Introduction

Over the last decade, the academic study of populism has been enriched by a stream of research aiming at analysing the demand side of this phenomenon. Some of this research focused on populist attitudes, exploring the extent by which populist ideas are embraced by the citizenry and shedding light on their antecedents and effects (for a systematic literature review, see Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga and Borah, 2022).

One of the most interesting contributions to this line of research was provided by scholars focusing on the impact of populist attitudes on voting behaviour. In general terms, populist attitudes were shown to significantly impact the vote (e. g. Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove, 2014; Spierings and Zaslove, 2017; van Hauwaert and van Kessel, 2018; Stanley, 2019; Geurkink et al., 2020; Marcos-Marne, Plaza Colodro and Freyburg, 2020; Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020; Giebler et al., 2021; Jeroense et al., 2022). However, in a few studies, this effect was not observed at all, in others it was smaller than expected, and in others still it nevertheless needed qualification (e. g. Stanley, 2011; Andreadis et al., 2018; van Hauwaert and van Kessel, 2018; Loew and Faas, 2019; Quinlan and Tinney, 2019; Kenny and Bizumic, 2020; Neuner and Wratil, 2020; Jungkunz, Fahey and Hino, 2021; Kefford, Moffit and Werner et al., 2022; Marcos-Marne, 2021; Castanho Silva, Fuks and Tamaki, 2022; Castanho Silva, Neuner and Wratil, 2022). In short, while populist attitudes are generally seen as relevant drivers of voting behaviour, their impact seems to be far from being impermeable to moderators of different nature, which are currently undergoing a process of identification.

In this article, the aim is to contribute to this literature by claiming that the role of populist attitudes may be different in first- and second-order elections since these contests elicit different motivations (Reif and Schmitt, 1980). Given that the extant research has focused almost exclusively on first-order elections (for a notable exception, see Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020), and comparative studies of different elections are uncommon in this line of research (Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga and Borah, 2022), this possibility has not been explored. Therefore, by filling in this gap in the literature, this article seeks to expand our understanding of the moderators of the electoral impact of holding populist attitudes.

This article also aims to enhance our knowledge of the impact of populist attitudes on the vote in Portugal. Until 2019, this country was portrayed as an exception to the pattern observed in Europe, since no explicitly populist party, either left-wing or right-wing, had flourished (Salgado and Zúquete, 2016; Quintas da Silva, 2018). The shockwaves generated by the Great Recession only led to a modest increase in the populist rhetoric of left-wing parties such as BE (Left Bloc) and PCP (Portuguese Communist Party) (Lisi and Borghetto, 2018), consensually seen as not being full-fledged populist (Rooduijn et al., 2019). At the same time, in Italy, Spain and Greece, populist political parties thrived (e.g. De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira, 2020). Interestingly, the prevalence of populist attitudes in Portugal was neither low (in a 2018 survey, about 40 per cent of respondents displayed high levels of agreement with populism; Santana-Pereira and Lima, 2023) nor dissimilar from what could be observed in other Southern European countries (De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira, 2020).

This panorama changed in the Fall of 2019, with the election of Chega’s leader as member of parliament just about six months after the party was legalized by the Constitutional Court. There are few doubts that Chega (meaning Enough in Portuguese) is a populist radical right party - its issue positions and salience (Mendes, 2021) and its electorate (Heyne and Manucci, 2021) fairly resemble those of other European populist radical right parties; also, its voters tend to be more populist than those of any other Portuguese party in parliament (Belchior et al., 2022). Chega’s advent in 2019 and the electoral success it has had since then - it became the third parliamentary party in January 2022, quadrupled its number of seats in March 2024, and its leader was the third most voted presidential candidate in 2021 (Afonso, 2021; Ferrinho Lopes, 2023, forthcoming) - marked the end of the Portuguese exceptionalism.

However, five years after the advent of Chega, the extant research on populist attitudes in Portugal mainly depicts the pre-2019 context (De Giorgi and Santana-Pereira, 2020; Santana-Pereira, 2020; Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020; Santana-Pereira and Lima, 2023). Notable exceptions are the study by González-González et al. (2022) on populist attitudes and the news find me perception, or the research on populist attitudes and belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories (Ferreira, 2021), both using data collected in 2020. Also, only one of those studies focused on voting behaviour (Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020). Therefore, the third contribution of this paper is to use more recent data to understand if and how populist attitudes matter to voting decisions in a country now marked by the flamboyant presence of a populist radical right party such as Chega and its charismatic leader André Ventura.

Lastly, by comparing voting behaviour in Portuguese legislative and presidential elections, this article also fills in a gap in the knowledge about factors explaining vote choice in the latter, an understudied topic due to scarcity of individual-level data (for two notable exceptions, see Magalhães, 2007 and Freire, 2009).

This article is structured as follows. First, I review the literature on populist attitudes and voting behaviour, discuss the possibility of the impact of the former on the latter being different according to the type of election at stake and present the hypotheses. A subsequent section discusses the nature of the two elections under comparison. Next, the data and variable operationalization strategy is presented. What follows is a presentation and discussion of the main patterns identified via statistical analysis of survey data. The article concludes with a reflection on the main findings and suggestions for future research.

Populist attitudes and voting behaviour

Populism can be understood as a basic set of ideas that provide an interpretive framework of the political sphere. This constitutes an ideational approach to the phenomenon, under which we find Mudde’s (2004) definition of populism as a thin-centred ideology that considers society to be separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic fields (the pure people versus the corrupt elite) and claims that politics should be the expression of the general will of the people. This approach has inspired several studies on populism, either focusing on the supply (e. g. Manucci and Weber, 2017; Lisi and Borghetto, 2018) or the demand side (e. g. Kaltwasser and van Hauwaert, 2020) of this phenomenon.

In this article, the aim is to contribute to the latter field. In more concrete terms, this research focuses on the degree by which citizens express agreement with the constituting elements of the populist worldview, or, to put it differently, the degree by which they hold populist attitudes. This specific field of research flourished after the publication of Akkerman and colleagues’ 2014 article in which a new scale of populist attitudes was presented and tested in the Dutch context. Since then, an array of other scales has been produced (see Castanho Silva et al., 2020) and used in more than 130 English-language publications reporting research on the antecedents and consequences of holding political attitudes (Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga and Borah, 2022).

In still more concrete terms, the present article focuses on the impact of populist attitudes on voting behaviour. Under this umbrella, two specific dimensions have been studied: turnout and vote choice.

Regarding turnout, in a study of nine European countries, Anduiza, Guinjoan and Rico (2019) showed that in six of them there was no relationship between populist attitudes and turnout, but merely between those attitudes and expressive non-institutionalized modes of participation. Santana-Pereira and Cancela (2020) showed that populist attitudes were also not connected with the probability of turning out to vote in the 2019 EP elections in Portugal. Instead, in Germany, Poland and Switzerland, populist attitudes actually depressed electoral participation (Anduiza, Guinjoan and Rico, 2019).

Unsurprisingly, the bulk of research on this topic has focused on vote choice, measuring the impact of holding populist attitudes on the electoral support for a) populist parties and candidates, b) new parties (irrespectively of their degree of populism), and c) other parties (often in contexts without a supply of populist parties in the electoral market).

In several Western and Southern European countries, populist attitudes were found to increase the odds of voting for populist radical right and radical left parties (Spierings and Zaslove, 2017; van Hauwaert and Van Kessel, 2018). In the Netherlands, Geurkink et al. (2020) and Jeroense et al. (2022) noted that citizens scoring high on populist attitudes did have higher odds of voting for the populist radical right PVV (Party for Freedom) but also for the populist left-wing SP (Socialist Party), a finding that resonates with that of the seminal article by Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove (2014).1 Populist attitudes were also found to be associated with a higher propensity to vote for the AfD (Alternative for Germany), as well as for PiS (Law and Justice) in Poland (Stanley, 2019; Giebler et al., 2021). Closer to home, Anduiza, Guinjoan and Rico (2018) and Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro and Freyburg (2020) reported a positive impact of populist attitudes on the odds of voting for the Spanish populist radical left Podemos (We Can). In turn, in a context with no supply of populist parties, populist attitudes increased the odds of voting for those that scored comparatively high in terms of anti-elitism (Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020).

In what regards voting for new political parties, Santana-Pereira and Cancela (2020) found no impact of populist attitudes on the support for new players in forthcoming second-order (European) elections in Portugal, while Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro and Freyburg (2020) do report that populist attitudes increased the odds of voting for new parties as different as Podemos and centre-right nonpopulist Ciudadanos (Citizens) in Spain.

Lastly, populist attitudes lower the odds of voting for elitist, establishment parties in Canada (Medeiros, 2021), as well as for the incumbent party in contexts in which no blatantly populist party was around (such as Portugal in 2018; Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020), in which a populist party was running for the first time (such as 2015 Spain; Anduiza, Guinjoan and Rico, 2018) and in which left- or right-wing populism were far from being a novelty, such as Poland or the Netherlands (Stanley, 2019; Hameleers and de Vreese, 2020).

Against this panorama, there is an array of studies in which the role of populist attitudes was far from clear. First, a series of contributions suggest that thick (right-wing or left-wing ideals and preferences) matters more than thin (a populist worldview) ideology when it comes to explaining populist party success. Stanley (2011) found that the impact of populist attitudes on the vote in the 2010 Slovak legislative election was negligible and much smaller than that of nationalist and economic attitudes. A few years later, Quinlan and Tinney (2019) noted that populist attitudes were far from being the most important predictors of populist voting in Ireland and the USA, stressing instead the importance of ideology, partisanship and economic perceptions. In a similar vein, Castanho Silva, Fuks and Tamaki (2022) found that populist attitudes had a negligible impact on the vote for Jair Bolsonaro in the Brazilian 2018 presidential elections, even within centre-right voters, being illiberal attitudes and right-wing ideology the key drivers of his electoral support. Lastly, a conjoint experiment carried out in Germany and replicated in the USA showed that citizens with strong populist attitudes were not more attracted to candidates with populist positions (such as people-centrism or anti-elitism) than those who rejected the populist worldview, and that substantive issues were at the core of candidate choice (Neuner and Wratil, 2020; Castanho Silva, Neuner and Wratil, 2022).

Second, there is research showing that not all components of the populist ideology matter, although the evidence is mixed. For instance, in Australia, people-centrist attitudes (but not anti-elite attitudes or a Manichean outlook of the world) were associated with the vote for One Nation (Kenny and Bizumic, 2020), while a subsequent study of the same case ( Kefford, Moffit and Werner, 2022) reported a positive impact of anti-elitism but not people-centrism or Manichean outlook. Similarly, Quinlan and Tinney (2019) showed that anti-politician sentiments were key to explaining vote for populists in Ireland but not for Donald Trump in the USA. In the latter case, nativist and anti-immigration attitudes, typical of right-wing populist parties but outside the scope of the minimal definition of populism, were the relevant populism-related predictors.

Third, the importance of considering the interplay between thick and thin ideological stances of citizens have been also addressed in the specialized literature. For instance, focusing on a pool of nine countries, van Hauwaert and van Kessel (2018) showed that populist attitudes function as a “motivational substitute” for issue proximity, leading some highly populist voters to support populist parties whose substantive positions are different from theirs (p. 83). Loew and Faas’s (2019) case study of Germany pointed in the same direction. In turn, Marcos-Marne’s (2021) findings on the interaction between populist attitudes and ideology as drivers of voting for Podemos in 2015 do not resonate with this pattern, as populist attitudes significantly increased the likelihood of voting for left-wing populist parties first and foremost among individuals with left-wing substantive preferences.

Fourth and last, meso- and macro-level dimensions can be relevant. For instance, party status seems to matter: Jungkunz, Fahey and Hino (2021) showed that populist attitudes explain the vote for populist opposition parties but the same does not happen when they are incumbents. The authors explain this trend by the fact that the mainstream measures of populist attitudes leave aside negative attitudes towards elites other than politicians (the media, intellectuals/scientists, bureaucrats or businesspeople), which are commonly the target of populists when in power. Also, Andreadis et al. (2018) observed strong effects of populist attitudes on the vote in Spain and Greece but not in Chile and Bolivia, underlining the importance of socio-economic conditions and political supply in activating those attitudes and translating them into populist support (on this matter, see also Hawkins, Kaltwasser and Andreadis, 2020).

Efforts to understand variations in the impact of populist attitudes on the vote and identify moderating factors have not yet considered the possibility that those attitudes impact the vote in first- and second-order elections to a different degree. Following the first direct EP elections in 1979, Reif and Schmitt (1980) proposed a distinction between first- and second-order elections. They argued that legislative (in parliamentary systems) and presidential elections (in presidential regimes) are first order, since their result determines who will govern and how. In turn, second-order elections (EP elections, and, to some extent, local elections and presidential elections in weak semi-presidential regimes; see Fortes and Magalhães, 2005 and Santana-Pereira, Nina and Delgado, 2019 for a discussion on the latter two), have no direct influence on who controls national executive power, and consequently are perceived as less important by voters and parties. This distinction has two main impacts in terms of electoral behaviour: lower turnout and better results for smaller parties in second-order elections (Reif and Schmitt, 1980). Over and above protest voting (van der Ejik and Franklin, 1996), this latter pattern is due to the absence of strategic voting, since second-order elections can be seen as a safe environment in which voters can express their real party preferences.

But what do populist attitudes and their impact on populist voting have to do with the second-order election theory? I argue that one can understand the impact of populist attitudes in the vote for populist parties or candidates as a sign of sincere voting, resulting in a vote motivated by the support for the populist worldview. Voting with the heart (van der Eijk and Franklin, 1996) is not, however, the only option available to citizens. In fact, in first-order elections, there are often incentives to vote with the head (van der Eijk and Franklin, 1996) - that is, to give our vote to a party or candidate which is not the one we like the most, either to avoid wasting a vote when the electoral system creates barriers to its translation into representation, or to increase the odds of achieving a specific governmental solution.

My argument is that, since strategic voting is arguably more common in first than in second-order elections, or, to put it the other way around, sincere voting is more common in the latter (Reif and Schmitt, 1980; Carrubba and Timpone, 2005; Schmitt et al., 2020), we might therefore expect stronger effects of populist attitudes on populist voting in second-order electoral races. In short, my expectation is that the higher the populist attitudes, the higher the odds of supporting the radical right-wing populist party/candidate in both the second-order (Hypothesis 1) and first-order elections (Hypothesis 2), but the impact of populist attitudes on the vote will be stronger in the case of the former (Hypothesis 3).

The case under study

The hypotheses presented above were tested in the Portuguese context, with data collected in 2021 regarding vote choice in the January presidential elections and vote intentions in hypothetical legislative elections measured in the Fall. The recency of radical right populism in the country and the modest number of studies on the electoral aspect of this phenomenon, addressed in the introduction, testify to the relevance of this case.

There are few doubts that legislative elections in Portugal are first-order elections, as it is via those elections and their impact on parliamentary composition that the government is appointed. When it comes to presidential elections, however, things get more complicated. Fortes and Magalhães (2005) argue that the applicability of the second-order model to presidential elections in semi-presidential regimes depends mainly on the powers the president has: the more power they have, the more important the election will be and the higher the odds of such election to be seen as first-order. In the case of Portugal, there is a relative consensus on those powers being comparatively weak (Elgie, 2005; Fortes and Magalhães, 2005; Lijphart, 2012; see, however, Amorim Neto and Lobo, 2009 for a slightly different perspective).

Based on this, we can understand the 2021 presidential elections in Portugal as second-order elections and therefore more prone to sincere voting. The fact that these elections were mostly about re-electing president Rebelo de Sousa, formally supported by the main opposition party but informally by the incumbent Socialists (see, for instance, Serra-Silva and Santos, 2023), led them to be remarkably uncompetitive, which is an additional factor reducing the odds of strategic considerations and increasing the likelihood of sincere voting. To the contrary, hypothetical legislative elections in late 2021 could have elicited even more strategic considerations than usual: the panorama was marked by the existence of a centre-left minority cabinet struggling to pass relevant legislation and a main opposition centre-right party having disappointing results in opinion polls (Ferrinho Lopes, 2023).

At the same time, these two electoral scenarios are remarkably comparable. To start, both happened/would happen in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (as the early legislative elections of January 2022 ended up happening; see Santana-Pereira and De Giorgi, 2022 for details). Also, while in legislative elections there are necessarily more candidates than in presidential elections, the party-centric nature of the legislative contest, boosted by the electoral system (proportional representation with closed and blocked lists), leads to a considerable focus on party leaders (often dubbed erroneously by the media as prime-minister candidates), and thus to the prominence of a smaller set of actors. In late 2021, the number of viable parties, according to the polls (e. g. Santana-Pereira and De Giorgi, 2022; Ferrinho Lopes, 2023) was nine, which is similar to the number of presidential candidates in January (seven). Moreover, in spite of the presidential elections not being formally party-centric, most parties had their own candidate running. Lastly, in terms of populist offer, these elections are also comparable: in both instances, only Chega and André Ventura can be associated with radical right populism; to the left, whereas there are traces of populism in both the PCP and BE (e. g. Lisi and Borghetto, 2018; Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020), these parties, and their presidential candidates João Ferreira and Marisa Matias, cannot be described as populist.

Data and variables

This article relies on panel survey data on a representative sample of the Portuguese population aged 18 or more (Belchior et al., 2021), collected via telephone interviews and online. The fieldwork for the first wave took place between 9 April and 19 May 2021, whereas for the second wave the data collection went from 6 September to 25 October of that same year. A total of 556 respondents participated in both waves. The questionnaires used in the two occasions included a populist attitudes scale, as well as measures of vote choice in recent (presidential) and hypothetical (legislative) elections in Portugal, making this data particularly suitable to this article’s goals.

Panel research is not very common in populist attitudes studies, corresponding to less than 10 per cent of all the English-language articles on this matter (Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga and Borah, 2022). Populist attitudes studies using panel data resort to this strategy first and foremost to increase the strength of causality claims or shed light on the direction of causality (e. g. Gründl and Aichholzer, 2020; Eberl, Huber and Greussing, 2021; Plescia and Eberl, 2021; Bos, Wichgers and van Spanje, 2023). Others merely use data from different panel waves due to a lack of data for all the variables under study in one single wave (Geurkink et al., 2020; Zaslove et al., 2021; Jeroense et al., 2022; Werner and Jacobs, 2022). This study follows both logics. On the one hand, I want to compare the exact same respondents faced with two different elections, that being why I rely exclusively on data from those who participated in both waves. On the other, in the case of the legislative election model, the dependent and the independent variables were measured in the second wave, but important controls had to be operationalized with first wave data.

Populist attitudes were measured via a battery of items that constitute an adaptation to the Portuguese language of the Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove (2014) scale. This scale is composed of six items covering people-centrism, anti-elitism and popular sovereignty: the main dimensions of populism encompassed in the definition adopted here.2 This scale is one of the best currently available, as it displays high internal consistency and external validity, while being resilient to different operationalization strategies (Castanho Silva et al., 2020; Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen, 2021). Moreover, it has been used in about half of the empirical articles published over the last decade ( Marcos-Marne, Gil de Zúñiga and Borah, 2022). In this sample, a factor analysis confirmed that the six items measure a single underlying dimension, although reliability in the first wave is modest (Cronbach’s Alpha = .67) and slightly lower than that of the second wave (Cronbach’s Alpha = .74). Two indexes were built: populist attitudes on the first wave and populist attitudes on the second wave (both varying from 1 = low level to 5 = high level). The first is used in the model regarding the presidential elections and the latter in the legislative elections model.

As dependent variables, two dummies are used: vote for Chega’s leader André Ventura in the 2021 presidential election vs. other candidates or abstention, and voting for Chega vs. other parties or abstaining in hypothetical legislative elections. The first dependent variable is a vote recall measure operationalized with data collected during the first wave, while the latter is based on voting intentions collected during the second wave. I decided to keep abstentionists in the analysis due to the small size of the available sample. The fact that I placed non-voters next to those who voted for parties or candidates other than Chega/Ventura is not believed to insert any sort of bias in the analysis, as the extant evidence points to no relationship between populist attitudes and turnout in Portugal (Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020).

The regression models include, as controls, some of the usual suspects impacting voting decisions in general and vote for Chega in specific (e. g. Heyne and Manucci, 2021): age (continuous), gender (1 = female), education (7-point scale, with higher values meaning higher degrees of formal education attained), church attendance (1 = never, 6 = once a week or more often) and monthly household income (1 = less than 500 euros, 7 = more than 5000 euros). Moreover, to cover the thick component of radical right populist voting, which some studies claim is more relevant than the thin component (Stanley, 2011; Quinlan and Tinney, 2019; Castanho Silva, Fuks and Tamaki, 2022), ideology (self-placement in the left-right spectrum, 0 = left, 10 = right) was included in the models. Also, to isolate the possibility of vote for Ventura or Chega being a vote with the boot - that is, protest voting, leading these elections to be seen as a referendum on incumbent performance (van der Eijk and Franklin, 1996; Carrubba and Timpone, 2005) - I also included an indirect measurement of satisfaction with who is occupying the seat at stake (trust in the President or the government, both measured via a 4-point scale) and an assessment of the country’s economic situation (1 = very bad, 5 = very good). Controls were kept to a minimum due to the comparatively small size of this sample, and the rule of thumb of having at least 30 cases per predictor is respected. All control variables were measured in the first wave, except for the perceptions of the economic situation and trust in political institutions, which were measured both in the first and second waves.

Results

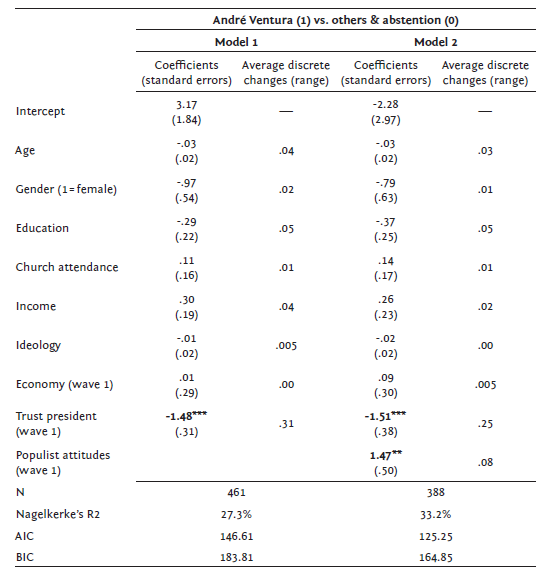

Let us start with an analysis of the factors impacting the vote for André Ventura in the 2021 presidential elections. The model containing control variables (Table 1, Model 1) explains about one-fourth of the variation in the dependent variable, despite only trust in the president being a significant predictor. In fact, those who distrust the president were 32% likely to have voted for Ventura, whereas those expressing high levels of trust were only 1% likely to having done so, when the other variables are kept at their means. Age and gender are close to statistical significance, with a slight trend for men and younger respondents to be more likely to recall having voted for the populist radical right candidate in the 2021 presidential elections. Adding the populist attitudes index into the model (Table 1, Model 2) only slightly reduces the still comparatively strong effect of trust in the president, while increasing the model’s pseudo-R2 and leading to gains in terms of goodness of fit. This variable proves to be significant: while those who score low on this index display a probability of having voted for Ventura which is virtually zero (.03%), those who express strongly populist attitudes were 8% likely to recall having supported him at the polls. Hypothesis 1 is therefore confirmed.

Table 1 Factors explaining vote for André Ventura in the 2021 presidential election

Notes: Average discrete changes (range) represent the difference in the probability of having voted for André Ventura vs. other candidates or abstaining when we move from the lowest to the highest value of the independent variable, with all other variables kept constant at their means. They can therefore be read as a measure of effect size, with higher values representing a stronger impact of the independent variable at stake (on a 0-1 scale). *** = p < .001; ** = p < .01; * = p < .05

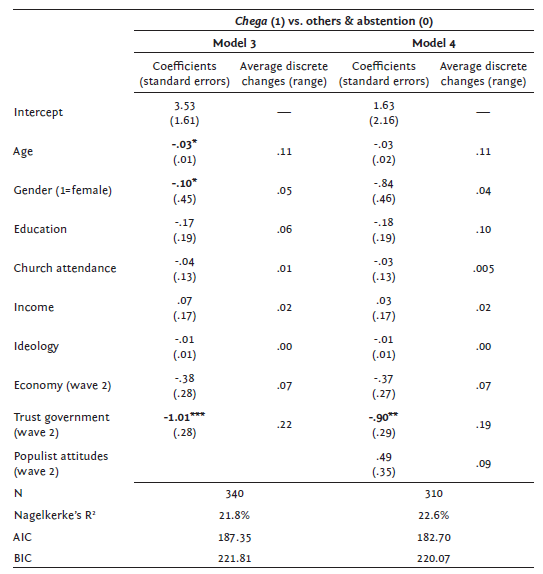

Table 2 Factors explaining vote for Chega in hypothetical legislative elections

Notes: Average discrete changes (range) represent the difference in the probability of voting for Chega vs. other political forces or abstaining when we move from the lowest to the highest value of the independent variable, with all other variables kept constant at their means. They can therefore be read as a measure of effect size, with higher values representing a stronger impact of the independent variable at stake (on a 0-1 scale). *** = p < .001; ** = p < .01; * = p < .05

Next, the impact of populist attitudes on vote intentions in hypothetical first-order elections is analysed. As before, I start with an analysis of the control variables on the likelihood of voting for Chega (Table 2, Model 3). Age, gender and trust in government are relevant predictors of the vote for this party. Regarding the first, while the youngest respondents display a 12% probability of voting for Chega, this figure shrinks to 1% in the case of the eldest, when the other variables are kept constant at their means. Under the same conditions, men were 8% and women 3% likely to vote for this party. Trust is the strongest predictor, once again. By keeping the other variables constant at their means, we see that those who report low levels of trust in government were 23% likely to express an intention to vote for Chega, whereas their counterparts who fully trust the government were only 1% likely to do so. The inclusion of populist attitudes in the model causes both gender and age to lose their statistical significance, whereas it does not add anything in terms of pseudo-R2 or goodness of fit. In fact, populist attitudes are not significant predictors of voting for Chega in these hypothetical elections (Table 2, Model 4). To test the robustness of this negative result, an alternative model including an interaction between ideology and populist attitudes (following the reasoning in van Hauwaert and van Kessel, 2018, Loew and Faas, 2019 and Marcos-Marne, 2021) was computed. The results were still negative: populist attitudes did not explain the intention to vote for Chega vs. other parties or abstention irrespectively of the respondent’s ideology.

There is no alternative, therefore, than to reject Hypothesis 2. In turn, the lack of effect of populist attitudes on the vote for Chega in the hypothetical legislative elections but its significant impact on the vote for André Ventura in the presidential election means that Hypothesis 3 is confirmed to a higher extent than expected.

Conclusions

In this article, the goal was to shed light on the role of populist attitudes as predictors of populist radical right voting in different types of elections. In more concrete terms, it explored the extent to which populist attitudes explain the vote for populist parties or candidates in first-order (legislative) and second-order (presidential) elections to a different degree in semi-presidential Portugal.

The results show that populist attitudes were strong predictors of the vote for the populist candidate André Ventura, increasing the odds of having cast a ballot supporting him. In this election, the main predictor was, however, trust in the president, which depressed support for Ventura. In spite of the perception of the economic situation of the country not being relevant, this result sheds light on protest motivations having been at the core of the decision to vote for the populist radical right candidate for a significant proportion of the electorate, but sincere populist voting was also nonnegligible. The same did not happen in the case of legislative elections. In fact, trust in the government was the most important predictor of the vote for Chega. Again, the logic is one of protest, or referendary (van der Eijk and Franklin, 1996; Carrubba and Timpone, 2005): the less respondents trusted the government, the higher the odds of their intending to vote for the populist party. However, populist attitudes did not achieve statistical significance, neither alone nor interacted with left-right self-placement. This leads to the conclusion that: a) future studies focusing on the role of populist attitudes on the vote for populist political forces must control for short-term protest motivations, and b) it may very well be the case that the impact of populist attitudes is much larger in second-order elections, which are still understudied in this field of research.

Ideology played no part whatsoever in explaining the populist vote in these elections, a result that can be explained by the fact that Ventura/Chega were competing with both left-wing and right-wing candidates/parties. Such a context of competition therefore leads to no evidence supporting the finding that thick ideology may explain voting for populist candidates and parties to a greater extent than thin populist attitudes, something that has been reported in a few articles (Stanley, 2011; Quinlan and Tinney, 2019; Castanho Silva, Fuks and Tamaki, 2022).

There are, however, two alternative readings of the results presented in this article. First, it may very well be that populist attitudes are better at explaining vote recall than vote intentions. Also, it may very well be that, for some unforeseen and yet-to-be-isolated reason, populist attitudes might be stronger predictors of the vote in highly personalised elections, such as the presidential elections in Portugal, and less so in strongly party-centric elections such as the legislative contests in the country. In order words, the key factor may be personalisation and not second-orderness. Subsequent research should therefore, using the appropriate data we currently lack, shed light on these possibilities. Since two party-centric elections took place in the first half of 2024 - one first-order (the legislative election of March 10) and one second-order (the EP election of June 9) - the political context in Portugal offers an opportunity to revisit these findings, provided that the appropriate data on populist attitudes and vote recall is available.