Calling a Spade a Spade: The Concept of Populism in the Portuguese Press

Populism threatens to transform liberal democracies. The Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump, in 2016, prompted a widespread usage of the term, extending its influence from academic circles to media and the political sphere. Populism progressively went from being a “sexy” term (Rooduijn, 2019) to becoming part of our everyday lexicon.

Within academia, there has been a notable surge in scholarly production on populism over recent years (Kaltwasser et al., 2017, pp. 10-13). Yet, the very definition of populism remains a subject of debate within the field. As a result, some elements of this conceptual dispute are expected to feature in media and political discourse. In the public sphere, the use of the concept often lacks rigorous criteria and tends to be influenced by varying national and local contexts.

Portugal, for instance, was previously characterised by its “exceptionalism” to populism, as the country was immune to the emergence and success of populist parties until the arrival of Chega, a radical right-wing populist party (Heyne and Manucci, 2021; Silva and Salgado, 2018). Nevertheless, the term populist was used in prior years to define political leaders such as Santana Lopes (Social-Democratic Party, PSD) or Paulo Portas (CDS - People’s Party, CDS-PP). This haziness leads to both ontological and epistemological caveats and explicitly reveals the tensions within the field of cultural production, in which journalists and scholars are implicated. This article focuses on the Portuguese case and addresses the questions of how Portuguese media defines the concept of populism? To whom or what does the concept of populism refer to? How does the scholarly usage of the concept relate to the one used by media professionals?

Consequently, and despite not aiming to draw a comparative research, the rationale of this work is three-folded: firstly, it focuses on disentangling the meaning of populism in the Portuguese public sphere; then, it aims to locate the insights drawn from the Portuguese case within the extant research on the matter; lastly, it explores the diachronic evolution of potential features of populism in Portugal before the appearance of a commonly considered populist party.

Qualitative and quantitative text analysis are put into place for pieces of news containing any mentions of the root word populis*, therefore capturing all variations for the term. The analysis relies on two quality media outlets, Público and Expresso, across a time period of ten years (from 2012 to 2021), thus covering the period before and after the emergence of Chega.

This article is outlined as follows. The first section is dedicated to reviewing the scholarship on the relation between populism and media, including the debates on the definition of the former and some remarks on the Portuguese case. Then, the subsequent section introduces the procedures followed for data collection and the methodology in use, and the third one presents the empirical results. The final section includes a discussion of the results and some concluding remarks.

Populism and the media

A mutually beneficial relationship?

The linkage between populism and media constitutes a central point of research when studying the electoral growth and success of populist parties. In spite of inconclusive evidence (cf. Bos and Brants, 2014; Bos, van der Brug and Vreese, 2011), a substantial body of literature suggests that the media significantly contributes to the rise of populism. Indeed, the growing prevalence of commercial media logic amplifies the visibility of populist messages and issues (e. g., anti-immigration), while also fostering the electoral expansion of populist actors (Mazzoleni, 2003; cf. Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart, 2007; Hameleers, Bos and Vreese, 2018; Kieslich and Marcinkowski, 2020). This relation might thus be seen as a circular and multifaceted one: “an integrated system for the production of user-friendly political news” (Manucci, 2017, p. 593).

In fact, the association between populism and media cannot be dissociated from the process of mediatisation. Following Strömback’s (2008) review of the concept, mediatisation refers to a process in which media logic elements and techniques become dominant within the political field.1 This way, populism is potentially seen as a result of the mediatisation of contemporary politics, as illustrated by some of its typical attributes: direct appeals to the citizens and the electorate, and a communication style that privileges “spectacularisation, personalisation, sensationalism, tabloidisation, conflict-centred discourse, and simplified rhetoric” (Waisbord, 2019, p. 226). Additionally, the diffusion of a populist message may also be attributed to media outlets (media populism), “when media actively ‘performs’ populism themselves, aligning themselves with or actively celebrating ‘the people’ whilst attacking ‘the elite’” (Moffit, 2019, p. 241; see also Krämer, 2014). In any case, as media become more interested and dependent on commercialising its content and political actors strive for visibility, the latter adjust their presence and speech in the public arena2 to be mentioned by news outlets.

Briefly, in the mediatised context of politics, populism becomes relevant and, thus, newsworthy (Galtung and Ruge, 1965). Additionally, as the positioning of media towards the populist message may assume the roles of gatekeepers, interpreters or originators, it is suggested that the former have been failing in the gatekeeping function by facilitating a stage for increasing populist visibility; in turn, media also provides a negative assessment as interpreters (Wettstein et al., 2018, p. 478).

What’s in a word?

A constraint of this line of research stems from the lack of a common and uncontentious concept of populism (Manucci, 2017, p. 599). Indeed, the general literature on populism is similarly characterised by an often unclear and divided use of the term (Hunger and Paxton, 2021).

Despite multiple conceptual strands, scholars have tended to converge on the ideational approach to populism (Hawkins, 2019; see Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018). For instance, Rooduijn (2014) suggested that a minimal concept of populism would be essentially ideational, reflecting the ideas of people-centrism and anti-elitism, the homogeneity of the people and a narrative of crisis. Notwithstanding, the ideological definition has become prevalent, and populism is thus usually conceived as a thin-centred ideology that divides society into the pure people and the corrupt elite, while arguing that politics should follow the popular will (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017, p. 17). Besides gathering a large consensus within the literature, this definition is also of great use as it allows one to properly identify and analyse each of its elements - people-centrism, anti-elitism, and popular sovereignty - in media articles (see March, 2017).

In fact, the focal point of this research is placed on the media’s approach to this concept, as “most scholars tend to neglect the perspective of the users of the term” (Hamo, Kampf and Weiss-Yaniv, 2018, p. 2): what meanings do media outlets attribute to populism or populist actors? In spite of a scarce set of empirical results - usually limited to single countries for short periods of time -, evidence presents some common patterns on the topic. Bale, Van Kessel, and Taggart (2011, 111) undertook the first study of the kind and sought to examine “the popular - or vernacular - usage [of the term] and to see how it relates to that academic debate”. By focusing on print media in the United Kingdom, the authors observe that the word is mostly used with a pejorative connotation, as well as with little criteria - it describes a wide range of actors and geographical contexts (Bale, Van Kessel, and Taggart, 2011, pp. 127-129). Interestingly, populist appears more than populism, suggesting the term to be essentially used to characterise political actors, parties, or policies (Bale, Van Kessel, and Taggart, 2011, p.117).

Its prevalence within tabloid newspapers divides the empirical literature (cf. Akkerman, 2011), but the dominant use is verified in news and opinion articles, as opposed to letters to editors, readers’ comments and other non-journalistic articles (see Herkman, 2016, p. 153), and it entails a mostly negative view, essentially aimed at positioning other parties (Hamo, Kampf and Weiss-Yaniv, 2018). Moreover, it must be noted its association with the ideological features of nativism, nationalism, and xenophobia (Herkman, 2016; cf. Herkman, 2019). Nonetheless, when focusing the analysis on the longitudinal evolution of populist discourses on media, the evidence seems to suggest that media do not follow the levels of populism in party manifestos or its own electoral growth and prominence (Bos and Brants, 2014; Manucci and Weber, 2017).

Regarding the case of Portugal, an analysis of the extent of populist discourse in Portuguese traditional and online media reveals only a minimal presence of populist typical elements (Caeiro, 2020; Salgado, 2019), which might have contributed to the Portuguese initial immunity to populism (cf. Salgado et al., 2021). In addition, populism is mentioned with hostility, and it is

equated with simple-mindedness, lack of sophistication, and an overly emotional and moralistic approach to politics. Populism is also viewed as dangerous, leading ultimately to the weakening of democracy and its procedures and institutions, and favouring personalistic and plebiscitary political regimes. [Salgado and Zúquete, 2016, p. 242]

Particularly, it is often associated with radical- or extreme-right discourses and parties such as the National Renewal Party (PNR), but also CDS-PP. Additionally, it is also linked to political leaders, namely local and regional politicians such as Valentim Loureiro, Fátima Felgueiras, Isaltino Morais, or Alberto João Jardim (Salgado and Zúquete, 2016, pp., 236-240).

All in all, despite constituting an exploratory paper, some theoretical expectations might be drawn from the literature. Considering the time period in analysis, one could expect populism to be increasingly visible in media articles throughout the 2010s, by and large, introduced in a negative way. Furthermore, empirical evidence suggests that these mentions tend to be mostly associated with far-right political parties and politicians. In Portugal, however, its exceptionality might lead to two nuances: on the one hand, a greater number of mentions of an international context; on the other hand, a higher focus on individuals instead of parties, as radical right parties exhibited little electoral weight until the emergence of Chega, in 2019.

Data and methodology

The analysis consists of evaluating the use of the terms populism(s) and populist(s) in Portuguese media for a period of ten years (2012-2021), as it covers the concept’s meaning before and after the demise of Portugal’s so-called exceptionalism. Hence, an original database was created by collecting mentions of populis* in print media. The option of resorting to this type of media lies in the advantage of relying on a single source for capturing the discourse of journalists, politicians, and the public (Bale, van Kessel and Taggart, 2011, p. 116). Furthermore, this approach offers a more in-depth examination of content through text analysis and allows the disentanglement of distinct patterns pertaining to the authors, genres, or sections.

The dataset relies on two Portuguese quality media outlets: Público and Expresso. Whereas the former constitutes a daily newspaper, the latter is published on a weekly basis. Thereby, a few disparities might be found in their criteria for determining newsworthiness, potentially affecting the coverage of certain actors or events. Moreover, in spite of the reduced media political bias (cf. Pereira, 2015), Expresso has been noted to present a moderate level of partisanship towards the centre-right PSD; conversely, Público tends to align more closely with the left-leaning PS (Popescu et al., 2013). Despite limited, these ideological distinctions may be of relevance to comprehending the framing of specific political actors.

Furthermore, data collection complied with the following rules: regarding Público, data selection included 10 random editions for 6 months (odd months in even years and vice versa); for Expresso, data selection considered all editions in the same exact months under analysis. All sections were considered for coding, as well as any genre. Overall, this led to a total of 1 095 valid mentions - 583 mentions belong to Público and Expresso has 512 references. This corresponds to a sum of 931 analysed articles and 502 editions with valid mentions (see Table 1).

The unit of analysis corresponds to different substantial mentions for populis* per piece of news. By substantial mentions, one refers to populist(s) or populism(s) as substantially labelling political actors, institutions or policies, as well as their attitudes or discourses (e. g. the leader spoke with a populist rhetoric); or describing it as a phenomenon (e. g. the emergence of populism is a threat to democracy). As it is outside of this scope, coding does not include negative (e. g. she is not populist) or hypothetical (e. g. he could have been a populist leader), as well as sarcastic or ironic sentences. These mentions must also be in text: when populis* appeared solely in the article’s title, it was not considered.

The same article may contain several mentions, and the usage of the term may vary in clarity. Thereby, these mentions can be explicit or not (e. g. the crisis is fostering the emergence of populism, or the crisis is fostering the emergence of the populist party X). Moreover, it must be noted that the same substantial mention (e. g. the populist leader Y) may be referred to multiple times in the same article while being coded just once - for example, an article that specifically addresses the populist leader Y may use the root word populis* for a significant amount while referring to the same political actor. In addition to mitigating the risk of overweighting particular actors, events or policies, this approach also fosters a deeper understanding of the meaning of each substantial mention.

Table 1 Descriptive summary of the number of mentions, articles, and editions covered by the dataset.

* Values in parentheses refer to the total number of editions covered by the dataset. ** Calculation considered the total of articles with valid mentions. *** Calculation considered the total of editions with valid mentions.

Data coding was organised into three sets of variables. While the first one includes information on the articles’ edition, the second set of variables comprises data on the piece of news itself. Then, the content level of analysis pertains to the connotation, context, framing, and the object being qualified, as well as any attributes associated with populism. The Codebook detailing all the criteria and guidelines for data collection is provided in the Appendix.

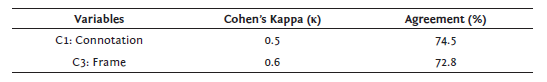

Coding was performed by one of the authors. To ensure reliability, a random sample of 64 editions was coded by an external coder. This sample corresponds to 5% of the total number of editions containing valid mentions to populis* (N = 502) and is stratified in accordance with each newspaper’s relative weight in the set. Considering the most common statistical measure for assessing inter-coder reliability, variables connotation (C1) and frame (C3) have respectively registered a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.5 and 0.6, along with agreement percentages of 74.5% and 72.8%. Results are thus generally acceptable (see Table 2 below).

Access to data was possible due to online available archives (Público, 2012--2021; Expresso, 2015-2021) and print editions (Expresso, 2012-2014), consulted at the periodical archive of the National Library of Portugal.

Breaking (the) news? Populism on the portuguese press (2012-2021)

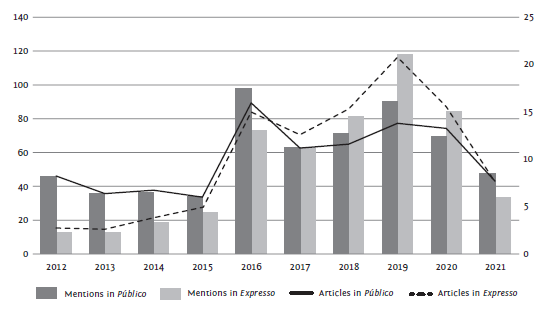

The analysis covers the most intensive years of bailout (2012-2013) and Chega’s entry into parliament (2019). Nevertheless, a longitudinal review of the articles and mentions of populism emphasises two pivotal moments: 2016 and 2019 (Figure 1). All in all, Público and Expresso present similar longitudinal patterns, as main disparities are only noticeable in terms of dimension: Público achieved its highest figures for mentions and articles in 2016, and Expresso attained its peak numbers in 2019. In fact, Público registered a higher number of mentions and proportion of articles from 2012 to 2016, but the trend inverted after 2017 with Expresso leading in both mentions and proportion of articles. As this finding might derive from editorial criteria, further analysis of genres, sections and themes may enlighten it.

The peak of 2016 is mostly defined by the US Presidential Elections, as Donald Trump (N = 27) was portrayed as a significant threat. Interestingly, populism was also minimally associated with left-leaning candidate Bernie Sanders (N = 2). In turn, Brexit received minimal attention (N = 2), with its key actors - the UK Independence Party (UKIP) and Nigel Farage - garnering just one mention. This might be attributed to the perception of the referendum as a symptom of populism’s growth rather than an inherently populist event.

The notable number of mentions in 2019 (N = 215) may relate to the populist uprising in Western European national elections and cabinets, as seen in Italy and Spain. Notably, Movimento 5Stelle (M5S, N = 10), Lega (N = 5), and Matteo Salvini (N = 8) received significant attention. Podemos and Unidas Podemos (N = 10) had a relevant number of mentions as well, whereas Abascal (N = 1) and Vox (N = 1) had surprisingly less visibility, possibly due to its recent electoral growth. In Portugal, this year marked the emergence of Chega (N = 10), but its leader, André Ventura, was only mentioned twice.

In opposition, 2020 and 2021 registered a sharp decline in these numbers, possibly due to the increasing coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, figures are still superior to those from 2012 to 2015 (Figure 1). This might suggest that populis* was more strictly employed at the time, before its generalised emergence in Europe. Overall, a first finding could thus indicate that the term is predominantly associated with foreign events and actors.

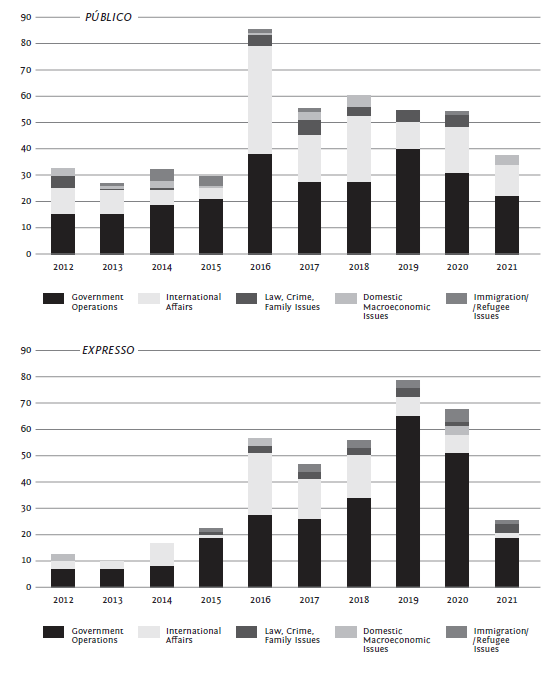

In fact, this is partially acknowledged by looking into the newspapers’ sections, as “International” has a significant proportion across this time scope for both Público (N = 126) and Expresso (N = 133), generally surpassing the sections of “Highlights” and “Politics” (Figure 2). Whereas “International” registered a slight increase for both newspapers from 2015 to 2019, its weight is superior within Expresso. In turn, “Politics” exhibits a modest increase in 2018 and 2019, possibly accounting for the emergence of Chega. Overall, op-ed sections are the most prevailing ones: “Espaço Público” (Público) and “Opinião” (Expresso) add up to 262 and 202 mentions, respectively.

Figure 2 Diachronic evolution of the number of mentions according to the section and genre, 2012-2021.

Nevertheless, the main disparity is visible within op-ed pieces. After 2016, Público consistently features a widespread prominence in this genre, with articles maintaining a stable median value. Conversely, articles in Expresso experience a notable growth between 2017 and 2019, possibly driven by the growing significance of the “International” section. During this time, articles have become the predominant textual genre.

This analysis sheds an interesting light on the use of the term, as it is seen as mostly used in pieces that present an individual’s point of view on a given subject. It thus means that referring to populism in the press is often not bound by the assumed impartiality of an article, leading to a careless use of the term. Indeed, op-eds register modest figures for explicit mentions, particularly in Expresso (see Table A1, Appendix). The following examples illustrate the wide range of its usage, mainly spanning from describing a threat linked to far-right politics that undermine liberal democratic values to a form of politics designed to appeal to the electorate:

Populism expresses itself in many different ways, some of them totally unexpected and, at first sight, sensible. This is its greatest danger and its most harmful aspect for democracy […] [.] Fortunately, in Portugal and despite the extreme difficulties we are going through, the most radical populism, such as that which manifests itself in Northern Europe, France or Italy - and which is expressed through nationalism and all kinds of prejudices towards the other - still does not have a relevant or even organised expression. Of course there is another form of left-wing “populism”, which today the CGTP interprets perfectly and which is equally dangerous. [Sousa, 2012]

At the time, it was much easier to give in to demagogy and populism and to call for less rigour in public accounts or to call for confrontation with our creditors, especially our European partners. [Montenegro, 2018].

Moreover, it can be said that most mentions are authored by or cited from non-politicians (journalists, columnists, or experts): in Público, this proportion is 76.2% (N = 414), while Expresso amounts to 78.8% (N = 395). Nonetheless, a significant sum of mentions still originated from political actors, either by authoring articles or being directly or indirectly cited by journalists, indicating that these also have a relevant role in bringing the term into the political sphere, often as a form of disqualifying political opponents. When compared to journalists, politicians are also suggested to provide fewer explicit mentions, as well as less aligned with scholarly classifications (Table A1). In other words, this suggests that political actors as “claimants” often lend themselves to a more subjective and unclear use of the term, with no concrete meaning.

For both Público (95.1%, N = 543) and Expresso (97.9%, N = 501), mentions of populism primarily carry any form of political relevance. This is translated into the topics in which populism is mentioned, as “Governmental Operations and Political Affairs” and “International Affairs and Foreign Aid” constitute the large majority of those (Figure 3), leaving little room for other subjects and thus suggesting that it is mainly associated to a prevailing political context rather than specific policy domains. Indeed, this is also reinforced by looking into the specific issues most addressed by the pieces: “Elections” (19%, N = 177) and the “European Union” (10.3%, N = 96).

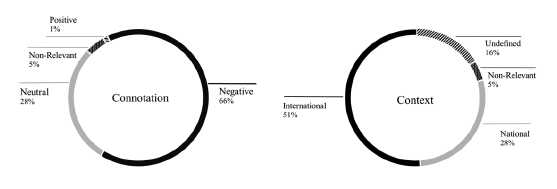

Show don’t tell: content analysis

Data analysis shows that, for the period under study, the connotation of the referent mentioned as populis* was mainly negative (Figure 4), accounting for 66% of all valid mentions (N = 725).

The term populis* was frequently used in these years to describe international contexts (Figure 4), particularly in the political contexts of the US, Spain, and Italy. Longitudinally, the prominence of negative mentions in 2016 and 2019 (Figure A1, Appendix) is linked to the historical context in which the analyzed pieces were produced. In the international news, the analysis covered 46 countries, both in Europe and Latin America. Interestingly, in 2020 ( Figure A1), populis* was primarily associated with a national context, accounting for 51.4% of total mentions that year (N = 73 out of N = 142). This shift may be attributed to the emergence and subsequent electoral success of the Portuguese populist party Chega in the 2019 general election, which resulted in André Ventura, the party’s leader, securing a parliamentary seat.

The haziness around the concept of populism may lead to very different framings around what populism is and who or what can or shall be defined as populist. Nevertheless, our data unveils a pattern (Figure 5): when the root word populis* was employed by the Portuguese press, it was mainly used to describe “Individuals” (45.7%, N = 188) and framed as “Ideology” (57.4%, N = 236). When employed to signal individual political actors (i. e., politicians or political party leaders), populism frequently referred to the ideological standings or positions of the actors (29.4%, N = 86), as well as to the more performative elements related to their discourse and style (49.5%, N = 93). In turn, regarding political parties, populism was foremost used to describe their ideological standings (72%, N = 144). Unsurprisingly, thus, the portrait of populism drawn by its usage in media outlets remains essentially bound to individual political actors and their exceptional personalistic traits or communication styles. The following example illustrates how populism was used in the same piece under different framings to refer to the ideological standing of Chega (political party) and the discourse of former Portuguese prime minister and president Aníbal Cavaco Silva (individual):

There is a kind of reluctance in saying what Chega is. Some readers have protested against the use of the “extreme right” label. Others say it’s “just populist” […] [.] André Ventura made his way, with the help of Pedro Passos Coelho, the PSD and Correio da Manhã television, and made it to Parliament […] [.] Is Ventura a populist? We can say that. But if in the 1980s Cavaco Silva had a “national and populist” discourse, as is now widely agreed, to say that Ventura is a “populist” is not enough. [Reis, 2019].

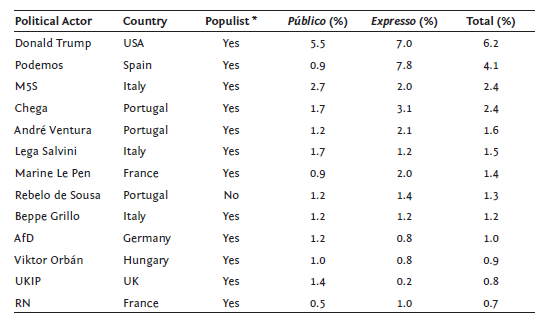

Regarding specific political actors, prominent individuals and parties consistently align with the longitudinal patterns described above, a trend that is exhibited by both newspapers. For instance, Donald Trump garners the most attention (6.2%, N = 68), followed by relevant populist political parties in Western Europe (Table 3). In the wake of the respective national elections, these comprise Spain’s Podemos and Italy’s M5S (as well as its founder, Beppe Grillo) and Lega Salvini. Nevertheless, additional key populist parties in Europe are also considered here, namely the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Germany), the Rassemblement National and its leader, Marine Le Pen (RN, France); and the UKIP (United Kingdom). Orbán, a populist leader in power, also receives notable coverage in the Portuguese press.

Conversely, Portuguese actors are modestly present amongst the most mentioned ones. As expected, Chega (2.4%, N = 26) and André Ventura (1.6%, N = 18) constitute the most stressed figures, followed by Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, the Portuguese president (1.3%, N = 14). However, whereas Ventura leads a radical right populist party that assumes a restrictive view of the people, Rebelo de Sousa is extensively referred to as featuring populist elements due to its close proximity to Portuguese citizens.

In fact, the extensive focus on Rebelo de Sousa stands in contrast to the general alignment between the media and academic conceptualisation of populism. Concerning the figures that are mostly mentioned in the Portuguese press, media is suggested to chiefly follow scholarly definitions. Moreover, 64.3% of all mentions (58.4% for Público, 70.7% for Expresso) are aligned with extant and reliable classifications of populist actors. Thereby, contrary to initial expectations, populism does not appear to be applied with little criteria.

This finding holds for both Público and Expresso, and newspapers’ ideological affinities are not argued to play a role in presenting political actors as populists. Most of them are similarly covered by both outlets, with the sole exception of Podemos - the party is highly stressed by Expresso, in contrast not only with Público but also with the remaining political figures.

Mentions with a positive tone are near-negligible, and the connotations are largely similar, even though Expresso displays a greater propensity to neutrality (Table A2, Appendix). Moreover, while no robust and regular patterns are unveiled in regards to their connotation, one might nevertheless note that inclusionary populist parties (i. e., focused on socially and politically marginalised citizens; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2013) - Podemos and M5S - are consistently presented with a neutral tone, as opposed to most exclusionary populists (aligned with nativist or nationalist stances). Overall, disparities amongst newspapers are not suggested to drive further differences in covering and qualifying political actors as populists.

Table 3 Most mentioned political figures and parties, per newspaper.

* Populist classifications are drawn from extant scholarly operationalisations, namely the PopuList (Rooduijn et al., 2019) and Populism in Power Around the World (Kyle and Gultchin, 2018).

Lastly, despite their meaningless visibility, public policies entail a set of proposals (N = 56) that is quite diverse, accounting for several single mentions that are often unclear per se or related to specific political events. In spite of not encompassing an exhaustive assessment, a comprehensive analysis might identify some common - yet contradictory - trends that entail social and political goals. On one hand, populism is not only related to social measures that increase the state’s expenditure, such as abolishing university tuition fees or reducing housing prices but also to typically liberal ideas, such as privatizing companies or reducing taxes. On the other, it also points to nationalist and authoritarian political aims, by aiming to build border walls or referending the European membership, as well as reinforcing the executive power or restricting media and judicial freedom. Moreover, an anti-elitist stance is also visible in policies described as populists, covering the restriction of politicians’ privileges and consecutive office terms, the decrease of parliamentary seats, or the election of parliamentary empty seats.

Finding a meaning: disentangling the features of populism

Mentions to the root word populis* are scarcely followed by concrete references to populism’s ideological elements: whereas people-centrism and anti-elitism present modest figures (6.8%, N = 74, and 7.6%, N = 83, respectively), popular sovereignty is near-negligible (2.0%, N = 22). In addition to this, only nine mentions exhibit all three dimensions simultaneously.

This might suggest that populism is mainly related to radical and extreme ideological stances. On the one hand, far-right elements such as nativism, xenophobia and racism (13.8%, N = 151), or nationalism (3.5%, N = 38) are prevalent, with mentions of the far-right-wing as qualifying a political discourse or actor being also visible (1.8%, N = 20). These features add up to approximately 20% of valid mentions, in line with the literature (cf. Salgado and Zúquete, 2016). On the other hand, far-left attributes hold less weight, constituting only 4.6% (N = 50) of valid mentions. Overall, this stresses the idea that populism in the media is significantly associated with exclusionary populism, namely its rise in Europe during the 2010s (cf. Vittori, 2022).

Secondly, populism is also highly regarded as demagogic and linked to simplistic or unfeasible policies. This characteristic accounts for 8.2% of this data (N = 90) and examples are diverse, following no clear or common reasoning. These include proposals like introducing universal basic income and advocating for constitutional reforms such as reducing parliamentary seats.

Thirdly, populism’s negative portrayal is closely linked to its deemed impact on (liberal) democracy. This finding adds up to the figures of the mentions that perceive populism as negative by providing further insight. Whereas 4.6% (N = 50) of valid mentions see populism as a threat to liberal values, associations with authoritarianism (0.9%, N = 10), misinformation (1%, N = 11), and Euroscepticism (0.9%, N = 10) have a minor role. Anti-system (1.8%, N = 20) and anti-establishment (1%, N = 11) are also used to qualify populist actors, discourses, or ideas.

Lastly, stylistic elements are also associated with populism, albeit to a lesser extent. Particularly, the pieces minimally link populism to strong leaders holding central roles within their structures and a charismatic public presence (1.1%, N = 12). They also regard populism as encompassing a loosely mediated relationship to the people (0.6%, N = 7), as well as a popular and simplistic language or style (0.5%, N = 6).

Discussion and conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this paper consists of a first attempt to examine the concept of populism and its meaning in the Portuguese press. In light of populism’s growing prominence in the public sphere, the use of media data becomes of paramount importance to disentangle the actors, contexts, and frames shaping the meaning of the concept. While its aim is primarily descriptive and exploratory, the examination of a set of theoretical expectations presents some features that might be of interest. In general, findings seem to align with these: the concept of populism gained significant prominence in the press during the 2010s, predominantly marked by international references and a negative connotation, often intertwined with far-right politics. However, despite following the broader pattern of rising populism within the European political landscape, this association is not clear, and the term’s conceptual haziness is notorious. Overall, this study may lead to three main conclusions.

First, the exhibition of a predominantly negative connotation is in line with the scholarship on the topic. Populism is often applied as a critique that disqualifies other political players, while also serving as a reference for perceived threats to liberal democracy or irresponsible policies and events. On the one hand, the concept is highly linked to far-right politics, leveraging the idea that Portuguese media tends to emphasise nativist and nationalist frames in order to construct the meaning of populism (cf. Herkman, 2016). From our data, it seems safe to argue that, albeit with considerable exceptions, when used as an adjective following other ideological stances, populis* was often associated with right-leaning political ideologies. While this is visible in most features associated with the term’s mentions, it might also be regarded in the prominence of political actors. Despite the recent emergence, Ventura and Chega collect the highest number of mentions covering the Portuguese context. In turn, on the international stage, references to populism predominantly involve actors such as Trump, Le Pen, Orbán, or Salvini, as well as their respective political parties.

On the other hand, populism may equally be perceived as fitting the frame of an empty rhetoric, through a down-to-earth rhetoric or irresponsible policy-making (Herkman, 2016, p. 152). This is suggested by the great weight of associations to demagogy. As it is mainly aimed at undermining other political actors, this feature is considered with little consistency by covering a wide range of politics and politicians. Consequently, it also includes political actors that are not deemed as populists by the academic literature, such as Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, Rui Moreira (the mayor of Oporto), or the Socialist Party.

Secondly, we may also conclude that the vernacular use of the concept is often aligned with its academic formulation. This is not only illustrated by the main use of ideology as a framing, in line with most academic literature, but also by the classification of populist figures as so. Indeed, the prominent individuals and political parties mentioned by Público and Expresso regard the main populist leaders and parties in Europe and the United States. The sole exception is the recurrent reference to Rebelo de Sousa. Furthermore, the overall picture suggests that the media and the academic literature tend to agree in most mentions. All in all, contrary to expectations and in spite of not invalidating the wide and diverse range of political actors to be described as populists, these findings leverage the argument that media is substantially aligned with the academia. Nevertheless, the general use of the concept does not greatly mirror the main ideational traits of people-centrism, anti-elitism, and popular sovereignty: media frequently views populism as radicalism - mostly from right-leaning actors, but also from left-leaning ones, yet to a significantly lesser extent.

Finally, the use of the concept follows similar patterns for both newspapers. In fact, mentions in Público and Expresso identically display a significant sum of observations in “Opinion” sections and op-ed articles, possibly suggesting that the term is used with modest criteria. Most mentions are also found in articles addressing topics of political relevance, namely concerning governing issues. Additionally, mentions extensively stem from international actors and events, which account for the particularly high growth rates in using the term in 2016 and 2019. This greater focus on international subjects is suggested to come from the absence of populist political parties in Portugal with a significant electoral weight until the emergence of Chega. Furthermore, differences between Público and Expresso are also suggested not to play a significant role, as they largely agree in regards to the most covered actors and the tone these are referred to.

Despite its mainly descriptive nature, this study may open new avenues of research concerning the construction of the concept in the public sphere but also contribute to tracing the history of populism in Portugal by identifying objective political actors, policies, or events. In light of these precepts, some limitations must be accounted for in future studies. First, a less descriptive analysis is required to further explain the use of the concept, by resorting to qualitative interviews that inquire the authors on the implied meaning of populism; furthermore, it would be relevant to include tabloid newspapers in the analysis. Second, the time scope must also be extended in order to include the years preceding the European populist zeitgeist. Lastly, data collection might benefit from automated techniques that allow for more effectively building a rigorous dataset, by avoiding the imprecisions of manual coding.

Either way, the clarification of this term’s use within the public sphere is set as a research topic of significant relevance. The need for calling a spade a spade is also the need for not diminishing the concept of populism and the threat it may pose to liberal values and democracies.