Introduction

One of the primary challenges confronting contemporary democracies revolves around the increasing electoral support garnered by populist parties (e. g. Mudde, 2007; Kessel, 2015). A pivotal factor contributing to the success of these new populist parties, irrespective of their left-wing or right-wing orientation, is their ability to compete with other protest parties through mobilising abstentionists. Indeed, dissatisfied citizens may exhibit two distinct responses to their discontent with the political system. On the one hand, they may choose to disengage from the political system, effectively exercising what Hirschman termed the “exit” option. On the other hand, they may actively challenge established political parties by casting their votes in favour of a populist (or challenger) party, thereby giving a “voice” to their dissatisfaction. Consequently, abstention and populist voting may be intertwined; however, empirical research paints a complex and inconclusive picture of the relationship between these two phenomena. In many countries, a decline in voter turnout has coincided with the ascent of populist support.

Theoretically, abstention and populist voting have various points in common. First, both abstention and populist voting can be seen as a rejection of mainstream democratic politics or as a way of channelling anti-political sentiment or political resentment. From this viewpoint, the literature shows a significant overlap between the political attitudes associated with voting for populist radical right parties (PRRP) and abstaining (Allen, 2017). Second, abstention and the populist radical right vote are fostered by feelings of alienation, particularly when people believe that their interests and concerns are not sufficiently represented by the political elites. This phenomenon seems to be reflected by the low level of political efficacy of this group of voters.

Some studies compare abstainers and populist voters (Allen, 2017; Kessel, Sajuria and Hauwaert, 2021; Koch, Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2023; Leininger and Meijers, 2021; Zagórski and Santana, 2021), but there is a lack of consensus regarding the connection between the populist radical right vote and abstention, and the mechanisms behind it. Although the success of populist parties seems to go hand in hand with increasing levels of mobilisation in some countries, in others the relation is the opposite (Immerzeel and Pickup, 2015; Leininger and Meijers, 2021). Despite a growing interest in the topic, we still lack a clear picture of the connection between turnout and the populist vote.

To fully understand these two important phenomena that characterise contemporary representative democracies, it is necessary to analyse the individual factors that differentiate citizens who choose to vote for a populist party from those who choose to abstain. Accordingly, this paper aims to examine the factors that discriminate those who remain loyal to established parties, supporting them with their vote, from those who choose to abstain and those who opt for populist alternatives. To accomplish this, we direct our attention to Portugal, a country where the radical populist right was virtually non-existent in the political landscape until quite recently. Concurrently, Portugal has experienced a noticeable upsurge in abstention rates. This unique juxtaposition makes Portugal a particularly compelling case study. Historically, the Portuguese context was regarded as an “island of stability” amidst the backdrop of escalating electoral volatility and party system fragmentation witnessed across Europe (e. g. Carreira da Silva and Salgado, 2018; Lisi and Borghetto, 2018). This was quite remarkable since Portugal did not experience major changes in party system features and government dynamics during and after the Great Recession, unlike other Southern European countries (e. g. Jalali, 2019; De Giorgi and Pereira, 2020). Despite this, new parties emerged and gained parliamentary representation, especially after the 2019 parliamentary elections. The most successful new player was the populist radical right party Chega, which achieved the third position in the 2022 legislative elections, gaining 7.2% of the vote. This was an astonishing result in the Portuguese context, as the party had been formed just three years earlier and elected its first MP in the 2019 legislative elections with 1.3% of the vote. Moreover, this was not an epiphenomenon, as Chega obtained 18.1% of the vote in the 2024 elections, suddenly forming a third pole in the Portuguese landscape. This sudden and significant increase not only affected the Portuguese party system but also projected the party at the international level, becoming one of the most recent cases of success within the populist radical right party family in Europe.

This study seeks to offer two significant contributions. Firstly, it investigates the common characteristics shared by two distinct groups of citizens: non-voters and supporters of the populist radical right. To the best of our knowledge, it represents the most comprehensive examination of the disparities between mainstream party voters on the one hand and abstentionists or populist supporters on the other. Secondly, it contributes to the current body of literature by investigating a less-explored case, Portugal, that holds growing significance within both the national and European contexts. This examination enables us to refine conventional wisdom, scrutinise established and emerging hypotheses, and expand the comparative analysis of populist voting.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows: In the second section, we review the literature on the characteristics of the populist electorate and non-voters and we derive the main hypotheses related to the Portuguese case. The third section deals with methods and data, while the subsequent section presents the empirical analysis. The conclusion summarises the main findings, discusses the implications and suggests some fruitful avenues for future studies.

Voting for populist parties and abstention as two ways of channelling discontent

There are few phenomena in the field of political science as extensively documented as the decline in voter turnout in advanced democracies. This trend has been linked primarily to structural shifts within our societies. Long-term factors, such as the weakening of political parties, the process of disintermediation, and a growing sense of mistrust towards representative institutions are the conventional explanations for this phenomenon. However, it is essential to recognise that abstention is a multifaceted phenomenon that can also be influenced by both contingent and strategic factors.

The short-term and circumstantial aspect of abstention is closely tied to political considerations, including the assessment of specific leaders, campaign agendas, and the competitiveness of elections. In essence, abstention often manifests itself in two distinct forms: one associated with “apathy” and another with “protest.” The dimension of protest within abstention provides fertile ground for the mobilisation of new political parties, particularly populist parties that resonate with dissatisfied voters and adopt anti-establishment rhetoric.

Not surprisingly, extant scholarship that focuses on the connection between these two phenomena presents different views on the topic. According to one strand of research, abstentionism and support for populist parties have been understood to function as communicating vessels. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (2017, p. 83) state that “populism tends to favour political participation.” Populist movements and parties stand to voice the concerns of citizens who have previously been misrepresented or underrepresented by the political establishment. These authors therefore hypothesise that the existence of populist parties in a given political system may increase voter turnout in national elections. From this viewpoint, populists (both left and right) seem to be better positioned than their established counterparts to mobilise abstentionists (Leininger and Meijers, 2021).

However, we can also find arguments according to which the logic of action for electoral participation is distinct from that of populist voting. From this perspective, abstention is often viewed as a form of protest against the political system (Ekman and Amnå, 2012), whereas populist voting directs criticism at mainstream parties (Hartleb, 2015). A study conducted in Chile by Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser (2019) revealed that populist voters encompass a heterogeneous group in terms of political engagement. Some are politically interested and active participants, while others are characterised by apathy, disinterest in politics, and a rejection of all political narratives, including populism. Consequently, this group of voters disengages from political discourse and ends up disconnecting from politics through abstention. The populist segment of the electorate also consistently differs from mainstream voters, who demonstrate unwavering loyalty to the principles of the liberal democratic regime, actively participate in elections, and align with established political parties.

Inconsistent findings also emerge when considering Western and Eastern European countries. In the former, populist voters tend to exhibit higher levels of political engagement, while the reverse holds true for the Eastern region (Immerzeel and Pickup, 2015).

Several reasons might account for these contradictory results. First, some of these studies include distinct types of populist parties, from both the left and the right. Second, empirical research differs in the methodological strategy, as some works use aggregate data while others are based on individual-level data. Third, the geographical focus of empirical research also differs, looking at distinct case studies or regions. Therefore, this paper contributes to clarifying the debate by examining an underexplored case and focusing on the most relevant type of populism, namely radical right-wing parties. Moreover, this work takes a more comprehensive approach by systematically investigating how abstentionists and populist radical right voters differ. We are not only interested in the way populist voting and abstention share the same protest component but also to what extent these two phenomena differ (or not) in terms of other social or cultural traits. Next, we dig deeper into these two (partially) distinct fields of research to elaborate our main hypotheses.

Explaining differences and commonalities between abstention and populist voting: hypotheses

We start our review of the factors that drive abstention and populist support by examining the role of political interest. A consensual finding in the scholarship is that interest in politics is a motivational prerequisite for political participation (e. g. Carpini and Keeter, 1996; Gallego, 2015). This also applies to the Portuguese case (see Cancela and Vicente, 2019; Viegas and Faria, 2007). However, the picture is not so clear when it comes to the populist electorate. Populist voters are often portrayed as apathetic, low-interest protest voters and uninformed about political developments (Schumacher and Rooduijn, 2013; Brug, Fennema and Tillie, 2000). Nevertheless, there are also studies suggesting that populist voters, both left and right, are not necessarily politically apathetic but show higher levels of interest in politics than other voters (Hauwaert and Kessel, 2018). This means that citizens who are more involved in politics are also more likely to support populist forces. Thus, support for PRRP may be a sign of intentional choice on the part of politically informed, interested, and effective citizens (e. g. Eatwell, 2003, 1998).

In essence, a key distinguishing factor between voters of the PRRP and abstainers hinges on their level of interest in politics. In light of this, we posit that individuals who harbour a genuine interest in politics are more inclined to cast their vote in favour of the PRRP, much in the same manner as their non-populist counterparts. Conversely, individuals with lower levels of political interest are more likely to opt for abstention. Empirical findings from the Portuguese case further underscore a striking disparity between voters and non-voters in terms of cognitive mobilisation. Consequently, we anticipate that the distinc tions between supporters of populist parties, on the one hand, and non-popu list voters, on the other, may not be particularly pronounced.

H1A. Citizens voting for a populist radical right party will exhibit a comparable level of political interest to that of voters supporting non-populist parties.

H1B. Citizens with lower levels of political interest are more likely to abstainthan to vote for non-populist parties.

In the European context, citizens who trust their political elites and are more satisfied with democracy have been found to have a higher propensity to vote in elections (Grönlund and Setälä, 2007; Hadjar and Beck, 2010). Similarly, dissatisfaction with politicians and the political system is associated with the electorate of populist parties, especially those of the radical right (Betz, 1993; Fieschi and Heywood, 2004; Ignazi, 2006; Norris, 2005). Numerous studies indicate that the electorates of radical right populist parties show high levels of political distrust (Lubbers, Giijsberts and Sheepers, 2002; Ignazi, 2006: 213; Oesch, 2008; Hooghe and Dassonneville, 2018; Voogd and Dassonneville, 20120; Norris and Inglehart, 2019). While empirical research on the Portuguese case confirms the positive association between satisfaction with the political system and turnout, there are no studies dealing with populist support. Consequently, we posit the following:

H2A. People with higher levels of dissatisfaction towards the political system tend to vote for populist radical right parties rather than non-populist parties.

H2B. People with higher levels of dissatisfaction towards the political system are more likely to abstain than to vote for non-populist parties.

In contrast, political dissatisfaction and negative attitudes towards the political system relate to anti-elitism, which is one of the key components of populism. Empirical research on Western Europe shows that populist attitudes are strongly related to support for populist parties or leaders (e. g. Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro and O’Flynn, 2021; Spierings and Zaslove, 2019). This is also the case in Portugal as people who display higher levels of populist feelings are more likely to vote for Chega (Heyne and Manucci, 2021). On the other hand, the people-centric nature of populist politics can be particularly motivating for individuals who not only express dissatisfaction with the political system but also perceive a sense of disadvantage and exclusion from political life (Panizza, 2005, p. 16), because they may identify themselves as “the people.” However, even though populist attitudes are expected to be positively related to the probability of participating in elections, Anduiza, Ginjoan and Rico (2019) find that populist attitudes are linked to non-electoral forms of political participation, but not to turnout. Also in the Portuguese case, empirical research indicates that there is no relationship between populist attitudes and the propensity to vote (Santana-Pereira and Cancela, 2020). Therefore, we expect populist sentiments to be positively related to support for the populist radical right, but not to turnout.

H3A. The higher the level of populism, the more likely citizens will vote for populist radical right parties as opposed to non-populist parties.

H3B. Populist attitudes are not expected to have a significant impact on abstention.

It has been shown that both voting for populist parties and abstaining from electoral participation are connected to evaluations of the political system and the performance of political elites. However, citizens’ perceptions of how political influence can be exerted through participation in the political process differ (Henjak, 2017). The impact of populism on political engagement is not static but varies depending on the available avenues for political action. This implies that populist voters may attribute different meanings to conventional and unconventional forms of participation compared to non-populist voters. Recent research suggests that citizens displaying populist attitudes are more inclined to engage in unconventional modes of political participation than voters with non-populist opinions (Anduiza, Guinjoan and Rico, 2019; Pirro and Portos, 2020). However, when it comes to participating in political actions that entail potentially high costs, such as street demonstrations, the evidence is mixed and often varies by country (Anduiza et al., 2019), or may not be consistent across different contexts (Pirro and Portos, 2020). From this standpoint, given that populism aims to mediate between “the people” and the “elite” in the struggle for political influence and has a penchant for embracing an “anything goes” approach toward institutional democracy (Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017), we expect that supporting the idea of people engaging in unconventional political actions - i.e. when they come with high costs like street demonstrations -, may lead individuals to support populist parties rather than voting for non-populist forces. As for abstention, it is plausible that individuals who are inclined to participate in unconventional forms of political engagement are also more likely to be mobilised to cast a vote. While we may not possess empirical evidence specific to the Portuguese context, we find no compelling grounds to dismiss conclusions drawn from research conducted within European democracies. Consequently, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4A. The greater the value granted to street demonstrations against institutional politics, the more likely citizens will vote for a populist radical right party.

H4B. The greater the value granted to street demonstrations against institutional politics, the greater the propensity to participate in elections.

We also know that voters constitute a specific sociological group that tends to be more exposed to politics in the media and to be more socially integrated (e. g. Barnes and Kaase, 1979; Hastings, 1956). Indeed, conventional wisdom on voting behaviour indicates that there is a strong association between social integration and the propensity to exercise the right to vote. Empirical evidence also suggests a positive relationship between voting PRRP and levels of social integration. First, social trust can strengthen populist attitudes and protest feelings, thus boosting support for PRRP (Rooduijn, Burgoon and Elsas, 2016). Second, far-right voters rank higher on measures of social integration (union membership, self-reported social activity and interpersonal trust) than non-voters (Allen, 2017). As far as the Portuguese case is concerned, there are no studies that test this hypothesis directly, but previous evidence suggests that those displaying anti-globalisation feelings (i. e. lower levels of “perceived” social integration) are more likely to vote for the new populist party (Heyne and Manucci, 2021). Given the lack of robust empirical evidence, we stick to the “conventional” hypotheses.

H5A. The higher the level of social integration, the greater the probability of voting for a populist radical right party vis-à-vis non-populist parties.

H5B. The higher the level of social integration, the greater the probability of voting for non-populist parties vis-à-vis abstaining.

Moreover, populism is seen as a corrective for democratic representation (or lack thereof) as it manages to politicise issues not being addressed by established political parties, thus attracting disillusioned citizens (e. g. Rovira Kaltwasser, 2014; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017). In this way, political issues are important in explaining support for PRRP (Arzheimer, 2009; Rooduijn, 2018; Voogd and Dassonneville, 2020), in particular by opposing mainstream parties and trying to appeal to unrepresented voters (Koch, Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2023). By contrast, no evidence associates non-voters with specific political issues.

The existing literature on Western Europe concludes that voters for PRRP differ from voters for other parties and abstainers in their anti-immigration and Eurosceptic attitudes (Allen, 2017; Zhirkov, 2014). This observation aligns with the results of Zagórski and Santana (2021) for Eastern European countries, where the disparities between abstainers and supporters of radical right populist parties mirror the differences observed between populist and non-populist voters. Specifically, voters of PRRP tend to exhibit stronger anti-immigration and Eurosceptic attitudes compared to both abstainers and voters of other parties. On the other hand, recent research focusing on the German context suggests that populist radical right voters and abstainers vary across all dimensions of political conflict except immigration-related issues (Koch, Meléndez and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2023). While both groups generally share a stance against immigration, the consistency of this view is markedly higher among populist voters compared to non-voters. The Portuguese case seems to follow European counterparts, as anti-immigration feelings have a strong impact on the propensity to vote for the populist radical right (Heyne and Manucci, 2021). This is not surprising given the strong emphasis on Chega’s programmatic stances to nationalist principles and anti-immigration orientations (Mendes, 2021).

The positions on European issues are more ambiguous; pro-European stances are usually strongly related to mainstream parties, while Chega defends the right of each member state to veto decisions and is very critical of the performance of European institutions (Marchi, 2020, pp. 184-189). Consequently, we posit that the electorate of the populist radical right will display negative stances regarding both immigration and European integration.

H6. The stronger their anti-immigrant attitudes, the more likely citizens will vote for populist radical right parties as opposed to non-populist parties.

H7. The stronger their Euroscepticism, the more likely citizens will vote for populist radical right parties as opposed to non-populist parties.

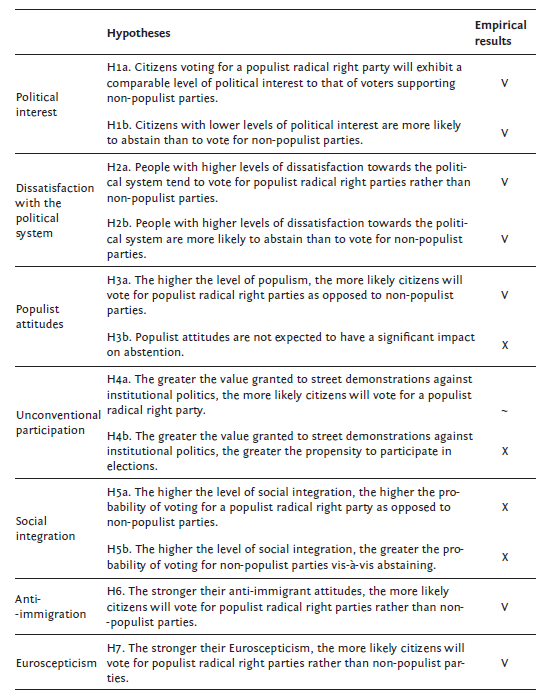

Table 1 summarises the main hypotheses that drive this research and advances the main results of hypothesis testing.

Data and methods

Portugal stands out in Western Europe for both its low level of turnout and the steady decline of electoral participation since the 1990s. Indeed, the proportion of voters has decreased from approximately 85% in the 1980s to the lowest score of 53% registered in the 2019 elections. We know that these abstainers do not all share the same characteristics (e. g. Freire and Magalhães, 2002). In fact, this is a heterogenous electorate, especially when we look at political attitudes. While a significant proportion of non-voters are outside the electoral market as they do not even consider the hypothesis of exercising the right to vote, strategic abstentionists - i. e. those who sometimes vote and consider the possibility of participating in national elections - have been on the rise. This electorate is particularly relevant not only because it can determine the electoral results, but also because it is one of the key targets of new political forces. Contrary to the “regular abstainers” group, strategic abstentionists present higher levels of involvement in the political sphere and a higher degree of cognitive mobilisation. They are also more sensitive to political supply, namely the issues discussed (and politicised) during the campaign and the profile of party leaders. A recent study on the 2019 elections found a significant association, at the aggregate level, between districts with higher levels of turnout and greater support for Chega (Lisi, Sanches and Maia, 2020). Although this can be a case of a spurious relationship, it is nonetheless worth delving into this subject and better exploring the connection between these two distinct phenomena.

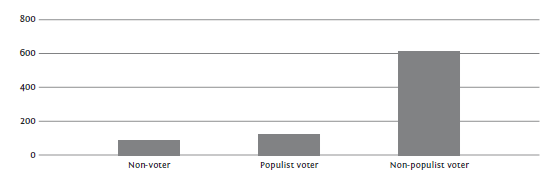

Our data (Ramos et. al, 2024) come from an original survey implemented online in Portugal by the company Netquest in September 2020, between the first and the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic.1 The survey was administered to 1055 individuals, but the final analysis was conducted over a sample of 805 individuals due to missing responses. For the dependent variable, we use the following question “If there were a general election in Portugal tomorrow, would you vote?”, and create a nominal variable consisting of three categories that distinguish between three participatory expressions: those who intend to abstain (1), those individuals who will cast a populist right-wing vote (2), and those casting a non-populist vote (3). Specialised literature and schemes of classification (e. g. Popu-list.org: https://popu-list.org/) have pointed out that there were no populist parties in Portugal until the emergence of Chega. As it is the only populist party in Portugal, the category “voting for a populist party” in our study means casting a vote for the new populist right party. Figure 1 provides an overview of the dependent variable’s distribution across the country. We note that while a significantly higher percentage of respondents said they would vote for a populist party (113), a minority of respondents said they would abstain from voting (82). This finding is somewhat unexpected, particularly in light of the 2022 elections when abstention rates reached as high as 48.81%, while Chega secured 7.18% of the total votes. It is essential to approach these results with a degree of caution, considering the potential influence of both the “social desirability bias” and “hidden abstention”. In other words, some individuals may claim to have voted for an anti-establishment force as a means of expressing their protest, which could lead to an underestimation of actual electoral participation rates.2

Figure 1 Distribution of vote intention: non-voters, populist voters, and non-populist voters. Source: Netquest survey (2020).

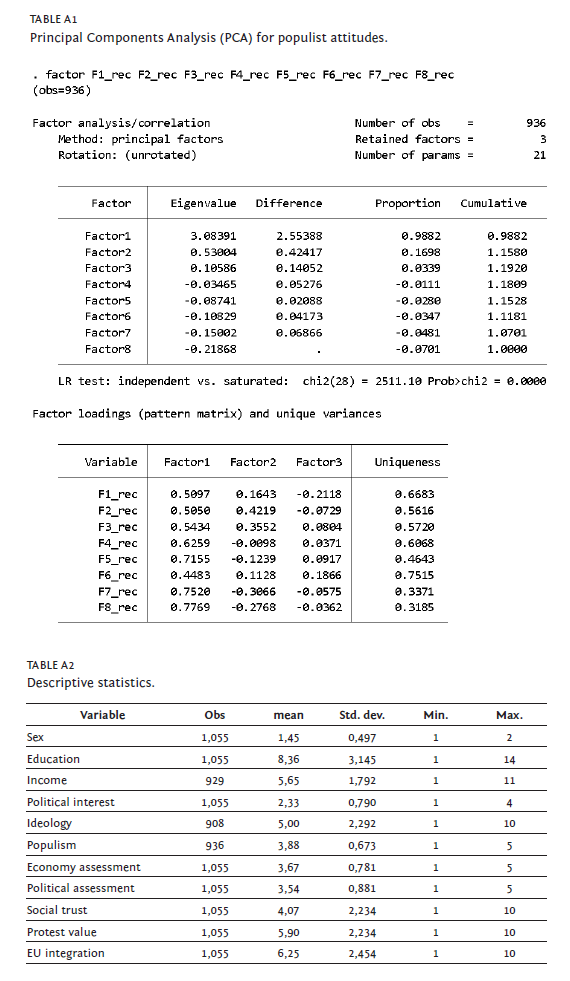

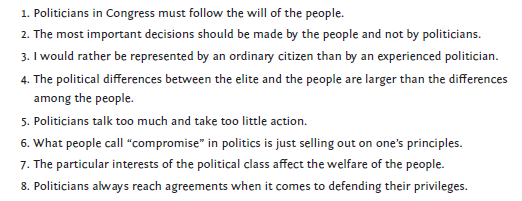

The key independent variables are intended to test the different hypotheses outlined above. Political interest (H1A and H1B) is captured by a scale ranging from 1 (“very interested”) to 4 (“not interested at all”). We use two different variables to test the second set of hypotheses related to dissatisfaction with the political system (H2A and H2B). In the absence of a better variable to tap the component of protest against the political system - as satisfaction with democracy or the evaluation of government -, we use the assessment of the general political situation through a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (“very good”) to 5 (“very bad”). In order to evaluate the populism hypothesis (H3A and H3B), we use the 6 items originally proposed by Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove et al. (2014, p. 1331) and two more proposed by Hauwaert, Schimpf and Azevedo (2020), in which respondents are asked to rate their agreement with each item on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“I very much disagree”) to 5 (“I very much agree”). A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is conducted to construct two factors with an Eigenvalue equal to or larger than 1 (see Table A1 in the Appendix), that correspond to the dimensions developed by the ideational approach to populism (Hawkins, 2019; Mudde, 2007).

Table 2 Items used to measure populist attitudes.

Source: Based on Akkerman, Muddle and Zaslove (2014) and Hauwaert, Schimpf and Azevedo (2020).

The hypothesis regarding the value granted to unconventional participation (H4A and H4B) is captured by a question in which respondents are asked to rate the value of street protests, ranging from 1 (“Policy should only be channelled through institutions”) to 10 (“It is good that people are taking to the streets in protest, even if it leads to riots”). We use an indicator of social trust to test the social integration hypothesis (H5A and H5B). Respondents are asked how far people can be trusted, responding on a 10-point scale, ranging from 1 (“Never careful enough”) to 10 (“Most people can be trusted”). To test the last set of hypotheses related to political issues (H6 and H7) we consider two variables. The first relates to “group preferences,” in which respondents are asked to rate their agreement with each item on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“I very much disagree”) to 5 (“I very much agree”). This variable is based on the different conceptions of citizenship and national identity and distinguishes citizens with exclusionary group preferences from those with inclusionary attitudes. We conduct a PCA that results in one factor aggregating four different items (from positive to negative attitudes towards immigration).3 The second variable refers to the “European integration” hypothesis (H7), which is tested thanks to an indicator coded through a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (“Integration has already gone too far”) to 10 (“There should be more integration”).

Sex (1 man, 2 woman), monthly income (from 1: I have no income of any kind to 11: more than €6000 per month), education (3 categories: less than primary, primary, and lower studies, upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary studies and tertiary education), and ideology (from 1: Left to 10: Right) are included in the model as control variables. Empirical research suggests that it is less educated people who tend to vote more for populist radical right parties (Lubbers, Giijsberts and Sheepers, 2002; Rooduijn, Burgoon and Elsas, 2017; Stockemer, Lentz and Mayer, 2018; Hauwaert and Kessel, 2018). These findings have also been confirmed when looking at the vote choice for Chega. Indeed, empirical research suggests that people with low levels of education are more prone to support the populist radical right party (Heyne and Manucci, 2021).

We run a multinomial logistic regression that uses the nominal variable measuring electoral behaviour as the dependent variable. Therefore, it distinguishes between voting for non-populist parties, abstention and voting for populists (three categories), while the vote for non-populist party category is the baseline of our model.4 We test two distinct models. The baseline model displays the correlation between the probability of voting for a populist party or abstaining (compared to the probability of voting for a non-populist party) and the following variables: gender, age, income, education, and ideology. The second model adds attitudinal variables, namely those independent variables that enable us to test the main theories discussed in the theoretical framework. All variables have been standardised before being included in the analysis.

Results

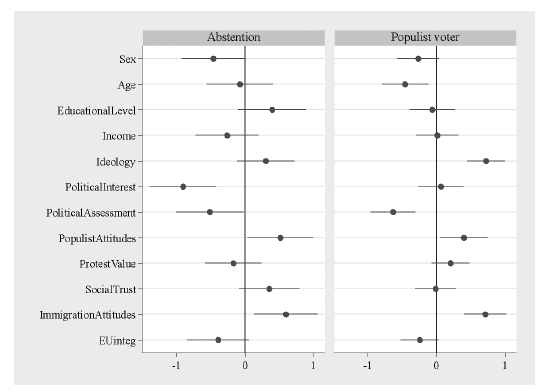

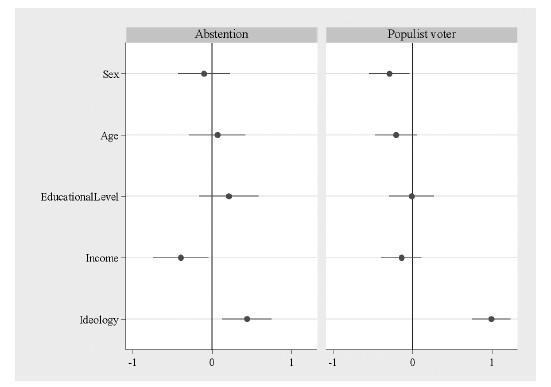

To support the discussion on how our expectations regarding the different factors explaining abstention and populist voting in Portugal line up with our findings, the coefficients of the multinomial regression model (with confidence intervals) are displayed in Figure 2 based on Table A4 in the methodological appendix.

Our findings reveal that ideology has a significant impact on both turnout and voting for PRRP. The coefficients indicate that right-wing voters are more likely to cast a vote for Chega and abstain compared to voters for non-populist parties, although the magnitude of the effect differs. The Average Marginal Effect (AME) analysis (Table A5 in the online Appendix) reveals that an additional point to the right in the ideological scale means a 2% increase in the probability of abstaining and an 8.9% of supporting the right-wing populist party, both over voting for a non-populist party. In addition there are differences in terms of socio-demographic characteristics. While income is negatively associated with abstention - i. e. higher socio-economic levels are more prone to vote for non-populist parties -, gender achieves statistical significance when we compare voters for populist parties with voters for non-populist parties. It is noteworthy that educational attainment shows no significant association with either populist voting or abstention. The absence of statistical significance in the coefficient related to the education variable is somewhat unexpected, especially considering prior research on populist parties and voter turnout. This outcome may be linked to the diverse composition of the primary groups within the dependent variable, encompassing individuals with various socio-demographic characteristics.

Figure 2 Multinomial logistic coefficients for the baseline model. Note: Dependent variable: 0 = vote for non-populist parties; 1 = abstention; 2 = vote for populist radical right party (Chega). Vote for non-populist parties is the reference category.

Moving to the second model, we can observe a significant increase in the variance explained, suggesting the relevant impact of key attitudinal variables (see Appendix, Table A6 and A7). We find a positive and statistically significant coefficient when testing the effects of political interest on abstaining instead of voting for a non-populist party (one additional point in the political interest scale means 2.4% less probability to cast a vote for a non-populist party); in contrast, there is a lack of statistical significance when considering voting for a right-wing populist party. This result reveals that, in Portugal, political interest increases the probability of voting instead of staying at home (H1B confirmed). It demonstrates that political interest is a relevant resource for mobilising citizens (Verba et al., 1995) and differentiates voters from abstainers. However, political interest does not discriminate voters for non-populist parties from populist supporters, which confirms H1A.

In line with our expectations, both radical right voters and abstainers exhibit higher levels of dissatisfaction with the political system when compared to non-populist party voters. This finding aligns with previous studies exploring the relationship between dissatisfaction with the political system and populist voting behaviour (Hooghe and Dassonneville, 2018; Ignazi, 2006; Lubbers, Giijsberts and Sheepers, 2002; Norris and Inglehart, 2019; Oesch, 2008). Moreover, the statistical significance of the political assessment for non-voters reveals that dissatisfaction with the political system tends to boost abstention (H2B confirmed).

As expected, populist attitudes present a positive coefficient and are statistically significant for populist voters, which means that populism increases in a 2.9% the likelihood of voting for Chega (H3A confirmed). This finding is in line with previous studies exploring the link between populist attitudes and populist voting in Portugal (Heyne and Manucci, 2021). However, contrary to our expectation, the populist score also presents a significant impact on non-voters, but in this case, the effect is much weaker (significant at 0.05 level). The AME analysis also gives us an idea of the difference in the magnitude of the effect: a one-point increase in the populism scale enlarges the probability of abstaining by 1.2% and the probability of voting for the populist radical right by 2.9%. In our opinion, this can be interpreted as a partial overlap between populist voting and abstention. In other words, populist attitudes may have an ambivalent effect, sometimes favouring abstention (rather than voting for non-populist parties) and sometimes supporting PRRP. From this viewpoint, contingent factors may be key to explaining the final impact of populist attitudes in favour (or against) electoral participation.

Our findings also confirm our expectations regarding the impact of attitudes towards unconventional participation on populist voting (H4A confirmed). The positive and statistically significant coefficient means that, in Portugal, populist voters are distinct from non-populist voters and abstainers because they give more value to street demonstrations than to institutional politics. This result is in line with previous studies exploring the relationship between populism and non-institutional political participation (e. g. Pirro and Portos, 2020). However, the results do not confirm our hypothesis related to electoral participation, as the impact of protest-related preferences does not achieve standard levels of statistical significance.

Social integration is positively associated with abstention, which means that individual trust in other people does not foster higher levels of mobilisation, but the coefficient fails to achieve conventional standards of statistical significance (H5B not confirmed). On the other hand, social trust does not have a relevant impact in explaining PRRP support, as there is no difference between voters of Chega and voters of non-populist parties (H5a not confirmed).

As for programmatic preferences, our findings shed light on a noteworthy association between electoral participation and anti-immigration attitudes. Specifically, individuals with stronger anti-immigration preferences are significantly more inclined to abstain when compared to those who hold more positive views on immigration. Furthermore, group attitudes linked to citizens’ preferences emerge as robust determinants of populist voting in Portugal. This result substantiates hypothesis H6, underscoring how exclusivist attitudes toward migrants clearly differentiate populist right-wing voters from those who align with non-populist parties.

Lastly, attitudes concerning the European integration process also wield a substantial influence over both groups of voters (H7). On the one hand, abstentionists emerge as distinct from the traditionally Euroenthusiastic majority, underscoring their divergence from prevailing pro-European sentiments. On the other hand, the emerging populist radical right party appears to successfully mobilise voters who harbour more negative attitudes toward the European integration process. This multifaceted interplay of programmatic preferences adds depth to our understanding of populist voting dynamics in Portugal.

Concluding remarks

There is an ever-growing number of empirical studies analysing various aspects of populism. One of the main strands of research has focused on the electoral basis of populist support. Despite the increasing knowledge on this topic, we still know very little regarding the similarities between populist voters and abstentionists. This is of the utmost importance not only for normative reasons, such as understanding to what extent populist support may influence voter turnout but also from an empirical standpoint. It remains unclear what the rationales and mechanisms are behind these two forms of collective action.

We conducted a cross-sectional survey and utilised original data to statistically evaluate the key characteristics of non-voters and supporters of the populist radical right in Portugal. While our estimations do not provide conclusive evidence of causal relationships, the findings presented in this paper shed light on the extent to which these two phenomena share similar correlates. Our results suggest that populist support and abstention are driven by partially distinct logic. Non-voters appear to exhibit signs of apathy, maintaining a considerable distance from the political system. This “exit” behaviour is reflected in their low levels of political interest and income, setting them apart from PRRP supporters. However, both groups display heightened sensitivity to specific political issues, such as dissatisfaction with the democratic system, anti-immigration sentiments, and Euroscepticism. This implies that the protest element (“voice,” in Hirshman’s terms) is present in both non-voters and Chega supporters. This overlapping characteristic offers an insight into the electoral success of Chega in the 2022 and, especially, in the 2024 legislative elections. While abstention may encompass “marginal” or “peripheral” voters, i. e., individuals less integrated into the political system, the distinction between populist and non-populist voting appears to be more related to short-term variables and programmatic orientations than socio-structural determinants.

The first important implication of this research is that populist voters are a relatively unstable electorate, whose support depends not only on orientations towards specific issues but also on the party supply. Therefore, the secret of populist success lies in the match between the demand and supply side. Overall, our findings speak also to the strand of research that investigates the relationship (at the aggregate level) between turnout and populist party success. From this viewpoint, the results of this study seem to confirm the capacity of PRRP to mobilise “strategic abstentionists”. While the “protest” component of populist support has, to a certain extent, absorbed the abstention associated with short-term issues, it appears to be a contextual phenomenon subject to short-term fluctuations.

This compels us to discuss a significant implication of this study, namely the impact of populist parties on the turnout trend. Can they reverse the declining voter participation observed in many European democracies over recent decades? Answering this question is complex because extrapolating trends from individual-level data to the aggregate level can be challenging. We also recognise that electoral participation can be influenced by strategic factors, including party competition dynamics, leadership, and the broader political system. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that PRRP may have the potential to mitigate the decline in turnout when they successfully appeal to “strategic” abstentionists. Conversely, mobilising more apathetic voter groups, especially those less integrated into the political system, appears to be a more formidable challenge. This implies that the potential decrease in turnout is primarily influenced by the political supply, which depends not only on populist rhetoric but also on the performance of established parties. In the long term, voters may also respond to populist discourse with a sense of fatigue, driven by the negative impact of hate speech and the coarsening of political discourse, which could lead them to disengage from politics.

While this paper has explored various commonalities between abstentionists and voters of populist parties, it presents several shortcomings. Firstly, the challenge of interpreting these findings may be attributed to methodological considerations, in particular the fact that we aggregate very different types of parties within the “non-populist” category. Secondly, relevant variables, such as leader evaluation, might have been omitted from the analysis. Existing research has underscored the significance of leader evaluation, not only in mobilising the electorate but also in bolstering support for populist parties (Blais and St-Vincent, 2011). Unfortunately, however, this component was not available for the Portuguese case, making it impossible to test its impact. Future investigation might well focus on including leader evaluation to explain the specificities of populist support vis-à-vis abstention.