Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social n.197 Lisboa 2010

The challenges of urban renewal. Ten lessons from the catalan experience

Oriol Nel·lo*

* Department of Geography, Universidad Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra 08193, Barcelona, Spain. e-mail: oriol.nello@gencat.cat

Catalonia has a long history of local level urban renewal. With the approval of the Law on neighbourhoods requiring special attention, considerable efforts have been made in order to extend these experiences to both metropolitan and regional spheres. Such commitment has led to the implementation of comprehensive renewal programmes in 117 neighbourhoods. The article analyses the objectives, results, and drawbacks of this urban policy, focusing especially on inter-administrative relations and multilevel governance. The text reflects upon the following aspects: the transversal vision on urban renewal; the selection process; the comprehensive nature of actions performed; the role of public investment; the relationship between regional and local administrations; the potentialities and challenges of shared financing; local community involvement; capitalisation of experiences; evaluation of results; adaptation to change.

Keywords: urban renewal; institutional governance; Catalonia.

Os desafios da regeneração urbana. Dez lições da experiência catalã

A Catalunha tem uma longa história de regeneração urbana local. Com a aprovação da Lei de bairros que necessitam de atenção especial, têm sido feitos consideráveis esforços no sentido de alargar estas experiências para as escalas metropolitana e regional. Este compromisso levou à implementação de programas de regeneração urbana em 117 bairros. O artigo analisa os objectivos, resultados e dificuldades desta política, focando as relações inter-administrativas e de governança multi-escalar. Aborda, em particular, os seguintes aspectos: a visão transversal em torno da regeneração urbana; o processo de selecção; a natureza das acções e investimentos; o papel do investimento público; a relação entre as administrações regional e local; as potencialidades e desafios do financiamento partilhado; o envolvimento das comunidades locais; a capitalização de experiências; a avaliação de resultados, e a adaptação à mudança.

Palavras-chave: regeneração urbana; governança institucional; Catalunha.

In 2004, the Parliament of Catalonia approved the Law of improvement of neighbourhoods, urban areas and small towns requiring special attention1. This regulatory framework, which bears some singularities whether at the Iberian or the European levels, seeks to foster comprehensive renewal projects in those neighbourhoods experiencing the greatest urban deficits and where, as a result, populations needing social assistance tend to concentrate. In the subsequent six years, comprehensive interventions took place in 117 neighbourhoods inhabited by over 900,000 people (12% of the Catalan population) and investment amounting to 1,2 billion was allocated, funded equally by both the regional government (Generalitat) and the respective municipalities (Figure 1).

Territorial distribution of the programme (2004-2009)

[figure 1]

The application of this programme has brought to light some of the recurrent challenges to urban renewal processes: complexity in the physical intervention, financing problems, the need to comprehensively intervene, difficulties in achieving cooperation between different administrative levels, active involvement of neighbourhood residents, and so forth. These challenges were met using tools we may classify as relatively innovative. Hence, the application of the Law on neighbourhoods constitutes, in our opinion, an important case when studying the governance challenges posed within the context of urban transformation in Europe.

This text therefore provides an overview on this practical experience in order to reach broader conclusions2. As stated, these conclusions have been articulated in ten proposals, lessons disciplinary, administrative, and political to be drawn from this experience. The structure of the article responds to these ten proposals, devoting a section to analyse each one.

A last warning before we begin. In this article, we adopt the word urban renewal (rehabilitación urbana, in Spanish), a wording we prefer, instead of the concept regeneration, as the latter is pervaded with organicist and even moral meanings. In Spanish, the term rehabilitación has two meanings in the dictionary. The first to return to its former state would be inadequate for these purposes given that many of the neighbourhoods covered have experienced serious inefficiencies right from the moment they were built. On the other hand, the second meaning to re-establish its own rights. incorporates exactly the objective of that which, in our opinion, urban policies have to strive to achieve: to re-establish rights for all citizens irrespective of just where they live. Hence, it is in this sense that we subsequently employ renewal.

The need for a comprehensive vision

As is known, the concentration of populations with lesser purchasing power and greater social needs in certain neighbourhoods is a direct result of the process of urban segregation, that is, the phenomenon through which, due to their respective options in the land and housing market, different social groups tend to become separated in urban areas. As the capacity to choose a place to live depends on both personal and household income, those with greater income obviously have greater liberty when it comes to choosing where they want to live, while households of lesser financial means are generally pushed to places where prices are lower3. Hence, social groups with lower incomes and higher social needs tend to group in these urban areas with greater urban deficits.

The causes and effects of urban segregation on the increase in social inequalities in the major Spanish cities have been thoroughly studied (Garcia Almirall et al., 2008; Leal and Domínguez, 2008; López and Rey, 2008; Nel·lo, 2004). Firstly, they entail the paradox that municipalities with the biggest urban deficits and the greatest needs in terms of social services tend to have a more limited fiscal base, while areas where these needs are lower have more resources as a result of their capacity to levy fiscal charges. From a town planning perspective, this means that, to a certain extent, neighbourhoods and towns where the population with greater purchasing power is concentrated tend to have better public spaces and better public equipment and attract better private services. Conversely, areas with lower income populations are where deficits are historically higher and home to higher demands on public space and public equipment and have greater difficulties in financing their acquisition and implementation.

We encounter similar effects within the housing market, especially in countries like Spain, where the rental market has a relatively reduced weight and where most families own the housing units they live in: neighbourhoods inhabited by lower income populations are those where, in principle, buildings tend to be older and poorer quality and hence the owners experience greater difficulties in maintaining them. Furthermore, the concentration of rather problematic social situations in such areas reduces expectations as to property values and this influences land owners when considering engaging in possible renewal projects.

Moreover, in many cases, shortages in terms of public spaces, infrastructures, and housing are accompanied by high commuting costs, in terms of both economic resources and time, given the usually peripheral position of many of these neighbourhoods in relation to the centre of the respective urban area. Finally, we should also consider that segregated reproduction patterns amongst social groups, especially as far as education is concerned, may pose a significant barrier to equal opportunity and social mobility.

In Catalonia, however, the effects of urban segregation have been more benign than in other European countries and, since the restoration of democracy, there has been a considerable improvement in the standards of living of most districts and cities. The progress occurred due to the combined results of demand and efforts by local communities, the policies implemented by municipalities, overall economic development, and the dynamics of spatial integration, especially in the metropolitan area of Barcelona. Here, these dynamics have even resulted in a reduction in the cleavages in income distribution between the city and the rest of the area, steadily falling over the last two decades (Giner, 2002).

However, since the mid-1990s, the risks of rising social segregation have tended to worsen and, in certain places, some problems that seemed to have been overcome have re-emerged such as housing overcrowding, degradation of public space, and difficulties as to the provision of basic services. This development has been brought about mainly by two factors: the evolution of the real estate market in Spain and the change in demographic trends (Nel·lo, 2008).

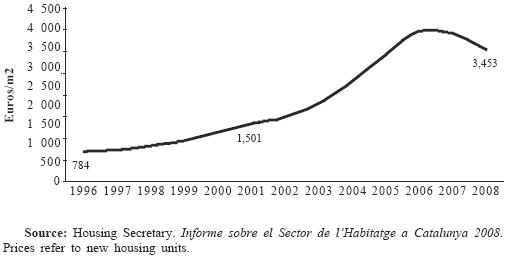

Firstly, the housing market witnessed a rapid increase in prices, which began in 1996 and lasted for more than a decade and did not stop until 2007 (Figure 2). As a result of these market developments, the percentage of income families have to allocate to housing costs has increased dramatically, to the point that accessing affordable housing became difficult for much of the population4.

Average housing prices in Catalonia (1996-2008)

[figure 2]

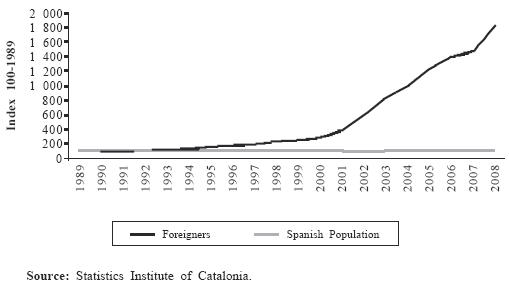

The rise, driven to a large extent by the financial sector, was further accompanied by a significant inflection of demographic dynamics. After a long period of stagnation, the Catalan population went from 6.2 to 7.5 million people in little more that a decade (1996-2009). This growth, as shown in Figure 3, was due largely to immigration inflows, which led to greater demand for housing, with the particularity that this demand came from a population segment which, in most cases, was barely solvent in comparison with prevailing market conditions.

Catalonia resident population, by nationality (1989-2008)

(Index: 1989=100)

[figure 3]

The combination of these two factors the housing market and demographic growth associated with immigration gave rise, on the one hand, to the re-emergence of substandard housing situations (especially as a result of overcrowding) and, on the other hand, to the concentration of social groups with lesser purchasing power in places where housing was relatively more affordable. As a result, we see the increased risk of social segregation and, in particular, the concentration of incidences of greater social need in those very neighbourhoods experiencing th e larger urban deficits: the old centres, 1960s and 1970s housing estates and areas resulting from processes of marginal urbanization.

The main objective of the Law on neighbourhoods is to address these problems, avoiding the degradation of living conditions in these areas and acting, where possible, on factors at the root of urban segregation5. The aim was, firstly, to promote social and spatial justice, so that all citizens, regardless of their place of residence, may have fair and equitable access to basic services and a quality environment. With that, the Law tries to prevent urban dynamics from contributing toward greater inequality in opportunities. Simultaneously, the Law has the objective of enhancing the city through social justice, on the premise that a city without social fractures is a more liveable, favourable, and appealing space for all inhabitants (Indovina, 1992).

Given these approaches, one could argue that problems relating to urban decline are primarily local issues and hence, their treatment through regional policies is inadequate. However, greater spatial integration leads to a situation where the residential market in which citizens and private sector actors make their decisions is not their immediate surroundings, but covers a much wider scope. Nowadays, urban segregation does not arise only amongst neighbourhoods in the same locality, but also between districts within the same urban area and even the whole country. Segregation has become a phenomenon of metropolitan and regional scope. Hence, a comprehensive vision covering the entire region is needed in order to fund and implement urban renewal projects. Only based on such visions may we obtain and equitably distribute resources to districts and municipalities experiencing the greatest difficulties in accessing such resources. Urban segregation in Europe in general and Catalonia in particular, is no longer a local matter: it responds to social and spatial dynamics of metropolitan scale at least and should be opposed with the resources and will of the whole society. This is the first lesson drawn from the implementation of the Law on neighbourhoods in Catalonia.

Financing projects, not problems

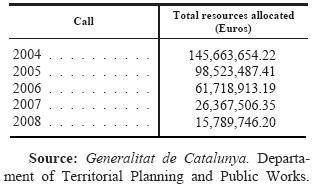

The second lesson to be learned from implementation states that, when allocating resources, it is much more adequate and effective to target projects rather than problems. The legal mechanism established operates very simply and it is to an extent inspired on the European Union URBAN programme.6 It is based on creating a financial fund by the Department of Territorial Planning and Public Works to which regional government resources are allocated. Based upon this resource pool, the government annually issues a call for municipalities seeking to carry out comprehensive rehabilitation projects in their neighbourhoods to submit applications. When approved, projects receive funding that varies from 50% to 75% of total project costs in accordance with the legislative framework.

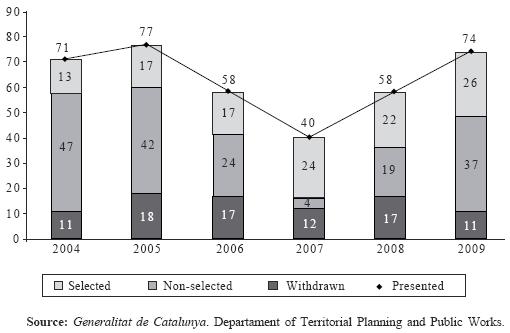

This raises the key issue of how to select which projects are to be awarded financing, because as shown in Figure 4, the number of applications presented each year by far exceeds the regional governments funding capacities.

Number of projects presented and selected (2004-2009)

[figure 4]

From the outset, it might seem obvious that the selection criteria should be based essentially on statistical evidence of deficits and social deprivation experienced by neighbourhoods. However, international experience demonstrates that choices made solely on the basis of these parameters may end up counterproductive. Factors contributing to worsening the objective difficulties of places affected by segregation are their stigmatisation by the media and the subjective loss of self-esteem amongst their populations7. Under these circumstances, to establish and publish a ranking of the most needy districts might contribute to consolidate this negative image. Furthermore, the fact that a locality is in poor objective conditions does not guarantee, in itself, that the intervention project designed by the respective municipality is the most appropriate to tackle the existing problems.

For these reasons, implementation of the Catalan law made recourse to a dual system of tables when selecting projects. First, the position of the locality is evaluated according to 16 objective statistical indicators on four areas: urban and equipment deficits, population structure and dynamics, environmental problems, and economic and local development deficits8. In order to be considered a special attention area, the neighbourhood in question must return a minimum score from this set of indicators.

After this first consideration of the reality in the area under study, we move on to the second evaluation process phase, based on the characteristics of projects submitted by councils. In this second phase which in terms of evaluation has equal weighting to that resulting from the socio-economic indicators priority is given to projects based on criteria such as the consideration of its comprehensive character, its overall coherence, the economic engagement of the municipal authorities, the parallel undertaking of complementary actions, and others.

From merging the two groups of indicators statistics and project related features we obtain the score assigned to each proposal and, based on this score, available resources are then allocated by each call. On the one hand, the use of these objective parameters is there to avoid a possible perverse effect in the distribution of resources by a supra-local body: the risk that the allocation process is reduced to a competition between municipalities in need (Atkinson, 2003). On the other hand, this analysis of the benefits and effectiveness of the project submitted by a town council is there to ensure allocated resources are used efficiently and in line with the legally stipulated objectives. Thus, it can be stated that the programme is not only a tool for neighbourhoods with problems, but a device for helping neighbourhoods with projects: projects conceived to address existing problems.

The transversal nature of the intervention

A third lesson deriving from implementation of this law reflects the need for an integrated approach to urban renewal problems: only by intervening simultaneously on urban and social shortcomings can a policy be reasonably effective and consistent in the improvement of standards of living. This proposal achieves across the board agreement at least from the theoretical perspective (Cremaschi, 2005; Gutierrez, 2008; Parkinson, 1998), but has traditionally encountered great difficulties in practical application by administrative structures set up in accordance with the principle of the division of tasks and the sectorial budgetary distribution. In the implementation of the Law on neighbourhoods, the intention was to encourage such a transversal approach by means of three instruments: the requirement for intervention across a number of fields in order to qualify for funding, the creation of complementary programmes by various Generalitat departments, and the establishment of integrated monitoring mechanisms.

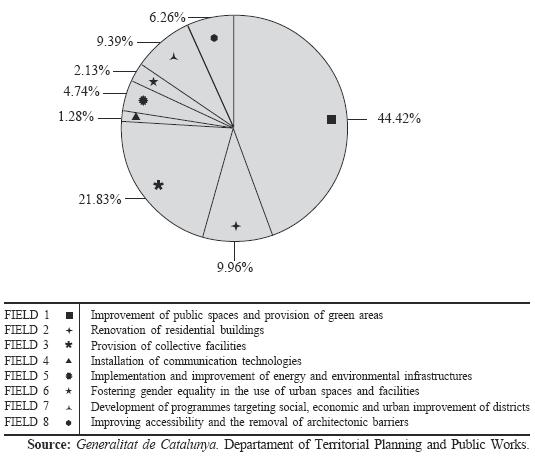

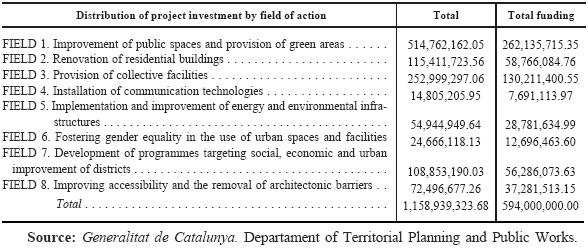

Regarding fields of intervention, the law sets out eight different areas in which action can be taken by municipalities, covering in this way a wide diversity of fields. It is worth recalling their reach and ascertaining the scopes prioritised by the city councils when allocating investment (Figure 5 and Table 1).

1. Improvement of public spaces and provision of green areas (road paving, placement of trees, lighting, landscaping).

2. Renovation of residential buildings (façades, gutters, elevators, roofs).

3. Provision of collective facilities (civic centres, elderly homes, and senior centres).

4. Installation of communication technologies (wiring of buildings, establishment of Wi-Fi areas).

5. Implementation and improvement of energy and environmental infrastructures (pneumatic waste collection, underground containers, opening recycling centres, encouraging renewable energies, water saving devices).

6. Fostering gender equity in the use of urban spaces and facilities (introduction of a gender perspective in the provision, design, and configuration of public spaces and facilities).

7. Development of programmes targeting social, economic, and urban improvement of districts (support activities for groups at risk of social exclusion, training programmes, commercial revitalisation.)

8. Improving accessibility and the removal of architectonic barriers (extension of sidewalks, construction of ramps, installation of escalators, and removal of obstacles).

Distribution of investment by field of action (2004-2009)

[figure 5]

Total investment in euros by field of action (2004-2009)

[table 1]

In order to enhance the programmes transversal nature, the law and its regulatory framework stipulate that the score obtained for each project submitted in the selection process be proportional to the number of fields of action. This has led to the result that, out of the 92 projects selected in the first five calls, 71 intervene in all eight possible fields, 8 in seven and 7 in six. The least frequently included field of intervention (the promotion of new technologies) is present in a total of 79 projects. Indeed, no matter how transversal, a tool local in scope and endowed with limited resources may not prove to be a decisive influence on the evolution of structural variables such as the labour market, migratory flows, and the housing market which should be handled with the appropriate economic and fiscal policies. However, the level of transversality achieved by the Law on neighbourhoods may represent a significant advance toward avoiding a situation where territorial and urban issues exacerbate social problems arising from the general evolution of these variables.

In efforts to cover all material aspects of neighbourhood life, complementary actions provided by other regional government departments9 proved very important. Worth mentioning among them is the Jobs in Neighbourhoods programme run by the Department of Labour through the Employment Service of Catalonia, which resulted in the establishment of agreements in 81 of 92 districts covered by the law and providing them with occupational training and school-to-work transition programmes with the commitment of 30 million total investment between 2004 and 2008. The Department of Health has conducted studies on the status of public health and healthcare in the districts through the Health in the Neighbourhood programme, having intervened in 30 districts in the first three programme calls. Furthermore, the Department of Environment and Housing has set up specific lines of support for the renewal of collectively shared building areas for 37 districts, and the Department of Home Office, Institutional Relations and Citizen Participation has financed citizen participation processes in a further 24. Finally, the Catalan Institute of Soil has signed agreements to carry out urban renewal activities (in particular, the replacement of obsolete housing with new units) in 24 programme districts with investment, in parallel to that generated by the law, estimated at 200 million. In the future, the coordination of actions undertaken in the fields of Education, Social Action, and Immigration may prove highly productive.

The institutional expression of these transversal actions is the creation of an Evaluation and Monitoring Committee in each neighbourhood benefiting from the programme. These committees are the coordinating body for each project and are made up of, on the one hand, representatives from seven Generalitat departments (Territorial Planning and Public Works, Environment and Housing, Governance, Social Action, Economy and Finance, Health and Labour, and the delegation of the regional government in the respective province), and, on the other, the city services directly responsible for the district management. Thus, the Evaluation and Monitoring committees become bodies with great potential when it comes to bringing together, in the presence of the respective mayor, all Generalitat and municipal council services related to local life. However, precisely because of their complexity, the committee meetings cannot be very frequent (on average once per year in each district) and do not replace daily Generalitat and municipality activities. The Law on neighbourhoods thus sets out a core infrastructure for integrated and transversal action in the urban areas within this special programme but the process of administrative adaptation in order to act more territorially and less sector-oriented (in neighbourhoods requiring special attention and in many other areas) still requires a great deal of further change (Amill et al., 2009).

The key role of public investment

The fourth lesson derived from the implementation of the Law on neighbourhoods is the acknowledgement of the key role that public investment plays in urban renewal processes. As discussed above, under current market conditions, the most difficult social situations tend to cluster where prices are lower. This leads, firstly, to difficulties in the provision and access to basic services, and, secondly, to increasing risk that average house prices in this area tend to move further and further from those of the city as a whole. In this context, investment and government spending on districts, besides having a direct impact on social problems and urban deficits, becomes a catalyst for attracting more investment from other sources (public or private).

The first immediate effect of the Law of neighbourhoods10 was to provide greater resources for tackling social problems specific to each neighbourhood. This enabled authorities to provide special attention to those groups that are most exposed to risks of exclusion (the elderly, young, and recent immigrants), as well as to promote economic activities, boost trade, and foster gender equity in access to services and public spaces. The resources rendered for these purposes by the programme, 134 million of expenditure incurred in the first five years of implementation (Table 1, fields 6 and 7), come in addition to (and do not replace) regular budgets allocated by the government and municipalities for social provisions in general in these very same districts (unemployment benefits, minimum re-integration subsidy, and others). Thus, programme areas gain additional resources, not only to provide direct aid to individuals, but also to stimulate community programmes that promote equal opportunities in access to income and services across the whole of the district.

A second effect of public investment in the neighbourhoods covered by the programme has been to reduce deficits in town planning, equipment, and housing conditions currently witnessed in these areas. These deficits represent a significant obstacle to quality of life and decisively impact the housing price formation mechanism and the resulting dynamics of segregation. In the first years of programme implementation, municipalities allocated a substantial share of available resources to this purpose. Thus, as seen (Table 1, field 1), almost half of the investment committed ( 515 million) has been designed to meet needs relating to upgrading public spaces and providing green areas. This comes as no surprise: in neighbourhoods requiring special attention, public spaces not only experience deficits from the time of their very opening, but are often under great pressure (because their available area is often limited and because residents have little space indoors.) Their expansion and recovery is therefore essential to improving the quality of community life and to solving the commonly encountered conflicts over the use of collective spaces.

The investment of 55 million in the improvement of environmental infrastructures (waste collection and treatment, the water and energy cycles) pursued the same goal of reducing deficits that impair standards of living and equalising the status of all the neighbourhoods of the same municipality. This also applied to the investment in facilities for collective use ( 253 million). However, a non-negligible additional aspect is worth noting: many districts selected by the programme not only lack facilities for their own inhabitants, but also amenities and services attractive to the city as a whole. This feature, found especially in the mass housing estates and areas arising from marginal urbanisation, has deprived these neighbourhoods of centrality and converted them into areas seldom visited by non-residents. The Neighbourhood Programme seeks to remedy this situation through the location of facilities in these neighbourhoods which, in addition to serving their neighbours, are used by the entire city, such as the Frederica Montseny Civic Centre, in Manlleu, or the renovated Coma-Cros factory, in Salt. This has helped to attract other public and private facilities, whether municipal, county, or even of regional reach (such as the district courts in Balaguer or the Palace of Justice and the Fundació Catalana de lEsplai headquarters in the district of Sant Cosme in Prat de Llobregat).

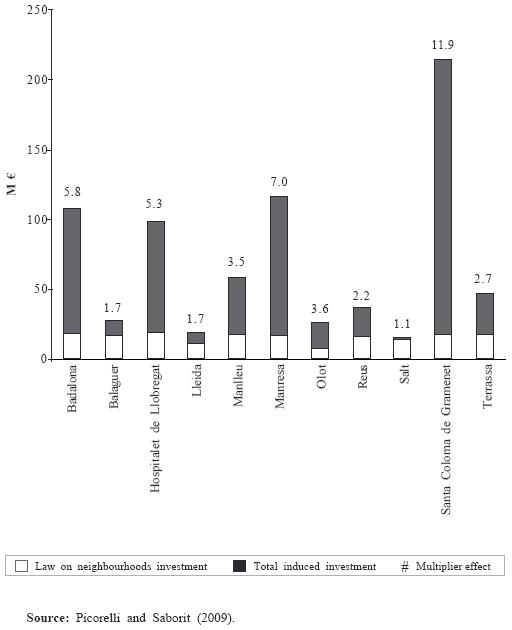

Together with the direct effects of the neighbourhood investment programme described above, there are other indirect effects. First, the existence of the Law on neighbourhoods framework generated a catalyst effect in attracting complementary public investment to these neighbourhoods, either by the council itself, other Generalitat departments (some of which have created, as seen, their own specific binding programmes), and the central state. It is still too early to quantify the scope of this catalysing effect but early estimates (Picorelli and Saborit, 2009) based on the experience of neighbourhoods in the first call, indicate that each euro spent under the auspices of the Law on neighbourhoods achieved a multiplier effect of 4.41 (see Figure 6). Thus, from the 179.7 million allocated by the Law to the 11 first call districts (excluding the City of Barcelona), 793.6 million has been generated in public investment11.

Law on neighbourhoods investment multiplier effect, 2004 (excluding Barcelona)

[figure 6]

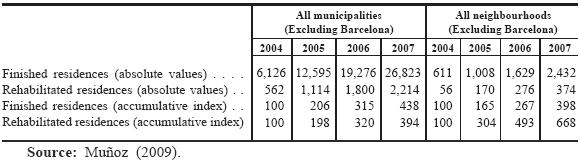

Furthermore, the concentration of this volume of public investment, either directly from the programme or attracted precisely due to it, has had a powerful effect on stimulating private investment. Indeed, solving the built environment and facilities deficits is a prime incentive for private investment in neighbourhoods, especially by property owners. These, in a context of neighbourhood shortcomings and deteriorating standards of living, would have little incentives to renovate their own properties and would tend more to sell, even at low prices. With the implementation of the Law, owners see the situation reversed as a result of public investment and act accordingly. Aggregate data are difficult to obtain on the total amounts of such investment, but there are very significant indicators relating to private sector investment renewal activities (Muñoz, 2009, for data see Table 2).

Building, construction and renewal activities in Law on neighbourhoods first-call municipalities and neighbourhoods (2004-2007)

[table 2]

Let us, for example, consider the municipalities to which the neighbourhoods benefiting from the first call belong (excluding the city of Barcelona). In them as a whole the number of finished housing rose from an index of 100 in 2004 to 394 in 2007, whereas in the very areas of neighbourhoods benefiting from the programme growth soared from 100 to 668. It is also significant that, in spite of the trend of new building to concentrate in new, developing areas of the city and not in already consolidated districts like the programme ones, new housing dynamics do not greatly differ in their respective municipalities average. Thus, while in indexed numbers the dwellings completed in all municipalities (again excluding Barcelona) rose from 100 to 438, neighbourhoods subject to renewal processes jump from 100 to 398. Additionally, if we consider not only effectively rehabilitated or completed homes, but also construction expectations (expressed as construction or rehabilitation licenses and permits), in none of the districts analysed did the expectation of housing production slide or register any decline between 2004 and 2007, contrary to what took place in some of their respective municipalities.

Given these dynamics, we may argue that, depending on market conditions, such processes may lead to rising property prices and to fostering gentrification processes12. One could think that this situation would affect urban centres especially, more than housing estates or spaces emerging out of marginal urbanisation, as these are, fortunately or unfortunately, areas far from being exposed to this problem. However, this risk has been effectively staved off in the Catalan case due to the introduction of policies to ensure social housing within any substantial new urban development13. Another factor has contributed to avoiding this risk: in the neighbourhoods benefiting from the first programme call (excluding areas within the city of Barcelona) 239.95 million of public investment went into housing. Thus, the investment devoted to social housing in these areas exceeded even the resources allocated under the Law on neighbourhoods (Picorelli and Saborit, 2009).

Furthermore, it should be noted that in Catalonia, as in the whole of Spain, property ownership is the dominant form of tenure, with 86% of households owning their own housing unit. This does not always have positive effects in terms of housing access but has a welcomed side effect in terms of renewal: whenever there are improvements in the neighbourhood, residents themselves see that it adds value to their property and therefore share an objective interest in improving it. The predominance of ownership over renting also leads to deeper roots being set down in the neighbourhood, thus inhibiting the tendency of families who experience an increase in their level of income to relocate to other areas of the city. This clearly differentiates the Catalan experience from those cases where urban renewal policies were implemented in areas where rental is the predominant property type, whether private (in which case we do in fact witness transfer processes in the resident population), or public (in which case, tenants obviously have no direct financial interest in the renewal of the homes where they reside).

A new type of relationship between regional and local government

The fifth lesson confirmed by the Law on neighbourhoods: it is no longer possible to develop a wide reaching urban policy without intense exercise of inter-administrative cooperation. Detailed above are the reasons explaining why the intervention of supra-local levels of government in urban regeneration processes is essential. If the neighbourhood renewal has social cohesion as its main objective, then this necessarily must comprise some sort of public revenue transfers and hence the intervention of both higher and local authorities is necessary.

Thus, the Generalitats presence is required for spurring, selecting, funding, and evaluating projects, but it would be inappropriate for the regional government to try to perform such actions on its own: proximity is a prerequisite for urban policy success. Correspondingly, trying to intervene in the local arena directly from higher bodies central or regional can often lead, as the European experience has shown, to errors in assessment and action (Gutierrez, 2008; Parkinson, 1998).

That is why this law has sought to assign full responsibility for project implementation to the municipalities. Thus, the city council the institution with direct knowledge of the problems and potentials of each neighbourhood is charged with designing and monitoring project implementation. From this perspective, the neighbourhoods programme seeks stricter compliance with the principle of subsidiarity and may be considered, since its enactment, as an essentially municipalist project one where the regional government relies on councils to promote and finance projects and explicitly eschews any claims to leadership.

This spirit of cooperation between levels of government has extended not only to programme design and implementation but also the very process of project selection. Thus, the law attributes responsibility for the selection and allocation of resources to the Comisión de gestión del fondo de fomento de barrios y áreas urbanas que requieren una atención especial management fund committee for the development of neighbourhoods and urban areas requiring special attention. This committee, consisting of a total of 30 members, is equally made up of representatives from various Generalitat departments and local government associations (the Catalonia Federation of Municipalities and the Catalan Association of Municipalities), as well as professional architect and technical specialist orders. We should point out that in five years and six calls for projects, the Commission distributed resources amounting to 1,158,939,323 to 117 projects taking place in 94 municipalities, with decisions always having to be taken unanimously. This might be proof that the system of tables and parameters put into effect by the Law was well designed and appropriately subject to implementation. However, it also clearly signals the desire for transparency and multi-level governance that has been one of the main features of this programme set up both by the Generalitat and the municipalities.

As stated above, enforcement of this Law is meant to complement inter-administrative cooperation of a vertical nature with horizontal intra-administrative cooperation. The latter is an essential prerequisite to achieving a transversal approach to policies and has often resulted in great complexity, within the Generalitat as well as in the municipalities. As noted before, the main expression of both inter-administrative and intra-administrative cooperation is the Comité de Avaluación y Seguimiento Appraisal and Monitoring Committees in each neighbourhood, which gathers into a single body all the regional and local administration departments with competences over local life.

Potentials and challenges of sharing finance

The shared funding model that characterises the programme corresponds to this willingness to use public investment as a lever to transform neighbourhoods. The importance of and difficulty in jointly managing the funding is the sixth lesson derived from implementation of the law.

As mentioned above, the funding mechanism is at the heart of this legislative framework and works simply: the Generalitat creates a financial fund for neighbourhoods from which municipalities receive project funding amounting to 50% of total planned investment. However, this apparent simplicity of the approach involves considerable complexity when it comes to application. The difficulties have three origins: the adequacy of resources, administrative management, and the atypical nature of planned spending.

Regarding the adequacy of resources, it should be noted that programmes under the auspices of this legislation entail an economic commitment which is highly significant for all authorities involved. The Department of Planning and Public Works allocated 99 million to each call to be borne by the relevant multi-annual expenditure reserves (in 2009, the total annual department budget was of 1,524 million). This is undoubtedly a substantial financial sum but, in relative terms, the commitment is even higher for the vast majority of municipalities involved in the programme. Indeed, programmes in the first five calls had an average budget of 10.7 million. This means that municipalities must make an average contribution of more than 1.3 million per year and neighbourhood. Thus, municipalities involved in the programme had to allocate, for each of the four operational years, contributions ranging from 22.5% (in municipalities with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants) and 2.24% (in those municipalities with between 100,000 and 500,000 inhabitants) of their annual budgets. The efforts of council authorities participating in the programme are thus self-evident.

It is therefore of little wonder that, with the beginning of the economic crisis, in 2008, some voices have expressed doubts as to the ability of Catalan municipalities to continue meeting these commitments. However, as explained below, to date these pessimistic forecasts have not proven accurate. Despite the current difficulties, council authorities are honouring, in general, the commitments made both to citizens and to the Generalitat as to the implementation of neighbourhood programmes. This attitude, rather than opting for non-compliance, undoubtedly contributes toward proving them right when requesting a review of the local finance system.

Along with problems in resource adequacy, we must take into account the complexity of the shared financing mechanisms. In summary, the funding circuit involves the following steps: (i) once the project is selected by the Fund Management Committee, the council receives a notification as to the provision of aid from the regional minister of Planning and Public Works; (ii) based on the list and the scope of planned actions in each neighbourhood, the Generalitat and the municipality establish an agreement that includes an economic and financial plan detailing projections for the implementation of measures over the four-year programme life cycle and the annual contributions that each institution is to make to render them viable; (iii) the municipality starts the tender process and the implementation of measures and, as it proceeds, certifies the amounts deployed to the regional government; (iv) the regional government checks the performance of these actions and the accuracy of forecast expenditure before then transferring payment to the municipality.

It should be noted that the attempt to introduce European funding into this circuit failed to a certain extent. Indeed, the Generalitat sought to allocate part of the European Regional Development Funding (ERDF) that it manages to meet the financial needs of the programme. Although the amount initially considered for this purpose amounted to only a small part of the total resources ( 33 million of eligible expenditure, of which 16.5 was to have been ERDF funded), its inclusion forced the adoption of a number of complex and stringent new regulations that have affected the financial management of the entire programme. For smaller municipalities, these regulations have proved rather complex and sometimes even retarded progress. This forced the rescheduling of eligible expenses so that at the end of the 2004-2008 period, the actually implemented ERDF Programme European funds totalled only 5.5 million euros.

Finally, according to its design, funding for comprehensive renewal projects involves a form of budgetary planning and execution that is atypical in many of the municipalities involved. Municipal budgets are traditionally structured in keeping with sectorial lines, covering annual periods, and applying generically to the whole municipality. However, the implementation of the Law entails the need to integrate resources from various departments and municipal services, to adapt to non-annual schedules, and to concentrate in a particular area. Not surprisingly, several municipalities have encountered difficulties in adapting their structures and switching from sectorial, annual, and generic budget criteria to transversal, programmatic, and geographically circumscribed approaches.

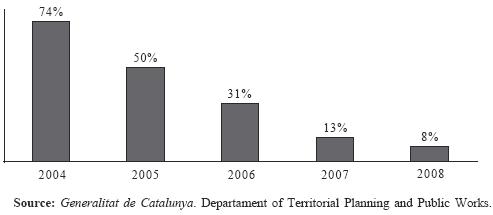

However, despite the complexity of funding mechanisms, the use of resources has been fairly satisfactory. Thus, as of December 31, 2009, investment and total expenditure justified by the municipalities to the Department of Planning and Public Works was 348.1 million. This reflects how all municipalities benefitting from the first call have justified 74% of the planned spending and financial programme spending to date. In two districts, the investment made had already reached 100% of expenditure, whereas the remainder required an extension of one or two years to complete the programme, something that was already foreseen in the legal stipulations. Delays in performance resulted especially from the fact that during the first year of the programme very little expense was in fact incurred14. Therefore, although a good proportion of programme projects was carried out in five or six years, instead of four years, the level of Law on neighbourhoods financial implementation can be advantageously compared to rates of investment compliance attained across public administration of Catalonia and Spain.

Percentage of invested resources with respect to planned spending (by calls, 2004-2008)

[figure 7]

[table 3]

Local community involvement

In the same way that the intervention of an administrative body alien to the local reality presents, as previously stated, many problems when dealing with neighbourhood problems, experience has shown that renewal projects are hardly likely to achieve their objectives without involvement of local communities. This is the seventh lesson drawn from implementation of urban renewal in Catalonia.

As is known, the existence of urban deficits and social problems often entails a lack of social interaction, difficulties in conviviality, and self-esteem problems for residents. These circumstances make it necessary for the development of urban renewal projects to prioritise the empowerment of local citizens when deciding on how to advance the area where they reside (Atkinson, 2003; Parkinson, 1998). To achieve this, neighbours need to be involved in the definition, implementation, and evaluation of urban renewal programmes. Only in this way can intervention become a collective project by the neighbourhood (and not just for the neighbourhood), a project that, if necessary, neighbours may require the authorities to accomplish15. In this way, far from being mere beneficiaries, local communities become activists in the neighbourhood improvement process.

Based on this premise, the Law on neighbourhoods provides for the participation of representatives from neighbourhood bodies and associations in the monitoring and evaluation committees formed in each district. This allows them to be involved directly in monitoring and evaluating results at the highest level, i.e., in the body that controls due programme compliance. However, experience has also shown that resident programme participation should not be reduced to this scope.

This is so, firstly, because each neighbourhood committee is formed once the resources have been allocated and execution of the programme has begun. Correspondingly, beginning at this moment, local community participation would be excluded from the crucial process of project design. Given this eventuality, it should be noted that those municipalities that included resident participation right from the outset of programme definition have achieved excellent results. In this regard, the possibility was raised that future programmes, may have a year 0, i.e., a period in which, once resources are allocated to municipalities, before initiating proceedings, they prepare, define, and design programme content in conjunction with neighbours.

Secondly, the need to expand citizen participation beyond evaluation and monitoring committee meetings derives from the very nature of this body. In fact, as mentioned, given its wide and heterogeneous nature, these committees meet only once a year. Thus, neighbourhoods with greater community involvement are those where other permanent participatory mechanisms between neighbourhood organisations and the municipality have been created. Likewise, very encouraging results are obtained in neighbourhoods where, together with the ongoing participation process, consultation took place with the specific objective of defining, for example, the design of a square or a street.

Finally, we should point out what might seem obvious. The process of resident involvement requires, of course, the willingness of governments to act with transparency and to engage in dialogue through to the end of the process. But the richer the neighbourhood social life, the greater the organisation of neighbours, the more successful this process will be. Therefore, the presence of a strong associational life and a representative local community movement is another requirement for the neighbourhood involvement process in order to ensure that the local improvement proves successful.

The importance of capitalising on experiences

The implementation of the Law on neighbourhoods has led to innovations in the design and implementation of policies and in various areas of Catalan public administration. This has meant that successes and failures in programme implementation represent a collective learning process. The need to capitalise on this experience to improve policies is the programmes eighth lesson.

Indeed, since 2004, a remarkable body of knowledge has accumulated in teams that, from the Generalitat to the municipalities, have been involved in the management of such programmes. Likewise, private consultants and institutions have worked together with municipalities in the development and implementation of projects and have gathered a body of highly valuable knowledge as well16.

Furthermore, the technical staff in charge of programme coordination about a hundred across all of Catalonia represent a new professional profile non-existent in Catalan municipalities before, with the exception of some large municipalities. Taken together, this body of knowledge constitutes a valuable social capital that has enriched the experience accumulated in urban renewal policies in Catalonia since the return of democracy in the late 1970s.

In order to capitalise on this knowledge, the Catalan Government decided at the beginning of 2007, to promote an integrated network for all municipalities participating in the programme with the aim of sharing and evaluating experiences. This scheme of cooperation, called Red de Barrios con Proyectos Network of Neighbourhoods with Projects seeks to articulate and strengthen relationships of a more or less informal nature that have been woven between the many institutions and technicians involved in programme implementation. The aim was to avoid fragmentation and isolation amongst local actors, something witnessed in urban renewal programmes in other European countries (Atkinson, 2003).

The network includes elected officials and municipal technical staff, as well as technical specialists from the Generalitat (from both the Department of Planning and Public Works, and other departments working together on the programme), technicians from other local authorities (in particular the provincial councils), private consultants, neighbourhood associations, and researchers engaged in academic work on issues relating to the Law on neighbourhoods implementation processes.

The network operates four thematic working groups (Public Spaces, Accessibility, and Sustainability; Facilities and Residential Building Upgrading; Social and Gender Programmes, and Economic and Commercial Promotion; Citizen Involvement) whose coordination and dynamics are the responsibility of members of staff hired by the Department of Planning and Public Works. Each working group organises a series of seminars and workshops open to all network members, while also making visits to specific operations.

The results of network activities include the creation of a catalogue of good practices so that all participating municipalities and those wishing to join can source a list of successful experiences, along with the regular publication of a digital newsletter with information and a website with the relevant calendars, blog, forum, links directory, and file repository17. One intangible, but not insignificant, result is the fact that the existence of the network has played an important role in nurturing a certain sense of community amongst people and institutions responsible for promoting and implementing programmes.

However, the willingness to cooperate has not stopped within the boundaries of the region, but has also extended to other regions of the European Union. In fact, as already mentioned, since its inception the Law on neighbourhoods was largely inspired by the experience of the European URBAN Programme and, despite the fact that resources from this programme have long since disappeared, and other European funds proved unsuitable for programme purposes, the Government has seen fit to promote different cooperation experiences within the European framework. These initiatives have a threefold purpose: to promote the interest of European institutions in urban renewal policies, capitalise on experiences in other regions and European states in this field, and disseminate the lessons of the Law on neighbourhoods. Thus, within the URBACT EU initiative framework, the Generalitat has promoted and led the creation of two successive working groups on urban renewal (called CIVITAS and NODUS), consisting of European regions and cities involved in this field in Italy, Poland, Britain, Romania, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Spain18.

Another key aspect for conceptualising and capitalising on the experience of the Law on neighbourhoods has been the attention given to universities and professional orders, and the neighbourhood programme has been the subject of attention and study by several universities in Catalonia and abroad. Proof of the interest in the initiative across both professional and academic fields is the award received at the International Union of Architects at its 23rd World Congress held in Turin in 2008 and granted to the Government of Catalonia for its pragmatic approach to urban renewal and urban development within the existing urban fabric.

The commitment to evaluating results

Evaluation of the implementation and outcomes of public policies is a challenge that, traditionally, Catalan and Spanish administrations have given only a limited response to. The need to address this issue, a precondition of rigour and transparency, and in order to improve future programme implementation, is the ninth lesson from implementing the Law of neighbourhoods.

In fact, the same law did indeed incorporate its own assessment mechanisms. These are of two types: the first is assigned to the Evaluation and Monitoring Committee in each district, which is held responsible for drafting a final evaluation report. Second, the Generalitat of Catalonia is required, after an initial four-year period of enforcement, to make an assessment of the objectives achieved and the needs of continuity, without prejudice to the ongoing proceedings.

Regarding the first commitment, the Generalitat established that each final evaluation report was to contain a performance assessment of results in terms of territorial planning, economic and commercial activity, environmental aspects, social cohesion, and gender equality. To achieve this, as stipulated by the legal framework, the report should detail the extent of programme implementation in terms of actions and funding provided, any deviations in programme implementation, the relationship between results obtained and objectives set, the impact of interventions on the built environment, on the deficit in social services and facilities, and on demographic, social, and economic problems. As will be explained, the report is decisive in establishing the continuity of further joint actions involving the Generalitat and the city council in the locality.

The obligation to conduct an overall evaluation of the programme results has been met by the Government through the development of various internal and external reports, with the latter commissioned to various university research centres, private consultants, and other government bodies. This set of materials has been submitted to the Catalan parliament and its findings published in a collected volume19.

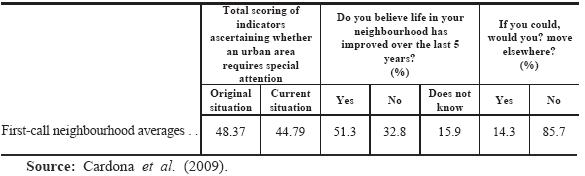

From this assessment derives a large number of useful conclusions designed to guide future programme development. Given its summary format, the study on the social impact of implementation (Cardona et al., 2009) is of particular importance. This fairly simple exercise consisted of surveying those districts already into their fourth programme year, with recourse to the same socio-economic statistical evaluation procedures carried out at the time of selection. The results contain certain limitations since action effects are not always immediate and further analysis is needed, especially as many projects were still pending completion. However, the results themselves are very significant. As explained above, the system of parameters is the result of 16 statistical indicators accounting for demographic, urban, economic, and social development. The higher the total score of each district, the more serious the problem. Now, as shown in Table 4, in the fourth programme year, the average score for first-call neighbourhoods dropped from 48.37 to 44.79, hence, not only did it not worsen, but it actually improved by 7.4% overall. This improvement has been significant in 6 of the 13 districts where scores dropped by more than 10%, in another three districts there was more moderate improvement, a drop of between 0 and 10%. Finally, four neighbourhoods have continued to see their problems worsen, despite programme implementation, and witnessed an average 6.6% increase in their scores.

Some indicators on compliance with Law on neighbourhood objectives in first-call municipalities

[table 4]

This objective improvement was confirmed by a survey of citizen perceptions (Cardona et al., 2009): in 11 of the 13 first-call districts, the number of citizens who considered that life had improved in recent years is higher than those who believed otherwise. Furthermore, in each of the 13 districts, a large majority of citizens (85.7% on average) stated that, even if in a position to do so, they would not live elsewhere.

The results therefore show that the position of areas benefiting from the law is far from easy, but in the first four programme years (2004-2008), despite tensions in the housing market and the continuous arrival of people with significant social needs, there does not seem to have been any significant deterioration. On the contrary, it can be said, with due caution, that the findings in most districts where the renewal process is in its final stages point to the situation having improved considerably, both objectively and in terms of citizen perceptions. However, it should be noted that the survey was carried out in the first half of 2008, when the effects of the economic crisis that impacted the Spanish economy had not yet fully shown its effects.

Adapting to changes

The tenth lesson to be drawn from the experience of districts in the Catalan neighbourhood programme is the need to maintain a constantly critical attitude toward the intervention instruments adopted. Indeed, analysis results in a reasonably positive general assessment for the first years of implementation. Nevertheless, there is a clear need to refine and adapt to economic, social, and political changes.

The first of these changes, and certainly the most decisive, is the alteration in the prevailing economic conditions. Whilst the first three years of operation saw the programme implemented within a context of Catalan economic expansion, as of 2008 the world entered a phase of instability and obvious difficulties. The effects this crisis may have through changing real estate market conditions and migration flows on the accentuation of social segregation processes are uncertain. However, it is clear that in programme neighbourhoods, and others in similar situations, social issues such as unemployment and the risk of exclusion are already significantly apparent. This necessarily requires increased cohesion policies.

The second change is of a political and administrative character. As stated, with the fifth call (corresponding to 2008) the programme reached 92 neighbourhoods, 1 billion of allocated investment, and benefits a population representing more than 10% of Catalonia. The regional government commitment was to reach 100 neighbourhoods, a limit over which the programme could become denaturalised.

Based on these findings, and after examining the evaluation exercise outlined above, the government proposed the introduction of certain modifications to programme implementation, as approved by the parliament of Catalonia in the 2009 budget legislation. The amendments have the following objectives:

a) Enhancing the performance of the Law on neighbourhoods as a tool for the development of social cohesion policies on a territorial basis and transversal in nature, especially necessary in a recessionary period.

b) Achieving the number of 100 districts benefiting from special attention under the programme and, after reaching this number, establishing limit measures to preserve scopes of action consistent with the specificity of the instrument.

c) Maintaining cooperation and aid in neighbourhoods that have already implemented all the actions foreseen in their respective programmes.

d) Facilitating programme access to smaller municipalities experiencing significant difficulties in meeting programme contribution costs.

e) Maintaining, despite budgetary constraints, the annual financial allocations to the Neighbourhood Management Fund and complement them with other funds, such as local government, health, employment, and others.

f) Deepening innovations achieved in the administrative structure and in the working methodologies enabling administrative cooperation between the Generalitat and municipalities, the transversal nature of policy implementation, and the involvement of neighbourhood organisations and associations.

Consequently, following the 2009 call, when the neighbourhood programme entered its second four-year period of implementation, changes were made to allow for the existence of three different approaches to realities on the ground: comprehensive intervention programmes, neighbourhood contracts, and the specific programme area for smaller municipalities.

Regarding the comprehensive intervention programmes, the target of 100 districts participating in renewal processes has been achieved. Henceforth, new localities will only be added depending on the number of those completing their respective programmes, i.e., each call accepts the same number onto the programme as neighbourhoods terminate their works. The idea is to maintain the consistency and specificity of the programme and the administrative ability to monitor and evaluate the ongoing projects with every possible guarantee.

Likewise, neighbourhoods completing the measures planned by their respective programmes are eligible for a new scheme called a neighbourhood contract. The objective is to retain special collaborative mechanisms in those neighbourhoods that, despite the programme work already done, continue to require special attention from the authorities. As seen before, the Neighbourhood Programme is, in some respects, a type of shock intervention, which seeks, through the temporary concentration of procedures, to reverse the dynamics of degradation. However, the process of profound neighbourhood renewal is usually a task for more than a generation. Furthermore, it has not seemed advisable to abruptly discontinue the investment, let alone when special needs exist in a period of crisis. The contracts bind the Administration and the Generalitat as a whole with each municipality and provide local Development Programme funding. As noted above, actions to be financed are to be decided upon by a final evaluation report from the respective council, which must submit it to the Evaluation and Monitoring Committee on completion of all project procedures.

Finally, the creation of a specific sub-programme is envisaged to promote comprehensive rehabilitation programmes in municipalities with under 10,000 inhabitants. The objective of this mechanism, known as Programa de villas con proyectos, is to facilitate the incorporation of smaller municipalities as programme beneficiaries, resolving the main stumbling block they have faced so far: the inability to meet the 50% funding contribution requirement. In fact, the law stipulated that government financing of projects could range from between 50% and 75% of the total so that, as from the 2009 call, it was established that for municipalities with under 10,000 residents regional government funding would account for 75% of the total. Under the auspices of this alteration, 15 small and medium municipalities have already been able to proceed with project programmes.

The need to continue innovating and to adapt to changes in order to defend social cohesion in all towns and cities in Catalonia is, therefore, the tenth and final lesson from the experience of the Law on neighbourhoods, with all its strengths and limitations.

References

Albors, J. (2008), La millora urbana des dels barris: marc instrumental, intervenció integral i oportunitats. In J. M. Llop et al. (eds.), Ciutats en (Re)construcció: Necessitats Socials i Millora de Barris, Barcelona, Diputació de Barcelona, pp. 259-268.

Amill, J. et al. (2009), La transversalitat en el model de gestió del programa dintervenció integral als barris. In O. Nel.lo (dir.), La Llei de Barris. Una Aposta Col·lectiva per la Cohesió Social, Barcelona, Generalitat de Catalunya, pp. 116-130.

Atkinson, R. (2003), Addressing urban social exclusion through community involvement in urban regeneration. In R. Imre and M. Raco, Urban Renaissence? New Labour, Community and Urban Policy, Bristol, Policy Press, pp. 101-120.

Borja, J. (1986), Por unos Municipios Democráticos. Diez Años de Reflexión Política y Movimiento Ciudadano, Madrid, Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local.

Cardona, Á. et al. (2009), La incidència social de la Llei de Barris. In O. Nel·lo (dir.), La Llei de Barris. Una Aposta Col·lectiva per la Cohesió Social, Barcelona, Generalitat de Catalunya, pp. 60-74.

Castells, M. (1983), The City and the Grassroots. A Cross-cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements, London, Edward Arnold.

Cremaschi, M. (2005), LEuropa delle Città. Accessibilità, Partnership, Policentrismo nelle Politiche Comunitarie per il Territorio, Firenze, Alinea.

Domingo, M. and Bonet, M. R. (1998), Barcelona i els Movimients Socials Urbans, Barcelona, Fundació Jaume Bofill.

Garcia Almirall, P. et al. (2008), Inmigración y espacio socio-residencial en la región metropolitana de Barcelona. Ciudad y Territorio. Estudios Territoriales, xl (157), pp. 727-742.

Giner, S. (2002), Enquesta de la Regió Metropolitana de Barcelona. Condicions de vida i Hàbits de la Població. Informe General, Barcelona, Mancomunitat de Municipis de lÀrea Metropolitana de Barcelona.

Gutiérrez, A. (2008), El mètode URBAN i la seva difusió com a valor afegit de la iniciativa comunitària. In J. M. Llop et al. (eds.), Ciutats en (Re)construcció: Necessitats Socials i Millora de Barris, Barcelona, Diputació de Barcelona, pp. 303-325.

Gutiérrez, A. (2009), La Unió Europea i la Regeneració de Barris amb Dificultats. LAcció de la Iniciativa Comunitària URBAN i la Construcció duna Política Urbana Comunitària, Lleida, Universitat de Lleida.

Harvey, D. (1973), Social Justice and the City, London, Edward Arnold.

Indovina, F. (1992), La città possibile. In F. Indovina (ed.), La Città di Fine Millennio, Milan, Franco Angeli, pp. 11-76.

Leal, J. and Dominguez, M. (2008), Transformaciones económicas y segregación social en Madrid. Ciudad y Territorio. Estudios Territoriales, 157, pp. 703-725.

Llop, J. M. et al. (eds.) (2008), Ciutats en (Re)construcció: Necessitats Socials i Millora de Barris, Barcelona, Diputació de Barcelona.

López, J. and Rey, A. (2008), Inmigración y Segregación en las Áreas Metropolitanas Españolas: la Distribución Territorial de la Población no Europea en el Territorio (2001-2006), Barcelona, Institut dEstudis Territorials (Working Paper, 35).

Mier, M. J. et al. (2009a), Quatre anys daplicació de la Llei de Barris. In O. Nel lo (dir.), La Llei de Barris. Una Aposta Col·lectiva per la Cohesió Social, Barcelona, Generalitat de Catalunya, pp. 33-58.

Mier, M. J. et al. (2009b), La cooperació: la xarxa de barris amb projectes i la projecció internacional del programa de barris. In O. Nel·lo (dir.) , La Llei de Barris. Una Aposta Col·lectiva per a la Cohesió Social, Barcelona, Generalitat de Catalunya, pp. 132-138.

Mucchielli, L. (2007), Les émeutes de novembre 2005: les raisons de la colère. In L. Muchielli and V. Le Goaziou, Quand les banlieues brûlent. Retour sur les émeutes de novembre 2005, Paris, La Découverte, pp. 11-35.

Muñoz, F. (2004), UrBANALització. La Producció Residencial de Baixa Densitat a la Província de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Doctoral thesis, 3 volumes.

Muñoz, F. (2006), Fer ciutat, construir territori. La Llei de barris. Activitat Parlamentària, 8-9, pp. 59-75.

Muñoz, F. et al. (2009), La Llei de barris i la revitalització urbana. Els efectes sobre la construcció i la rehabilitació dhabitatges. In O. Nel lo (dir.), La Llei de Barris. Una Aposta Col·lectiva per a la Cohesió Social, Barcelona, Generalitat de Catalunya, pp. 83-104.

Nadal, J. (2007), Compareixença davant la Comissió de Política Territorial del Parlament de Catalunya, Barcelona, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Nel·lo, O. (2004), ¿Cambio de siglo, cambio de ciclo? Las grandes ciudades españolas en el umbral del siglo XXI. Ciudad y Territorio. Estudios Territoriales, xxxvi (141-142), pp. 523-542.

Nel·lo, O. (2005), La nuova politica territoriale della Catalogna. Archivio di Studi Urbani e Regionali, xxxvi (83), pp. 39-70.

Nel·lo, O. (2008), Contra la segregación urbana y por la cohesión social. La Ley de Barrios de Catalunya. Cidades. Comunidades e Territorios, 17, pp. 33-46. [ Links ]

Nel·lo, O. (dir.) (2009), La Llei de Barris. Una Aposta Col·lectiva per la Cohesió Social, Barcelona, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Parkinson, M. (1998), Combating Social Exclusion. Lessons from Area-Based Programmes in Europe, Bristol, Policy Press.

Pérez Quintana, V. and Sanchez Leon, P. (eds.) (2008), Memoria Ciudadana y Movimiento Vecinal, Madrid, 1969-2008, Madrid, Libros de la Catarata.

Picorelli, P. and Saborit, V. (2009), La inversió pública induïda per laplicació del programa de barris. In O. Nel lo (dir.) (2009), La Llei de Barris. Una Aposta Col·lectiva per la Cohesió Social, Barcelona, Generalitat de Catalunya, pp. 76-82.

Picorelli, P. et al. (2009), La renovació del parc residencial i els processos de remodelació urbana en el marc de la Llei de Barris. In O. Nel lo (dir.), La Llei de Barris. Una Aposta Col·lectiva per la Cohesió Social, Barcelona, Generalitat de Catalunya, pp. 105-114.

Smith, N. (2006), Gentrification generalized: from local anomaly to urban regeneration as global urban strategy. In M. Fisher and G. S. Y Downey (eds.), Frontiers of Capital. Ethnographic Reflections on the New Economy, Durham, Duke University Press, pp. 191-208.

Trilla, C. (2002), Preu dhabitatge i Segregació Social a Barcelona, Barcelona, Patronat Municipal dHabitatge.

Van Den Berg, L. et al. (eds.) (2007), National Policy Responses to Urban Challenges in Europe, Aldershot, Ashgate.

Notes

1 According to the Spanish Constitution and its Statute of Autonomy, Catalonia has exclusive competences in terms of urban and spatial planning. This ascription of competences also includes urban renewal policies. The full text of the Ley de mejora de barrios, áreas urbanas y villas que requieren atención especial can be found in Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 4151, June 10, 2004.

2 Data and statistical information used here were compiled for the studies carried out in 2009 evaluating this Law and its impact four years on from its enactment. These studies and all statistical evidence are found in Nel·lo (2009).

3 David Harvey (1973) wrote a classic text on the mechanisms involved in urban segregation processes and their results. In the case of the metropolitan area of Barcelona, the economist Carme Trilla (2002) and the geographer Francesc Muñoz (2004) quantified the capacity of different social groups to choose their residence comparing the average income of the population in each municipality and the respective average housing prices.

4 According to the survey compiled every year by the Catalan Government Environment and Housing Department, Housing Secretary, in 2007 households with income equalling 3.5 times the minimum wage would have to allocate more than 123% of their income to afford a new home in Barcelona; almost 90% in the metropolitan area of Barcelona, and 66% in the rest of Catalonia (Secretaria dHabitatge [2009] Informe sobre el sector de lhabitatge a Catalunya 2008, Barcelona, Departament de Medi Ambient i Habitatge).

5 For further insight on the objectives and the potential of the Law on neighbourhoods, see Muñoz (2006), Albors (2008) and Nel·lo (2009). In order to place this Law within the context of renewing the spatial management tools in Catalonia, see Nadal (2007) and Nel·lo (2005). In order to compare the experience with national experiences in other EU member countries, see Van den Berg et al. (2007).

6 As to the URBAN mode and its methodology, which is termed the urban acquis, see Gutierrez (2008 and 2009).

7 See, for example, in relation to the French case, Mucchielli (2007).

8 The 16 indicators, grouped by fields, are the following: (a) Urban regression processes, under-provision of equipment and services (registered values, poor state of building conservation, buildings without water or sewage services, four-story housing buildings without elevators); (b) demographic density (population density, excessively rising or falling population levels, rates of dependence, levels of immigration); (c) economic, social or environmental problems (number of citizens receiving government aid and fully government-funded pensions, high unemployment rates, lack of green areas, low levels of education, social and urban deficits; (d) local development problems (lack of public transportation, lack of parking places, low levels of business activities, percentage of citizens at risk of social exclusion). See decree 369/2004, de 7 de septiembre, por el que se desarrolla la Ley 2/2004, de 4 de junio, de mejora de barrios, áreas urbanas y villas que requieren atención especial (Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 4215, de 9 de septiembre 2004).

9 For data pertaining to the evolution of these complementary programmes in the period between 2004 and 2008, see Amill et al. (2009).

10 For a detailed analysis by field of investment under the auspices of this law, please refer to Mier et al. (2009a).

11 Estimates come from the data provided by municipalities in charge of programme implementation for the first semester of 2008. Hence, it is possible that some municipalities may not have taken into account all of the total resources mobilised and, therefore, investment is probably underestimated.

12 For a critical vision on the relationship between urban renewal policies and gentrification please refer to Smith (2006).

13 This measure was finally established by the Law - Ley 10/2004, de 24 de diciembre, de modificación de la Ley 2/2002, del 14 de marzo, de urbanismo, para el fomento de la vivienda asequible, la sostenibilidad territorial y la autonomía local. El Decreto ley 1/2007, de medidas urgentes en materia urbanística heightened the obligation to allocate around 40% of new housing funds for protected housing in municipalities with more than 10,000 citizens and, in comarca (district) capitals, up to 30%. These allocations are to be distributed between different modalities of protected and combined housing, and balanced out across the whole of the city. For further details on the relationship between the Law on neighbourhoods and Catalonian housing policies, see the work of Nel·lo (2008).

14 The call for projects is made at the beginning of each year, as the new budget is approved by the Parliament of Catalonia. The resolution to allocate sums, proposed by the Fund Management Commission is made at the end of the second quarter. At this time, city councils receive a notification and are to prepare the economic and financial programme and to sign the agreement with the regional government. These necessary procedures take up, as we have seen, the greater part of the first year.

15 As to the appearance of neighbourhood movements in the major Spanish cities during the final decades of Francos dictatorship, see the works by Borja (1986) and Castells (1983). As to its evolution in the last 40 years, see Domingo and Bonet (1998) and Pérez Quintana and Sánchez León (2008).

16 In particular, the role of the provincial Barcelona Diputación, which, in the five first calls, supported 35 municipalities in the design of their respective intervention projects.

17 The Law on neighbourhoods website, with the bulletin, the catalogue of good practices, and the programmed activities can be found at http://ecatalunya.gencat.net/portal/faces/public/barris.

18 CIVITAS Working Group; CIVITAS. A regional approach: added value for urban regeneration. URBACT Programme, Barcelona. (104 pp.) This document is found at: http://urbact.eu/projects/civitas/documents.html, with project content at: http://urbact.eu/projects/civitas/home.html

19 See Nel·lo (2009). This work also contains a file with the essential features and the budget for each of the 92 neighbourhood programmes included in the five call programmes. The volume includes as well the following evaluation reports: (a) Impact of the Law of neighbourhoods on both the activities and budgets of the Catalonia public administration; (b) social incidence of the Laws application; (c) programme impact on the building and renewal of housing; (d) effects on the transversal nature of policies and administrative organisation; (e) international profile of the programme; (f) evaluation of induced public investment; (g) programme relationship with other urban renewal processes; (h) cooperation and dissemination of experience mechanisms.