I. Introduction

Comics, as a form of popular culture, have specific addressability, and various motivations for appearance, depending on the society that created them. This means that they are context specific (Rose, 2014). Either capitalist or socialist, originating from the West or the East, their manipulative power on the masses was theorised and analysed (Booker, 2014; Kuhlman & Anaiz, 2020; Magnussen et al., 2015; Niță, 2001; Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010; Salazar-Anglada, 2019; Stromberg & Kuper, 2010; Teampău, 2012, 2015; cf. also for the role of popular culture, Adorno & Horkheimer, 2002). This type of culture was instrumental during the Romanian communism, depending on the trends in state politics and culture at a certain moment, with differences for its various decades (i.e. under the rule of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, from 1947 to 1965, and Nicolae Ceauşescu, from 1965 to 1989; cf. also Verdery, 1991, for differences of the period before and after Ceauşescu’s July theses; these theses are briefly discussed here).

Comics, a particular genre of both children’s and adults’ books, appeared for the first time in 1827, in Switzerland (Niță, 1992). At the beginning of the 20th century, they become largely available and popular both in Europe and America. Romania takes part in this trend. Romanian magazines host comics in black and white or colour, featuring popular heroes’ stories (Niță, 1992). Later, drawings in comics are forms of spatial representation, contributing to the creation of the new or socialist space narrative, forging identities and imagined communities (cf. Anderson, 1991). Stories of socialist progress are told through visual imagery and written text. These comics are motivational stories. They are relevant for the ideological and pedagogical function of the visual-verbal interplay.

Romanian comics have been marginal so far in comics studies as has been, in fact, research on comics from all former European socialist countries. In this context, the aim of my research is to discuss the social and cultural construction of space and of social classes and their political identities in the Romanian society, using as sources the educational narratives of the comics in a youth magazine. I prove that both places and subjects were produced in the framework of socialist ideology in comics on the topic of socialist work and territorial development. To reach this aim, I chose a pioneers’ magazine - Cutezătorii [The Daring Ones], named further on in this study as Cutezătorii - that appeared at the end of the 1960s in Romania and continued to be published until the Romanian revolution of December 1989. In this research, I based my analysis of visual materials on three sites: of the production, of the image, and of the audience (Rose, 2014). Understanding the site of production was a first step. Previous research shows that highly aggressive propaganda was part of the strategic control employed by the Romanian Communist Party during the last two decades of Communism (Verdery, 1991). Therefore, my research objectives are 1) to identify all comics about work and socialist progress in this youth magazine and 2) to analyse the meanings and messages of the created representations in order to assess if they construct a coherent visual discourse. This is part of a larger research I conduct on visual representations of socialist Romania (including visual imagery from school textbooks and picture postcards).

Comics are profoundly spatial, and this spatiality is not static or fixed, but a dynamic, contingent, and embodied practice, that is why comics are argued to “display a truly post-representational essence that emerges through the performative nature of their reading practice” (Peterle, 2015, p. 71). However, from the spatial representational and non-representational aspects of comics, in this study, I focus on the first type, because those aspects have not been studied so far using this visual imagery in Romania, that is on the topic of socialist work. In addition, my choice of considering only the representational features of these comics help making my argument that they are part of a larger visual discourse on development during socialist Romania (cf. also Ilovan, 2020; Ilovan et al., 2018; Ilovan & Maroşi, 2018). In this study, the larger geohistorical and political context is supported by the ideological materials from the Pioneer’s Guide (Consiliul Naţional al Organizaţiei Pionierilor / National Council of the Pioneers’ Organisation [CNOP], 1985).

In this research, I used texts (visual and written), as the components of a system producing multiple and alternative meanings, depending on the relations among authors, texts, and readers. The elementary item of this research is the representation and comics are defined here as complex texts made of representations. Representations are cultural products encoding the power relations in the society (Hall, 1997b). These complex texts together form the discourse that I analyse in this article.

Which is the intention of the creators of these comics? Which is the key message, the hegemonic meaning resulting from its production? Which is the political, cultural, and social heritage of these work-related comics?

In comics, the images fix the meaning of the story, they restate it, they build on it, they explain it and this process is called “anchorage” (Barthes, 1977). Starting from the definition of the ‘relay” (Barthes, 1977) as the interaction through which “the verbal text can extend the visual text adding new and different meanings”, Francesconi defines and exemplifies the “visual relay” as the process in which the visual text adds information to the verbal text (cf. Francesconi, 2011); for a detailed discussion on image-word interaction). This is the case of the comics as visual and written representations. Drawings are carefully realised, with much attention paid to details, so that to transmit in the best possible way the intended messages.

Visual culture is created within the politics of knowledge production. Thus, it is relevant for research which creates knowledges, how they circulate and transform and the worlds that they constitute. After researching the site of production, the next step consisted of the approach to the visual material of comics themselves. This study presents and discusses the research results of this second stage. The site of visuality I chose is the image. I analyse image-texts and related word-texts in comics produced and circulated in socialist Romania. The critical visual analysis of the comics is possible by making references to some or all three sites (production, image, audience) of this visual imagery. My article does not include any audience study, as this is not the focus of my research, but considers the features of the production site in the form of socialist Romania and the site of the image in comics.

II. State of the art

“Comic book geography” is an emerging field (cf. Dittmer, 2014a), and “an independent cultural geographical area of research” (Peterle, 2015, p. 71; cf. also Dittmer, 2010), combining both representational and post-representational approaches (Peterle, 2015, 2017, 2019). In a temporal approach to research on comics, one of the earliest studies is referring to the propagandistic aims of this media (Mintz, 1979). Comics, as “sequential art”, have been part of Geography’s interest since the 1985 (Eisner, 1985) with a development of research considering the geopolitical messages of this medium (Dittmer, 2007; Dodds, 1996). Along the years, authors studying comics focused on them as sources of memory and narratives (Dittmer, 2014b), as a part of the society (either at national or international level) (Grove et al., 2019), on considering them a historical source due to their reflection of dominant narratives during various historical periods, underlining their role in power relations (Magnussen, 2016), as a new source material for the geopolitical discourses to be discussed in critical geography (Dunnett, 2009), and in the politics of knowledge (Katz, 2013), and especially in creating knowledge to support the building of national identities through representations (Dittmer & Larsen, 2007).

Turning from the studying of their messages, recent literature debates extensively how comics are created and read (Fall, 2006; Peterle, 2015, 2017, 2019), with a fine-grained analysis of their grammar, combining a variety of visual and textual elements that produce both hegemonic and alternative meanings and/or interpretations (Dittmer, 2010; Laurier, 2014), according to a high number of components (speech, feelings, movements, objects, characters, etc.) (cf. Laurier, 2014). Studies underline the possibilities offered by comics for an in-depth understanding of past and contemporary experiences of space (Dittmer, 2010, 2014b; Fall, 2006; Peterle, 2015, 2017, 2019), and their role in opening new understandings for geography, among other sciences. Comics are hybrids of visual and textual resources with a high appeal to students’ cognitive level, engaging their knowledge, memory, opinions, and attitudes.

Educationists were aware of the usefulness of the comics in instruction due to its features and due to its popularity and impact on mass culture (Hutchinson, 1949; Sones, 1944). However, their use in teaching and learning Geography is little recognized so far (Kleeman, 2006), although the last two decades could testify for a rekindling of researchers’ interest in comics (Peterlee, 2015).

Previous research on comics in Romania, focusing on both American and Romanian production and on superheroes, belongs to Teampău (2010, 2014, 2015). Studies on comics in the children’s magazines in socialist Romania are quite recent. Haţegan analyses historical comics in children’s magazines of the 1980s Romania, exploring their place within the ideological discursive creation of the Romanian nation and re-writing of history (Haţegan, 2017b). The topics explored in those comics are ancient history teachings (Haţegan, 2017b) and the communists’ anti-fascist fight (Hațegan, 2016). These are integrated into the national-communist period, built upon the “Dacian moment” and on the “people’s continuity and unity” in space and time (Haţegan, 2017b, p. 292). Another study dedicated to researching comics and propaganda is considering the image of the Other (i.e., the foreigner) in historical comics, in Romania, during Ceauşescu’s dictatorship (Precup, 2015). To sum up, only a few studies (Haţegan, 2017a, 2017b; Precup, 2015) have been realised on the relationship between official propaganda materials and edutainment in mass media dedicated to children and youth in socialist Romania, in the process of institutionalizing the spatial features of the country and of social classes in the society, through a normative discourse.

III. Methodology

Visual approaches have been steadily integrated into the geographical repertoire of methods. Drawing on Ferdinand de Saussure’s work, I considered the sign as the basic unit of language, consisting of two arbitrarily connected parts: the signified (concept or object) and the signifier (the sound or image attached to the signified). The referent, as the actual object, which the sign relates to, was also considered within these relations (de Saussure, 1986). This methodological approach can be applied to research with images and accompanying text, such as comics.

I started my analysis by identifying the signs each image was made of, that is its elements. Secondly, I explored their meaning that emerged from the relationship that the respective signs had with each other and that emerged from their relation to the referent, the object in the real world (Rose, 2014). The question was “What does this sign symbolize?” I tried to answer when looking at the images and when reading the accompanying word-text. I consider meanings as relational within the image (among their signs) and among images. These also further relate to the dominant referent systems and ideologies of socialist and communist Romania.

In addition, I analysed the image-text and the word-text separately. Then, I explored the relationship between the two and how they constructed the visual discourse of the comics. Despite a supposed co-equality between word-text and visual-text in comics, at first sight, also because they are complementary and may be evoking the same knowledge or feelings, the main attraction for the readership is the image. The images of the analysed Romanian comics are entirely hand-drawn. The explicit co-referencing between image and word-text is vital for a clearer message.

The reading of the comics is a matter of experimentation, depending on reader’s imagination and knowledge. As such, there is no final reading of comics. They are open stories, each reading contributing to the construction of meaning. However, my research does not focus on the reception of comics, on their audience, but on the interpretation of their key messages in a peculiar context, that of declared ideological education, under well-defined geographical and historical circumstances: socialist Romania. Messages are made sense of by contextualizing the comics through the respective geopolitical environment. I enquired into the provenance of the visualization in order to be able to understand it. My attempt to outline the relation between geohistorical context and official discourse is necessary to decode the comics. Moreover, the background on socialism and communism in Romania is significant for the understandings of signs and symbols of the comics that their contemporary readers would have had.

Therefore, I asked the following questions: Which are the characters, objects, places, and landscapes represented? To what purpose? Whose point of view on diverse subjects is represented? What themes are emphasized (i.e. work, development, progress, nation, etc.)? On what details is the reader’s attention focused? How do these representations fit in the larger context or with other visual and written representations of the respective period?

Content analysis is part of a critical visual methodology (Rose, 2014). I analysed the content of these images, but without searching for a quantitative validation during this process. I looked for connections between images and the broader cultural context of socialist Romania in which they were created and circulated. I did not use a coding to this end because my sample of comics required rather a qualitative approach more than a quantitative one, which seemed irrelevant to be employed for analysing 21 work-related comics. Another reason why I considered quantitative coding irrelevant in this situation is because it cannot “evoke the mood or the effect of an image” (Rose, 2014, p. 102). Besides contents analysis, I also used compositional interpretation of the images (deriving meaning from the features of the elements of the image and the relationship between them).

To sum up, my research on comics will take into account subject matter (what aspects of the socialist reality were depicted), visual codification in terms of the represented subjects (Rose, 2014; Tani, 2001), verbal codification (i.e., the lexis used) and, finally, the “visual and written cross-modality” defined as the interaction of the two semiotic systems (visual and textual) (Francesconi, 2011, p. 7).

The research material included edited sources for the official discourse: Ghidul Pionierului [The Pionieer’s Guide] (CNOP, 1985), transcripts of political meetings concerning the contents of magazines for children and youth, and comics in Cutezătorii magazine (serialised comics) (CNOP, 1967-1989).

Out of the comics published in this magazine, I selected the ones on contemporary societal issues, concerning work for modernising the society, arguing to be reflecting the Romanian socialist reality. Thus, I chose actuality or contemporary comics, a realist genre, presenting the workers’ daily life or comics of the socialist present, topics, actors, actions, central to socialist Romania and education. There are two types of Romanian comics included in this category: a) about the pioneers’ life, and b) about the development or modernization of Romania. Sometimes, these are mixed. In this article, I focus on the second category.

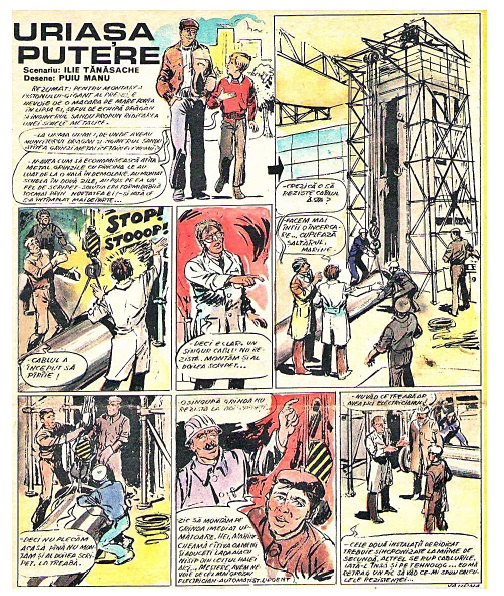

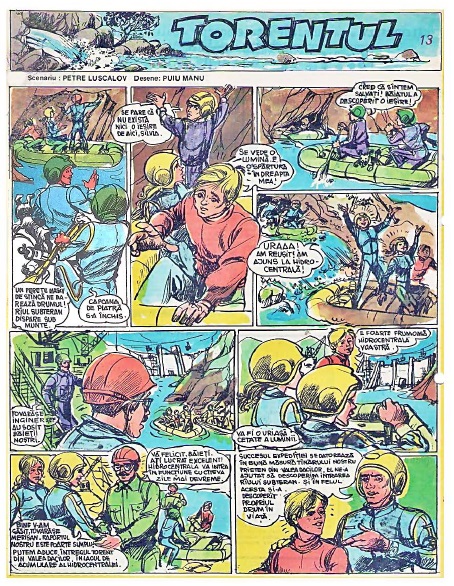

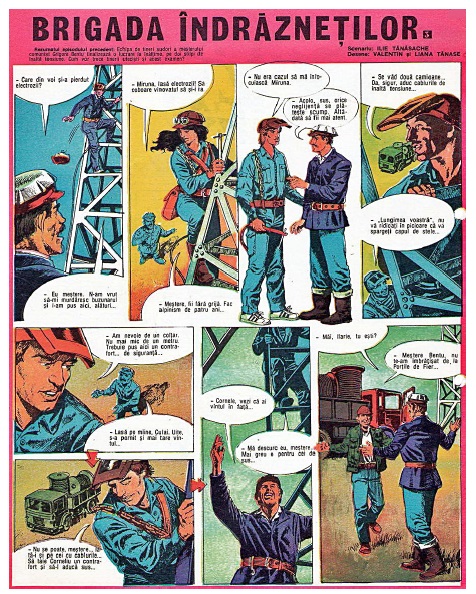

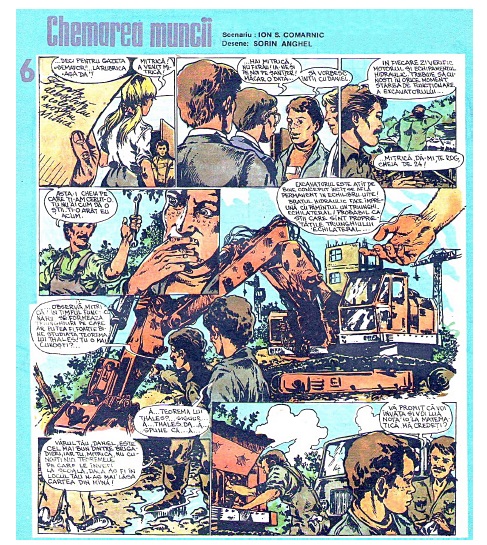

The result of the selection, from all comics published in Cutezătorii, consists of twenty-one stories related to work and development. Acknowledging the impossibility of presenting all entirely, I discuss in detail the following out of the total analysed ones: in 1971, Transfăgărăşanul (9 pp.) and, in 1974-1975, again Transfăgărăşanul (12 pp.), both by Adrian Mierluşcă (script) and Teodor Bogoi (drawings); in 1979, Uriaşa putere [The Great Power] (13 pp.), s. Ilie Tănăsache, d. Puiu Manu; in 1984-1985, Brigada îndrăzneţilor [The Brigade of the Daring Ones] (11 pp.), s. Ilie Tănăsache, d. Valentin Tănase; in 1986, Torentul [The Torrent] (13 pp.), s. Petre Luscalov, d. Puiu Manu; in 1989, Brigadierii (Chemarea muncii) [The Brigadiers (The Call of Work)] (8 pp., left unfinished because of the 1989 Romanian revolution), s. Ion Comarnic, d. Sorin Anghel. However, the discussions and conclusions of the article are based on all twenty-one.

I looked for geographical references that were explicitly mentioned in text or presented in drawings, and also for the presentation of work-related issues: how work was done, features of work (hard, valuable, efficient, on time, etc.), and those working, attitudes, the products of work, the educational and ideological value of presenting working environments to the readers (i.e., the pioneers). Thus, a peculiar geography of work was emerging from these comics, enabling the formation of iconic images of places (the factory, the construction site, the city as a construction site) and of characters (the worker in industry, in constructions; the male worker, the female worker; the intellectual; the pioneer).

Besides the conventional code of the comics (composition of drawings, frames, balloons, etc.), the propaganda code was over-imposed. The representations of space, of actors and of their actions in discourse are deconstructed through the analysis of these comics related to work and development. Both the analysis of written text and of the drawings (visual analysis) were realised. These helped me to find the answer to how space and social classes with their attached political identities were represented and thus constructed in comics: images and related text. In addition, I present the results of a panel by panel and page by page analysis of the above-mentioned five comics.

The following parts constitute the results and discussion. First, I considered the case study of Cutezătorii in the framework of comics and ideological education in Romania in children and youth magazines. Secondly, I present and discuss comics about work and socialist progress in this magazine, with the following sub-chapters: Production of space (a close and descriptive reading of the graphic and textual narrative was realised, but briefly presented here, necessary for readers not familiar with the stories of these comics) and The actors represented in comics, their aims and socialist lifestyles (a discussion of the primary source, showing readers how propaganda made its message transparent and compelling).

IV. Comics and ideological education in Romania in children and youth magazines - the case study of cutezătorii

Niţă and Ciubotariu (2010) identify three periods according to the political regimes of Romania, which influenced the creation of comics: The Golden Age (1891-1947), Socialism and comics (1948-1989), and the period after 1990.

In 1947, a magazine for pioneers appears in Romania under the name Licurici [Firefly]. Its name is changed to Cravata Roşie [Red Tie], in 1951, and again, in September 1967, when it is replaced with Cutezătorii [The Daring Ones]. Comics are published on an irregular basis in its weekly issues, especially starting with 1960 (Niță, 1992). The typology of comics is varied: historical, adventure, science-fiction, and humorous. Comics and propaganda intermingled during the socialist period, as adventure comics (detective, exotic and spy stories) and, after 1950, they also have politics relate topics (Niță, 1992; Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010).

It is acknowledged the fact that, in the 1950s, the new Romanian society (i.e., socialist, and communist) had an important impact on what type (contents, messages) of comics were being published. This type of art was influenced by the political process of remodeling the approach to culture and culture itself. The historical comics is salient in Romania and realised by most of the artists in the field. The magazines for children reflected this trend and Cutezătorii was among the most representative for this type (Niță, 1992). It discussed the pioneers’ duties and finally their moral and societal profile, as requested in The Pioneer’s Guide (CNOP, 1985). The young are informed about the pioneers’ duties and responsibilities (children between eight and 14 years old; after that they were “utecişti” [young communists], in the Union of the Communist Youth): love for the socialist homeland, love for the Romanian Communist Party, love for learning and for work, while to be a daring person is one of the pioneer’s features. Pioneers should also love the duty to be useful to the national economy, then and in the future, and to help at the construction of socialism as proof of their patriotism (CNOP, 1985). So, there were also other ideologically imbued resources that had been delivered by the same institution and could be used by the state in constructing the narratives of the comics and in readers’ decoding their message according to a previously well-known ideological pattern.

The Party’s claims to a monopoly on knowledge, competence and truth in youth magazines is transparent in its political documents, where proposals were analysed and adopted by the leadership of the Ideological Commission within the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party (Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010). Moreover, the supreme leader’s care for language as an identity marker and its cultural value, as well as the strong influence Ceauşescu had on mass media for children and youth can be assessed from his interventions during meetings where the contents of the magazines was established, arguing that the printed media for children had to answer to the principles established at the 11th Congress of the Party, on political education and socialist culture:

the awareness and training for work and life, forming the socialist consciousness, awareness and implementing the principles and norms of socialist ethics and equity, developing the love and devotion of the young generation for the homeland, for Party and for the people. (Ceauşescu in Materials taken over from revista 22, no. 268/2009 and cited in Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010, pp. 258-260, my transl.)

The aim of such magazines is clearly stated in a Note on the printed media for pre-schoolers, primary school pupils and for pioneers, where there are mentioned “the special tasks” that these publications have for “children’s patriotic, revolutionary, and socialist education in preparing them for work and life” (Materials taken over from revista 22, no. 268/2009 and cited in Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010, p. 259, my transl.).

Cutezătorii was among the three most famous children’s magazines, together with Şoimii Patriei [Homeland’s Falcons] and Luminiţa [Little Light]. In comparison to these other two, the comics in Cutezătorii were more elaborated from an ideological and narrative point of view, because the readers of this magazine were older (Haţegan, 2017b). Comics in Cutezătorii were edutainment material for pioneers, where propaganda focused on certain topics considered relevant during socialist Romania. Such a magazine can be considered complementary to students’ education in general, but especially in patriotic education, in History and Geography. During that period, these comics were considered as educational texts or narratives. Their discourse was based on image and text.

In 1967, the year when Cutezătorii was launched, a new Commission on Ideology within the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party was established. The Romanians’ consciousness regarding their country was to be formed by appealing to the values of the Nation and prioritizing concepts such as work ethics and productivity, and progress based on science (Verdery, 1991). From 1965 to 1971, a period of ideological thaw installed (Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010), followed by one of severe ideological constraints (after Nicolae Ceauşescu’s speeches of 1971, named the “July theses”). Under such circumstances, Romanians’ poor living conditions worsen in the 1980s, determining the propaganda to be more aggressive and promote certain topics (Haţegan, 2017b), and reaching its climax during this period (Haţegan, 2016). With Ceauşescu’s “July theses” of 1971, the political regime radicalised the propagandistic role of education, implementing the Marxist-Leninist spirit and principles of education (socialist education, realised through indoctrination from an early age) (Haţegan, 2017b). The “July theses” were considered a milestone for various fields (education, architecture, cultural production, economy) (cf. Zahariade, 2011). Those speeches started the Romanian “cultural revolution”, and comics were part of it (Haţegan, 2017b). Comics highlight what are Communists’ desirable characteristics, while the undesirable ones are attached to the negative characters or to the enemies (Haţegan, 2016).

In Cutezătorii, besides comics with contemporary subjects, they published historical (about 50% or more in years with numerous celebrations) (Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010) and science fiction comics (25%).

The weekly magazine Cutezătorii is representative for the period and comics because it was edited by CNOP, part of the state propaganda, and it was its “expression organ”. No. 1 of Cutezătorii was published on the 28th of September 1967. In its pages, most of those drawing comics (of all genres) in Romania appeared for the first time and then continued to publish (Niță, 1992). In its first years, comics were more numerous (3-4 pages instead of 1-2 pages by the end of the period). Encomiastic phraseology in Cutezătorii was to be recognized also in the texts of its comics.

The magazine is presented as a friend, with the main topics of propaganda listed when the contents is presented. However, themes interesting for children at the respective age are presented, too. The edutainment role is prominent:

To the readers: In our midst, dear pioneers and schoolers, a new friend arrives today: Cutezătorii magazine. In the pages of the magazine, you will be welcomed by the quiver of these historical days, when our people, wisely led by the Romanian Communist Party, creates a more beautiful and richer country, master of its destinies (…). The editorial office. (my transl., no. 1/1967, p. 2)

In schools, interaction with other readers of comics in Cutezătorii was ensured, which was important for creating a fan culture. Therefore, authors’ understanding of the readership’s social and cultural background was used in creating comics at least partly matching readers’/pioneers’ expectations, because “producers’ expectations for clear transmission of narrative are often unmet” (Dittmer, 2010) due to comics’ symbolic openness. Readers of comics are made to wait for the next episode, in the following number of the magazine, where the next key event of the story unfolds. This expectation made the magazine to be a very desired weekly asset.

This magazine hosts a variety of materials, the following three types being the most frequent ones:

a) Propaganda texts, such as those referring to the official newspaper Scînteia la 40 de ani [The Spark at the 40th Anniversary] (no. 32/1971), Să trăieşti şi să munceşti ca un comunist [To live and work in a communist manner] (no. 27/1986), and Patria, Partidul, Poporul [The Homeland, the Party and the People] (no. 51/1986);

b) Texts useful for the pioneers’ education as members of their organization, such as: Regulamentul expediţiilor Cutezătorii [The Regulations of Cutezătorii Expeditions] (no. 13/1970), Redactorii revistei Cutezătorii [The Editorial Office of Cutezătorii Magazine] (no. 52-53/1970), Regulamentul Organizaţiei de Pioneri [The Regulations of the Pioneers’ Organisation] (no. 20/1971), Expediţiile Cutezătorii [Cutezătorii Expeditions] (no. 23/1975), Expediţiile Cutezătorii, şcoala iubirii de patrie [Cutezătorii Expeditions, school for the love of homeland] (no. 50/1988), etc.;

c) The usual texts that refer to the development of the country during socialism, such as text and photographs about Galaţi Factories (no. 20/1968), mass-housing (1918-1978) (no. 45/1978), the metro in Bucharest (no. 47/1986), etc.

Sometimes, readers’ feedback about the magazine is encouraged (e.g., You have the floor, dear readers!) (no. 51/52, 1981). Always the praising feedback, as censorship functioned there, too.

V. Comics about work and socialist progress in cutezătorii

The construction of the socialist society through work is a favoured topic. These comics make for a quarter of those published in Cutezătorii. This part presents the analysis of some of the selected comics about work and of the main actors involved in the plot. Work is presented as the main activity in service of the Romanian state.

1. Production of space

In this part, I present only the results of the description and short analysis of five comics, underlining the role of representations in the production of space, while an in-depth analytical discussion of all these and the rest of the selected twenty-one is in The actors represented in comics, their aims and socialist lifestyles, the next part. The presented narratives are highly explanatory for the representations of space, which is the focus of the first part, and class and political identities, for the second part, respectively.

Images with progress (general development of the country, urbanization, industrial activities, construction activities, etc.) in the Romanian society are frequent on the first cover of this magazine, while comics about work were generally on the back cover. All these images refer to industry, civil construction achievements, public works, reflecting the major development policies of Romania during socialism: massive and forced industrialization, urbanization and systematization of settlements (Ilovan, 2020; Ilovan & Maroşi, 2018). The comics presented here in detail are reflecting these development policies: construction of road infrastructure (in Transfăgărăşanul), construction of infrastructure and plants for the production of electrical energy (in The Torrent), efficient industrial work and production processes (in The Great Power and in The Brigade of the Daring Ones), and construction of mass housing in the urban area (in The Brigadiers/The Call of Work).

5.1.1. Transfăgărăşanul [The Road over the Făgăraş Mountains] (no. 42/1971 - no. 50/1971; no. 47/1974 - no. 4/1975)

It is a comics about the homonymous road built between 1971 and 1974 at N. Ceauşescu’s initiative, having 151km in length and reaching a height of 2,042m in the Făgăraş Mountains, crossing them from north to south. The “road between the cliffs” is presented as it is built by the army, “sons of the Romanian people”, “construction workers in military uniform”, under the leadership of Nicolae Ceauşescu, “the name of the most beloved son of the people, the supreme commander of the army” (my transl., Cutezătorii, no. 42/1971). Transfăgărăşanul is “actuality comics, with workers devoted to the Party cause” (Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010, p. 76).

In Transfăgărăşanul, from the writer’s introduction to the story, we are informed that all that follows to be built is implemented as directed by Ceauşescu, the head of the Romanian Communist Party. The description preceding the first plate runs as follows:

Cut in silex, passing through places where until now the man only walked his sight, cooling its forehead in the everlasting snows of the Făgărăş peaks, arching over indestructible buttresses and on dizzily abyss margins, the bravest road ever built in our homeland falls into place. The honour to open it was granted to the army. The sons of the Romanian people, builders in military uniform, accomplish this mission with the same high responsibility with which they train for defending our revolutionary conquests, with abnegation and heroism, proud to give life to an unmatched architectural work of art, that they relate to the name of the most beloved son of our people, the supreme commander of the army, Nicolae Ceauşescu. (my transl., Cutezătorii, no. 42/1971) Such identification of the workers with the Party was a common trope in the magazines and newspapers of the period (Morar-Vulcu, 2007). The landscape is composed of the mountain, an abyss, and giant machinery, where work is dangerous, but still done by foremen, artificers, bulldozer drivers, trenchers, while they run the risk of losing their lives. That is why they are described as being prudent, attentive, courageous, skilful. Some of the characters have the title of “foremen” and work is a battle: “In Bîlea-Cascadă area, while they conquer metre by metre, cutting in stone the Transfăgărăşan road” (my transl., plate 2, no. 43/1971).

Transfăgărăşanul is published again (no. 47/1974 - no. 4/1975), this time having three more pages than the variant from 1971 (Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010). The comics describes the builders’ (i.e., bulldozer drivers, artificers - military people) heroic deeds in the mountainous area. In the abstract of the first page, we find out the context of the story:

Over the snowy peaks of the Făgăraş Mountains they built a modern road. It will remain over the centuries among the valuable pieces of art of the socialist epoch that we live. The honour of realising this grandiose architecture was assigned especially to our army, to its skilful and brave sappers. The foremen Radu Olaru and Tudor Vrînceanu, lieutenant Pavel Dorin, corporal Ion Cetină and the other military have realised here true heroic deeds. (my transl., no. 47/1974)

The mission is dangerous and consists of getting back a piece of machinery from a lake. The military talk about swimming, one having a diploma for this from the time he was a pioneer. In addition, although not trained as deep diver, one of them has the experience of having worked at the Iron Gates (another major project of the socialist period, referring to Iron Gates I Hydroelectric Power Station, one of the largest in Europe, completed in 1972, with the largest dam on the Danube).

We are told that the place where these men must dive in is Lake Vidraru. Another one helps, even without swimming equipment, but having experience as a fisherman in the Danube Delta. They succeed to take out the machinery from the lake. Bâlea Cascadă chalet is to be seen, as well as the road built by the army, commenting on what is to be admired: the builders’ knack. The first car appears on that road. All mentioned places are iconic ones in the economic and social landscape of socialist Romania, as previous studies on picture postcards and on Geography of Romania school textbooks confirm (Ilovan, 2020; Ilovan et al., 2018).

In this frost, they are climbing the cliffs and the battle metaphor is used, as a new work front is attacked. The military have finished building the road and the comics concludes with congratulatory ideas: “The building of the 27 bridges and viaducts of the Transfăgărăşan required high quality work, courage, and heroism” or “The 27 bridges and viaducts, true works of art, are ready. Work at the grandiose alpine road is about to end” (my transl., 10th plate, no. 4/1975). At the end of the comic story, pioneers are represented celebrating workers’ results.

5.1.2. Uriaşa putere [The Great Power] (no. 45/1979 - no. 5/1980)

The aim of the comics is stated by a character (Codruţ): “you will find out about the work of these people”, in a big factory. They deliver for export. They were ready, but they would have been quicker if others, from other factories, would have delivered on time. The issue of being late is a problem in the Romanian socialist economy where factories depended on one another, based on previous planning, and there was no free market to intervene when such problems appeared.

The characters are workers, engineers, and draftsmen. The battle metaphor for work is used: “The draftsmen, the tinkers, engage in the battle to take up an ultra-urgent command coming from abroad” (3rd plate, no. 48/1979). These are serious comics. We see how people in the factory collaborate to solve a technical problem.

The sixth episode of the comics (fig. 1) shows that there is tension between the workers and engineers, who come with solutions, and the bureaucrats who want only that responsibility is assumed by signing a piece of paper. Workers and engineers are not taking risks; they are very cautious when working with machinery.

The people in the factory are still looking for solutions to new obstacles and their communist work ethics is a strength:

The solution proposed by the technologist has numerous disadvantages. But the fitters in Drăgan’s team and engineer Sandu offer all their experience, the huge communist innovative flux, and they finally find a way. (my transl., no. 2/1980)

The reader experiences very dry dialogues and overall interaction, an avalanche of discussions about technical details and the “lesson of well-done work”. In the end, we find out that in this factory, these “worthy people” realise tools for the chemical industry, and also which is the definition of the great power: “The huge creative power of the collective. And thus, after numerous defeated obstacles, they arrived, in an on the clock race, to the day of starting production” (my transl., 11th plate, no. 5/1980).

Women and girls appear as assistants, secretaries, as replacements of men and boys, as those who congratulate, but not the main characters. Despite the socialist rhetoric about gender equality (cf. Morar-Vulcu, 2007), one sees that work-related comics are dominated by male characters, their decisions, and their actions. As a “natural” conclusion, one might think that men are constructing socialism, enabling development, and thus they are entitled to most of the Romanians’ gratitude and a better place in the social, economic, and political hierarchy.

5.1.3. Brigada îndrăzneţilor [The Brigade of the Daring Ones] (no. 45/1984 - no. 6/1985)

The reader learns that a new and big fire fortress in Romania is the place where the action takes place. The name of the city is not given. We might think that this could be anywhere in the country, due to the swift pace of industrial development. “The call of steel” brings young welders from the big building sites of the country. One plays the guitar, one plays rugby, one is awarded for his work. A welder woman appears after the meeting starts, as she replaces her brother who went to study at the university. A communist master is the leader of this team of welders.

We learn that the woman’s brother was sent to university and should come back to replace the old master. We see that the welders do difficult work at great height. The story underlines that each workday of these Communist youth [Utecişti] welders for great heights is an “exam of will and revolutionary contribution dedication”. The welders’ work is described as we see them in action (fig. 2). Some met before at the Iron Gates, but also other hydropower plants and an irrigation system are mentioned (again, iconic places in Romania during socialism).

The welders discuss how important it is to go to the university. Professional transformation is a topic of the welders’ story, one of the characters going to university for better qualification (as an engineer) and helping the workers when he comes back, working with them side by side, thus increasing the quality of the class. The welder studying at the university - the worker-intellectual - is a representation of a new group - the New Intellectuality (Morar-Vulcu, 2007).

New characters are introduced: a master, a chief-engineer, the steelmakers who are presented through a comment made by a welder: “what a beautiful profession also the steel-makers have”. We are reminded that in the case of these welders, each mission is like a new professional exam. They work well and quickly. Hunedoara, an industrial city, is another evoked site (cf. Ilovan & Maroşi, 2018, for representations of industry in picture postcards circulated in socialist Romania).

Work is described (i.e., description of how the team of welders take decisions about who works where) and we are told that the team did a heroic act in their profession. We learn that their work is finished in record time. The last scene of the comics draws the conclusion of the story, which is always an instructive one: “Friends look how beautiful the furnace kindles the sunset. Not the furnace, Dorin, is such kindled. But (…) it is the work of those who built it from scratch (my transl., 12th plate, no. 6/1985)”.

Source: Cutezătorii, plate 3, no. 49/1984

Fig. 2 The Brigade of the Daring Onesii. Colour figure available online

5.1.4. Torentul [The Torrent] (no. 16/1986 - no. 27/1986)

The aim of the expedition in the story is linked to industrial production: “It is possible that our hydropower plant will function one year earlier” (1st plate, 16/1986). The images introduce us into the story: an accumulation lake, a dam, a building site. The dangerous expedition consists of finding the route of a water torrent. The characters are performance alpinists and swimmers, amateur speleologists, not only workers, and a local boy.

We see how the local boy helps the team to find the entrance of an underground river. They also discover bear fossils and nature is beautiful and impressive. Romania is thus old, authentic, close to nature and modern. The mentioning of the Dacians’ Valley [Valea Dacilor] is evoking Romanian history within an ideological frame: Dacians, who inhabited Romania’s territory more than 2000 years ago, are present through toponymy and often Nicolae Ceauşescu was presented as a modern Burebista, who was the first king of the Dacians.

With the 13th plate (fig. 3), the comics ends and we find out that the mission was successful:

Comrade chief engineer, our boys have arrived; Your hydropower plant is very beautiful; It will be a huge fortress of light; Glad to meet you comrade Merişan. Our Report is very simple. We can bring the stream from the Dacians’ Valley [Valea Dacilor] in the accumulation lake of the hydro power plant; I congratulate you boys; your work is excellent! The hydro power plant will start several days earlier. (my transl., no. 27/1986)

The boy’s behaviour is an example for all pioneers who should help industrial workers and their assistants modernize Romania, which was mostly unelectrified in the rural area.

5.1.5. Brigadierii/Chemarea Muncii [The Brigadiers/The Call of Work] (no. 40/1989 - no. 50/1989)

The title of the comics is rather common among those of the comics about work. That is why, maybe, the title was changed starting with the 3rd plate to The Call of Work. We see children playing football and one is thinking: “Look, how animated is the building site” (no. 40/1989). Another one is thinking: “How fast the block of flats near the school has been risen! As if it has grown right from the earth. Only yesterday there was a hole here” (no. 41/1989). The brisk construction rhythm reflected also in comics (a block of flats appeared in one week, reason for pride), while two are discussing about a third one: “Florin, haven’t you seen him? He was looking at the building site as if he were bewitched!”

The story continued with the 3rd plate and under the new title: Chemarea muncii (The Call of Work) (no. 42/1989). In this plate, one character describes his work: “For two years I have been working on building sites. I go where they need new buildings”. We find out that pioneers are curious to go on a building site. On the building site a bomb from World War Two is discovered. It was thrown there by the “Hitlerists”.

We see workers using an excavating machine and a leitmotif of the communist’s fight against the Hitlerists and fascists, to liberate the Romanian people is introduced. This is just one example of rewriting the Romanian history by Party propaganda: communists’ crucial contribution to Romania’s independence and Romanians’ freedom.

At the same time, on the building site, the main character, a boy (who does not learn enough, but prefers to play football), realizes how important is Mathematics to understand technology and work on such a site (fig. 4).

The daily programme of the boy is described: work on the building site and study at school. The choice for sustained work is motivated in a conversation with the workers, on the building site, and then, at home, with his school mates: “Come on guys, don’t you understand that what I want can be obtained only with sustained work? (…) I promised the brigadiers that I will get 10 in Mathematics” (my transl., no. 49/1989). This is a model of behaviour proposed by the comics to all its readers (i.e. Communist pioneers).

We see, together with the characters, “How the big city grows” (no. 50/1989). In Romania, ideological consumption of space was promoted, not a touristic one:

In the beginning, everything seems very hard, but in time you get used with the life rhythm on the building site. Then (…) the great gladness to see how the city grows before your eyes, like a flower in a gardener’s hand; (…) Wow, your postcards are so beautiful! Have you been in all these places (…), or did you receive them?; These are no simple postcards, Mitrică. These are photographs that help me remember. Not of holidays (…); To each photographed building I helped myself, besides other thousands of colleagues (…). Look, this is how I write my “Memoirs”! (my transl., no. 50/1989)

The plates of this last comics are interrupted three numbers in a row by the magazine’s presentation of the building achievements (“foundations”) of Ceauşescu’s epoch, realized with the devotion of the workers and of the necessary intellectuals. The young readers of the Cutezătorii magazine might have been disappointed that in those three numbers the so much expected drawings that should have been on the last page were replaced, but, in fact, these images were perfectly inserted into the story: the working class had a revolutionary character (i.e., the Marxist proletarian revolution, workers fighting to free themselves from the oppression of capitalism), changing the “face” of Romania.

Source: Cutezătorii, plate 6, no. 45/1989

Fig. 4 The Call of Workiv. Colour figure available online.

Through the plot of these comics, the reading of the Romanian space and society is ensured, an ideologically correct mapping of socialist Romania provided. And this ideologically correct reading is based on the following key representations: industrial development, development and modernization of infrastructure, urbanization, and the connected construction sector. The natural landscape is conquered and controlled through technology which is seen as the direct result of Romania’s policy of modernization. Such choices of topics and geographical settings in comics are not innocent. Iconic images were created through repeating certain signs and, in this process, teaching the viewers was paramount in culturally constructing the “correct” meaning and interpretation and thus making propaganda efficient, at least in theory. These comics are constructed explicitly to support contemporary political and economic decisions on development.

The institutional patronage of the National Pioneers’ Organisation and of the Romanian Communist Party which oversaw its activities was transparent not only in the ideological articles of this magazine, but in its comics, too. Work-related comics incarnated the “truth” of the transition to modern Romania. The overarching public discourse during 1948-1989 Romania is that all this development is possible due to the implementation of the socialist and communist ideologies and goals.

The work-related comics mediate pioneers’ appropriation of knowledge about places and characters that they cannot perceive directly or of which they can have only partial direct perception. This mediation is imbued also with ideological information about the New Man and the New Society and makes the political and cultural messages of the comics more poignant. Due to propaganda, the richness of textual details (either in images or word-texts) is quite high, as the comics were intended to educate the young according to certain values, not only to entertain them. Their purpose was to regulate children’s social behaviour underlining the sacrifices and value of constructing the New Man as the Superworker.

2. The actors represented in comics, their aims, and socialist lifestyles

The characters in comics are defined by the places where they interact. These places and the peculiar plot produced to accommodate those places are significant for the characters’ identity. In addition to representations of space, the constructions of the social and political categories take visual form in comics.

The centrality of class is visible in how the comics are constructed, and gender is another topic according to which social difference is explored in the work-related narratives. The visualization of these comics proposes certain roles ascribed to characters, who are representative of social categories, and naturalizes hierarchies concerning class and gender. The institutional power of the Romanian Communist Party is made transparent in work-related comics, with an insistence on power relations among social classes and between these and the political and economic systems.

Class identities, like all types of identities, are constructions influencing people’s relation to place, space, to society, and they were partly articulated by the official or political ideology and discourse of the communist period. Comics are representations of the social/class/political hierarchy in the socialist society. There are cultural, imagined, and elusive boundaries between classes. The subjects who are centrally positioned, “exploiting a powerful centre-margin discursive dynamic” (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006, cited in Francesconi, 2011, p. 10) are either human or machinery or working tools. The most represented in the twenty-one analysed comics are the following categories: the workers, the intellectuals, the army, the militia, and the pioneers. In the following, I present the first two categories, based on their relationship in socialist Romania, as the dominant classes in the discourse about work and development (i.e., economic and territorial), and approach the other in a future study.

5.2.1. The workers

Work in the Romanian socialist society was one of the key values proposed and advertised by the state (cf. Cucu, 2019), besides the homeland, the Party, and the people. Creating the identity of the New Man and of the new society in Romania, also in comics for the youth, answers the questions about whose interests are represented and for what purpose (Niţă & Ciubotariu, 2010). Comics about the working people portray prototypical individuals, representatives for the whole class of workers and for that of intellectuals. Workers in the construction sector and in heavy industry are overrepresented, while no attention is given to workers in agriculture. Therefore, peasants are not present in work related comics in Cutezătorii magazine. The ideological message here is quite transparent: industrial workers and the assisting intellectuals matter for the development of Romania, while peasants do not, although Romania had more than half of its population living in the rural area and most of it was working in agriculture.

The class identity of the characters is concomitantly essential - pertaining to individuals being part of the respective class - and non-essential, palpable, as those characters realise certain actions characteristic to their class (i.e., workers working on building sites) or non-characteristic (i.e., helping intellectuals, helping the young - the pioneers). However, they are represented in the same way in all these comics, individuals of a class share the features, needs, interests and goals with their peers, they behave similarly. Singular individuals of the same class (i.e., workers) are not vivid due to personal features, but represent normative characteristics of their belonging, all of them under the overarching topic of heroism in work.

The workers are already legitimated from an ideological, political point of view. Intellectuals are part of the working business, but seemingly individuals within their group are not to be trusted in all situations. The workers are adequate to the new society, they are building it, thus answering the Party’s will and call, so they are legitimate from an ideological, political, economic, moral, and overall societal perspective. Their representation is as monotonous as the urban landscape workers are building.

The comics represent only workers in heavy industry and especially those in the construction sector. The latter is more often represented, as they are directly related to the transformations of the Romanian landscape (cf. da Costa, 2016, for a discussion about landscape and nation), the products of their work are visible and also helping the light and heavy industry when constructing the necessary infrastructure for the functioning of factories. The workers represent the “hard nucleus” of the working class, more politically competent and therefore better from a humane point of view, as argued by Morar-Vulcu, based on his research of the official discourse of the socialist media (Scînteia newspaper) (Morar-Vulcu, 2007). This respectability is given by the workers’ experience, age and industrial sector.

The comics advocate for the usefulness of the workers and helpfulness of the intellectuals and of the young in building the perfect socialist society (cf. Hațegan, 2017a, for an analysis of its features, during the 1980s). Their stories are as many manifestos for continuing the heroic work done so far. In fact, the last story, The Call of Work, although unfinished because of the regime fall in December 1989, epitomizes this overarching idea. The intellectuals and the young only support the workers.

The identity of the young ones is very well described in these comics, as they are considered important actors in the Romanian society, besides workers and intellectuals. They will be the future workers and intellectuals. The discursive strategy of power, either visual or written text, is the reiteration of the characters’ features, such as: love for work, love for the country, heroism, and honesty. The worker has the role of a metonymy for the entire class, whose main features were that of physically building socialism.

The pedagogical action of the Party is highly transparent in these comics. However, these were not the only means for the Party’s pedagogical action, but the only one discussed in this study. Thus, the workers in the comics are active, against the background in which the regime asks for more work in less time (Morar-Vulcu, 2007). The workers have an aim, which is clear to the reader (either young or not), which is proved through the physical presence of their work results: a new dam, installing a water pipe in the mountains so that the new textile factory can begin functioning, a new road, a new machinery that creates products needed for export, etc., according to the demands of the Party and of the workers’ class. The Superworker is imposed as the idol of the young in socialist Romania, similarly to Superman in the American culture and capitalist society. However, the Superworker has no special powers like Superman’s, but his are those approved of by the socialist ideology. He is “real”.

Some of the workers in comics have skills that are not characteristic to their job but help them get it done better or faster: they are good athletes. There is a similarity between work and sports competitions. Other are artistic (e.g., playing the guitar), so quite close to what the pioneers could assess as appealing.

As a rule, these comics about work are quite serious, some serious jokes appear now and then, to cut out of the boredom of the story, if necessary, such as the one in which the daily life of the welders is presented and where a woman character as a worker is introduced for the first time - treated respectfully by the team. However, also a joke is played on her, questioning her competence: it appears that she welds (or somebody else does) her safety belt to the place she sits while welding. Nevertheless, the conclusion is that she is a good, competitive worker, doing her job and assisting her male colleagues. In some comics, jokes or any kind of humour are non-existent (the reader is having a hard time learning the lesson of the comics, like in the The Great Power).

In addition, comics try to break the stereotype that women are not as good workers as men but based only on one story. However, the universe of these work comics is a profoundly masculine one, women and girls appear (when they do) as helping assistants to male heroic deeds. Except for the woman-welder, part of the welders’ team (the team is in fact the main character of the story), women are never the main characters, either as workers or intellectuals. Their role is secondary in modernising the country and in constructing socialism. Other times, they appear as negative characters’ helpers (in couples of criminals, fugitives, etc.) or even not understanding the innovation proposed by the male character, trying to stop him, and asking to be excused in the end, for not understanding; or being submissive or not courageous enough (the standard is that imposed by the main character). The canonical actors of the official discourse give a masculine definition of workers and of work images, which were reinforced in the Romanian society for decades after [cf. Kligman (1998), for gender relations in socialism, and Gal & Kligman (2003), in postsocialism; cf. also Monk (2018), for an overview on advances in the interest in gender within socialist and postsocialist countries].

The conscious worker is underlined in these comics, as work is above personal life, life is dedicated to finishing work, and to finding the best solution. Workers seem intrinsically motivated; they are represented as models for the young and possibly also for other classes. The general cause of the society is higher than any other need or interest of the workers. The stories of these comics stand for that.

5.2.2. The intellectuals

Intellectuality is a binary actor. It is both licit and illicit, as it is formed of the two groups: the old one and the new one (the latter, educated during socialist Romania). Within the two groups of intellectuals, one can identify the progressive one (faithful to the people) and the regressive one (Morar-Vulcu, 2007). Both these types are represented in the comics about work, with the former group in more than 90% of the represented intellectuals.

So, its global legitimacy is not possible like in the case of workers, as the group is less homogenous. In these comics, the new intellectual gets involved into physical work, as in the case of the welders’ story: a former welder, studying at the university, comes to practice in his team. However, although receiving former workers as members, intellectuality is discursively subordinated to the class of workers. Intellectual work is necessary, but less ideologically relevant, as presented in the comics. The real work is done by the workers.

A process of reification is visible in the comics where a class helps another. Help is welcomed and awarded, it is an exceptional feature of characters who are helping: intellectuals and workers helping each other, pioneers helping the intellectuals and the workers, workers helping the pioneers.

Helping those in distress, similarly to friendship, is considered an age-specific theme (Haţegan, 2017b), but, as Morar-Vulcu shows (2007), these actions had also an ideological function: sacrifice for the revolutionary cause is another topic of the comics, either historical (Haţegan, 2016) or work-related, creating a certain educational atmosphere for the communist youth.

3. Some final remarks on representations in work-related comics

The constitution of the scenes and of the entire stories of these comics is realized with a pedagogical purpose and they have a moral and value-related message: advertising the key values presented by the Party propaganda. Through my study, I argue that comics were pedagogical tools for teaching about socialist Romania. In this article, one of its key values was foregrounded: work for the people, for socialist construction. In these comics, a sign of equality is used between socialism and modernization in the form of the industrial sector and the constructions one. The reader is mostly presented with the spatial meanings of the setting which is advertised (whether factories or urban areas under construction). The reader’s construction of spatial meaning is invited to be realized in the same ideological framework. Their instructional messages are visible through the choice of characters, places, and plot.

Comics, as a cultural form, ensured the production and exchange of meanings about development, about societal renewal through work, and thus contributed to children’s interpreting meaningfully their living environment. Encouraged to make sense of the world based on the same representations, their broadly similar understandings, and signifying practices (Hall, 1997a), helped create an imagined community. The comic narration constructs geographical spaces and places that the reader might identify or identify with, creating thus place-attachment and community attachment. Particular places are connected to peculiar, imagined communities (cf. Dittmer & Larsen, 2007). In these work-related comics, work-related places are connected to the Romanian imagined community of the working people. This community is represented as a homogenous one. And because it works for achieving socialist goals, it is overlapping ideologically the political community of the Romanian Communist Party, as it reflects what it means to work and live in a communist manner.

Party propaganda used comics as efficient teaching tools, especially because of their power to engage the reader in the story, in co-creating it though the process of reading (Peterle, 2017, 2019). Thus, comics are provided to the Romanian children also as fictional exercises of investigating geographical and historical issues, past and contemporary. Comics improve students’ ability to think actively (Peterle, 2015) and, in the analysed case, their understanding of places and people in an ideological-driven approach to development. The difficult appropriation of ideology is made easier to understand by employing comics thus actively engaging pioneers in the learning process.

These comics foreground contemporary heroes of the socialist Romania. Their features and jobs are varied, but the common denominator is work. They are either working people or aspiring to be (i.e., in the case of the pioneers). A Superworker, the New Man of communism, is forged in the image of the worker in comics. The worker is associated with masculinity in the modern discourse and is representative of a collective identity.

In these comics, individual identities are subordinated to the collective ones and to work, as a supreme value of the socialist society. Work is presented as the only relevant practice in the social production of space and landscape. The scripts of the comics are based on metaphors of duty (to the people and to the Party) and of work, legitimizing through discourse certain values and aims. Although workers’ life must have been hard, as representations in the comics inform us, the message is that it is worth it, for ideological and societal reasons that the workers are aware and approve of. So, the representation is that such a life is a fulfilling one.

The battle metaphor and the path metaphor are part of an official normative discourse. They are central to how social reality and group identities are represented and should be perceived. The military paradigm of work is represented from the very beginning in this type of comics. This fight metaphor was imported from the historical field to that of work. History, as well as the economic circumstances of the period, were under the influence of communist ideology, where revolutionary achievements and the fight to accomplish aims were leitmotifs.

A coherent representation of work in the past as a top value and of a life worth living in socialism is possible due to two factors: a coherent discourse about work during that period and the psychological one (Tani, 2001; Zahariade, 2011). Workers’ life is romanticised: being in the building site should be everyone’s wish, joy and pride.

This article offers a context-sensitive academic reading of cultural production exploring discourse through the context of its writing and reception (Sharp in Dittmer, 2010; Rose, 2014) and, at the same time, I rehabilitate subjectivity as part of scientific research (cf. also Dittmer, 2010), adhering to the cultural and visual turn in geography.

As distinctions between production and consumption of literary geographies is hard to draw through a clear boundary line, textual production and consumption being rather blurred processes (Dittmer, 2010), my research refers to both processes, although the focus is on the product, the discourse of the comics, strongly connected to the ideological “intentions” of its production. Due to the accompanying propaganda word-text or due to intertextuality in the social and cultural context imbued by symbols, a hegemonic understanding of the narrative prevails. The dominant ideological (i.e. socialist-communist) visuality of reading the comics is not challenged in these official images produced under the guidance of the political system. If challenges exist, they are posed by the readers, but only a study on the reception of this official visual discourse could answer such a research question.

Even though the readers produce their own narrative based on the same montage, I argue that the transparent ideological message does not end up unrecognizable, but, on the contrary, because of the intertextuality effect on reader’s meaning production, the reader is able to “read correctly” the visual propaganda text. The empirically identified and political imagined audience of these comics are the pioneers, and they learned a specific visuality, as visualities are ‘specific to spaces and times’ (Dittmer, 2010).

Moreover, further studies may show that there is no significant “disjuncture between this discoursively-produced ‘audience’ and the actual readers’ practices to foster divergences in the understandings of the work itself” as Dittmer concludes referring to comics in general (Dittmer, 2010, p. 233). My research can ground future studies showing that “visualities can be understood as learned visual literacies that enable an audience to be active readers of a particular visual culture” (Rose, 2007, quoted in Dittmer, 2010, p. 226). The ideology-driven stories of comics are a particular case in which the readers’ freedom in interpretation is not as limitless as theory might suggest. Despite the multiple possible narratives of visual imagery, in the case of ideological comics, one interpretation is still preferred. The visual discourse of the comics uncovers the Party’s visual framework for making meanings in socialist Romania. “The preferred meaning (or ideologies) become preferred readings” (Rose, 2014, p. 133), the audiences maintaining interpretations that retain “the institutional/political/ideological order imprinted on them” (Hall, 1980, p. 134, quoted in Rose, 2014, p. 133).

Dittmer points out, nevertheless, that he accepts that divergent understandings are not particular to comics. More so, these Romanian comics addressed to children are not characterized by a high degree of iconic abstraction which could lead to more interpretative freedom and interpretative work. On the contrary, their messages are quite straight forward and easy to understand, proposing a series of representations of iconic places, characters, objects, and activities that pioneers have been already familiarized with from complementary sources delivered in school and throughout the Romanian society.

VI. Conclusions

This is a study on space as constitutive and produced through comics (Dittmer, 2014a) and of characters produced in a certain geographical and historical context: socialist Romania. The pedagogical employment of comics serving ideology is not new and research so far uncovered this (Dittmer & Larsen, 2007). However, this is the first study on work-related comics and their propagandistic and educational role in a marginalised space, that of socialist Romania. The socialist and communist ideologies were imposed coercively by the Romanian Communist Party, and, in the case of pioneers, my research showed that Party propaganda used edutainment to foreground its version of the world, serving its political and economic interests. Another contribution of this study is that it fills a gap concerning empirical data and theory on visual discourse in the same period of Romania, completing thus previous research on picture postcards and Geography school textbooks (cf. Ilovan, 2020; Ilovan et al., 2018; Ilovan & Maroşi, 2019).

An analysis of the comics about work and socialist progress in Cutezătorii youth magazine showed how space and the political identities of the young were constructed. Comics reflected the behavioural norms and the values (aspirations) of the Romanian socialist society as framed by the Romanian Communist Party. These were not necessarily accepted in or congruent with the reality of socialist Romania, as not all groups are represented, and the normative discourse might have not been accepted by all in the represented groups. However, the power of these representations cannot be underestimated, as the tools to transmit them were effective: through the educational system and overall propaganda.

In comics, architecture itself was a visual discourse pervading people’s life. The natural landscape is scenery for places where workers tame nature. Images in comics explain how nature is modelled with new heavy machinery and explosives, and how the future symbols of progress are created by the working people in their fight to construct socialism and a better life for everyone.

The discourse of the comics is an educational one, it assesses characters, it establishes their morality or lack of it, it concludes which is the normal or abnormal stance in a certain situation, throughout the development of the story and to its end. The universe presented in these comics is a rather masculine one. If the main represented workers are the men, also the new face/landscape of Romania is the product of male work achievements: mass-housing neighbourhoods, industrial objectives, industrial landscapes, the entire urban area sometimes.

Specific elements or images render the salience of a certain type of message about the success of Romanians’ socialist life and society. Heralding the national sentiment in working for the homeland, in constructing socialism, the present is associated with the triumphant industrialisation that led to urbanisation and soon to the disappearance of rural or peasant lifestyle as the young knew that major, civilising transformations were announced.

My study has in common with other research on comics the confirmed assumption that representations of places and people always make particular arguments. There are various ways to think about images, in this case, drawings, and to study them, to do research about them. The novelty of my research consists of the focus on territorial development and the production of socialist identities as “pictured” by this visual imagery and accompanying texts.

A limitation of this study is one common to the use of visual imagery in research: there is no guarantee that the meanings of images are shared between producers and interpreters (cf. Rose, 2014). Secondly, my reading of these comics is a subjective one. One may argue that the readers of this article saw in my analysis what I wanted and guided them to see. I am part of the constructed knowledge that I “deliver” as a geographer and researcher. This limitation is partially solved because mine is, nevertheless, a contextualized reading and an intertextual one (other texts contributed to the analysis, and, as an author, some knowingly and some unconsciously, were used by me to write this study - an academic discourse on an ideological one; one could argue in fact that any discourse resides on a certain ideology; Rose, 2014). Further research could discuss how these representations on the values promoted during socialist Romania influenced the postsocialist discourse.