Theoretical framework and methodology

After two decades of delay, the fourth wave of the radical right with electoral relevance (Mudde, 2019) has also arrived in the Iberian Peninsula, through the parties Vox in Spain and Chega in Portugal (Mendes and Dennison, 2021).1 Following Cas Mudde’s typology, the two Iberian parties are usually considered Populist Radical Right Parties (Heyne and Manucci, 2021a), i. e. guided by an ideology composed of three key elements: nativism, authoritarianism, and populism (Rama et al., 2021; Mendes, 2022). Until the emergence of Chega, few studies on radical right-wing populism in Portugal focused on the ideology and mobilization of Ergue-te (Rise up): a fringe party, founded in 1999 under the name National Renewal Party (Partido Nacional Renovador - PNR). Ergue-te belongs to the old extreme right - that is linked to the authoritarian past (Ignazi, 2003) - and is electorally irrelevant (Zúquete, 2007; Salgado, 2019). Chega’s electoral success has promoted and extended the study of radical right populism to its leader’s discourse (Dias, 2022), its program (Braz, 2023), and the political demand of voters (Heyne and Manucci, 2021b; Afonso, 2023). According to some authors, Chega reveals a marked degree of populism compared to other parliamentary parties - except for the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) - in the dimensions of anti-elitism, the idea of the virtuous people, and the defense of popular sovereignty (Palhau, Silva and Costa, 2021). Its populism is punitive nativist and identitarian conservative. It is punitive nativist due to the law-and-order warnings against outsiders allegedly dangerous for the safety of insiders (López-Rodríguez, González-Gómez and González-Quinzán, 2021). It is identitarian conservative because it highlights the differences between Portuguese and non-Portuguese (Madeira, Silva and Malheiros, 2021). Although the alleged “Islamist danger” is present in Chega’s warnings against the “terrorist threat”, the still low level of immigration in Portugal means that the law-and-order discourse focuses on the Indigenous people of the Roma ethnic minority and problems of their integration, subsidization, and micro-criminality (Afonso, 2021). According to some authors, this discourse combines the cultural dimension with the biological (Mendes, 2022), in the form of neoliberal cultural xenophobia (Carvalho, 2023). Many of the authors who have investigated Chega are inspired by literature that considers racism to be at the heart of radical right ideology, expressed indirectly and surreptitiously through culturalist discourse (Mulinari and Neergraard, 2015; Mondon and Winter, 2020; Kapoor, 2021). According to this literature, populism would therefore be secondary to nativism (Sengul, 2022). Others, on the contrary, analyze Chega based on the idea that opposition to immigration does not make a party racist or xenophobic per se and that, in any case, the extent and intensity of these attitudes is an empirical question (Fennema, 1996; Rydgren, 2008). Moreover, in the wake of the debate between Cleen and Stavrakakis, on the one hand, and Brubaker, on the other (Cleen and Stavrakakis, 2020; Brubaker, 2020), Chega moves quite flexibly in the ambiguity of the vertical dimension of populism (the people against the elite) and the horizontal dimension of nationalism (the ingroup against the outgroup). The party explores both the autonomy and the interconnection between the two dimensions: Chega’s anti-elitism does not exclude an anti-leftist alliance with sectors of the elite; its nationalism does not segregate the community along ethnic lines but opens it up to cultural assimilation and economic functional integration.

In general, scholars have based their characterization of Chega on the leader, the program, and, to a lesser extent, the electorate, but they have neglected the party’s militant base. In international literature, studies on radical right militants are rare (Whiteley et al., 2021). This is due to the difficulty researchers have in overcoming the classic mistrust of militants and leaderships of radical right movements and parties (Pirro and Gattinara, 2018). So far, only exploratory research on the party’s founders has been carried out (Marchi, 2020). To fill this relevant gap, an online survey of Chega activists was carried out between May 24 and June 16, 2021. The survey was distributed to members by the party itself, via its institutional mailing list. The survey consists of 38 questions, distributed in four sections: sociographic characterization; attitudes towards politics and democracy (with particular attention to issues of national identity, minorities, and migrations); values; and the European Union. The questions were taken from national surveys, namely the Portuguese Electoral Study 2019 (on national identity, migration, minorities), the European Social Survey 2018 Round 9 (on race and culture), the Portuguese Electoral Study 2015, and Eurobarometer 2020 (on the European Union). The validated sample - probabilistic, non-representative - consists of 3,183 participants.

The presentation of the results is preceded by a description of the historical trajectory of Chega and its leader André Ventura, to highlight the programmatic and discursive strategy that won over thousands of members in just two years, something unprecedented for the radical right in Portugal. The survey data is presented in three sections: the sociographic characteristics of the sample, attitudes towards politics with a focus on representative liberal democracy, and attitudes towards national identity highlighting the issues of immigration and ethnic minorities.

André Ventura’s career and CHEGA

Forty-five years after the founding of Portuguese democracy on April 25, 1974, the legislative elections on October 6, 2019 brought the radical right to the national parliament in an unprecedented way, with the election of André Ventura as the sole deputy of Chega (Fernandes and Magalhães, 2020). Chega was founded in 2018 by André Ventura, a cadre of the Social Democratic Party (PSD), in controversy with the centrist line followed by the then party leadership. Chega initially emerged as faction of the PSD, to promote the internal rise of André Ventura, a fan of hard-right European politicians - such as Nicolas Sarkozy, Minister of the Interior in 2005 against the young people of the Parisian balieue - and of protest populism - such as the Italian Five Stars Movement (M5S). Ventura debuted this line for the first time as the head of the list for the center-right coalition PSD-CDS-PPM (Social Democratic Center - CDS and People’s Monarchist Party - PPM) in the 2017 municipal elections in Loures. In that campaign, André Ventura used a radical discourse - unprecedented for the center-right - to address sensitive socio-political divides: the integration problems of the Roma community in Loures (school dropouts, subsidy dependency, micro-criminality). The aim was to polarize public opinion and gain the attention of the media. The strategy succeeded: attacks from political opponents and criticism from coalition partners - the CDS left the coalition in protest - made André Ventura a nationally controversial figure, expanding his already existing notoriety as a television pundit on crime and sports programs.

Despite his media success in the 2017 municipal elections, André Ventura’s path was arduous at first. The Movement Chega created within the PSD to win over the party was a failure. Its transformation into an autonomous party in October 2018 did not represent a consistent split of PSD cadres and militants, but merely the initiative of André Ventura. The difficulties of legalization at the Constitutional Court forced Chega to run in the European elections in May 2019 in coalition with two small parties - the People’s Monarchist Party (PPM) and the Citizenship and Christian Democracy Party (PPV/CDC) - and with the Democracy21 movement. The Basta coalition won just 1.49% of the vote (just under 50,000 voters) and no MEP. The poor result was confirmed in the regional elections in Madeira in September 2019, with just 0.43% (600 votes).

In the European campaign, Chega was rehearsing its conservative political identity in terms of values and liberal in terms of the economy (inspired by Hayek and von Mises, with measures such as the 15% flat tax and the transformation of the state into a financier, but not a provider of services, including health and education). The political supply was law and order, with controversial measures such as reducing the number of deputies in the national parliament, life imprisonment for heinous crimes, and chemical castration for pedophiles. On the specific issue of Europe, Chega adopted the anti-federalist Europeanism typical of the Portuguese mainstream right, aware of the unpopularity of Euroscepticism in Portuguese public opinion.

In the election campaign for the October 2019 legislative elections, Chega confirmed the combination of liberal-conservatism and anti-system rhetoric: denouncing partitocracy and corruption, claiming for constitutional revision to establish a presidential Fourth Republic, strengthening security policies and the fight against subsidy dependency - with a particular focus on the Roma ethnic minority - and the cultural fight against the progressive agenda (political correctness, so-called gender ideology, the LGBT agenda, structural racism). This time, André Ventura managed to get into parliament with only 66,448 votes (1.3%), very concentrated in the Lisbon electoral district, the only one accessible to small parties.

The election and its aftermath allowed the party to grow rapidly from 700 members in 2019 to 40,000 in 2021. Although these official party numbers may have been inflated, the remarkable dynamic of growth was evident. The initial success and low stigmatization by the media, compared, for example, to the classic far-right Ergue-te (Mendes and Dennison, 2021), helped to boost the status of Chega as a credible interlocutor to the center-right. In 2020, the PSD-CDS-PPM coalition in the Azores made Chega’s external support official in order to enable the government that ended twenty years of Socialist power in that Autonomous Region. The written agreement with the right-wing radicals led to strong criticism; it also facilitated the cordon sanitaire for the next electoral campaigns - the 2022 and 2024 legislative elections. The fears of the center-right were related to Chega’s ability to win over voters from the PSD and CDS, who were unhappy with the centrist line of the two parties.

In the three years since entering parliament, the party has continued to be identified with its leader André Ventura and his discourse of messianic, charismatic, and authoritarian populism (Dias, 2020). However, from a programmatic point of view, it has undergone significant changes. It continued to favor Atlanticism and anti-federalist Europeanism in foreign policy, as well as conservatism in values but abandoned radical neoliberalism in the economy (Mendes, 2022). The party insisted on criticizing the excessive tax burden of the state but assumed the principles of complementarity between the public and private sectors in the provision of services and the subsidiarity of the state whenever the free market does not guarantee citizens’ access to essential services.

On the international front, since July 2020, Chega is member of the Identity and Democracy (ID) Eurogroup, led by Marine Le Pen’s French Rassemblement National and Matteo Salvini’s Italian Lega; currently it is forging closer ties with the Vox party in Spain (member of the Europeans Conservatives and Reformists - ECR Eurogroup); it is looking with interest at Hungarian leader Viktor Orbán and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

Chega’s growth was consolidated in the January 2021 presidential elections, when André Ventura’s candidacy won third place, 12% of the vote (almost half a million voters), very close to second place. The presidential campaign confirmed André Ventura’s attractiveness, especially on social media (Serrano, 2021), which contributed greatly to the party’s success through its leader. In May 2021 local elections, Chega won an average of 4.16% of votes nationwide. In the legislative elections on January 30, 2022, won 7% of the vote and grew from one to twelve deputies. The parliamentary space of the center-right thus underwent a profound change: Chega became the third parliamentary force, behind the Socialist Party (PS) and PSD; the historic party of the Portuguese right, CDS, disappeared from parliament for the first time since 1974; the Liberal Initiative (IL) elected 8 deputies, with 5% of the electorate, significantly increasing the result of 2019 (1.3% and one single deputy). Chega’s exponential growth was amply confirmed by the legislative elections of 10 March 2024: with 18% of the vote, Chega elected 50 MP and achieved a very impressive result when compared to the 80 MP of the winning coalition (78 PSD + 2 CDS, just 3 more than in the 2022 legislature) and the 8 MP of IL.

Chega’s performance in the five elections between 2019 and 2024 revealed a strong party in areas of the center-south and interior of Portugal, traditionally controlled by the communist left, without, however, inferring a transfer of votes from the radical left to the radical right (Magalhães, 2019). On the contrary, the results show that both the abstentionist electorate (dissatisfied with the traditional party system) and the center-right electorate (dissatisfied with PSD and CDS) were captured (Fernandes and Prata, 2021). Chega was also successful in areas with a strong presence of the Roma ethnic minority, associated by André Ventura with subsidization and micro-criminality. Some analysts describe Chega’s electoral map as the geography of discontent and resentment, focused on identity rather than economics (Madeira, Silva and Malheiros, 2021). As far as the characterization of the electorate is concerned, Chega voters are mostly men (two out of every three voters), concentrated in the 18-54 age cohort and with secondary education rather than basic or academic education (Cancela and Magalhães, 2022). At the dawn of the party, in 2020, the still few voters were mainly men, aged between 25 and 44 and with a higher education than the average Portuguese (Magalhães, 2020). Concentrated in rural areas, this electorate is characterized by a strong religiosity; by dissatisfaction with traditional politics, which it follows a lot through social media; it expresses a strong cultural criticism of globalization and immigration, although it does not belong to the social strata most affected by economic stagnation in Portugal: the losers of globalization (Heyne and Manucci, 2021b).

Political culture and attitudes of CHEGA activists

Characterization of the sample

Given these characteristics of the party and its leader, who are the many thousands of citizens who have joined Chega since 2019 and what do they think? The validated sample of 3,183 respondents to the online survey provides a relevant picture.

The sample is made up of 84% males and only 16% females. From a geographical point of view, it is mainly concentrated in the Lisbon metropolitan area (43.1%), in the north of the country (29.2%), in the center (14.6%), and, to a lesser extent, in the rest of the country (6.5% Algarve; 3.7% Alentejo; 2.1% Madeira; 0.9% Azores). By age group, 32.5% are aged 45-54; 21.8% are aged 35-44; 20.4% are aged 55-64; 12.3% are over 65; 9.5% are aged 25-34 and 3.5% are aged 18-24. There is a high level of education: 23.2% have a degree and 9.5% have a master’s or doctorate; 34.1% have finished secondary school and 13.2% have completed secondary school (university or polytechnic baccalaureate, courses at the former Industrial and Commercial Institutes, Primary Teaching, etc.). Only 0.1% had no schooling and 15.5% had basic education (0.8% first cycle, 4.5% second cycle, and 14.3% third cycle). Regarding marital status, 64% of respondents are married or in a de facto union, 16% are divorced, and 19% are single. Regarding professional status, 60.2% are employed full-time, 12.4% are retired, 6.4% are unemployed, 2.9% are students, and 2.4% are employed part-time. The 11.8% reporting other unspecified and residual situations are the percentages of unpaid family workers (1.3%), domestic workers doing household chores (1%), and employed less than part-time (0.3%).

The majority of respondents (52.5%) defined themselves as belonging to the middle class, 28.6% to the lower middle class, 13.1% to the upper middle class, 4.6% to the lower class and 1.2% to the upper class. In terms of monthly household income, 43% of the sample declared between 951 € and 2000 € (22% between 951 € and 1400 € and 21% between 1401 € and 2000 €), 18.8% between 2001 € and 3000 €, 10.5% between 3001 € and 5000 €. Only 4.1% say they earn less than 600 € and 5.9% more than 5,000 €, while 3.7% don’t answer.

With regard to religious identity, 67.9% belong to some religion and 32.1% have no affiliation. Of the latter, 39.5% are atheists, 29.5% are agnostics, and 31.1% did not answer. Among the religious, 90.1% are Catholic, 6.9% belong to another Christian religion (2.7% Protestant, 0.4% Orthodox, 3.8% other), 0.4% Jewish, 0.1% Islamic, 0.3% from Eastern religions, and 1.1% from other non-Christian religions. The data shows, however, the effect of secularization: only 1.7% of those surveyed attend religious services daily, 17.2% weekly (3.8% more than once a week and 13.4% only once a week), 16.3% at least once a month, 15% only on holy days, a relevant 34.3% not even on every holy day, and 15.4% never attend.

Attitudes towards politics

Chega members show a high level of interest in politics: 53% of respondents declare “a lot of interest” and 43.2% “some interest”, with only 3.8% having little or no interest.

However, 75.6% never had a party affiliation before joining Chega and only 24.4% belonged to another party. Among the latter, 45.2% came from the PSD (to which can be added 3% from Alliance party, the PSD split of 2018) and 22% from CDS-PP. Former IL members are residual (0.4%) and only 3.1% come from the traditional radical right, Ergue-te/PNR, whose reduced militant base is less able to contribute. From the left-wing, 9.6% of respondents come from the PS and 3.4% from the PCP. Former members of green or other radical left parties are irrelevant (1.4% from the Leftist Block - BE and 0.5% from the People-Animals-Nature - PAN).

As far as electoral behavior is concerned, 75.1% of those polled voted for Chega in the 2019 legislative elections. Among those who didn’t vote Chega, 11% voted PSD (0.8% voted Alliance), only 3.8% CDS-PP, and 1.8% IL (1.8%). The left-wing parties were residual: PS 1.4%, CDU (PCP/PEV) 0.4%, BE 0.3%, Livre 0.1%, PAN 0.5%. The blank vote was also not particularly significant (2.3%).

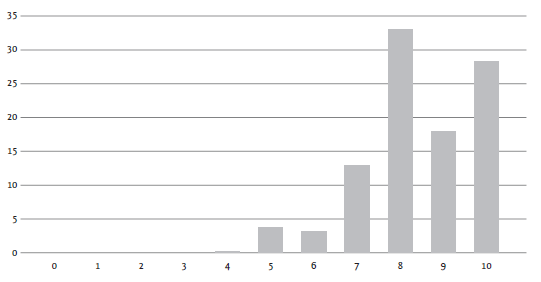

On the 0 to 10 left-right scale (Chart 1), 79.1% of respondents are concentrated in positions 8-9-10, 20.1% in positions 5-6-7, and a mere 0.9% are equally distributed in positions 0 to 4.

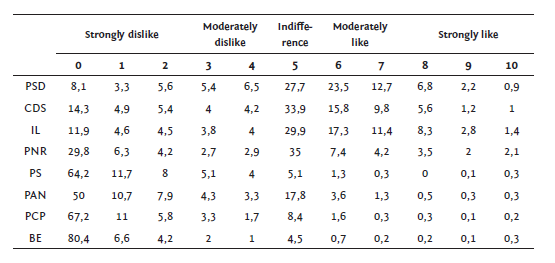

Sympathy for the other parties is consequent (Table 1).

Respondents sympathize mainly with the PSD and CDS. In the case of the PSD, 36.2% declared moderate sympathy, only 9.9% strong sympathy, a relevant 22.7% indifference, and 8.1% extreme dislike. In the case of the CDS, 25.6% declared moderate sympathy, only 7.8% strong sympathy, 33.9% indifference, and 14.3% extreme dislike. The case of the IL is similar to the CDS: 28.7% have moderate sympathy, only 12.5% strong, 29.9% indifference, and 11.9% extreme dislike. Among the left-wing parties, the BE is strongly disliked by 80% of those polled, surpassing the PCP by ten percentage points. The opinion about the traditional radical right party, Ergue-te/PNR, is interesting: 29.8% of those polled for Chega show extreme dislike, 35% indifference, and only 7.6% strong sympathy.

The distrust of other parties indicates a populist feeling of division between the virtuous people and the corrupt traditional political elite. However, this feeling is not highly polarizing. Asked about the meaning of compromise in politics, 54.1% of respondents consider compromise to be a betrayal of their principles. The percentage is not overwhelming: 25% of the sample disagrees with this statement and 20.9% don’t have a definite position. In other words, the members of Chega do not show any unyielding opposition to political compromise; on the contrary, a significant percentage of them consider it to be part of the democratic game.

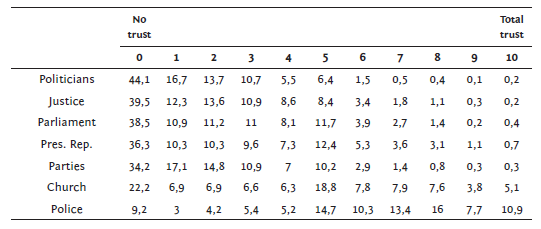

Populist impulses emerge most clearly in the question about the relationship between politicians and the interests of the people. Overall, Chega members show strong feelings of anti-politics: 44.1% and 34.2% of the sample declare no confidence in parties and politicians, respectively (Table 2). For 89.3% of the sample, most politicians are not interested in the people (51.5% completely agree and 37.8% agree), while only 6.1% disagree, and 4.5% do not express a position. In particular, 83.6% of respondents assume that members of Parliament should follow the will of the people and not the elites. Only 5.1% disagreed with this position and 11.2% did not express a position. For 75.6% of the sample, most politicians are only concerned with the interests of the rich and powerful. Only 11% disagree and 13.3% don’t take a stand. For 82.3% of respondents, the differences between the elite and the people are greater than the differences among the people. Only 6.3% disagree with this dichotomous view and 11.4% take no position (neither agree nor disagree).

For 86% of those surveyed, the majority of politicians are not trustworthy. Only 6.2% recognize them as such and 7.7% do not express a position. The explanation lies in the fact that 95.9% of the sample considers certain corrupt practices - for example, accepting bribes - to be widespread among Portuguese politicians. Only 4% reject this idea. As a result, 59.1% of respondents think that the people should be represented by ordinary citizens and not by politicians. Only 17.6% disagree with this idea and 23.2% take no position (neither agree nor disagree).

Distrust affects all the regime’s institutions (Table 2). The police are the most trusted institution: 10.9% of respondents are concentrated in the total trust position and 62.1% are equally distributed in positions of trust between 5 and 9. At the opposite pole, 9.2 occupy position 0 of no trust, but the remaining positions of distrust are held by only 17.8 of those surveyed. For the other institutions, the position of no confidence concentrates significant percentages: 39.5% for the judicial system, 38.5% for the Parliament, 36.3% for the president of the republic. The Church registers a relevant 22.2% of no confidence, against only 5.1% of total confidence, and a peak of 18.8% in the intermediate position.

These attitudes do not, however, lead to anti-democratic tendencies. For 70.3% of the sample, democracy is the best form of government, despite its problems. Only 13.5% disagree and 16.1% neither agree nor disagree. These percentages are similar to those collected by Roger Eatweel and Matthew Goodwin on the supporters of national populism, which led them to state that “they are generally not anti-democrats who want to tear down our political institutions. Since the 1980s, national populists in general (unlike neo-fascists) have eschewed […] anti-democratic appeals. Opposing democracy is no longer a vote winner. Nor do their voters want to overthrow the democratic system” (Eatweel and Goodwin, 2018, pp. 117-120). In line with the trend of the radical right electorate, Chega members are dissatisfied with the way democracy works but support democracy as a form of government. On the 0 to 10 scale of satisfaction with the functioning of democracy in Portugal, 36.4% declared themselves extremely dissatisfied and only 0.5% extremely satisfied. The 39.3% are evenly distributed in the positions of dissatisfaction 1-2-3, and only 15.9% in the positions of moderate dissatisfaction 4-5. On the other hand, the most satisfied positions (6-7-8-9) have only 7.8% of respondents.

The perception of the dysfunctionalities of representative democracy leads to the adoption of forms of direct democracy. Although the majority of respondents consider a system where laws are decided by representatives elected by citizens to be good (50.1%) and very good (9.1%), a consistent percentage have the opposite opinion (30.5% consider it bad and 10.3% very bad). As a result, 74.4% of respondents consider a democratic system where laws on the main national issues are voted on directly by citizens and not by elected politicians to be good or very good. Only ¼ of the sample disagrees: for 20.3% it is a bad system and for 5.3% very bad. In the same vein, for 59.3% of the sample, ordinary people and not politicians should make the most important decisions. 22.8% do not agree with this statement and 18% do not take a position.

The idea of national identity

At the time of the survey, immigration was not a priority concern for Chega members. Portugal’s two main problems were identified by the respondents as corruption and judicial system. Immigration appeared less prominently in a secondary set of problems, behind education, the economy, and the welfare state.

In any case, when asked about this specific topic, the position of Chega members on foreigners and ethnic minorities has nativist characteristics. The classic components of ethnicity - language, territory, ancestry - all have a relevant weight. For 85.1% of those surveyed, the fact of having been born in Portugal is important (very and fairly) for an individual to be considered Portuguese. Only 15% consider this aspect to be of little or no importance. The territorial dimension goes hand in hand with the principle of ius sanguinis: 82.6% of respondents consider it very or fairly important to have Portuguese ancestors in order to be considered Portuguese. In this case, too, only 17.4% undervalue the dimension of ancestry. The linguistic factor is even more consensual: 93.3% of the sample consider it very or fairly important to speak Portuguese to be Portuguese, compared to only 6.8% who consider it not very or not at all important. Similarly, being Portuguese implies following Portuguese customs and traditions: 93.6% of respondents consider this to be very or fairly important, compared to only 6.4% who consider it to be not very or not at all important. The process of secularization also has an impact on this dimension, with belonging to the Christian religion being less valued as a factor of national identity: only 45.8% of those surveyed consider it to be very or fairly important, compared to the majority who consider it to be not very (29.3%) or not at all important (24.9%).

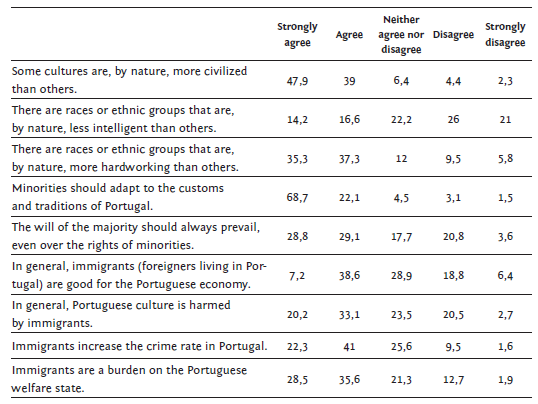

The positions on the ethnic minorities present in Portugal confirm nativism (Table 3). Firstly, the cultural differences between peoples are ranked in an evaluative way. For 86.9% of respondents, there are cultures that are more civilized than others, against only 6.7% who reject this idea, and 6.4% who neither agree nor disagree. The biological-racial dimension is more questionable. On the one hand, when asked about the existence of races or ethnic groups that are inherently less intelligent than others, 47% of respondents disagreed with the statement, compared to 30.8% who agreed. The significant percentage of those who neither agree nor disagree (22.2%) may reveal the pressure of the anti-racist social norm. On the other hand, when asked about the existence of races or ethnic groups that are inherently more hardworking than others, 72.6% of respondents agreed with the statement, compared to only 15.3% who disagreed, and 12% who had no position.

With regard to minorities, for 90.8% of those surveyed, they have to adapt to Portugal’s customs and traditions (4.6% disagree and 4.5% take no position). In this sense, for 57.9% of respondents, the will of the majority must always prevail, even over the rights of minorities, against 24.4% who reject this statement and 17.7% who take no position either for or against.

On the economic front, the negative view of the “other” decreases significantly. For 45.8% of respondents, foreign immigrants living in Portugal are good for the Portuguese economy, compared to 25.2% who disagree. The significant percentage with no position (28.9%) can be explained in two ways: not wanting to admit the positive effect of economic immigration or not wanting to make their opposition to immigration explicit.

The culturalist opposition to immigration is more evident. 53.3% of respondents consider immigrants to be a threat to Portuguese culture, against 22.3% who disagree. In this case, too, the 23.5% without a position may reveal a reticence to openly assume radical anti-immigration rhetoric. Securitarian opposition stand out even more. For 63.3% of the sample, immigrants increase the crime rate in Portugal, against only 11.1% who reject this idea and 25.6% who take no position. Considering the chauvinism of the welfare state, 64.1% of respondents consider immigrants to be a burden on Portugal’s social security system, against 14.6% who reject this idea and 21.3% who don’t take a position.

The nativism of Chega members does not, however, exclude positions of civic nationalism, especially in relation to assimilated foreigners. For 93.4% of those surveyed, the fact that an individual feels Portuguese, regardless of their ethnic origin, is very or fairly important for them to be considered Portuguese. Only 6.7% of the sample undervalued this feeling. At the same time, obtaining Portuguese nationality is very or fairly important to 68.8% of respondents, compared to 31.2% who consider it to be not very or not at all important. This figure is significant when compared with the idea of the more radical fringes of Portuguese nationalism that consider nationality to be inherited by blood ties and not acquired through bureaucratic processes.

Conclusions

The characteristics of the sample reveal the typical political culture of the populist parties of the radical right, alien to the fringe culture of traditional right-wing extremism. Chega’s militant base comes largely from mainstream center-right parties or persons without previous party affiliation who have long been disillusioned with traditional parties.

Attitudes towards politics are aligned with the political culture of protest populism: a strong dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy and a marked distrust of the regime’s institutions. Attitudes towards national identity fit into identitarian populism: a strong sense of belonging to a relatively homogeneous ethnic community rooted in history. Chega members, however, do not seem to be particularly polarised in populism and nativism, either in terms of political or affective polarization. In fact, in several indicators of attitudes towards institutions or members of an out-group, they do not concentrate their answers at the most extreme points of the scale.

As far as their dichotomous view of reality is concerned, Chega members recognize the vertical fracture between the people and the elite but do not seek to replace representative democracy with direct and plebiscitary democracy. On the contrary, they demand the selection of a new elite to serve the general will and the greater participation of the people in specific, relevant moments of the decision-making process.

As far as nativism is concerned, Chega members are guided by the principle of majoritarianism towards minorities, with securitarian and culturalist characteristics.

The survey revealed controversial indicators in important aspects of nativism and populism that suggest the need for future qualitative research to investigate in depth the many facets of the reasons for affiliation to radical right-wing populist parties.