Highlights

Snow cover at Penhas Douradas declined by 5.4 days per decade since the 1950s.

A warming trend of +0.17 °C per decade was recorded from 1883 to 2020.

The snow season now starts one month later and ends one month earlier, with major losses in December, January, and March.

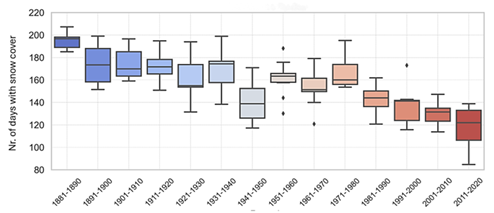

Torre Plateau snow cover dropped from approximately 170 to 120 days per year since the late 19th century.

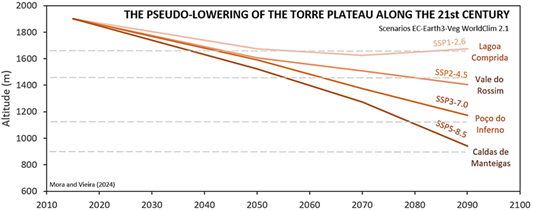

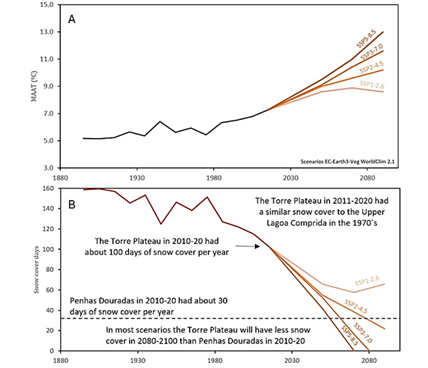

All scenarios except SSP1-2.6 project less snow on Torre Plateau than current levels at Penhas Douradas.

1. Introduction

Snow is a key element of Earth's cryosphere with a major impact on climate at the global level and representing an important natural resource. Snowmelt provides drinking water to approximately 17% of the world’s population and is used for hydropower, agriculture, and industry (Bormann et al., 2018). Despite the limited observational data from mountains, a significant decline in Northern Hemisphere spring snow cover has been reported, with the largest decreases over higher latitudes and in mountain regions, a fact strongly associated to atmospheric warming (Bormann et al., 2018). The amplified effect of the decrease of snow and ice at high latitudes is well-known, but there is growing evidence that the rate of warming is also amplified with elevation and, as such, mountain environments are and will suffer more drastic changes under a warming climate (Pepin et al., 2015).

Changes in the duration, extent, and timing of the onset and melting of snow cover have major impacts in mountains (Liston & Hiemstra, 2011). Modifications on the snow albedo and snow melt also influence energy fluxes and mountains’ local and microclimates (Brun & Pomeroy, 2001). The duration of water storage in the snowpack affects soil moisture and catchment hydrology (Diffenbaugh et al., 2013; Brown, 2019) and impacts water availability for consumption, agriculture, tourism, and hydropower production (Barnett et al., 2005; Bormann et al., 2018). The changes in mountain snow cover also impact the sensitive alpine and sub-alpine ecosystems.

The impacts of climate change on the cryosphere in mountains in warm and dry mid-latitudes, such as the Mediterranean, is highly relevant. These have been shown in several mountain regions where snowmelt is the main component of the surface water resources during the summer, such as the Spanish Sierra Nevada (Perez-Palazón et al., 2018), the eastern Pyrenees (López-Moreno et al., 2009) and the Atlas Mountains (Marchane et al., 2015). Mediterranean mountains show hotspots of high environmental value, such as biosphere reserves with rare endemisms. They host an exceptionally high number of cold-adapted endemic plants and are exposed to a high risk of biodiversity loss due to climate change (Di Musciano et al., 2018; Lamprecht et al., 2021). Species are subject to great stress and need biotic adaptation responses to modifications on climate, such as the decrease of precipitation and the increase of the air temperatures that together give rise to a shortening of the snow cover extent and duration, and ultimately translate to a reduction in summer water availability (Lamprecht et al., 2021).

Increasing variability of precipitation and air temperatures also affect mainland Portugal, as a result of its position in the transition between the Mediterranean basin and the NE Atlantic (Carvalho et al., 2014; Ramos et al., 2011; Soares et al. 2017). Most precipitation in Portugal falls as rain and snow below 1500m occurs only in rare events. Hence, snow cover is confined to the highest mountains of northern and central Portugal. The Serra da Estrela, rising to 1993m above sea level is the range where snow cover lasts for longer, but data allowing for its quantification is scarce and studies are lacking. The Estrela has been traditionally the location in Portugal for snow leisure activities (Andrade et al. 1992; Carvalho 2007), with a small ski resort installed in the plateau between 1850 and 1990m above sea level, which struggles to maintain conditions for ski practice. Until the 1970s, a small ski piste was maintained at approximately 1700m above sea level close to the Penhas da Saúde at Piornos but was then abandoned due to lacking snow. Despite the reduction in snow cover duration, the Serra da Estrela continues to be associated to snow in Portugal, with numerous tourists visiting the upper areas (Silva et al., 2018), which are easily accessible by car on a national road.

The elevation of the Serra da Estrela and geomorphology traits marked by the Pleistocene glaciations, together with a long history of grazing, gave origin to a rich biodiversity. The Estrela plateaus are integrated in a Natural Park, are protected by the Natura2000 network and include a Ramsar site under the Convention on Wetlands, as well as biogenetic reserves. They show the last remnants of alpine and sub-alpine ecosystems in Portugal and are home to several important species, such as the Lacerta monticola in the Red List of the vertebrates of Portugal (Oliveira et al., 2005), several of them depending on the effects of snow cover.

Most direct observations on snow cover in the Estrela plateaus ceased in the mid-1980s and are currently done only at the meteorological station of Penhas Douradas, which at 1380m above sea level is now too low for snow research. The snow and its fate, an issue that crosscuts different environment-related disciplines and socio-economic activities, are central issues for a proper management of this sensitive mountain area, which holds a status of both a Natural Park and a UNESCO Global Geopark (Vieira et al., 2020).

This study aims at filling the gap on understanding the evolution of the snow cover and its spatial distribution in the Serra da Estrela since the late 19th century, as well to provide an outlook on its evolution during the 21st century. Our key objectives are to: i) provide a characterization of the evolution of the snow cover based on observational data from the mid-elevation plateau of Penhas Douradas (1360m asl) since the 1950’s, ii) reconstruct the potential time-series of snow cover for the Penhas Douradas and the upper plateaus of the Serra da Estrela since 1880, and iii) assess the possible futures of the Estrela snow cover and briefly discuss the potential impacts of the expected changes.

To overcome the lack of observational data at high elevation, we analysed the series from the Penhas Douradas observatory, together with remote sensing imagery and climate modelling data. Scarce observational data, coarse-grained re-analysis that poorly represents the upper mountain conditions and a cold season with high cloudiness, limiting the application of multispectral remote sensing, pose significant limitations to the analysis we present here. However, the synergistic exploration of the available data allows for a first insight into the recent evolution and fate of the Estrela snow cover. Given this framework, the results need to be used with special care.

2. Study area

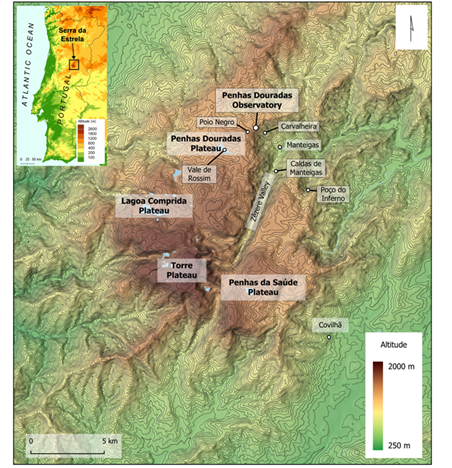

The Serra da Estrela is part of the Iberian Central Cordillera and is the highest mountain in mainland Portugal (fig. 1). Its plateaus that rise between 1400 and 1993m westwards of the Zêzere - Alforfa valleys, and between 1400 and 1750m eastwards, are a key feature of the mountain’s relief, affecting its climate and hydrology. In the Pleistocene cold periods, these plateaus were responsible for fast and extensive glacial inception due to their position just below the equilibrium line altitude (Vieira, 2008; Vieira & Woronko, 2021; Vieira et al., 2021), and they are key to the present-day snow dynamics.

Fig. 1 Relief of the Serra da Estrela and location of sites mentioned in the text. Water bodies represented in blue. Colour figure available online

The mountain massif shows a NNE-SSW orientation and forms a barrier to the prevailing atmospheric circulation that brings moist air masses from the Atlantic into inner Iberia (Mora & Vieira, 2020). The climate is typically Mediterranean, with dry and warm summers and a wet cold semester (Mora, 2010). Daveau et al. (1977) estimated a mean annual precipitation for 1931-60 of 2500mm at the summit of the mountain. Data from the Penhas Douradas shows a precipitation of 1817mm for 1941-1970 decreasing to 1511mm in 1981-2010. Mean annual air temperatures were estimated by Vieira and Mora (1998) to be close to 4°C at the summit in 1941-70.

Andrade et al. (1992) analyzed snow cover data from 1957 to 1985 from three meteorological stations: Penhas Douradas (1380m), Penhas da Saúde (1510m) and Lagoa Comprida (1604m). They showed that snowfall events were more frequent from December to March, but only in February the number of snowfall days surpassed the number of rainfall days, highlighting the warm characteristics of the precipitation, even during the winter.

Snow cover was characterized by large interannual and intermonthly irregularity, and snow cover was more frequent, above 1800m, lasting for several weeks in winter. However, even at that elevation, warm rainy episodes generated extensive snow melting, interrupting the persistence of winter snow cover. The authors reported a median of 26 days with snow cover at 1600m and estimated about 70 days for the Torre plateau.

3. Data and methods

3.1 Introduction

Studies of snow cover in the Serra da Estrela, as well as in other Portuguese mountains have been hampered by the lack of good data-series and absent data from high elevation sites. To characterize the past changes in snow cover we have analyzed monthly precipitation, air temperature and snow cover duration from 1954 to 2019 using data from the Penhas Douradas Observatory, the highest meteorological station in Portugal still operational (fig. 1). To complement these observations and extend the analysis to higher elevations, we analyzed daily MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) optical imagery from 2001 to 2020.

This allowed us to generate a dataset with the presence of snow in different sectors of the plateaus. Besides the observational data, we analyzed modelling datasets and compared them to observations. This was done for the ERA-5 Land reanalysis snow cover product that extends back to 1950 at 9km spatial resolution, as well as for the FSM-WRF Iberian Peninsula dataset at 10km resolution from 1981 to 2014, that models snow thickness for different elevations using the ERA-Interim (Alonso-González et al., 2019). The evolution of the snow cover duration for the upper areas of the Estrela range was estimated by linear regression modelling at decadal intervals using temperature data from the Penhas Douradas, with model results validated for the period with observation data. This allowed us to reconstruct the snow cover duration in the Torre Plateau since the 1890s. The future evolution of the snow cover climate scenarios was assessed using climate change scenarios obtained from WorldClim 2.1 until 2080-2100.

3.2 Data from the Penhas Douradas Meteorological station

The highest meteorological station with a long time-series is located at the Penhas Douradas, an observatory of the Portuguese Institute of the Sea and Atmosphere (IPMA), at 1380m above sea level (fig. 1). Despite its low elevation when compared to the plateaus that range from 1400 to almost 2000m, it is the only high mountain station in Portugal. Thus, its observational data set is crucial for analyzing the snow cover and for validating the remote sensing and modeling data that complement our analysis, enabling insight into the snow cover regimes at higher elevations.

The Penhas Douradas station is located at the top of the Zêzere valley slope, in the upper Manteigas basin at in the northeastern limit of the Penhas Douradas plateau. Surrounded by a Pinus sylvestris forest, the site shows different topographic and vegetation conditions from the rest of the Estrela plateaus at similar elevation, which are wide-open areas mostly dominated by heathland.

Monthly mean air temperatures and precipitation data is available from 1883 to 2020 for the Penhas Douradas, but the data series has several gaps. The station changed location before being definitively installed at the current site in 1938. From 1882 until 1898 it was located at the nearby Poio Negro at 1450m above sea level, while from 1899 to 1903, was moved downslope to Carvalheira at 1216m. Since 1903, the Penhas Douradas station has been at the current location, but until 1938 the instruments were at the roof of the observatory building, before being moved to the ground at the current location. Considering the changes in elevation and the location in the vicinity of the current site, we have corrected the annual average temperatures from 1883 to 1898 and from 1898 to 1903 using a lapse rate of -0.6ºC/100m as estimated by Mora (2006) from a regional network of meteorological stations. At sub-daily time scales and mainly under stable anticyclonic conditions and in the early morning, temperature inversions have been recorded in the Serra da Estrela, especially in valleys and glacial cirques (Mora, 2009, Mora et al., 2001). However, these are not long lasting and have a minimal impact in the annual averages. No corrections were made for the temperatures from 1903 to 1938, neither for the precipitation.

The Penhas Douradas station provides data on the daily snow depth, a series that we have obtained from the IPMA for 1954 to 2019. From it, we calculated the number of days with snow cover by considering the days with more than one cm of snow in the ground. After 2004, the series has many short gaps without observations. These concentrate in weekends or following high snowfall events, a pattern likely due to the fact, that the meteorological observer, which until then lived at the observatory, since 2004 commutes daily to the observatory and in deep snow cannot reach it (oral information).

To address the missing snow cover data in Penhas Douradas from 2004 to 2019, we focused on the period from October to May, when snow can potentially cover the ground for more than one day. This analysis resulted in 1,517 days without observations. We then examined these days to identify those with snow cover using visible MODIS imagery on cloud-free days, along with air temperature and precipitation records:

Periods between observed days without snow, which showed no snow in MODIS imagery or had positive temperatures during cloudy conditions, were classified as snow-free.

Periods of a few days between observed days with snow were classified as snow-covered.

Longer periods that were only preceded or only followed by snow cover were analyzed using MODIS imagery. If the scenes were cloud-covered, half of the period was classified as snow-covered and the other half as snow-free. These periods never exceeded two days and were very rare, accounting for a potential error below 1.6% of all missing data.

This approach resulted in a good-quality dataset for the period with gaps, which was 2004 to 2019.

All trends presented were calculated using the Theil-Sen slope method and the statistical significance evaluated using the Mann-Kendall test.

3.3 Optical remote sensing data

Optical satellite imagery allow for the accurate mapping of snow cover, both using visual analysis of single scenes or by applying multispectral indexes (Rees, 2006). The MODIS Terra and Aqua satellites provide visible daily imagery at a resolution of 250m since 2001. Optical sensors are affected by cloudiness, a very important limiting factor in the Serra da Estrela, where cloudy conditions are frequent during the cold semester. Hence, optical satellite imagery is useful only in clear sky conditions. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellite data may be an alternative (Mora et al., 2017), but long data series of SAR at high resolution, such as Copernicus Sentinel 1 are still lacking, since these have only been active since 2015. Other SAR satellites show either low spatial resolution (passive microwave) or lack continuous acquisitions at the global scale.

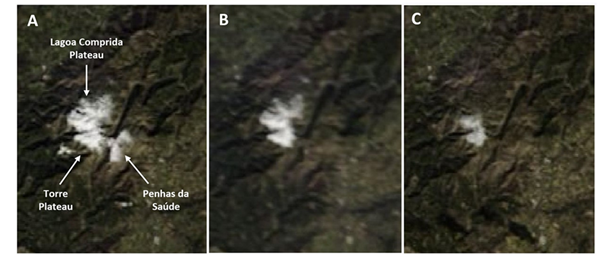

Even though MODIS imagery presents the above-mentioned limitations, it is still the best satellite data to complement the observations from the Penhas Douradas meteorological station from 2001 to 2020, allowing to provide spatial and temporal information about the snow cover regime in the Serra da Estrela plateaus. Hence, in addition to using MODIS to fill data gaps at the Penhas Douradas Observatory series as explained above, we used the daily visible imagery dataset to identify the spatial distribution of snow cover in the Estrela plateaus from 2001 to 2020. The days were classified based on the presence of snow as follows (fig. 2):

Snow present only in the Torre Plateau.

Snow present in the Lagoa Comprida Plateau and above.

Snow present in both the Penhas da Saúde and Lagoa Comprida plateaus and above.

However, the data-series show long periods with cloud cover that limit the ground observations.

Fig. 2 Examples of MODIS RGB composite scenes at 250m resolution for the Serra da Estrela used for snow extent classification: A) Snow cover in the Penhas da Saúde plateau and above; B) Snow cover in the Lagoa Comprida and above; C) Snow cover in the Torre Plateau. Colour figure available online.

These affect 48% of the days and in some cloudy winters, MODIS imagery provides essentially sample glimpes of the snow cover. In order to be able to make best use of the exiting MODIS imagery, we applied the following approach to fill the gaps without data:

If snow cover was observed before and after the cloudy period, all cloud-obscured days were counted as snow-covered. Hence, in these situations, our classification scheme is based on the assumption that in these conditions, the period was fully snow-covered.

If the cloudy period was preceded by a snow-free day and followed by a snow-covered day (or vice versa), the snow-covered days were counted as half the duration of the cloudy period. These periods were very rare and account only for about 3% of cloudy days.

3.4 ERA-5 Land reanalysis data

Reanalysis products generate physically modeled data from multi-source observations from across the world into a global gridded dataset. ERA5-Land covers the period since 1950 at 9km resolution, with its core being the tiled ECMWF Scheme for Surface Exchanges over Land incorporating land surface hydrology (H-TESSEL), using the version CY45R1 of the IFS (Muñoz-Sabater et al., 2021). Despite the coarse spatial resolution and the difficulty to accurately resolve the relief of mountains, such as the Serra da Estrela, the fact that this is a plateau mountain, reduces the terrain complexity. Here, we have evaluated the ERA5-Land data feasibility for the reconstruction of the snow cover and to complement observational datasets.

We have used the snow cover product at 00 UTC, referring to the percentage covered area within the cell within which the coordinate 40.3205ºN, 7.613ºW is located. The number of monthly and annual days with snow cover was classified by counting the days with: i) more than 0%; ii) more than 5%; iii) more than 10% and iv) more than 25% area covered by snow, within the cell. From these, we selected the one better describing the snow cover duration in the Estrela plateaus. This was done by correlation analysis with observational data from the Penhas Douradas observatory (1954-2019) and from the MODIS analysis (2000-2019).

3.5 FSM-WRF Iberian Peninsula snow depth at 10km dataset

Alonso-González et al. (2020) developed the FSM-WRF dataset of daily snow depth and snow water equivalent at 10km resolution for the Iberian Peninsula for 1980-2014. The dataset was produced using the MODIS data for 2000-2014 and a physically based snow model - the Factorial Snow Model (FSM) - driven by the WRF Weather Research and Forecast model. The results were validated using observations from meteorological stations in Spain. Using a k-means clustering, four main types of snow cover regime were shown to characterize the Iberian mountains. The two plateaus of the Serra da Estrela show up as the only areas in Portugal classified as cluster 3, which encompasses mountains with significant snow cover in most cold seasons, but with the possibility of occurrence of years with shallow snowpacks.

The accurate identification of the Estrela plateaus in this regional model led us to evaluate the FSM-WRF dataset to better assess the snow cover characteristics. The dataset provides data for different elevation levels at 100m intervals. We have selected a cell based on a data point at the Alto da Torre and analysed the daily snow-depth data for 1500, 1600, 1700, 1800, 1900 and 2000m above sea level. The series was transformed into daily occurrence of snow using thickness thresholds of >0, >2 and >5 cm, which were compared with data from PD to assess the possibility to use FSM-WRF data for improving the characterization of the Estrela snow cover.

3.6 WorldClim 2.1

WorldClim 2.1 is a global-grided dataset of downscaled climate data for past and future climate. For the past data, the dataset uses interpolation from weather station data using thin-plate splines and covariates such as elevation, distance to the coast, and MODIS-derived maximum and minimum land surface temperatures, as well as cloud cover (Fick & Hijmans, 2017). Mean air temperature, which is the variable we used here, have shown low RMSE values and are accurate, especially in regions with a high density of meteorological stations (Cerasoli et al., 2022; Fick & Hijmans, 2017).

Future scenarios in WorldClim 2.1 have been downscaled from CMIP6 Earth System Models. Here, we have used the EC-Earth3-Veg model (Döscher et al., 2022) mean annual air temperature data for the periods 2040-60, 2060-80 and 2080-2100 at a 30sec grid (c. 1km at the equator). We use the standard socioeconomic pathways (SSP) 1-2.6, 2-4.5, 3-7.0 and 5-8.5. SSP5-8.5 is the so-called fossil-fueled development scenario at the upper end of the warming pathways, with high emissions (Meinshausen et al., 2020; O’Neill et al., 2016). SSP3-7.0 is based on nationalism driving policy and a focus on regional and national problems, rather than on global development. It represents the medium to high end of the range of pathways. SSP2-4.5 is an intermediate scenario, which corresponds approximately to the previous RCP4.5, and includes moderate conditions for land use change and aerosols. SSP1-2.6 represents the low end of the pathways and is a sustainability-based pathway, with policies addressing human well-being, clean energy, and nature conservation. It represents values below 2ºC warming at 2100 as compared to pre-industrial levels (O’Neill et al., 2016). The data was collected from the bioclimatic variables data set of WorldClim 2.1. However, ssp370 for 2041-2060 and ssp245 for 2081-2100 had missing data. Hence, for those two scenarios, we used the climate variables to average the mean temperatures from the monthly maxima and minima.

4. Results

4.1 Climate and snow cover evolution in the Penhas Douradas Observatory

4.1.1 Air temperature and precipitation in Penhas Douradas from 1883 to 2020

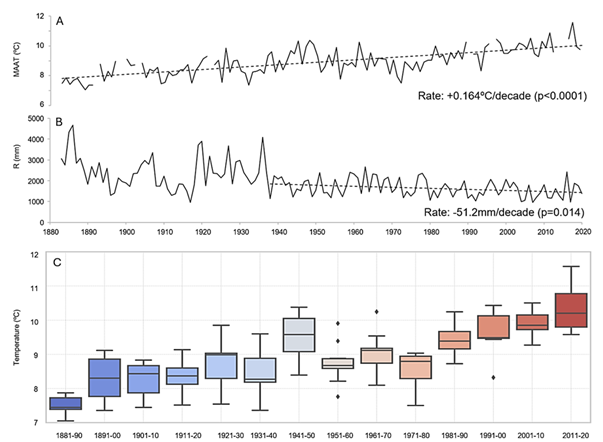

A clear warming trend is present in the mean annual air temperature (MAAT) in the Penhas Douradas meteorological station for the last circa 140 years (1883 to 2020) (fig. 3). MAATs in the early 1900’s were around +8.6ºC and in 2019 were close to +10.6ºC. Despite the trend, three periods can be distinguished. From 1883 until around 1949 the temperatures increased, with the warmest period being between 1945 and 1949. The following three decades were dominated by a cooling trend that lasted until around 1972. MAATs in the 1970’s were close to those of the 1920’s, but since then temperatures started to increase at fast pace, until they peaked at 11.6ºC in 2017. The warming trend from 1883 to 2020 in the Penhas Douradas was +0.164ºC/decade with a p-value <0.0001.

Fig. 3 (A) Mean annual temperature, (B) total annual precipitation, and (C) Mean annual air temperatures (MAAT) per decade in the Penhas Douradas meteorological station from 1884 to 2020 (MAAT corrected for site changes of the observatory before 1938). Colour figure available online.

The decadal data evidences the period of 1941-50 as anomalously warm, interrupting a series that otherwise would have been stable to slightly warming from the beginning of the 20th century until 1971-80 (fig. 3). Since 1981-90, all the decades are warmer than the previous and the warming rate is steeper.

The precipitation regime needs to be analyzed with care, especially before 1938 due to the changes in location in the Penhas Douradas observatory before that year. The data shows high interannual variability, with a decrease in annual totals. Precipitation values averaged c. 2300mm in 1920-40, c. 2000mm in 1941-50 and continued decreasing until around 1600 to 1400mm since the 1980s. However, the high values before 1938 are possibly biased due to changes in station location, with the trend since then being of -51.16mm/decade with a p-value of 0.014.

4.1.2. Snow cover in Penhas Douradas from 1954 to 2020

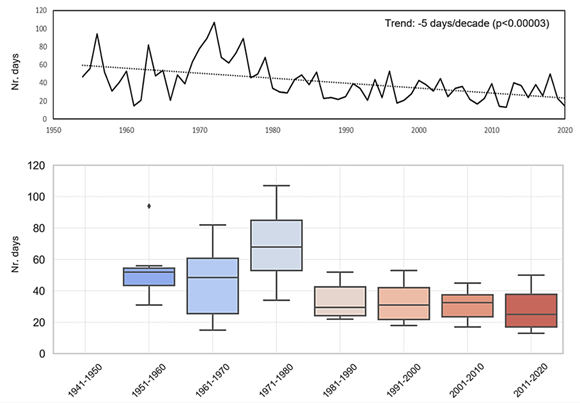

Penhas Douradas is the only meteorological observatory at high elevation in Portugal with a long data-series for snow cover. The data from 1954 to 2020 shows a very strong reduction in snow cover, with a trend of -5 days/decade (at p<0.00003), from an average of 53 days in 1951-1960 to 28 Days in 2011-2020 (table I). The data shows a period with longer duration of snow cover from 1969 to 1976, which is reflected in a peak with an average of 68.6 days in 1971-1980. A sharp change occurred in the following decade, with a strong reduction to an average of 34 days in 1981-1990. Since then, the reduction rate was slower at -2 days/decade, with some years in the early 2000s and in the mid of the decade of 2011-2020 showing longer snow cover (fig. 4).

Table I Mean annual air temperature and mean annual snow cover days per decade in the Penhas Douradas, from 1951 to 2020.

| Mean annual air temperature (ºC) | Number of days with snow cover | |

|---|---|---|

| 1951-60 | 8.8 | 53.3 |

| 1961-70 | 9.1 | 47.0 |

| 1971-80 | 8.6 | 68.6 |

| 1981-90 | 9.5 | 33.6 |

| 1991-00 | 9.6 | 32.5 |

| 2001-10 | 9.9 | 31.0 |

| 2011-20 | 10.4 | 28.0 |

Source: Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, with data estimated for snow cover after 2004

Fig. 4 Number of days with snow cover at Penhas Douradas meteorological station from 1954 to 2020. Upper graph: annual values. Lower graph: decadal box-plots with D1, Q1, Median, Q3 and D9. Colour figure available online. Source: Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, modified after 2004

4.1.3 Seasonal changes in snow cover

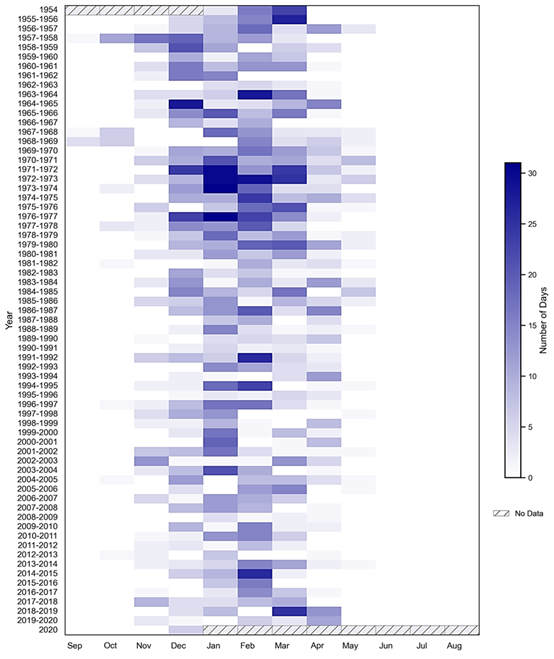

Besides the reduction trend in the number of days with snow cover at Penhas Douradas, the monthly distribution has also changed since 1954 (fig. 5). September and October have always been months of very scarce snow, but while until the late 1960’s snow cover occurred for a few days per year in September, it disappeared after that.

Fig. 5 Number of days with snow cover in the Penhas Douradas Observatory from 1954 to 2020. Colour figure available online.Source: Instituto Português do Mar e Atmosfera, corrected in the period 2004-2020

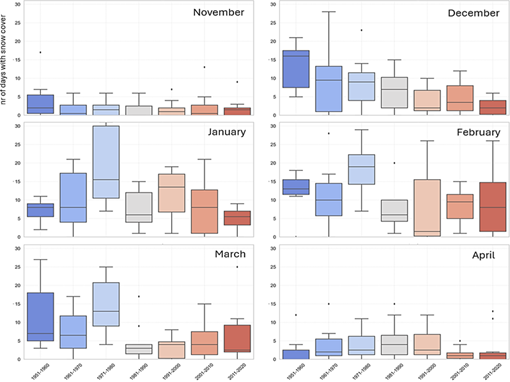

October frequently recorded a few days of snow cover in the beginning of the series, but after the 1980s became a month with very rare occurrences, starting to mirror the characteristics of September at the beginning of the 1950s (fig. 5). These are two months with still warm ground and sporadic snowfall events. November had always a small number of days with snow cover (decadal averages from 1.5 to 4.4 days) and high interannual irregularity. No trend for this month is visible, meaning that sporadic snow events continued to occur during the whole period, but that snow did not last for more than a few days, independently of the year (fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Decadal variability of days with snow cover for the cold season months in the Penhas Douradas Observatory. Decadal box-plots with D1, Q1, Median, Q3 and D9. Colour figure available online. Source: Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, modified after 2004

December showed marked changes in the 1950’s, with two distinct periods (fig. 5). Until the mid-1970s, the ground was frequently snow-covered for about two weeks, but after that, the snow cover showed very short duration lasting only for a few days each year. This became clearer after 1980 and resulted in a remarkable reduction of the snow during that month (fig. 6).

January has been a very irregular month and is characterized by its interannual irregularity (fig. 6), having recorded full snow cover in 1971/72 to 1973/74 (fig. 5). In the last two decades, it became more irregular and even lacked snow cover in some years after 2000. In the second decade of the 21st century January recorded a regime comparable to December in the late 1970s. February, similar to January was marked by high irregularity, but since 2002 it clearly became the month with more snow cover (figs. 5 and 6).

March was a very irregular month, influenced by sporadic snowfall events. Its general behavior during the period is comparable to December, reflecting the strong reduction of the snow cover in the shoulder seasons (fig. 5). However, March reflects a much stronger reduction in snow cover after the 1980's, than any other month (fig. 6).

April has been a month of sporadic snow and despite the general reduction, its behavior is very irregular (fig. 5), depending on the advection regime of spring cold and wet air masses. It seems to be losing its original characteristics to March (fig. 6). May has been typically a month with little snow, peaking in the cold early 1970s, but with negligible snow cover days before and after (fig. 5). April in the 2010s became comparable to May in the 1970s, which may mean a fast shift towards a Mayification of April. The warm season, lasting from June to September is a regular period without snow cover in the Penhas Douradas.

In synthesis, the Penhas Douradas snow cover regime has been marked since the mid-20th century by an increasing interannual irregularity and by a shortening of the snow period. Snow cover at the observatory only approached what could be called a seasonal snow cover from 1971 to 1974, but otherwise, snow rarely covered the ground for over a month in a row. The cold period of the early 1970s is remarkable on its effects on the duration of snow cover, but overall, a trend for a strongly decreasing snow cover is clear during the whole time-series. The season with snow on the ground starts about one month later and ends one month earlier. November and April, show small reduction trends, with December, March and January being the months showing larger reduction in snow cover duration.

4.2 Attempting to evaluate the recent evolution of snow cover from satellite imagery (2001-2020)

The analysis of the MODIS optical imagery at 1-day intervals and 250m spatial resolution allowed insight on the snow cover duration at the plateaus of the Serra da Estrela from 2001 to 2020. This is currently the best option for reconstructing the spatial extent of snow in the Estrela plateaus, but it is an approach that is based on continuity assumptions during cloudy periods, which implies that it needs to be used with extreme care, since cloudy days are very frequent in the cold season.

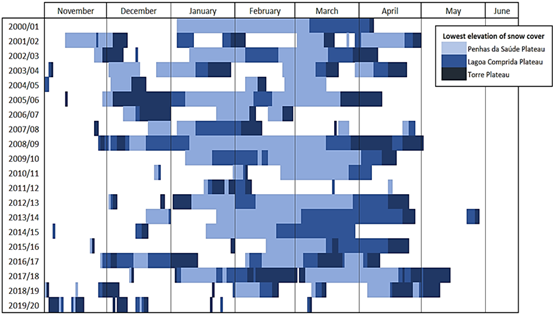

Figure 7 represents the reconstructed days with snow cover at least down to the Penhas da Saúde Plateau (circa 1500m), down to the Lagoa Comprida - upper Penhas Douradas Plateau (circa 1600m) and the days with snow only in the Torre Plateau (circa 1800 m). Similarly to what has been observed in the Penhas Douradas at 1360m, the observations show the high interannual irregularity of the snow cover. In some years, the Torre plateau showed continuous snow cover for several months, such as 2008/09 with snow from late November to early May, or 2005/06 with snow from late November to mid-April. However, in several years, especially towards the end of the series, as in the winters of 2011/12 and 2019/20, snow lasted for only a few days even at upper areas of the Estrela.

Fig. 7 Reconstructed snow cover in the Serra da Estrela plateaus (from MODIS imagery analysis, 2001-2020). Colour figure available online.

The observations show a trend for shorter snow seasons, a significant delay in the onset of snow cover and for less days of snow at lower elevations, as well as a regime where years with seasonal snow alternate with years with sporadid snow, even at the Torre Plateau (fig. 7). While the Torre Plateau may have snow cover at the beginning of the cold season, snow lasting for several days down to Penhas da Saúde before mid-January almost ceased to occur in the last decade.

Typically, longer lasting snow cover starts from higher to lower elevation, but with the delaying of the snow onset to January-February, several years showed an abrupt initiation of multi-day snow cover at all elevations above 1500m. This may be also related with the warmer ground until later in the cold season, limiting snow accumulation or by later and scarcer snow events. The end of the snow period was generally more gradual and started from lower to higher elevation. Snow did not last long at the Penhas da Saúde plateau after mid-March, especially in the last decade. In April, snow cover was frequent only in the Torre Plateau, but in some years, it extended down to Lagoa Comprida.

In rare years, April has shown snow down to Penhas da Saúde for several days, but these have been mainly years of late snow occurrence and probably marked by cold snow events, with snow cover benefiting from the cooler ground from a preceding snow-free period. May showed very rare snow cover. The data clearly shows that despite the delay in the onset of the snow cover, the start of the snow-free period did not change and concentrates in April. The period 2011-2020 has shown more snow in April than the preceding decade.

4.3 Evaluation of climate models for reconstructing the snow cover

4.3.1 Snow cover reconstruction from ERA5-Land

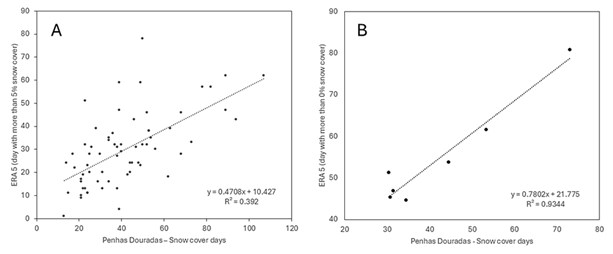

ERA5-Land provides meteorological data since 1950 for a global grid with 9km resolution. Here we evaluate its application to the Serra da Estrela by comparing ERA5-Land data with observations from the Penhas Douradas and with the MODIS snow cover series retrieved for the plateaus. From the ERA5-Land, we calculated the annual days with snow cover for different limits of snow-covered area within the grid point: >0, >1, >5, >10 and >25% area. The comparison of the resulting series with the number of days with snow cover at Penhas Douradas resulted in r from 0.57 to 0.63, significant at p<0.05 (table II and fig. 8A). Correlations with the MODIS series for the Torre Plateau are worst (0.32 to 0.41), but still statistically significant.

Table II Correlations (r) between the number of days with snow cover at Penhas Douradas and at the Torre Plateau, with the ERA5-Land days with snow cover above different area thresholds (>0%, >1%, >5%, 10% and >25%), using annual days and mean annual days per decade.

| ERA5-Land Snow Cover days (area) | Penhas Douradas days with snow cover (Observations) | Torre Plateau days with snow cover (MODIS) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual | Decadal | Annual | |

| >0% | 0.57 | 0.97 | 0.41 |

| >1% | 0.62 | 0.96 | 0.37 |

| >5% | 0.63 | 0.93 | 0.33 |

| >10% | 0.61 | 0.92 | 0.33 |

| >25% | 0.59 | 0.91 | 0.32 |

Fig. 8 Correlations between ERA5-Land of snow cover days and observations from the Penhas Douradas Observatory. (A) ERA5-Land days with more than 5% area of snow cover (annual totals). (B) ERA5-Land days with more than 0% area of snow cover (decadal averages).

The analysis of the decadal means is useful for evaluating long-term scenarios. The comparison of ERA5-Land snow cover days for the Serra da Estrela with the snow cover days at the Penhas Douradas observatory resulted in very strong positive correlations from 0.91 to 0.97 (table II), while the data for the Torre Plateau did not provide statistically significant results. The MODIS results cannot be used for the decades since the series started only in 2000.

Figure 8B shows the example of the correlations between ERA5 Land days with snow presence at the grid and the observations from Penhas Douradas. It is, however, important to notice that the high correlations may be a result of the overall control of mean annual air temperature on the snow cover duration, rather than of the real performance of ERA5-Land in modeling the snow cover dynamics. Actually, as we show below, at the decadal level, colder periods have resulted clearly in longer-lasting snow cover.

4.3.2 FSM-WRF Modeled snow cover duration (1980-2014)

The FSM-WRF modeled snow cover thickness is a dataset gridded at 10 km resolution for the Iberian Peninsula from 1981 to 2014, for 100m elevation intervals, from which we calculated the number of days with over 0, 2 and 5cm of snow depth. We assessed the series performance for the Serra da Estrela from 1500 to 2000m elevation by comparing it with the Penhas Douradas observations and with the MODIS-derived dataset. Statistically significant correlations at p<0.05 were found for elevations above 1900m, but not for all variables (table III). The best correlations were obtained for the Torre Plateau snow cover from MODIS, with a correlation of 0.79 for days over five cm of snow (fig. 9). The decadal means are not analyzed due to the short time-series of the FSM-WRF.

Table III Correlation (r) between the observed number of days with snow cover in Penhas Douradas (PD_Snow), Torre Plateau (TSnowRS), above the Lagoa Comprida (PTSnowRS) and above the Penhas da Saúde Plateau (PSSnow_RS), with the number of days with snow depth (SD) above 0, 2 and 5cm at 2000 and 1900m, from the FSM-WRF model (1981-2019). Correlations at p<0.05 in bold.

| SD FSM-WRF | PD_Snow | TSnowRS | PTSnow_RS | PSSnow_RS |

| > 0 cm (2000 m) | 0.32 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.47 |

| > 2 cm (2000 m) | 0.40 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.59 |

| > 5 cm (2000 m) | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.61 |

| > 0 cm (1900 m) | 0.22 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 0.42 |

| > 2 cm (1900 m) | 0.16 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.43 |

| > 5 cm (1900 m) | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.38 |

4.3.3 Modeling snow cover duration at Penhas Douradas

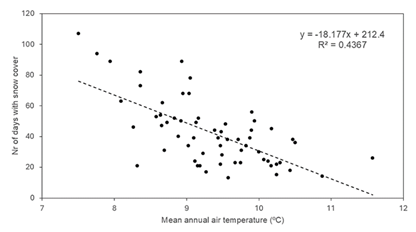

a) Mean annual air temperature and snow cover

The correlation of the mean annual air temperatures (MAAT) with the number of days with snow cover in the Penhas Douradas shows a r of -0.66 at p<0.05, reveals both the control of air temperature on snowfall, but also on melting (fig. 9). Based on this correlation, we approach reconstructing the Estrela snow cover series along the 20th century. This implies the assumption of a similar climatic regime during the period of analysis, especially on the seasonality of precipitation. Since observational and model data show that precipitation has been decreasing and temperature increasing during last century (fig. 3), our approach is based on the broad assumption that present conditions of higher temperature and lower precipitation at high elevation, may be comparable with past conditions at lower elevations.

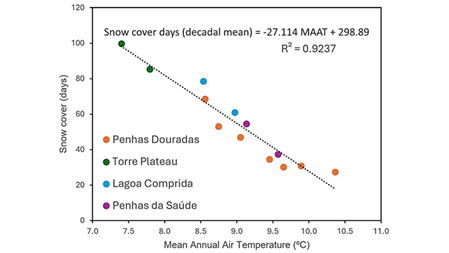

To improve the statistical significance, we reconstructed long-term snow cover trends using the correlation of the decadal averages of the MAAT and snow cover. For Penhas Douradas, the time series from 1955 to 2019 was used, but the values are constrained by the low elevation of the site, not showing large numbers of days with snow nor very low MAAT. To overcome this problem, we have included in the regression observations from days with snow cover from the MODIS reconstruction for the decades of 2001-2010 and 2011-2020, paired with extrapolated MAAT for the Torre Plateau (1800 m), Lagoa Comprida (1600m) and Penhas da Saúde (1500m).

This allowed for better constraining of the best-fit line (fig. 10), resulting in a r value of -0.97 at p<0.05, allowing for high confidence in the application of the equation: Snow cover days (decadal mean) = -27.114 MAAT + 298.89 (Eq. 1). The plateau-dominated relief and smooth summit surfaces of the Serra da Estrela favor the applicability of this elevation-based model, but it is important to note that small topographical effects that depend on slope and aspect are not resolved with this approach.

Fig. 9 Mean annual air temperature and number of days of snow cover at the Penhas Observatory from 1954 to 2020. Colour figure available online. Source: Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, modificado a partir de 2004

Fig. 10 Correlation between the decadal mean annual air temperatures and days with snow cover based on observational data from the Penhas Douradas for 1954-2019, and on MODIS reconstructed snow cover and extrapolated decadal mean annual temperatures for 1500, 1600 and 1800m for 2001-2020. Colour figure available online.

b) Reconstruction of the snow cover duration at the Alto da Torre

We used the mean annual air temperatures for the Alto da Torre at 1993m asl estimated at the decadal level to reconstruct the number of days with snow since 1883 (fig. 11). Although the results need to be examined with care, they allow for insight into the likely evolution of the snow cover duration in the upper reaches of the Serra da Estrela. Following atmospheric warming, snow cover duration has been decreasing from around 170 days in the late 19th century, to about 160 days from 1951 to 1980, and sharply declined to an average of about 120 days in the last decade. The last decade also showed increased irregularity with some winters showing barely any snow cover, which according to the estimations, had never occurred since 1884. The decade of 1941-50 showed anomalously low snow, while the cold 1970s showed values like those of the first half of the 20th century. The model shows a reduction of almost two months in snow cover duration in the Alto da Torre since the late 19th century (fig. 11).

4.3.4 Snow cover at the end of the 21st Century

The projection of the mean annual air temperatures for the Torre Plateau (1900m asl) until 2100 on the EC-Earth3-Veg under different socioeconomic pathways and WorldClim 2.1, shows very high warming (fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Modeled decadal averaged mean annual air temperatures (A) and mean days with snow cover (B) at the Torre Plateau (1900m) from 1880 to 2020 and scenarios following different Standard Socioeconomical Pathways until 2100. The scenarios are 20-year means from the EC-Earth3-Veg (WorldClim2.1). Colour figure available online.

Temperatures at the end of the century may reach around 13 ºC under ssp5-8.5, 11.6ºC under ssp3-7.0, 10.2ºC under ssp2-4.5 and 8.6ºC under ssp1-2.6, being only in the latter that a slight cooling is expected to start in 2080-2100.

Accounting for the assumptions presented above and for the limitations in the modeling, the past and future evolution of the snow cover days for the Torre Plateau can be estimated using Equation 1. The results show that the number of snow cover days at the Torre Plateau will be 0 around 2070 under ssp5-8.5 and 10 years later under ssp3-7.0 (fig. 12). Ssp2-4.5 shows about 20 days of snow by the end of the century, a value below today’s Penhas Douradas, while ssp1-2.6 shows a stabilization at around 60 days of snow cover, which is a reduction to almost half of present-day’s values, even in the best climate scenario.

Discussion

5.1 The evolution of snow cover in the Penhas Douradas since the 1954

Snow cover since the mid-20th century in the Penhas Douradas station at 1380m shows a clear declining trend of c. 5.4 days/decade, with a peak in the late 1960s to early 1970s. The records show change in average number of days with snow cover from 53 days in 1951-1960 to 28 days in 2011-2020. Similar reductions in snow are widespread in other mountain regions in Europe and the World (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2019) and follow the atmospheric warming that has been occurring since the industrial revolution (Carvalho et al., 2014, Ramos et al., 2011, Soares et al., 2017).

Since the 1980s, the decline in snow cover duration has occurred at a slower pace in the Penhas Douradas, despite the continued warming. This seemingly relates to the elevation of the observatory being just high enough to record snowfall in cold meteorological events, but not high enough to maintain the snow in the ground for longer periods. The 1980s seem to have been the transition decade to these new conditions, where snow lasting for several weeks ceased to occur. This hypothesis needs to be further tested by analyzing the events with snowfall and the changes in synoptic conditions causing them. On the other hand, the reduction in snow cover days in December and January, may also be controlled by the warmer ground temperatures in late Fall and early Winter, not allowing for snow to be maintained before, with snow onset moving towards February.

5.2 The evolution of snow cover in Serra da Estrela since the late 19th century

Most of the area of the Serra da Estrela plateaus is above the Penhas Douradas Observatory and lacks observational data, while those are also the areas where snow is more relevant for the ecosystems and as a natural resource. The lack of observations in the plateaus is a major issue that has been seriously affecting the assessment of the impacts of the changing snow cover in the Estrela. Here, we tried to exploit data available, by using data from the Penhas Douradas observatory, from remote sensing imagery and from reanalysis. However, the joint use of these sources for the reconstruction of the snow cover duration time-series was constrained by the low elevation of the observatory, by the short time-series of remote sensing imagery and by problems with clouds affecting the optical imagery.

Furthermore, the reanalysis-based models showed limited ability for accurately resolving the topography of the Estrela. The comparison of observations from the Penhas Douradas with remote sensing imagery and reanalysis data at the monthly and annual levels, showed limitations, which were only solved using decadal averages to reconstruct the snow, cover duration time-series. The interannual variability was lost, but we were able to capture the overall signal associated with the changing climate conditions. As such, the reconstructions that we present here are supported by the decadal correlation between the snow cover duration and mean annual air temperatures and allow a first insight into the recent evolution of the snow cover in the Estrela.

The reconstructed time-series for the days with snow cover in the Torre Plateau show 170 days in the late 19th century, which changed to about 160 days from 1951 to 1980, and sharply declined to an average of about 120 days in the last decade. Interannual variability has increased significantly, with more years with scarce snow towards the end of the period. Lautensach (1929) refering to oral information from the meteorological observer of the Penhas Douradas Observatory, indicated that snow in the Torre Plateau lasted for about 8.5 months, from mid-October to late June, while in Penhas Douradas it lasted for about five months. It is not clear if these values referred to a continuous snowpack, or rather to isolated snow patches. Our reconstruction is more conservative, which suggests that Lautensach’s information may relate to presence of snow patches.

The general warming in the Estrela has led to a shortening and a delay of the snow cover season even at the Torre plateau, where MODIS-derived observations for the last two decades show a cold semester marked by irregularity in snow conditions. While some years show snow from December to April, most years show sporadic snow with snow-free periods even in mid-winter at the Torre Plateau. Extreme years like 2018/19 have almost entirely lacked snow cover. If we compare the snow cover in the Alto da Torre in 2011-2020 with the conditions in the 1970s, the current conditions are close to those of the upper Lagoa Comprida area (at c.1700m) then, which gives a good approximation of the magnitude of the changes that have occurred.

Similar to the Serra da Estrela, a decrease of snow cover has been recorded in other Iberian mountains during the second half of the 20th and early 21st centuries (Bonsoms et al., 2021; López-Moreno, 2005; López-Moreno et al., 2020). Annual and winter precipitation in the Iberian Peninsula between 1961 and 2011 decreased at a rate of 18.7mm/decade (Vicente-Serrano et al., 2017), with snowfall days in the the northern Iberian Peninsula having recorded a 50% decrease since the mid-1970s (Lopez-Moreno et al., 2020; Pons et al., 2010;). The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) has been identified as the main driver of precipitation in Iberian Peninsula in winter, as well as of snowfall in the western and central Pyrenees (López-Moreno, 2005; Revuelto et al., 2012). The predominance of NAO positive phases in winter over the 20th century has lead to a reduction of weather types associated with precipitation (Bonsoms et al., 2021; López-Bustins et al., 2008).

Further south, in the Atlas mountain range in North Africa the large interannual variability of winter precipitation (400%) is affecting the mass balance of the snowpack. The disappearance of many perennial snowpatches in the last decades reflects the warming trend of summer air temperatures since the 1970s (Hughes et al., 2020).

5.3 The fate of the Serra da Estrela snow cover

Our estimates of the evolution of the duration of snow cover for the 21st century show drastic changes occurring at fast pace. All scenarios, except ssp126 place the Torre Plateau before the end of the century with less snow than today’s Penhas Douradas (fig. 12). This means that the Serra da Estrela will clearly enter a sporadic snow cover regime, which will result in dramatic changes in the high elevation ecosystems. However, even at the short-term, almost all scenarios show the snow cover duration in 2030-2040 to become about half that recorded in the early 1970’s, which calls for urgent actions in the management of the plateaus.

Snow reduction scenarios are also foreseen in other mountain ranges in Iberia. For example, Pérez-Palazón et al. (2018) modeled snowfall for the end of the century for the Sierra Nevada and found a decreasing trend in snowfall from 0.21 to 0.55mm·year−1, under representative concentration pathways (RCP) 4.5 and RCP 8.5, respectively. Snowfall days are expected to decrease from −0.068 days·year−1 under RCP 4.5 to −0.111 days·year−1 under RCP 8.5, accompanied by an increase in the torrentiality of snowfall. As an example of the socioeconomic impacts of the changes in snow, Spandre et al. (2019) showed that under RCP8.5 projections, there would no longer be snow ski resort in the French Alps and the Pyrenees (France and Spain) by the end of the century.

5.4 The future environmental setting Serra da Estrela

The impacts of the modeled 21st century warming may be analyzed by plotting future air temperatures as its corresponding changes in elevation. Since precipitation is also forecasted to diminish significantly, a future pseudo-lowering of the Estrela accompanied by a precipitation reduction, will result in climate conditions closer to current ones in lower mountains in the region, as precipitation is much controlled by elevation in Central Portugal (Daveau, 1977; Mora & Vieira, 2020). For this, we used the altitudinal lapse rate for the Serra da Estrela by Mora (2006).

Figure 13 shows simulated comparative altitudinal modifications of the Torre Plateau, considering the SSPs and changes in mean annual temperatures compared to present-day. The results show that at 2080-2100 under ssp585, the Alto da Torre will have MAAT close to those of c. 900m asl today (Caldas de Manteigas). SSP370 will lead to warming comparable to an elevation of c. 1150m today (Poço do Inferno). SSP245 will lead to a Vale do Rossim-like climate (1400m), and the best scenario, SSP125 to a lowering of about 200 m bringing the summit to the current Lagoa Comprida conditions (1650m).

In 2040, the Torre Plateau should have MAAT between those today at c. 1600m (ssp585) and c. 1750m (ssp126). It reaches present-day’s Vale do Rossim’s (c. 1450m) conditions around 2055 under ssp585, 10 years later for ssp370 and by 2080 for ssp245. Only under ssp126 those conditions will not be met.

5.5 Impacts of a warmer and snow-depleted Estrela

The Serra da Estrela will suffer drastic warming and snow cover reduction during the 21st century, with very fast modifications already under way. These changes will have profound impacts on its sensitive ecosystems and land management systems. The plateaus will be drier and much warmer with conditions similar to those of much lower mountains today, such as Serra da Gardunha or even lower.

This lowering of the Estrela will affect the sub-alpine ecosystems of the plateaus, including key conservation habitats in the biogenetic reserve and Ramsar site, such as the peatlands, with high impacts for endemic species. The last 140 years have seen strong changes in the Estrela, with a warming of +0.17ºC/decade and a strong decrease of snow cover. The Torre Plateau is accompanying these changes by moving from a clearly seasonal snow-covered environment to one with sporadic snow and with some years showing almost no snow at all. With the reduction of shepherding in the plateau and with the warming, an expansion of the shrub formations is expected to occur. But the drying and warming will also lead to more extreme soil drought during the summer, increasingly exposing soils to water erosion and degradation during Fall and reducing even more its ecological potential.

The impacts of the vanishing snow on the hydrology can also impact water availability. An increase of water retention in the plateaus, which can be properly done having healthier and deeper soils and a denser protecting vegetation cover, is urgently needed. Conditions must be found to adapt to climate change and properly manage the vegetation in the plateaus, protecting key locations and controlling grazing, while protecting the area from wildfire.

Despite the scarce research on changes in snow cover, the reduction of snow is clear. Several tourism and regional development studies during the last decade have emphasised on the needs for adaptation of the regional tourism economy in order to diversify and become more resilient to climate change (Mota et al., 2023). Public policies and private investments have also been following this line, with tourist numbers increasing in all season. Despite more research needed, it is likely that the changes in snow cover will not have a strong impact on the local tourism industry, which is adapting to the new climate scenarios. However, it is important to note that the forecasted disappearance of seasonal snow and climate warming clearly shows that the Torre ski infrastructure has no future and that the investments made in recent years were poorly advised. The ski resort expansion in the last two decades has furthermore resulted in high impacts on the landscape, with urgent action needed for renaturalizing the slopes and for the timely removal of the infrastructure. Similar approaches are being conducted in other mountains, such as the Alps in Austria, France and Italy (Moreno-Gené et al., 2018; Polderman et al., 2020).

Conclusions

The analysis of the snow cover trends in the Serra da Estrela, specifically at the Penhas Douradas station, reveals a significant decline in snow cover days from the mid-20th century to the present, with a reduction rate of approximately 5.4 days per decade. This decline, from an average of 53 snow cover days in the 1950s dropping to just 28 days in the 2010s, mirrors similar trends observed in other European and global mountain regions, largely attributed to ongoing atmospheric warming since the industrial revolution.

Despite warming, the rate of decline in snow cover at Penhas Douradas has slowed since the 1980s. This deceleration is likely due to the station's elevation, which is sufficient to record snowfall during cold episodes but not high enough to sustain prolonged snow cover. The 1980s mark a shift to these new conditions, where snow lasting for several weeks has become rare.

Further complicating the assessment of snow cover trends in Serra da Estrela is the lack of observational data from the higher plateaus, which are crucial for understanding the full impact of changing snow cover on the ecosystem and natural resources. Attempts to reconstruct snow cover duration using data from Penhas Douradas, remote sensing, and reanalysis models faced significant challenges due to the observatory's low elevation, limitations in data resolution and optical imagery completeness. Hence, our observations need to be used with care, especially the spatial reconstruction attempt using MODIS for the period of 2001 to 2020. The reconstructed time-series indicate a substantial decline in snow cover days in the Torre plateau, from about 170 days in the late 19th century to approximately 120 days in the last decade, with increased interannual variability and more years experiencing scarce snowfall.

Projections for the 21st century under various climate scenarios predict drastic reductions in snow cover for the Torre Plateau, with some scenarios suggesting conditions by the end of the century will resemble those currently observed at much lower elevations. This anticipated decline will have profound impacts on the high-elevation ecosystems, hydrology, and land management systems of the Serra da Estrela. The sensitive sub-alpine ecosystems, including peatlands and endemic species habitats, will face increased threats from warming and drying conditions, leading to soil degradation and reduced ecological potential.

In response to these changes, adaptive management strategies are urgently needed to protect and enhance the resilience of the plateau's ecosystems. This includes improving water retention through soil and vegetation management, controlling grazing, and mitigating wildfire risks. The foreseen disappearance of seasonal snow covering the ground also calls for a reevaluation of local infrastructure investments, particularly the Torre ski resort, which is unlikely to remain viable. Instead, efforts should focus on renaturalizing impacted areas, following examples from other mountain regions like the Alps.

Overall, the findings underscore the critical need for comprehensive and forward-looking strategies to manage the impacts of climate change on snow cover and associated environmental and socioeconomic systems in the Serra da Estrela.

Authors contributions

Carla Mora: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - original draft preparation; Writing - review & editing; Visualization. Gonçalo Vieira: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Resources; Data curation; Writing - original draft preparation; Writing - review & editing; Visualization.

Acknowledgements

This research is a contribution to the Project ReMonStar (Ref PD23-00005) funded by Fundação La Caixa and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through the PROMOVE program. Thanks are due to the two anonymous referees for the comments which contributed to an improvement of the manuscript. The Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera is thanked for providing data from the Penhas Douradas meteorological station.