I. Introduction

The calcareous territories in the western Iberian Peninsula possess great originality regarding flora and vegetation (Costa et al., 1998, 2001, 2002; Lousã et al., 1994, 2002; Neto et al., 2009). Among the main reasons for this originality, stands out the pedological factor associated with the ombrotype horizon, which promotes decarbonation by lixiviation. As a result of these biophysical particularities, it is not strange that communities of complex phytosociological affiliation occur here. The Cistus scrub communities in eroded, decarbonated, limestone-derived soils, present in the Iberian Southwest, have been placed in the Ulici argentei-Cistion ladaniferi alliance (Lavanduletalia stoechadis, Cisto-Lavanduletea; Rivas-Martínez et al., 1990). However, heathlands from the Dividing Portuguese biogeographic sector, dominated by Ulex airensis and Erica scoparia, were put together with the Ericenion umbellatae, Ericion umbellatae, Ulicetalia minoris and Calluno-Ulicetea communities (Costa et al., 2002; Espírito-Santo et al., 2000). These communities have some floristic affinities with the Cistaceae dominated scrublands.

Furthermore, Rivas Goday (1964) proposed gathering the classes Cisto-Lavanduletea and Ononido-Rosmarinetea into a single class, Cisto-Rosmarinetea, for the Iberian Peninsula western territories, even though they possess different soil pH levels, due to the fact that these scrublands contain a set of common plants, including: Rosmarinus officinalis, Carex hallerana, Lithodora prostrata subsp. lusitanica, Teucrium capitatum, Teucrium fruticans, Coronilla juncea, Ulex eriocladus, Cistus salviifolius, Cistus albidus, Cistus monspeliensis, Helichrysum stoechas, Helichrysum serotinum, Ruta chalepensis, Ruta montana, Thymus zygis, Thymus mastichina and Phlomis purpurea, among many others.

Facing such a background, this article studied the scrublands occurring in eroded, decarbonated, limestone-derived soils from the Iberian western and southwestern territories, as well as their phytosociological affiliation.

II. Material and methods

The vegetation relevés were collected according to the sigmatist and dynamic-catenal phytosociology approach (Braun-Blanquet, 1979; Géhu & Rivas-Martínez, 1981; Rivas-Martínez, 2005b). The biogeographical and bioclimatological typologies used in the description of syntaxa followed Costa et al. (1998, 2012), Rivas-Martínez (2007), and Rivas-Martínez et al. (2001, 2002), while the syntaxa nomenclature followed the fourth edition of the International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature (ICPN; Theurillat et al., 2021). A floristic-statistical group analysis (Müller-Dombois & Ellenberg, 1974) was used for community definitions and synthetic table arrangements.

Ordination and clustering methods were used to describe the circumscription of the new suballiance and plant communities. For community comparisons, the original relevés were obtained from different authors: Lavandulo sampaioanae-Cistetum albidi relevés 1-6 from Santos and Ladero (1988), relevés 7-19 from Belmonte (1986); Phlomido purpureae-Cistetum albidi relevés 20-22 from Rivas-Martínez et al. (1990), relevés 23-32 from Pinto-Gomes and Paiva-Ferreira (2005); Ulici airensis-Ericetum scopariae relevé 44 from Espírito-Santo et al. (2000), relevés 45-53 from Costa et al. (2002), relevés 54-57 from Lopes (2001), relevés 58-60 from Gaspar (2003); Cisto ladaniferi-Ulicetum argentei relevés 82-87 from Braun-Blanquet et al. (1964), relevés 88-91 from Rivas-Martínez et al. (1990), relevé 92 from Lousã et al. (1989); Genisto hirsutae-Cistetum ladaniferi relevés 93-97 from Rivas Goday (1964), relevés 98-100 from Rivas-Martínez et al. (1990), relevés 101-106 from Lousã et al. (1989); Ulici eriocladi-Cistetum ladaniferi relevés 107-118 from Rivas-Martínez (2005a), relevés 119-121 from Rivas-Martínez et al. (1990); Lavandulo luisieri-Ulicetum jussiaei relevés 122-131 from Costa et al. (1993); Thymo villosi-Ulicetum airensis relevés 132-141 from Costa et al. (1997); Salvio sclareoidis-Ulicetum densi relevés 142-165; Thymo sylvestris-Ulicetum densi relevés 166-175; Teucrio capitati-Thymetum sylvestris relevés 176-185 from Capelo et al. (1993); and Sideritido lusitanicae-Genistetum algarbiensis relevés 198-212 from Pinto-Gomes and Paiva-Ferreira (2005). These 212 relevés were submitted to cluster analysis (UPGMA) with the Bray-Curtis coefficient as the resemblance measure and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) using SYNTAX 2000 software (Gower, 1996; Ludwig & Reynolds, 1988; Podani, 2001). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) is a multidimensional scaling method that can be based on any similarity or dissimilarity index, making possible the use of ecologically meaningful indices (Chae & Warde, 2006).

III. Results and discussion

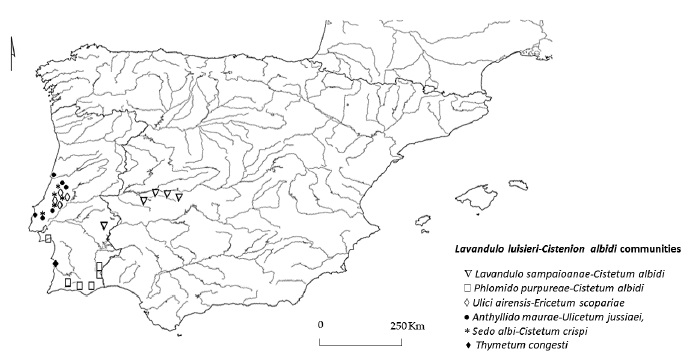

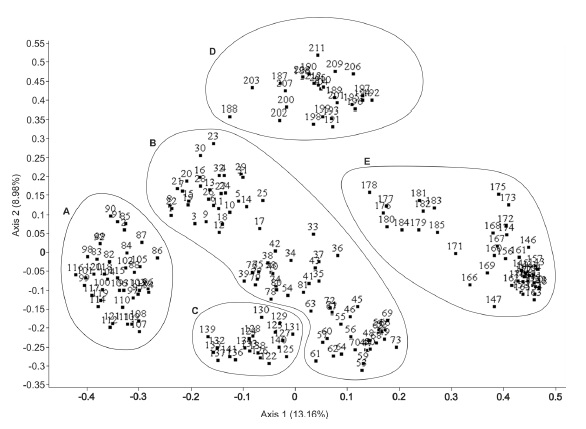

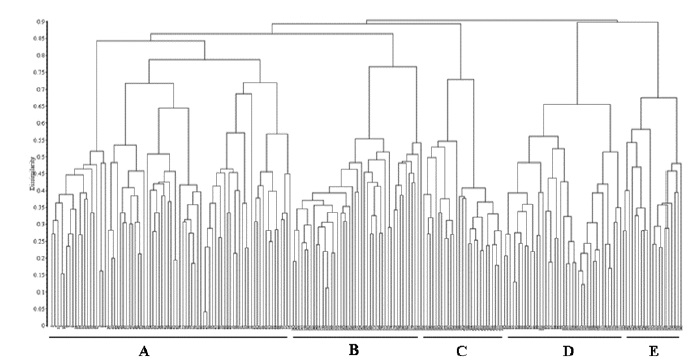

From the ordination obtained by the PCoA (fig. 1) and from the cluster analysis UPGMA (fig. 2) for all relevés, five different groups emerged, validating the segregation of the newly proposed suballiance: Lavandulo luisieri-Cistenion albidi . The remaining four groups included the relevés from Ulici argentei-Cistenion ladaniferi, Saturejo-Coridothymion capitati, Ulici densi-Thymion sylvestris and Ericion umbellatae, which occurred in the same territories and frequently met the associations of the new suballiance.

Syntaxa: A Ulici argentei-Cistenion ladaniferi; B - Lavandulo luisieri-Cistenion albidi; C - Ericenion umbellatae; D - Ulici densi-Thymion sylvestris; E - Saturejo-Coridothymion capitatae.

Fig. 2 UPGMA with the Bray-Curtis coefficient applied to the relevés composed by the syntaxa. Syntaxa: A - Lavandulo luisieri-Cistenion albidi (relevés 1-81); B - Ulici densi-Thymion sylvestris (relevés 142-185); C - Saturejo-Coridothymion capitatae (relevés 186-212); D - Ulici argentei-Cistenion ladaniferi (relevés 82-121); E - Ericenion umbellatae (relevés 122-141).

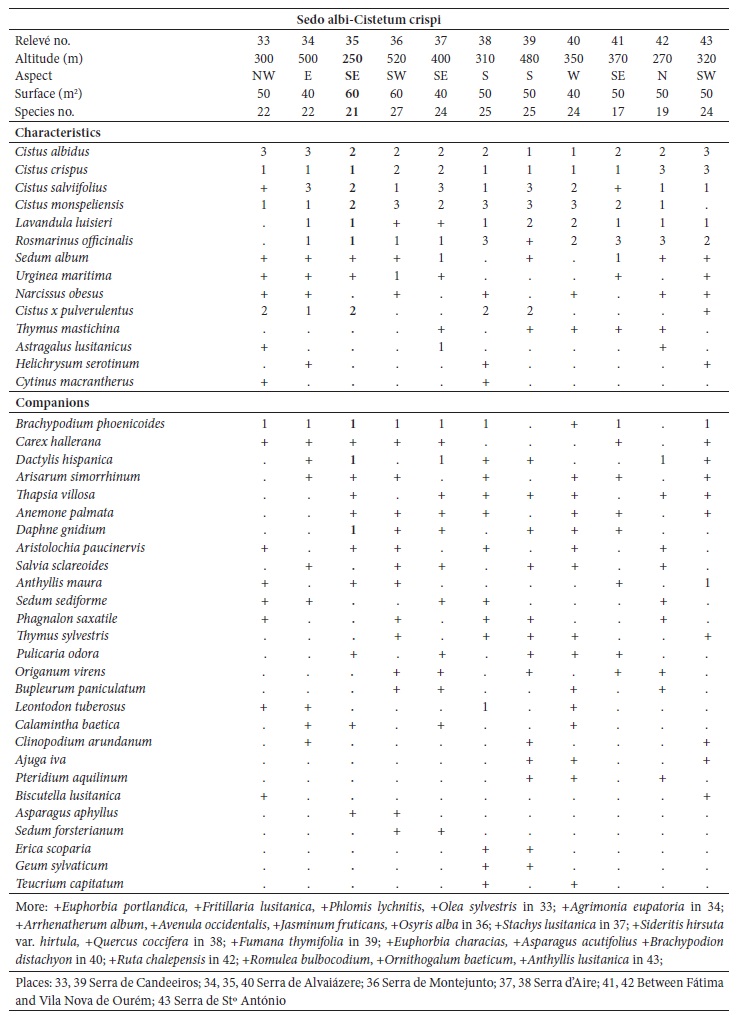

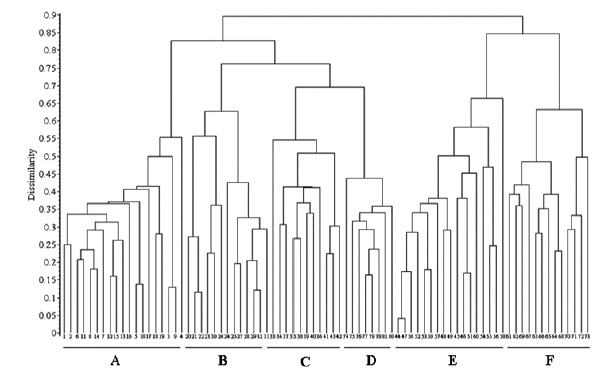

The relevés analysis of the new suballiance, the Lavandulo luisieri-Cistenion albidi communities, made by cluster analysis UPGMA showed a good separation with high dissimilarity of the six associations, including three new associations (fig. 3), discriminated by their biogeography: in the Alentejanean and Pacensean districts the Lavandulo sampaioanae-Cistetum albidi; in the Algarvian, Aracenesean and Arrabidanean districts the Phlomido purpureae-Cistetum albidi; in the Coastal Vincentine district the Thymetum congesti and in the Dividing Portuguese sector the Ulici airensis-Ericetum scopariae, Anthyllido maurae-Ulicetum jussiaei and Sedo albi-Cistetum crispi.

Fig. 3 UPGMA with Bray-Curtis coefficient of the associations from Lavandulo luisieri-Cistenion albidi alliance. A - Lavandulo sampaioanae-Cistetum albidi (relevés 1-19); B - Phlomido purpureae-Cistetum albidi (relevés 20-32); C - Sedo albi-Cistetum crispi (relevés 33-43); D - Thymetum congesti (relevés 74-81); E - Ulici airensis-Ericetum scopariae (relevés 44-60); F - Anthyllido maurae-Ulicetum jussiaei (relevés 61-73).

The floristic and ecological affinities between the chamaephytic Cistus scrublands and the nanophanerophytic heathlands from the Sadensean-Dividing Portuguese, Algarvian and Lusitan-Extremadurean regions, thermo to mesomediterranean, dry to humid, in skeletal soils derived from decarbonated limestone, red soil (leptosols, chromic luvisols and cambisols of the karstic Jurassic) support to propose a new syntaxon at the suballiance level: Lavandulo luisieri-Cistenion albidi J.C. Costa, Pinto-Gomes, C. Lopes, Neto, Monteiro-Henriques, Arsénio, V. Silva, Capelo, Lousã & Rivas-Martínez suball. nova hoc loco. This new syntaxon is affiliated into Ulici argentei-Cistion ladaniferi (Lavanduletalia stoechadis, Cisto-Lavanduletea). For the suballiance holotypus we elected: Ulici airensis-Ericetum scopariae Espírito-Santo, Capelo, Lousã & J.C. Costa in Espírito Santo, Lousã, J.C. Costa & Capelo (2000, p. 119-120).

The soils are neutral-basophilous, the pH in water varying between 6 and 7 being a lower unit in potassium chloride solution; they are decarbonated, originating from calcareous materials with a high percentage of organic matter, where the calcium from the limestone is dissolved in substantial amounts (Cabrita & Oliveira, 1964). Layers of these soils have a high percentage of organic matter normally higher than 10%, and it was also noted that there is a positive correlation between the calcium called “chemically active limestone” and the largest deviations between the sum of individually determined bases of exchange, for this reason in these soils the calcium ion is bound to organic forms (Cabrita & Oliveira, 1964).

We consider as characteristic species of this new suballiance Ulex airensis, Thymus camphoratus subsp. congestus and Cistus × pulverulentus (Cistus crispus × C. albidus), as their ecological optima occur in this sort of conditions. The silicicolous species Cistus salviifolius, Cistus monspeliensis, Lavandula luisieri, Urginea maritima, Thymus mastichina and Astragalus lusitanicus, as well as calcicolous plants such as Cistus albidus, Rosmarinus officinalis, Anthyllis vulneraria subsp. maura, Salvia sclareoides, Thymus sylvestris, Teucrium capitatum and Avenula occidentalis occur as differential; the acidophilous heathland species like Erica scoparia, Genista triacanthos, Calluna vulgaris and Ulex jussiaei are also common (table I in appendix 1).

The Lavandulo luisieri-Cistenion albidi suballiance occupies a middle position between the Rosmarinetea officinalis and Cisto-Lavanduletea classes, as shown by the PCoA results (fig. 1), even though it is closest to the Cistaceae dominated scrublands of the Ulici argentei-Cistenion ladaniferi associations. Despite the ecological and floristic affinities with the Rosmarinetea officinalis, typical of eroded limestone-derived soils, the constancy of the degree of coverage of Cistus species (C. monspeliensis, C. salviifolius, C. crispus) and Lavandula luisieri led us to integrate it in Cisto-Lavanduletea.

The following associations are included in this new syntaxa:

Lavandulo sampaioanae-Cistetum albidi M.T. Santos in Rivas-Martínez, Lousã, T.E. Díaz, Fernández-González & J.C. Costa 1990 (relevés 1-19; Rivas-Martínez et al., 1990).

A mesomediterranean association, dry to subhumid, with a Lusitan-Extremadurean distribution, on chromic luvisols and lime regosols originating from Cambric, Carboniferous, and Miocene limestones. It is dominated by Cistus albidus, and its differential species are Lavandula sampaioana, Cistus ladanifer, Thymus zygis, Retama sphaerocarpa, Teucrium fruticans, Picris comosa and Ruta montana (Belmonte, 1986; Santos & Ladero, 1988; table I in appendix 1) and subserial of Rhamno fontqueri-Quercetum rotundifoliae holm-oak forests.

Phlomido purpureae-Cistetum albidi Rivas-Martínez, Lousã, T.E. Díaz, Fernández-González & J.C. Costa 1990 (relevés 20-32; Rivas-Martínez et al., 1990).

A neutro-basophilous association, on dolomitic limestone (chromic luvisols) substrates of the thermomediterranean, dry to subhumid, original from the Algarve region, subserial of Rhamno oleoidis-Quercetum rotundifoliae holm-oak forests, characterized by Cistus albidus, Phlomis purpurea, Lavandula luisieri and Cistus monspeliensis (Pinto-Gomes & Paiva-Ferreira, 2005; Rivas-Martínez et al., 1990; table I). This association is also observed in the Guadiana lower basin (Capelo et al., 1994; Lousã et al., 1999) and was affiliate to the edapho-xerophilous series of the Phlomido purpureae-Junipero turbinatae S., and in Serra da Arrábida it was integrated into the Viburno tini-Querco rivasmartinezii S. (Costa et al. 2005; Lousã et al., 1999).

Ulici airensis-Ericetum scopariae Espírito-Santo, Capelo, Lousã & J.C. Costa in Espírito-Santo, Lousã, J.C. Costa & Capelo 2000 (relevés 44-60; Espírito-Santo et al., 2000).

An association in cambisols derived from karstic Jurassic limestone, humid to lower hyperhumid, mesomediterranean, occurring on Limestone Massif district, from Alvaiázere, Aire and Candeeiros mountain ranges, of Dividing Portuguese sector, and subserial of Lonicero implexae-Quercetum rotundifoliae holm-oak forests. It was characterized by the nanophanerophytes Ulex airensis and Erica scoparia (table I in appendix 1), with the following differential species, regarding the Thymo villosae-Ulicetum airensis, Anthyllis vulneraria subsp. maura, Salvia sclareoides, Thymus sylvestris and Teucrium capitatum.

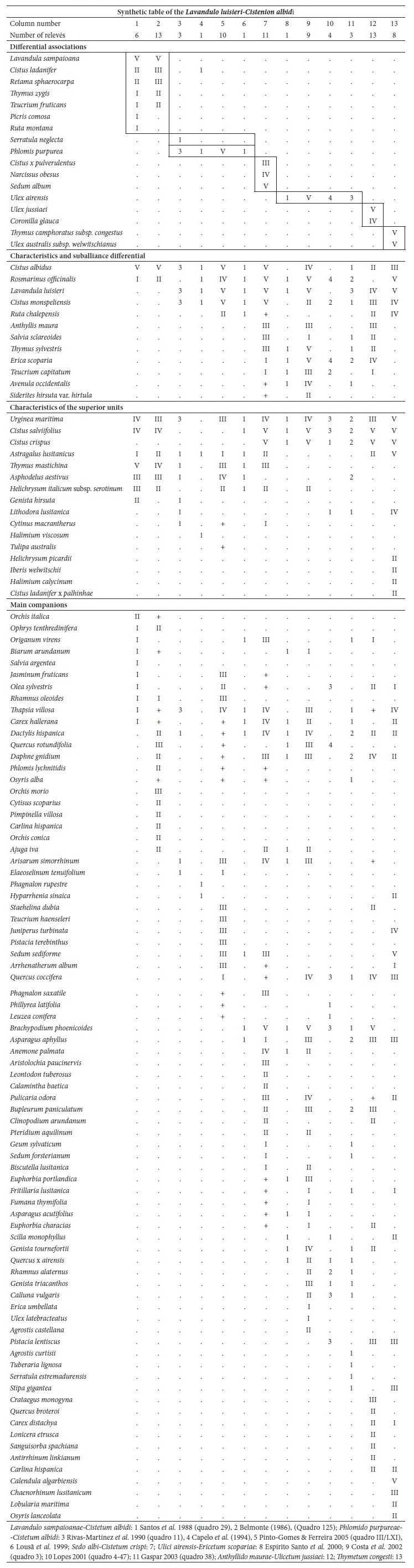

Anthyllido maurae-Ulicetum jussiaei C. Lopes, J.C. Costa, P. Gomes, Lousã & Ladero in J.C. Costa et al. 2021 ass. nov. (relevés 61-73; Community of Erica scoparia and Ulex jussiaei C. Lopes, 2001; Lopes, 2001).

(Holotypus: relevé no. 70, table II in appendix 1)

Scrubland dominated by Ulex jussiaei and/or Erica scoparia, nanophanerophytic, mesomediterranean, upper subhumid to humid, in skeletal decarbonated soils derived from limestones (marl, marly limestone, and hard limestone) of the northern and western Dividing Portuguese sector (Sicó, Rabaçal, Boa Viagem and Montejunto mountain ranges). Its floristic combination includes: Ulex jussiaei, Erica scoparia, Coronilla glauca, Cistus crispus, Lavandula luisieri, Cistus salviifolius, Cistus monspeliensis, Anthyllis vulneraria subsp. maura, Astragalus lusitanicus and Urginea maritima; with the differential species, regarding the Lavandulo luisieri-Ulicetum jussiaei, Anthyllis vulneraria subsp. maura, Thymus sylvestris, Cistus albidus, Staehelina dubia, Teucrium capitatum, Antirrhinum linkianum and Silene longicilia (table II in appendix 1). It represents one of the most degraded seral stages from the Arisaro-Querco broteroi S. woodland series.

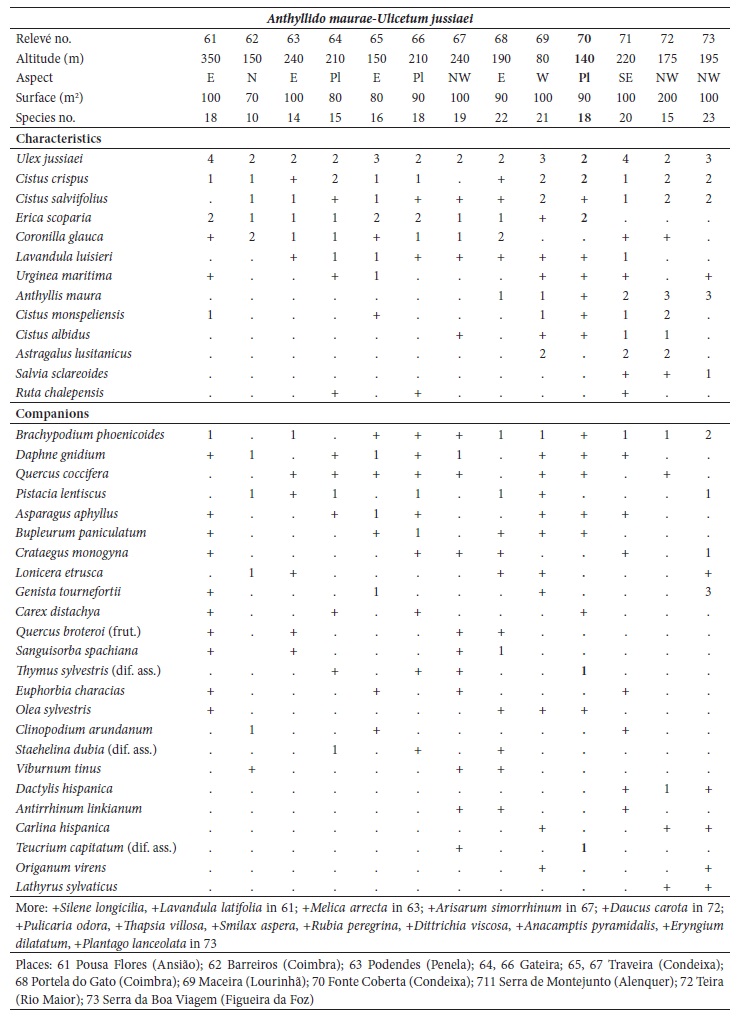

Sedo albi-Cistetum crispi J.C. Costa, Neto, P. Gomes, Lopes, Monteiro-Henriques, Arsénio, V. Silva, Capelo, Lousã & Rivas-Martínez in J.C. Costa et al. 2021 ass. nov. (relevés 33-43; Costa et al., 2021).

(Holotypus: relevé no. 43, table III in appendix 1)

An early succession chamaephytic association, mesomediterranean, subhumid to humid, from the limestone mountain ranges of the Dividing Portuguese sector. It occurs on eroded soils (leptosols) derived from decarbonated red soils and hard karstic limestones from the Jurassic. It is constituted of several species of Cistus (C. albidus, C. monspeliensis, C. crispus, C. salviifolius, C. x pulverulentus), Lavandula luisieri, Rosmarinus officinalis, Sedum album, Brachypodium phoenicoides, Narcissus obesus and Thymus mastichina (table III in appendix 1). It is ascribed to the calcicole series of Lonicero implexae-Querco rotundifoliae S. and Arisaro-Querco broteroi S., where it represents one of the highest degradation stages, the first one to recover, being synvicarious with Phlomido purpureae-Cistetum albidi and Lavandulo sampaioanae-Cistetum albidi.

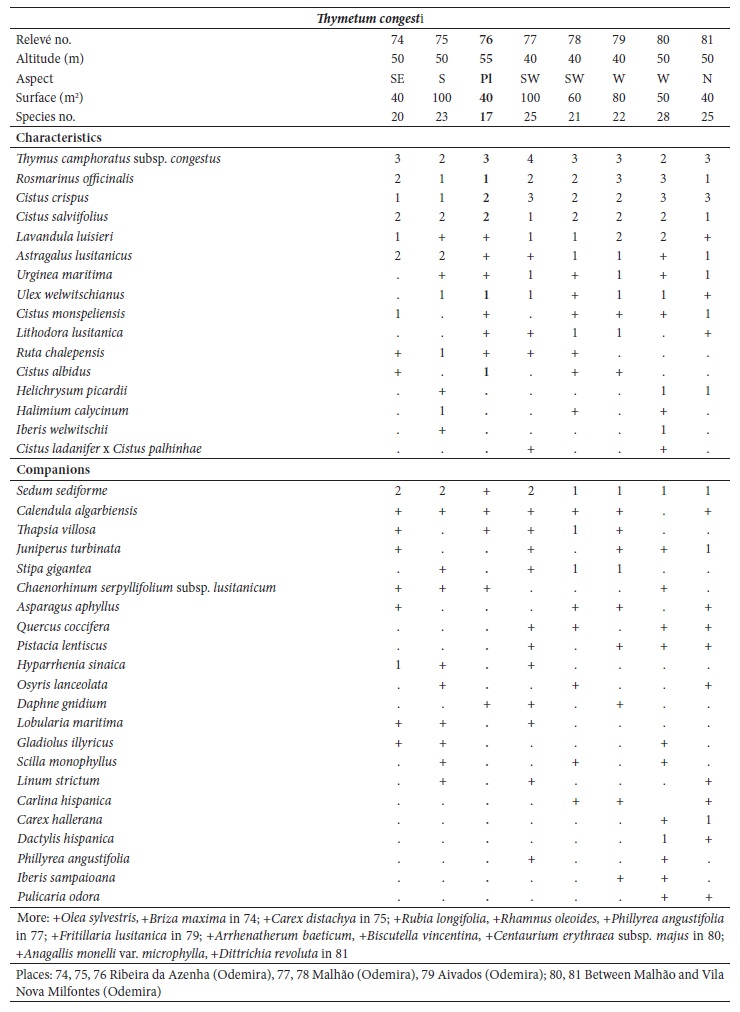

Thymetum congesti J.C. Costa, P. Arsénio, C. Neto, Loidi & P. Gomes in J.C. Costa et al. 2021 ass. nov. (relevés 74-81; Community of Thymus camphoratus subsp. congestusNeto et al., 2009).

(Holotypus: relevé no. 76, table IV in appendix 1)

Pinto-Gomes et al. (2006) described Thymus camphoratus subsp. congestus for coastal alkaline soils areas of Coastal Vincentine district. We found this taxon forming a unique community on lithified calcareous dunes. Thymus camphoratus subsp. congestus is common in the characteristic combination, as well as Rosmarinus officinalis, Cistus crispus, C. salviifolius, C. albidus, C. monspeliensis, Lavandula luisieri, Astragalus lusitanicus, Ulex australis subsp. welwitschianus, Ruta chalepensis, Urginea maritima, and Lithodora lusitanica (table IV in appendix 1). The annual Lusitanian endemisms belonging to Annex II of the Council Directive 92/43/EEC (European Commission, 1992) and the Bern convention (Council of Europe, 1979) Chaenorhinum serpyllifolium subsp. lusitanicum and Jonopsidium acaule are also observed within this association. The occurrence of psammophilous plants such as Halimium calycinum, Iberis welwitschii and Helichrysum picardii is most certainly related to the fact that the substratum rock is barely consolidated, i.e., the limestone cement easily crumbles, producing sand-rich soils. It was mainly observed at Querco cocciferae-Juniperetum turbinatae clearings, with a thermomediterranean, dry bioclimatic belt.

The distribution of Lavandulo luisieri-Cistenion albidi communities in the Iberian Peninsula is presented in figure 4.

IV. Conclusions

In this article we addressed the scrublands occurring in decarbonated, limestone-derived soils, from the west and southwest of the Iberian Peninsula. The analysis presented in this work, comparing these peculiar communities with other communities from Cisto-Lavanduletea, Calluno-Ulicetea and Rosmarinetea officinalis, allowed us not only to increase knowledge on these Iberian communities, but also to improve the syntaxonomical systematization of all these scrublands, paving the foundations for a better recognition in the field, management and conservation of such vegetation patches and the enclosed unique biodiversity.

Syntaxonomical scheme

CISTO-LAVANDULETEA Br.-Bl. in Br.-Bl., Molinier & Wagner 1940

( Lavanduletalia stoechadis Br.-Bl. 1940 em. Rivas-Martínez 1968

( Ulici argentei-Cistion ladaniferi Br.-Bl., P. Silva & Rozeira 1964

(( Ulici argentei-Cistenion ladaniferi

1. Cisto ladaniferi-Ulicetum argentei Br.-Bl., P. Silva & Rozeira 1964

2. Genisto hirsutae-Cistetum ladaniferi Rivas Goday 1955

3. Ulici eriocladi-Cistetum ladaniferi Rivas-Martínez 1979

(( Lavandulo luisieri-Cistenion albidi J.C. Costa, Pinto-Gomes, C. Lopes, Neto, Monteiro-Henriques, Arsénio, V. Silva, Capelo, Lousã & Rivas-Martínez 2021 [new in this study]

4. Lavandulo sampaioanae-Cistetum albidi M.T. Santos in Rivas-Martínez, Lousã, T.E. Díaz, Fernández-González & J.C. Costa 1990

5. Phlomido purpureae-Cistetum albidi Rivas-Martínez, Lousã, T.E. Díaz, Fernández-González & J.C. Costa 1990

6. Ulici airensis-Ericetum scopariae Espírito-Santo, Capelo, Lousã & J.C. Costa in Espírito Santo, Lousã, J.C. Costa & Capelo 2000

7. Anthyllido maurae-Ulicetum jussiaei C. Lopes, J.C. Costa, P. Gomes, Lousã & Ladero in J.C. Costa et al. 2021 [new in this study]

8. Sedo albi-Cistetum crispi J.C. Costa, Neto, P. Gomes, C. Lopes, Monteiro-Henriques, Arsénio, V. Silva, Capelo, Lousã & Rivas-Martínez in J.C. Costa et al. 2021 [new in this study]

9. Thymetum congesti J.C. Costa, P. Arsénio, C. Neto, Loidi & P. Gomes in J.C. Costa et al. 2021 [new in this study]

CALLUNO-ULICETEA Br.-Bl. & Tüxen ex Klika & Hadač 1944

( Ulicetalia minoris Quantin 1935

( Ericion umbellatae Br.-Bl., P. Silva, Rozeira & Fontes 1952 em. Rivas-Martínez 1979

(( Ericenion umbellatae Rivas-Martínez 1979

10. Lavandulo luisieri-Ulicetum jussiaei J.C. Costa, Ladero, T.E. Díaz, M. Lousã, Espírito Santo, Vasconcelos, Monteiro & A. Amor 1993

11. Thymo villosi-Ulicetum airensis J.C. Costa, Capelo, Espírito Santo & Lousã in J.C. Costa, Capelo, Neto, Espírito Santo & Lousã 1997

ROSMARINETEA OFFICINALIS Rivas-Martínez, T.E. Días, F. Prieto, Loidi & Penas 2002

( Rosmarinetalia officinalis Br.-Bl. ex Molinier 1934

( Saturejo-Coridothymion capitati Rivas Goday & Rivas-Martínez 1969

(( Saturejo-Coridothymenion (Rivas Goday & Rivas-Martínez 1969) Rivas-Martínez, Fernández-González & Loidi 1999

12. Thymo lotocephali-Coridothymetum capitatiRivas-Martínez, Lousã, T.E. Díaz, Fernández-González & J.C. Costa 1990

13. Sideritido lusitanicae-Genistetum algarbiensis P. Gomes & P. Ferreira 2005

( Ulici densi-Thymion sylvestris (Capelo, J.C. Costa, Espírito Santo & Lousã 1993) J.C. Costa, Capelo, Lousã, Neto & Rivas-Martínez 2009

14. Salvio sclareoidis-Ulicetum densiRivas-Martínez, Lousã, T.E. Díaz, Fernández-González & J.C. Costa 1990 ex Capelo, J.C. Costa, Lousã & Neto 1992

15. Teucrio capitati-Thymetum sylvestris Espírito Santo & Capelo in Capelo, J.C. Costa, Espírito Santo & Lousã 1992

16. Thymo sylvestris-Ulicetum densi (Capelo, J.C. Costa, Lousã & Neto 1993) J.C. Costa, Capelo, Lousã, Neto & Rivas-Martínez 2009

Author contributions

José Carlos Costa: Conceptualization; Methodology; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - original draft preparation; Writing - review and editing. Carlos Pinto-Gomes: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - original draft preparation. Maria Carmo Lopes: Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - original draft preparation; Writing - review and editing; Visualization; Supervision; Project administration; Funding acquisition. Carlos Neto: Conceptualization; Methodology; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - original draft preparation; Writing - review and editing. Tiago Monteiro-Henriques: Conceptualization; Methodology; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - original draft preparation; Writing - review and editing. Pedro Arsénio: Investigation; Resources; Data curation. Vasco Silva: Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - review and editing; Visualization; Supervision. Jorge Capelo: Investigation; Resources; Data curation. Mário Lousã: Project administration; Funding acquisition. Salvador Rivas-Martínez: Conceptualization; Methodology.