Hershfield, H.; Samanez-Larkin, G. R.; Nesselroade, J. R. (2011), “Emotional Experience Improves with Age: Evidence based on over 10 Years of Experience Sampling”, Psychology and Aging, 26(1), 21-33.

Davis, H. L. (1970), “Dimensions of Marital Roles in Consumer Decision Making”, Journal of Marketing Research, 7(2), 168-177.

Davis, H. L. (1976), “Decision Making within the Household”, Journal of Consumer Research, 2(4), 241-260.

Davis, H. L.; Rigaux, B. P. (1974), “Perception of Marital Roles in Decision Processes”, Journal of Consumer Research, 1(1), 51-62.

De Dreu, C. K. W.; Nauta, A.; Van de Vliert, E. (1995), “Self-Serving Evaluations of Conflict Behavior and Escalation of the Dispute”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(23), 2049-2066.

Duck, S. W. (1991), “Diaries and Logs”, in B. M. Montgomery and S. W. Duck (eds.), Studying Interpersonal Interaction. New York, NY: Guilford, 141-161.

Epstein, S. (1986), “Does Aggregation Produce Spuriously High Estimates of Behavior Stability?”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(6), 1199-1210.

Feger, H.; Auhagen, A. E. (1987), “Unterstützende soziale Netzwerke: Sozialpsychologische Perspektiven”, Zeitschrift für klinische Psychologie, 16(4), 353-367.

Ferber, R. (1973), “Family Decision Making and Economic Behavior”, in E. Sheldon (ed.), Family Economic Behavior. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 29-61.

Grønhøj, A.; Bech‐Larsen, T. (2010), “Using Vignettes to Study Family Consumption Processes”, Psychology & Marketing, 27(5), 445-464.

Gottman, J. M. (1994), What Predicts Divorce? The Relationship between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Hektner, J. M.; Schmidt, J. A.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2007), Experience Sampling Method: Measuring the Quality of Everyday Life. London, UK: Sage. [ Links ]

Hinde, R. A. (1997), Relationships. A Dialectical Perspective. Hove, UK: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Holmes, J. G. (1981), “The Exchange Process in Close Relationships”, in M. D. Lerner and S. G. Lerner (eds.), The Justice Motive in Social Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum, 261-284.

Holmes, J. G. (1989), “Trust and the Appraisal Process in Close Relationships”, in W. H. Jones and D. Perlman (eds.), Advances in Personal Relationships, vol. 2. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley, 57-104.

Hornik, J. (1982), “Situational Effects on the Consumption of Time”, Journal of Marketing, 46(4), 44-55.

James, K. (2015), “A Review and Update of the Classification of Goods System: A Customer Involvement System”, Proceedings of the 2009 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 67-67.

Kelley, H. H.; Thibaut, J. W. (1978), Interpersonal Relationships: A Theory of Interdependence. New York, NY: Wiley. [ Links ]

Killingsworth, M. A.; Gilbert, D. T. (2010), “A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind”, Science, 330(6006), 932-932.

Kirchler, E. (1989), Kaufentscheidungen im privaten Haushalt. Eine sozialpsychologische Analyse des Familienalltages. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe. [ Links ]

Kirchler, E. (1993a), “Beeinflussungstaktiken von Eheleuten: Entwicklung und Erprobung eines Instrumentes zur Erfassung der Anwendungshäufigkeit verschiedener Beeinflussungstaktiken in familiären Kaufentscheidungen”, Zeitschrift für experimentelle und angewandte Psychologie, 40(1), 103-132.

Kirchler, E. (1993b), “Spouses’ Joint Purchase Decisions: Determinants of Influence Strategies to Muddle through the Process”, Journal of Economic Psychology, 14(2), 405-438.

Kirchler, E. (1995), “Studying Economic Decisions within Private Households: A Critical Review and Design for a Couple Experiences Diary”, Journal of Economic Psychology, 16(3), 393-419.

Kirchler, E.; Rodler, C.; Hoelzl, E.; Meier, K. (1999), “Entscheidungen von 40 Paaren während eines Jahres. Die Wiener-Tagebuchstudie”, Unpublished Research Paper. Wien, Austria: Universität Wien.

Kirchler, E.; Rodler, C.; Hoelzl, E.; Meier, K. (2000), Liebe, Geld und Alltag: Entscheidungen in engen Beziehungen. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe. [ Links ]

Kirchler, E.; Rodler, C.; Hoelzl, E.; Meier, K. (2001), Conflict and Decision Making in Close Relationships: Love, Money and Daily Routines. Hove, UK: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Klein, R.; Milardo, R. M. (1993), “Third-party Influence on the Management of Personal Relationships”, in S. Duck (ed.), Social Context and Relationships. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 55-77.

Kleppe, I. A.; Gronhaug, K. (2003), “No Consumer is an Island. The Relevance of Family Dynamics for Consumer Welfare”, Advances in Consumer Research, 30, 314-321.

Kotler, P. (1982), Marketing-Management. Analyse, Planung und Kontrolle. Stuttgart, Germany: Poeschel. [ Links ]

Lackman, C.; Lanasa, J. M. (1993), “Family Decision-making Theory: An Overview and Assessment”, Psychology & Marketing, 10(2), 81-93.

Laireiter, A. R.; Baumann, U.; Reisenzein, E.; Untner, A. (1997), “A Diary Method for the Assessment of Interactive Social Networks: The Interval-contingent Diary SONET-T”, Swiss Journal of Psychology, 56(4), 217-238.

Larson, R. W.; Bradney, N. (1988), “Precious Moments with Family Members and Friends”, in R. M. Milardo (ed.), Families and Social Networks. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 106-126.

Laurenceau, J. P.; Bolger, N. (2005), “Using Diary Methods to Study Marital and Family Processes”, Journal of Family Psychology, 19(1), 86-97.

Lee, C. K.; Beatty, S. E. (2002), “Family Structure and Influence in Family Decision Making”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19(1), 24-41.

McGonagle, K. A.; Kessler, R. C.; Schilling, E. A. (1992), “The Frequency and Determinants of Marital Disagreements in a Community Sample”, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9(4), 507-524.

Miller, G. (2012), “The Smartphone Psychology Manifesto”, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(3), 221-237.

Mottiar, Z.; Quinn, D. (2004), “Couple Dynamics in Household Tourism Decision Making: Women as the Gatekeepers?”, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10(2), 149-160.

Nye, F. I. (1979), “Choice, Exchange, and the Family”, in W. R. Burr; R. Hill; F. I. Nye; and I. L. Reiss (eds.), Contemporary Theories about the Family, vol. 2. New York, NY: Free Press, 1-43.

Oriña, M. M.; Wood, W.; Simpson, J. A. (2002), “Strategies of Influence in Close Relationships”, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(5), 459-472.

Papp, L. M.; Cummings, E. M.; Goeke‐Morey, M. C. (2009), “For Richer, for Poorer: Money as a Topic of Marital Conflict in the Home”, Family Relations, 58(1), 91-103.

Penz, E.; Kirchler, E. (2016), “Households in International Marketing Research: Vienna Diary Technique (VDT) as a Method to investigate Decision Dynamics”, International Marketing Review, 33(3), 432-453.

Peplau, L. A. (1983), “Roles and Gender”, in H. H. Kelley; E. Berscheid; A. Christensen; J. H. Harvey; T. L. Huston; G. Levinger; E. McClintock; L. A. Peplau; D. R. Peterson (eds.), Close Relationships. New York, NY: Freeman, 220-264.

Pollay, R. W. (1968), “A Model of Family Decision Making”, British Journal of Marketing, 2, 206-216.

Rehn, M. L. (1981), Die Theorie der objektiven Selbstaufmerksamkeit und ihre Anwendung auf eine neue Methode der Befindensmessung: Das Tagebuch (Unpublished diploma thesis). Erlangen: Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg.

Robinson, J. P.; Yerby, P.; Fieweger, J.; Somerick, N. (1977), “Sex-Role Differences in Time Use”, Sex Roles, 3(5), 443-458.

Runyan, J. D.; Steenbergh, T. A.; Bainbridge, C.; Daugherty, D. A.; Oke, L.; Fry, B. N. (2013), “A Smartphone Ecological Momentary Assessment/Intervention ‘App’ for Collecting Real-time Data and Promoting Self-awareness”, PLoS One, 8(8). Accessed on 14.09.2016, at http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0071325.

Shiffman, S.; Stone, A. A.; Hufford, M. R. (2008), “Ecological Momentary Assessment”, Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1-32.

Simpson, J. A.; Griskevicius, V.; Rothman, A. J. (2012), “Consumer Decisions in Relationships”, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(3), 304-314.

Smith, R. E.; Leffingwell, T. R.; Ptacek, J. T. (1999); “Can People Remember how they Coped? Factors Associated with Discordance between Same-day and Retrospective Reports”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(6), 1050-1061.

Spiro, R. L. (1983), “Persuasion in Family Decision-making”, Journal of Consumer Research, 9(4), 393-402.

Stone, A. A.; Kessler, R. C.; Haythornthwaite, J. A. (1991), “Measuring Daily Events and Experiences: Decisions for the Researcher”, Journal of Personality, 59(3), 575-607.

Surra, C. A.; Longstreth, M. (1990), “Similarity of Outcomes, Interdependence, and Conflict in Dating Relationships”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(3), 501-516.

Vanek, J. (1974), “Time Spent in Housework”, Scientific American, 231, 116-120.

Ward, C. B. (2005), “A Spousal Joint Decision Making Exercise: Do Couples Perceive Differences in Influence Tactics Used in Decisions Involving Differing Product Categories and Levels of Product Disagreement?”, Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 21(2), 9-22.

Received on 01.02.2016

Accepted for publication on 11.05.2016

NOTAS

* Parts of the present article have been taken from and overlap with the content of Kirchler, Rodler, Hoelzl, and Meier (2001), Conflict and Decision Making in Close Relationships: Love, Money and Daily Routines. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.