Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.109 Lisboa dez. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis11806

COMENTÁRIO DE AUTOR

The aesthetics of ruins: failure, decay, planning and poverty

A estética das ruínas: fracasso, decadência, planeamento e pobreza

L'esthétique des ruines: échec, décadence, planification et pauvreté

João Sarmento1

1Professor Auxiliar, com Agregação, do Departamento de Geografia do Instituto de Ciências Sociais e Investigador do Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade da Universidade do Minho, Campus de Azurém, 4800-058, Guimarães, Portugal. E-mail: j.sarmento@geografia.uminho.pt

ABSTRACT

Ruins take many shapes and result from numerous and diverse human and non-human interactions. Acknowledging their place and arrangements, considering their spatial orderings, evaluating hierarchies, patterns and significations, and unravelling their ‘performance’, role, effect and marked absences, is key to a critical and significant engagement with the politics, grammars and productive power of materials that are in place. Ruins are material sites that animate new possibilities of living: they should be perceived as dynamic and relational, as interstitial, as sites of plurality, plasticity, dismantling and destabilizing the power of endless self-invention. Schönle’s (2006, p. 652) argument that ‘we cannot leave ruins alone and let them simply exist in their mute materiality’ guides the following four examples. While ruins pose challenges to planners and to politicians, constituting threats and opportunities, they speak to us of decadence, failure, loss, beauty, change and pleasure.

Keywords: Ruins; aesthetics; performance; possibilities.

RESUMO

As ruínas têm múltiplas formas e resultam de numerosas e diversas interações humanas e não-humanas. Reconhecer o seu lugar e aparência, considerar as suas configurações espaciais, avaliar hierarquias, padrões e significados, e desvendar seu 'desempenho', papel, efeito e ausências, é fundamental para uma articulação crítica e significativa com as políticas, gramáticas e poder produtivo das substâncias em jogo. As ruínas são locais materiais que animam novas possibilidades de vida: devem ser percebidas como dinâmicas e relacionais, como intersticiais, como locais de pluralidade, plasticidade, desmantelando e desestabilizando o poder infinito da auto-invenção. O argumento de Schönle (2006, p. 652) de que “não podemos deixar as ruínas em paz e deixá-las simplesmente existir na sua materialidade muda“ orienta os quatro exemplos seguintes. Enquanto as ruínas representam desafios para os planeadores e para os políticos, constituindo ameaças e oportunidades, elas apontam para a decadência, o fracasso, a perda, a beleza, a mudança e o prazer.

Palavras-chave: Ruínas; estética; performance; possibilidades.

RÉSUMÉ

Les ruines ont des formes multiples et résultent de nombreuses et diverses interactions humaines et non humaines. Reconnaître leur place et leur apparence, prendre en compte leurs configurations spatiales, évaluer les hiérarchies, les modèles et les significations, et découvrir leur “performance“, leur rôle, leurs effets et leurs absences est essentiel pour une articulation critique et significative avec les politiques, les grammaires et le pouvoir productif de substances en jeu. Les ruines sont des lieux matériels qui animent les nouvelles possibilités de la vie: elles doivent être perçues comme dynamiques et relationnelles, comme interstitielles, comme des lieux de pluralité, de plasticité, de démantèlement et de déstabilisation du pouvoir infini de l’invention de soi. L'argument de Schönle (2006, p. 652) selon lequel “nous ne pouvons pas laisser les ruines en paix et les laisser simplement exister dans leur matérialité muette“ guide les quatre exemples suivants. Alors que les ruines posent des défis aux planificateurs et aux politiciens, constituant des menaces et des opportunités, elles évoquent le délabrement, l’échec, la perte, la beauté, le changement et le plaisir.

Most clés: Ruines; esthétique; performance; possibilités.

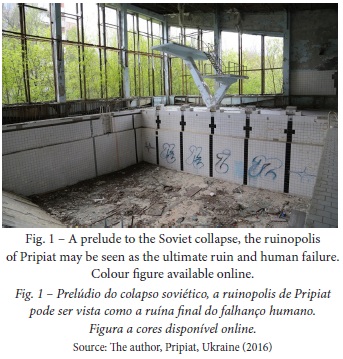

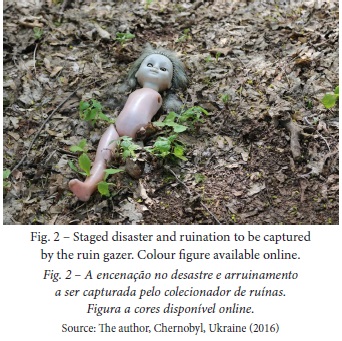

I. CHERNOBYL, UKRAINE: THE ULTIMATE RUIN?

Fast ruins may result from war, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, landslides among others. In Chernobyl, a nuclear catastrophe produced a landscape of disaster (fig. 1). Alexievich (2013) explains well how in the weeks and months immediately after the explosion people could not understand how the vast area (The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is roughly the size of Luxembourg) changed. All was apparently the same and there was little material change. Yet, an invisible and incomprehensible layer of radiation forced people to leave. The minute the explosion took place the clock was set in motion. Yet it was only after some years or even decades that we can gaze at the ruin. From a simultaneously fast and slow ruin a dark tourism destination emerged, and in 2016, over 10 000 tourists visited the area (fig. 2). Unquestionably, Chernobyl is one of those archetypal spectral places (Lee, 2017), which imperceptibly indicates the presence of something. But at the same time, and perhaps more intriguingly, the ruin slowly became a heaven for nature, a nature which cannot include humans for more than a few hours. Wolfs, deer, horses, fish, birds, forests and plants of all kinds thrive, although it is not clear still the magnitude of the disaster effects on them.

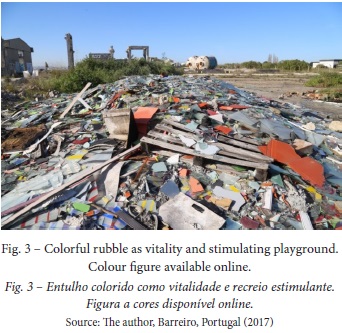

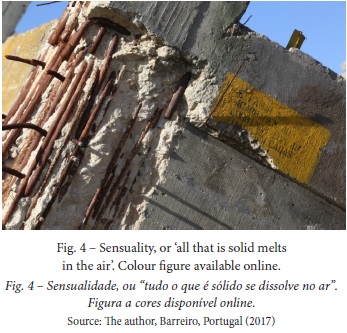

II. FROM INDUSTRIAL EMPIRE TO CONTAMINATED RUIN

CUF (Company Factory Union) moved to Barreiro in 1907. Producing oils, soap, sulfur, sulphuric acid, fertilizers, etc. this large company, at one time the largest industrial complex of Iberia, produced also a vast industrial landscape. From the mid-1970s, nationalisation, de-nationalisation and desindustrialisation left 214 hectares of brownfields which are now an enigma for local politicians, a sought after site for developers, and a paradise for ruingazers (fig. 3). Discourses of progress framed in neoliberal agendas envisage a gigantic development plan connected to Lisbon by a new bridge. For now the financial crisis postponed the mimicking of Lisbon’s late 1990s waterfront development on the left bank, and we can move in a transient and interstitial time and space. Here ruins ‘confound the normative spacing’s of things, practices and people’, and regulated bodies may escape urban restraints, and destabilize common aesthetics, foreground alternative aesthetics about where and how things should be situated, and transgress boundaries between outside and inside, and between human and non-human spaces (Edensor, 2005, p. 18). For a limited time we have the opportunity to promote the experience of post-industrial nostalgia (fig. 4).

III. UNPREDICTABLE PLANNING: ABANDONED SITES OR BUSINESS AS USUAL

The 1976 soil classification law, which governed Portuguese planning in the past 40 years, allowed for a disproportionate production of urban land. If the country has an excess of housing, building all that has been approved by Portuguese municipalities would lead to an even more unsustainable juncture. Allotment presupposes the construction of infrastructures in a predetermined period of time, but it does not imply the construction of what has been approved in any set of time. The result is that it is possible to have infrastructured allotments waiting development for an unspecified timei. Understanding land and housing as an asset and commodification, absorbing surplus capital, and fixing capital in space (Harvey, 1989), results in having finance capital dictating growth and tempos, while planners and citizens wait undeterminably. Regardless of looking at infrastructured sites as suspended projects or just as ‘business as usual’, the country is overflowing with empty or half empty projects. Some are totally vacant, others are partially completed and the odd house or apartment block exists on its own. They certainly bear a resemblance to Kitchin, O’Callaghan and Gleeson (2014) new ruins, and often their signature is the broken electricity box or lamp post, and the thriving urban wilderness (Jorgensen & Tylecote, 2007) covering idle sidewalks (figs. 5 and 6).

IV. CONCRETE SKELETON AS RUIN: THE GRANDE HOTEL OF BEIRA, MOZAMBIQUE.

Colonialism and tropical modernism imagined a Grande Hotel in Mozambique in the early 1940s. Advertised in the 1950s as the most luxurious hotel south of the Sahara, the unsustainable nature of the investment in Beira and an international changing environment led to closure in 1963. Parties, balls, swimming events, beauty contests and dinners continued, stretching routines and a sense of harmony for the elites. The hotel was built as the inversion of violence, a space of order and safety for romance, intimacy, sport, social gathering and business (Sarmento & Linehan, 2018). The after-life of the Hotel reveals an enduring decay, as the site hosted the military after independence and throughout civil war, and more recently a growing number of families. Between 2000-3000 residents live in poverty among an enormous skeleton of former luxury (fig. 7). Ruin porn, or the anesthetization of abandonment and decline has underlined the heroic qualities of the dilapidated building, masking the ways in which the ruin become enrolled into new networks, involving daily rhythms and routines and flexible and mobile ways of intersection (fig. 8). Ruins can, together with other material sites, inform us of the ‘distinctive historicity’ (Mbembe, 2001) of places, which are rooted in a multiplicity of times, trajectories, and rationalities that must be conceptualised and understood in relation to a globalised world.

Although the four examples might seem disconnected, for their nature and pathos is apparently so different, that is an illusion. Failure, decay, poverty and nostalgia are common features embedded in our daily landscapes. Whether ghost estates, abandoned hotels, old industrial landscapes, sites just pending redevelopment, ruins provide us graspable materials which support reflections upon our condition. Reflecting upon ruins help us to destabilize taken for granted assumptions. Official and appropriate uses may inform us of our inclination to label land, for example. Western culture has developed a clear fascination for ruins, and the last decades have witnessed an explosion of ruin-imagery in painting, photography, cinema, etc. The aesthetics of rubbish, of dissonances and disorder, of enchantment, disenchantment and re-enchantment, are simultaneously related to an attraction for pleasurable decay and to a fear for a dystopian dark side of humanity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research has been sponsored by Portuguese national funds through the Fundac¸a~o para a Cie^ncia e a Tecnologia (FCT), I.P. – the Portuguese national agency for science, research and technology – under the Project PTDC/ATP-EUR/ 1180/2014 (NoVOID - Ruins and vacant lands in the Portuguese cities: Exploring hidden life in urban derelicts and alternative planning proposals for the perforated city).

REFERENCES

Alexievich, S. (2013). Vozes de Chernobyl: história de um desastre nuclear [Voices from Chernobyl: the oral history of a nuclear disaster]. Amadora: Elsinore. [ Links ]

Jorgensen, A., & Tylecote, M. (2007). Ambivalent landscapes - wilderness in the urban interstices. Landscape Research, 32(4), 443-462. [ Links ]

Edensor, T. (2005). Industrial Ruins: Space Aesthetics and Materiality. Oxford: Berg. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (1989). The Condition of Post-Modernity. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Kitchin, R., O’ Callaghan, C., & Gleeson, J. (2014). The New Ruins of Ireland? Unfinished Estates in the Post-Celtic Tiger Era. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(3), 1069-1080.

Lee, C. (Ed.) (2017). Spectral Spaces and Hauntings: The Affects of Absence. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. (2001). On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Sarmento, J., & Linehan, D. (2018) The Colonial Hotel: spacing violence at the Grande Hotel, Beira, Mozambique. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. doi: 10.1177/0263775818800719 [ Links ]

Schönle, A. (2006) Ruins and history: Observations on Russian approaches to destruction and decay. Slavic Review, 65(4), 649-669. [ Links ]

NOTA

iWhile a new law has been in place since 2014 which significantly alters these processes, reverting the classification of urban soils carries numerous challenges and costs.