Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.96 Lisboa jun. 2013

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Strong ties inside and outside the neighbourhood. An exploratory analysis of the spatial dimension of ego/alter relations in three urban settings in Vienna

Laços sociais fortes dentro e fora do bairro. Uma análise exploratória da dimensão espacial das relações ego/alter em três áreas residenciais de Viena

Josef Kohlbacher1; Ursula Reeger2; Philipp Schnell3

1Senior researcher at and Deputy Director of the Institute for Urban and Regional Research, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna. E-mail: josef.kohlbacher@oeaw.ac.at

2Senior researcher at the Institute for Urban and Regional Research, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna. E-mail: ursula.reeger@oeaw.ac.at

3Researcher at the Institute for Urban and Regional Research, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna. E-mail:philipp.schnell@oeaw.ac.at

ABSTRACT

Regarding the spatial dimension of ego/alter relations, the fact whether egos and alters live within the same neighbourhood and the consequences thereof are heavily debated. Some authors argue that a network consisting mostly of people who live in the same urban area may result in lower socio-economic opportunities. Another strand of research emphasizes the importance of strong ties on the local level for neighbourhood embeddedness and social cohesion. In this article the role of the neighbourhood (a) in the formation of strong ties, (b) as the place where strong ties currently live and (c) as a meeting place for people sharing strong ties is investigated for three neighbourhoods in Vienna. In line with previous research results, it turns out that in the socially marginalized remote setting, strong ties are more often neighbourhood-based and less often interethnic. In the more affluent neighbourhood, strong ties are not so strongly bound to the neighbourhood, but are more spatially dispersed.

Keywords: Neighbourhood, strong ties, interethnic relations.

RESUMO

Laços sociais fortes dentro e fora do bairro. Uma análise exploratória da dimensão espacial das relações ego/alter em três áreas residenciais de Viena. Tem-se debatido muito até que ponto a dimensão espacial das relações alter-ego é ou não afectada pelo facto de o alter e o ego residirem no mesmo bairro. Alguns autores argumentam que uma rede social constituída sobretudo por pessoas que vivem na mesma área da cidade pode resultar em menores oportunidades socioeconómicas. Outra corrente de investigação enfatiza a importância de laços sociais fortes, ao nível local, para a coesão social e uma maior identificação da população com o lugar de residência. Neste artigo analisa-se o papel do bairro (a) na formação de laços sociais fortes, (b) como lugar de residência dos elementos que compõem a rede social mais íntima e (c) como lugar de encontro de pessoas que partilham laços sociais fortes, em três bairros da cidade de Viena (Áustria). Em consonância com resultados de pesquisas anteriores, verifica-se que nos bairros mais marginalizados socialmente, são mais frequentes as redes sociais confinadas ao bairro e com menos relações interétnicas. Nos bairros mais ricos, as redes sociais mais íntimas estão menos limitadas ao bairro e são espacialmente mais dispersas.

Palavras-chave: Bairro, laços sociais fortes, relações interétnicas.

RÉSUMÉ

Liens étroits inter et intra-quartiers. Dimension spatiale des relations ego/alter de trois quartiers de Vienne. La question a été posée de savoir jusquà quel point la dimension spatiale des relations alter/ego est affectée du fait de la cohabitation en un même quartier. Certains auteurs soutiennent quun réseau social constitué de gens habitant le même quartier urbain, pourrait conduire à une diminution des ouvertures socio-économiques. Dautres auteurs insistent sur limportance locale de forts liens sociaux pour favoriser la cohésion de la population et son identification avec son lieu de résidence. Dans cet article, on analyse le rôle de trois quartiers de Vienne (a) sur la formation de forts liens sociaux, (b) sur la localisation de ces liens dans le quartier, (c) sur le quartier comme lieu de rencontre des personnes qui partagent ces liens sociaux. A la suite de travaux antérieurs, il se confirmerait que cest dans les quartiers marginalisés du point de vue social que les relations inter-ethniques sont moins fortes et que cest dans les quartiers plus riches que les réseaux sociaux sont plus dispersés et non confinés au lieu de résidence.

Mots-clés: Quartier, liens sociaux étroits, relations inter-ethniques.

I. THEORETICAL INTRODUCTION

Though the question about the relevance of the local level in globalised urban environments is highly contested, international research has been able to prove that urban neighbourhoods are still of a great and even increasing importance as arenas of daily social interactions and coexistence (Ellen and Turner, 1997; Bridge, 2002; Forrest and Kearns, 2001; Lupton, 2003; Sampson et al., 2002). Neighbourhoods matter, not only as spaces, but as places of belonging and of feeling embedded. We have witnessed a certain renaissance of the notion of the neighbourhood among both policy makers and academics (Atkinson and Kintrea, 2001; Bauder, 2002; Buck, 2001; Clark and Drinkwater, 2002; Dietz, 2002; Ellen and Turner, 2003; Galster, 2007). Current research results also prove that the neighbourhood as a place of social interactions has a different meaning for different people (Guest and Wierzbicki, 1999). Economically active persons who spend less time at home may see the local level from a different point of view than the unemployed youth lacking financial resources or elderly people who are less mobile and thus more dependent on local ties (Turley, 2003; Müller, 2011). It must not be neglected that there are also counter perspectives which are critical towards the integrative power of diverse urban neighbourhoods (Amin, 2002). Wellman argued that The metropolitan area bounds the field of interaction more than does the neighbourhood (Wellman, 1979: 1211).

The neighbourhood is also one of the core arenas in which different types of ties develop (Hampton, 2007). These modes of social interactions can be characterized by different degrees of intimacy and are labelled as strong ties when the degree of intimacy is high, and weak ties with a lower degree of intimacy, such as loose acquaintances (e.g. chats with people in the neighbourhood; for details see Granovetter, 1973). It is an old question in empirical research at what point an acquaintance becomes a friend (Argyle and Henderson, 1985; Allan, 1989) and is to be under-stood as friendship (Kurth, 1970) from a social-psychological point of view. Clearly, close social relations such as friendships and friendly relations are usually characterized by some degree of interdependence (Kelly and Thibaut, 1978), though such close relations are always multidimensional (La Gaipa, 1977) and include sociological and psychological components (Lazarsfeld and Merton, 1954). It is also a fact that friends are not chosen by mere accident (Verbrugge, 1977), and that individual-oriented analyses must take into account the importance of similarity (Zeggelink, 1995). Furthermore close social interactions are not stable and static but in a permanent process of change. They may become closer or more distant depending on different events or stages in life, etc.

What are general causal factors of the choice of contact partners? One argument based on the concept of preference is that people build up their social circle by choosing acquaintances, friends and partners who are similar to them. The most plausible principles for meeting are status-homogeneity and spatial proximity. Strangers with similar social roles and beliefs are more likely to be in the same place at the same time, than those with different roles and beliefs. Also people whose daily rounds intersect are more likely to become acquaintances than others (Verbrugge, 1977: 577). The principle of homophily or preference for interaction with similar others guides social networks of every type, e.g. in social status or ethnic origin (Verbrugge, 1977; McPherson et al., 2001; Ganter, 2003: 68 ff.; Martinovic et al., 2009). In a series of psychological experiments, Byrne (1971) demonstrated that cultural similarity is indeed a favourable condition for the development of personal attraction. Another preference argument is that people favour interacting with others who are also socio-economically attractive (Kalmijn, 1998). European cities are attractive to immigrants from all over the world and thus becoming more and more diverse, therefore neighbourhoods are the places where people of different origin live together and probably get to know each other (Lancee and Dronkers, 2011; Tolsma et al., 2009; Müller and Smets, 2009; Schlüter, 2011). Thus, the study of interethnic contact is important, because such contact has implications for the structural and cultural integration of immigrants (Lancee and Dronkers, 2011; Boschman, 2012). Interaction between ethnic groups can be especially beneficial for the migrants in that they can gather new information, gain access more easily to the local labour market, and become familiarised with the social norms and the culture of the country of residence (Müller and Smets, 2009). A profound understanding of interethnic contacts on the local level is, thus, important because increasing social interaction may also speed up the cultural and economic incorporation of migrant population (Hagendoorn et al., 2003), thereby ensuring a more cohesive society. A number of perspectives have been used to investigate interethnic relations. They range from large samples and official statistics (Ganter, 2003; Haug, 2010), to countries (Tolsma et al., 2009; Boschman, 2012) but also certain cities and areas (Wellman, 1979; Pinkster and Völker, 2009; Müller and Smets, 2009; Müller, 2011). Smets and Kreuk (2008) for example show that the interethnic contacts between native Dutch and Turks are more dynamic and diverse than often assumed in the integration debate. Moreover, the interethnic contact between native and Turkish neighbourhood residents demonstrates that there is not one single pattern; different types of interethnic contact can be distinguished within and between both ethnic groups. Similar but also diverging results for interethnic contacts and network formation in a deprived neighbourhood in the German city of Cologne were found by Blasius et al. (2008).

According to the classical analysis by Granovetter (1973), most people have only a small set of strong ties, which are non-clustered. Social network analysis provided evidence that most people have more friends outside of their neighbourhood than within it (Wellman, 1979) and that neighbourhood ties have become less prevalent (Guest and Wierzbicki, 1999). Regarding the nexus between the location of strong ties and the social class dimension (on the individual level and on the level of neighbourhoods), there is empirical evidence from previous research that ties beyond the neighbourhood are increasing and becoming dissociated from forms of local interaction (Guest and Wierzbicki, 1999), with elderly and inactive people depending more on local ties while mass populations develop more spatially diffuse networks. In the case of two Dutch neighbourhoods, Pinkster and Völker (2009) found out that residents in a low-income neighbourhood do not differ from those in a mixed neighbourhood with regard to the degree to which they receive social support, though networks of low-income residents provided fewer resources in terms of prestige. According to Webber (1964), working class residents are less mobile, displaying more ties within the neighbourhood. Laumann (1973) reported results that point in the same direction, with a working class status being associated with denser, more spatially constrained social networks (Bridge, 2002: 10). The class dimension was also analysed by Henning and Lieberg (1996), who state that the nature and significance of networks is affected by social class, with the local arena being more important for blue collar workers, which is in line with the observation that neighbourhood relations might be relatively more significant for those with limited economic resources and mobility (Bridge, 2002: 12). Opposite results were provided by Guest and Wierzbicki (1999), who argue that there is an increasing dissociation between neighbourhood and extra-neighbourhood ties, with certain individuals becoming specialised in localised versus non-localised social interaction. However, they could not find strong evidence for certain socio-demographic sub-groups of the population (Bridge, 2002: 7). Not all ties are equal, and not all interactions have the same effects in all neighbourhoods. The study of neighbourhood effects has found that the formation of social ties and the influence of ties vary by neighbourhood characteristics, especially as they relate to socioeconomic status and residential stability (Sampson et al., 2002). An individual in an area of high residential mobility faces quite different constraints than residents of stable areas (Sampson, 1988: 768), as community-level instability constrains friendship choices and reduces local ties. As an example, residential stability and the presence of social ties in affluent neighbourhoods are protective of mental health (Ross and Jang, 2000).

The majority of most peoples social support is not an outcome of social ties in the neighbourhood, but this does not automatically mean that local ties are unimportant. Social network analysis has proved that neighbourhood ties are the source of some specific types of support, such as the provision of certain everyday services, such as child-care or emergency aid (Wellman and Wortley, 1990). Large local friendship networks are associated with greater empowerment (Geis and Ross, 1998), less mistrust (Ross and Jang, 2000), and lower levels of mental distress (Ross, 2000; Elliott, 2000).

As to the spatial dimension of strong ties, from the individual point of view the fact whether close contacts live within or outside the neighbourhood and the consequences thereof are heavily debated. Some authors argue that a network consisting mostly of people who live in the same urban area results in an insular community distance from what is going on out there or in other words from mainstream society and may e.g. result in lower socio-economic opportunities. It must also be emphasized that strong ties do not automatically produce informal neighbourhood social controls (Shafer et al., 2006). Another strand of research emphasizes the importance of strong ties on the local level for neighbourhood embeddedness and social cohesion, a fact that has also been proved by analysing the GEITONIES datai for the neighbourhoods in Vienna (Kohlbacher et al., 2012). According to this analysis, having close friends or relatives living nearby is highly associated with the degree of neighbourhood embeddedness, irrespective of the neighbourhood type (e.g. affluent or deprived) and applies to both migrant and native respondentsii. This result led to the decision to take a closer look at the spatial dimension of strong ties and carry out the following in-depth analysis, which deals with the role of different types of neighbourhoods:

(a) in the formation of strong ties (as the place where the first encounter took place),

(b) as the place where strong ties currently live and

(c) as a meeting place for people sharing strong ties.

An innovative aspect of the present approach is the shift from the respondents to their alters in so-called ego-centred networks. In this approach the respondents represent the egos, while the persons they have named in the survey as their most important strong ties are defined as their alters. We will not look at the egos, but at their alters, and analyse them: Where do the alters live, where did they meet the ego and where do they usually meet the ego nowadays? For this purpose we have derived a database from the original GEITONIES dataset (see more detailed description below) that includes all close contacts and the information gathered for each of them in separate small questionnaires as single cases (all data on friends and/or relatives from the original data set reversed). This changes the perspective from the respondents to their close contacts (from the ego to his/her alters).

On the general level, we will differentiate between strong ties of migrants and natives, as we are interested in the variations in the role of the neighbourhood for strong ties between these two groups. For each of these two groups we will further-more make a distinction between relatives and friends, because e. g. the mechanisms of encounter are completely divergent between these different types of strong ties. Previous research also proves other substantial differences between strong ties who are relatives and those who are friends. McPherson et al. (2001: 431) point out that family ties have a somewhat different structure than the more voluntary, less intense social ties of co-employment, co-membership, or friendship....

As we are interested in the differences in the spatial dimension of ego/alter relations between different types of neighbourhoods, we will present the results for three spatial entities in Vienna, that differ in terms of socio-economic structure, built environment and location in the city. The following chapter provides general characteristics of these three urban settings.

II. THE NEIGHBOURHOODS

In the project GEITONIES, the neighbourhoods were selected based on a common set of criteria, such as the size of the residential population (between 3,000 and 10,000 inhabitants), differences in ethnic concentration levels and a clear structure without internal barriers, breaks or other major non-residential areas. Thus, the selected neighbourhoods represent compact and homogeneous living areas and can be seen as specific neighbourhood types for the city instead of the broad and often used census tracks. As to the choice of the neighbourhoods, it was furthermore of utmost importance not to include special cases (e.g. urban settings that receive much attention in the media or in public discussion) but to find neighbourhoods that repre-sent typical examples of the situation in Vienna with regard to the physical structure of the built environment as well as structural characteristics of the population. Furthermore we aimed at including urban settings that differ in terms of the social status of the population.

Neighbourhood 1, Laudongasse in the 8th district, is an attractive inner city location with a medium to high socio-economic structure dominated by a 19th century housing stock (Founders period) that gained attractiveness during the 1990s as a housing area for the better-off. In 2010, the total population was about 3,930 persons, 31% of whom had a migration background (average share of persons with a migration background in Vienna: 33%). Generally speaking, the housing stock is in a good condition of repair with the rental segment clearly dominating (little social housing and below average owner-occupied housing). The population consists to a high proportion of young(er) urban professionals, which is mirrored in the high percentage of economically active residents (50.1%), clearly above the city average. The high proportions of university graduates and high-skilled employees (according to the Census 2001, both 23%) are an explanation for the low rate of unemployment in this neighbourhood. Low-skilled workers constitute a small minority there. Residents can find all necessary facilities just around the corner, be they schools, shops, restaurants, doctors etc., as well as public transport.

The second urban setting almost entirely belongs to the social housing segment and lies in the outskirts of the city. For this reason it represents a perfect counterpart to the other two neighbourhoods. Am Schöpfwerk (12th district), as it is called, has about 2,100 flats and 5,900 residents and was built between 1976 and 1980 as a greenfield development (in the place of the former, rather rural, suburb Altmannsdorf). It is an example of the large communal blocks that were erected from the beginning of the 1960s onwards at the urban periphery to meet the general lack of housing in Vienna. Am Schöpfwerk, with its lower class-dominated population structure, a relatively high proportion of unemployed persons and social disintegration processes, provides an example of the problems found in parts of social housing in Vienna. As to the ethnic composition, it has to be pointed out that social housing in general was not accessible for foreign citizens before the 1st January 2006. The consequence is that foreign citizens formed a minority among the tenants of social housing. What happened in communal housing was an inflow of Austrian citizens with a migrant background after naturalization. Currently we are witnessing a catching-up process, the share of persons with a migration background reached 36% in 2010 (slightly above the city average). As the flats are relatively new, they are well equipped. Furthermore, residents can find basic infrastructure within this residential area (two schools, a kindergarten, a day-care for schoolchildren, clubs for different age groups, a library, a post office, a police station, a social services office, a housing advice centre, a number of different shops, a bank and some doctors offices). The neighbourhood is also well connected with Viennas public transport system.

The third neighbourhood, Ludo-Hartmann-Platz in the 16th district, is a typical working class area bordering the inner city with a high share of migrant population. Like in Laudongasse, most of the housing stock was built in the 19th century during the Founders period, though not for the bourgeoisie, but already back then for poor immigrants and labourers. The area is close to the Gürtel, a thoroughfare with three lanes of traffic in each direction and public transportation, which is extremely noisy and air-polluted. Many blocks of flats are in a bad state of repair, consisting of small, badly equipped housing units and therefore inhabited by a mixture of socially marginalized Austrians and immigrants. Nevertheless, the infra-structure is sufficient and the public transport situation is excellent. Among the 3,900 inhabitants, 63% have a migration background (almost twice the city average).

III. DATA AND STRUCTURE OF THE SAMPLE

The present exploratory analysis is based on the data from the three neighbourhoods in Vienna derived from the GEITONIES database. Within each selected neighbourhood, a stratified random sample was generated based on an inventory of all addresses, with the aim of including 100 migrants and 100 native born persons in the final sample. In the survey, these respondents were asked to name up to eight most important persons outside their household (e.g. family members, friends, colleagues, co-students, neighbours or other acquaintances) irrespective of where these persons live, so respondents should take into consideration all their close relationships. At most two persons could be named for each of the four contact fields spending free time (mutual visits, going out, sporting, vacations), confidentiality and advice (in case of changes in the personal life or in the family, in need of a decision), helping out (in a substantive way like taking care of the house, children or parents, lending money, help in finding a good doctor or education) and other relationships, with the possibility to name the same person in more than one contact field. For each of the close contacts, be they friends or relatives, a set of information was gathered separately in the survey, including basic demography and in-depth data regarding the beginning of the relationship, such as the exact place of encounter, the occasion, why people met, as well as the current state of the relationship in terms of the current place of living of the strong ties as well as the means and places of meeting. The following analysis is based on these data on strong ties.

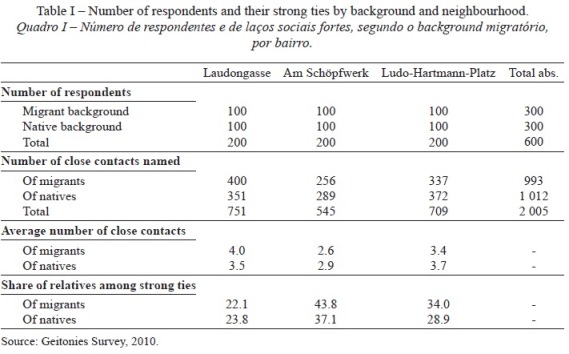

Table I provides some basic information on the dataset: The number of respondents by definition was always 100 migrants and 100 natives in each of the neighbourhoods. Different numbers of strong ties were named by them, e.g. the 100 migrant respondents in Laudongasse named 400 strong ties, 100 natives in Am Schöpfwerk named 289 strong ties. In total, data on 2,005 strong ties of migrant and native respondents enter the analysis. The average number of strong ties is highest among migrant respondents in the better-off inner city neighbourhood Laudongasse (4.0), migrants in the social housing estate Am Schöpfwerk in the outskirts of the city on average named the lowest number of strong ties (2.6). Natives in the rather deprived area around Ludo-Hartmann-Platz on average have most strong ties compared to the natives in the other two settings.

In the introduction we stated that we will differentiate between strong ties who are relatives (and who were met under completely different circumstances than friends, mostly either at the birth of the ego or at the birth of the alter) and those who are friends and have thus been met at some point in time (at school, at work, while spending free time, in the neighbourhood etc.). Table I displays the share of alters who are relatives for both migrants and native respondents in the three urban settings and it reveals the respective communalities and differences. Other possible reasons for knowing each other include the field of study and work (as colleagues, fellow students) and the field of free time (e.g. in organisations or clubs). These other fields of encounter are not included in the table and will only be discussed in the following if relevant.

Generally speaking, the most important reasons why people got to know each other, differ between the neighbourhoods but not so much within them (between the strong ties of migrant and native respondents). In the more affluent inner city setting (Laudongasse) it is the spheres of school/university and work, where most strong ties can be found. Relatives as well as other contexts like organisations and clubs are of minor importance in this urban setting. The social housing area Am Schöpfwerk shows a different pattern: Relatives represent the most important group of strong ties, both among native and migrant respondents, 43.8% of the migrants strong ties are family members, among the natives alters the share amounts to 37.1%. Concering migrants alters in the deprived area bordering the inner city (Ludo-Hartmann-Platz), it is both relatives (34.0%) and the sphere of work/school (29%) where most strong ties are established. Natives in this neighbourhood found most of their strong ties at work/school, or again within their own family (28.9%).

Table I points out the importance of relatives as strong ties. We therefore will split the respondents strong ties into two separate groups, namely relatives and friends in some of the upcoming steps in which we will concentrate on the role of different types of neighbourhoods in the formation and current state of close relations.

IV. A CLOSE LOOK AT STRONG TIES 1. Where it all began: the place of getting to know each other

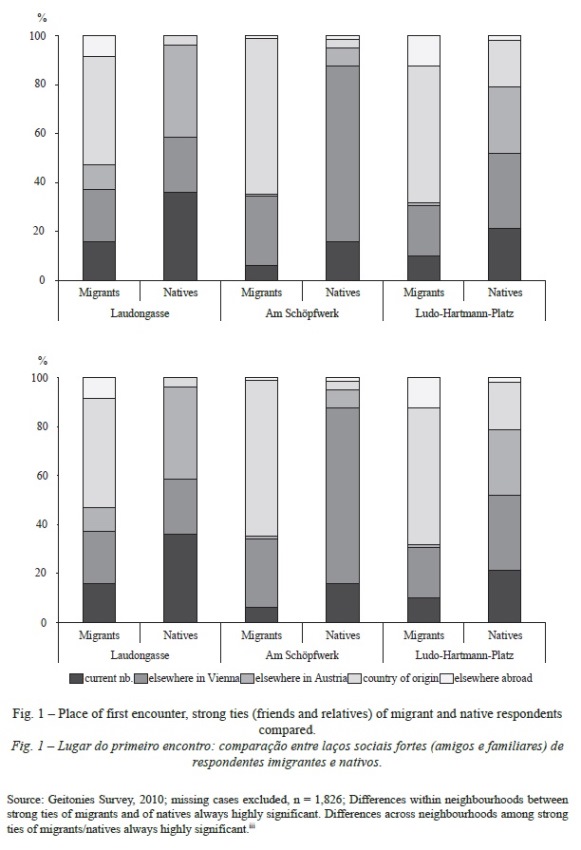

The first analytical step refers to the exact place where people got to know each other. Did the respondents and the alters (friends and relatives) meet in the current neighbourhood, elsewhere in Vienna, elsewhere in Austria, the country of origin (mostly relevant for alters of migrants) or somewhere else abroad? What is the role of the local level as the place of first encounter? This step leads away from the con-text of the encounter and only refers to the spatial dimension of getting to know each other.

The first central message from figure 1 is that there are pronounced differences between relatives and friends of both migrant and native respondents regarding the places of first encounter. For friends, the category elsewhere in Vienna is of utmost relevance (for all sub-groups more than 50% except for friends of native respondents in Am Schöpfwerk with 49.8%) irrespective of the background of the ego, which means that migrants have also met most of their friends in Vienna and not abroad. For relatives, the background of the ego clearly shapes the places of first encounter: relatives of migrant respondents have mostly been met in the country of origin (Laudongasse: 44.3%, Am Schöpfwerk: 63.7%, Ludo-Hartmann-Platz: 56.1%), for example at the birth of the alter or the ego. On the other hand, relatives of native respondents show diverging patterns with the local level (35.8%) and the rest of Austria (37.7%) being relevant in affluent Laudongasse, the rest of Vienna being important in Am Schöpfwerk (71.6%) and no clear direction in Ludo-Hartmann-Platz.

Interestingly, most of the friends of migrants were first met in Vienna, which means that friendship ties with the country of origin are more or less not kept (anymore). One reason is that Vienna has a long migration history and therefore there are quite a lot of second generation migrants who were socialized in Vienna, went to school and made friends here. But also many of the first generation migrants have been in Vienna for decades, which results in diminishing friendship relations with people in the country of origin and many friends that have been met in Vienna. On the other hand, migrants might also have made friends with co-ethnics who also came to Vienna at some point in time. The question of interethnic and co-ethnic relations will be clarified in the last sub-chapter of this section. Focusing on the neighbourhood as the place of first encounter, it is of some relevance for friends, mostly in the social housing area Am Schöpfwerk, where 29.2% of migrants friends and 37.8% of natives friends were first met. But also in the two other settings, some friends were met on the local level of the current neighbourhood, e.g. every fourth strong tie of migrant respondents in Ludo-Hartmann-Platz. For relatives, the pattern differs between migrants and natives, with the latter displaying higher shares in all three neighbourhoods.

2. The current situation: place of residence of strong ties

Where do the strong ties of migrant and native respondents currently live? Is the neighbourhood relevant as a place of living together or do the strong ties live somewhere else? What about the differences between the neighbourhoods – is the local arena more important in the deprived areas in terms of strong ties living nearby?

The first observation clearly is that elsewhere in Vienna dominates in almost all subgroups as the current place of living of the strong ties, e.g. 65.0% of the natives friends in the deprived area around Ludo-Hartmann-Platz live in another part of Vienna. In the subgroup of friends, the proportion of those who live in the same neighbourhood as the related respondent is considerable in the socially marginalized housing estate Am Schöpfwerk at the outskirts of the city, among both friends of migrants (32.9%) and of natives (30.3%). In the two other neighbourhoods, the respective shares are lower. Again it is interesting to note that most of the migrants friends live in Vienna, while the country of origin plays a minor role (e.g. 6.6% of migrants friends in Ludo-Hartmann-Platz live in the country of origin). These shares are considerably higher among migrants relatives (Laudongasse: 19.5%, Am Schöpfwerk: 11.9%, Ludo-Hartmann-Platz: 18.3%). But after all it is not surprising, as migrants friends have mostly also been encountered in Vienna and not abroad (fig. 2).

Generally speaking these results are in line with Henning and Lieberg (1996), who performed similar research in different neighbourhoods of Linkoping in Sweden and also investigated strong and weak ties. They found the neighbourhood to be rather unimportant; for both white collar and blue collar residents, 75% of contacts happened outside the neighbourhood.

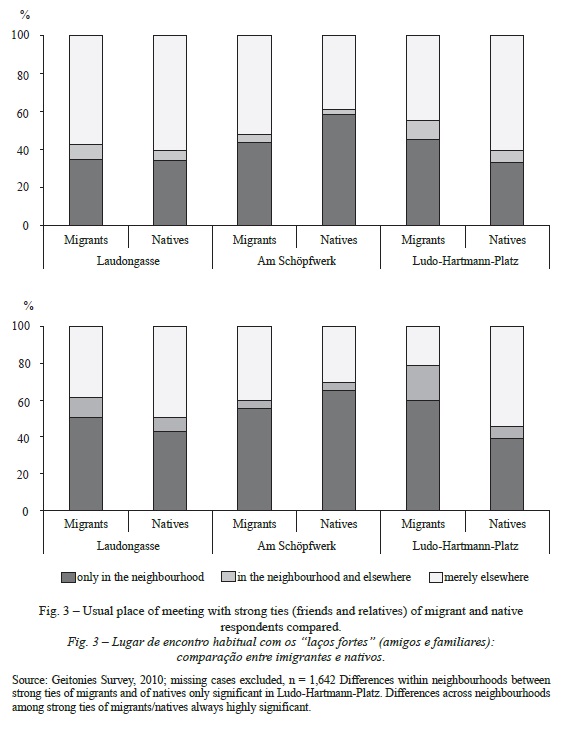

3. The neighbourhood as a meeting place

So far, we have looked at the neighbourhood in comparison to other locations where people first met and where they are currently living. In a third step we will look at the places where people usually meet nowadays. Is the neighbourhood important as the place where people get together? What are the differences between the neighbourhoods in this respect?

Compared to the role of the neighbourhood as a place of encounter or as the place where strong ties live, it is obviously of much more relevance as the place where people usually meet (fig. 3). Furthermore, the neighbourhood is more significant for relatives than for friends in this respect. With friends, people tend to go out to restaurants, bars or to cultural events, while meetings with relatives are more likely to happen in the private sphere of the home. Both types of strong ties of natives in Am Schöpfwerk display the highest shares of neighbourhood based get-togethers, with 65.2% of relatives and 58.5% of friends only being met in the respective neighbourhood. In the attractive inner city neighbourhood Laudongasse get-togethers with friends in the neighbourhood happen significantly less frequently, both among strong ties of migrants and of natives. Meetings with relatives are also often neighbourhood-based, just like in the two other urban settings, with the only exception being relatives of natives in Ludo-Hartmann-Platz, who are more often met only outside the neighbourhood, which is possibly related to the central location of this neighbourhood combined with the sometimes poor housing situation.

4. Interethnic friends and the neighbourhood

The final question is the role of the neighbourhood in interethnic strong ties. In this step relatives are excluded from the analysis as they are by nature almost entirely co-ethnics (except for the case of interethnic marriage, but the numbers are very small)iv. The present data allow for a differentiation between co-ethnic (same origin) and interethnic (other origin) close friends. Again we will look at the neighbourhood as a place of encounter, the place where strong ties live and/or meet the egos and the analysis is provided for friends of migrants and natives separately.

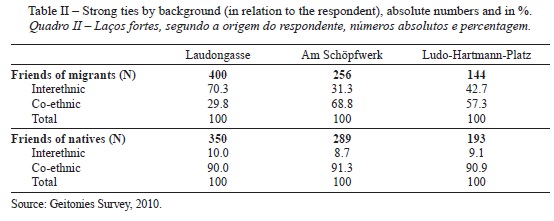

To start with a general description of the extent of interethnic/co-ethnic relations in the whole sample and the three neighbourhoods separately, the close friends of Austrians are to a large extent also Austrians with 90.7% of their alters being co-ethnics of the respective respondents. This result is surprising, given the long migration history of Vienna and the high share of migrant population (33%), which is not reflected in the strong friendship ties of natives. The picture changes when we turn to the friends of migrants, of whom 50.9% are not co-ethnics but come from a different country than the respondent or from Austria (table II).

Disaggregating these general results by neighbourhoods reveals enormous differences among migrants friends: in Laudongasse, 70.3% of them are interethnic, followed by Ludo-Hartmann-Platz with 42.7% and the lowest share of interethnic close relations of migrant respondents is observed in the marginalized social housing area Am Schöpfwerk (31.3%), where the clear majority of migrants alters are co-ethnics, a sign of delayed social integration. In the case of friends of native respondents, it is astonishing that there are more or less no differences between the three neighbourhoods: only about 9% of the alters are interethnic and thus the majority are Austrian alters, just like in the sample as a whole.

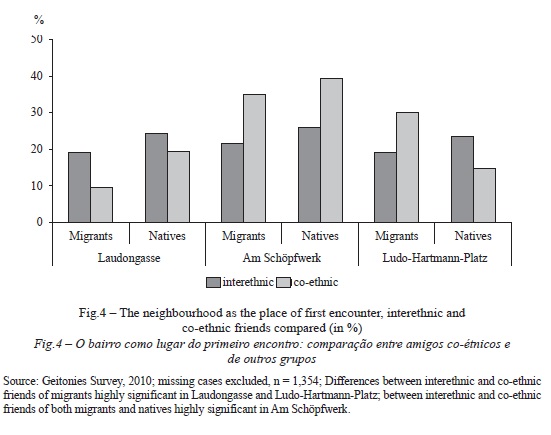

Looking at figure 4 v, the distinct migration situation in each neighbourhood has to be kept in mind with regard to encountering non-co-ethnics on the local level in terms of opportunity structures. To begin with the affluent inner city environment around Laudongasse, migrants as well as natives are more likely to have met their interethnic friends in the current neighbourhood than their co-ethnic friends. In Am Schöpfwerk, almost 40% of the Austrian alters of Austrian respondents were met in the neighbourhood, which is partially due to the fact that in this greenfield development all inhabitants moved in more or less at the same time and at the same age, which made connecting easier. At the same time it is also Am Schöpfwerk where migrants got to know most of their co-ethnic friends. In the working class neighbourhood bordering the inner city, Ludo-Hartmann-Platz, every third co-ethnic alter of a migrant respondent has been encountered on the local level, whereas interethnic contacts came into existence considerably less often. Among the friends of natives, this pattern is reversed with more interethnic friends having been met in the current neighbourhood than co-ethnic ones.

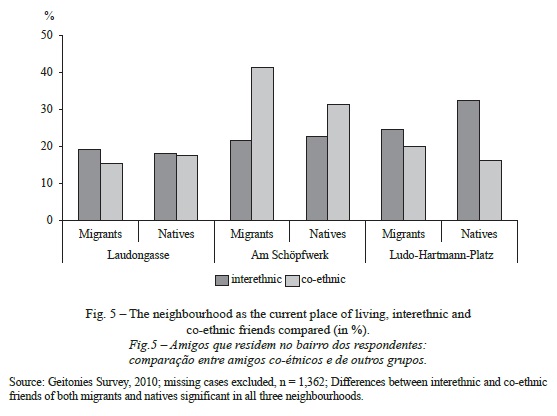

There are two observations in figure 5 that strike the eye immediately: first, the high share of co-ethnic friends of migrants who are currently living in the same neighbourhood (41.3%) in the marginalized setting Am Schöpfwerk, and at the same time the high share of Austrian friends of natives (31.4%) who are also living in the same urban area. So in this remote, socially marginalized area, both migrants and natives tend to stick to co-ethnic friends (fig. 4 and table II), which can be problematic in terms of socio-economic opportunities. Secondly, every third inter-ethnic alter (32.4%) of natives in Ludo-Hartmann-Platz is also residing there, which means that this area with its high share of migrant population provides the opportunity for interethnic friendship. For the affluent area around Laudongasse, the neighbourhood as the place where interethnic and/or co-ethnic friends live is of minor importance, they live more or less spread across Vienna.

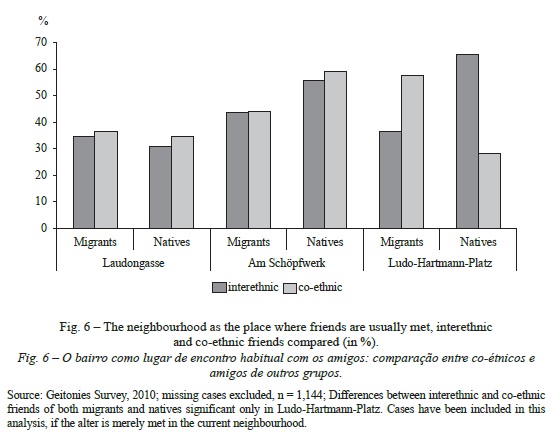

Concerning the role of the neighbourhood as the usual meeting place, the two neighbourhoods Laudongasse and Am Schöpfwerk display more or less no differences between interethnic and co-ethnic alters. In the marginalized social housing area, natives meet more than 55% of both interethnic and co-ethnic friends at home or somewhere else in the neighbourhood, while among friends of migrants the respective shares are a little lower. In the area bordering the inner city, marked differences between friends of migrants and those of natives occur: more than 65% of the interethnic friends of natives are met in the current neighbourhood, meetings with co-ethnics more often happen outside the neighbourhood. On the other hand, migrants meet 57.7% of their co-ethnic alters within the local setting, interethnic friends are met somewhere else (fig. 6).

V. CONCLUSION

The present exploratory analysis deals with the spatial dimension of socially intimate ego/alter relations in three different neighbourhoods in Vienna. The core questions that were at the focus of the exploration included the role of different types of neighbourhoods in the formation of strong ties, as the place where strong ties currently co-exist and as the meeting places for alters with their egos. We elaborated these questions for alters who are friends and those who are relatives separately and we also took a closer look at the importance of the neighbourhood as the place for inter and co-ethnic relations.

Generally speaking, the differences between strong ties of migrants and those of natives are often pronounced between the three neighbourhoods but not so often within them, which points to the significance of the local level and its characteristics.

This means that neighbourhood matters (Ellen and Turner, 1997, 2003) and its outcome can, of course, be measured (Lupton, 2003). It matters in terms of inter-ethnic contact (Müller and Smets, 2009; Müller, 2011) and of socio-economic status, for shaping close social interactions and thus supporting the social cohesion (compare Forrest and Kearns, 2001) of both migrant and native respondents. An observation which does not neutralize the relevance of the local context is that for some dimensions that have been analysed, the city seems to be more important than the neighbourhood, e.g. as the place where people first met their friends (but not their relatives) and as the place where close friends and also relatives currently live. This can be explained on the one hand by relatively high frequencies of moving and on the other by the fact that the first encounter with friends often happens at the work place, school, university or during outdoor leisure activities – places of interaction, which are very often located outside the neighbourhood of residence.

Starting with the more attractive, affluent, inner-city location Laudongasse, 35.8% of natives met their relatives in the neighbourhood and 20% of native respon-dents close friends were met in the present setting. This points into the direction of some immobility with people staying in the neighbourhood where, e.g., their parents/children live(d). Anyway, the role of the local level as the place of coexistence of friends/relatives and their egos is of minor importance here, compared to the two other neighbourhoods. In Laudongasse meetings between alters and egos happen less frequently than in the other neighbourhoods. This proves that people with better economic resources have a wider set of opportunities for meetings outside the local context than lower class members, a result which stands in accordance with other studies (Bridge, 2002; Sampson, 2002; Smets and Kreuk, 2008). With regard to interethnic and co-ethnic friends, Laudongasse is of some relevance for the development of interethnic relations for both migrants and natives, e.g. 25% of interethnic alters of Austrians were met there.

Am Schöpfwerk has already been described as a more remote, marginalized setting consisting entirely of social housing and from previous research (Atkinson and Kintrea, 2001; Blasius et al., 2008; Schlüter, 2011) one could expect that here the local level is more important as the inhabitants face limited economic resources and are thus less mobile. In addition, this area is located relatively far away from the city centre and from the architectural point constitutes a somewhat more enclosed area. And indeed, native respondents found about 37% of their close friends in the neighbourhood. Am Schöpfwerk is also relevant in terms of coexistence with friends, both migrants and natives had almost one third of alters living there. Natives tend to meet their alters in the neighbourhood (65.2% of the alters are only met in the neigh-bourhood). Both alters of migrants and natives are very often co-ethnics, close inter-ethnic relations are rarely be found, which is not astonishing, taking into account the higher levels of xenophobic attitudes among lower class people (Di Giusto and Jolly, 2009). Alters very often live in the same neighbourhood, e.g. 41% of co-ethnic alters of migrants also live in Am Schöpfwerk. To summarize, strong ties in this setting are more often neighbourhood-based and less often interethnic, which is typical for low-class areas in other European metropolises, too (Bauder, 2002; Boschman, 2012).

Ludo-Hartmann-Platz represents the classic deprived, inner-city, working-class environment. It has twice the citys average migrant density. As a place of first en-counter, the local level doesnt play an important role. The neighbourhood is rather more important as the place of meeting for migrants alters (60% only on the local level), friends are more often met somewhere else. An important result is that contrary to Am Schöpfwerk, Ludo-Hartmann-Platz is the place for interethnic relations, both as the place of coexistence with strong ties and as a place for meeting. The causal factors for this difference may be found in a diverging population structure and the very high concentration of migrants in this neighbourhood. Both neighbourhoods are lower class areas but in Am Schöpfwerk more economically and socially marginalized people are allocated. In Ludo-Hartmann-Platz, old age pensioners, blue-collar workers, students and migrants live next door to each other. Typical for the Viennese situation is that the Founders Period building stock traditionally plays an important integrative role (Kohlbacher and Reeger, 2006; Rehberger, 2009) and this stock is dominant there.

[ Links ]

Argyle M, Henderson M (1985) The anatomy of relationships. Penguin Books, London. [ Links ]

Amin A (2002) Ethnicity and the multicultural city: living with diversity. Environment and Planning A, 34(6): 959-980. [ Links ]

Atkinson R, Kintrea K (2001) Area effects: what do they mean for British housing and regeneration policy? European Journal of Housing Policy, 2(2): 147-166. [ Links ]

Bauder H (2002) Neighbourhood effects and cultural exclusion. Urban Studies, 39(1): 85-93. [ Links ]

Blasius J, Friedrichs J, Klöckner J (2008) Doppelt benachteiligt ? Leben in einem deutsch-türkis-chen Stadtteil. Wiesbaden. [ Links ]

Boschman S (2012) Residential segregation and interethnic contact in the Netherlands. Urban Studies, 49(2): 353-367. [ Links ]

Bridge G (2002) The neighbourhood and social networks. CNR Paper 4, Bristol. [ Links ]

Buck N (2001) Identifying neighbourhood effects on social exclusion. Urban Studies, 38: 2251-2275. [ Links ]

Byrne D (1971) The attraction paradigm. Academic Press, New York. [ Links ]

Clark K, Drinkwater S (2002) Enclaves, neighbourhood effects and employment outcomes: ethnic minorities in England and Wales. Journal of Population Economics, 15: 5-29. [ Links ]

Dietz R (2002) The estimation of neighborhood effects in the social sciences: an interdisciplinary approach. Social Science Research, 31: 539-575. [ Links ]

Ellen I, Turner M (2003) Do neighborhoods matter and why? In Goering J, Feins J (eds.) Choosing a better life? Evaluating the moving to opportunity experiment. Urban Institute Press, Washington: 313-338. [ Links ]

Ellen I, Turner M (1997) Does neighborhood matter? Assessing recent evidence. Housing Policy Debate, 8: 833-866. [ Links ]

Elliott M (2000) The stress process in neighborhood context. Health and Place, 6(4): 287-299. [ Links ]

Forrest R, Kearns A (2001) Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood. Urban Studies, 38(12): 2125-2143. [ Links ]

Galster G (2007) Should policymakers strive for neighborhood social mix? An analysis of the Western European evidence base. Housing Studies, 4: 523-546. [ Links ]

Ganter S (2003) Soziale netzwerke und interethnische distanz. Theoretische und empirische Analysen zum Verhältnis zwischen Deutschen und Ausländern. Wiesbaden. [ Links ]

Geis K J, Ross C E (1998) A new look at urban alienation: the effects of neighborhood disorder. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61(3): 232-246. [ Links ]

Granovetter M (1973) The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78: 1360-1380. [ Links ]

Guest A, Wierzbicki S (1999) Social ties at the neighborhood level: two decades of GSS evidence. Urban Affairs Review, 35: 92-111. [ Links ]

Hagendoorn L, Veenman J, Vollebergh W (2003) Integrating immigrants in the Netherlands: cultural versus socio-economic integration. Ashgate Publishing Limited, Aldershot. [ Links ]

Hampton K N (2007) Neighborhoods in the network society the e-neighbors study. Information, Communication & Society, 10(5): 714-748. [ Links ]

Haug S (2010) Interethnische kontakte, freundschaften, partnerschaften und ehen von migranten in deutschland. Working Paper 33 des Bunde samtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge, Series Integrationsreport, Part 7. Berlin. [ Links ]

Henning C, Lieberg M (1996) Strong ties or weak ties? Neighbourhood networks in a new perspective. Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 13: 3-26. [ Links ]

Kalmijn M (1998) Intermarriage and homogamy: causes, patterns, trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 24: 395-421. [ Links ]

Kelly H H, Thibaut J W (1978) Interpersonal relations: a theory of interdependence. Wiley, New York. [ Links ]

Kohlbacher J, Reeger U (2006) Die Dynamik ethnischer Wohnviertel in Wien. Eine sozialräumliche Longitudinalanalyse 1981 und 2005. ISR-Forschungsberichte, 33. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, Vienna. [ Links ]

Kohlbacher J, Reeger U, Schnell P (2012) Neighbourhood embeddedness and social coexistence. Immigrants and natives in three urban settings in Vienna. Isr-Foschungsberichte, 37. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, Vienna. [ Links ]

Kurth S B (1970) Friendships and friendly relations. In McCall G J, McCall M M, Denzin N K, Suttles G D, Kurth S B (eds.) Social relationships. Aldine, Chicago: 136-170. [ Links ]

La Gaipa J J (1977) Testing a multidimensional approach to friendship. In Duck S (ed.) Theory and practice in interpersonal attraction. Academic Press, London: 72-95. [ Links ]

Lancee B, Dronkers J (2011) Ethnic, religious and economic diversity in the neighbourhood: ex-plaining quality of contact with neighbours, trust in the neighbourhood and inter-ethnic trust for immigrant and native residents Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(4): 597-618. [ Links ]

Laumann E O (1973) Bonds of pluralism. Wiley, New York. [ Links ]

Lazarsfeld P F, Merton R K (1954) Friendship as social process: a substantive and methodological analysis. In Berger M (ed.) Freedom and control in modern society. D. van Nostrand Company, Toronto: 18-66. [ Links ]

Lupton R (2003) Neighbourhood Effects: can we measure them and does it matter? London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics, CASE paper 73, Sept. [ Links ]

Martinovic B, Tubergen van F, Maas I (2009) Dynamics of interethnic contact: a panel study of immigrants in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 25(3): 303-318. [ Links ]

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook J M (2001) Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27: 415-444. [ Links ]

Müller T (2011) Interethnic interactions and perceptions of immigrant men in public space: the experience of community safety by seniors in a multicultural neighbourhood. In Denzin, N K, Faust T (eds.) Studies in symbolic interaction (studies in symbolic interaction, vol. 37), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley: 63-78. [ Links ]

Müller T, Smets P (2009) Welcome to the neighbourhood: social contacts between Iraqis and natives in Arnhem, The Netherlands. Local Environment 14 (5): 403-415. [ Links ]

Pinkster F M, Völker B (2009) Local social networks and social resources in two Dutch neighbourhoods. Housing Studies, 24 (2): 225-242. [ Links ]

Rehberger E M (2009) Parallelgesellschaften – Das Scheitern der Integration von ethnischen Gruppen? Master thesis, University of Vienna, Faculty of Social Sciences. [ Links ]

Ross C E (2000) Neighborhood disadvantaged and adult depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(2): 177-187. [ Links ]

Ross C E, Jang S J (2000) Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: the buffering role of social ties with neighbors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28(4): 401-420. [ Links ]

Sampson R (1988) Local friendship ties and community attachment in mass society. American Sociological Review, 53: 766-779. [ Links ]

Sampson R J, Morenoff J D, Gannon-Rowley T (2002) Assessing Neighborhood Effects: social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28: 443-478. [ Links ]

Schlüter E (2011) Interethnic friendships of immigrants with host society members: revisiting the role of ethnic residential segregation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(1): 77-91. [ Links ]

Shafer K, McLoud L, Feldmann R L I, Moody J (2006) The impact of neighbor interaction: examining the role of social trust, pro-social behavior and neighborhood networks on perceived disorder. In: 101st Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association. Montreal. [ Links ]

Smets P, Kreuk N (2008) Together or separate in the neighbourhood? Contacts between natives and Turks in Amsterdam. The Open Urban Studies Journal, 1: 35-47. [ Links ]

Tolsma J, Van der Meer T, Gesthuizen M (2009) The impact of neighbourhood and municipality characteristics on social cohesion in the Netherlands. Acta Politica, 44(3): 286-313. [ Links ]

Turley R (2003) When do neighborhoods matter? The role of race and neighborhood peers. Social Science Research, 32: 61-79. [ Links ]

Verbrugge L M (1977) The structure of adult friendship choices. Social Forces, 56: 576-597. [ Links ]

Webber M M (1964) Urban place and the nonplace urban realm. In Webber M M, Dyckman J W, Foley D L, Guttenberg A Z, Wheaton W L, Wurster C B (eds.) Explorations into urban structure. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia: 79-153. [ Links ]

Wellman B (1979) The community question. The intimate networks of East Yorkers. American Journal of Sociology, 84: 1201-1231. [ Links ]

Wellman B, Wortley S (1990) Different strokes from different folks: Community ties and social support. American Journal of Sociology, 96: 558-588. [ Links ]

Zeggelink E P H (1995) Evolving friendship networks: an individual-oriented approach implementing similarity. Social Networks, 17: 83-110. [ Links ]

Received: July 2012. Accepted: March 2013.

FUNDING

This research has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2011) under grant agreement nº 216184 (GEITONIES PROJECT).

NOTES

i Please consult the first chapter of this special issue for general and methodological details on the research project GEITONIES.

ii It is important to note that, in the GEITONIES project, migrants were defined as persons of whom at least one parent had been born abroad and natives were persons with both father and mother having been born in Austria.

iii For the analyses in figure 1 to 6, significance has been assessed using chi-squared test, highly significant: p=0.000, significant: p>0.000 and <0.05.

iv In total, 77 alters out of 2,005 cases are interethnic relatives (mostly Austrian alters of migrant respondents).

v Figures 4, 5 and 6 only show the shares of in the neighbourhood. Similar to the previous figures, the other categories, which are not displayed for reasons of readability include: elsewhere in Vienna, elsewhere in Austria, in my country of origin and elsewhere abroad.