Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.226 Lisboa mar. 2018

https://doi.org/10.31447/AS00032573.2018226.01

ARTIGOS

The “sad grandmother”, the “simple but honest Portuguese,” and the “good son of the Fatherland”: letters of denunciation in the final decade of the Salazar regime.

A “avó triste”, o “Português simples mas honesto”, e o “bom filho da Pátria”: cartas de denúncia na década final do regime de Salazar.

Duncan Simpson*

*Instituto de História Contemporânea, FCSH, Universidade Nova de Lisboa Avenida de Berna, 26-C-1069-061, Lisboa, Portugal. duncan.a.simpson@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The “sad grandmother”, the “simple but honest Portuguese,” and the “good son of the Fatherland”: letters of denunciation in the final decade of the Salazar regime. Under the Salazar regime many Portuguese citizens wrote spontaneous letters of denunciation to the authorities. The phenomenon has been overlooked by historians of the Estado Novo. This article discusses a particular set of denunciation letters written during the final decade of the regime, held in a single file at the PIDE Archives (ANTT). It establishes a typology of denunciations and evaluates the role of social self-policing in the Estado Novo. It argues that society's relationship with the secret police was multi-faceted and not reducible to the status of “passive victim” commonly ascribed to it.

Keywords: secret police; letters of denunciation; accusatory practices; self-policing.

RESUMO

A “avó triste”, o “Português simples mas honesto”, e o “bom filho da Pátria”: cartas de denúncia na década final do regime de Salazar. Durante o regime de Salazar muitos cidadãos portugueses escreveram cartas espontâneas de denúncia às autoridades. Este é um fenómeno que tem sido ignorado pelos historiadores do Estado Novo. Este artigo aborda um conjunto particular de cartas de denúncia escritas durante a década final do regime e que se encontram reunidas num único ficheiro dos Arquivos da PIDE (ANTT). Estabelece uma tipologia destas denúncias e analisa o papel do autopoliciamento social durante o Estado Novo. Defende que a relação da sociedade com a polícia secreta era multifacetada e não redutível ao papel de “vítima passiva” que lhe é vulgarmente atribuído.

Palavras-chave: polícia secreta; cartas de denúncia; práticas acusatórias; autopoliciamento.

INTRODUCTION

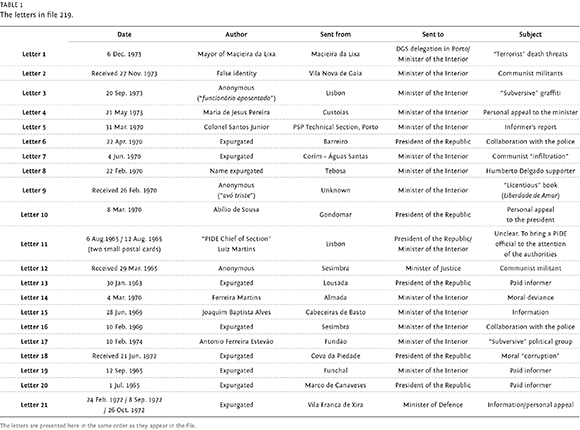

The archival corpus providing the empirical basis for this article is a sample of 21 letters written by Portuguese citizens to the authorities of the Estado Novo between 1963 and 1974. Most are spontaneous letters of denunciation, written by members of the public to draw the attention of the authorities toward a specific individual, group, or situation presented as deviant. They are contained in a single file kept in the PIDE Archives, at the Portuguese National Archives (ANTT). The file reference is: PIDE/DGS, SC, CI (1) 219, NT 1177, pasta 4. For the sake of simplicity, it will be referred to hereafter as file 219. Most of the letters in file 219 were addressed originally to the minister of the Interior. Some were sent to the president of the Republic and to the ministers of Justice and Defense. Upon reception, all of the letters were passed on by their original addressees to the secret police. The reason why they were assembled in this single file is not known.

As far as the present state of knowledge of the PIDE Archives allows us to conclude, file 219 is unique. Letters of denunciation are usually found scattered among the multitude of PIDE processos and dispersed across the different services of the secret police. “Letters of denunciation” was not a filing category for PIDE officials. The fact that the PIDE was not the only recipient of the letters of denunciation – perhaps not even its main one – merely adds to the dispersive effect. This means that the detection of these letters is an arduous, time-consuming exercise for the researcher. From this point of view, file 219 provides a unique opportunity for the exploratory analysis of “accusatory practices” (Gellately and Fitzpatrick, 1997) as a social phenomenon in Portugal during the Salazar dictatorship.

Although there is a unity of time in file 219, which covers the final decade of the Estado Novo, the diminutive size of the sample of denunciation letters provided by it, combined with the fact that the reason for its existence is unknown, means that it can offer only a fragmentary image of the phenomenon at the national scale.[1] This does not mean that the sample cannot be useful as a point of access to some of the practical, empirically observable aspects in the dynamics of accusatory practices in Salazar's Portugal. But it does mean that any attempt to generalize and to draw from file 219 any wider implications at the national level will have to be done tentatively, in the knowledge that further research, carried out on a much more substantial quantitative scale, will be necessary to confirm or infirm some of the interpretations attempted in this article.

This article has two main objectives: to provide a more detailed empirical analysis of spontaneous denunciations than the broad characterizations available in the literature of the subject area today; to place the analysis of denunciation letters within the broader framework of interrelations between Portuguese society and the repressive apparatus of the Estado Novo, in particular its secret police (PIDE/DGS[2]. The scholarly studies dedicated exclusively to the secret police in the Salazar dictatorship are noticeable for their rarity. According to the dominant interpretation in the field, the secret police served essentially two purposes: to repress, forcefully but selectively, any political opposition to the regime; to prevent any such opposition from emerging in the first place by spreading a dissuasive climate of fear in society (Ribeiro, 1995, p. 273; Pimentel, 2007, p. 535).[3]Notwithstanding the effects of Portuguese historiography's “hot summer” of 2012, which saw rival ideological clans clash over Rui Ramos's attempt to relativize the level of repressive violence exercised by the regime (Ramos, 2009, pp. 650-653)[4], the secret police's repressive impact on society – which included the persecution of oppositionists by means of arbitrary arrest, torture and internment – has been heavily emphasized by historians in the subject area (Madeira, 2007; Pimentel, 2007; Rosas et al., 2009; Rosas, 2012, pp. 190-210). Combined with the continuing prevalence of references to an ill-defined state of “generalized fear” gripping Portuguese society under Salazar – the alleged result of rumor, “exemplary” cases of PIDE brutality, and a generalized belief in the existence of a network of PIDE informers reaching into every recess of society – the result of the emphasis placed on the high level of political violence exercised selectively by the regime against the few who attempted to oppose it has been to relegate the bulk of the population to the status of “passive victims” of the dictatorship's repressive apparatus. Consequently, the dominant interpretative framework has tended to limit the interrelations between society and the regime's repressive apparatus to a dichotomist opposition between violent repression (or the threat of it) on one side, and “passive victims paralyzed by fear” on the other. While the existence of a “culture of denunciation” among the population has been pointed out, it has been interpreted mainly in three ways: as the Portuguese reality of a broader phenomenon that “tarnished the Twentieth Century”, as the unfortunate side-effect of a regime that encouraged that kind of behavior, and as the consequence of Portugal's societal traits as a small, warm-climate country, where people gathered in public spaces and tended to “speak easily” (Delgado, 1998, p. 221; Pimentel, 2007, p. 314).

This article argues that society's relationship with the PIDE was multi-faceted, and not reducible to the role of “passive victim”. Rather it has to be apprehended through a broader analytical prism, capable of reflecting the interactive character of the interrelations between society and the regime's repressive apparatus. Drawing upon the international bibliography on accusatory practices in other Twentieth Century European dictatorial regimes, this article argues that letters of spontaneous denunciations have much to reveal about the way Portuguese society responded to the realities of the Estado Novo as a political system, and about the internal dynamics of the system itself. For some Portuguese citizens – not necessarily supporters of the regime, but rather members of the “depoliticized masses” –, the PIDE could be manipulated from below into acting on their behalf. For others, it was an institution that could be collaborated with, to contain the risk of communist “subversion” or to fight the “moral deliquescence” associated with modern societal trends. For the poor, it could come to be seen as an economic opportunity in the struggle against grinding poverty.

To say this does not mean ignoring the negative nature of the secret police's function under the Estado Novo. The terrible arbitrariness of its rule and the devastating violence of its methods must be kept at the forefront of the nation's collective memory – as indeed they have been. But this does not preclude from studying its interrelation with society in its full complexity. Over the course of more than four decades, for many Portuguese citizens the Salazarist system was normalized as part of the structure of everyday life. Society adapted to the institutional framework imposed by the dictatorial regime – including the secret police – acting on the opportunities that opened up rather than remaining dependent or passive. To recognize this means restoring society to a more active role, and to a measure of responsibility, in the control of its destiny. It also means looking at Portuguese society under Salazar as it effectively existed and functioned, rather than as one might have preferred it to exist and function.

The article begins with a typology of the denunciation letters in file 219, focusing on their signification for the nature of the interaction between society and the authorities, in particular the secret police. They can be classified into three distinct groups: those written manipulatively in the pursuit of a personal agenda; those whose authors denounced the political deviance of a particular individual or group from the established norm; those whose authors denounced the moral deviance of a particular individual or group from the established norm.

PERSONAL AGENDA LETTERS

In 1951, Joaquim Trigo de Negreiros, the minister of the Interior – under whose tutelage the secret police was placed – lamented what looked like a veritable epidemic of denunciation letters sent by members of the public (Pimentel, 2007, p. 74). For many Portuguese citizens, the PIDE appeared to be an institution that could be manipulated from below into acting on their behalf, rather than an agent of persecution to be feared.

Identifying the letters written manipulatively in the pursuit of a personal agenda – usually by getting the regime's repressive apparatus to act against a third party – is not a straightforward task. The authors of these letters were careful to present their denunciations under a cloak of verisimilitude. They posed as well intentioned nationalists acting out of a sense of loyalty to the regime, they used the expected formulae in their letters (‘A bem da Nação'[5] was an almost obligatory closing salutation), and they used false identities rather than send anonymous letters, in order to add the appearance of veracity to their denunciations.[6] It is precisely the artificially formatted character of these letters, along with the incongruities they often contained, that allow their manipulative intent to be detected. In file 219, eight letters can be said with reasonable certainty to have been written with manipulative intent. They represent over one third of the letters in the file.

The nature of the personal agendas pursued by their authors, which in file 219 can only be tentatively guessed at, was extremely diverse. In letter 2, sent from Vila Nova de Gaia to the minister of the Interior (César Moreira Baptista) on 27 November 1973, the personal agenda appeared to be rooted in local politics, possibly to get an influential local personality into some kind of trouble with the authorities. The author accused a certain “Manuel Casais” of operating a communist cell in the city, whose plans, in addition to helping “deserters” from the army to emigrate abroad clandestinely – to escape the unending colonial wars[7] – included killing Marcello Caetano, the minister of the Interior and the minister of Defense (file 219, p. 11). The extravagant nature of these accusations, which look like a catalogue of the crimes most likely to provoke the authorities into action, is a first indication of the spurious nature of the accusations. This impression is confirmed by the nature of the “proof of veracity” invoked by the author to support his accusation, namely the fact that Casais had attempted to enlist him into his group with promises of material goods, such as money and a car. This would have been a highly unlikely recruiting practice in the underground communist movement, whose methods were carefully designed to ensure the ideological commitment of their recruits (Godinho, 1998, pp. 328-337). Upon being forwarded the letter by the ministry of the Interior, the DGS proceeded to investigate the case. It found that the same letter had been sent to its services a few weeks earlier, this time signed by a certain “Maria Fernanda”, whom “it had also been impossible to identify”. Eventually, the DGS identified the “accused”, who was in fact a locally elected figure found to be loyal to the regime (file 219, p. 14).

Most of the personal agenda letters played the “red threat” card to set the authorities into action, suggesting that the regime's anti-communist propaganda had impacted heavily on Portuguese society. Letter 7, sent on 4 June 1970 by a Corim-Águas Santas resident to the minister of the Interior (António Gonçalves Rapazote), was probably designed by its author to gain an advantage in the law courts, or to prevent a third party from doing so. In it the author accused a local lawyer of perverting the course of justice by doctoring the witnesses in an on-going court case, and called upon the secret police to “find” and interrogate him (file 219, p. 37). In this case it is the artificially formatted character of the letter – the nationalist allegiance of the author, the self-deprecating stance (he referred to himself as a “simple but honest Portuguese”), the out-of-place anti-communist diatribe – that suggest a fabricated accusation. The same palpably formatted character was apparent in letter 12, sent to the minister of Justice (João Antunes Varela) by a Sesimbra resident on 29 March 1965. On this occasion the personal agenda seemed to be to damage a business competitor. In it the author, who signed off as a “functionary of the PIDE”, accused a salesman in Leiria of “belong[ing] to the Portuguese Communist Party”, calling for his “immediate arrest” (file 219, p. 59).

The loosely defined communist menace could also be appropriated by individual members of the public to victimize themselves before the authorities with the aim of furthering a personal objective. On 8 March 1970, Abílio de Sousa, from Gondomar, wrote to the president of the Republic (Américo Thomaz) with this objective in mind (letter 10). In the letter he portrayed himself as the victim of “terrorism”, an expression which in the context of the time was a straightforward reference to the actions of radical left-wing groups and armed-struggle organizations operating in Portugal (such as the ARA and LUAR). To escape this “threat”, he planned to emigrate to the United States, calling upon Thomaz's assistance to facilitate his exit from Portugal (file 219, pp. 44-45). Somewhat predictably, the stratagem failed. The letter was forwarded to the secret police, and Abílio de Sousa duly advised to follow the administrative requirements necessary “for his journey abroad as an emigrant” (file 219, p. 43). A similar strategy was resorted to by a Vila Franca de Xira resident in a series of three letters addressed to the minister of Defence (Horácio Viana Rebelo) between February and October 1972 (letter 21, file 219, pp. 109-118). The author described himself as the victim of persecution at the hands of the Jehovah's Witnesses movement – “which is Communism, according to what they say [sic]” – and asked for some form of support from the minister (possibly financial) for himself and his family (file 219, p. 109). However ideologically confused the author of the letter may have been – which indicated that he probably belonged to the “depoliticized masses” – he had grasped that the main ideological enemy of the regime was communism, and that by presenting himself as its victim, the authorities may be put to work toward his personal agenda.

Not all personal agenda letters played the “red threat” card, however. This was the case of the letters designed to draw the attention of the authorities on a specific individual without attempting to provide a good (or any) reason for doing so. Two letters in file 219 can be read in this light. In the case of letter 11 (in fact two small post cards), written in August 1965, the content was so outrageous and nonsensical that it seemed to have been written with no other purpose than to direct the authorities' attention toward the person under whose name they were signed – in this case the “PIDE Chief of Section Luiz Martins”, whose address was given as the prison wing in the Júlio de Matos psychiatric hospital in Lisbon (file 219, p. 50-52). Letter 15 was signed under the name of Joaquim Baptista Alves and sent from Cabeceiras de Basto to the minister of the Interior (António Gonçalves Rapazote) on 28 June 1969. In it the author asked “for the visit of a PIDE agent to [his] house” in order to “pass on to Your Excellency some information that will need to be clarified” (file 219, p. 83). Such a request was not impossible, but unlikely. As a norm, contact with the police, and with the PIDE in particular, was carried out discretely. If for paid informers, the need for discretion was obvious, few were the individuals for whom open association with the police could be profitable (Riegelhaupt, 1979, p. 514). It is possible that letter 15 was written by a third party in pursuit of a personal agenda, in this case, judging by the address given (the “Quinta do Ribeiro”), perhaps to put an influential local figure into uncomfortable contact with the “authorities”.

The number and diversity of the personal agenda letters in file 219 suggest the importance of spontaneous denunciations as instruments of authoritarian control over society. They provided the PIDE with cases to investigate, they fueled the population's belief that the PIDE's panoptic eyes were watching them, and consequently they contributed to the realization of the Estado Novo's “optimal coefficient of terror”. There is little doubt that, as has commonly been emphasized, many of the personal agenda letters were written for petty reasons – out of rivalry and envy, to “solve” a personal dispute – and could reflect classist or economic interests. As in other dictatorial regimes, the Estado Novo's institutional set-up provided many Portuguese with the opportunity to exercise some form of personal malice. But the meaning of the letters should not be reduced to that. Fundamentally, they also gave citizens a measure of control over the political system. They showed that the system could be – and indeed was – enticed from below into acting on the behalf of individual Portuguese citizens. There is no evidence to suggest that all personal agenda letters were systematically written with malicious intent. Faced with an unresponsive system, some of the authors of these letters may have turned to the secret police to have a “genuine” wrong righted, for example by trying to have a local figure or official duly investigated. Further research will be required to determine whether in Portugal the PIDE came to act as a “mediator of conflicts”, or even as a “substitute for usual channels of interest articulation” – as has written Robert Gellately about the Stasi in the GDR (Gellately, 1996, p. 963). The role occasionally played by the PIDE in signaling the abusive practices of some employers within the corporatist organization of the economy, to prevent potential sources of labor conflict from developing, suggests that this might have been the case.

As active manipulators of the system, the authors of the personal agenda letters belonged to a different category than the “passive victims” of the regime's repressive apparatus. But there was another group of Portuguese citizens who in their relationship with the PIDE were not only distinct from its “passive victims”, but their exact opposite: the Estado Novo's willing collaborators.

POLITICAL DEVIANCE LETTERS

The authors of the second category of letters identifiable in file 219 wrote their letters out of a sense of support for the Estado Novo – albeit with varying degrees of intensity and from different perspectives – to denounce any suspected forms of political opposition to it. Six letters in file 219 belong to this category. The total reaches eight if two of the personal agenda letters analyzed above, whose ultimate finality is open to reasonable doubt, are taken as “genuine” denunciations – namely letters 7 and 12, both rooted in a concern for the infiltration of communist ideals in Portuguese society. In file 219, the number of this category of letters is only slightly less than the number of personal agenda letters.

Several of the political deviance letters originated in their authors' concern for the increasingly adverse context in which the regime was forced to operate during its final decade of existence, both domestically and internationally. While personal agenda letters tended to be anonymous, the political deviance letters were usually signed by their authors. This was the case of letter 8, sent on 22 February 1970 by a 52 year-old inhabitant of Tebosa (Braga district) to the minister of the Interior. In it the author denounced the appointment of an allegedly well-known supporter of Humberto Delgado during the 1958 presidential election campaign (a certain José Ferreira Couto) to the local municipal council.[8] Indirectly he also accused the local mayor, “who nominated him” despite being aware of his adverse dispositions in relation to the regime's single party. The National Union, he argued, could not be expected “to defend itself” – as indeed was needed “today (…) more than ever” – while harboring “adversaries” in its ranks (file 219, p. 40). In the context of rising contestation against the regime, some willing collaborators were eager to make their collaboration with the authorities ever more efficient. On 22 April 1970 the author of letter 6, from Barreiro, wrote to the president of the Republic, asking for an official “authorization” to identify himself more easily as a loyal supporter of the regime when providing information to the police – in turn allowing the police to “put the detractors in order” as rapidly as possible (file 219, p. 34). For some willing collaborators, in the context of growing contestation against the regime, even the vaguest sign of dissident political activity had to be acted upon. Letter 17 was sent to the minister of the Interior on 10 February 1974 by a Fundão resident, Antonio Ferreira Estevão, a retired PSP guard in Angola. The author reported a conversation he had overheard in a taxi about a suspicious sounding organization (the “Revolução Popular Manuelina”), whose members, “individuals of the highest social class”, were preparing a meeting in Penafiel the following week. The implication was that his tip-off would allow the authorities to track down these individuals (file 219, p. 92). In the context of radicalization of the opposition to the Estado Novo in the early 1970s, other Portuguese citizens appealed to the secret police for protection. On 6 December 1973 the mayor of Macieira da Lixa sent a letter to the DGS delegation in Porto and to the minister of the Interior (letter 1). The small town of Macieira da Lixa was then at the center of national affairs, following the arrest of its parish priest (father Mário de Oliveira) for criticizing the regime's colonial policies from the pulpit. After receiving anonymous death threats in retaliation for his alleged role in the court case launched against the priest, the mayor called upon the secret police to investigate the case (forwarding to it the anonymous letter) and take the “security measures” necessary to ensure his protection from any potential act of “terrorism” (file 219, pp. 6-9).

One distinct sub-category in the political deviance letters included the letters whose authors denounced the insufficient degree of ideological commitment displayed by the lower echelons of the public administration, responsible for implementing the policies defined by the political “chiefs” at the top of the regime. Letter 6, mentioned in the previous paragraph, included a degree of indirect criticism of the police forces, for failing to act more swiftly on the information provided by well-meaning citizens against the “detractors” of the regime (file 219, p. 34). Similarly, on 20 September 1973, a “retired civil servant” from Lisbon wrote to the minister of the Interior to denounce the lack of ideological commitment displayed by the director of the Santa Maria Hospital in Lisbon (letter 3). He accused him of failing to have a “subversive” graffiti – attributed to the “lackeys of Moscow” – erased from the hospital walls, and the “traitor” responsible for it duly identified (file 219, pp. 16-17). Letter 14, written on 4 March 1970 by an Almada resident to the minister of the Interior, in support of the Government's campaign for the “repression of pornography” (which we will analyze more closely in the following sub-section), was also extremely critical of the perceived lack of commitment in ensuring the implementation of the campaign, displayed both by the police forces (namely the PSP) and the lower echelons of the administration, whose permissive “weakness” was allowing immoral behavior to prosper in the Portuguese capital. So as to prevent the denaturation of the Estado Novo, the author of the letter called upon the minister to take stringent measures against those in the ranks of the public administration who were failing to live up to the vision elaborated by the highest political authorities in the regime, in continuation of Salazar's “genius” (file 219, pp. 78-80). It is significant that these last two letters, which are the most virulent in the expression of their support for the regime and in their diatribes against its enemies, were written by ageing nationalists. The first made a telling reference to the “chaos of 1917 to 1926” (file 219, p. 17), the second referred in idealized terms to historical nationalists whose vigor he deemed to be sorely lacking in contemporary Portugal (file 219, p. 80). As such, even if the non-representative nature of the sample of denunciation letters in file 219 is duly taken into account, they can be interpreted as the symptoms of an increasingly obsolescent regime. The support base of the Estado Novo was shrinking and ageing. It seemed to be composed increasingly of individuals unable to envisage the loss of forward ideological thrust in the Estado Novo as anything other than an internal betrayal of its “chiefs” by an underperforming administration, whose “sanitization” they consequently called for. The two letters signaled also the increasingly anachronistic nature of the societal vision carried by the Estado Novo, whose timid openings to modern lifestyles were enough to trigger the reproaches of its ageing willing collaborators. This point was made even more clearly in the third category of denunciation letters in file 219.

MORAL DEVIANCE LETTERS

The third type of denunciation letters in file 219 was the one whose authors aimed to bring to the attention of the public authorities cases of moral deviance from the established norm under the Estado Novo. As in the case of the political deviance letters, the authors of the moral deviance letters were also willing collaborators of the regime's repressive apparatus – the exact opposite of its “passive victims”. In a society subjected to the effects of the persistent collaborative alliance between the Salazar regime and the Catholic Church, geared toward the realization of an idealized (and failed) program to “re-Christianize” the nation (Simpson, 2014), the established moral norms were to a large extent – although not exclusively – informed by Catholic principles of morality understood in their most conservative form. It is significant in this respect that the authors of the moral deviance letters frequently resorted to religious (Catholic) imagery.

For an ideologically driven dictatorship such as the Estado Novo, the set of values embodied by the regime could provide a platform for the collaborative interrelation between the members of the public and the authorities, including the secret police whose task it was to prevent and punish any such sign of moral deviance. Ferreira Martins, the author of letter 14, sent from Almada to the minister of the Interior on 4 March 1970, highlighted the point. He wrote his letter in the context of the ministry of the Interior's recently launched “repression of pornography” campaign, which he described as a “laudable” initiative. The official note published for the occasion by the ministry stated that “any individual interested in the defense of good morals will be able to collaborate [with the authorities] in the sanitization of the social environment by directing their complaints [i.e. denunciations] to the Direcção-Geral de Segurança or to the Judiciary Police”.[9] This rationalized statement of the mission of the secret police offered the opportunity for the public to take part in its realization. In the words of the author of letter 14, it “open[ed] up a door to the general confidence of the population so that it might collaborate, honestly and disinterestedly, with the Public Authorities in a campaign that (…) concerns all of us” (file 219, p. 78). His letter was written as part of this collaborative interrelation. In it, Ferreira Martins painted an apocalyptic picture of Portuguese society in 1970, one in which “pornography, prostitution, homosexualism [sic], and all other base and abject feelings, ha[d] developed appallingly” (file 219, p. 78). Modern trends such as the accession of women to the work place and the increasing liberality of the “boîtes” and “casinos” in the Portuguese capital were taken as signs of the “state of moral dissoluteness” which affected the nation in general, and its youth in particular. The author singled out for denunciation a specific establishment in Almada, the aptly named Toca da Raposa – veritable “den of vice and sin” – and called for its forcible closure “for the good of public morality” (file 219, p. 79). A similar lamentation about the state of moral deliquescence in Portugal was apparent in letter 9, sent to the minister of the Interior on 26 February 1970 by a “sad grandmother”. This time it was the sexual liberation of women that was lamented. The “sad grandmother” – who claimed “not to know” what pornography was – had caught her granddaughter reading a “disgusting” book, and decided to report it to the authorities. Entitled Liberdade de amar, its contents constituted in her view little more than a series of teachings for “the women of disreputable lifestyle”. The fact that it even existed, she concluded, “show[ed] what we have come to my God [sic]” (file 219, p. 42). The implicit meaning of the letter was that something should be done in order to prevent such books from being published and circulated. Finally in letter 18, sent to the president of the Republic by a Cova da Piedade resident on 21 June 1972, the author denounced a group of “undesirable individuals” engaged in a life of “corruption” and “prostitution” on the Cristo Rei avenue in Almada (file 219, p. 97). The letter could be taken as a straightforward case of public disorder, but the degree of moral judgment the author was eager to convey to the public authorities suggests that it was the commitment to certain values shared with the regime that provided the platform for collaboration between the author and the public authorities of the Estado Novo.

As was the case with the political deviance letters, the authors of the moral deviance letters appeared to be aged. The author of letter 14 made characteristic references to the early days in the life of the Estado Novo (file 219, pp. 79-80); the author of letter 9 was a grandmother. Although the non-representative nature of the sample of letters must be taken into account, it is surely significant to note that, out of the three types of letters identified in file 219, the moral deviance letters are the fewest. If one chooses to consider letter 18 as a mere case of public disorder, there are only two of them. This may be interpreted as a further sign of the cycle of decay that the regime was engaged in during the final years of its existence. So anachronistic had the set of ideological and moral values associated with the regime become, that it seemed to be able to mobilize only the support of an ever dwindling and ageing group of willing collaborators.

Most of the denunciation letters in file 219, as we have seen, were sent to the minister of the Interior and to the president of the Republic, in addition to the PIDE/DGS. In fact the authoritarian, unresponsive nature of the Estado Novo as a political system fostered all types of direct appeals to the representatives of “authority”. On 21 May 1973, Maria de Jesus Pereira, from Custoias, wrote directly to the minister of the Interior (letter 4). Born in Brazil, she had been brought up by relatives in Portugal from the age of two but had never been given any identity papers. Now aged, and anxious to avoid any problem for the “friendly family” that had taken her in (she was also poor), she set out to obtain some identity papers. To this end she wrote to the minister of the Interior, appealing to his “good heart” in the hope that he might facilitate the administrative process (file 219, pp. 24-25). The existence of such letters signaled the persistence among some parts of Portuguese society of a pre-modern relationship to authority, rooted in a patriarchal image of political power and patronage. Its persistence was the result of the imperfect deployment of the modern State (and the services associated with it) in some of the most rural recesses of early-1970s Portugal. The accompanying transformative impact on public attitudes, namely to authority, had consequently been realized only incompletely among part of the population in those areas. But it was also a consequence of the unresponsive nature of an authoritarian regime such as the Estado Novo for the common citizen. Appeals to the “good heart” of the prominent personalities in the regime could be continued to be viewed by the public as a viable alternative to contact with a State bureaucracy experienced as inefficient and unresponsive. THE IMPACT OF THE LETTERS: ASPECTS OF SELF-POLICING IN THE ESTADO NOVO

File 219 contains evidence that spontaneous letters of denunciation were taken seriously by the authorities and acted upon by the secret police. The fact that the letters were forwarded by their original addressees (mainly the minister of the Interior and the president of the Republic) to the secret police was a first indication of the importance given to them. That they were forwarded to the PIDE/DGS “for all ends judged convenient [by it]” not only reflected the huge margin of arbitrary maneuver afforded the secret police in the Estado Novo, but emphasized also the potentially serious consequences the letters could have. Of the six letters in file 219 that contained specific information about a suspicious individual, group, or situation – that is, information precise enough to be acted upon – there is evidence that the secret police activated some kind of investigative action in at least four cases.

Even the most trivial letter, whose author had given only the flimsiest evidence of credibility, was taken seriously. Upon receiving the letter written by the “sad grandmother” in February 1970, the secret police set about to find a copy of the licentious book Liberdade de Amar in the capital's bookshops. It was then dispatched to the censorship services “for appreciation and decision” (file 219, p. 41). Antonio Ferreira Estevão's vague references to the meeting of a potentially subversive group in Penafiel in February 1974 also gave rise to a full scale investigation by the secret police, in order to determine who these individuals were, and whether they presented a genuine threat to the regime. The DGS delegation in Porto was instructed to investigate all the events taking place in and around Penafiel at the date given by the author of the letter. As it turned out, according to the report sent to the DGS headquarters in Lisbon on 20 February 1974, the only two events held in the town had been the reunions of a monarchist group – described by the DGS as a harmless periodical occurrence – and the Rotary Club – which, “according to a reliable person, had not been political in character” (file 219, p. 95). As we have seen, in November 1973 the DGS also followed up on the denunciation of an alleged PCP militant in Vila Nova de Gaia, although the letter itself showed all the obvious features of a false accusation written for personal reasons (letter 2). According to the investigations carried out on the ground by the secret police, the “accused”, a certain Manuel Ferreira Casal, was in fact an elected official in the Oliveira do Douro municipal council, “considered in that locality to be aligned with the incumbent regime” (file 219, p. 14). In the case of the corruption and prostitution ring operated by a group of “undesirable individuals” in Almada (letter 19), the denunciation was also duly forwarded by the secret police to the PSP (file 219, p. 96) – reflecting the strong collaborative bond, not devoid of tensions, between the different police forces (PIDE/DGS, PSP, PJ, GNR). As for Maria de Jesus Pereira's appeal to the “good heart” of the minister of the Interior in May 1973, it ended up getting her referenced by the secret police, to which the minister had forwarded the letter “for all ends judged convenient” (file 219, p. 19). Writing to the authorities of a regime intent on securing its control over the population was not devoid of risk.

File 219 suggests that the PIDE/DGS valued the spontaneous letters of denunciation it received from the members of the public. It valued them primarily as a source of information for the immediate investigation of suspicious individuals, groups, or situations. But the fact that the letters were all carefully read and filed suggests that even the letters that offered no immediately useable information were valued as channels of communication from society at the ground level – whether on political, economic, or social affairs. The evidence in file 219 suggests also that social self-policing was considered by the authorities to have an important contribution to make to the action of the secret police in the accomplishment of its mission. The exact importance of the contribution made by self-policing remains to be determined in the case of Salazar's Portugal. It will require further sampling and in-depth treatment of the denunciation letters in order to uncover the precise scale of the phenomenon and its impact on the action of the PIDE – for example, by determining how many of the letters actually led to prosecutions by the secret police. Regimes marked by high police saturation, such as the Soviet regime under Stalin (NKVD) or the GDR in the 1980s (Stasi), tended to generate their own accusatory material, in the latter case putting the amateur denouncer out of business (Fitzpatrick, 1994, pp. 26-27). Regimes with (relatively) lower levels of police saturation tended to rely on denunciations more. This was the case of the Gestapo in Nazi Germany, particularly when the scope of its “mission” expanded dramatically during the course of the Second World War (Gellately, 1990, pp. 259-261; Johnson, 2000, p. 21). In the case of the Portuguese Estado Novo – notwithstanding the fundamental differences between its conservative authoritarianism and the totalitarian dynamic of the regimes mentioned above – it is possible that a similar, increased reliance on the spontaneous denunciations from members of the public occurred in the final years of the regime. The DGS, which, despite some improvement, remained under-equipped and poorly trained until the very end (Pimentel, 2007, pp. 59-60), probably needed the cooperation of Portuguese society more to accomplish its mission in a context marked by the multiplication and radicalization of the opposition's initiatives against the regime.

THE SECRET POLICE AS ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY FOR THE POOR

The PIDE/DGS operated a vast network of paid informers (20,000 in 1974 according to the Commission for the Extinction of the PIDE/DGS). Each informer was placed under the responsibility of the agent who recruited him (or her), and paid according to the quantity and quality of the information provided. Informers were usually paid a monthly salary, whereas the lesser “occasional collaborators” received payment for information as it was delivered (Pimentel, 2007, p. 318). File 219 included the report of one such informer in Porto (about internal dissentions among Catholics in 1970), reflecting the importance of this paid network for the police (letter 5, file 219, pp. 31-32). Members of the public sometimes spontaneously applied for a position as paid informer. In a number of cases, the candidates were turned down by the PIDE, for lack of the required profile. Letter 16 probably belongs to this category. It was sent by a Sesimbra resident to the minister of the Interior on 10 February 1969. It is difficult to read, due partly to the author's untrained handwriting, and partly to the extreme confusion of its contents. Among other things the author demanded a special “card” and “list” from the PIDE to “defend the Fatherland”. A hand written note on the top left corner of the letter, jotted down by a PIDE official upon reception, described the author as “mentally ill” (file 219, pp. 89-90). The case was representative of the inconsistent nature of the spontaneous letters sent by the members of the public to the secret police. They were frequently unreliable. Reading them, and dealing with them, could be a time consuming affair for the secret police agents – often, as in this particular case, for no benefit at all. File 219 also includes three letters sent by members of the public as clearly identified “spontaneous applications” to the position of paid informer for the secret police (Several more of such letters seemed to have been included originally in file 219, but were subsequently archived in the Informers Section of the DGS, file 219, p. 1). They represented the culminating point in collaborative interaction between society and the PIDE. For this reason, they deserve a reference in this article.

The most striking feature in these letters, all written between 1963 and 1965, was their homogeneity in terms of both form and content. All three candidates started by trying to emphasise their ideological commitment to the regime. The first would-be informer, writing to the president of the Republic and the minister of the Interior from Lousada on 30 January 1963, portrayed himself as a “good son of the Fatherland” (letter 13, file 219, p. 62-65). The second, writing from Funchal (Madeira) to the minister of the Interior (Alfredo Santos Júnior) on 12 September 1965, stated his resolve to “assist the PIDE for the good of the Nation” (letter 19, file 219, p. 101). The third, writing from Marco de Canaveses to the president of the Republic on 1 July 1965, put forward his eagerness to “arrest those who sp[oke] against the government” (letter 20, file 219, pp. 105-106). The rudimentary nature of these pledges of allegiance to the regime meant that they came across as little more than a formal obligation for their authors. The impression is confirmed by the fact that each of the three would-be informers then proceeded to put forward a far more pressing reason for their “spontaneous applications”: the destitute social and material position they found themselves in. The candidate from Marco de Canaveses presented himself as “poor but sincere” (file 219, p. 105); the one from Lousada portrayed himself as “living off the charity of those who pitied [him]” and appealed to the minister as a “friend of the poor” (file 219, p. 62); the candidate from Funchal described himself as a “pequeno a Nalfabético[10] [sic]” (file 219, p. 101).The poor quality of the syntax, grammar, and lexical range displayed by the authors in each of the letters made clear that this was no mere posturing designed to encourage the generosity of their addressees – one candidate did appeal to the “good heart” of Américo Thomaz (file 219, p. 65) – but rather the reflection of their low cultural capital and socio-economic status.

Notwithstanding the limitations of the letter sample in file 219, two interpretative conclusions – which will need to be researched further – can be drawn from it concerning the “spontaneous applications” to act as paid informer for the PIDE. The first is that these “spontaneous applications”, in the final years of Salazar's rule, seemed to be moved more from material necessity than a sense of ideological commitment to the regime. That the commitment to the Estado Novo was claimed by each of the authors of the letters should be seen rather as a further indication of their capacity to adapt to the regime to make it work toward their personal agendas – in this case the attribution of an income by the secret police. The second is that these letters of “spontaneous application” to the PIDE provide an indication that for some among the poorest in society – probably a non-negligible amount[11] – the status of “passive victims” of the secret police was not the category under which they envisaged themselves. As far as they were concerned, the PIDE was not a threat to their “freedom” and to their “well-being”, which were severely restricted by their material conditions anyway. Rather, it was considered potentially as a paternalistic sponsor that might support them in their struggle against social misery, a State institution susceptible of being made to work toward the resolution of their most urgent necessities. The PIDE was – or had become – an economic opportunity in a society tragically short of them.

REFERENCES

CEREZALES, D. P. (2011), Portugal à Coronhada. Protesto Popular e Ordem Pública nos séculos XIX e XX, Lisbon, Tinta-da-China. [ Links ]

CEREZALES, D. P. (2015), “Polícia e represión en la dictadura portuguesa, 1926-1974”. In J. Marco, J. Mansan, H. Silveira (eds.), Violência e Sociedade em Ditaduras Ibero-americanas no Século XX: Argentina, Brasil, Espanha e Portugal, Portoalegre, EDIPUCRS, pp. 163-183. [ Links ]

DELGADO, I. (1998), “A PIDE. O Império da Vigilância”. In I. Delgado, C. Pacheco, T. Faria (eds.), Humberto Delgado. As Eleições de 58, Lisbon, Vega, pp. 215-224. [ Links ]

FITZPATRICK, S. (1994), “Signals from below: Soviet letters of denunciation of the 1930s”. The National Council for Soviet and East European Research. The Practice of Denunciation in Stalinist Russia, vol. 1, Washington, DC, National Council for Soviet and East European Research, pp. 1-27. [ Links ]

GALLAGHER, T. (1979), “Controlled repression in Salazar's Portugal”. Journal of Contemporary History, 14, pp. 385-402. [ Links ]

GELLATELY, R. (1990), The Gestapo and German Society. Enforcing Racial Policy 1933-1945, Oxford, Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

GELLATELY, R. (1996), “Denunciations in Twentieth century Germany: aspects of self-policing in the Third Reich and the German Democratic Republic”. Journal of Modern History, 68, pp. 931-967. [ Links ]

GELLATELY, R., FITZPATRICK, S. (eds.) (1997), Accusatory Practices. Denunciation in Modern European History, 1789-1989, Chicago, Chicago University Press. [ Links ]

GIESEKE, J. (2014), “The Stasi and East German society: some remarks on current research”. GHI Bulletin Supplement, 9, pp. 59-72. [ Links ]

GIESEKE, J. (2015), The History of the Stasi. East Germany's Secret Police, 1945-1990, New York and Oxford, Berghahn Books [ Links ]

GODINHO, P. (1998), Memórias da Resistência Rural no Sul. Couço (1958-1962). Doctoral dissertation, Lisbon, FCSH, Universidade Nova [ Links ]

JOHNSON, E. (2000), Nazi Terror. The Gestapo, Jews, and Ordinary Germans, New York, Basic Books [ Links ]

MADEIRA, J. (ed.) (2007), Vítimas de Salazar. Estado Novo e Violência Politica, Lisbon, Esfera dos Livros. [ Links ]

MARTINS, H. (1998), Classe, Status e Poder, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

PIMENTEL, I. F. (2007), A História da PIDE, Rio de Mouro, Círculo de Leitores. [ Links ]

PIMENTEL, I. F. (2011), “A polícia política do Estado Novo Português – PIDE/DGS. História, Justiça e Memória”. Acervo, 24 (1), pp. 139-156 [ Links ]

PITTAWAY, M. (2004), “Control and consent in Eastern Europe's Workers' States, 1945-1989: some reflections on totalitarianism, social organization, and social control”. In C. Emsley, E. Johnson, P. Spierenburg (eds.), Social Control in Europe 1800-2000, vol. 2, Columbus, The Ohio State University Press, pp. 343-367. [ Links ]

RAMOS, R. (ed.) (2009), História de Portugal, Lisbon, Esfera dos Livros. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, M. C. (1995), A Polícia Política no Estado Novo 1926-1945, Lisbon, Editorial Estampa. [ Links ]

RIEGELHAUPT, J. (1979), “Os camponeses e a política no Portugal de Salazar. O Estado corporativo e o ‘apoliticismo' nas aldeias”. Análise Social, 59, XV (3.º), pp. 505-523. [ Links ]

ROSAS, F., et al. (2009), Tribunais Políticos. Tribunais Militares Especiais e Tribunais Plenários durante a Ditadura e o Estado Novo, Lisbon, Temas e Debates. [ Links ]

ROSAS, F. (2012), Salazar e o Poder, Lisbon, Tinta-da-China. [ Links ] [ Links ]

Received at 30-06-2017. Accepted for publication 08-01-2018.

[1]The diminutive size of the sample in file 219 should not be taken as evidence of the limited scale of the phenomenon of denunciation letters during the Estado Novo. On the contrary, so widespread had the trend become by the 1950s that the minister of the Interior felt compelled to lament it, since it contradicted the propaganda claims of an organically harmonious society realized in the corporatist reorganization of the nation (Pimentel, 2007, p. 74). Official preoccupation with the excessive use of denunciation by individual citizens was not particular to the Salazar dictatorship. In Soviet Russia and in the German Democratic Republic, officials also became weary of a phenomenon considered – in theory at least – not only contrary to the ideal of a harmonious socialist society but unreliable for police work (Gellately, 1996, pp. 957-958).

[2]The Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado [International and State Defense Police] existed between 1945 and 1969, when it was replaced, for cosmetic reasons, by the Direcção-Geral de Segurança [Directorate-General of Security], during the “Marcellist Spring”. In practice the DGS maintained most of its predecessor's extensive arbitrary powers and actually used them with increasing intensity in the context of growing contestation against the regime (Pimentel, 2011, p. 147).

[3]To a large extent, this interpretation is an elaboration on the pioneering analyses developed by Hermínio Martins, on the “optimal coefficient of terror” achieved under the Salazar dictatorship (Martins, 1998, pp. 44-45), and by Tom Gallagher, on the regime's system of “controlled repression” (Gallagher, 1979).[4] For a more subtly-defined analysis of the use of violence by the police under the Salazar regime, see also Cerezales (2011; 2015).

[5]Which can be translated literally as “For the Good of the Nation'.

[6]In the PIDE archives the names of the authors of the denunciation letters have been (mostly) expurgated by ANTT archivists, in application of Portuguese archival law (Decree Law n.º 16 of 23 January 1993, article n.º 17) which determines that any personal data likely to affect an individual's personal “image” or “security” is to be systematically removed from the documentation. This policy, which has also been applied to the regime's paid informers, is all the more questionable morally since the names of the individuals being singled out for denunciation, often on a purely defamatory basis, have not been expurgated. In the present article all available names will be given.

[7]The regime's obstinate refusal to adapt to the “wind of change” eventually led to war with the African liberation movements in Angola (March 1961), Guinea (January 1963) and Mozambique (September 1964). The conflict ended only in the aftermath of the revolution of 25 April 1974, which toppled the Salazar regime in metropolitan Portugal.

[8]General Humberto Delgado's direct style of campaigning in the June 1958 presidential election had succeeded in gathering widespread popular support for the opposition, and was defeated only by the regime's increased use of political repression and electoral fraud.

[9]The official note was sent for publication in the daily press. See Diário da Manhã, 17 February 1970, p. 1.

[10]Which can be translated loosely as a “poor il Literate fellow'.

[11]A further sample of 81 “spontaneous application letters” sent to the minister of the Interior by members of the public wanting to join the PIDE in 1964 – gathered in the context of our on-going research on the repressive apparatus of the Estado Novo – also suggests that the trend was not insignificant in quantitative terms, and that it concerned primarily, but not exclusively, individuals from the unskilled, lower socio-economic classes. One indicator was the fact that the authors of the letters often enquired about joining the PIDE's cleaning or car-washing staff, ANTT, Ministério do Interior, Gabinete do Ministro (inc. 2003), Registo de Correspondência Recebida, Ano de 1964, NT 34-35-36.