Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.110 Lisboa abr. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis17202

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Finisterra Annual Lecture: valuing place in a Chicago market

Lição Anual da Finisterra: valorizando o lugar num mercado de Chicago

Leçon Annuelle de Finisterra: valorisation du lieu dans un marché de Chicago

Lección Anual de Finisterra: valorando espacio en el mercado de Chicago

Tim Cresswell1

1 Dean of the Faculty and Vice President for Academic Affairs, Professor of American Studies Trinity College, CT 06106, Hartford, USA. Email: timothy.cresswell@trincoll.edu

ABSTRACT

This essay approaches the ideas of value and valuing though an exploration of the Maxwell Street market in Chicago, USA. The market was the largest open-air market in North America for much of the twentieth century. From the 1960s onwards it has been subjected to various forms of valuing and devaluing leading to its eventual demise in its historic location in 1994. The essay explores how the market and things in the market entered and left various regimes of value over time. The focus is on the role of hub-caps, home-made instruments called Stradizookys, and the process of tax-increment financing. The essay ends with some thought around order and regulation in the urban landscape.

Keywords: Value; valuing; Maxwell Street; market; Chicago; order; tax increment financing.

RESUMO

Este ensaio aborda as ideias de valor e valorização através de uma exploração do mercado de Maxwell Street em Chicago, EUA. Este foi o maior mercado ao ar livre na América do Norte durante grande parte do século XX. A partir dos anos 1960, foi submetido a várias formas de valorização e desvalorização, levando à sua eventual extinção na sua localização histórica em 1994. O ensaio explora como o mercado e as coisas no mercado entraram e deixaram vários regimes de valor ao longo do tempo. O foco está no papel das calotas (tampões para rodas de automóveis), instrumentos caseiros chamados Stradizookys e no processo de financiamento por incremento de impostos. O ensaio termina com algumas reflexões em torno da ordem e regulação na paisagem urbana.

Palavras-chave: Valor; valorização; Maxwell Street; mercado; Chicago; ordem; financiamento por incremento fiscal.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet essai aborde les idées de valeur et de valorisation à travers une exploration du marché de Maxwell Street à Chicago, États-Unis. Ceci était le plus grand marché de plein air en Amérique du Nord depuis une grande partie du XXe siècle. À partir des années 1960, il a été soumis à diverses formes de valorisation et de dévaluation conduisant à son éventuelle extinction dans son lieu historique en 1994. L'essai explore comment, au fil du temps, le marché et les choses dans le marché ont pénétré et laissé différents régimes de valeur. L'accent est mis sur le rôle des roues de pneus, sur les instruments de fabrication artisanale appelés Stradizookys, et sur le processus de financement des augmentations d'impôts. L'essai se termine par une réflexion sur l'ordre et la régulation dans le paysage urbain.

Mots-clés: Valeur; appréciation; Maxwell Street; marché; Chicago; ordre; financement d’augmentation des taxes.

RESUMEN

Este ensayo aborda las ideas del valor y valoración a través de una exploración del mercado Maxwell Street en Chicago, USA. Este fue el Mercado al aire libre más grande en Norteamérica, durante gran parte del siglo XX. Desde la década de 1960 en adelante, ha sido sometido a varias formas de valoración y devaluación que llevaron a su eventual desaparición en su localización histórica en 1994. Este ensayo explora cómo el mercado y objetos del mismo ingresaron y dejaron varios regímenes de valor con el pasar del tiempo. La atención se centra en el papel de los tapacubos, en los instrumentos caseros llamados Stradizzokys, y en el proceso de financiamiento por incremento de impuestos. El ensayo termina con algunos pensamientos relacionados con el orden y regulación del paisaje urbano.

Palabra clave: Valor; valoración; Maxwell Street; mercado; Chicago; orden; financiamiento por incremento de impuestos.

I. INTRODUCTION

Places are made from things: things and practices and meanings (Cresswell, 2014). In the language of phenomenology places gather (Casey, 1996). In the terms of assemblage theory they assemble (DeLanda, 2006; Dovey, 2010). Whatever the theoretical language, one way into place is through the things that gather there. Places are also sites of value. Forms of valuing (and devaluing) help to distinguish a rich sense of place from mere location. The place I focus on here is the area around the Maxwell Street Market in the near west side of Chicago. This talk is part of a wider project exploring a hundred years of this market and the area around it through various practices of valuing including writing, photographing, archiving and planning. The project is, simultaneously, about the things of Maxwell Street and the practices that value and devalue those things. The concerns of this talk thus reflect those of the wider project.

Maxwell Street Market was the largest open-air market in North American for much of the last century. Jewish street pedlars started it in the 1880s and by the middle of the twentieth century it was largely associated with the African American population and the development of the Chicago blues. In the last two decades of the twentieth century it was gradually erased by gentrification processes led by the University of Illinois at Chicago (Berkow, 1977; Grove, 2002; Cresswell & Hoskins, 2008; Cresswell, 2012). Throughout its history the market and the area around it was a site of heterogeneous gathering and assemblage of things, practices and stories. Here I provide just a sliver of this place through what, on the face of it, are highly disparate stories. The first half of this talk focuses on two objects as they appear in a variety of archives – hubcaps and DIY musical instruments called stradizookys. The second half of the essay widens the scope of investigation and considers the role of value in the process of declaring the area a Tax Increment Financing district in 1999 and ends with a reflection on aesthetic and notions of order.

First, though, a word on value. Exploring a market place means returning to one of the root meanings of the city – a place where exchange happens (Weber, 1960; Jacobs, 1969). From the writings of Max Weber to the heretical theory of urban origins proposed by Jane Jacobs to contemporary work in the Marxist political economy tradition the city is a site characterised by, even originating in, the creation of surplus value through trade. Exploring a market as a place, then, means exploring the most urban of urban sites. Consider the words of the sociologist Louis Wirth from his classic book The Ghetto.

“The noises of crowing roosters and geese, the cooing of pigeons, the barking of dogs, the twittering of canary birds, the smell of garlic and of cheeses, the aroma of onions, apples, and oranges, and the shouts and curses of sellers and buyers fill the air. Anything can be bought and sold on Maxwell Street. On one stand, piled high, are odd sizes of shoes long out of style; on another are copper kettles for brewing beer; on a third are second-hand pants; and one merchant even sells odd, broken pieces of spectacles, watches, and jewelry, together with pocket knives and household tools salvaged from the collections of junk peddlers. Everything has value on Maxwell Street, but the price is not fixed. It is the fixing of the price around which turns the whole plot of the drama enacted daily at the perpetual bazaar of Maxwell Street.” (Louis Wirth, 1928, p. 232-233).

The processes of valuing and exchange at Maxwell Street were heterogeneous and multi-scalar. The Maxwell Street Market was (and still is – in a relocated form) a flea market. It was a place where a significant portion of what was for sale was second hand. Shoppers came to the market in large numbers expecting to get bargains. At the same time, the stallholders expected to, in a telling term “cheat you fair”. The process that ensued was bargaining. This was a practice of valuing that led to (in some instances) the continuing biography of an object as it moved from Maxwell Street to the domestic spaces of shoppers from across Chicagoland.

Towards the end of its life – in the last three decades of the twentieth century – Maxwell Street was the site of heated debates about the gentrification process that was gathering pace and would eventually lead to the demise of the market. Many of the arguments that swirled around Maxwell Street were arguments about the values of things. Briefly put, discussion centred on whether certain objects in the Maxwell Street area, and the area itself deserved to persist or be discarded. The idea of “regimes of value”, derived from the work of Appadurai, suggests certain contexts in which things are ascribed value (Appadurai, 1986; Jamieson, 1999; Schlosser, 2013). It performs a critique of the idea of inherent value at the same time as it dispenses with the differentiation between commodity value and gift value (as two subsets of exchange value). Things travel through these regimes and in doing so have “careers” or “biographies” (Kopytoff, 1986). In Appadurai’s terms, they have “social lives” (Appadurai, 1986). In this sense the objects of Maxwell Street, and Maxwell Street itself, are fluid concretisations of the relations between the human and the non-human worlds – of the way values is ascribed to objects.

In the end Maxwell Street became the site of a protracted decade long struggle over valuing as the University of Illinois Chicago bought up the land and transformed it into an expensive “university village” built along trendy new-urbanism principles. More recently the area has been declared a Tax Increment Financing District so that private developers can use as yet unrealised taxes to fund the development of the area for 22 years. In order for this place to be classified in this way it has to be declared essentially valueless – as decrepit and run-down and in need of renewal. As we shall see, the process of Tax Increment Financing is essentially a magical process of diagnosing valuelessness in the landscape and then making that valuelessness valuable. It is a way of inserting the micro-geographies of a run-down landscape into the macro-geographies of the global financial system.

To value something is to include it in some way in a world of significance. To value something is to decide it is worthy of inclusion in a sphere that is itself deemed worthy. Valuing is an act of inclusion and exclusion. I am thinking here of value as a verb more than a noun: less the idea of the worth in things and more the idea of making things worthy. With this in mind let us proceed to some of the things that were valued as they entered and left Maxwell Street.

II. HUB CAPS

In 1974, a reporter discovered 72 year-old Leamon Reynolds next to a six-foot high pile of hubcaps selling for around $1.50. Reynolds, it turns out, “can find you a 1952 Ford hubcap in five seconds, thanks to his secret filing system. Where does Reynolds get his fantastic stock? From state road workers, he says, they pick them up while patrolling expressways” (Star, 1974, p. 154).

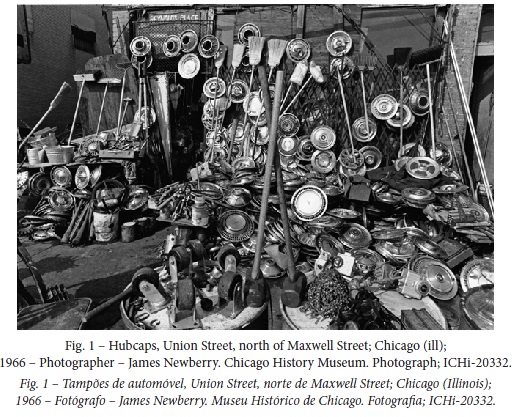

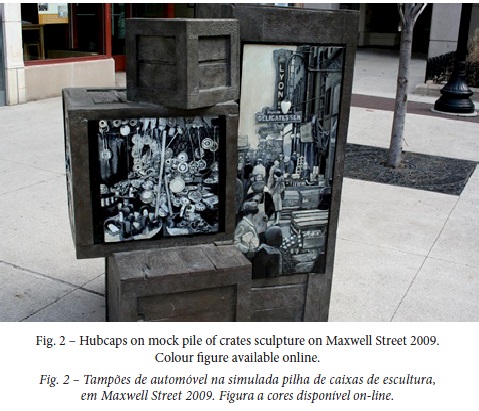

Six years earlier, Reynolds’ hubcap stand had attracted the attention of the photographer, James Newberry, who was entranced enough with its silvery stock to take a picture that can be found today in the archives of the Chicago History Museum (fig. 1). The picture can also be seen on the remaining block of Maxwell Street, on the side of one of the mock-piles of boxes which remind the present-day visitor of the place this once was (fig. 2). In this way the humble hubcap found its way first into the official archive of the market and then back, in simulated form, onto the street where the market once was.

Newberry’s image of hubcaps and brooms is like a still life. There are no people. Many of the photographs of Maxwell Street in the archive are of intense crowds of peoples and varieties of performance that take place in a market. This, on the other hand, appears as an accidental arrangement of confused forms and surfaces. The beauty of the photograph lies in the configuration of the hubcaps as discs and the straight lines of the brooms. It presents us with aesthetically pleasing confusion.

Photography is one way in which hubcaps in Maxwell Street entered regimes of value. But there are other ways. The hubcap appears repeatedly in the words of those who argued for the demolition and relocation of the market. Its banal materiality became a vehicle for a discourse that framed the market as a site of dubious moral order. In the archive of the University of Illinois at Chicago are a series of letters written to Mayor Richard J Daly’s office supporting the relocation of the market. One, from Michael Shea of “Buy a Tux” Formal Wear Superstore on nearby West Roosevelt Avenue reads:

“Where do the goods come from? On more than one occasion we bought my own hubcaps on Maxwell Street (15 minutes after they were stolen off our car). The absence of this can only have a positive effect on the area and Chicago proper.”i

The hubcap was linked to much more serious pronouncements of moral dissolution in a letter from the University’s head gymnastics coach on the 3rd of November 1993.

When I think of Maxwell Street I think of 3 things:

1.Garbage;

2. Crime;

3. Perversion;

…

“In regard to crime I personally have witnessed drug deals, prostitution, car thefts, and creeps prowling the area daily. I have to buy back my own hubcaps, radio and accessories two or three times a year.”ii

The story of finding your own hubcaps at Maxwell Street just after they have been stolen is one of the most often-told stories of Maxwell Street. It is told so often that, in most cases, it is unlikely to be true. Who, after all, knows what their own hubcaps look like? This is the way a place becomes storied. A story is told over and over until it sticks – until it becomes so much common sense.

Hubcaps clearly exerted an influence on Maxwell Street. To photographers such as James Newberry they presented an aesthetic opportunity. Piled up in profusion they created form and contrast – they became a sign of the object richness of the market. They were beautiful. To others, less enamoured of the market, they represented an amoral place in which hubcaps were signs of a wider broken society – linked to crime and perversion.

III. STRADIZOOKY

In the archives of the writer Ira Berkow there are the transcripts of all the oral histories that he collected for his book Maxwell Street – an account collated from oral histories of those who lived and worked there over the years (Berkow, 1977). Included in the archives are some transcripts which never made it into the final manuscript. These include an interview with Tyner White – an interview that hilariously goes nowhere:

“IB What does the street mean to you? What does Maxwell Street mean to you?TW What Maxwell Street means to me? Essentially, it’s something that the city means. The city means an exchange market. You visit there, and you offer others things you don’t need, and you get things from them that they don’t need. These are wares. Wares are things which were. And now I don’t need it anymore.”iii

In the home of the economics professor, Steve Balkin, an advocate for the market, I noticed some curious wooden objects hanging from shelves. These, he told me, are “Stradizookys” – musical instruments made from scrap bits of wood and other junk. Tyner White made them. The word Stradizooky is derived from Stradivarius, the renowned violinmaker and Suzuki, the originator of the Suzuki method of teaching children to play violin. The Stradizooky combines a passion for recycling wood with a quest for racial/ethnic togetherness. One example in Balkin’s loft has “Blacks + Jews = Blues” inscribed upon it. Tyner White graduated from the Masters of Fine Arts programme in creative writing at the University of Iowa. After a flirtation with poetry he dedicated himself to educating people about the wonders of wood and the necessity of creative recycling. Like many before him he gleaned stuff from the Maxwell Street area to work on his new inventions. A journalist from the Chicago Reader was impressed with his creativity.

“He's built a mad hatter's assortment of prototypes: a possibly functional tape dispenser in the shape of a cat, rubber-tipped walking sticks with handles of telephone wire, oversize sculptural chess pieces sporting shiny metal screws for arms, a deeply discordant toy violin. "Here," he says, offering a box of lumber scraps that he's sanded and bevelled. "Take a diamond."” (Isaacs, 2005).

Tyner White was a central figure in the “Maxworks” artists collective who inhabited 716 Maxwell Street until they were forcefully evicted to make way for the “University Village” in March 2002. Theirs was the last inhabited building on the old street. Once evicted White took his gleaning project to the “Resource Centre” where he founded the “Maxwood Institute of Treecenomics” which sits alongside the “Creative Reuse Warehouse” - a place where artists can get scrap materials cheaply for the construction of installations and other artworks.

On New Year’s Eve at the turn of the millennium an old Nabisco factory at 720-724 West Maxwell Street mysteriously went up in flames. Tyner White and the residents of the Maxworks collective witnessed the fire. White recounted his experience to a journalist from the Chicago Reader.

“It's like a war and they're trying to exterminate our resources," says White, who has built thousands of bizarre instruments and knickknacks out of "recycled" scrap wood, including the "Stradizooky," a violin-like musical instrument, and his trademark "Toker," a device for smoking marijuana that he claims will help replace the demand for cigarettes. He says he now hopes to "get a moratorium on bulldozing" and to pave Maxwell Street with bricks salvaged from the demolished factory, which, he says, had also contained remnants from the days when the market was predominantly populated by central European Jews.” (Lyderson, 2000).

When I visited the relocated Maxwell Street Market on its hundredth birthday, there was Tyner White, playing away on a stradizooky as the Maxwell Street Blues Band did its thing.

The stradizooky, like the hubcap, is valued in particular ways that are connected to the place it is associated with – Maxwell Street. It tells is about Tyner White’s valuation of things that others consider to be junk and evidence for the decay of the Maxwell Street area. A piece of wood becomes a “diamond” or a musical instrument. This particular form of valuation is most evident in another of White’s appearances in the distributed archive. He turns up in a City of Chicago Community Development Commission Meeting Report for a Meeting held on 26th October 1993 to consider the future of the market. He points out that the University of Illinois at Chicago had a terrible recycling record and offers to take on some of the work at the Maxworks Institute (still on Maxwell Street at the time).

“We could convert some of the scrap lumber into workroom shelves and other kinds of things for the physical plant.And I would like to mention that in our block are several shuttered buildings which the University acquired over the years, in which they have manifested a wish to tear down.

Now the reason is that ten years from now, it would then be possible to install a four or ten or forty-six million research building.

…

I would recommend that the University consider recycling the warehouse buildings on Maxwell Street, make them available for use in a joint venture and find out how much this University can contribute to solving the recycling crisis.”iv

White’s advice was ignored.

IV. TAX INCREMENT FINANCING

In the case of hubcaps and the stradizooky we have seen how things, at a micro-geographic scale, enter and leave regimes of value in a particular geographic context – that of Maxwell Street. They are ingredients in the gathering of things that was Maxwell Street. In the remainder of this essay I focus on one particular process that Maxwell Street as a whole entered into. We have seen how both hubcaps and the stradizooky entered into debates about the value of Maxwell Street as a whole. Such things, as signs of decay and blight, also played a role in a macro-geographic process of valuing and devaluing called Tax Increment Financing.

The fluid restless nature of capital constantly comes up against the friction of fixed capital – the relative intransigence of bricks and mortar (Harvey, 1982). One way to navigate this problem and reduce the friction is to create financial instruments that bundle and abstract the idea of ‘place value’ and make it transferable. It is this process I want to explore now through another set of (de)valuing practices that were applied to the area around Maxwell Street Market in the late 1990s.

In 1999, the City of Chicago decided to designate the area around Maxwell Street as the Roosevelt/Union Redevelopment Project Area under the Tax Increment Finance Program. Tax Increment Financing (TIF) works by allocating as yet unrealized increases in property taxes from areas which are approved as TIF zones to pay for ‘improvements’ in that area. It had become possible to raise money in this way through an Illinois State law in 1977 but the first Chicago TIF district – the Central Loop – had not come into existence until 1984. Since then, the City of Chicago has used TIF financing in over 100 areas of the city and has been its most enthusiastic advocate (McGreal, Berry, Lloyd, & McCarthy, 2002; Gibson, 2003; Weber, 2010).

This is how TIF works. The first step is to designate a neighbourhood as ‘blighted’ – as devalued or relatively valueless. Once the designation of a blighted area has taken place an amount is allocated as the tax baseline based on tax revenues at the point of designation. This is then frozen and, in the following 23 years, there is no additional revenue from this tax base available for local school districts, roads, parks or any other general civic amenity. Any additional tax revenues that are then collected in subsequent years are used to finance various forms of development until the TIF district definition comes to an end after a 23-year period. Private developers can begin work based on future tax revenues. This process favours big developments on large parcels of land where large increases in tax revenue can be quickly realized. As with the Urban Renewal programmes of the 1960s, the TIF process uses eminent domain to purchase land. Unlike Urban Renewal the proceeds almost always flow directly to private property developers with very little transparency or public oversight. Many argue that this diverts money away from public bodies that would have benefitted from increasing tax revenues had TIF not been implemented.

Once the TIF district is dissolved the City benefits from the increased tax base which results from the development process. The idea is that as blighted properties are improved through the investment of TIF dollars then their value will increase along with the newly generated revenue. The difference between the tax base line and the new more valuable property is captured and reinvested for improvements thus further increasing the values.

Obviously there is a catch here as the increased tax revenues are not available in advance. The local state therefore has to invent a financial instrument to provide funds up front. To do this it issues bonds with future tax revenues as security. The bonds are sold through negotiated sales to a variety of investors including pension funds across the world. This puts the landscape into a complicated and fragile network of risk that is spread across a vast and unstable system. The landscape is enrolled into a topology of risk that it was previously outside of. The City government cannot assure the increase in tax revenues that the investment is based on – the main drivers of property value are also situated well beyond the TIF zone or even the City of Chicago.

The Roosevelt/Union area surrounding Maxwell Street was made a TIF district on May 21st 1999 and will cease to be one on May 21st 2022. At the time of its inception it was one of around 70 TIF districts, most of which had been approved in the two years immediately preceding it. As with all TIF zones the Roosevelt-Union area underwent an eligibility study in order to ensure that the district counted as ‘blighted’. The study was hired out to a consultant – Louik Schneider and Associates, Inc – who then submitted an eligibility plan to the City of Chicago’s Community Development Commission. Eventually the City Council approved the designation and the 58 acres of Roosevelt Union were given a 1997 taxable property value of $31 987.742.

The Roosevelt-Union Redevelopment Plan and Project report was published in October 1998. The objective of the Plan, it stated, was to “encourage mixed-use development, including new residential, institutional and commercial development within the Area” as well as enhance the city’s tax base and preserve the values of existing property. It stated that the area was well suited to mixed use due to the close proximity of transport infrastructure including the CTA bus and train lines and major highways (Chicago, 1998).

These general details are interspersed with ‘design objectives’ for the improved area including a “high standards of appearance” and the need to encourage:

“(…) a variety of streetscape amenities which include such items as sidewalk planters, flower boxes, plazas, variety of tree species and wrought-iron fences where appropriate (…).” (Chicago, 1998, p. 9).

At first glance, such details seem more than a little strange. Given the scale of investment in a TIF district and the context of global finance, details like flower boxes and wrought-iron fences appear very marginal. They are, however, central to the process of redevelopment of which TIF forms a part. Chicago has a long history of mixing aesthetics with urban planning, most famously, perhaps, in the “city beautiful” movement associated with the influential urban planner and architect Daniel Burnham, who insisted on the importance of grand and beautiful buildings to the well-being and morale of the populace.

“Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that our sons and grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty. Daniel Burnham.”v

In his 1909 plan for Chicago, Burnham sought to reconfigure the city through the construction of parks, boulevards, and grand, beautiful public buildings inspired by Haussmann’s renovation of Paris. Burnham believed that the aesthetics of this new city would uplift the masses. It was, as Peter Hall, has described it, “trickle-down urban development.”vi It was also trickle-down aesthetics. The ideology behind it was that the beauty of parks and museums would benefit everybody.

At the end of the twentieth century the role of aesthetics in urban development in Chicago had moved from the macro-aesthetics of “big plans” to the micro-aesthetics of wrought-iron fences and planters. Mayor Richard M. Daley had visited Europe in the mid-1990s and appreciated details of landscaping like decorative fencing, urban trees, and flower boxes. Daley decided that this was what Chicago needed to save it from becoming just another declining Rust Belt city. He started by getting the city government to beautify city properties, streets, and parks with faux wrought-iron fences and plantings and then, in 1999, pushed through a City Landscaping Ordinance that required private businesses to spend their own money on such measures. Daley clearly shared Burnham’s belief in the importance of beauty to urban life, but he sought to imprint his aesthetic vision on the city through a multitude of small plans.

The move toward small, incremental, additions to the city reflects the move from the grand modernist ambitions of urban renewal in the 1960s to the more piecemeal approach of TIF funding in the 1990s. The two are connected through the insertion into TIF agreements such as the one that includes Maxwell Street of a few lines specifying “planters, flower boxes, plazas, variety of tree species and wrought-iron fences where appropriate.”

V. REGULATION/ORDER

The addition of wrought iron fences for part of a long history of attempts to straighten out the market that combine aesthetics with regulation. The aesthetics of Maxwell Street were a constant source of contestation.

As early as the 1890s Chicago had attempted to erase the name Maxwell Street and replace it with West 13th Place. A strictly ordered street numbering system was preferred to the random names of an earlier time. Maxwell Street was to become part of the grid. Nobody paid attention.

In 1939 the Maxwell Street Merchants Association planned to modernize the market by insisting on a uniform size for street stalls and forbidding the shops along the street from using the sidewalk. Vendors’ carts were to be painted orange and blue and covered with sanitary canvas coverings, with a garbage receptacle attached. The plans were greeted in the press by a litany of references to the olfactory chaos of the market.

“Its architectural ears will be scoured and its appearance and olfactory tempo vastly improved.” (Chicago Daily News, 1939, p. 17).

“Smells? The modernizers look to a later day to begin the refining process on the Maxwellian potpourri. Later, too, they will essay revision of the street’s cacophonous symphony of screeching wheels, barking dogs, wheedling voices, blaring radios and cackling, crowing and honking fowl.” (Steyskal, Chicago Tribune, p. 1).

Sound and smell signify the excessive. Like the market, they overspill boundaries, transgressing the limits of the proper. They have to be controlled or removed through the logic of planning.vii

The plans for visual and olfactory uniformity were accompanied by a “code of conduct” that included the article “Maxwell Street no longer will condemn interventions, modernization and beautification without a careful examination” (Chicago Tribune, 1939). If the idea caught on, it was only for a short time. There are no images of Maxwell Street with uniform carts in the Chicago History Museum archives.

In 1966 the city’s Department of Urban Renewal included ideas for a new Maxwell Street Market in its proposals for the Roosevelt-Halsted area. The report reorganized the market as a special kind of place.

“The Maxwell Street Market is composed of business retail facilities in permanent structures and of merchants occupying sidewalk structures or temporary facilities erected for the weekend trade. This varied method of merchandising, plus the varied type of new and older merchandise offered has resulted in a unique market atmosphere. Such a market has developed in several of the central cities of the world’s major metropolitan areas and has proved not only an excellent retail outlet, but a boon to the tourist trade as well. An opportunity for development of such a market in a new physical setting would prove an asset to the merchant, and to the customers seeking not only unusual merchandise, but the convivial atmosphere of the true open-air market.” (Chicago Department of Urban Renewal).viii

The “convivial atmosphere of the true open-air market” was clearly appealing to the writers of this report. They wanted it and yet did not want it. The sound, smell, and appearance of the market, the very things that had made the street such a rich place to other writers and photographers over decades, needed taming. Everything in its proper place.

“It is anticipated that the existing Maxwell Street open air market can be accommodated on the privately owned open areas related to this shopping center. The combination of permanent structures, plus temporary market facilities. . . would result in the provision of a colorful, festive atmosphere conducive to creating and retaining shopping potential.” (Chicago Department of Urban Renewal).ix

The proposals again stressed a need for uniformity, for everything “from sign lettering, to plaza pavement, to brick color and texture. . . to be utilized in harmonious and restrained manner.” Again and again, planners and report-writers applaud the atmosphere of the market, then argue for ways to make this atmosphere more palatable, more “harmonious and restrained”—terms not often used to refer to the existing market. An ordered aesthetic based on standardized landscape features was consistently recommended.

In a 1966 visualization of a reformed Maxwell Street Shopping Center, stalls appear in neat, even rows within a contained courtyard, which is in turn surrounded by neat lines of evenly spaced trees. Trees, generally absent from images of Maxwell Street up to the 1980s, appear frequently in visions of the area’s future.

The assemblage of sights, sounds, and smells that characterized Maxwell Street Market throughout most of the twentieth century was, in some ways, organic. The market became part of the city in a more or less spontaneous way and maintained a more or less spontaneous form of order. The various schemes to order its excess sought to locate the market in a wider world of legibility imposed from outside. The abolition of smell, creation of uniform carts, and translation of the market into a “shopping center” were all part of this process.

Ordering Maxwell Street aesthetically was accompanied by a number of other forms of ordering. Up to the present day there have continually been questions about appropriate fees for stall-holders, payment of taxes, and standardization of measures and prices. Through most of Maxwell Street’s history, all of these were negotiable. The market has its own mÄtis, or practical knowledge. This was knowledge you learned in place through practice—the best ways to “cheat you fair.” Consider the arts of the market “puller” described by Louis Wirth

“The “puller” is a specialist. He has developed a fine technique of blocking the way of passers-by. Before he is aware of it, the unwitting and unsuspecting customer is trying on a suit that is many sizes too large and of a vintage of a decade ago. The seller swears by all that is holy that it fits like a glove, that it is the latest model put out by Hart Schaffner & Marx, and that he needs money so badly that he is willing to sell it at a loss of ten dollars. If the customer is skeptical and is inclined to ask how the dealer can stay in business and lose ten dollars on a suit, he is told confidentially, “You see, we sell so many of ’em.”On the sidewalk a puller shouts, “Caps, fifty cents!” In a moment he has a victim by the arm, and the salesman is trying on caps. “Yes, they are fifty cents apiece.” He finds one that fits. “Seventy-five cents for that one.”

“But I thought you said they were fifty cents?”

“Yes, but this one fits you!” (Louis Wirth, 1928, p. 233-234).

This conforms to the kind of practical local knowledge that James C Scott has called Metis.

“Any experienced practitioner of a skill or craft will develop a large repertoire of moves, visual judgments, a sense of touch, or a discriminating gestalt for assessing the work as well as a range of accurate intuitions born of experience that defy being communicated apart from practice.” (James C. Scott, 1998, p. 329).

The knowledge from the outside—the ordered and sweet-smelling aesthetics—corresponds to what Scott calls techne—systematic, abstract, often quantified and generalizable forms of knowledge. This is the knowledge of carefully measured carts, standardized fees, and externally imposed codified rules. MÄtis is local, techne is (or, more accurately, tries to be) universal.

The process of designating Maxwell Street as a TIF district was partly an aesthetic process that continued a long history of attempts at ordering and beautification.

In order to be considered ‘blighted’ an area had to have five or more ‘factors’ that, combined, would make the area “detrimental to the public safety, health, morals, or welfare” (Chicago, 1998, p. 10). It also had to be the case the area would have little chance of being ‘developed’ without action from the City. The list of factors that contribute to blight is given as:

“Age; dilapidation; obsolescence; deterioration; illegal use of individual structures; presence of structures below minimum code standards; excessive vacancies; overcrowding of structures and community facilities; lack of ventilation, light or sanitary facilities; inadequate utilities; excessive land coverage; deleterious land use of layout; depreciation of physical maintenance; or lack of community planning (…).” (Chicago, 1998, p. 10).

Nine of these were discovered in the area including, to a major extent, age, dilapidation, deterioration, excessive vacancies, excessive land coverage, and depreciation of physical maintenance. Each of these is then defined and mapped. The definition of ‘age’ as a factor in blight reads.

“Age presumes the existence of problems or limiting conditions resulting from normal and continuous use of structures which are at least thirty-five (35) years old. In the Redevelopment Project Area, age is present to a major extent in sixty-seven (67) of the seventy-three (73) (ninety-one and seven-tenths per cent (91.7%)) buildings and in thirteen (13) of the sixteen (16) (eighty-one and three-tenths per cent (81.3%)) blocks in the Redevelopment Project Area.” (Chicago, 1998, p. 12).

The report concludes that the re-development of the area will cost $103 000.000 A base line EAV was set at $3 968.563 with an expected EAV for 2008 of 48 000.000 to 55 000.000.

VI. CONCLUSION

Maxwell Street in the 1980s was the kind of place described in the following terms.

“During the week, the dusty vacant lots are more desolate than ever. Shabbily dressed old men sit silently on crumbling stoops and drink wine in garbage-strewn alleys; the few remaining buildings sag wearily, burned out stairwells and boarded-up windows telling the perennial urban story of neglect and decay. (‘The Sunday morning market may be in danger, but thanks to a new generation of bluesmen the music is as strong as ever’.” (Whiteis, 1988, p. 8).

And then consider Maxwell Street now. The remaining two blocks feature a pastiche of facades saved from demolition and used to provide the fronts for shops restaurants and a parking lot. It is part of an area described as University Village – a prestigious area of mid-high end town houses and apartments built on neo-traditional town planning principles. A pamphlet mailed to employees of the nearby University of Illinois, Chicago in 2001 advertised the area in the following way.

“Yesterday’s Heritage. Tomorrow’s Treasure”Chicago’s newest, most convenient, most thoughtfully planned neighborhood…a great life in the city.

University Village presents traditional Chicago style architecture on tree-lined streets

Townhome exteriors feature varying rooflines.

The site plan features neighborhood parks and green space corridors.

“Chicago’s next great neighborhood”

The stories of value recounted above describe moments in this transformation. They reveal how it is necessary to connect the materiality of place (by which I mean, in this instance, things like hub-caps, wood and wrought iron fencing), to meanings and narratives of place (such as the designation of ‘blight’). The combination of things and value and the regimes that authorize these combinations are key to deciding whether a place fades or endures.

Discussions of hub-caps, scrap wood and a host of other ‘things’ in and around Maxwell Street form part of a wider evaluation of the place that was Maxwell Street. Similarly, the act of defining an area through maps and statistics during the TIF process forms part of the quasi-scientific process of devaluing an area that is a necessary precursor to the revaluing process. The designation of “age” to property contributes to a definition of obsolescence – the notion that something is no longer of the times – is out of date. This designation ties a narrative of lack of value into the material landscape in order to legitimate certain practices of demolition and redevelopment that suit the purposes of private capital. Narrative becomes part of the landscape. This place with its hubcaps and scraps of wood (among many other objects) is defined as decrepit, decayed and obsolete. This lack of value – or negative value – is then repackaged as a new form of value that can produce a new kind of place. One without the Maxwell Street Market.

REFERENCES

Appadurai, A. (1986). Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value. In A. Appadurai (Ed), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (pp. 3-63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Berkow, I. (1977). Maxwell Street: Survival in a Bazaar. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

Casey, E. (1996). How to Get from Space to Place in a Fairly Short Stretch of Time. In S. Feld & K. Baso (Eds), Senses of Place (pp. 14-51). Santa Fe: School of American Research. [ Links ]

City of Chicago. (1998). Roosevelt-Union Redevelopment Plan and Project. In Chicago Co (Ed). Chicago: City of Chicago. [ Links ]

Chicago Daily News. (1939, May). Maxwell Street to Have Face Lifted, Ears Scoured. Chicago Daily News, 24, 17. [ Links ]

Chicago Tribune. (1939, June). Maxwell St, to Sell Ethics by the Dozen. Chicago Tribune, 25. [ Links ]

Cresswell, T. (2014). Place. In R. Lee, N. Castree, R. Kitchin, V. Lawson, A. Paasi, C. Philo, S. Radcliffe, S. M. Roberts & C. Withers (Eds), The Sage Handbook of Human Geography (pp. 7-25). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Cresswell, T. (2012). Value, Gleaning and the Archive at Maxwell Street, Chicago. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 37, 164-176. [ Links ]

Cresswell, T., & Hoskins, G. (2008). Place, Persistence and Practice: Evaluating Historical Significance at Angel Island, San Francisco and Maxwell Street, Chicago. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 98, 392-413. [ Links ]

DeLanda, M. (2006). A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London, New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Dovey, K. (2010). Becoming Places: Urbanism/Architecture/Identity/Power. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gibson, D. (2003). Neighborhood Characteristics and the Targeting of Tax Increment Financing in Chicago. Journal of Urban Economics, 54, 309-327. [ Links ]

Grove, L. (2002). Chicago's Maxwell Street. Chicago, IL: Aracadia Pub.

Isaacs, D. (2005, April). The Collected and the Ultimate Collector; Tyner White's Glorious, Homeless Hoard’. Retrieved from http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/the-collected-and-the-ultimate-collector-tyner-whites-glorious-homeless-hoard/Content?oid=918451

Jacobs, J. (1969). The Economy of Cities. New York: Random House [ Links ]

Jamieson, M. (1999). The Place of Counterfeits in Regimes of Value: An Anthropological Approach. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 5, 1-11. [ Links ]

Kopytoff, I. (1986). The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process. In A. Appadurai (Ed), The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (pp. 64-94). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Leyshon, A., & Thrift, N. (2007). The Capitalization of Almost Everything - the Future of Finance and Capitalism. Theory Culture & Society, 24, 97-115. [ Links ]

Lyderson, K. (2000, January). Burnt Out. Will the New Year's Eve fire break the spirit of preservationists fighting to save what's left of Maxwell Street? Chicago Reader. Retrived from http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/burnt-out/Content?oid=901112 [ Links ]

McGreal, S., Berry, J., Lloyd, G., & McCarthy, J. (2002). Tax-Based Mechanisms in Urban Regeneration: Dublin and Chicago Models. Urban Studies, 39, 1819-1831. [ Links ]

Motley, W. (1947). Knock on Any Door. New York, London: D. Appleton-Century company. [ Links ]

Schlosser, K. (2013). Regimes of Ethical Value? Landscape, Race and Representation in the Canadian Diamond Industry. Antipode, 45, 161-179. [ Links ]

Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Have, CT: Yale University Press.

Schwartz, C. (1999). Chicago Tif Encyclopedia. Chicago: Neighborhood Capital Budget Group. [ Links ]

Star, J. (1974). Maxwell Street Lives. Chicago Tribune Magazine. Chicago, 1. [ Links ]

Steyskal, I. (1939). The Old Order Changeth, Even on Maxwell Street. Chicago Sunday Tribune, August 27, 1, 1.

Weber, M. (1960). The City. Germany: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Weber, R. (2010). Selling City Futures: The Financialization of Urban Redevelopment Policy. Economic Geography, 86, 251-274. [ Links ]

Whiteis, D. (1988). The Sundaty Morning Market May Be in Danger, but Thanks to a New Generation of Bluesmen the Music Is as Strong as Ever. The Reader. Chicago, 8. [ Links ]

Wirth, L. (1928). The Ghetto. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Recebido: fevereiro, 2019. Aceite: fevereiro 2019.

NOTAS

i Letter October 30, 1993 to Richard J Daly’s office from Michael Shea of “Buy a Tux” Formal Wear Superstore on W. Roosevelt Avenue, UIC University Archives, Associate Chancellor, South Campus Development Records 003/02/02, Series 1, Box 11 Folder 11-90.

ii Letter November 3, 1993 to Richard J Daly’s office from C. J. Johnson, UIC heard gymnastics coach, UIC University Archives, Associate Chancellor, South Campus Development Records 003/02/02, Series 1, Box 11 Folder 11-93.

iii Ira Berkow Archives – Special Collections – University of Illinois at Chicago, Tyner White 78-16 Box 1, File 1-8, Page 8.

iv City of Chicago Community Development Commission Meeting Report. Public meeting held at 7.00 pm on the 26th day of October 1993 at YMCA, 1001 W Roosevelt Rd. UIC University Archives, Associate Chancellor, South Campus Development Records, 003/02/02. Series X Box 51 File 432, pp: 118-122.

v Attributed to Daniel Burnham (1907), quoted in Hall, Cities of Tomorrow, 174.

vi Hall, Cities of Tomorrow, 181.

vii On smell and abstraction, see Serres, Five Senses.

viii Department of Urban Renewal, “Proposals for Renewal,” 8.

ix Department of Urban Renewal, “Proposals for Renewal,” 17.