I. Introduction

Fare policies play a pivotal role in promoting equity within public transport systems. However, defining what constitutes equitable pricing is a challenging task due to the inherent conflict between the efficiency and equity goals of public transport. Vulnerable groups, such as low-income earners, the olderly, and informal workers, heavily rely on public transport due to limited financial resources (Lucas, 2012; Manaugh & El-Geneidy, 2012) and are thus particularly sensitive to fare increases. When public transport becomes unaffordable, it can exclude vulnerable individuals from accessing essential services, jobs, educational opportunities, or even areas of leisure (Bocarejo & Oviedo, 2012; Hernandez, 2018). Unaffordable fares can either push individuals out of using public transport or force them to allocate a more significant portion of their income to the same service, and, consequently, reducing their overall mobility and contributing to social exclusion and inequality (El-Geneidy et al., 2016; Willoughby, 2002). Acknowledging the complexity of fare policies, it is crucial to conduct empirical studies that measure the impact of fare policies on different population groups to maximize equity. These policies encompass fare levels, fare structures, and payment methods like prepaid passes or combined tickets, all of which influence users’ choices regarding their daily trips (Brown, 2018; Cervero, 1990; Farber et al., 2014; Martens, 2012). Choices include where, when, and how to travel, or whether to use public transport at all.

Despite the important role of out-of-pocket costs, it should be acknowledged that access to public transport is not solely determined by fares. Instead, it is a multifaceted concept influenced by various factors, including schedules, territorial coverage, network connections, comfort, safety, and time, among others. While this article specifically examines the impact of fares, it is essential to recognize that this is just one aspect of the broader set of factors that collectively shape equitable access to public transport. By narrowing our focus to fare pricing, our study provides a unique and nuanced perspective within the existing equity discourse. This research fits squarely within the growing body of transport literature that explores the differential impacts of transport policies on different social and economic groups (Banister 2008). Furthermore, it recognizes its connection to the framework of the United Nations Organization (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities and Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities. This research is most closely associated with Target 11.2, which strives to “provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all” (United Nations, 2015).

Although the topic of transport equity has been given increasing attention in recent years, assessing it is a complex task, with intangible and difficult to measure effects (Manaugh et al., 2015). There is no consensus on the most appropriate measurement, with studies using methods such as the Gini Coefficient and Lorenz Curves (Bandegani & Akbarzadeh, 2016; Delbosc & Currie, 2011; Rubensson et al., 2020), the Theil Index (Camporeale et al., 2019), and the Palma ratio (Guzman et al., 2018; Herszenhut et al., 2022; Pereira et al., 2017; Silver et al., 2023). Most prior studies measure equity of access, using traditional accessibility measurements that do not account for fare price (Silver et al., 2023). Only a handful of studies have included costs, usually as a generalized cost function or value of time indicator (El-Geneidy et al., 2016; Guzman & Oviedo, 2018; Liu & Kwan, 2020; Ma et al., 2017; Oviedo et al., 2019; Vale, 2020). While some studies have assessed the equity effects of fare structure changes using predicted aggregated ridership, they have not delved into the causal factors at a disaggregated level. Notably, there is a lack of explicit studies linking transport-related expenses with identifying the most excluded groups, a gap this research aims to address. There has also been a relatively limited focus on analyzing reported travel patterns and expenditures relative to actual incomes. It is crucial to consider socioeconomic factors such as age, income, gender, and race, as they can provide valuable insights for policymakers to recognize different affordability levels and price satisfaction levels among various groups (Liu & Kwan, 2020; Lucas et al., 2016).

This study also contributes to the expanding literature that looks at equity and transport policy in the Global South (Bocarejo & Oviedo, 2012; Boisjoly et al., 2020; Guzman & Hessel, 2022; Maia et al., 2016; Pereira, 2019). Rio de Janeiro, in Brazil, shares various characteristics and faces challenges like other large Global South cities, such as high rates of inequality, growing populations, urban sprawl and increasing car use, which has led to more congestion and emissions (Blanco et al., 2018; Hidalgo & Huizenga, 2013). These factors present significant challenges to urban transport planning. Many working poor individuals commute between suburbs and the city center, placing a substantial financial burden on transport-disadvantaged residents in the urban periphery. This geographic disparity stems from various factors, including land development, informal strategies attempting to cater to the unmet needs of marginalized communities, and public-private infrastructure models that enhance connectivity in certain regions while neglecting poorer and less commercially attractive parts of the city, keeping transport conditions in Rio substandard (Motte et al., 2016; Vasconcellos, 2018).

The primary objective of this study is to produce new insights and evidence on how to understand the equity implications of public transport fares, taking Rio de Janeiro as a case study. To do this we address two research questions: (1) who are most burdened by the current fare system; and (2) what impact fare prices have on transport equity. This article is rooted in the recognition that public transport services can either enable or hinder access to everything the city has to offer, from tangible resources to social networks to opportunities or even leisure activities, all of which play pivotal roles in the development of social capital and have the potential to decrease various forms of inequalities. The result of this study is of relevance to planners and researchers wanting to evaluate and understand the social consequences associated with public transport fares.

To answer the posed questions, this article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the existing literature on transport fares and equity. Section 3 introduces the case study, providing details on the public transport system and fare policies and pricing in Rio de Janeiro. Section 4 describes the research design, methods, and results. Section 5 offers a discussion and corresponding conclusions.

II. Literature review

Transport equity encompasses a complex set of associations between transport systems, access both to the network and to key destinations, socioeconomic factors, and the spatial makeup of a territory. Martens et al. (2019) define equity in transport as a just, or “morally proper”, distribution of benefits and burdens across populations or sociodemographic groups. Disparities in society become apparent in how these benefits and burdens are distributed, often resulting in unequal access to mobility (Ohnmacht et al., 2009). Drawing from Rawls' Theory of Justice (1971), where all individuals possess equal moral value, Pereira and Karner (2021) propose that the most effective approach to addressing transport equity concerns is to prioritize the needs of marginalized or excluded groups. This is to ensure that public transport is equitable and accessible to all, addressing the unique challenges faced by vulnerable communities.

In contrast to the extensive literature on transport equity and justice, studies on the specific role of transport fare policies have been relatively limited. Existing studies have mostly focused on the theoretical aspects of transport fares, justice, and social exclusion, with only a few empirical investigations demonstrating their real-world connections. Since there is no overarching consensus on the best way to incorporate user costs or what constitutes a fair fare, many studies have used transport affordability to explore equity issues (Levinson, 2010; Venter, 2011). However, even this is not without issue due to the intricate relationship between expenditure and normative notions of affordability. While the measurement of individual or household transport expenditure is conceptually straightforward, linking expenditure to affordability is more complex. Litman (2013) defines affordability as the ability to pay for access to goods and services through transport whenever necessary, while Fan and Huang (2011) relate transport affordability to the financial stress an individual or household experiences in order to acquire transportation. Evaluating affordability commonly involves estimating the proportion of household income dedicated to public transport, as proposed by Gómez-Lobo (2011). Thus, transport affordability goes beyond strictly financial capability, building a framework that connects fares, sociodemographics, and spatial distribution.

Affordability stands as a distinct objective within transport equity, compelling transport authorities to address the fundamental needs of disadvantaged segments regardless of their financial capabilities (Taylor & Tassiello Norton, 2009). However, challenges arise from the tension between providing high-quality public transport services, keeping fares affordable for disadvantaged groups, and financial constraints (Taylor & Morris, 2015). While government subsidies have been introduced in several Latin American countries to mitigate inequality (Guzman & Hessel, 2022; Guzman & Oviedo, 2018; Rivas et al., 2018), debates exist regarding their equity effects.

Moreover, understanding the factors contributing to (un)affordability and transport disadvantage is crucial. In both the Global North and the Global South, the poorest groups undertake fewer trips in terms of distance and frequency due to financial burdens (Clifton & Lucas, 2004; Ureta, 2008). Thus, increasing public transport fares may disproportionately impact low-income segments of the population (Manaugh et al., 2015) and lead to fare-based exclusion (Church et al., 2000). A similar perspective is echoed in the report by the Social Exclusion Unit (2003), which underscores that the cost of public transport directly influences mobility and accessibility. Other studies focused on Latin American cities have found that low-income groups generally experience lower access to transport services and opportunities (Bocarejo & Oviedo, 2012; Boisjoly et al., 2020; Hernandez, 2018).

Transport literature also points to a strong connection between the notions of social exclusion and urban segregation (Currie et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2018). In urban contexts where poverty and periphery are related, residing farther from the central business district correlates with extended travel distances and travel times, potentially influencing the utilization of public transport (Dávila et al., 2006; Ureta, 2008). Therefore, introducing a spatial element, which encompasses factors like residential location and desired destination, is necessary in order to get a fuller understanding of transport disadvantage (Cameron & Muellbauer, 1998; So et al., 2001). While distance, in itself, is an important factor, time is most frequently used in accessibility measurements since those who travel faster may cover longer distances than those residing closer to their destination that rely on public transport. For this reason, car ownership is another key determinant of transport equity (Farber et al., 2014). Blumenberg and Pierce (2014) found that car ownership correlates with increased employment opportunities and that those with fewer travel alternatives are more susceptible to fare adjustments. Moreover, Cervero (1990) identifies a unique dimension of fare sensitivity among passengers commuting for work purposes. This subset of travelers, often driven by necessity, demonstrates a lower responsiveness to fare changes, thus bearing a greater cost burden with fare increases.

Beyond low-income groups and those without access to a car, transport literature has identified other vulnerable groups that are often disproportionately affected by fare changes. These include the olderly, young individuals, women, single parents, minorities, and people with disabilities (Blumenberg & Waller, 2003; Clifton & Lucas, 2004; Deka, 2004; Delbosc & Currie, 2012; Garrett & Taylor, 2003; Lucas, 2012). Other studies, specifically in the United States and Brazil, have found that race plays a significant role in the ability to access the city (Albergaria et al., 2021; Bittencourt & Giannotti, 2021; Nuworsoo et al., 2009). These groups often confront financial constraints and lack access to high-quality transport services and facilities. These findings underscore the nuanced interplay between transport equity and various socio-economic factors.

III. Case study context

Rio de Janeiro, the second-largest city in Brazil, has a population of over 6 million people and ranks second in terms of GDP (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], 2022a, https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/rj/rio-de-janeiro/panorama). Despite its relative prosperity, the city is marked by significant levels of inequality and substantial fragmentation (IBGE, 2010, http://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/; Ribeiro et al., 2010). This fragmentation can be attributed to various factors, including geographic limitations, a mismatch between the employment center and the spatial distribution of the population (Fernández-Maldonado et al., 2013; Motte et al., 2015), historical policies (Lago, 2015; Molina, 2016), and an uneven supply of public transport services (Boisjoly et al., 2020; Carneiro et al., 2019; Pereira, 2019).

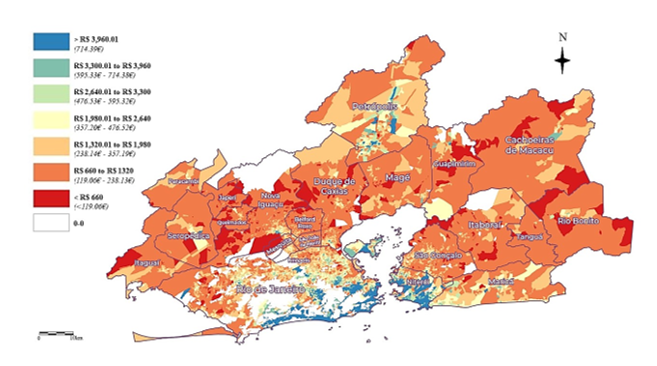

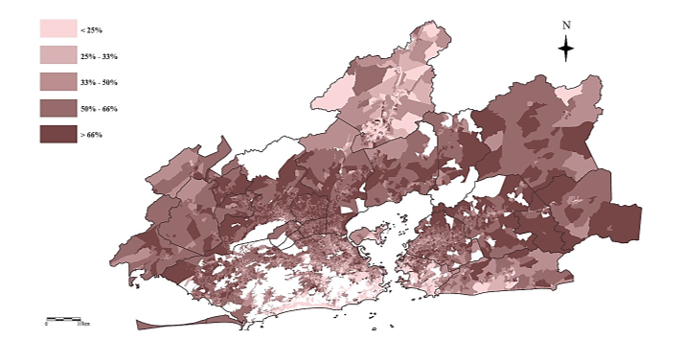

The Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro (RMRJ) consists of 21 municipalities, but the majority of formal job opportunities, approximately 74%, are concentrated within the city of Rio de Janeiro, primarily in the Central Business District (CBD) located in the eastern part of the municipality (Data.Rio, 2023, https://www.data.rio/documents/). This concentration of economic activity in the capital presents numerous challenges for public management, not only concerning urban mobility, but also various aspects of social exclusion (figs. 1 and 2). This spatial dynamic becomes even more pronounced when considering the city's population distribution. Rio's population density is relatively high on a global scale and gradually decreases as one moves westward (Data.Rio, 2023, https://www.data.rio/pages/rio-em-sntese). The city's wealthiest residents typically reside in low-density regions along the southern coastline, and income levels diminish as one moves further north and west away from the city center. The least affluent residents often live in the northernmost or westernmost corners of the city, with some exceptions in the form of favelas (shanty towns), where small pockets of extremely impoverished residents coexist within otherwise wealthier areas. This spatial disparity underscores the complex interplay between economic activity, land prices and social inequality that are the result of typical Brazilian urbanization patterns (Aguirre et al., 2023; Diniz & Vieira, 2016; Nadalin & Igliori, 2015). The economic hub of Rio, centered around the historic city center known as Centro, offers more employment and educational opportunities compared to other parts of the city (Negri, 2010). As a result, a substantial portion of the population, both from municipalities outside Rio and those residing within Rio but distant from the CBD, faces long commutes to access these opportunities (Vignoli, 2008). Due to this spatial configuration, there are large flows of people moving towards the capital.

Unfortunately, public policies have continuously favored motorized transport, specifically the car (Vasconcellos, 2019). This started in the 1950s with the dismantling of the commuter rail system and the implementation of road-based projects. Due to these changes, the bus became the most used form of public transport in the 1950s and has remained so until, accounting for 60% of public transport rideshare (Data.Rio, 2023, https://www.data.rio/). In more recent years, the number of cars and motorcycles exploded. From 2001 to 2015, the number of cars and motorcycles in Rio went from 1.8 million to over 4 million (Diniz & Vieira, 2016). This has brought social costs that are not equally absorbed by the population, but rather, are imposed on the population that is already at a disadvantage due to residing in less accessible areas (Vasconcellos, 2014).

An additional complicating factor is the political overlaps between the different levels of government administration (Vasconcellos, 2018). Political boundaries of local authorities (municipalities) often do not coincide with the functional or economic structure of the metropolitan area. There are further overlaps in the institutional structure, which divides responsibility between state and municipal governments (Pereira, 2019). The state is responsible for rail transport (train and metro), water transport (ferries), as well as intermunicipal buses. The municipalities are responsible for buses (both traditional and BRT) and vans. The municipality of Rio also oversees the the VLT. This creates an environment in which municipal leaders must plan and finance transportation infrastructure in a metropolitan area where state leaders may have their own agendas and infrastructure plans. In response, the Metropolitan Urban Transport Agency (Agência Metropolitana de Transportes Urbanos - AMTU) was established in 2007 as an advisory body linked to the State Department of Transport (Secretaria de Estado de Transportes - SETRANS). Its regulatory framework is defined through an agreement involving the state government and the municipalities in the RMRJ. Despite being among the few entities in the state genuinely dedicated to metropolitan issues, the agency faces challenges due to low institutional capacity, which hinders its effectiveness. By its nature, the agency operates in a consultative capacity and does not possess the authority to regulate metropolitan transport (Instituto de Pesquisa Económica Aplicada [IPEA], 2018). As a result, there continues to be limited coordination between the various planning, regulatory, and operational entities, ultimately penalizing those who rely on the public transport system.

1. Public transport network and pricing

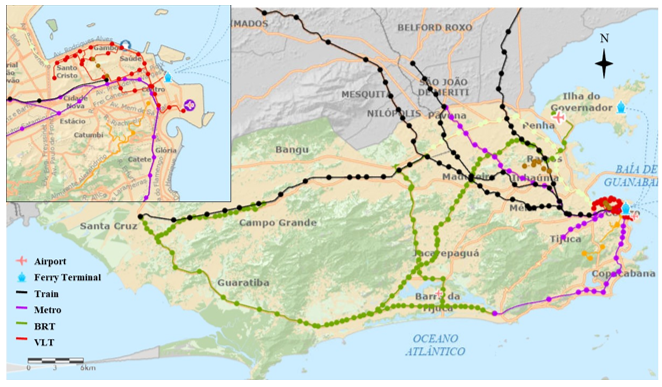

Rio’s formal public transport infrastructure is made up of a metro system, trains, bus rapid transit (BRTs), buses (municipal and intermunicipal), vans, a small light-rail System (VLT), and ferries (fig. 3). The metro system is comprised of three lines that serve primarily middle and upper-class residents, running from the southeast to northeast parts of the city. It is situated wholly within the Rio municipality and has approximately 57kms of track and 41 stations (MetroRio, https://www.metrorio.com.br). Despite the slow expansion and poor network coverage of the Metro, it remains one of the better modes of public transport. The train, on the other hand, serves middle and low-income residents. It connects the CBD to northern and northwestern regions, reaching 11 of the surrounding municipalities. It consists of eight lines, 104 stations and 270km of track (SuperVia, https://www.supervia.com.br). The BRT system cuts across the city, connecting to strategic train and metro stations, and serves a broad range of areas in terms of socio-economic status. The BRT system consists of three lines with 125 stations and 125km of exclusive lanes (Portal Rio 1746, https://www.1746.rio/hc/pt-br).

Transport options also include a small VLT in the city center, a ferry system, municipal vans, intermunicipal buses, and a widely used municipal bus system. The VLT system has three lines and 29 stops, but only serves a small area in Centro (VLT Carioca, https://www.vltrio.com.br/#/). The ferry system has four lines, with the Rio-Niterói line being the busiest route. Municipal vans play a vital role in connecting historically underserved areas to the formal transport system. In the 1990s, “pirate” buses and “kombis” spread rapidly to meet an unmet demand in the periphery and favelas (Rodrigues, 2021). In 2010, the municipal government of Rio began implementing a set of regulations and licensing schemes, but it is estimated that there are still some 8000 illegal vans operating in the city, while only 2000 have been legalized (Balassiano & Alexandre 2013; Regueira, 2021). Municipal buses constitute a significant portion of daily transport, catering to 60% of passengers. They provide a dense network throughout the city, serving as the primary option for low-income residents who do not live near the high-capacity options. Ultimately, buses not only offer wider coverage throughout the city but are also more affordable, especially when considering transfer costs. Consequently, many public transport users opt for buses despite their longer travel times and poor conditions (the average fleet is approximately seven years old and many buses still do not have air conditioning), primarily due to lower fares (Data.Rio, https://www.data.rio/documents/).

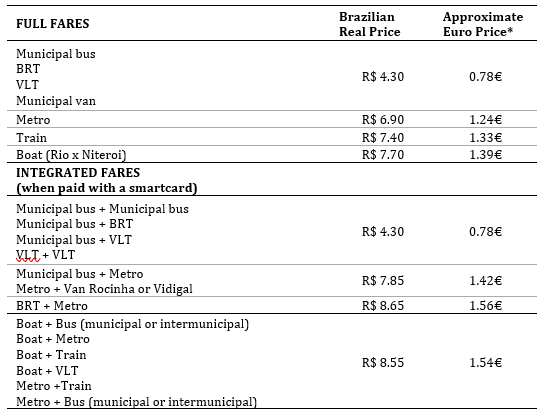

Although buses are priced cheaper than other modes, the faring system is far from straightforward. There are several transport cards (RioCard and Bilhete Único) and overlapping incentives (i.e., gratuities for seniors and students) that offer fare discounts when making a transfer during a single trip, but specific criteria must be met to obtain these cards from having a personal tax identification number, Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas (Registration of Individuals, CPF), to proving monthly income. Rules also vary depending on whether the transfer occurs between municipal modes (i.e. bus to bus) or between state and municipal modes (i.e. metro and bus). These differing fare policies contribute to the complexity of the fare structure (table I).

The combination of Rio's geographic limitations, spatial distribution of low socioeconomic groups and job opportunities, fragmented political structure, uneven supply of transport infrastructure and fare policies resulting in high prices and a complex system, has led to significant transport disadvantage and inequalities within the city. Yet, previous studies on transport equity have often overlooked the role of monetary costs and affordability. This is particularly concerning given that fare structures have a profound impact on the travel behavior of Rio's residents. Transport affordability is a central concern, making it imperative to address how fare prices affect equity within the city.

IV. Data and research design

1. Data

Primary data used in this study comes from a February to March 2023 survey that gathered information on daily travel modes and locations, out-of-pocket costs on public transport, perceptions of the transport system, and demographic information. The survey contained 31 questions and was divided into six sections: the first and second asked for details about the most frequent trip the person made, such as travel mode, motivation for selecting the mode, travel time and trip purpose; the third asked questions about the respondent’s perception of the public transport system; the fourth had questions about transport expenditures; the fifth gathered exact origin and travel destination locations; and finally, the sixth obtained basic socioeconomic characteristics. The survey was open to any adult resident aged 16 and above living in Rio de Janeiro. The online version of the survey was hosted on Google Forms and shared widely through social media. Dissemination techniques included targeted social media advertisements, email campaigns, and sharing in large neighborhood groups that cover general interests and concerns of residents, not specifically transport-related topics. A small number of flyers were handed out at university campuses. In person surveying was conducted at ten transport hubs strategically selected to achieve a spatially diverse sample. Investigators walked around the station and surrounding areas asking if individuals would like to participate. If they agreed, they were given a paper version of the survey and filled it out individually. The investigator was there to answer any questions the respondent may have but did not conduct the survey in an interview fashion. After the respondent was done, generally in about ten minutes, the investigator retrieved the paper and continued. The investigators did not collect data at the same time each day, ensuring representation of respondents across different times, including morning and afternoon, peak and off-peak periods. Both travelers and those working in and around the stations were asked to participate. More than 1000 responses were gathered in total, approximately 75% of which were online and 25% in person, but after a process of refinement, 802 responses were used in this article.

The sample tried to include diverse participants, but it may not reflect the true characteristics of the whole population in terms of demographics or economics. This is likely a result of the snowball sampling method that was conducted mostly online, and therefore, naturally precludes individuals with limited online access, namely the oldest and poorest segments of the population. Despite inherent limitations associated with survey sampling, the sample size is robust and includes respondents with varying ages, races, educational backgrounds, and income levels. While there is always a need for caution when interpreting survey results, using aggregate values mitigates the potential impact of over or under-representation of subgroups. Therefore, while acknowledging this limitation, we argue that the sample still provides valuable insights within the scope of this study.

To answer the questions in section 1 we first described the sample’s sociodemographic attributes by performing exploratory analyses. Next, we defined affordability as it would be used in this study in order to split our sample into two groups to be compared, those who could afford their public transport costs and those that could not. Then, difference-in-difference testing was performed to compare the means of each explanatory variable. These tests allowed us to pinpoint variables that presented statistically significant differences between the two groups. Finally, we used a Pseudo Palma ratio to measure the equity of fare costs across those who could and could not afford their transport.

2. Sample description

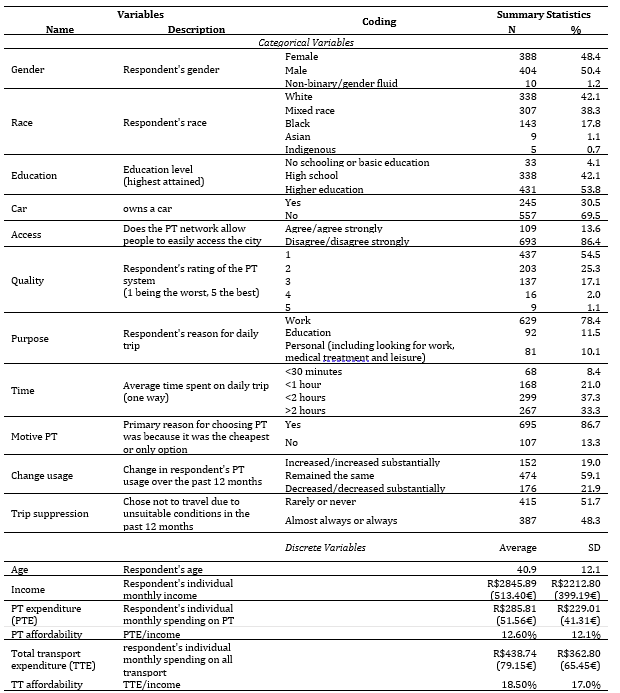

The exploratory analysis provided a description of the sample’s sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, race, education level, age, and income, as well as car ownership, public transport expenditure (PTE), total transport expenditure (TTE), and calculated transport affordability. TTE was calculated by adding reported spending on public transport, costs related to car travel (fuel, tolls, parking), and spending on taxis, moto taxis and on-demand ride-hailing apps like UBER and 99. Additionally, we explored the respondents’ perceptions of public transport (PT), asking how well the network provides access to the city and the overall quality. Finally, we looked at the respondents’ interactions with the PT system, like the motive for selecting PT for their primary daily trip, time spent on their one-way trip, change in PT usage, and whether respondents chose not to travel in the past 12 months due to unsuitable conditions. Full results are in table II.

The sample consists of 50.4% males, 48.4% females, and 1.2% of non-binary or gender fluid individuals; 42.1% of the sample identified as white, while 38.3% identified as mixed race, 17.8% black, 1.1% Asian, and 0.6% indigenous. However, since the late 1970s in Brazil, the concept of Black (“Negro”) has broadened to include both those who self-identify as black (“preto”) and those that identify as mixed race (“pardo”). With this in mind, the majority of the sample, 56.1%, identified with racial categories historically associated with the inclusive term "Negro," highlighting the intricate and fluid nature of racial identity in the country. Only 4.1% of the sample reported no schooling or a grade school level education, while 42.1% of the respondents’ highest level of education was high school and 53.8% had at least some higher education. About 30.5% of the sample owned a car. The average age was 40.9 years old and had an individual income of R$2,845.89 (513.30€). Respondents reported an average PTE of R$285.89 (51.57€) per month and R$438.74 (79.15€) TTE per month. This translates to a sample average of approximately 12.6% of income spent on PT and 18.5% on all transport expenses per month.

While these percentages do not perfectly mirror the demographics in Rio de Janeiro, the sample is broadly representative, especially in terms of age and income. The average age in Rio is 38.8 years old and the average income was R$2,898 (522.80€) in 2021 (IBGE, 2022a, https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/rj/rio-de-janeiro/panorama). Our sample skewed slightly less white than the city as a whole, which was 51.5% white, 36.5% mixed race, 11.6% black, 0.7% Asian, and 0.1% indigenous, according the 2010 Census. Here it should be noted that the survey was open to those living outside of the Rio municipality, which have higher percentages of higher black and mixed race populations (see fig. 2). The largest divergence was in gender representation. Our sample contained just over 50% male respondents, whereas men only make up 46.4% of Rio’s population (Data.Rio, 2023, https://www.data.rio/pages/rio-em-sntese).

Relating to interactions with and perceptions of the PT system, the majority of the sample’s primary daily trip was for work (78.4%). About 11.5% of the sample’s trip was for educational purposes, while the remaining 10.1% traveled for personal reasons that included looking for work, transporting family members, medical treatments, and recreation or leisure activities. Travel times for the sample were high with 33.3% reporting traveling over two hours each direction and 37.3% traveled up to two hours (between one and two hours). Only 8.4% traveled under 30 minutes to get to their destination. Perceptions of the public transport system were very low across the board. On a Likert scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being the worst, 54.5% gave the PT system the lowest possible rating of 1, while only 3.1% evaluated the system positively (rating it 4 or 5). A bit more of 86% of respondents disagreed or disagreed strongly with the statement “the public transport system in Rio de Janeiro allows people to easily access their desired locations”; 47.3% of the sample population said they almost always or always chose not to travel on PT in the past 12 months due to unsuitable conditions, though these could be financial conditions or unsuitable conditions of the PT options, infrastructure, quality, etc. Finally, 86.7% of respondents chose to travel by PT because it was the cheapest or their only option.

3. Affordability

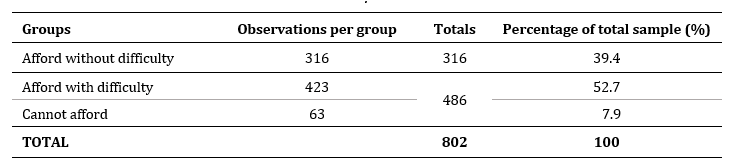

Since affordability measurements can be problematic (Gomez-Lobo, 2011; Zhao & Zhang, 2019), instead of creating a specific threshold of the percentage of income used on public transport, we compare those who say they can afford their daily transport without difficulty against those who say they are able to pay but with difficulty or are unable to pay at all. Since the perception of costs are relative, and there is no universally agreed upon percentage that is deemed “affordable” or “unaffordable” (Venter & Behrens, 2005), we believe that using each respondent´s own account of “affordability” to be the most appropriate benchmark.

However, there is not necessarily a monotonic relationship between transport expenditure and welfare (ibid.) nor between transport expenditure and income (Serebrisky et al. 2009). Due to trip suppression or choosing cheaper, or free, modes like walking and cycling, poor households may spend a smaller proportion of their income on transport. Thus, if not carefully considered, it could seem as if transport affordability is a bigger problem for middle income families (Gomez-Lobe, 2011). There is also substantial evidence to show that poor choose to walk as a means of transport much more than wealthier individuals (Badami, 2009; Cropper & Bhattacharya, 2007), and in Brazil, the poor are heavily dependent on bicycles (Vasconcellos, 2012). In order to avoid wrong conclusions we have opted to look only at those who report using public transport for their primary daily mode of transport, recognizing that this excludes the poorest and richest segments of the population. The poorest are excluded due to the trip suppression or choosing free modes, while the richest are excluded, as wealth and car usage are highly correlated in Rio. The richest segments of the population are simply much less likely to use public transport, with the exception of some metro users (Carneiro et al., 2019). Further, careful oversight was taken when evaluating the respondents who stated they could not afford their daily trip, ensuring that they did report making a daily trip and provided both their transport expenditures per month and their income. Table III shows the breakdown of the sample by affordability groups. Only 39.4% of respondents were able to afford their daily transport needs without difficulty, while 60.6% of the respondents find their public transport costs unaffordable.

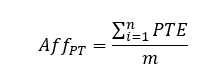

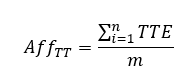

Although we have opted to use reported affordability as the primary metric to split our sample, we also employ a more traditional affordability measurement. The most common approach, according to Gómez-Lobo (2011), is to estimate the public transport expenditure as a proportion of the household income. They define it as seen below in formula I:

Where x m ( P m ,y) are the number of trips taken per month by person 𝑚, and 𝑦 is the household income. Because our sample already has public transport expenditure per month for each respondent, we do not need to calculate an estimated number of trips taken by trip cost. Additionally, because monthly income in our sample is a categorical variable, we use the median amount of each category to stand for individual income. Thus, we use formula II as a supplementary measurement of public transport (PT) affordability:

Where 𝑃𝑇𝐸 is the monthly public transport expenditure of a resident and 𝑚 is the monthly income of that resident. Total transport (TT) affordability was calculated in the same way but using total transport expenditures (TTE), which was the sum of reported monthly spending on public transport, costs related to car travel (fuel, tolls, parking), and money spent on taxis, moto taxis and on-demand ride-hailing platforms. Thus, TT affordability was defined in formula III as:

Although our survey also asked for household transport expenditures and household income, we have opted to use the reported individual amounts. This is because respondents had difficulty knowing how much the entire household spent on transport, but they had much greater certainty when reporting their own transport expenditures. Using these two metrics, reported and calculated affordability, provides a more comprehensive understanding of public transport affordability in the Rio de Janeiro context.

4. Difference-in-difference testing

To measure which groups were most burdened by high fare prices, the sociodemographic features of respondents were related to the reported affordability metric outlined previously. Reported affordability acts as the dependent variable in this study. Since preliminary analyses show that the sample does not follow a normal distribution and homoscedasticity, a requirement for traditional t-testing, the Mann-Whitney U test was utilized to calculate the difference in means of numeric variables. Pearson Chi-square was used for binary variables, and the Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables due to low frequencies in some cells.

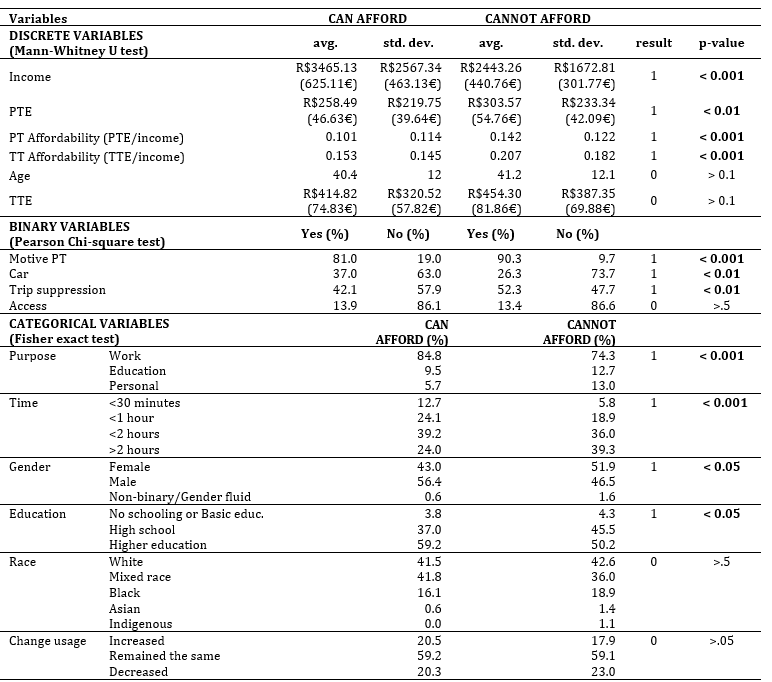

The results, presented in table IV, reveal that income, PTE, as well as calculated PT Affordability and TT Affordability, all present statistically significant differences in the target populations, those who report they can afford transport and those that cannot. Those who report their transport costs were unaffordable had lower incomes and higher PTE. These findings reinforce that respondent´s perception of what is affordable aligns with their real incomes and out-of-pocket costs. Women, those with lower education levels, and those who do not own a car were more likely to report that they could not afford their transport. This observation aligns with other research showing that women in Brazil earned an average of 22% less than men at the end of 2022 (IBGE, 2022b) and were more likely to utilize public transport, even in households that own cars (Goel et al., 2022). The results further support previous studies that found women are more affected by transport fares than men (Silva Montalva, 2022). While our analysis suggests that gender non-binary individuals are also more likely to report affordability concerns, it is important to note that the observed effect should be interpreted with caution. The sample size of gender non-binary individuals in our study is small, and as such, it may not provide a robust basis for drawing definitive conclusions.

Table IV Results of hypothesis test for difference in means.

*Estimates based on average BRL to EUR exchange rate in February 2023: R$ 1 = €0.1804

Results also show that those who cannot afford their transport have much longer commute times, with 39.3% stating they spend more than two hours on their trip. This makes sense since Rio’s fare system only allows one transfer when paying with a RioCard or Bilhete Único card. The second mode is not free, but rather a reduced fare is charged (see table I). For those paying cash, there are no free or reduced-price transfers. Thus, those traveling the furthest distance are more likely to utilize transfers and potentially pay additional fares. Those most burdened by the fare cost are less likely to be traveling due to work (74% vs. 85% of those that can afford transport) and more likely to be traveling for personal reasons, which include medical treatments, looking for work, transporting family members and leisure. Findings indicate that those who cannot afford their transport are more likely to have chosen not to travel in the past 12 months and were more likely to say they chose PT because it was the cheapest or their only option. Again, pointing to those with more ability to pay, having more transport options and being more likely to own a car.

5. Measurement of equity

To answer the second research question, we opted to use the Palma ratio to measure inequality of transport expenditure. Originally created as an alternative to the Gini index to evaluate income inequality, it has seen increased use in transportation literature in recent years (Guzman et al., 2018; Herszenhut et al., 2022; Pereira et al., 2019; Silver et al., 2023). The Palma ratio divides the income share of the richest 10% of a population by the income share of the poorest 40% of the population (Palma, 2011). The justification was that middle-class income almost always accounts for roughly half of national income so it is more telling to compare the extremes. It should be noted that interpreting Palma results is not automatically intuitive since an index value of 0.25 signifies a state of perfect equality. When the index exceeds 0.25 it signifies advantage for the richest 10%, whereas an index below 0.25 indicates advantage for the poorest 40%. Thus, the larger the ratio is, the more inequality. This is in contrast to the Gini index, which assesses the extent to which the distribution of income (or another quantifiable measure of a finite asset) among individuals differs from a state of perfect equality but does not say anything of the socioeconomic status or conditions of those individuals with the highest or lowest income levels.

We build on this principle and adapt the indicator to measure inequality in transport expenditure. This is a more suitable indicator since it reflects how inequality levels are affected by transport costs experienced by the most and least well-off groups. Looking at PTE and TTE, we found high levels of inequality. The poorest 40% are spending four times more on transport relative to their income than the richest 10% of the sample (see table V). These results reinforce the notion that fare policies and transport costs impact equity outcomes. They also suggest that directing policies aimed at fare reduction or targeted transport subsidies could help mitigate transport related inequalities in Rio.

V. Discussion and conclusions

Using Rio de Janeiro as a case study, this study investigated the impact of transport fares on inequality in order to produce new insights on transport affordability and a better understanding of the equity impacts of public transport fares. While the analysis was focused on Rio, it is likely that the results apply to other Latin American cities with similar socioeconomic conditions, spatial segregation, and transport policies are present. Our results reveal 60% of the sample reported that they could not afford their daily transport needs or could not afford them without difficulty and 57% stated they had difficulty paying for the travel needs in the past year. This was reinforced by the calculated affordability, which showed that those who stated they couldn’t afford their transport were spending, on average, 14% of their income on public transport and almost 21% on total transport expenditures. These figures are much higher than any of the various affordability thresholds that have been suggested in the literature (Venter & Behrens, 2005).

Looking at which groups were most burdened by the high fare costs, we found that women, those living far from their primary destination, those who earn less, those with less formal education, and those who do not own a car were most likely to consider their transport costs unaffordable. This is in line with previous research showing that women earn less on average than men and are less likely to own a car. It also reinforces that poverty and periphery are related, double burdening those that live further away from the capital to bear both the time cost and out-of-pocket expense of these longer journeys (Goel et al., 2022; Motte et al., 2016; Paulley et al., 2006). Results also show that those who could not afford their transport costs were more likely to forgo travel, aligning with the findings of Clifton and Lucas (2004). About 52% stated they almost always or always avoided using public transport due to unsuitable conditions, pointing to significant trip suppression.

Understanding passengers’ degree of satisfaction with public transport is also helpful for improving both service quality and fare policies (Nuworsoo et al., 2009). In this article, it was found that more than 50% of respondents rated the quality of PT in Rio as 1 (the lowest rating on a Likert scale of 1 to 5) and the average rating was a 1.7, highlighting the extreme dissatisfaction with the PT system. But, those who could afford their transport and who traveled shorter distances were more satisfied, showing that there is room for improvement. Regardless of income or affordability metrics, 86% of all respondents did not believe that the PT system allows people to easily access the city.

Based on these results policymakers should prioritize reinforcing the public transport options outside of the CBD and the South Zone, which are already well served. Since rail transportation can satisfy the travel demands of the low-income residents and commuters (Gkritza et al., 2011) and even shift travelers away from private car usage (Shen et al., 2016), priority should be placed on improving the train system, which is the only high-capacity option serving the North and Northwest zones, and which is frequently plagued by unforeseen delays, extreme overcrowding, and safety concerns (Albergaria et al., 2019). However, infrastructure improvements alone are not enough and should be taken into consideration in tandem with fare policies.

The train price rose by 48% right before this study was conducted, going from R$5.00 (0.90€) to R$7.40 (1.33€) for a single journey in February 2023. While other modes also increased around the same time, the municipal bus went from R$4.05 (0.73€) to R$4.30 (0.78€) in January 2023, and the Metro increased from R$6.50 (1.17€) to R$6.90 (1.24€) in April 2023, proportionally much smaller price increases (~6.15%). They are more similar to the annual minimum wage readjustment, which was 9%, making the minimum wage as of May 1, 2023, R$1,320 (238€/month) (Presidência da República, 2023). Although prices were raised to alleviate financial strain on operators, it disproportionately impacted low-income groups, who happen to be the most frequent train riders.

Given these circumstances, policymakers should explore alternatives such as implementing graduated fare structures, creating a fare capping mechanism, providing targeted subsidies, or even free fares, something long demanded by transport activists in the city. These measures aim to address the unintended consequence of the steep train fare increase, which may drive more travelers, particularly those from low-income groups, towards cheaper modes of transportation, such as buses. This phenomenon was already occurring before the increase, as bus companies strategically competed with higher-capacity modes by aligning their routes along the rail lines. By adopting more inclusive and nuanced fare policies, policymakers can better balance the financial sustainability of transportation services with the socio-economic well-being of the most vulnerable public transport users.

Relative to the impact of fare prices on equity, results reinforce that pricing policies have a profound impact on inequality. Inequality of transport expenditures in relation to income was very high. Here, it should again be reinforced that our sample population was only those who reported using public transport for their daily travel. This automatically excludes the wealthiest individuals who are highly car dependent in Rio (Pero & Mihessen, 2013). Should the sample have included car users as well, inequality results are likely to be much worse (Farber et al., 2014). Nonetheless, the study provides a detailed analysis of the impact of fare pricing on different socioeconomic groups and subsequent equity outcomes. It is of relevance for those wishing to develop more affordable and equitable public transport systems in Rio de Janeiro and the Global South more generally.