Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.101 Lisboa abr. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis7071

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Shopping malls and neoliberal trends in Southern European cities: post-metropolitan challenges for urban planning policyi

Centros comerciais e tendências neoliberais nas cidades da Europa do sul: desafios pós-metropolitanos para o planeamento urbano

Centres commerciaux et tendances néolibérales dans les villes de l’Europe du sud : les défis post-métropolitains à une politique de planification urbaine

Simone Tulumello1; Marco Picone2

1 Post-doc research fellow, Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa. E-mail: simone.tulumello@ics.ulisboa.pt

2 Associate professor, Department of Architecture, University of Palermo (Italy). E-mail: marco.picone@unipa.it

ABSTRACT Whilst shopping malls have been explored at length by critical urban studies, there has been little exploration of their role in restructuring the practice of urban and spatial planning. This article uses the shopping mall as an object of study in the light of the neoliberal trends and post-metropolisation in Southern Europe, with the aim of exploring challenges for urban governance and planning practice and with a focus on the role of the ongoing economic crisis. A threefold exploratory framework – the ‘lost-in-time scenario’, the ‘messianic mall model’ and the ‘(im)mature planning explanation’ – is used to make sense of the local versions of shopping mall development in Lisbon (Portugal) and Palermo (Southern Italy). According to findings, we highlight the clash between the multi-scalar nature of shopping malls and the dominance of the municipal scale in regulatory planning frameworks, and the risk that shopping mall development (at least in Southern Europe) may replicate uneven development patterns, reproducing the pre-conditions of the crisis without helping to overcome it. Keywords: Critical urban studies; comparative planning research; planning cultures; Southern European crisis; shopping centres.

RESUMO Embora os centros comerciais tenham sido estudados a fundo nos estudos críticos urbanos, poucas análises existem sobre o seu papel na restruturação da prática do ordenamento do território e do planeamento urbano. Este artigo utiliza os centros comerciais como objeto de estudo, com o objetivo de explorar os desafios para a governança urbana e o planeamento urbano em tempos de tendências neoliberais e pós-metropolitização na europa do sul, questionando, ao mesmo tempo, o papel da atual crise económica. Com o objetivo de melhor compreender as versões locais do sucesso dos centros comerciais em Lisboa (Portugal) e Palermo (Itália do sul), utilizamos um quadro teórico composto por três componentes: ‘lost-in-time scenario’ (padrões temporais de desenvolvimento económico), ‘messianic mall model’ (questões socioculturais) e ‘(im)mature planning explanation’ (culturas de ordenamento). De acordo com as evidências, realçamos o conflito entre o cariz multi-escalar dos centros comerciais e a dominância da escala municipal nos sistemas de ordenamento territorial; e o perigo que o êxito dos centros comerciais (pelo menos na europa do sul) possa replicar padrões de desenvolvimento desigual e, de consequência, reproduzir as pre-condições da crise sem contribuir à recuperação. Palavras-chave: Estudos críticos urbanos; estudos comparativos em ordenamento do território; culturas de ordenamento; crise da europa do sul; centros comerciais.

RESUME

Bien que les Centres commerciaux aient été étudiés à fond critiquement, il existe peu d’analyses traitant du rôle qu’ils peuvent avoir dans la rénovation de la planification territoriale. Les Centres commerciaux sont ici considérés comme des instruments permettant de comprendre les défis posés, en Europe du sud, par la gestion et la planification urbaines, en des temps de tendance néolibérale et post-métropolitaine et en considérant aussi le rôle de la crise économique actuelle. Pour tenter de mieux comprendre les versions locales du succès des Centres commerciaux, tant à Lisbonne qu’à Palerme, on a utilisé un cadre théorique à trois composantes : les types de développement économique se succédant dans le temps, les aspects sociaux-culturels et les types de planification. Ce qui a permis de montrer le conflit existant entre l’aspect multi-scalaire des Centres commerciaux et la dominance de l’échelle municipale dans la planification territoriale. Le succès des Centres commerciaux pourrait ainsi, du moins dans l’Europe du sud, faire renaitre des types de développement inégalitaires, en reproduisant les conditions antérieures à la crise, au lieu de contribuer à la récupération de celle-ci. Mots clés: Études critiques urbaines; études comparatives de planification territoriale; types de planification; crise de l’Europe du sud; Centres commerciaux.

I. INTRODUCTION: WHY MALLS IN SOUTHERN EUROPEAN CITIES ARE WORTH STUDYING Shopping malls have been explored at length in critical urban studies. Malls are said to manipulate shoppers’ behaviour (Crawford, 1992; Goss, 1993) and offer a ‘pseudopublic’ (Davis, 1990[2006]) or ‘post-public’ (Tulumello, 2015a) space capable of attracting visitors and customers, and therefore economies, from central urban areas. The effects of this capacity have been emphasised: the restructuring of urban retail systems (Jackson, 1996); the fortification and privatisation of public space, especially in central urban areas, as a response by municipal authorities (Sorkin, 1992; Orillard, 2008). Bromley and Thomas (1993) highlight issues of inequality, inasmuch as consumers with poor mobility are disadvantaged by the predominance of malls. Erkip (2005) sums up the critical issues: the social exclusion of some social groups and classes; the use of fear of crime to market the security of malls; the worldwide replication of standardised spaces; the influence of privatised shopping and leisure spaces on public recreational sites.

The shopping mall is a creation of Western Fordist society that has been able to survive post-Fordist transformation, becoming embedded in new urban trends in a postmodern, neoliberal era. Salcedo (2003: 1087) suggests that “the early fordist structure and appearance of malls, which facilitated standardized patterns of consumption, gave way to a post-Fordist segmented structure, in which new malls were created to satisfy specific and segregated needs based on new patterns of social stratification”. Tulumello (2015b: 15) suggests that the mall is resilient to urban transformation because of its capacity to mobilise “actors, resources and instrumental discourses in order to break planning rules and shape discursive practices and political debate”. One should add that, nowadays, malls seem to be on the decline, especially in the Anglo-American context.iiIn this article, we take this a step further, using the mall as an object of study with the aim of understanding better some dimensions of contemporary neoliberal trends in Western cities undergoing the process of post-metropolisation (Soja, 2000; 2011). This is relevant for two reasons and with two purposes.

Firstly, the challenges for urban governance stemming from the success of malls have been neglected by planning research – exceptions are a special issue of Cities devoted to retail planning and urban resilience (Barata-Salgueiro & Erkip, 2014), and Filion and Hammond’s (2008) analysis of downtown malls in mid-sized cities. On the contrary, understanding the ‘effects of retail-induced spatial reorganization’ (Rabbiosi, 2011: 82) is a useful instrument for developing insights into the relation between post-metropolitan spatialities and multi-scalar/multi-level challenges for urban governance in fragmented institutional cultures. This is especially relevant in the context of the economic crisis, which, with specific evidence in Southern Europe, is not a ‘contingency’. The crisis needs to be understood rather in its structural roots as the result of long term trends of (uneven) economic development and the intensification of neoliberal trends (Lapavitsas et al., 2010; Hadjimichalis, 2011; Seixas et al., 2015), of which the mall-induced transformation of retail systems is a significant component. Secondly, we recognise the importance of comparative studies in building more nuanced and less provincial urban theories (Robinson, 2011), in understanding planning systems better, and in highlighting neglected aspects of planning systems and culturesiii(Getimis, 2012). From this perspective, the analysis of the local versions of a global entity such as the mall will prove to be especially useful. The article sets out a comparative study about the emergence of the shopping mall era and the relation between mall development and spatial planning in two cities in the ‘borderlands’ of urban theory (Baptista, 2013; Tulumello, 2015b): Lisbon in Portugal and Palermo in Southern Italy. The cases are interesting because, like most Southern European cities, they exhibit an unusual pattern in relation to global urban transformation. In both cities, the advent of malls and the restructuring of retail systems have occurred later than those in most Western cities – respectively in the 1990s and from 2009 onwards – yet (hence?) this restructuring has occurred with dramatic speed. In both cities, in the context of late and turbulent neoliberal transformation, the study of malls will be a way of understanding some contemporary challenges of spatial planning.The scientific contribution this article provides to the academic debate on shopping malls revolves around an interpretive model that seeks to answer one question: what sets Southern European shopping malls apart from the traditional trend of mall development in Western countries? In other words, is there any particular reason why some cities have recently experienced a marked increase in the diffusion of shopping malls, at the same time as the idea of the shopping mall has started to lose favour elsewhere in the Western world? in order to provide an answer to these questions, the article presents, and employs for empirical exploration, three arguments, which can be summarised as: (1) the ‘lost-intime scenario’; (2) the ‘messianic mall model’; and (3) the ‘(im)mature planning explanation’, respectively referring to: (1) temporal patterns of development; (2) societal specificities; and (3) planning systems and cultures.

The article is set out in four sections. Section II reviews literature about post-metropolitan transformation in Western cities in order to address the challenges connected with the analysis of shopping malls. Section III presents the exploratory framework used in section IV to frame the success stories of shopping malls in Lisbon and Palermo, before setting out some concluding remarks (section V).II. MALLS, POST-METROPOLITAN TRANSFORMATION AND CHALLENGES FOR URBAN GOVERNANCE (Western) cities have been undergoing significant changes during the last few decades, as a result of globalisation forces and urbanisation, hegemonic powers and democratisation paths. From a spatial perspective, Martinotti (1993) depicts the grande trasformazione, that is, the consolidation of metropolisation patterns, as a result of the ‘third wave’ of global urbanisation (Scott, 2011). From a socio-cultural perspective, the concept of postmodernity has been used to highlight trends such as the end of the hegemony of common values and the loss of cultural frames of reference (Foster, 1983[1985]). From the perspective of urban governance, the decline of Fordist economies and deindustrialisation, together with the resulting fiscal stress, have been putting public sectors in crisis, making concepts like the decline of nation states and the fragmentation of decision-making processes necessary for understanding contemporary urban policies (Filion, 1996; Governa, 2010). Radical geographers have criticised the neutrality of analyses grounded in the concept of postmodernity, suggesting that recent urbanisation trends should be conceived within the frame of the emergence of a neoliberal project, in relation to the reorganisation and financialisation processes of global capital and patterns of uneven development (Jessop, 2002; Harvey, 2006). Soja (2000) developed the concept of ‘post-metropolisation’ in order to make sense of multi-scalar regional urbanisation processes, profoundly different from the processes of metropolisation. The idea of post-metropolisation goes beyond ideas such as the urban/non-urban duality, or density as a core indicator of the urban condition. In the city-region approach theorised by Soja,iv density and urban complexity can be found in different guises all through the urban agglomerations. From a theoretical perspective, critical debates about neoliberal trends and post-metropolitan transformation help us to make sense of the contemporary transformation of urban production and governance. Inasmuch as the aim of this article is that of taking some steps towards a productive dialogue between critical geographic and comparative planning studies, we recognise the issue of shopping malls as especially useful in analysing local replications of processes deeply embedded in mainstream globalisation and neoliberalisation patterns. The malls entail two types of challenge for urban studies and governance. Firstly, the local replications of globalised and homogenised lifestyles are a specific dimension of post-metropolitan urban ‘lives’. Beyond the critical approaches to the success of malls (see introduction), Cachinho suggests that the shopping mall is a useful space in order to “peer into the soul of consumactor” (2006: 34): the mall is a “residence, meeting point and place of celebration” for the postmodern consumer (2006: 34). Ozuduru et al. (2014) adopt a more complex perspective, deconstructing the encompassing concept of ‘postmodern consumer’ and substituting it with a fine-grain analysis of different social groups and their different choices. Fernandes and Chamusca (2014) focus on the shifting role of the shopping mall within urban transformation, distinguishing two phases, 1960s-1980s and after. The shift from metropolisation patterns towards urban renaissance and regeneration is reflected in the changing shopping attitudes: from “consumption as a symbol of status” towards “increase in leisure time” and “collective and individual varied forms of consumer over time” (2014: 173). Accordingly, the meaning of large retail spaces has been shifting from spaces of consumption to “spaces and places of life experience” (2014: 173).

Secondly, Fernandes and Chamusca (2014) set out some preliminary connections between critical/cultural perspectives and urban planning. Through a comparative analysis in four countries – France, Portugal, Sweden, Turkey – they focus on urban revitalisation after the 1980s, linking retail planning to the emergence of public-private partnerships and regeneration programmes (e.g. Those funded by the EU). Three socio-cultural and socioeconomic factors are highlighted for their role in the evolution of retail and urban planning: “(a) the relevance of the European Union and European values and policies; (b) political values and conceptions of local and regional planning systems; (c) social and ideological transformations such as market liberalization, changes in consumer behaviour and the increasing relevance of private stakeholders” (2014: 175).

To sum up, the study of challenges connected with the advent and success of malls can help shed some light on the contemporary processes of post-metropolisation, globalisation and neoliberalisation, thanks to the possibility of intersecting socio-cultural and political-economic factors with planning and urban governance trends. We recognise Eouthern Europe as a useful case in this respect because of its inherent peculiarities. We shall thus discuss the differences that set Southern Europe, and especially Portugal and Southern Italy, apart from most other Western countries with regard to shopping malls, setting out a conceptual framework useful for exploring these differences along three theoretical arguments.III. SOUTHERN EUROPEAN MALLS: AN EXPLORATORY FRAMEWORK Southern European cities have been experiencing rather specific, and turbulent, neoliberal and post-metropolitan trends. The late development of formal planning frames is often associated with disordered urban patterns and relatively low levels of spatial segregation (Abaci & Malheiros, 2010; De Leo, 2015). Late metropolisation, suburbanisation, fragmentation and polarisation trends have recently been hybridising urban territories (Abaci and Malheiros, 2010; Seixas and Albet, 2012). However, there has never been a high degree of speculation in the academia as to the reasons why Eouthern Europe has experienced unique trends in the diffusion of shopping malls. In this section, we will provide three exploratory arguments that could prove useful to explain this difference. Within all of them, we recognise the significant role played by the most recent economic trends, that is, the Southern European application of neoliberal diktats to the economic crisis that started in 2008; however, we also believe that there are other reasons to consider if one wants to truly grasp the rationale of what happened on a local scale. We are thus referring to a larger framework that takes the economic level into account, but mixes it with a socio-cultural perspective, in an approach that has been proven useful by critical geography and the cultural turn – see Péron (2001) for an application of a similar approach to urban retail transformation. The framework has an exploratory nature in that, rather than providing a conclusive theorisation, it is an instrument to be employed for empirical analysis – and subject to revision and adaptation to enable a better understanding of specific cases. The first argument is what we call the ‘lost-in-time scenario’. It is based on the idea that Southern European countries, for historical and socio-cultural reasons, have undergone a late economic development pattern compared to other leading European countries. Specifically for our case studies, the late democratisation of Portugal (Costa Pinto, 2006) and the criminal conditioning of local politics in Southern Italy (Cannarozzo, 2000; Bonafede & Lo Piccolo, 2010) have caused a significant delay in international investment necessary for the development of shopping malls. As we will discuss in the next section, there were no shopping malls in Palermo until 2009, something probably unique in the European context. This could easily justify a theoretical speculation that projects our case studies backwards in time – e.g. as if Palermo was simply experiencing in the 2010s those trends that other European areas had experienced earlier. Within this framework, one might be tempted to predict the future development trends of shopping malls in Portugal and Southern Italy by observing what is happening in the UK or in Germany today. However, this is not straightforward, as the European economic crisis is affecting Southern European cities and causing them to deviate from the path other countries have followed so far. There is a mainstream discourse about the crisis of Southern European countries (Blyth, 2013), according to which profligate public spending and ‘inaptitude’ for development are the reasons for ongoing difficulties. However, the Southern European crisis should be understood rather as the culminating point of a long-term process of uneven economic development in Europe (Lapavitsas et al., 2010; Hadjimichalis, 2011). The crisis has accelerated the trend for divergence, which had, since the early 2000s, blocked and reversed the convergence trends of the 1990s (Pinho et al., 2011). Existing analyses of the impact of the crisis on urban territories in Portugal highlight the existence of two consecutive crises (Ferrão, 2013; Seixas et al., 2015): between 2007 and 2010, the financial crisis especially affected the urbanisation economy (construction, real estate) and the urban areas most dependent on them; after 2010, the effect of the crisis sprawled to the general urban social fabric, austerity policies implemented at the national level being among the key drivers. In general terms, however, we want to highlight how the ‘lost-in-time scenario’ may be the first possible explanation, albeit an easy one, to account for the peculiarities of our cases. The second argument we will discuss, the ‘messianic mall model’, is based on the representation and the perception of shopping malls in urban contexts that are traditionally deprived of public spaces (Picone & Lo Piccolo, 2014); therefore, it links with recent critical approaches to urban studies (see, among others, Soja, 2000; Brenner and Keil, 2005; Rossi & Vanolo, 2012). The representation of malls in the Southern European context seems to differ slightly from the traditional one of places where citizens can meet in an environment free from the ‘outer world’ dangers (Crawford, 1992; Davis, 1990[2006]). Within our interpretative model, shopping malls are presented rather as a panacea for economic and social ills. This seems to reach a peak of rhetorical manipulation in those cities that lack alternative public spaces that can suit the residents’ needs and expectations. In these cases, the shopping mall becomes a sort of proclamation of deliverance, an ideal solution to provide the population with a place to meet and socialise. The ‘messianic mall model’ considers shopping malls as ‘pseudo-public’ (Davis, 1990[2006]) creations that are somehow capable of deceiving the perceptions of people, often due to the rhetorical wits of unscrupulous stakeholders and to the corrupt complicity of politicians. These rhetorical claims may be deconstructed and analysed to uncover a possible explanation for the peculiar trends that Portugal and Southern Italy exhibit. One could point out that the ‘messianic mall model’ framework could be applied to most Western contexts, and it is not a peculiarity of Southern Europe. Although this is partially true, we maintain that this process is particularly fostered in those social contexts where the incapacity (or complicity) of local government and the presence of powerful criminal groups are mirrored in a relatively weaker affirmation of public values and goods. Our third exploratory argument is the ‘(im)mature planning explanation’, which builds on the comparative studies launched by the publication of the EU Compendium of Spatial Planning systems (CEC, 1997). Southern planning systems show a predominance of the so-called ‘urbanism’ tradition; in Portugal mixed with a ‘regional economic’ one. In the urbanism tradition, “planning regulation is mainly undertaken through rigid zoning and statutory plans, while laws at the regulatory level are numerous, substantive and detailed. However, – and this is one of the overriding characteristics of Southern planning – an important gap exists between established plans and reality” (Giannakourou, 2005: 320). This is exemplified by the specificities of the Italian planning culture, where the gaps between intentions and outcomes, exemplary and ordinary experiences are especially evident (for an overview, see Scattoni and Falco, 2011): consider, for instance the stark contrast between world-acclaimed experiences in conservation planningv and the sprawling of illegal settlements in Southern Italian regions and cities (Laino, 2012; De Leo, 2015). For such reasons, Vettoretto (2009: 189) defines Italian planning as a “multifaceted and highly problematic field”. In Portugal, the previously mentioned late democratisation, having resulted in the late development of local authorities, is very evident in the patterns of institutional centralisation, lack of an intermediate administrative level between the state and municipalities, and lack of competency in local authorities (Crespo & Cabral, 2010). All in all, critical studies of urban governance and planning have highlighted generalised delays in innovation trends, low levels of public participation and poor accountability of decision-making (Bonafede & Lo Piccolo, 2010; Seixas & Albet, 2012; Picone & Lo Piccolo, 2014). For such reasons, Southern European planning systems are often referred to as ‘immature’ when compared to Central European traditions (CEC, 1997; Nadin and Stead, 2013). However, Janin Rivolin and Faludi (2005) refer to the tradition of urbanism as the ‘missing piece’ in the ‘puzzle’ of European planning – e.g. because of the focus on quality of space and urban design missing in other planning traditions. This is particularly meaningful in relation to the recent process of Europeanisation, especially evident in Italy during the 1990s – in relation to experiences such as the Urban Programme and negotiated programming (Gualini, 2001) – and in Portugal during the 2000s (Ferrão, 2011). The difficulty experienced in finding an agreement on the assessment of the Southern European planning systems, as well as their condition of ongoing change, suggests to us the need to overcome a simple duality between mature/immature planning systems and further comparative research.

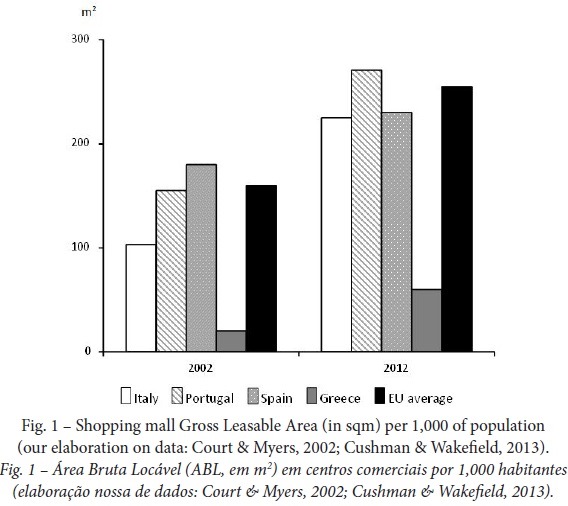

IV. SHOPPING MALLS IN LISBON AND PALERMO The figures of the total offer of Gross Leasable Area (GLA) in shopping malls in Southern European countries show a process of ‘catching up’ to European averages during the last decade (fig. 1 ), confirming the relatively recent success of shopping malls. Spain is an exception inasmuch as the boom of shopping malls came earlier – in 2002 GLA per capita was already above the EU average. This can be explained on the grounds of the construction and real estate bubble, created in the early 1990s, which reached its peak after the change of land-use laws in 1998 (Garcia, 2010). The burst of the bubble in 2008 can explain the fact that Spain is the only country in the sample where the shopping malls’ GLA grew more slowly than the EU average – the Portuguese real estate and construction bubble was not comparable in size to that of Spain (Seixas et al., 2015).

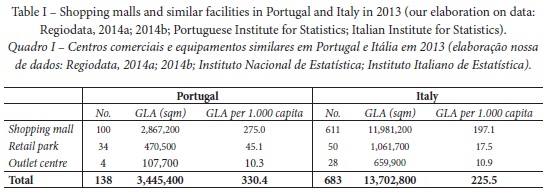

The main figures related to shopping malls and similar facilities in Portugal and Italy in 2013 are summed up in table I. In both countries, the interruption of the growth trends coincided with the economic crisis and between 2009 and 2013 the national stocks remained largely unchanged (JLL, 2014; Cushman & Wakefield, 2013). It must be noted that there may be further reasons for the interruption of the growth trends, such as market saturation. As such, the relation between retail trends and economic crisis needs to be investigated on a local level.

In fact, beyond global and Southern European trends, shopping mall developments and the transformation of urban retail systems are strongly dependent on local conditions: on cultural, social, political and urban governance dimensions. This section presents the histories of the success of malls in Lisbon and Palermo as a means of debating the relations between general trends, national conditions, and local specificities, planning arrangements and cultures.

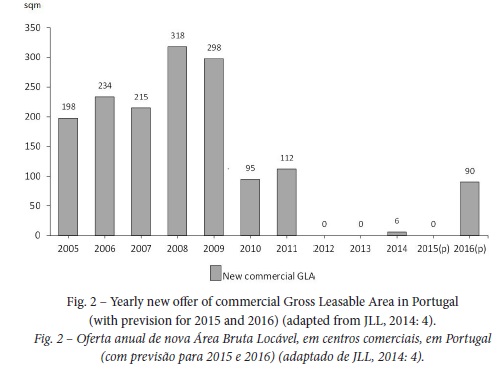

We have selected the case studies because they adhere, although in different ways, to the specificities depicted for the recent trends in Southern Europe. Lisbon, the main Portuguese metropolitan region (≅ 3 million inhabitants, ≅ 30% of national population) is a metropolis in turbulent transformation and unstable balance between an introverted past, marked by centralisation and top-down government, and late polarisation, suburbanisation, re-urbanisation, and gentrification (Tenedório, 2003; Seixas & Albet, 2012). The Palermo metropolitan area (1.1 million inhabitants) has a complex and unique history composed of the lack of effective planning regulations counterbalanced by some innovative practices in the 1990s (Cannarozzo, 2000; 2004). Also in Palermo, recent decades have been characterised by turbulent suburbanisation, polarisation, and fragmentation trends (Picone, 2006; Picone & Schilleci, 2013; Tulumello, 2015a). 1. Shopping malls in Lisbon; a Portuguese history An account of national processes is necessary for the understanding of the recent evolution of the retail system in Lisbon. The Portuguese shopping mall era began in the late 1980s, starting with Lisbon and Porto, and was consolidated during the 1990s.vi The growth has been sustained in the new millennium and the available stock of gross surface in big commercial facilities (of which 80% is in shopping malls) grew by over 150% between 2001 and 2009 (JLL, 2014: 26). Since 2009, the economic crisis has been reflected in a period of stagnation (fig. 2 ). According to Teixeira (2014), the difficulties for the sector are the result of the combination of the crisis – which has been dramatically reducing the purchasing power of the middle-class – with the market saturation stemming from the rapid growth of previous decades.

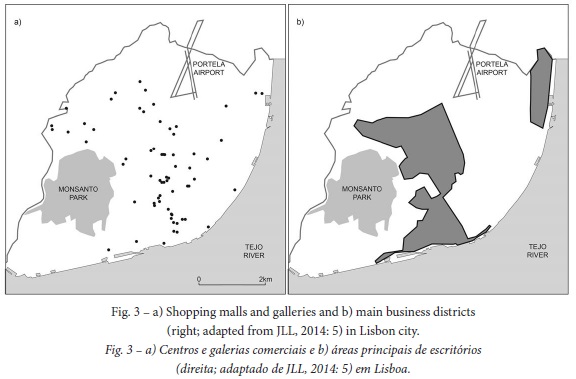

Shopping malls had already overtaken traditional shopping streets in dominating the retail system of the Lisbon metropolis in the early 1990s. In Lisbon city centre, the traditional downtown shopping district (Baixa) was replaced as the main centrality by a network of shopping centralities – malls and smaller galleries – on the axes of twentieth century urban development and the main business districts (fig. 3 ).

Our three exploratory arguments help us understand this boom. As for macro-economics, Portugal’s admission to the European Community in 1986, together with the international investment that it fostered, was crucial (Barata-Salgueiro, 1994). With regard to the socio-cultural issues, “in the case of Portugal there is a certain proximity with North American attitudes, with more liberal public policies than in most other European countries and with easy-going consumers who are seen to be more susceptible than most in Europe to publicity, technological gadgets and fashion” (Fernandes & Chamusca, 2014: 170). This can also be understood as the socio-cultural reaction of the Portuguese population, after 1974, to the end of a four-decade-long, obscurantist, authoritarian regime – the Estado Novo of António de Oliveira Salazar. As for spatial planning, Fernandes and Chamusca (2014) link the proliferation of shopping malls with the lack of inter-municipal cooperation and regional administration; municipalities compete in the name of economic growth, approving most commercial developments. Moreover, up to the 1990s, onerous rent control laws prevented international chains from entering the rental market, whereas malls were not subject to these limitations.vii>

Two cases are used to explore the relationship between shopping mall development and spatial planning policy in two different periods: the Colombo shopping mall, in Lisbon, completed in 1997; and the detailed plan for the El Corte Inglés in Cascais, in the western part of the Lisbon metropolitan area, recently approved. The Colombo mall is one of the three biggest malls in Europe with a gross surface area of 408,000 sqm, 400 stores in three floors, over 6,000 parking spaces. Built during the 1990s, its planning and construction procedures exemplify the process of the transformation of the retail system in Portugal and Lisbon. The Colombo mall has been defined as an “island of globalisation” (Cachinho, 2002: 148) and was designed to represent a European version of the American prototype mall: the image conveyed through advertising and architectural design is the well-known proposal of a place of encounter, a vibrant ‘world apart’ for urbanites. In the words of the developers: “we don’t perceive a shopping center any more as a place to buy products, we perceive a shopping center as we do the old downtowns of Europe, a social destination, where you go for pleasure and to have fun”.viii The analysis of the planning and building proceduresix shows several anomalies, providing some hints of how powerful interests for the transformation of the retail system were capable of bypassing the planning regulations and the advice of the technical departments. In 1988, following a concern expressed by the Department of Urbanisation about the increase in traffic flow, the municipality rejected the first project. The 1989 municipal elections resulted in a change of government – from centre-right to centre-left. The newly elected government soon approved a new project with double the gross surface – hence capable of producing even bigger traffic flows. In 1992, the municipal department responsible for strategic planning asked for a revision of the project, stressing that the blind façades may have brought about safety issues in the surrounding public spaces. However, the project was not changed and some thefts and robberies have been committed recently on public pavements around the shopping mall. The mall opened in 1997 when the municipal licence had not yet been granted because of some discordance between the design and the building, and some safety risks that were highlighted by the fire brigade. The history of the El Corte Inglés mallx exemplifies a case of mall development influenced by the current crisis. In 2002 the media reported news about an on-going projectxi for real estate development in Carcavelos parish, on the eastern fringe of the municipality of Cascais. In 2004, the municipal authority signed with MSF Inc. A protocol for the detailed plan of the new headquarters of the company. In 2007, MSF abandoned the project and sold the land to Aprigius Inc., which prepared a new detailed plan for a tertiary plant. In a municipal board meeting, a minority councillor asked whether the plan was being designed for the El Corte Inglés mall, according to what the media were speculating. The head of the department for Strategic Planning answered evasively, stressing that “detailed planning should be used to attract investments, with the aim of improving municipal competitiveness” (report of municipal board, 21.05.2007; our translation). The mayor added that informal negotiations were ongoing and stated that, anyway, he would have preferred the mall to be built in Cascais – hence taxes would be paid there – rather than in the nearby Oeiras municipality. In 2008 the national Ministry of Economy approved the project of the mall: a 14 floor building with a gross surface area of 194,000 sqm and almost 3,000 parking spaces. The parish authority of São Domingos de Rana – located near the area of the development – contested the project and highlighted two critical aspects (Junta de Freguesia de São Domingos de Rana, 2010): insufficient road infrastructure linking the area to the highway junction and a 95% soil sealing index of the parcel in the design. The authority emphasised how the proposed development did not abide by strategic and statutory planning indications at the municipal and regional levels, and would ‘overload and devalue’ an area that had been earmarked for tertiary development. The detailed plan was approved in 2011, despite the critical aspects highlighted by minority parties during the municipal assembly meeting: overbuilding of green areas; saturation of commercial facilities in the area;xiireconversion of a detailed plan for a tertiary plant into a commercial facility; traffic-related issues. During the debate, the mayor defended the project, suggesting that, in the case of rejection, the mall would have been built in a nearby municipality – hence Cascais would only have experienced negative externalities such as traffic congestion. In addition, competition between the parish authorities is evident in the procedure: the authority of the parish of Carcavelos (where the mall would be built) was favourable to the project, whereas the nearby São Domingos de Rana was against it. The findings from the case of El Corte Inglés gain further meaning when reconsidered in the light of Teixeira’s discussion (2014) on how the competition between malls (and their localities), which was already considerable because of market saturation, became ‘fierce’ in the aftermath of the crisis. This helps to explain the interest of local politicians in attracting a firm with global appeal such as El Corte Inglés – as well as the widespread interest of the media in the development.2. Shopping malls in Palermo, a unique case

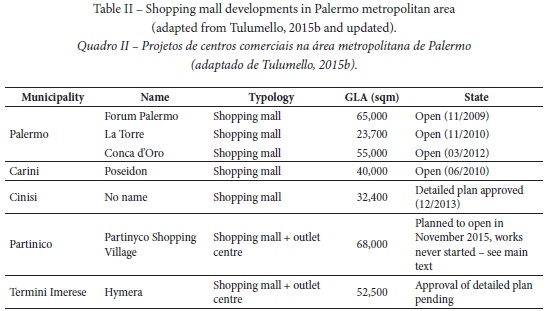

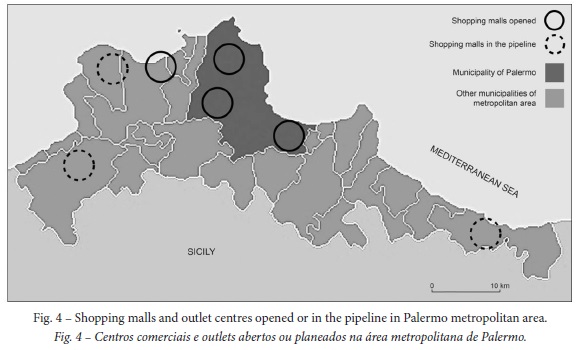

The case of Italy, and especially Southern Italy, is rather different from that of Portugal. Until the 1990s, the Italian retail system was dominated by small grocery stores, which pinpointed the urban fabric of most cities, spontaneous aggregations of small stores and few shopping centres serving networks of medium-sized cities (Péron, 2001). This can be explained by a combination of socio-cultural habits, including low female labour participation rates, the compact spatial configuration of cities and the restrictive regulations protecting small independent shops (Péron, 2001). The transition having been delayed even more than in Portugal, the new millennium has brought about a momentous process of catching up (fig. 1 ). Against this background, the case of Palermo is still unique for a very simple reason; up to the year 2009, Palermo may well have been the only European metropolis without a single shopping mall. This can be explained by the peculiar history of the city, which was characterised until the late 1980s at least by the dominance of criminality and corrupt politics (Cannarozzo, 2000). As a result, poor economic development and the absence of a productive and industrial fabric – see Trigilia (1994) about the failed development of Southern Italy –, together with a job market influenced by the use of nepotism in public jobs in order to achieve electoral consensus, turned Palermo into an unattractive city for investors. The 1990s represented a turning point in the history of Palermo. For the first time in decades, the city was governed by an uncorrupted centre left administration, which launched a socio-cultural and germinal economic development (Söderström et al., 2009). Although the first investments were made during the 1990s, the shopping mall developments were launched in the mid-2000s, in a new phase in which a centre-right administration brought back the old instances of manipulative politics, partially discarded during the 1990s (Bonafede & Lo Piccolo, 2010; Tulumello, 2015b). Although shopping mall development broke off at the national level at the start of the economic crisis, seven shopping mall and outlet centre developments have been carried out in the metropolitan area of Palermo (table II ): four centres have been opened and three are in the pipeline – although at least one may never see the light of day in the aftermath of the economic crisis (see below). An impressive gross leasable area (GLA) of 336,600 sqm would completely restructure the retail system of the metropolis. In fig. 4 , the location of facilities opened and in the pipeline shows how in a first phase, between 2009 and 2012, the majority has been concentrated in the core of the metropolis, whereas more recent developments will serve the peripheral areas. Following our interpretive model, we shall debate three dimensions: the timing of the processes and their relation to the economic crisis; the discursive construction of the malls; the planning procedures and local planning cultures.

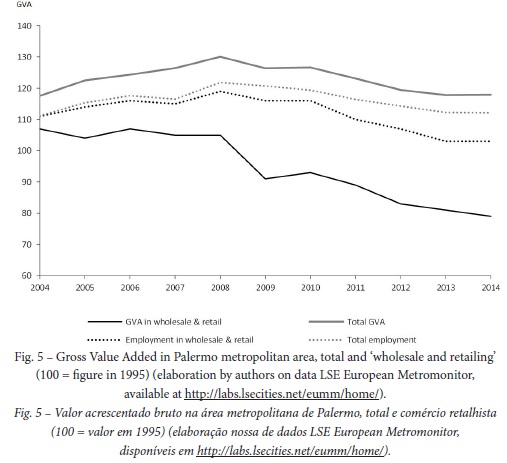

Firstly, the shopping mall era was launched at the same time as Palermo was being affected by the “worst recession Sicily had ever faced since WW2” (Fondazione Res, 2014: 1; our translation). The year 2010 has been the only year since 2007 without a negative growth rate – according to estimations made by Fondazione Res (2015), the year 2015 should have brought about the end of the recession. The aggregate reduction of metropolitan Gross Value Added (GVA) up to 2014 was 6.75% (fig. 5). The timing of the processes helps to shed some light on this situation. The interest of investors in undertaking shopping mall development in Palermo preceded the 2007 financial burst and was the result of a series of phenomena: the economic development during the 1990s; and the political reversal of the 2000s, which created the preconditions for the otherwise unfeasible planning procedures. In the first phase, the economic burst did not affect mall development and the opening of shopping malls pinpointed the period between 2009 and 2012. Despite this, the metropolitan GVA in wholesale and retailing fell by 24.8% between 2008 and 2014, whereas employment in the same sector fell by 13.4% (fig. 5 ). The only year of growth in the period was 2010 (GVA +2.2%; employment +0,0%) – this may be explained by the opening of the first three shopping malls (Forum Palermo, Poseidon, La Torre) and the end of the first phase of the crisis, before the explosion of the crisis in European sovereign debt in 2011. However, this did not affect the medium-term trends of the retail sector positively, suggesting that the success of the malls: (i) did not bolster an economic rebound (which, by the way, did not occur); and (ii) stemmed from transference from, hence the collapse of, the traditional retail market. Indeed, the association of the retailers of Palermo has reported a swift increase in the bankruptcy of traditional retailers since 2010; amongst them are several historic firms and cinemas, of which the latter have been substituted by multiplexes in the malls. In a second and more recent phase, there is evidence that the crisis had an effect on shopping mall development as well. The Himera mall has been awaiting the final approval of the detailed plan for a couple of years and the credit crunch has compromised the Partinyco Shopping Village, whose developers, with no bank willing to fund the operation, have recently launched the idea of a popular diffused shareholding in the city of Partinico – without success, so far.xiii

Secondly, the local discourse about malls shows some peculiarities when compared with the traditional mantras accompanying the social construction of malls. The offer of a social gathering place was accompanied by two types of discourse (Giampino et al., 2014; Tulumello, 2015b). On the one hand, the discussion depicted private investors ‘offering’ to the city those public spaces and services that public authorities were not able to guarantee, because of the disordered urban growth caused by a long-term absence of effective planning regulations. For example, during the inauguration ceremony of the Conca d’Oro mall in Palermo, residents of the immediate neighbourhood expressed their satisfaction, as the newly built mall would finally grant them a place to ‘spend the weekend along with the family’. The shopping mall is strategically built close to the ZEN, one of the most deprived and troublesome neighbourhoods in Italy; thus, it was quite easy for the municipality and the entrepreneurs to divert public attention from the issues and potential negative repercussions of the mall to the positive effect it claimed to exert on its surroundings. On the other hand, shopping malls were presented as tools for the ‘modernisation’ and ‘development’ of the city. These discussions created a general enthusiasm amongst the local media and civil society, especially evident on the occasion of the grand opening of the malls.

Thirdly, Tulumello (2015b) analysed the planning procedures through which the shopping mall developments have been carried out in Palermo city, underlining several anomalies and break-ups of statutory planning instruments, which may be interpreted from two perspectives. On the one hand, the case confirms some criticisms of the Italian planning system, characterised by the conflictual coexistence of a statutory framework and instruments introduced during the 1990s in order to shift the planning practice towards strategic models (Janin Rivolin, 2008). On the other hand, the flow of processes has shown oscillations between a lack of transparency and the use of rhetoric discourse to shape power relationships and create consensus around the developments. Local planning cultures seem to be shaped by ‘bargaining’ attitudes – not really surprising in the aforementioned new political context characterising the 2000s. All in all, the role of discourse about malls was crucial in order to shape public perception and justify irregular planning practices. The possibility for developers to present themselves as public benefactors was a paradoxical effect of the same opaque planning procedures that permitted the building of malls in spaces where they could not be built. The arrangements made in the protocols obliged the promoters to build some public services and spaces, or at least to promise to do so – as in the case of the Conca d’Oro mall, where, four years after the opening, the promised public services have still not been completed.

V. CONCLUSIONS The article used shopping malls as an object of study, with the aim of creating a better understanding of some dimensions of contemporary neoliberal trends for Western cities undergoing processes of post-metropolisation. It set out an exploratory framework around three arguments: the ‘lost-in-time scenario’, the ‘messianic mall model’, and the ‘(im) mature planning explanation’ – which respectively refer to peculiar temporal patterns of development, socio-cultural specificities, and planning systems and cultures in the context of Southern Europe, more specifically Portugal and Southern Italy. Within this exploratory framework, we compared the emergence of the shopping mall eras in Lisbon and Palermo, showing peculiar patterns in relation to global trends of urban transformation. All in all, the theoretical framework has proven a useful instrument in that it has been capable of highlighting both commonalities and local specificities, which we shall summarise. In both cities, the advent of the shopping mall has been delayed when compared to most Western cities – respectively in the 1990s and from 2009 onwards – mostly because of the late creation of conditions for large investments from (multi)national promoters. Since these conditions were achieved, however, the retail system has been overturned within a few years and, in the case of Palermo, not even the preliminary phases of the economic crisis have slowed down what might be defined as an explosion. This suggests to us a metaphor for the advent of shopping malls in a neoliberal, post-metropolitan era, a tentative theorisation that needs additional findings and more comparative studies in order to be generalised. In our cases, the advent and success of shopping malls needed a ‘critical mass’ of pre-conditions depending on factors at the national and local levels; once such a mass has been achieved, the effect was a ‘chain reaction’, which led to rapid and apparently uncontrollable transformation. The trends through which such pre-conditions were accumulated, however, are rather different and grounded on local specificities. In Lisbon, a temporal shift from restrictive periods towards neoliberal phases is key: the international investment boom following the admission to the European Community; the socio-cultural attitudes of a population empowered by the end of an obscurantist regime; and the territorial governance deregulation during the 1980s. In Palermo, a context marked by particularly turbulent trends, the key factors are the long-term lack of public services and quality of public spaces – hence the malls are represented as alternatives to this lack – and the clash between a complex planning system and the bargaining attitudes of local politicians. Two concluding remarks and further fields for analysis may be set out from the perspective of multi-scalar levels of planning practice and territorial governance, and the relationship between mall development and the Southern European crisis. On the one hand, shopping malls have been shown in their peculiar multi-scalar nature: they stem from global trends and investments; they are capable of influencing spatial and social organisation beyond the municipal level at the regional scale; however, in the institutional arrangements described, critical issues in planning practice stemmed from the crucial role of local planning cultures and municipal political decisions – unsurprisingly, the absence of a metropolitan authority with actual competence in land-use regulation characterises both cases. This calls into question the capacity of planning systems grounded on regulatory instruments at the municipal level to tackle vertical challenges in neoliberal times, suggesting the need for further exploration of multi-scalar arrangements in planning systems throughout (Southern) Europe. On the other hand, the specificities of Southern European discourse around malls, which stress issues of modernisation and development rather than safety and glamour, are especially powerful during the economic crisis, at least in its earlier phases. The evidence of municipal competition in the Portuguese case and the capacity of malls to restructure retail systems under recession are underscored by power relationships built, in the context of the crisis, through discourse about the need not to lose any opportunity for economic rebound. This is especially controversial in Palermo where the restructuring of the retail systems does not seem to have contributed to the rebound – quite the opposite. In fact, if we look back at critical analyses of the reasons for the Southern European crisis (Hadjimichalis, 2011; Blyth, 2013), the anti-crisis discourse around malls resulted in the replication of the very pre-conditions for the persistence of the crisis itself: malls foster polarisation (Jackson, 1996) and an economic recovery based on foreign investment (and profit) rather than local and endogenous development (hence resilient to external shocks). In this respect, the case of mall development confirms how mainstream discourse about the crisis plainly neglects its structural nature, calling for further critical exploration of the geographical patterns of crisis. The analysis of shopping malls carried out in this article, together with the two conclusions and spaces for further analysis, confirms that more dialogue between the perspectives of critical geography and comparative planning research is necessary. In our opinion, furthering such a dialogue through localised studies based on structural understandings of global trends is crucial to the better understanding of contemporary post-metropolitan transformation and to challenging neoliberal trends, together with the unjust, uneven spatialisation of urban production that they entail.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The article stems from the Italian National Research Programme (PRIN) “Post-metropolitan territories as emergent forms of urban space” funded by the Italian Ministry for Education and Research (MIUR). A first version of the article was presented at the AESOP 2014 Conference in Utrecht. Simone Tulumello is funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (SFRH/BPD/86394/2012). The authors wish to thank three anonymous reviewers for constructive critiques and comments.

REFERENCES

Arbaci, S. Malheiros, J. (2010). De-Segregation, peripheralisation and the social exclusion of immigrants: Southern European Cities in the 1990s. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36 (2), 227-255. [ Links ]

Baptista, I. (2013). The travels of critiques of neoliberalism: urban experiences from the ‘borderlands’. Urban Geography, 34 (5), 590-611. [ Links ]

Barata-Salgueiro, T. (1994). Novos produtos imobiliários e reestruturação urbana. Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, XXIX (57), 79-101. [ Links ]

Barata-Salgueiro, T. & Erkip, F. (2014). Retail planning and urban resilience – An introduction to the special issue. Cities, 36: 107-111. [ Links ]

Blyth, M. (2013). Austerity. The History of a Dangerous Idea. NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bonafede, G. Lo Piccolo, F. (2010). Participative planning processes in the absence of the (public) space of democracy. Planning Practice and Research, 25 (3), 353-375. [ Links ]

Brenner, N. & Keil, R. (Eds.) (2005). The Global Cities Reader. NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Brenner, N. & Schmid, C. (2013). The ‘urban age’ in question. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38 (3), 731-755. [ Links ]

Bromley, R. D. F. & Thomas, C. J. (1993). The retail revolution, the carless shopper and disadvantage. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 18 (2), 222-236. [ Links ]

Cachinho, H. (2002). O comércio Retalhista Português. Pós-modernidade, Consumidores e Espaço. Lisboa: GEPE. [ Links ]

Cachinho, H. (2006). Consumactor: da condição do indivíduo na cidade pós-moderna. Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, XLI (81), 33-56. [ Links ]

Cannarozzo, T. (2000). Palermo. Le trasformazioni di mezzo secolo. Archivio di Studi Urbani e Regionali, 67, 101-139. [ Links ]

Cannarozzo, T. (2004). Palermo: il martirio di un piano orfano. Archivio di Studi Urbani e Regionali, 80, 123-143. [ Links ]

CEC (Commission of the European Communities) (1997). The EU compendium of spatial planning systems and policies. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [ Links ]

Court, Y. & Myers, H. (2002). The development of shopping centres in Europe 2002. December 2002. Accessed 20.01.2016 www.test.icsc.org/international/EuropeReviewFINAL.pdf [ Links ]

Court Pinto, A. (2006). Authoritarian legacies, transitional justice and state crisis in Portugal's democratization. Democratization, 13 (2), 173-204. [ Links ]

Crawford, M. (1992). The world in a shopping mall. In Sorkin, N. (Ed.), Variations on a theme park: the new American city and the end of the public space (3-30). NY: Hill and Wang. [ Links ]

Crespo, J. L. & Cabral, J. (2010). The institutional dimension to urban governance and territorial management in the Lisbon metropolitan area. Análise Social, 197, 639-662. [ Links ]

Cushman, A. & Wakefield Research Publication (Eds.) (2013). Marketbeat. Shopping centre development report. Europe. Accessed 20.01.2016, em www.cushmanwakefield.pt/en-gb/research-and-insight/2013/european-shopping-centre-development-report-november-2013/ [ Links ]

Davis, M. (1990[2006]). City of quartz. Excavating the future in Los Angeles. London: Verso. [ Links ]

De Leo, D. (2015). About s-regulation. Or, the ‘Italian anomaly’. PRIN Issue Papers – February 2015 [MIMEO]. [ Links ]

Erkip, F. (2005). The rise of the shopping mall in Turkey: the use and appeal of a mall in Ankara. Cities, 22 (2), 89-108. [ Links ]

Fernandes, J. R. & Chamusca, P. (2014). Urban policies, planning and retail resilience. Cities, 36, 170-177. [ Links ]

Ferrão, J. (2011). O ordenamento do território como política pública. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [ Links ]

Ferrão, J. (2013). Território. In J. L. Cardoso, P. Magalhães, J. Machado Pais (Eds.), Portugal social de A a Z. Temas em aberto (244-257). Paço de Arcos: Expresso. [ Links ]

Filion, P. (1996). Metropolitan planning objectives and implementation constraints: Planning in a post-Fordist and postmodern age. Environment and Planning A, 28 (9), 1637-1660. [ Links ]

Filion, P. & Hammond, K. (2008). When planning fails: Downtown malls in mid-size cities. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 17 (2), 1-27. [ Links ]

Fondazione Res, (2014). Congiuntura Res. Osservatorio congiunturale della Fondazione Res. N. 1 – 2014. Accessed 20.01.2016, em www.resricerche.it/images/CRes/congiunturares_9_2014.pdf [ Links ]

Fondazione Res, (2015). Congiuntura Res. Osservatorio congiunturale della Fondazione Res. N. 2 – 2015. Accessed 20.01.2016, em www.resricerche.it/media/CR/congiunturares_luglio_2015.pdf [ Links ]

Foster, H. (Ed.) (1983[1985]). Postmodern culture. London: Pluto. [ Links ]

Garcia, M. (2010). The breakdown of the Spanish urban growth model: Social and territorial effects of the global crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34 (4), 967-980. [ Links ]

Getimis, P. (2012). Comparing spatial planning systems and planning cultures in Europe. The need for a multi-scalar approach. Planning Practice and Research, 27 (1), 25-40. [ Links ]

Giampino, A., Picone, M. & Schilleci, F. (2014). The shopping mall as an emergent public space in Palermo. Presented at Past Present and Future of Public Space – International Conference on Art, Architecture and Urban Design, Bologna (Italy), June 25 – 27. [ Links ]

Giannakourou, G. (2005). Transforming spatial planning policy in Mediterranean countries: Europeanization and domestic change. European Planning Studies, 13 (2), 319-331. [ Links ]

Goss, J. (1993). The ‘magic of the mall’: An analysis of form, function, and meaning in the contemporary retail built environment. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 83 (1), 18-47. [ Links ]

Governa, F. (2010). Competitiveness and cohesion. Urban government and governance’s strains of Italian cities. Análise Social, 197, 663-683. [ Links ]

Gualini, E. (2001). ‘New Programming’ and the influence of transnational discourses in the reform of regional policy in Italy. European Planning Studies, 9 (6), 755-771. [ Links ]

Hadjimichalis, C. (2011). Uneven geographical development and socio-spatial justice and solidarity: European regions after the 2009 financial crisis. European Urban and Regional Studies, 18 (3), 254-274. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (2006). Spaces of global capitalism. Towards a theory of uneven geographical development. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Jackson, K. T. (1996). All the world’s a mall: Reflections on the social and economic consequences of the American shopping center. The American Historical Review, 101 (4), 1111-1121. [ Links ]

Janin Rivolin, U. (2008). Conforming and performing planning systems in Europe: An unbearable cohabitation. Planning, Practice and Research, 23 (2), 167-186. [ Links ]

Janin Rivolin, U. & Faludi A (2005) The hidden face of European spatial planning: Innovations in governance. European Planning Studies, 13 (2), 195-215. [ Links ]

Jessop, B. (2002). Liberalism, neoliberalism, and urban governance: A state-theoretical perspective. Antipode, 34 (3), 452-472. [ Links ]

JLL (Jones Lang LaSalle), (2014). Mercado Imobiliário em Portugal. Análise 2013 / Perspetivas 2014. Escritórios/Retalho/Investimento. Accessed 20.01.2016, em www.jll.pt/portugal/pt-pt/research/24/mercado-imobili%C3%A1rio-em-portugal-2013-perspectivas-2014 [ Links ]

Junta de Freguesia de São Domingos de Rana, (2010). Plano de pormenor do espaço de estabelecimento terciário do Arneiro. Discussão pública. 27 October [MIMEO]. [ Links ]

Knieling, J. & Othengrafen, F. (2015). Planning culture – A concept to explain the evolution of planning policies and processes in Europe?. European Planning Studies, 23 (11), 2133-2147. [ Links ]

Laino, G. (2012). Which shadow in the ‘cities of sun’? The social division of space in the cities of the South. Bollettino del Dipartimento di Conservazione dei Beni Architettonici ed Ambientali, 12 (1), 343-356. [ Links ]

Lapavitsas, C., et al. (2010). Eurozone crisis: beggar thyself and thy neighbour. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 12 (4), 321-373. [ Links ]

Martinotti, G. (1993) Metropoli. La nuova morfologia sociale della città. Bologna: Il Mulino. [ Links ]

Merrifield, A. (2012) The urban question under planetary urbanization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37 (3), 909-922. [ Links ]

Nadin, V. & Stead, D. (2013). Opening up the Compendium: An evaluation of international comparative planning research methodologies. European Planning Studies, 21 (10), 1542-1561. [ Links ]

Orillard, C. (2008). Between shopping malls and agoras: A French history of ‘protected public spaces’. In M. Dehaene, L. De Cauter (Eds.), Heterotopia and the city. Public space in a postcivil society (116-136). Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ozuduru, B. H., Varol, C. & Ercoskun, O. Y. (2014). Do shopping centers abate the resilience of shopping streets? The co-existence of both shopping venues in Ankara, Turkey. Cities, 36, 145-157. [ Links ]

Parlette, V. & Cowen, D. (2011). Dead malls: Suburban activism, local spaces, global logistics. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35 (4) 794-811. [ Links ]

Péron, R. (2001). The political management of change in urban retailing. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(4), 847-878. [ Links ]

Picone, M. (2006). Il ciclo di vita urbano in Sicilia. Rivista Geografica Italiana, 113, 129-146. [ Links ]

Picone, M. & Schilleci, F. (2013). A mosaic of suburbs: The historic boroughs of Palermo. Journal of Planning History, 12 (4), 354-366. [ Links ]

Picone, M. & Lo Piccolo, F. (2014). Ethical e-participation: Reasons for introducing a ‘qualitative turn’ for PPGIS. International Journal of E-Planning Research, 3 (4), 57-78. [ Links ]

Pinho, C., Andrade, C. & Pinho, M. (2011). Regional growth transition and the evolution of income disparities in Europe. Urban Public Economics Review, 13, 66-103. [ Links ]

Rabbiosi, C. (2011). The invention of shopping tourism. The discursive repositioning of landscape in an Italian retail-led case. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 9 (2), 70-86 [ Links ]

Regiodata, (2014a). RegioData Shopping Center Explorer Italy. www.regiodata.eu/ [ Links ]

Regiodata, (2014b). RegioData Shopping Center Explorer Portugal. www.regiodata.eu/ [ Links ]

Robinson, J. (2011). Cities in a world of cities: The comparative gesture. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35 (1), 1-23. [ Links ]

Rossi, U. & Vanolo, A. (2012). Urban Political Geographies: A Global Perspective. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Salcedo, R. (2003). When the global meets the local at the mall. America Behavioral Scientist, 46 (8), 1084-1103. [ Links ]

Sanyal, B. (ed.) (2005). Comparative Planning Cultures. NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Scattoni, P. & Falco, E. (2011). Why Italian planning is worth studying. Italian Journal of Planning Practice, 1 (1), 4-32. [ Links ]

Scott, A. J. (2011). Emerging cities of the third wave. City, 15 (3-4), 289-321. [ Links ]

Seixas, J. & Albet, A. (Eds.) (2012). Urban governance in Southern Europe. Farnham: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Seixas, J. Tulumello, S., Corvelo, S. & Drago, A. (2015). Dinâmicas sociogeográficas e políticas na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa em tempos de crise e de austeridade. Cadernos Metrópole, 34, 371-399. [ Links ]

Söderström, O., Fimiani, D., Giambalvo, M. & Lucido, S. (2009). Urban cosmographies. Indagine sul cambiamento urbano a Palermo. Roma: Meltemi. [ Links ]

Soja, E. (2000). Postmetropolis. Critical studies of cities and regions. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Soja, E. (2011). Regional urbanization and the end of the metropolis era. In Bridge G, Watson S (Eds.), The new Blackwell companion to the city (679-689). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Sorkin, M. (Ed.) (1992). Variations on a theme park: The new American city and the end of the public space. NY: Hill and Wang. [ Links ]

Tenedório, J. A. (Ed.) (2003). Atlas da área metropolitana de Lisboa. Lisboa: AML. [ Links ]

Teixeira, J. A. (2014). The reshaping of retail landscape in greater Lisbon: Do shopping centers have a future? Presented at Regional development and globalisation: Best practices. 54th ERSA congress, Saint Petersburg (Russia), August 26-29. [ Links ]

Trigilia, C. (1994). Sviluppo senza autonomia. Effetti perversi delle politiche nel Mezzogiorno. Bologna: Il Mulino. [ Links ]

Tulumello, S. (2015a). From ‘spaces of fear’ to ‘fearscapes’: Mapping for re-framing theories about the spatialization of fear in urban space. Space and Culture, 18 (3), 257-272. [ Links ]

Tulumello, S. (2015b). Questioning the universality of institutional transformation theories in spatial planning: Shopping mall developments in Palermo. International Planning Studies, 20 (4), 371-389. [ Links ]

Uberti, D. (2014). The death of the american mall. The Guardian, 11 June 2014. Accessed 20.01.2016, em www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/jun/19/-sp-death-of-the-american-shopping-mall [ Links ]

Vettoretto, L. (2009). Planning cultures in Italy – Reformism, laissez-faire and contemporary trends. In J. Knieling, F. Othengrafen (Eds.), Planning cultures in Europe. Decoding cultural phenomena in urban and regional planning (189-203). Farnham: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Recebido: Junho 2015. Aceite: Dezembro 2015.

NOTES iAlthough the article should be considered a result of the common work and reflection of the two authors, Simone Tulumello took primary responsibility for sections I, II, and IV.1, and Marco Picone for sections III and IV.2, while conclusions (V) were written jointly. iiSome have suggested that the American mall is ‘dying’ (Parlette & Cowen, 2011; Uberti, 2014). iiiThe concept of planning cultures refers to the relations between visible planning products, the ‘planning environment’ (shared assumptions and values of actors) and the wider societal and cultural environment (Knieling & Othengrafen, 2015; see also Sanyal, 2005). ivIt should be pointed out that Soja has partially overcome his post-metropolitan theories (Soja, 2000) in order to embrace a ‘city-region’ approach (Soja, 2011) that seems to comply – at least partially – with other scholarly proposals such as Merrifield (2012) or Brenner and Schmid (2013). vEspecially important was the work of the ‘Parliamentary Commission for the Protection and Valorisation of the Historic, Archaeological, Artistic and Landscape Heritage’, better known as Commissione Franceschini (1964-1967). viAccording to Cachinho (2002), there were 48 malls in 1980, 417 in 1990, 789 in 2000. The figure is disproportionately big (table I ) because it is grounded on the national legislation (Portaria 424/1985), which defines shopping malls as retail facilities with 12 stores at least and a gross surface bigger than 500 sqm. Still, the figure gives an account of the temporal progression and shows how a system of larger malls and smaller galleries had been restructuring the Portuguese retail system in recent decades. viiSee www.europe.icsc.org/srch/Europeanawards1998/ea01.php [accessed 20.01.2016]. viiiAlvaro Portela, president of sonae imobiliária, interviewed in www.europe.icsc.org/srch/europeanawards1998/ea01.php [accessed 20.01.2016]. ixReconstructed through the original documents available at the Lisbon municipal archive. xReconstructed through the reports of meetings of municipal board (19.01.2004 and 21.05.2007) and assembly (24.01.2011). xiSee www.publico.pt/local/noticia/cascais-nao-quer-el-corte-ingles-173902 [accessed 20.01.2016]. xii11 big retail facilities exist on a 3 kms range (Junta de Freguesia de São Domingos de Rana, 2010). xiiiSee www.iltarlo.info/2015/12/10/partinico-shopping-center-un-progetto-mai-iniziato-e-che-sembra-sfumare-definitivamente/ [accessed 20.01.2016].

Todo o conteúdo deste periódico, exceto onde está identificado, está licenciado sob uma Licença Creative Commons

Todo o conteúdo deste periódico, exceto onde está identificado, está licenciado sob uma Licença Creative Commons