Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.103 Lisboa dez. 2016

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis7940

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Is there a rise of the territorial dimension in the EU Cohesion Policy?

Será que se verifica um incremento da dimensão territorial na Política de Coesão da UE?

La dimension territoriale est‑elle croissante dans la Politique visant à plus de Cohésion européenne

Eduardo Medeiros1

1Universidade de Lisboa, Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território (IGOT), Centro de Estudos Geográficos (CEG), Edifício IGOT – Rua Branca Edmée Marques, 1600‑276, Lisboa, Portugal. E‑mail: emedeiros@campus.ul.pt

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the role and importance of the territorial dimension of EU Cohesion Policy, during its five programming phases (1989‑2020), by relating this implementation process with several territorial elements, and by assessing their constant changes, namely in three main components and related elements: (i) the ‘policy strategy' designed to include an integrated territorial perspective; (ii) the ‘policy impacts' in territorial development and territorial cohesion, together with the use of territorial impact assessment procedures; and (iii) the focus on one or several ‘territorial scales', specifically through the support to multilevel‑governance, territorial cooperation, and place‑based strategies. Paradoxically, despite the continuous attempts to detach EU Cohesion Policy from its initial goals of promoting a more cohesive europe into a more neoliberalist paradigm type of ‘investment Policy', our analysis showed that the territorial dimension is still very much anchored with this Policy, and even gaining importance in several territorial related elements, such as the support to territorial cooperation and governance processes, and the use of territorial impact assessment procedures.

Keywords: territorial dimension; EU cohesion policy; territorial development; territorial cooperation; territorial impact assessment; territorial cohesion.

RESUMO

Este artigo analisa o papel e a importância da dimensão territorial da Política de Coesão da UE, ao longo das suas cinco fases de programação (1989‑2020), ao relacionar este processo de implementação com vários elementos territoriais, e ao avaliar as suas constantes mudanças, nomeadamente em três componentes principais: (i) a ‘estratégia política' desenhada de modo a incluir uma perspectiva territorial integrada; (ii) os ‘impactos da política' no desenvolvimento territorial e na coesão territorial, conjuntamente com a utilização de metodologias de avaliação de impactos territoriais; e (iii) o foco numa ou várias ‘escalas territoriais' especificamente através do apoio a processos de governança multinível, cooperação territorial, e estratégias de actuação localizada. Paradoxalmente, e apesar das sucessivas tentativas de dissociar a Política de Coesão da UE dos seus objectivos iniciais de promoção de uma Europa mais coesa, no sentido de implementação de um paradigma neoliberal de uma ‘política de investimento', a nossa análise concluiu que a dimensão territorial está ainda muito ancorada a esta Política, estando mesmo a ganhar uma importância crescente em vários elementos marcadamente territoriais, tais como o apoio a processos de cooperação e governança territorial, e o uso de procedimentos de avaliação de impactos territoriais.

Palavras‑Chave: Dimensão territorial; política de coesão da UE; desenvolvimento territorial; cooperação territorial; avaliação de impactos territoriais; coesão territorial.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article examine le rôle et l'importance de la dimension territoriale de la politique de cohésion de l'Union Européenne au cours de ses cinq phases de programmation (1989‑2020). On rapporte ce processus de mise en œuvre à plusieurs éléments territoriaux, et on évalue leurs changements constants, dans ses trois principaux composants: (i) la «stratégie politique» visant à inclure une perspective territoriale intégrée; (ii) les «impacts des politiques» sur le développement territorial et la cohésion territoriale, ainsi que l'utilisation des procédures d'évaluation de l'impact territorial; et (iii) l'accent mis sur une ou plusieurs «échelles territoriales», notamment par le soutien à plusieurs niveaux de gouvernance, par la coopération territoriale, et par des stratégies localisées. Paradoxalement, malgré les tentatives répétées de détacher la politique de cohésion de l'UE de ses objectifs initiaux de promotion d' une Europe plus cohérente, dans un type de paradigme plus néolibéral de «Politique d'investissement», notre analyse montre que la dimension territoriale est encore très ancrée dans cette politique, et gagne même en importance dans plusieurs éléments et contextes territoriaux, tels que le soutien à la coopération territoriale et de gouvernance, et à l'utilisation de procédures d'évaluation de l'impact territorial.

Mots clés: Dimension territoriale; la politique de cohésion de l'UE; le développement territorial; la coopération territoriale; évaluation de l'impact territorial; la cohésion territoriale.

I. INTRODUCTION

There is a large body of literature which discusses and illustrates the operationalization and effects of EU Cohesion Policy (ECP) as a mainstream EU Policy (Molle, 2007), as it has become an increasingly important financial tool to ‘mainly' help EU lagging regions. As its name indicates, this Policy was given birth (1988) with the main goal of promoting a more cohesive EU territory from a socioeconomic perspective, following the intentions expressed in the Single European Act. Indeed, while its ‘territorial dimension' was always present in several elements, like the definition of specific objectives devoted to the EU lagging regions, it was only after signing the Lisbon treaty (2009) that its scope was formally broadened by the inclusion of the territorial dimension of cohesion, alongside the social and economic dimensions.

This recognition of a need to go beyond the social and economic dimensions in designing, implementing, and evaluating ECP financed programmes, by following a more territorial, integrated, and holistic perspective, was often followed by a misleading notion of what is, in fact, this ‘new' territorial dimension, both by the scientific, the institutional, and political communities. For the most part, there is a tendency to add the ‘environmental dimension' to the ‘social' and the ‘economic' dimensions of development when ‘these communities' mention and analyse this territorial dimension, while neglecting crucial ‘territorial' dimensions such as ‘spatial planning' and ‘territorial governance'. In sum this article contributes to this conceptual discussion on the territorial dimension of policies and its main research questions are the following:

– What components should be taken into consideration when analysing the territorial dimension of policies?

– What has been the role and evolution of the territorial dimension in ECP from its beginnings to the present time, in its main components?

The analytical framework guiding the investigation is first set out in the second section of the paper, which identifies the main territorial components and related elements associated with ECP. The following section brings to the discussion the first analysed component: the Policy Strategy. Here, a concise overview of the influence of the EU spatial planning mainstream documents on ECP is provided, alongside the constant changes of these main strategic Policy goals, inspired by successive EU agendas and treaties. The following section seeks to investigate a second territorial ECP component: Policy impacts. In essence, this topic explores the degree of ECP impacts on territorial development and territorial cohesion in the EU Member‑states, as well as its role in supporting the use of Territorial Impact Assessment (TIA) evaluation procedures. The next section is dedicated to examine the last main component of our proposed methodology to assessing the territorial dimensions of policies: Territorial Scales. More precisely, this topic provides evidence on the importance of ECP in promoting territorial cooperation and governance processes, between all territorial levels. Finally, the last section applies the proposed methodology to assessing the territorialization degree of ECP, mostly based in the previous section discussion.

Methodologically, the research was carried out employing a content analysis approach of several EU documents, such as the Cohesion Reports, reports focusing on EU territorial trends (ESDP, Territorial Agendas, and ESPON Atlas), other related documents which evaluate the implementation of ECP, and a wide pool of available literature on this policy. In the end, a typology is proposed to measure the territorialisation degree of ECP.

II. UNCOVERING THE MEADING OF THE ‘TERRITORIAL DIMENSION' OF POLICIES

There is some awareness that the word ‘territorial' is gaining unprecedented usage and recognition within the EU institutions', political agenda and discourse. However, its meaning is often far from being straightforward. For one, this term is associated with a myriad of expressions associated with EU policy interventions, such as: (i) territorial development; (ii) territorial cohesion; (iii) territorial capital; (iv) territorial impact assessment; (v) territorial cooperation; and (vi) the territorial dimension of policies. Secondly, this notion closely mirrors the ‘more Anglo‑Saxon term': spatial. Finally, the likelihood of confusing ‘territorial' with ‘regional' term is off the charts.

In this context, we start this analysis by presenting a necessarily simplified overview of the meaning of the term ‘territorial'. Here, the Encarta dictionary is quite clear in relating it to ‘land or water owned or claimed by an entity, especially a government' (encarta, 2009). This goes along with the idea expressed by Peter Haggett (2001, p.16) that, “from the geographer's viewpoint the most evident territorial unit on the world's landscape is the modern nation‑state”. Also, it is evident that this notion (territorial) derives from the word ‘territory', which comes from the Latin term ‘territōrium'. This, in turn, fuses the notions of ‘terri' (earth) and ‘torium' (belonging to) (Moreno, 2002).

In this vein, and as Delaney (2009, p. 196) puts it, territory is, generically, “a bounded, meaningful social space the ‘meanings' of which implicate the operation of social relational power”. Nevertheless, the same author recognizes that there are “innumerable other generic forms and expressions of territory”, many of which implicate governance processes, in several territorial scales. Likewise, the related term ‘territoriality' “is used in a number of senses”, whilst it differs from the notion of ‘territory', as this “refers to behaviours related to the establishment and defence of territories” (Delaney, 2009, p. 196), or signifies an “attempt to affect, influence, or control actions, interactions, or access by asserting and attempting to enforce control over a specific geographic area” (Sack, 1983). Another significance found for this term is, for example, the sense of belonging to a given territory (Trigal, 2015, p. 586), amongst many others (Luukkonen & Moilanen, 2012; Martin, Rhys, & Michael, 2004).

Regarding the interconnection between the notions of ‘territory' and ‘space', Trigal (2015) advances a possible distinction where the former embraces a dimension with specific connotations, related with the sense of belonging and transformation (in a way in which societies are capable of organizing themselves), while the latter notion can be associated with providing an interpretive cohesion to the integrated knowledge of the elements in which societies are organized. In turn, based on several readings, Luukkonen & Moilanen (2012, p. 485), sustain that the term ‘space' has a more general meaning, and is mostly intertwined with ‘territories'. But, more importantly, they argue that territory “differs from a region in that its boundaries and the resources therein are under the control of people”. A more elaborated view on the notions of ‘region' and ‘space' can be found in Goodwin (2013), which launches a discussion on the notion of ‘relational region'.

Taken together, and although they might have different conceptual interpretations, all the above discussed notions (territorial, territory, space, and region) share a common trait, in the sense that they are strongly associated with ‘geographical analysis'. In our understanding though, the bulk of scientific literature does not always make a distinctive differentiation from the concepts of ‘space' and ‘place', and ‘territory'. For instance, the notion of ‘spatial planning' is used in very much the same way as the notion of ‘territorial planning'. Again, the notion of ‘spatial impacts' is used with similar meaning as the notion of ‘territorial impacts'. The difference here is the fact that the anglo‑saxon preference for the term ‘spatial' has led to a consistent use of this term in most of the existing ‘territorial related analysis', until some European Commission (EC) Reports started to make use of the term ‘territorial' in a more frequent manner. This is viewed by Roberto Camagnii, as a conquest of the south of Europe in the adoption of the term territory by the EU institutions.

Alongside, and in our understanding, the only significant difference between the terms ‘territory‘ and ‘region' is the fact that a regional perspective is, as the notion implies, specifically dedicated to the analysis of a certain or several regions. In other words, territory is a more general geographic term, which can cover several scales of analysis, such as the urban, the local, the regional, the national, and the European levels. Under this view, we could claim that the territorial dimension of a given policy is associated with its strategic guidance and operational capacity to produce development/cohesion impacts in certain territory in all dimensions of territorial development, be that land or/and water, managed by one or several entities or/and administration levels.

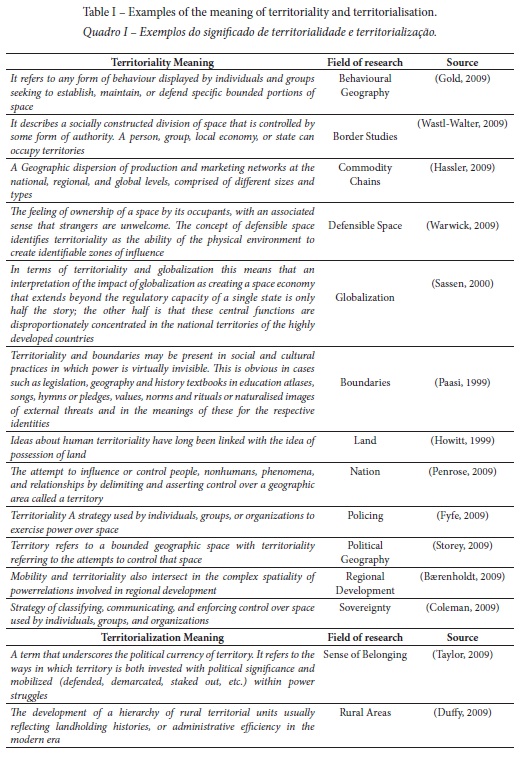

As previously stated, the term ‘territoriality' which, according to Kevin Cox, “has come to see as the very core concept of political geography – versus the apparently growing importance of network connections” (van der Wusten, 2009, p. 326), can have different meanings, depending on the research thematic focus (table I). More precisely, as Warwick (2009, p. 32) puts it, “territoriality has an extremely broad interpretation, from the concept of place attachment or social commitment to location, (…). Similarly, territoriality can be applied at a range of scales, relating to specific sites or wider neighborhoods”. Moreover, Paasi (1999, p. 73) reminds us that “it is portentous to note that the meanings of sovereignty and territoriality are also perpetually changing, implying that territoriality is not just a static, unchanging form of behaviour for a state”.

In its turn, territorialisation refers to a process of producing territorialities, while its opposite (Deterritorialisation) signifies “undoing and/or remaking of particular territorialities” (Coleman, 2009, p. 255). Regarding this concept, Figueiredo (2010, p. 11) relates it to the “design and implementation of programmes and projects with significant territorial impact, and whose priorities for intervention are defined according to strategic frameworks that have been formulated for the target territory, with the formal or informal participation of institutions and players identified for that territory”. Further, the same author adds that “it is not enough to consider that the investments or actions which embody it have a significant territorial impact.

A specific strategy must be in place that is designed according to the territory or with its participation. At the very least it should be prepared on the basis of a (greater or lesser) participatory forecast for that territory”. Put simple, this author relates the territorialisation of policies with its capacity to design tailor‑made strategies to specific needs of a given territory while requiring the participation of this territorial entity.

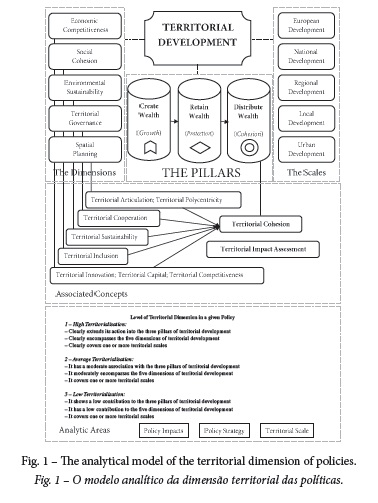

In our view, however, alongside the policy goals and related strategic execution, the territorialisation of a given policy depends on its effects in promoting territorial development and/or territorial cohesion. Finally, this policy has to target a specific territorial scale (from urban to European). In more detail, we define the territorialisation of a given policy as its ‘capacity to: (i) encompass the main dimensions of territorial development (fig. 1); (ii) effectively promote territorial development or cohesion (Medeiros, 2016a), and; (iii) target a specific territorial scale in its strategic intervention'. In simple terms, and following from this rationale, we propose three different levels of policy territorialisation; from high territorialisation capacity to a low territorialisation capacity (fig. 1).

III. THE TERRITORIAL DIMENSION IN EU COHESION POLICY STRATEGIES

1. The influence of EU spatial planning mainstream documents

If we classify the ‘modern' phase of ECP with the beginning of the multiannual programming periods, from 1989 onwards (EC, 2008), it is curious, at minimum, that it took more than two decades to include the territorial dimension of cohesion in the EU Treaty, by expressing the goal to “promote economic, social and territorial cohesion, and solidarity among Member States” (EC, 2010b, p. 17). In more detail, the article 174 expresses the desire to promote an harmonious development of the EU, by strengthening its economic, social, and territorial cohesion, and by reducing disparities between the levels of development of the various regions and the backwardness of the least favoured regions (rural areas, areas affected by industrial transition, and regions which suffer from severe and permanent natural or demographic handicaps such as the northernmost regions with very low population density and island, crossborder and mountain regions).

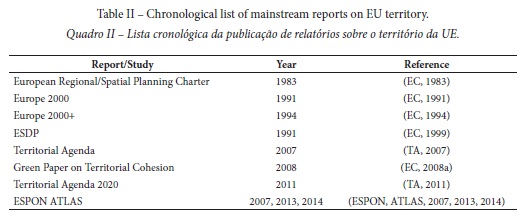

This long interregnum might suggest that the ‘territorial dimension' was largely neglected by the EU political agenda, for a long time. But that was not necessarily the case. At least, this dimension was not fully set‑aside. Indeed, if we relate the concern for this territorial dimension with the several EU attempts to implement ‘spatial planning' strategies, then we can conclude that this dimension has been in the EU political agenda since 1983, with the release of the European Regional/Spatial Planning Charter (EC, 1983), at the 6th session of the CEMAT, in torremolinos. In the following, and until the release of the ESDP (EC, 1999), the territorial dimension was included as an important coordinating factor of the EU sectorial policies during the Jacques Delors Presidency (1985‑1995) (Ferrão, 2010).

Since then, many other reports focusing on the EU territorial analyses were released (table II), while the Committee of Spatial Development (1991) and the Committee of the Regions (1992) were established (Medeiros, 2014a). Alongside, and after being in the making for around six years, the ESDP was released (Faludi, 2006). Finally, the two Territorial Agendas (TA, 2007; TA, 2011) and the Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion (EC, 2008b), maintained the debate around the need to promote a more balanced and harmonious development of the EU territory.

In the meantime, the ESPON (European Spatial Planning Observation Eetwork) Programme, established in 2002, gave a major boost to the territorial analysis of several EU policies. Amongst its main achievements are the production of methods, tools, and techniques with the goal to assess territorial impacts and effects of EU financed policies (Medeiros 2013a; 2014b; 2014c). Following from the above, the ESPON ATLAS, released in 2013, produced an overview of the territorial Dimensions of the Europe 2020 Strategy (EC, 2010c), and concluded that it is “essential that policy‑makers take into account the specificities of their place, their region or city in the implementation of policies contributing to the Europe 2020 Strategy. Not only by looking at the general scoring or ranking of individual regions related to the issues embraced by Europe 2020, but also by understanding the combination of all of these and possible mutual support” (ESPON ATLAS, 2013, p. 65).

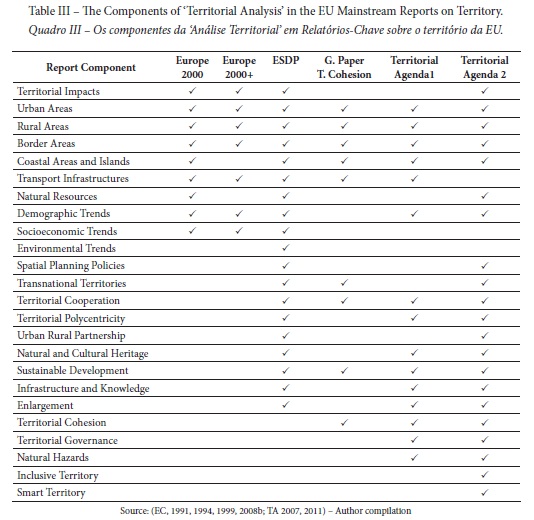

In short, the reading of the mentioned EU reports, which focus on territorial planning and territorial cohesion, leads us to conclude that all of them make a clear differentiation between urban and rural areas (table III), and that there is an increasing focus on certain ‘territorial analysis related elements' in the more recent ones, such as: (i) territorial cohesion; (ii) territorial polycentricity; and (iii) territorial governance. Also, in all of them there is always a clear reference to the need to promote a more balanced and harmonious territory, following from the idea expressed in the treaty establishing the European Economic Community (Rome – 1957).

Again, the ESPON Programme strengthened the knowledge of many of these ‘territorial analytic components', such as the: (i) territorial polycentricity; (ii) territorial impact assessment; (iii) urban‑rural relationship; (iv) demographic trends; (v) transport networks; (vi) natural hazards and risks; (vii) natural and cultural heritage; (viii) urban system; (ix) territorial governance; (x) environmental trends; (xi) socioeconomic trends;

(xii) rural areas; (xiii) maritime areas; (xiv) future territorial scenarios; (xv) land use pattern; (xvi) knowledge and innovation, and many others.

2. EU Cohesion Policy intervention strategies towards a more territorial and integrated approach?

Understandably, policies are not produced in a political vacuum. Indeed, ECP successive intervention strategies were largely influenced by the ‘époque prevailing political and economic context'. In short, the 1980s was marked by a series of events (the Single European Act, the EU accession of Greece, Spain and Portugal, and the adoption of the Single Market programme) which triggered a policy change towards a the goal of socioeconomic cohesion. In reality, for the most part, the reduction of regional disparities in development has been the guiding principle of ECP since the onset, and this is a clear territorial related objective. However, the “initial focus on unemployment, industrial reconversion and the modernisation of agriculture has broadened to include disparities in innovation, education levels, environmental quality and poverty, as reflected in the division of funding between policy areas. The process of reinterpreting development disparities is ongoing and may lead in future to a stronger focus on disparities in overall well‑being. In addition to the goal of reducing regional disparities, Cohesion Policy has become more closely aligned with the overall policy agenda of the EU” (EC, 2014, p. 200).

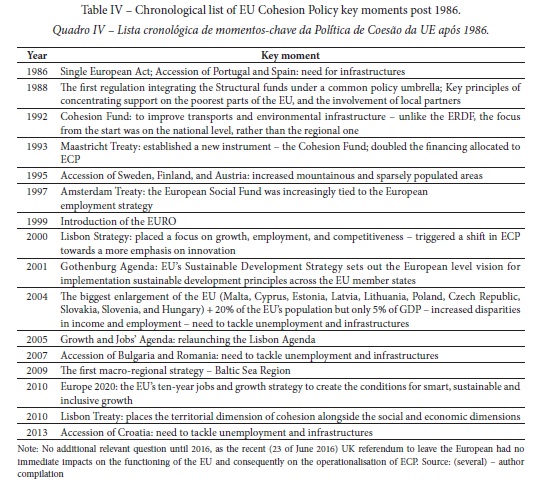

This constant adaptation of ECP main strategic goals was greatly influenced by accession phases of several EU Member‑States, and the adoption of EU development and growth strategies, and treaties (table IV). More specifically, while the 1990s ECP intervention strategies were characterized by the focus on improving trans‑European Transport Networks, in supporting the Single Market, and in improving environmental infrastructures, the adoption of the Lisbon and the Gothenburg Strategies brought a stronger emphasis on innovation and sustainability related issues. Here, while the former (innovation) can be labelled as a development component with little degree of territorialization, the latter (sustainability) can be associated with several policy areas with wide territorial character (environment, natural resources exploration, etc.).

In turn, the adoption of the Europe 2020, coined as the EU's growth strategy for the coming decade, is based on the underlying idea of implementing a smart, sustainable, and inclusive economy, in order to deliver high levels of employment, productivity, and social cohesion. In a flash, a cursory glance over the Europe 2020 strategic rationale might indicate a shift from the initial ECP goal of reducing regional disparities, due to the prevalence of the growth narrative, instead of the cohesion/development storyline. However, the territorial dimension continues to be present in the 2014‑2020 ECP programming cycle, as this policy continues to support policy areas with a clear territorial dimension (transport infra‑structures, environment, and urban development). Furthermore, the economic rationale underlying the ECP has become more integrated (EC, 2014, p. 201).

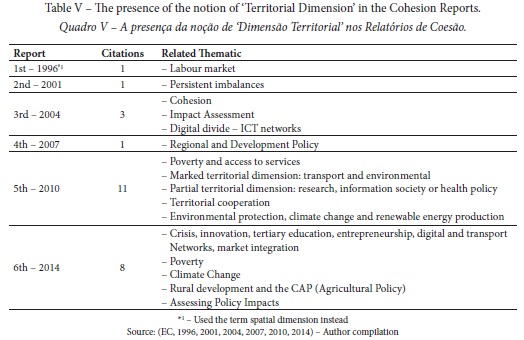

Another complementary overlook at the importance of the ‘territorial dimension' of ECP can be provided by the reading of the six published Cohesion Reports (table V). Crucially, a general overview of this table provides us a marked contrast with the baseline rational of this Policy, which has been strongly shifting from the ‘Cohesion' into a ‘Growth' perspective, since 2007. Curiously, the use of the term ‘Territorial Dimension' in the existing Cohesion Reports has increased over time, and is especially strong in the last two. Here, the fifth Cohesion report identifies several policies with marked territorial dimension, and others with partial territorial dimension. It also recognizes that there is a need to improve the territorial dimension from the impact assessment procedures of policies (EC, 2010). On its term, the sixth Cohesion report (EC, 2014) highlights the importance of the need to make use of the territorial dimension, with a sense that the effects of policy measures in several areas of intervention vary significantly across regions.

IV. THE TERRITORIAL DIMENSION IN EU COHESION POLICY IMPACTS

1. EU Cohesion Policy impacts on Territorial Development

We do not necessarily disagree with the argument that the “territorial dimension of ECP has not yet been fully taken into account” (Zaucha, Komornicki, Böhme, Swiatek, & Zuber, 2014, p. 249). Nevertheless, there can be no doubt about the importance of this policy in several dimensions, scales, and pillars of the Territorial Development concept. Also, the territorialisation of policies in the EU is far from being consolidated. To improve this scenario, the cited authors launch the concept of ‘Territorial Keys', with a view to translate the Territorial Agenda into a set of policy tasks. In sum, such keys are identified in order to guide policy‑makers, to highlight the role of the territorial structures for growth, to ensure a place‑based policy programming, and to make policy interventions more efficient (Zaucha et al., 2014)ii.

A vast number of sources provide crucial information on the impacts of ECP in the EU Member‑States. For instance, here, the EU Cohesion Reports make a complete synthesis on the effects of this Policy in several dimensions and components of territorial development. In more detail, the more recent ones (EC, 2010; EC, 2014) dedicate a full chapter to fundament the crucial role of ECP in promoting smart, green, and inclusive growth, based on existing evaluation reports, and on quantitative information on the direct outcomes of approved projects, and other physical indicators which are constantly monitored by the national Managing Authorities.

Based on the reading of these two Cohesion Reports, ECP has been a pivotal lever to support territorial development by financing measures which give support to enterprises (mostly SMEs) and innovation, as a motor of economic development, and by supporting social spending (human capital, job creation, social inclusion). Moreover, environmental protection measures are being supported not only by financing environmental infrastructures, but also through a direct stimulus to the use of renewable energy sources, and the promotion of energy efficiency measures. Furthermore, territorial articulation improvements have been financed in such areas as accessibilities (transport infra‑structures, urban public transports) urban and local development measures. Finally, territorial governance has received large support by measures which have improves institutional capacity, especially in less developed regions. As a consequence, the efficiency of public administrations and public services has been increased at all levels of administration (EC, 2014).

2. EU Cohesion Policy impacts on Territorial Cohesion

As the name suggests ECP, at its core, aims at reducing disparities in the EU territory. For the most part, the available literature identifies three different types of disparities: social, economic and territorial (Molle, 2007; Potluka, 2010; Leonardi, 2005). This rationale is, however, in our view, very much redundant, as the territorial dimension of development inevitably encompasses social and economic aspects. Nevertheless, Leonardi (2005, p. 6) is clearer on the role of ‘territory' as a fundamental aspect of ECP, as it: (i) helps to identify the place where the policy is implemented; (ii) proposes a territorial level for its implementation; and (iii) involves local and regional institutions. Alternatively, Molle (2007, p. 83) has a more econometric perspective of the meaning of territorial dimension, by proposing three major aspects of territorial disparities: (i) access to markets; (ii) access to know‑how and to innovation; and (iii) lack of access to certain services.

Despite the recent trends of ECP to evolve into a type of ‘investment' Policy, in contrast with its own designation, as the associated Funds (European Regional Development Fund, European Social Fund, Cohesion Fund, European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, and European Maritime & Fisheries Fund) have started to be officially known as ‘European Structural & Investment Funds' since 2014, this does not erase all its positive contributions to promote cohesion processes in the EU territory. Does this signify that ECP is less and less about ‘cohesion' and more and more about ‘investment' at its core? Here, the reading of the most recent EU regulation laying down common provisions on the European Cohesion and Investment Funds continue to base its intervention rationale on the Article 174 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which highlights the need to strengthen the economic, social, and territorial cohesion of the EU territory (EC, 2013b; Medeiros, 2014d).

In this context, there is no reason to believe that that ECP is no longer a crucial tool to achieve the goal of territorial cohesion expressed in the Lisbon Treaty. However, we can dispute the idea that this goal is a mere utopia in a globalized word, which hardly favours a more balanced and harmonious territorial development, towards the goal of territorial cohesion. In this regard, one has to start by defining what is the exact meaning of ‘territorial cohesion' which, as Clifton, Díaz‑Fuentes, & Fernández‑Gutiérrez (2015) conclude, is a complex and evolving concept (Farinós, 2015). Indeed, for, Elissalde, Santamaria, & Jeanne (2013, p. 644) “the notion of territorial cohesion has today become central to all cohesion policies. The objective of territorial cohesion is underpinned by notions that are linked, such as balanced spatial development, peripherality, general interest services and accessibility”. In this regard we have been proposing, for a long time (Medeiros, 2016a), the following definition: the process of promoting a more cohesive and balanced territory, by: (i) supporting the reduction of socioeconomic territorial imbalances; (ii) promoting environmental sustainability; (iii) reinforcing and improving the territorial cooperation/governance processes; and (iv) reinforcing and establishing a more polycentric urban system.

Under this view, available studies on the main impacts of the ECP in several Member‑States (Portugal, Spain, and Sweden), concluded that, despite the pivotal positive impacts of the ECP in promoting territorial development in all its main dimensions (mainly in the promotion of socioeconomic cohesion and environmental sustainability), it was not sufficient to counteract the perennial territorial trends which favour the development of the main urban agglomeration areas in the EU territory, vis‑à‑vis the peripheral and less populated areas. As such, the concretization of the goal of territorial cohesion in the EU requires not only additional funding to support the development of lagging regions, but also a clear territorial strategy which can beneficiate, for instance medium‑towns, as EU development anchors, towards a more balanced and polycentric territory (Medeiros, 2013; 2016b; 2016c).

3. EU Cohesion Policy impacts on Territorial Impact Assessment procedures

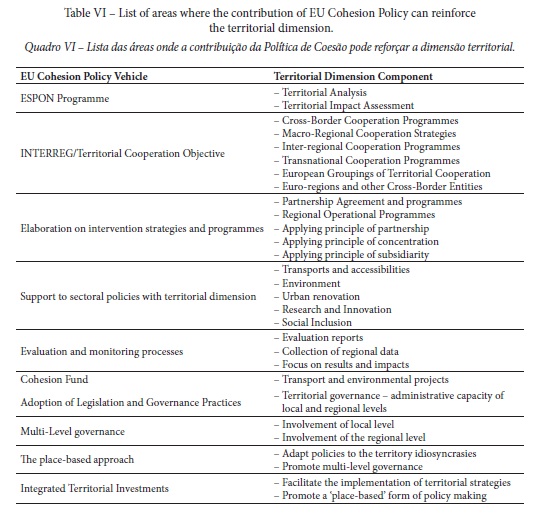

Alongside the role of ECP in promoting territorial development and in attempting to achieve the goal of territorial cohesion, the territorial dimension of this policy can be analysed from additional prisms (table VI), which include ‘major vehicles' which bring the territorial dimension of this policy into play. To start with, the implementation of this Policy requires systematic monitoring and evaluation procedures. Here, the use of Territorial Impact Assessment (TIA) procedures has been gaining ground on a steady but persistent manner (Medeiros, 2014c). Associated with this fact are the studies and reports produced under the auspices of the ESPON Programme, which extend their territorial analysis to several other ‘territorial related themes'. Likewise, EU institutions (mostly the European Commission and the Committee of the Regions) have been producing studies with a strong geographical perspective, including the Cohesion Reports, which analyse many domains of ECP, at the national and regional levels.

Indeed, the recognition of the need for better and more complete Policy evaluation procedures has always been at the heart of all the programming phases of ECP. And one can state that the rise of the TIA procedures in the ‘EU Policies impact evaluation evidences' is a direct result of the ECP support to the ESPON Programme. As a consequence, EU bodies and the respective policy evaluation units are more and more closely aligned with the need to use more holistic methods of Policy impact evaluation, as they recognize the limitations posed by the use of macro‑econometric evaluation tools. In sum, these trends present an additional contribution of ECP to bring to the fore a territorial dimension in the field of Policy impact evaluation.

V. THE TERRITORIAL DIMENSION IN EU COHESION POLICY IN ENCOMPASSING ALL TERRITORIAL LEVELS

1. EU Cohesion Policy impacts on Territorial Cooperation

One crucial way to assess the degree of Policy territorialisation is the potential capacity of a given policy to engage in all (from urban to continental), or in a specific territorial scale. In this regard, the implementation of ECP follows the EU principle of subsidiarity, which aims at determining the territorial level of intervention which is most relevant in the areas of competences shared between the EU and the EU Member‑States. Furthermore, the support given by ECP to regional Operational Programmes is illustrative of its territorial dimensional character.

In addition, ECP has been the main driver in promoting the implementation of ‘Territorial Cooperation' processes in the European territory. These territorial experiments, which can be defined as processes “of collaboration between different territories or spatial locations” (Medeiros, 2016d, p. 10), are probably the most relevant territorial related elements associated with the implementation of ECP. This importance can take several perspectives. For one, territorial cooperation involves the full scope of the EU territory, through the transnational cooperation process (former INTERREG strand B). But the cross‑border cooperation (INTERREG strand A) is, by far, the most significant territorial cooperation process within the EU, as the EU border regions cover 60% of the EU territory (NUTS 3), and more that 40% the total inhabitants (Medeiros, 2010). In addition, and more recently, this territorial cooperation process has been taken into another level following the implementation of macro‑regional strategies (Baltic‑Sea Region, Danube, Adriatic and Ionian, and the Alpine‑Macro Regions) (EC, 2013a).

As mentioned in the previous section, ECP had a crucial role in supporting regional development processes in the EU, namely by financing EU regional Operational Programmes. It also goes without saying that a large part of the financial aid given to the objective of territorial cooperation (former INTERREG), in the three strands (cross‑border, transnational and interregional cooperation), had not only a key role in reducing the barriers posed by the presence of borders (Medeiros, 2011), but has also provided a stable arena for the emergence of euro‑regional and macro‑regional entities all over Europe (Medeiros 2013b; Perkmann, 2003; Perrin, 2010), and more recently, provided a stable ground for the establishment of European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC) (De Sousa, 2013; CR, 2014).

2. EU Cohesion Policy and the place‑based approach

Another critical territorial element of ECP is its potential contribution to instil a place‑base narrative, in its implementation, following the suggestions presented in the ‘Barca Report' (Barca, 2009). In simple terms, this place‑based vision reformulates the key objective of ECP into tapping the under‑utilized potential of all EU places (Mendez, 2013). Understandably, this narrative has a clear territorial perspective, and recognizes that econometric studies do not offer any conclusive general answers on policy impact. At the same time, this approach intends to make use of ECP potential to reinforce the multi‑level governance processes, to explore EU‑wide networks for cooperation, and to disseminate operational experiences (Barca, 2009).

More generally, when it comes to the European Territorial Integration process, available literature holds that there is a certain ambiguity in its effect on the regional power, since sometimes it has positively affected empowerment processes in certain EU regions, while in other cases it has supported disempowerment processes (Bourne, 2003). In this line of reasoning, and according to Bache and Jones (2000), taking the UK and Spanish case, ECP influence on regional empowerment depends on three main things. In the first place, is the Policy Implementation Framework. Here, the introduction of the partnership principle changed the opportunity to structure the regional participation within ECP. In second place is the regional capacity to take advantage of available support from Policies. Understandably, this capacity varies from region to region (Rodríguez‑Pose & Garcilazo, 2015). Finally, in third place is the type of territorial structure of the state, and in particular the relation between the central state and the different peripheries. Again here, the EU territory encompasses a myriad of completely different situation cases (Arribas 2012; ESPON 2.3.2, 2006).

In the eyes of some, however, the architecture of ECP, which favours the implementation of a multilevel type of governance, leads to a gaining influence of sub‑national stakeholders (Faludi, 2010, p. 173). Likewise, the direct and indirect effects of this Policy in strengthening the territorial cooperation process, and in promoting sound territorial governance processes (Luukkonen & Moilanen, 2012), can act as a tool to promote local and regional empowerment, despite the fact that the EU is a “highly heterogeneous space in terms of institutional and governance issues, and in terms of both the different national and regional modes”. Conversely, Zaucha et al. (2014, p. 249) argue that “almost 20 years of intergovernmental cooperation on territorial development among EU Member States has barely reinforced multiannual programming in relation to EU development (cohesion) policy”.

VI. IS EU COHESION POLICY AN INCREASING TERRITORIALISED POLICY?

Based on the previous analysis, there are several evidences which point to the conclusion that, despite recent attempts to change the initial cohesion paradigm into an investment/growth epitome, the territorial dimension of ECP has been gaining ground throughout the last couple of decades (1989‑2020). Such a conclusion is supported by a plethora of arguments. Amongst them, is the crucial role of ECP in supporting all dimensions and components of territorial development, although with different intensity levels. In other words, ECP has been, and continues to be much more than a simple investment tool for economic growth, and while its influence differs from country to country, the continuous increase of its financial package adds to its growing territorialisation influence. In a similar way, ECP has backed the rise of TIA procedures in policy impact evaluation and also the territorial evidence analysis through the financing of the ESPON Programme.

Furthermore, ECP implementation strategies focus on promoting integrated territorial/placed‑based approaches, and territorial cooperation processes, have increased overtime. All of these can be seen in each Member‑States' Common Strategic Frameworks, where investments from the ESF, ERDF, or Cohesion Fund, finance more than one priority axis of one or more Operational Programmes. Simply put, at present, actions financed by ECP may be carried out by means of an Integrated Territorial Investment (an ‘ITI'), to foster a similar policy goal, for instance.

Again, ECP has a marked territorial dimension if viewed as a vehicle which promotes one or all territorial levels, via the: (i) application of the subsidiarity principle; (ii) support to cross‑border cooperation processes; (iii) support to place‑based development strategies; and (iv) support to multi‑level governance processes. Also, in the present programming period, there is a specific instrument which promotes community‑led local development projects, and another for financing integrated actions for sustainable urban development, both of which with a clear territorial scale in mind.

In this context, and if we apply the proposed methodology to assess the general level of territorialisation of ECP (1989‑2020), we can assume that it has had, along its life cycle, a high degree territorialisation, based on the following generic conclusions:

– It is clear that the interventions financed by means of this Policy touched all pillars of territorial development, as it not only provided solid ground for wealth generation (modernization and building of new accessibilities, socioeconomic, and environmental related infrastructures, and support to the human capital valorisation), but was also pivotal in retaining and distributing wealth by supporting job creation. One can, obviously, question the degree of the long‑term influence on the last pillar, as many of the jobs created were temporary and hardly well‑paid;

– It is more than clear that this Policy financed projects which can be associated with all the dimensions of territorial development, despite the fact that they were more concentrated in providing support to business development, human capital, infrastructure, research and innovation, and environment protection. Even so, territorial

cooperation and territorial governance processes were also improved with a share of ECP investments, as well as spatial planning related components, such as the improvement of territorial connectivity and articulation. As Faludi (2010, p. 183) puts it, sound spatial planning is vital for this Policy to take into account the most adequate locations for its interventions and the related opportunities and constraints.

– The positive role of ECP is also evident and relevant in covering and impacting several territorial scales, from the urban to the European levels. In this particular analytic component, the attention given by this policy to the regional level was particularly strong, mainly through the regional Operational Programmes. But here, the local level was also widely supported by specific initiatives as the Leader Community Initiative, for instance. Moreover, several large scale infrastructural programmes had a clear national perspective, and sometimes even a European dimension (transnational transport, energy, and cooperation networks).

VII. CONCLUSIONS

The simple fact that ECP aims at achieving a more cohesive EU territory connects it with a clear ‘territorial dimension'. To state otherwise is, in our view, to hinge on a simplistic and ungrounded perspective, which ignores the important role of this Policy in reinforcing the pillars and main dimensions of territorial development, in all the administrative levels of the EU. Alongside, this Policy has had, throughout its almost 30 years of implementation, a crucial role in providing financial support to sectoral policies with a strong territorial dimension (transports, environment, urban renovation, research and innovation, and social policies), and in supporting territorial cooperation and multi‑level governance processes. Furthermore, the elaboration of national and regional intervention strategies, which are necessary to have access to the available EU funds, together with the obligation to establish monitoring and evaluation practices with a territorial perspective, has led to a rise of the awareness of the need to make use of TIA techniques to assess EU policies main impacts.

Moreover, the multiplier effects of ECP in ‘touching' several elements of the territorial dimension are extensive to the academic community, and to the myriad of stakeholders involved in the operationalization of ECP (ESPON CaDEC, 2014). More precisely, the academic community has been involved in providing sound territorial knowledge on the effects and impacts of the investments associated with this policy, namely with the elaboration of reports and studies under the auspices of the ESPON Programme, and the programme's evaluation reports. Furthermore, the release of the mentioned Territorial Agendas, the Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion, the ESDP, and the Scenarios for Integrated Territorial Investments (EC, 2015), are proof of the awareness of the need to provide a more holistic, complete, integrated and territorial perspective, when implementing ECP related programmes.

All in all, and by making use of a methodology which takes into account the presence of several territorial related elements in a given Policy, and more precisely their close relation with the Policy strategic territorial intervention, potential territorial impacts, and the territorial focus on one or more territorial scales, we can conclude that there is a strong case to argue that ECP has a high level of territorialization. No less fundamental to this analysis is the critical role that this Policy has had in supporting the development of sub‑national administrative scales, and in particular the regional level, at least in less development EU countries. In this regard, the claims which require the need for a more place‑based approach to this Policy also unveil its substantial territorial dimension. Additionally, the increasing importance of the support provided through the financial support given to the territorial cooperation goal of this Policy unfolds a key territorial dimension, as the main strand of this goal (cross‑border cooperation) financially speaking covers more than 60% of the EU territory. Also, the rise of the macro‑regional strategies (four in late 2015), alongside with the constant establishment of the European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (55 in late 2015), provides further impetus to the reinforcement of territorial cooperation networks within the EU.

Finally, our own detailed analysis on the main territorial impacts of ECP in several EU Member‑States and regions, has revealed the pivotal role of this Policy in supporting several pillars of the territorial cohesion concept, and mainly in improving social, economic, and environmental related components in the intervention territories, with particular emphasis on improving the infra‑structural and the human capital domains. However, and despite the multiple positive direct and indirect impacts provoked by the programmes financed under the auspices of this Policy, the goal of achieving a more cohesive and balanced territory at the national level, has not been attained. On the contrary, despite a wider canalization of financial support to the less developed regions, the larger EU metropolitan areas continue to gain in their overall relative position, in terms of their socioeconomic and demographic attractiveness.

To conclude, and following from the above, we could see that, despite the constant reforms and reshapes, which have been attempting to push ECP further away from its initial goals as a cohesive policy, into a an investment policy, its territorial dimension is widespread and substantial in all the analysed components. Against this background, we can argue that, in order to reinforce this territorial dimension, this Policy needs further action from both the academic community and the involved political actors. The former are responsible for the continuation of efforts to highlight the need for better understanding the territorial impacts of this Policy, and to design better spatial development strategies, with an integrated territorial approach, and which launch concrete measures to achieve a more balanced, harmonious, and polycentric urban system within the EU territory.

On their part, the latter (policy‑makers) should be provided with better territorial analyses, and evaluation reports of the main territorial impacts of the EU Cohesion Policy, in order to make more rational and intelligent decisions on the necessary thematic concentration of the available investments. Also, the EU policy makers should be aware that relevant territorial impact assessment procedures require more than a simple press‑of‑a‑button gesture, and that the analysed territorial dimensions of policies extend the economy‑society‑environment triangle. Consequently, the investment in improving available statistical data collection is of crucial importance to better understand the policy causalities in all dimensions of territorial development.

In the end, the analysis presented intends to provoke an accelerated debate on the future trends of the ECP, and to highlight the need to take into account and reinforce its territorial dimension, and the consequent need to implement the proposals expressed in the Territorial Agenda, as a means to complement the ‘territorialess EU 2020 strategy'. Moreover, we expect that the academic and political discussion on the ‘territorial dimension' of the EU Cohesion Policy leads to a wider awareness on the importance of the geographical analysis of polices, in order to better understand their territorial impacts in all the dimensions of territorial development.

ACKOWNLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank Graça Rønning to the English revision of the text, and two anonymous reviewers for the extremely useful comments leading to a better organization of the article.

REFERENCES

Arribas, G.V. (Coord.) (2012). Division of Powers between the European Union, the Member States, and the Regional and Local Authorities. Brussels: European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA), Committee of the Regions. [ Links ]

Bache, I., & Jones, R. (2000). Has EU regional policy empowered the regions? A study of Spain and the United Kingdom, Regional & Federal Studies, 10(3), 1-20. [ Links ]

Barca, F. (2009). An agenda for a reformed cohesion policy: a place-based approach to meeting European Union challenges and expectations. Brussels: Independent Report prepared at the request of Danuta Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy, DG Regional Policy. [ Links ]

Bourne, A. K. (2003). The Impact of European Integration on Regional Power. Journal of Common Market Studies, 41(4), 597-620. [ Links ]

Bærenholdt, J. O. (2009). Regional Development and Noneconomic Factors. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, Vol. 9 (pp. 181-186). Conventry: Elsevier.

Clifton, J., Díaz-Fuentes, D., & Fernández-Gutiérrez, M. (2015). Public Infrastructure Services in the European Union: Challenges for Territorial Cohesion, Regional Studies, 50(2), 358-373. [ Links ]

Coleman, M. (2009). Sovereignty. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 9 (pp. 255-261). Conventry: Elsevier.

CR. (2014). EGTC monitoring report 2014. Implementing the Strategy Europe 2020. Brussels: Committee of the Regions /METIS. [ Links ]

De Sousa, L. (2013). Understanding European Cross-border Cooperation: A Framework for Analysis, Journal of European Integration, 35(6), 669-687. [ Links ]

Delaney, D. (2009). Territory and Territoriality. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 4 (pp. 136-145). Conventry: Elsevier.

EC. (1983). European regional/spatial planning Charter. Torremolinos Charter. Strasbourg: European Conference of Ministers Responsible for Regional Planning, [ Links ] adopted on 20 May 1983 at Torremolinos (Spain), European Commission.

EC. (1991). Europe 2000: outlook for the development of the community's territory. Luxembourg: Commission of the European Communities, Directorate-General for Regional Policy. [ Links ]

EC. (1994). Europe 2000+. Cooperation for European territorial development. Luxembourg: European Commission. [ Links ]

EC (1996) First report on economic and social cohesion. Luxembourg: European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (1999). European Spatial Development Perspective: Towards Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the EU. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [ Links ]

EC. (2001). Second Report on Economic and Social Cohesion. Luxembourg: European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2004). A new partnership for cohesion – convergence, competitiveness, cooperation, Third report on economic and social cohesion. Luxembourg: European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2007). Growing Regions, Growing Europe. Fourth report on economic and social cohesion. Brussels: European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2008a). EU Cohesion Policy 1988-2008: Investing in Europe's Future. Luxembourg: Inforegio Panorama 26, European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2008b). Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion - turning territorial diversity into strength. Brussels: European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2010a). Investing in Europe's future: Fifth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. Brussels: European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2010b). Lisbon Treaty. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union C83, Volume 53, 30 March.

EC. (2010c). EUROPE 2020 - a strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Brussels: Communication from the commission, 3.3.2010, European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2013a). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions concerning the added value of macro-regional strategies. Luxembourg: SWD(2013) 233 final, European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2013b). Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Luxembourg: Official Journal of the European Union, 20.12.2013, L 347/320, European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2014). Sixth Report on Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion. Investment for jobs and growth: Promoting development and good governance in EU regions and cities. Brussels: European Commission. [ Links ]

EC. (2015). Scenarios for Integrated Territorial Investments. Brussels: Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, European Commission. [ Links ]

Elissalde, B., Santamaria, F., & Jeanne, F. (2014). Harmony and Melody in Discourse on European Cohesion, European Planning Studies, 22(3), 627-647. [ Links ]

Encarta (2009) Microsoft Encarta Premium, Microsoft Corporation: Redmond: DVD-ROM. [ Links ]

ESPON, 2.3.2. (2006). Governance of territorial and urban policies from EU to local level. Luxembourg: Final report (31st May 2006), European Spatial Planning Observation Network.

ESPON, ATLAS. (2006). Mapping the Structure of the European territory. Luxembourg: European Spatial Planning Observation Network.

ESPON, ATLAS. (2013). T erritorial Dimensions of the Europe 2020 Strategy. Luxembourg: European Spatial Planning Observation Network.

ESPON, ATLAS. (2014). Mapping European Territorial Structures. Luxembourg: European Spatial Planning Observation Network.

ESPON, CaDEC. (2014). Capitalisation and dissemination of ESPON concepts. Luxembourg: Final Report, 10th March 2014, European Spatial Planning Observation Network.

Faludi, A. (2006). From European spatial development to territorial cohesion policy, Regional Studies, 40(6), 667-678. [ Links ]

Faludi, A. (2010). C ohesion, Coherence, Cooperation: European Spatial Planning Coming of Age? London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Farinós, J. (2015). Cohesión territorial / coesão territorial / territorial cohesion. In L. López Trigal (Dir.), J. A. R. Fernandes, E. S. Sposito, & D. T. Fighera (Coord.), Diccionario de Geografía aplicada y profesional: terminología de análisis, planificación y gestión del território (pp. 105-106). León: Universidad de León. [ Links ]

Ferrão, J. (2010). Ordenamento do território: 25 anos de aprendizagem? In Eurocid (Ed.), Europa Novas Fronteiras, Portugal – 25 anos de Integração Europeia. 26/27 (pp. 77-84). Parede: Princípia. [ Links ]

Figueiredo, A. F. (Coord.) (2010). Territorial Survey in Portugal. Lisboa: Instituto Financeiro para o Desenvolvimento Regional, IP. [ Links ]

Fyfe, N. R. (2009). Policing. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 8 (pp. 212-216). Conventry: Elsevier.

Gold, J. R. (2009). Behavioral Geography. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 6 (pp. 282-293). Conventry: Elsevier.

Goodwin, M. (2013). Regions, Territories and Relationality: Exploring the Regional Dimensions of Political Practice. Regional Studies, 47(8), 1181-1190. [ Links ]

Haggett, P. (2001). Geography. A global synthesis. London: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Hassler, M. (2009). Commodity Chains. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 2 (pp. 202-208). Conventry: Elsevier.

Howitt, E. (2009). Land Rights. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 5 (pp. 118-123). Conventry: Elsevier.

Leonardi, R. (2005). Cohesion Policy in the European Union - The Building of Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Luukkonen, J., & Moilanen, H. (2012). Territoriality in the Strategies and Practices of the Territorial Cohesion Policy of the European Union: Territorial Challenges in Implementing “Soft Planning”. European Planning Studies, 20(3), 481-500. [ Links ]

Martin, J., Rhys, J., & Michael E. (Eds.) (2004). An introduction to political geography. Space, place and politics. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2010). Old vs Recent Cross-Border Cooperation: Portugal-Spain and Sweden-Norway, AREA, 42(4): 434-443. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2011). (Re)defining the concept of Euroregion. European Planning Studies, 19(1), 141-158. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2013). Assessing territorial impacts of the EU Cohesion Policy: the Portuguese case. European Planning Studies, 22(9), 1960-1988. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2013b). Euro-Meso-Macro: The new regions in Iberian and European Space. Regional Studies, 47 (8), 249-1266. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2014a). The Europeanization of Spatial Planning processes in Portugal within the EU Cohesion policy Strategies (1989-2013). Geography and Spatial Planning Journal, 6, 201-222. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2014b). Assessing Territorial Impacts of the EU Cohesion Policy at the Regional Level: the Case of Algarve. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 32(3), 198-212. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2014c). Territorial Impact Assessment (TIA). The process, Methods and Techniques. Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Geográficos. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2014d). Territorial cohesion trends in Inner Scandinavia: the role of cross-border cooperation (INTERREG-A 1994-2010). Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift, 68(5), 310-317. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2016a). Territorial Cohesion: An European Concept. European Journal of Spatial Development, 60. www.nordregio.se/Global/EJSD/Refereed%20articles/refereed60.pdf [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2016b). EU Cohesion Policy in Spain. Regional Studies. Published online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1187719 [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2016c). EU Cohesion Policy in Sweden (1995-2003). A territorial Impact assessment . European Structural and Investment Funds journal, 3(4), 209-230. [ Links ]

Medeiros, E. (2016d). Territorial Impact Assessment and Cross-Border Cooperation. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 95-115. [ Links ]

Mendez, C. (2013). The Post-2013 Reform of the EU Cohesion Policy and the Place-Based narrative. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(5), 660-660. [ Links ]

Molle, W. (2007). European Cohesion Policy. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Moreno, L. (2002). Desenvolvimento Local em Meio Rural. Caminhos e Caminhantes. (Dissertação de Doutoramento). Disponível em: www.ceg.ulisboa.pt/wpcontent/uploads/2016/04/LMoreno_DesenvTerritRural07.pdf [ Links ]

Penrose, J. (2009). Nation. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 7 (pp. 223-228). Conventry: Elsevier.

Paasi, A. (1999). Boundaries as social practice: Territoriality in the world of flows. In D. Newman (Ed.) Boundaries, territories and postmodernity (pp. 69-88). London: Frank Cass. [ Links ]

Perkmann, M. (2003). Cross-border regions in Europe - Significance and drivers of regional cross-border co-operation. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(2), 153-171. [ Links ]

Perrin, T. (2010). Inter-territoriality as a new trend in cultural policy? The case of Euroregions. Cultural Trends, 19(1-2), 125-139. [ Links ]

Potluka, O. (2010). Impact of EU Cohesion Policy in Central Europe. Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Garcilazo, E. (2015). Quality of Government and the Returns of Investment: Examining the Impact of Cohesion Expenditure in European Regions. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1274-1290. [ Links ]

Sack, R. (1983). Human Territoriality: A Theory. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 73(1), 55-74. [ Links ]

Sassen, S. (2000). Territory and Territoriality in the Global Economy. International Sociology, 15(2), 372-393. [ Links ]

Storey, D. (2009). Political Geography. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 3 (pp. 243-253). Conventry: Elsevier.

Taylor, D. (2009). Belonging. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 1 (pp. 294-300). Conventry: Elsevier.

TA. (2007). Territorial Agenda of the European Union: Towards a More Competitive and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions, Agreed at the Occasion of the Informal Ministerial Meeting on Urban Development and Territorial Cohesion on 24/25 May, Leipzig, Federal Republic of Germany. Retrieved from: www.eu-territorial%20agenda.eu/Reference%20Documents/Territorial-Agenda-of%20the-European-Union-Agreed-on-25-May-2007.pdf [ Links ]

TA, 2020. (2011). Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020 - Towards an Inclusive, Smart and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions, Agreed at the Informal Ministerial Meeting of Ministers Responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development on 19th May, Hungary: Gödöllő. Retrieved from: www.euterritorialagenda.eu/Reference%20Documents/Territorial-Agenda-of-the-European-Union-Agreed-on-25-May-2007.pdf

López Trigal, L. (Ed.) (2015). Diccionario de Geografía Aplicada Y Prodesional. Terminología de análisis, planificación y gestión del território. León: Universidad de León. [ Links ]

Zaucha, J., Komornicki, T., Böhme, K., Świątek, D., & Żuber, P. (2014). Territorial Keys for Bringing Closer the Territorial Agenda of the EU and Europe 2020, European Planning Studies. 22(2), 246-267. [ Links ]

van der Wusten, H. (2009). Cox, K. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 2 (pp. 325-326). Conventry: Elsevier.

Warwick, E. (2009). Defensible Space. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 3 (pp. 31-38). Conventry: Elsevier.

Wastl-Walter, D. (2009). Borderlands. In N. Castree, M. Crang, & M. Domoah (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography Vol. 1 (pp. 332-339). Conventry: Elsevier.

Recebido: Janeiro 2016. Aceite: Outubro 2016.

NOTAS

iConference: The EU Cohesion Policy in Portugal – Contributions to the Territorial Development – 28‑01‑2013. iiAccessibility: transport accessibility, accessibility to energy networks and e‑connectivity.

![Os inquéritos [À fotografia e ao Território]: um retrato múltiplo do território português [do séc. XIX até ao presente]](/img/pt/next.gif)