Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.111 Lisboa ago. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis15864

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Cemetery tourism in Loures: the value of the transfiguration of a cemetery

Turismo cemiterial em Loures: o valor da transfiguração do cemitério

Tourisme de cimetière à Loures: la valeur de la transfiguration du cimetière

El turismo cemiterial en Loures: valor de la transfiguración del cementerio

Ana Paula Assunção1

1 Doutoranda em “Turismo” do Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território, Universidade de Lisboa, Historiadora e Museóloga, e Conservadora Assessora Principal (T écnica Superior) na Divisão de Serviços Públicos Ambientais/Departamento do Ambiente da Câmara Municipal de Loures, 2674 501, Praça Liberdade, Loures, Portugal. E-mail: paula_assuncao@cm-loures.pt

ABSTRACT

The western necropolis has been structured around a texture of signs and symbols that evoke the memory of the past, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, bring to the present ancient rituals of the search for eternity that have been reproduced since the 18th century. Taking into consideration constant memories, proto-memory, and the philosophy of memory, the fact is that the evocation of what is absent has led to different discourses such as its transfiguration into cultural and tourism assets on a global scale. Since the end of 1990s, the various uses of a cemetery have been emphasized and resulted in differentiated concepts and perspectives regarding tours at the site. As such, it is now common to consider there is a wide set of attitudes vis a vis death and its records. One of the reasons and motivations for this research is also the growth and diversification of the tourist offer. This article compiles the existing scientific information on tourism, specifically cemetery tourism, analyses the above-mentioned approaches; and uses as case study the Loures Municipal Cemetery, in order to draw reliable conclusions and contribute to scientific research in this specific field. One of the main finding aspects of the observation is the hypothesis regarding the possibility of developing cemetery tourism in non-Romantic cemeteries, as it is the case with the Loures Cemetery.

Keywords: Cemetery tourism; transfiguration; non-romantic cemetery; Loures; necropolis.

RESUMO

A necrópole ocidental estruturou-se como uma textura de signos e de símbolos que evocam a memória e a presentificam por rituais que desde o séc. XVIII se reproduzem em busca da eternidade. Trabalhando com as constantes memórias, proto memórias e meta memórias, a evocação do/a ausente tem vindo a permitir a criação de variados discursos, sendo a sua transfiguração em recurso cultural, patrimonial e turístico uma matéria considerada em várias práticas a nível global. As utilizações do cemitério desde o final de década de 90 do século XX acentuaram-se e deram origem a conceitos e perspetivas diferenciadas que rodearam a visita a um cemitério: o cemitério é hoje um repositório de uma variada panóplia de atitudes perante a morte e os seus registos. Este artigo compila a informação j á existente a nível científico, sobre turismo em contexto de cemitério; analisa as abordagens previamente produzidas e aplica um estudo de caso, empírico, cemit ério municipal de Loures, para tirar conclusões fiáveis e contribuir para a investigação científica neste campo do turismo em cemitério. Uma das principais conclusões recai na verificação da possibilidade de prática de turismo cemiterial em cemitérios não românticos, como o de Loures.

Palavras-chave: Cemitério; turismo cemiterial; transfiguração; cemitério não romântico; Loures, necrópole.

RÉSUMÉ

La nécropole occidentale s’est structurée comme une texture de signes et de symboles qui évoquent la mémoire et la présentifient par des rituels qui, depuis le XVIIIème siècle, se reproduisent en quête de l’éternité. En travaillant avec les mémoires constantes, protomémoires et métamé moires, l’évocation du/de l’absent a permis la création de différents discours, sa transfiguration en ressource culturelle, patrimoniale et touristique étant une matière considérée dans différentes pratiques au niveau global. Les utilisations du cimetière depuis la fin des années 90 du XXème siècle se sont accentuées et ont donné origine à des concepts et à des perspectives différenciées qui ont entouré la visite à un cimetière : la compr éhension de ressource l’a emporté, le cimetière est aujourd’hui un répertoire d’un ensemble varié d’attitudes face à la mort et à ses registres. Cet article regroupe l’information déjà existante au niveau scientifique, sur le tourisme en contexte de cimetière ; il analyse les approches pré alablement produites et applique une étude de cas, empirique, cimetière municipal de Loures, pour tirer des conclusions fiables et contribuer à la recherche scientifique dans le domaine du tourisme de cimetière. L’une des principales conclusions est une vérification de la possibilité de la pratique de tourisme de cimetière dans des cimeti ères non romantiques, comme celui de Loures.

Mots-clés: Tourisme de cimetière; transfiguration; cimetière non-romantique; Loures; nécropole.

RESUMEN

La necrópolis occidental se ha estructurado como una textura de signos y símbolos que evocan a la memoria y la tornan presente por medio de rituales que remontan al siglo XVIII y se repiten en busca de la eternidad. Al trabajar con la memoria, proto memoria y meta memoria, la evocación del/de la ausente ha puesto a disposición una variedad de discursos que se han convertido en recursos culturales, patrimoniales y turísticos una materia de investigación considerada en diversas prácticas a nivel global. Los usos del cementerio desde finales de la década de 90 del siglo XX han aumentado y han dado lugar a diferentes conceptos y perspectivas en torno a la visita a un cementerio: prevaleció su entendimiento como recurso, el cementerio es ahora un repositorio de una amplia gama de actitudes ante la muerte y sus registros. Esta investigación también se justifica por el crecimiento y la diversificación de la oferta turística, y está creciendo el turismo cementerial, en particular si se combina con otras ofertas temáticas, como un turismo especial o muy especializado. Este ensayo recoge la información científica existente sobre el turismo en el contexto de los cementerios; analiza los planteamientos antes producidos y pone en práctica un estudio de caso, emp írico, el cementerio municipal de Loures, para extraer conclusiones fiables y contribuir a la investigación científica en este campo del turismo de cementerios. Uno de los puntos principales de observación será la verificación de la posibilidad de visitar cementerios no románticos, como es el caso de Loures.

Palabras clave: Cementerio; turismo cementerial; cementerio no romántico; Loures; necrópolis.

I. INTRODUCTION

The main objective of the article is to create a space for reflection, one that enables time travelling, between what cemeteries were in the past; what they are in the present and what they will be in the future where there might be a link between cemeteries and tourism. Furthermore, it is also important to know more about the state of the art and best global practices, the opportunities and challenges, and the availability and the motivations of tourists/visitors.

This investigation circumscribes Western civilization, Christianity, and reflects on the reconditioning of cemeteries, in the period between the Middle Ages to the present. Our starting point is both the concepts of necropolis and cemetery. Both words have come from the Greek, notwithstanding they bear different meanings. On the one hand, necropolis is the city of the dead, from né kros (dead; corpse) and polis (city). On the other hand, cemetery is “the place where people sleep”, from the Greek word Koimétêrion (place to sleep) and its antepositive koiman which corresponds to the verb to sleep. In fact, this word has started to be used by the first Christians who perceived death as the moment of rest. The cemetery was then a silent place where one would eventually rest.

Christianity thus refers to the burial of the bodies, as stated in Genesis 3:19. Freire de Oliveira (1911) briefly mentions the evolution of the cemeteries until the romantic period: once the catholic religion had flourished Emperor Theodosius issued an order about burials in the city (Rome). However, at this point, burials did not take place inside the churches, but beside the churches in places called cemeteries. There were always objections to burials inside the churches, as it was considered indecorous.

Nevertheless, by allowing exceptions, as mentioned by Ariès (1989), many others wanted to achieve this honour, to a point that the churches were filled with graves (Freire de Oliveira, 1911). In the medieval religious context, the cemetery replicated the organization of the society and thus the clergy and the nobility would be buried inside the church, whilst the indigent would be buried outside. According to Freire de Oliveira (1911) the crowds of the locals, which is to say a high number of deceased, would be buried inside the churches. Therefore, the opening of the graves was taking place long before the bodies that were lying in them were consumed in order to allow for new burials in the same graves. It was certain, then, there was a cloud of corruption spreading through churches, turning funeral prayers into quite dangerous events.

In 1765, Paris’ Parliament issued an edict, which prohibited burials inside churches and determined that the deceased should be buried in cemeteries out of town. The Portuguese health chairman would later propose the same change for the country (Freire de Oliveira, 1911).

The long process of changing mentalities and behaviours then started. In 1804, the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris was inaugurated and its models exported, copied and adapted all over Europe. It was a new level for cemeteries, secular and then based in a new approach. The organization of the space was different, outdoors, with wide avenues, the graves perpetuate social differences between the nobles with monumental graves, the less noble locals in indoor spaces, and graveyards for the less powerful and the poor.

The reproduction of the European practices lead to the import, by those with more means, of architecture models which were placed right by the avenues, with neo-gothic chapels, neoclassical pediments, art-noveau décor, art-déco style, and structures that were more eclectic. Consequently, funerary art was born (Nogueira, 2013). The new conception of cemetery free from the churches’ pressure sustained the cult of memory, according to which the deceased and the living will both be present, as stated by Thomas (1985).

The western necropolis is structured around a texture of signs and symbols, a new type of symbolic field (Catroga, 2010) which guarantees the dead a new form of immortality (Urbain, 1989). Accordingly, there was a different appropriation and a new approach to the cemetery, not only as a place of inhumation, grief and pain, but also as a place of cultural and architectural heritage and memory, after a profound symbolic change (Urbain, 1989). While analysing the cemetery as a document, with references to art, history, experience, daily life, and feelings (Urbain, 1989), it emerges from the original resting space and becomes a site that is revisited as a resource with significant potential for tourism.

This article will precisely focus on the shift of paradigm on cemeteries. In fact, today cemeteries are art, history, experiences, daily live, feelings and a potential tourist demand/offer, a new kind of tourism for a new kind of tourist/traveller of the 21st century. The shift in the pattern of tourists’ travels and motivations have indeed caused the rising of a new special interest tourism, an alternative or niche segment, which may then lead to the consolidation of this segment and its growth opportunities within the tourism market in the next few years (Brotherton & Himmertoglu, 1997). These authors presented the next frontier in the tourism development process considering that it lies beyond the highly packaged destination-based tourism product within the realms of Special Interest Tourism (SIT). They underlined the process of differentiating between 'general' and 'special' interest tourism and tourists by proposing both a general 'tourism continuum' and a new typology of special interest tourists. And cemeteries tourism can have its place here.

The creation of the Association of Significant European Cemetery (ASCE), its recognition and distinction by the World Tourism Organization, has proven the importance of this resource – the cemetery – as it made possible to connect different territories, countries and experiences, as well as revisit history and heritage, and refresh the perspective and insights about cemeteries by giving them a new dimension.

In an important context for the touristic offer approach, one should also consider the conclusions of the 6th Ibero-American Meeting as well as the 1st International Conference for Recognition and Management of Heritage Cemeteries and Burial Art, with the 2005 Morelia International Charter. Those events have refreshed the approach on cemeteries, from an increasingly social and environmentally sustainable perspective envisaging the preservation of local culture and tradition. Many have noted the rise in curiosity about family history. What is striking is that this interest is less about heritage being national and more about it being local. These are all reminders of how the culture of old customs and practices has survived at cemeteries.

Our point of view reflects the close connection between the legacy of the absent and the history owned by the present, given that cemeteries are socially constructed spaces. As such, more than keeping inhumations, the cemetery is cultural heritage, artistic creation, and material civilization of the society. Cemeteries are spaces, which are testimonies, memories, information, and symbols that bind the community and allow for the creation of references and connections to the present.

The material and non-material memory-related values are extremely meaningful and contain a tremendous tourist potential, particularly within the scope of this case study on cemetery tourism in a non-Romantic cemetery, in Loures (Lisbon Metropolitan Area).

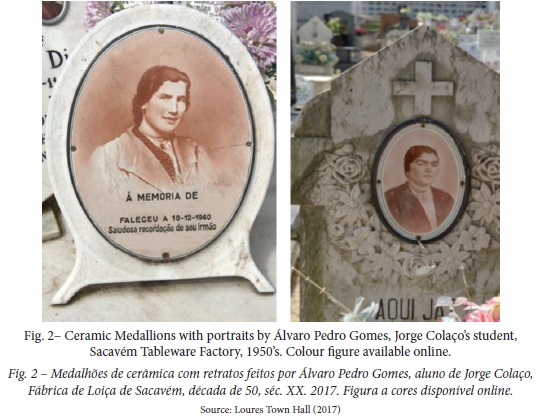

Cemetery tourism has been approached from a traditional standpoint of classic or romantic cemeteries, bearers of great monumentality and sculptures, with a predominant frame of art history or genealogy. However, studies about cemeteries, romantic and non-romantic, together with the experience tested at the non-romantic Loures Municipal Cemetery, are the empirical basis that ascertain that it is possible to accomplish a different model of cemetery tourism, based on local history, and not only in art history, namely through elements such as: mediated tours which value the stonework, ceramic medallions from Sacavém Tableware Factory, important local individuals, associative movements and relevant events such as the 4th October Republic in Loures. This statement is in fact the result of continuous fieldwork, direct observation, and the acknowledgement of the visitors who point out satisfaction levels that have exceeded their own initial expectations.

On the other hand, there is a specific tourism product, which, is developed along the article and responds to a profound search for history, particularly, local life episodes.

II. METHODOLOGY

The starting point for the study of the subject “cemetery tourism in the Loures municipal cemetery” has been the systematic and thorough research about the history of the site together with the identification and research about the people buried in this cemetery. Finally, the dimension of local history was added, both the existing and the one, result from this study and research.

This strategy was rigorously implemented while searching for significance, evidence and sufficiency. The work is developed based on a correlational, interpretative and critical inductive approach. This strategy of rigour and the requirement of meaningfulness and sufficiency is aimed at providing a connection with the values that are at the basis of the formulation of the model of analysis. The critical exam, based on those principles, may lead to new theoretical perspectives. It is, thus, important to uphold this window of principles for the continuous observation of empirical data, which are subjective and, still, reliable.

As stated by Quivy and Campenhoudt (1995) the formulation of the model should respect two conditions: it should be a system of relations; rational or logically built. This strategy thus requires rigour throughout the phases of the project in order to settle a link between research and methodology. The work was developed based on a correlational, interpretative and critical inductive approach in order to question: i) Is it possible to accomplish the transfiguration of the Loures Municipal Cemetery, a non-Romantic cemetery, into a tourist product? ii) Is there added value in it? iii) Is it sustainable?

The burial books, the death records, the records of the memorial permits, interviews to locals and literature of local History were essential to this research and its conclusions. In fact, evidence was found through the research about the various individuals who are part of the History of Loures and are, therefore, key components of the cemetery tourism in Loures. The analysis of the case study was made possible by the implementation of questionnaires of satisfaction by those who visited the Loures municipal cemetery, which, despite their relativity, add reliability to this research.

Our aim is to start from innovative assumptions to integrate the cemetery in the urban grid, which has resulted in greater responsibilities to the cemetery tourism activity, as a segment of the overall tourist offer in Loures. The 21st century brought the need for reframing the cemetery and its potential, combining both the material and non-material cultural heritage that may be visited, with the in situ, which is to say the interpretative, tourist space. The result is thus the basis for the foundation of cemetery tourism in Loures.

III. DIFFERENT TOURIST PRACTICES IN CEMETERY – LITERATURE REVIEW

The term “cemetery tourism” was firstly used in 1992 at the International Congress on Contemporary Cemeteries, with the foundation of ASCE, 2001, and the International Charter of Morelia, 2005, was meant to describe a tourist practice. The concept of the different authors of these important Congress and Charter defined its meaning as being related to the tourist practice in between the cultural tourism in cemeteries and heritage tourism.

Tourism literature reveals significant impacts that postmodernism has had, and is having, on tourism products. This genre of tourism is characterized by the pursuit of new destinations and experiences and by an increasing diversity of products ranging from ecotourism to heritage tourism (Yuill, 2003). Death is part of life and even though it has been avoided, death now has its own place in a post-modern society as an opportunity and discovery of new sensations. The different names that might be given to the practice of tourism in cemeteries and sites related to death and suffering is a result of the various objectives of the tourist, as well as the different packages and offers.

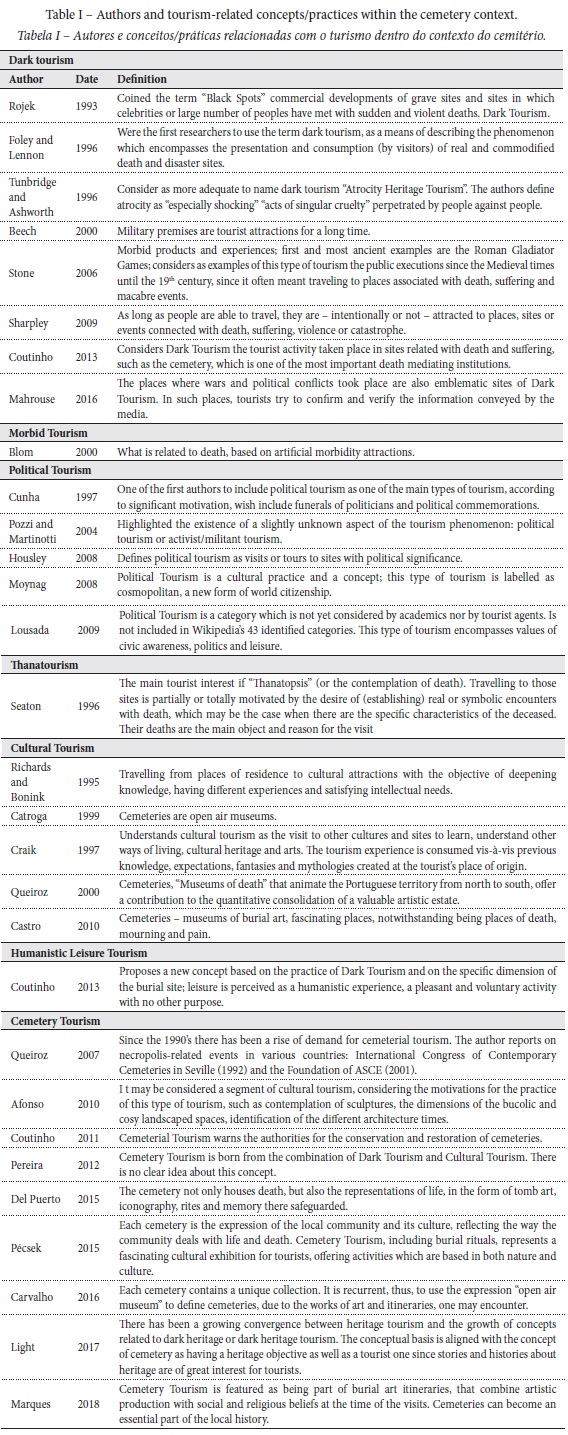

Literature review was organized by dates and concepts to differentiate each author’s concepts regarding this practice. The various authors, and publications that contain fundamental and differentiated concepts regarding tourism in a cemeterial context are presented in table I. However thanatourism (dark, morbid, political, cultural humanistic, leisure, cemetery), one may not overlook the fact that the cemetery is a site of history and life crystallization and, as stated by Coelho (1991) the knowledge of any community will always be incomplete if its cemetery is not included. This article uses the concepts of cemetery tourism (table I).

IV. NICHE TOURISM

According to Simões (2009), there has been a generalization of the term “niche” from 1957, due to Hutchinson (1957), an ecologist who referred to the region in a multidimensional scale and has characterized a series of environmental aspects which have an impact in the well-being of the species. Its application to the field of tourism has been disseminated through marketing ( “niche” marketing).

The regular search for different and non-massified tourist destinations and practices, such as the ones that encourage being closer to nature and culture, started not a long time ago, in 1970s. In a first phase, under the generic name of “alternative tourism”, and later with the name of “specific interest tourism”, “special interest tourism”, or “niche tourism”, which is adopted here (Simões, 2009). Douglas et al. (2001) suggest that special interest tourism or alternative tourism has emerged from the concerns with sustainable tourism. Niche tourism is, thus, related to different motivations and choices, more intimist and genuine. The small dimension of the market is, according to Kotler (1991) a requirement for its definition as a niche, even though growth could also be considered. It was, therefore, taken the opportunity to combine the concept and features of niche tourism with alternative tourism, special interest or niche tourism, in which cemetery tourism may be included. Special interest tourism, as previously mentioned, is a singular, sophisticated and differentiated concept. It means that the tourist’s aim of fulfilling their wish to travel, learn, participate and, ultimately, to know (Simões, 2009).

The cemetery, in itself, as an in situ heritage, has material and immaterial qualities, capable of enabling the fulfilment of such desires and motivations with the experience, sensations and emotions, culture and history. The centre of this heritage and tourism are the way of telling the history and the stories of the people, creating meanings and values. Small groups, that want to be closer to this heritage in an exclusive form, are thus considered. All those concepts are indeed present in tourism activities in cemeteries, which, in this case, is called niche tourism.

These concepts are structuring to insert the Loures municipal cemetery in a logic of tourism of special interest and to base a methodology of work with the objective of creating tourism in the cemetery of Loures.

V. CEMETERY TOURISM IN LOURES MUNICIPAL CEMETERY: A NON-ROMANTIC CEMETERY

Thanatos meets Polis…

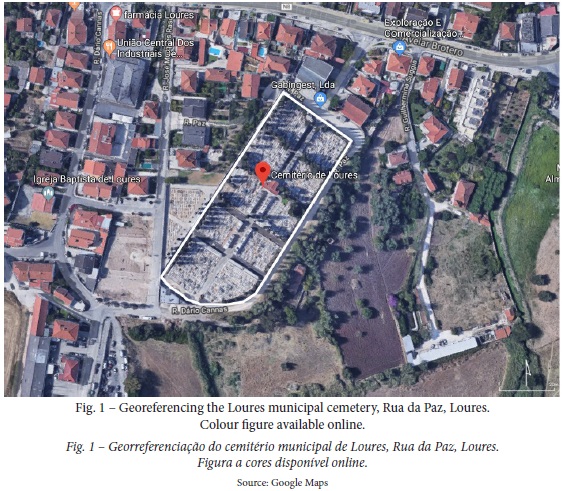

The top of the Quinta do Marzagão, Loures municipal cemetery, is now currently part of the urban grid of the city of Loures and materializes a harmonious set, which is perfectly integrated in the city (fig. 1).

Loures has only been given the category of Municipality on July 26, 1886 and has a long history of a close link to the Portuguese capital city and it development with the Lisbon Metropolitan Area expansion (Santos, 2018).

The Loures municipal cemetery was founded in 1890 and has been operating since then. The first cemetery regulation occurred during the mandate of Anselmo Braancamp Freire, serving as the mayor, and Joaquim José da Silva Mendes Leal as deputy in charge of the cemeteries, 1893. Loures municipal cemetery is a typical example of a 19th century Portuguese cemetery, influenced by the social, special and aesthetic organization of the Cemetery of Prazeres in Lisbon, which was itself influenced by the Cemetery of Paris, Père-Lachaise, and the British Cemetery in Lisbon.

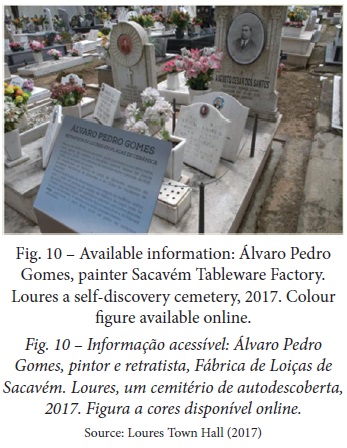

The works on the flowerbeds, with the signature of the workshops, Pero Pinheiro, Montelavar, Póvoa de Santo Adrião, Vila Franca de Xira, Freixial, Loures, Bucelas; the French influences through the usage of wrought and cast iron; the relevance of the ceramic medallion by A.P.G. /Álvaro Pedro Gomes from the Sacavém Tableware Factory (fig. 2); the chapel’s stained-glass windows by Ricardo Leone, the care put into the records – epitaphs, contents, adornments, and traditions created in the cemetery-context – have led to the development of cemetery tourism in Loures.

Loures municipal cemetery’s area is about 1,2 acres and 35% of the total area is dedicated to family graves. The cemetery’s roads have a specific toponomy. The toponymy of Loures cemetery was based on the aim to highlight and honour important individuals or dates of local meaning. Thus, the first avenue was named “Redemption”, following the Republicans’ purpose to “redempt the motherland, demeaned by the decrepit and corrupted monarchy” (text of October 4, 1910 Minutes, shown at the Mausoleum of the Revolutionary Council for the Implementation of the Republic in Loures) (fig. 3).

The Sculptor Street honours Armando Mesquita, sculptor and Master of the Sacavém Tableware Factory; the Writer Street identifies the private plot of the Sttau Monteiro family, where lays Lu ís de Sttau Monteiro, writer, journalist and theatre man; Notable Doctor Street distinguishes Doctor António Carvalho de Figueiredo, insigne doctor and national bacteriologist and renowned Republican. The Firefighter Street is also a way to recognise the historical, social and cultural importance of such a respected local association.

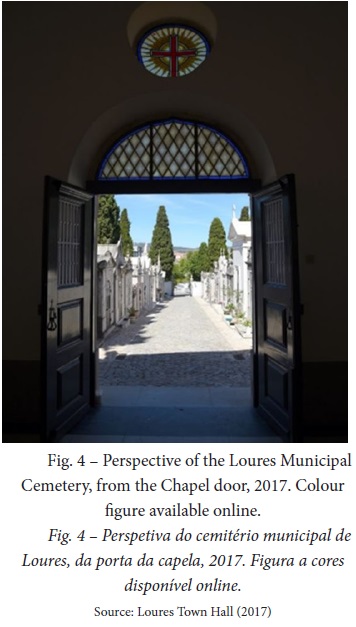

The Chapel that exists in the main Avenue (Redemption) was built in 1958 due to a petition of a group of women from Loures (fig. 4).

Currently in the Loures Cemetery there are: 13 plots; 44 niches of anaerobic decomposition; 64 tombs (municipal concession); 112 niches (municipal concession); 649 family graves (municipal concession); 1068 ossuaries (municipal concession); 1196 temporary graves; Municipal Mausoleum of the Revolutionary Council for the Implementation of the Republic in Loures, 4 October 1910; Private plots for Combatants Firefighters; Sttau Monteiro; Church of Loures; Domingos Pereira.

It should also be referred that this case study concerns mostly the historical part of the cemetery, namely the plots 1 to 5, and the tombs.

1. How did the Loures Municipal Cemetery become a cemetery tourist product?

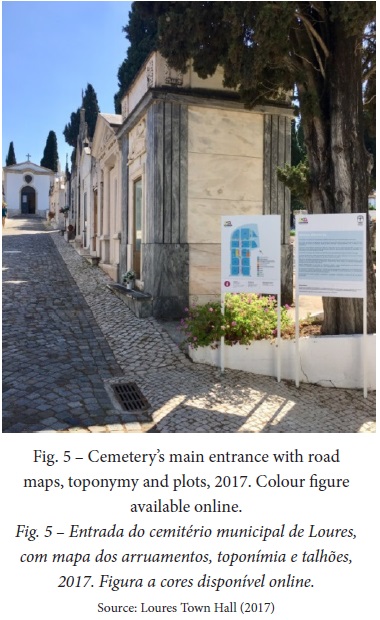

Firstly, the improvement of cleaning, storage and access was available. A clean, neat, organized cemetery with its pavements improved in 2015. Since 2017 there is an information board at the cemetery ’s entrance (fig. 5): history of the cemetery; map of the cemetery roads and numbers, with toponymy, as well as the most relevant plots and the contacts for cemetery tourism visits.

There was an investment by the city council in repair works for the creation of the conditions for the practice of cemetery tourism activities. Moreover, the graphic image was defined as well as a communication plan which were consistent with the municipality’s editorial line. Furthermore, a senior civil servant with adequate qualifications was appointed to develop this project (The cemeterial tourism project applied to the municipal cemetery of Loures was presented to the Mayor of Loures, in 2016, who accepted it and created conditions for its implementation).

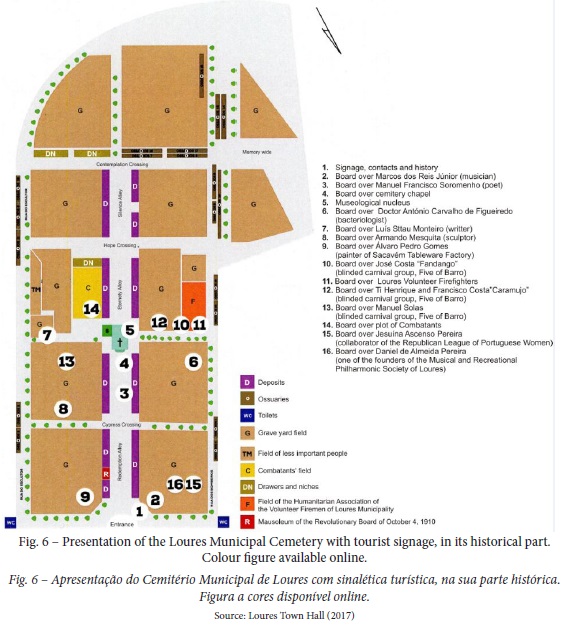

The location of the stainless-steel information boards about the individuals or events which are part of the History of Loures now makes part of a map, available at the Municipal Cemetery Counter and at the Tourism Unit of the Municipality (fig. 6).

Each study has allowed for the formulation of tour itineraries and conversation topics related to the city of Loures, namely its associative, cultural, social and political dimensions, each one with a different information leaflet.

The research on the cemetery and the individuals who have been identified as being closely connected to local history, based on reliable witnesses and study of the burial records, have allowed for the consolidation of knowledge units, by subject or person, which enabled the creation of moments of sharing and personal individual and collective enrichment. Each set originated a free and easy access information leaflet, distributed in several places in the city, such as Municipal Information Centre, Tourism Units, Museums, Archives and Libraries. Consequently, it also led to the creation of itineraries which were made public through the Municipality’s website and Facebook page.

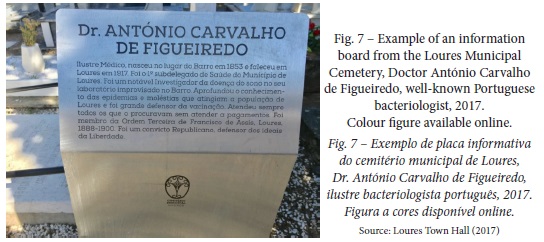

In 2017 there were seven itineraries focused on the lives of the individual’s part of that history. As such, there was attractive information for both communication and visits, which were then analysed through the satisfaction questionnaires, as well as for the evaluation of the cemetery tourism activities in Loures cemetery. The novelty element introduced at the time allowed for an intellectual access to the site through the stainless-steel information boards organized by person or date and proved to be decisive for the transfiguration of the cemetery (fig. 7).

Those actions were crucial and concrete contributions to the understanding and knowledge about History of the Loures’ Parish, at the same time as it introduced a new paradigm of the 21st century cemetery.

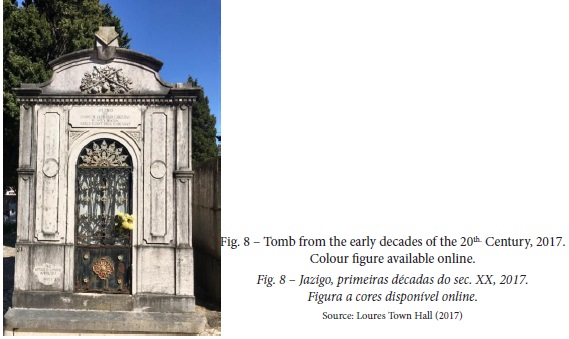

Literature, in general, characterizes sculptures and monuments as fundamental and decisive elements for allowing cemeteries tours. However, in Loures this is not the case. There are only 23 tombs from the early decades of the 20th century. Successive improvement works, which focused on some abandoned or ruined tombs, resulted in them being razed to the ground. Such works have led to profound changes in the cemetery’s configuration, particularly those that occurred in the 1950s, 1960s and 1990s, leaving few records or evidence of the past and history of the site (fig. 8).

As mentioned before, this article’s main purpose is to assess if a non-Romantic cemetery may become a tourist product. Accordingly, the first consequence of the non-existence of great tombs was the broadening of the research scope to include family graves, with municipal concession.

The area corresponding to family graves is about 35% of the cemetery’s total area and includes 649 family graves of 4th and 3rd generations, including valuable records in epitaphs, burial aesthetics and, above all, the main historical figures of the Loures’ Parish society, with important information that support this kind of research.

To unfold history and rise it from the invisible, through research and communication, has allowed for the writing of History chapters, which tourists enjoy listening to, live and feel.

1.1. The role of mediation - Cemetery Tourism implementation

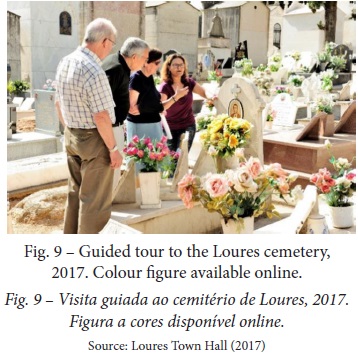

By using the senses and interacting with emotional values, it was possible for each visitor to enjoy moments of idleness (Coutinho, 2013), joy and affective appropriation of the testimony about Loures’ society (fig. 9). The reinterpretation of signs and symbols, religious or profane, professional indicators, Álvaro Pedro Gomes’ ceramic medallions genuinely portraying people with social values have allowed for a unique and exclusive experience, in small groups (12-15 people). In the first mediation the approach of the International Culture Tourism Charter to cemetery tourism (ICOMOS, 1999), was paramount: natural and cultural heritage is a material and spiritual resource, which offers a perspective about the historical evolution.

Cemetery Tourism implemented in the Loures municipal cemetery is an essential experience, worth to be seen, as it has contributed to the construction of a meaningful experience also, in what concerns the concept of cemetery tourism. Information was used as a key element for the quality of the tourist product: the cemetery. The language and discourse allow speaking about the dead as if they were alive, past events as present. The ‘effectiveness’ of the interpretation is the result of an interaction between visitor and interpretive medium, rather than depending solely on the interpretive medium. Visitors are active participants in making meaning at places of death.

It was the mediation put in place with great investment from the municipality, based on the scientific approach to the implementation of the project, which has started to produce results, thus validating the path that was chosen. From each grave to each visitor, there is a chain of information through the mediator, in addition to the boards that were placed near the family graves, and the information leaflets (fig. 10).

Following what was mentioned before, the association between different tourist programmes is an added value and promotes complementarity between them. Consequently, that same association should be considered when formulating a tourist product in order to create a niche tourism.

Furthermore, the image: a cemetery which is organized with respect and is respectful, which cherishes the main local figures by giving them a post mortem acknowledgement and, thus, a merit-based tourist product. It is the heritage of the family graves that effectively promotes the product which then results in packages of local history, a confirmation of the methodology chosen for the research and new approach to the Loures cemetery.

The features of the new tourist thus meet an adequate product. Being allocentric, individualist, and enjoying experiences in small groups, the visitor of the Cemetery embodies a special interest tourist activity.

This niche of interest about the Loures’ History, has become an effective tourist segment and, eventually, contributes to the concept of sustainable city, one that is capable of assembling the objective conditions to nurture and grow, to progress.

Sustainability is extremely important for the cemetery tourism practice in Loures. Caetano (2015) has studied the Loures Municipality from the New Public Governance (NGP) perspective and has considered that the rational use of the resources based on the resilience of each ecosystem is key to a sustainable municipal development. In what concerns the cultural dimension, cultural diversity should be preserved and respected while retrieving values of local identity. Therefore, the practice of cemetery tourism is growing and a rational use of the resources such as the cemetery is in line with the short- and medium-term ambition of Loures. The development of tourism practices in Loures, thus, already includes cemetery tourism. The integrated and strategic vision at the basis of Loures municipal cemetery tourism is, hence, crucial to monitor possible changes. The cemetery is the tourist product. Whether it is through a pre-established or free itinerary, walking around the graves, the engravings and the epitaphs gives the opportunity to experience a site with the same ease as sitting on a bench and listening to the silence. The Loures cemetery is intellectually accessible and begins to captivate interest and curiosities. To understand and discover that a cemetery, which is mostly constituted by flat and perpetual graves, might generate the opportunity for cemetery tourism visits and creates curiosity. When people pass by a group of visitors and hear about burial symbology, the epitaphs or the frames with ceramics or glass, they end up joining the group or coming back for more information and visit the Museological Nucleus and its exhibition (fig. 11).

The whole customer service and exploration process during the visit to the Loures cemetery contribute to the existence of a tourist destination and product within the segment of cemetery tourism which is unique and pioneering in Portugal.

1.2. What are the gains from cemetery tourism to the city of Loures?

The difference, the added value to explore, the standing for a value, the knowledge of the historical figures who gave great contributions to society, are some of the offers that characterize cemetery tourism in Loures municipality.

The tourism that takes place in this cemetery context in Loures brings a high value to the history and local characters, as to their identity and political values, as the Republic in 1910; creates an effective citizenship and possibilities of education and, perhaps most of all, a humanism that receives the greatest signs of appreciation and recognition from those who visit the cemetery. This is not a simple cemetery, it has a high sense of self, of the history that it contains and preserves, is an open air museum with breath, with the mission of elevation and excellence of Loures.

We are not denying the site’s nature, it is relation to death; however, without denying its origin and context, its transformation and new functions give the site new purposes and opportunities: it is a necropolis which is part of the polis and is linked to it through possible and respectful transfigurations.

These are pages of local history and simple, popular or erudite ways of living. It is the profound transformation of the cemetery, from non-relevant and dead, to a living place, full of stories, increasingly transformed day after day.

This approach contradicts Urbain’s (1989) perspective about the simple existence of monotonous and voiceless plains; there is an intense vegetation of signs, deceiving appearances of simple green fields. As such, the conservation of the heritage prevails, now based on new discourses. This metamorphosis is the keynote: there is a place for niche tourism. Such tourism may not only be created but also encouraged and developed.

In conclusion and quoting Pereira and Machado (2014) a new model for the cities will promote a role for the citizen’s quality of life and environmental sustainability. It requires a multidisciplinary, integrated and innovative approach, encompassing the necessary dimensions and elements for a coherent and sustainable development, thus contributing to the continuity and functionality of the cemetery’s heritage; to the development of regular tourism practices; promoting consumption; integrating the environmental heritage in the city.

2. Evidences of transfiguration

Collecting information was decisive to validate the focus of this research. The implementation of an anonymous satisfaction questionnaire at the end of each session throughout the year of 2017, after visits and regular monthly contacts, has allowed for a broader perspective and for the formulation of a model of answers.

This study has allowed for inferring some assumptions, made possible through the collection of data and evidence in order to validate the answers to the research questions.

The data was not overrated; on the contrary, it contributed to the valorisation of the favourable conditions for the development of cemetery tourism. In fact, the methodology questionnaire made it possible to reach a high number of people.

Thus, the questionnaire had a fundamental purpose of colleting empirical evidence to this research. The questions raised were answered by the satisfaction survey and possible to establish conditions for the transfiguration of the cemetery into a cemeterial tourism product some of the results are presented:

The transfiguration of Loures municipal cemetery into a tourist product is a confirmed issue, attested by both the feedback collected through the questionnaire and the municipal investment, which continues, to the present. Not only are there visits being organized in the Loures Cemetery, there is also further development including implementing this project in other cemeteries: S. João da Talha, Bucelas, Sacavém, S. Julião do Tojal. The interest in the project’s expansion to other cemeteries was shown by the local parishes, following the presentation of the Loures municipal cemetery results. The empirical and reliable evidence has made possible to consider the results crucial to structuring the concept of cemetery tourism in cemeteries without romantic tombs or monuments. Mediation was the key answer to this aspect as an added value experience to the actual practice of cemetery tourism. Transfiguration is a social, cultural innovation implemented in a non-Romantic Cemetery.

We can observe the added value brought to the Loures cemeterial tourism activities. There is an affirmative answer due the cemetery tourism activities at the Loures municipal cemetery, which have made it possible to share and promote the knowledge and appropriation with and by the participants throughout the period in which the tours were organized. The Loures municipal cemetery has pointed out the existence of value in History and Heritage tourism mediation and proved the existence of a concrete opportunity to stimulate the transfiguration of the cemetery into a tourist product. There is value in cemetery tourism in a non-Romantic cemetery. This was the feedback given by the participants, the visitors of the cemetery. Moreover, there is value in shifting the cemetery model into a paradigm, which contributes to environmental sustainability. In conclusion, a new paradigm of cemetery tourism in a non-Romantic cemetery was formulated and it should be considered in the existing cemetery tourism practices.

About sustainability: mediating information has created a scenario the historical figures, which inhabited Loures and who, for many reasons, where part of archives and oral history, now constitute an accessible library where books are frequently open. At the same time, there are people interested in having access to such value. As such, it enhances the added value of sophisticated and specialized knowledge and tourism.

Cemetery tourism, heritage education, academic research and articles present a more positive perspective on the symbolism of the cemetery, at the same time as they deconstruct death-related prejudices. As such, those elements are a truly valuable support and basis for developing cemetery tourism activities, even if in a niche scale, being the first steps towards a new approach and practice within the context of municipal tourism.

The preservation of the Loures municipal cemetery for the future and the quality and cohesion of the cemetery landscape were the choices and the basis that made possible its new classification and function as an historic and cultural site of the city and a destination of innovative cemetery tourism.

VI. TRANSFIGURATION

The transfiguration of the Loures municipal cemetery into a tourist product has given a new dimension to the site. Going beyond the Paz Street – the street outside the cemetery – and to be included in tours and itineraries, with connections and interests, which resulted in a historical reshuffle.

From the evidence and data collected, the Loures municipal cemetery, seen as a tourist product, does have this dimension. We are now in a conservation society (Urbain, 1978), however such conservation has a purpose, which was demonstrated by this case study.

It may be concluded that there is an innovative dimension of the cemetery tourism activity and that its practice should be noted and taken into consideration. This experience showed that monumentality allows the existence of a type of cemetery tourism, which is different from what was presented. There are in fact differences not only in terms of mediation, but in terms of also regarding the materials and the reactions of each visitor.

The investment in non-Romantic cemeteries or cemeteries without major tombs or graves is, thus, a new possibility: cemetery tourism is a new trend in a niche segment tourism, which may now include other types of cemeteries, including non-Romantic cemeteries.

This article has paved the way to a significant empirical verification, which has allowed for new appreciation perspectives. In addition, it has also permitted the extension of the practices and nature of cemeteries in the 21st century, now seen as an historical source, combining heritage and tourism.

To conclude, this case illustrates an innovated approach with the non-Romantic Cemetery that is a discovery that may entail new challenges. This was the paradigm that was formulated, an added value that is a derivative of the cemetery transfiguration from a burial site into a tourist product.

In view of the scarce literature on non-Romantic cemeteries where there is cemetery tourism, both at a national and international levels, it is now considered that there is an actual opportunity for new studies in this field, such as those that have been developed, on the Loures Municipal Cemetery. This is one of the fundamental findings of this case study: non-Romantic cemetery, with a new model of understanding, a new sustainability and environmental concern, a real innovation.

REFERENCES

Afonso, L. R. G. (2010). Turismo cemiterial: o cemitério como espaço de lazer [Cemetery tourism: the cemetery as a leisure space]. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal. [ Links ]

Ariès, P. (1989). O homem diante da morte [The hour of our death]. Rio de Janeiro: Alves. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261517717300092#bbib16

Beech, J. (2000). The enigma of holocaust sites as tourist attractions – the case of Buchenwald. Managing Leisure, 5(1), 29-41.

Blom, T. (2000). Morbid-Tourism – a postmodern market niche with an example from Althrop. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 54(1), 29-36.

Brotherton, R., & Himmetoglu, B. (1997). Beyond destinations - special interest tourism. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(3), 11-30. [ Links ]

Caetano, C. (2015). A nova gestão pública e a sustentabilidade no sector público autárquico na óptica das cidades inteligentes e sustentáveis: estudo de caso da Câmara Municipal de Loures [The new public management and sustainability in the local public sector from the perspective of smart and sustainable cities: a case study of the Municipality of Loures]. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Retrieved from https://comum.rcaap.pt/bitstream/10400.26/21985/1/MGP_Carla%20Caetano_Junho%202015.pdf [ Links ]

Castro, E. (2010). Cemitérios em destaque: iniciativas nacionais e internacionais pela preservação do património funerário [Cemeteries highlighted: national and international initiatives for the preservation of the funerary heritage]. [ Links ] Anais do III Encontro Nacional da ABEC, Piracicaba.

Catroga, F. (1999). O céu da memória: cemitério romântico e culto cívico dos mortos [The sky of memory: romantic cemetery and civic worship of the dead]. Coimbra: Minerva.

Catroga, F. (2010). O culto dos mortos como uma poética da ausência [The cult of the dead as a poetic of absence]. ArtCultura, 12(20), 163-182.

Coelho, A. M. (Coord.) (1991). Abordar a morte, valorizar a vida [Addressing death, valuing life]. In Atitudes perante a morte [Attitudes towards death] (pp. 7-11). Coimbra: Minerva. [ Links ]

Carvalho, L. F. N. (2016). Os cemitérios artísticos como laboratórios de estudos [Artistic cemeteries as study laboratories]. Mouseion, 25, 75-89. doi: https://doi.org/10.18316/1981-7207.16.39

Coutinho, B., & Baptista, M. M. (2013). O turismo negro como experiência de ócio humanista-aproximações entre conceitos aparentemente distantes [Black tourism as an experience of humanistic leisure-approximations between seemingly distant concepts]. [ Links ] Atas do III Congresso Internacional em Estudos Culturais, Ócio, Lazer e Tempo Livre na Cultura Contempor ânea, Aveiro.

Coutinho, B., & Baptista, M. M. (2011). Cemitério Central de Aveiro: entre a vida e a morte. [Aveiro Central Cemetery: Between Life and death]. Congresso Internacional «A Europa das Nacionalidades – Mitos de origem: Discursos Modernos e Pós Modernos». Aveiro: Universidadede Aveiro. Retrived from http://mariamanuelbaptista.com/pdf/CemiterioCentral.pdf

Craik, J. (1997). The culture of tourism. In J. Urry & C. Rojek (Eds.), Touring cultures: transformations of travel and theory (pp. 113-136). New York: Routlege. [ Links ]

Cunha, L. A. A. (1997). Economia e política do turismo [Economy and tourism policy]. Lisboa: McGraw Hill.

Del Puerto, B. C., Baptista, C., & Luísa, M. (2015). Espaço cemiterial e turismo: campo de ambivalência da vida e morte [Cemiterial space and tourism: field of ambivalence of life and death]. Revista IberoAmericana de Turismo, 5(1), 42-53.

Douglas, N., & Derret, R. (2001). Special interest tourism. Melbourne: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Foley, M., & Lennon, J. (1996). JFK and dark tourism: A fascination with assassination. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), 198–211.

Freire de Oliveira, E. (1911). Elementos para a história do Município de Lisboa: 1.ª parte [Elements for the history of the Municipality of Lisbon: 1st part]. Lisboa: Typographia Universal.

Housley, W., & Wahl-Jorgensen, K. (2008). Theorizing the democratic gaze: visitors' experiences of the New Welsh Assembly Sociology. The Journal of the British Sociological Association, 42(2), 726-74. [ Links ]

Hutchinson, G. E. (1957). Concluding remarks. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quantitative Biol, 22, 415-427. [ Links ]

International Council of Museum. (ICOMOS). (1999). Carta Internacional sobre Turismo Cultural [International Cultural Tourism Charter]. Retrieved from http://www.patrimoniocultural.gov.pt/media/uploads/cc/cartaintsobreturismocultural1999.pdf [ Links ]

Light, D. (2017). Progress in tourism management, progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: an uneasyrelationship with heritage tourism. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/02615177/61/supp/C"Tourism Management, 61, 275-301.

Yuill, S. M. (2003). Dark tourism: understanding visitor motivations at sites of death and disaster. (Doctoral thesis). Retrived from http://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/4267978.pdf [ Links ]

Lousada, M. A. (2009). Turismo político, consciência cívica e lazer: breves notas [Political tourism, civic awareness and leisure: short notes]. In J. M. Simões & C. C. Ferreira (Eds.), Turismo de nicho: motivações, produtos, territórios [Niche tourism: motivations, products, territories] (pp. 325-338). Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Geogr áficos. [ Links ]

Marques, J. A. M. (2018). Turismo cemiterial o “porquê” e o “onde” [Cemetery tourism the "why" and the "where"]. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento, 29 , 47-63.

Mahrouse, G. (2016) War zone tourism: thinking beyond of voyeurism and danger. An International Journal of Critical Geographies, 15, 330-45. [ Links ]

Moynagh, M. (2008). Political tourism and its texts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

Nogueira, R. de S. (2013). Quando um cemitério é patrimônio cultural [When a cemetery is cultural heritage]. (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro. Retrived from http://www.memoriasocial.pro.br/documentos/Dissertações/Diss321.pdf

Kotler, P. (1991). Marketing management: analysis, planning, and control. 7th ed. NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Pécsek, B. (2015). City cemeteries as cultural attractions: towards an understanding of foreign visitors’ attitude at the national graveyard. Deturope – the central european journal of regional development and tourism, 7(1).

Pereira, P., & Machado, R. (2014). Cidades de amanhã: a integração entre património construído e tecnologias de informação, comunica ção e electrónica [Cities of tomorrow: integration between built heritage and information, communication and electronic technologies]. Revista Ingenium, II(139), 24-27.

Pereira, C. da C. (2012). Turismo cemiterial [Cemeterial tourism]. Instituto Superior da Maia. Retrieved from http://www.trabalhosfeitos.com/ensaios/TurismoCemiterial/557759.html [ Links ]

Pozzi, C, & Martinotti, G. (2004). From Seattle to Salonico (and beyond): political tourism in the second-generation Metropolis. Revista de Economia Pública Urbana, 1 , 37-61. [ Links ]

Queiroz, J. F. F. (2000). Cemitérios do Porto: Roteiro [Cemeteries of Oporto: Script.]. Porto: Câmara Municipal do Porto.

Queiroz, J. F. F. (2007). Os cemitérios históricos e o seu potencial turístico em Portugal [The historical cemeteries and their tourist potential in Portugal]. Anuá rio 21 Gramas, 1, 7-12.

Quivy, R., & Campenhoudt, L. (1995). Manual de Investigação em Ciências Sociais [Research Manual on Social Sciences]. 4.ª edição. col. Trajectos: n º 17. Lisboa: Gradiva. [ Links ]https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/135676679500100205 [ Links ]

Rojek, C. (1993). Ways of escape: Modern transformations in leisure and travel. Basingstoke, Hampshire: The Macmillan Press. [ Links ]

Santos, J. R. (2018). Espaços infraestruturais e vacância: traços diacrónicos da produção do território metropolitano de Lisboa [Infrastructural spaces and vacancy: diachronic traces in the shaping of Lisbon’s metropolitan territory]. Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, LIII(108), 135-159. doi: https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis12057

Sharpley, R., & Stone, P. (2009). The darker side of the travel: the theory and practice of the dark tourism. Bristol: Channel View. [ Links ]

Stone, P. (2006). A dark tourism spectrum: towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibits. An Interdisciplinary International Journal. [ Links ]

Seaton, A. V. (1996). Guided by the dark: from thanatopsis to thanatourism. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), 234-244. [ Links ]

Simões, J. M. (2009). Turismos de nicho: motivações, produtos, territórios [Niche cars: motivations, products, territories]. Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Geogr áficos.

Urbain, J-D. (1989). L’archipel des morts: cimetières et mémoire en Occident [The archipelago of the dead: cemeteries and memory in the West]. Paris: Payot. https://www.worldcat.org/search?q=au%3AUrbain%2C+Jean-Didier&qt=hot_author

Urbain, J-D. (1978). La société de conservation: étude sémiologique des cimetières d'Occident avec 32 photoghaphies et 35 dessins de l'auteur [The Conservation Society: Semiological study of Western cemeteries with 32 photoghaphies and 35 drawings of the author]. Paris: Payot.

Thomas, V-L. (1985). Rites de mort: pour la paix des vivants [Rites of death: for the peace of the living]. Paris: Fayard.

Tunbridge, J. E., & Ashworth, G. (1996). Dissonant heritage: the management of the past as a resource in conflit. Chicherter: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Recebido: janeiro 2017. Aceite: junho 2019.