Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Portuguesa de Clínica Geral

versão impressa ISSN 0870-7103

Rev Port Clin Geral vol.27 no.6 Lisboa nov. 2011

ESTUDOS ORIGINAIS

Empathy in Family Medicine

Empatia em Medicina Geral e Familiar

António Macedo,* Luís Filipe Cavadas,** Marlene Sousa,*** Paulo Pires,**** José Agostinho Santos,**** Alexandra Machado****

*Médico Assistente de Medicina Geral e Familiar. USF Progresso, Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos

**Médico Assistente de Medicina Geral e Familiar. USF Lagoa, Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos

***Médica Assistente de Medicina Geral e Familiar, USF Caravela, Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos

****Médico Interno de Medicina Geral e Familiar. USF Lagoa, Unidade Local de Saúde de Matosinhos

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

AIM: Empathy is crucial in therapeutic relationships. An empathic relationship has several positive outcomes: improvement of doctor-patient relationship, increased satisfaction and diagnostic ability, and patients empowerment. This study aims to assess empathy levels in a Portuguese Primary Health Care Practice (PPHCP) and to verify the relation between doctor-patient empathy and socio-demographic characteristics.

DESIGN: cross-sectional study

LOCATION: a Portuguese Primary Health Care Practice located in Senhora da Hora, Matosinhos.

PARTICIPANTS: patients registered in the PPHCC who went to an appointment with their Family Physician (FP) during the month of June 2009.

METHODS: Empathy value measured through the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) questionnaire. Associations between variables were tested with nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis) and Pearson correlation. The adopted significance level was 0.05.

RESULTS: A sample of 353 questionnaires was obtained. FP mean empathy value was 41.1 points on a scale of 10-50 (CI 95%, 40.1-42.2). The only significant statistical association was related to educational level (p = 0.02). Patients with lower levels of formal education provided lower scores for FP empathy.

CONCLUSION: The patients of this PPHCP scored high for empathy. Lower levels of formal education were correlated with lower scores for empathy, an association not found in other studies.

Key words: Empathy, Family Practice, Physician-Patient Relationships.

RESUMO

OBJECTIVO: A empatia é essencial nas relações terapêuticas. Uma relação empática tem vários resultados positivos: melhoria da relação médico-doente,aumento da satisfação e da capacidade de diagnóstico, e um melhor empowerment do doente. Este estudo pretende avaliar a empatia dos Médicos de Família (MF) num Centro de Saúde(CS) português e verificar a relação entre o grau de empatia de médico para doente e as características sócio-demográficas do utente.

DESENHO: estudo transversal

LOCALIZAÇÃO: CS da Senhora da Hora, Matosinhos

PARTICIPANTES: utentes do CS Senhora da Hora, que efectuaram um contacto presencial com o seu MF durante o mês de Junho de 2009

MÉTODOS: O valor de empatia foi medido através do questionário Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE). As associações entre variáveis foram testadas com testes não paramétricos (Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis) e correlação de Pearson. O nível de significância adoptado foi de 0,05.

RESULTADOS: Foi obtida uma amostra de 353 questionários. O valor médio de empatia global entre os MF incluídos foi de 41,1 pontos, numa escala de 1-50 (IC 95%, 40,1-42,2). A única associação estatisticamente significativa foi com a escolaridade (p=0,02). Pacientes com baixo nível de escolaridade atribuíram pontuações mais baixas de empatia no seu MF.

CONCLUSÃO: Os utentes deste CS pontuaram um elevado grau de empatia aos seus MF. Pacientes com baixo nível de escolaridade atribuíram menor pontuação, uma associação que não foi encontrada noutros estudos.

Palavras-chave: Empatia, Medicina Familiar, Relação Médico-Doente.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most important skills of Family Physicians (FP) is the ability to effectively use the knowledge of interpersonal relationships while addressing their patients.1 These skills are not only related to the routine clinical interview (which most physicians learn during their training and is focused on obtaining a complete medical, social and family history), but also include the physicians inherent ability and motivation to grasp the emotional experience of others and, above all, to understand his patients feelings in order to use this knowledge in their treatment.2 The concept of patient-centered medicine has its roots in the paradigm of holism, which suggests that each person has a need to be understood as a biopsychosocial whole. Recent reviews on how patient-centered medicine has been defined in the literature have identified five dimensions: a biopsychosocial approach (the extension of medicine beyond the biological level and into the social and psychological levels), the patient as a person (to understand the experience of individual disease), power sharing and responsibility, the therapeutic alliance (developing a professional relationship based on care, sensitivity and empathy) and the doctor as a person (self-awareness of emotional cues in the relationship).3 Studies show that effective communication exerts a positive influence not only on mental health but also in symptom resolution, functional and physiological states, and pain control.4

Empathy is an important characteristic of therapeutic relationships and can be understood as the physicians social-emotional competence to understand the patients situation, expectations and feelings, to transmit such interpretation, and to act on that perception in a therapeutic way. Empathy is considered crucial for the development of a therapeutic relationship which contributes to a number of common objectives.5,6

There is evidence that a doctor who communicates in an empathic way gets several positive outcomes: patients expose their symptoms and concerns more often, improving the clinical interview and enhancing the doctor-patient relationship; patient satisfaction increases; the diagnostic ability is improved; and patients feel empowered to deal with their disease.5-8

Most measures designed to assess empathy were developed for use in psychiatry or nursing. Despite their origin in patient-centered therapy, there was some concern that, since the topics to be assessed by these measures were determined by healthcare professionals, they might fail to reflect the patients perspective.6 More recently, a measurement of empathy for use in Family Medicine was developed in Scotland and, along with theoretical considerations and definitions of the components of empathy, it involved information provided by patients after clinical encounters. This measure, called Consultation And Relational Empathy (CARE), is validated internationally and is a replicable measure, relevant and practical for use in the context of Family Medicine.6,9,10,11

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the FP empathy in the Senhora da Hora Health Care Center and verify the relation between the doctor-patient empathy and patients socio-demographic characteristics.

METHODS

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted during June 2009 at a Portuguese Primary Health Care Practice – PPHCP where 23 family doctors provide health services to a population of approximately 50 000 people.

The population studied consisted of patients registered in the SHHCC, excluding illiterate patients, patients who did not understand Portuguese, patients with mental impairment, and patients without an assigned FP. A convenience sample was obtained, consisting of patients that went to the SHHCC in June 2009 for an appointment with their FP (scheduled or unscheduled). An anonymous and confidential survey which included socio-demographic data and the CARE measure was handed to patients at the end of their appointment by the clerk. Sealed boxes were available in the waiting rooms for the patients to place the completed questionnaires. At the end of each day the questionnaires were collected by the authors.

The socio-demographic data obtained included age (in years), gender, educational level (less than 4 years of formal education, 4 years of formal education, 9 years of formal education, 12 years of formal education and over 12 years of formal education), occupation (student, retired, in active employment, caring for home and family, or unemployed) and appointment type (scheduled or unscheduled).

The doctor-patient relationship was assessed using the CARE measure containing a total of 10 topics rated on a Likert scale from 0 (do not know / no answer) to 5 (excellent). Questionnaires with more than two threads containing «do not know/no answer» were considered invalid. The lowest rating for the measure of empathy is 10 points, and the maximum 50 points. Throughout this paper empathy will refer to the doctors degree of empathy as reported, or perceived, by patients.

Before the study the CARE measure was adapted to the Portuguese language via a translation by a professional translator, followed by a pilot test applied to a convenience sample of 30 patients of the Health Care Centre. At the end of this pilot study the questionnaire was revised and applied in this study. The Portuguese translation was not back-translated to English.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Local Health Unit of Matosinhos, the institution where it was performed.

Data processing

Data were processed by computer and recorded in Microsoft Excel®. Statistical treatment of results was performed with SPSS 15.0 for Windows®. Descriptive statistics of the sample were carried out with calculation of percentages for qualitative variables and measurements of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables. Associations between variables were performed by Pearson correlation and nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis). The level of statistical significance adopted was 0.05.

RESULTS

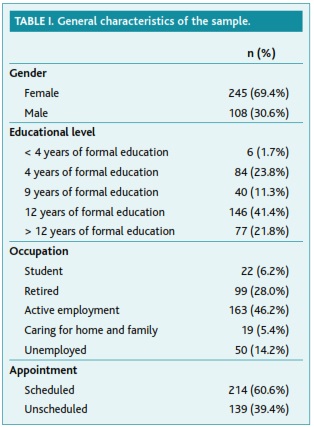

During the data collection period the authors obtained 353 valid questionnaires, of which 245 (69.4%) were from female patients and 108 (30.6%) from male patients. The mean age was 47.5 years with a minimum of 9 years and a maximum of 83 years of age. Table I describes the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. During the collection period there were 1267 people who attended the SHHCC and who could answer the questionnaire. Considering the 353 valid questionnaires obtained, the authors calculated a 27,9% participation rate.

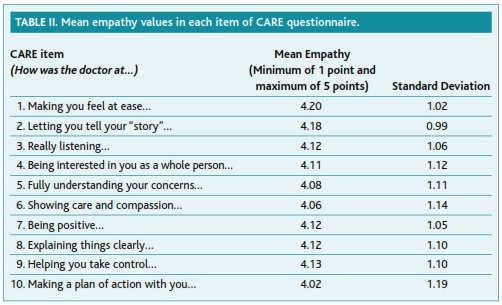

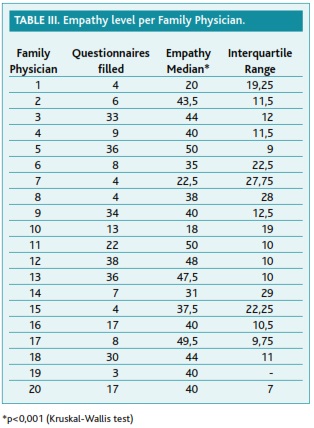

Of the 353 questionnaires, 214 (60.6%) were filled in by patients with a scheduled appointment and 139 (39.4%) by patients with an unscheduled appointment. The mean value of the empathy score obtained by the CARE measure was 41.1 points, with a standard deviation (SD) of 9.8, a minimum of 10 points and a maximum of 50 points. Table II presents the mean values for each item of the CARE measure. The valid questionnaires obtained corresponded to 20 FP from the studied Health Care Centre. Table III shows the range of questionnaires per FP and respective empathy level.

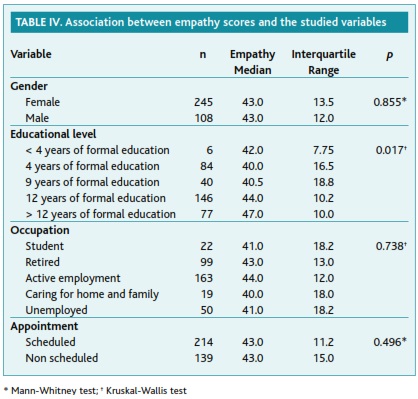

As the empathy score does not have a normal distribution, the nonparametric tests of Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis were used to investigate the association between empathy and the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample (Table IV). Pearsons correlation was applied to test the association between empathy and age.

The Pearson correlation of these two variables was equal to 0.004 with a p value of 0.947, which leads to the conclusion that age had no association with empathy score in this study. Also, as described in Table IV, there were no statistically significant relations between the empathy score and gender (p = 0.855), occupation (p = 0.738) and type of appointment (p = 0.496). However, the authors found a statistically significant relation between the empathy score and educational level (p = 0.017). Educational levels higher than 4 years of formal education gave progressively greater scores for empathy. From the analysis of these results the authors have also noticed that the group with less than 4 years of formal education had higher empathy scores than the group with 4 years of formal education. However, since this group has only 6 observations, we considered it as a non-representative group with no interference in the overall analysis of data.

DISCUSSION

These results show that the FP level of empathy in this Primary Health Care Centre was high. In all items of the empathy score the ratings ranged from very good to excellent.

This study attempted a structured and objective assessment of empathy, a very important but highly subjective component of the Family Medicine consultation. The authors chose a validated and reliable measurement of empathy10,11 in the form of an anonymous and confidential questionnaire to avoid informant bias. In this case, where a questionnaire to be filled in by the patient was applied, there may be situations where the doctor-patient empathetic relationship is not achieved and the patient may choose not to answer the questions, which can lead to biased results. The option for an anonymous and confidential questionnaire tried to prevent this. The evaluated physicians, al-though previously informed about the study, were not informed about the time of data collection to avoid any conditioning of their consultation. A professional translator translated the CARE questionnaire into Portuguese and a pilot study was carried out to minimize patients difficulties in the interpretation.

Limiting the conclusions of this study are the facts that it was conducted in only one Primary Health Care Center, there was no sample randomization and the study period was short (one month). These limitations compromise the generalisation of the results. There was also a low response rate which raises the chance of a bias in that more satisfied patients were more likely to respond, leading to a falsely high rating of FP empathy.

The mean empathy score obtained in this study was high (mean 41.1; SD 9.8) and similar to that in other studies that used the same measure, including Mercer SW et al and Fung CSC et al performed in populations in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong.10,12-15

This study found a relationship between the empathy score and educational levels: patients with lower educational levels scored lower for empathy. This association was not found in other studies. In the Mercer SW et al study, conducted during the development of the CARE measure, age had a significant effect on the empathy score (younger patients scored lower for empa-thy), a feature not observed in this study. In contrast, in that study there were no significant differences regarding the educational level or other socio-demographic characteristics studied.10

In the United Kingdom the CARE questionnaire is widely used in FP evaluation and training, in which capacity it has proved to be highly reliable.10 However, structured studies of the characteristics of doctor-patient relationship in primary care in Portugal and in other countries are lacking. One of the aims of this study is to raise awareness of the importance of assessing inter-personal relationships in medicine, in addition to other biomedical components. This paper aims to inform FPs about the existence of objective and valid measurements for this evaluation and the benefits of their use in daily practice and training. As such Table III shows a statistical difference in empathy levels between the 20 family doctors of the study and identifies some doctors with low levels of empathy. This knowledge is important to quantify problems in doctor-patient relation and communication and is the starting point for its improvement.

The validation of the CARE measure for the Portuguese language is of considerable importance to conduct future studies in Portugal. It will be important to clarify the association of empathy with the educational level and with the other socio-demographic factors described in this work. The study of the association between empathy and variables described in international articles, including the severity and chronicity of diseases common in primary care and the different ways of conducting the consultation, may also be important.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank their Family Medicine trainers for their cooperation in this work and the Investigation group of Coordenação do Internato de Medicina Geral e Familiar da Zona Norte for their assistance on the statistical analysis and revision of the manuscript.

The authors also wish to thank Joana Styliano for her exceptional aid in the translation process.

REFERENCES

1. Rakel RE. The Family Physician. In: Rakel RE. Textbook of Family Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. p. 3-14. [ Links ]

2. Quirk M, Mazor K, Haley HL, Philbin M, Fischer M, Sullivan K, et al. How patients perceive a doctors caring attitude. Patient Educ Couns 2008 Sep; 72 (3): 359-66. [ Links ]

3. Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; (4): CD003267. [ Links ]

4. Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ 1995 May 1; 152 (9): 1423-33. [ Links ]

5. Reynolds WJ, Scott B. Empathy: a crucial component of the helping relationship. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 1999 Oct; 6 (5): 363-70. [ Links ]

6. Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract 2002 Oct; 52 Suppl: S9-12. [ Links ]

7. Neumann M, Wirtz M, Bollschweiler E, Mercer SW, Warm M, Wolf J, et al. Determinants and patient-reported long-term outcomes of physician empathy in oncology: a structural equation modelling approach. Patient Educ Couns 2007 Dec; 69 (1-3): 63-75. [ Links ]

8. Mercer SW, Reilly D, Watt GC. The importance of empathy in the enablement of patients attending the Glasgow Homoeopathic Hospital. Br J Gen Pract 2002 Nov; 52 (484): 901-5. [ Links ]

9. Mercer SW, Maxwell M, Heaney D, Watt GC. The consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure: development and preliminary validation and reliability of an empathy-based consultation process measure. Fam Pract 2004 Dec; 21 (6): 699-705. [ Links ]

10. Mercer SW, McConnachie A, Maxwell M, Heaney D, Watt GC. Relevance and practical use of the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure in general practice. Fam Pract 2005 Jun; 22 (3): 328-34. [ Links ]

11. Mercer SW, Murphy DJ. Validity and reliability of the CARE Measure in secondary care. Clin Gov Int J 2008; 13 (4): 269-83. [ Links ]

12. Mercer SW, Neumann M, Wirtz M, Fitzpatrick B, Vojt G. General practitioner empathy, patient enablement, and patient-reported outcomes in primary care in an area of high socio-economic deprivation in Scotland: a pilot prospective study using structural equation modeling. Patient Educ Couns 2008 Nov; 73 (2): 240-5. [ Links ]

13. Mercer SW, Fitzpatrick B, Gourlay G, Vojt G, McConnachie A, Watt GC. More time for complex consultations in a high-deprivation practice is associated with increased patient enablement. Br J Gen Pract 2007 Dec; 57 (545): 960-6. [ Links ]

14. Mercer SW, Watt GC. The inverse care law: clinical primary care encounters in deprived and affluent areas of Scotland. Ann Fam Med 2007 Nov-Dec; 5 (6): 503-10. [ Links ]

15. Fung CS, Hua A, Tam L, Mercer SW. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the CARE Measure in a primary care setting in Hong Kong. Fam Pract 2009 Oct; 26 (5): 398-406. [ Links ]

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

Luís Filipe Cavadas and Marlene Sousa are members of the editorial board of Revista Portuguesa de Clínica Geral but took no part in the editorial process for this article. Paulo Pires and José Agostinho Santos are editors of the Journal Club of Revista Portuguesa de Clínica Geral and similarly were not involved in the editorial process for this article.

António Macedo

Rua D. João de Castro, 225

4435-674 Baguim do Monte

Porto - Portugal

Recebido em 03/07/2011

Aceite para publicação em 07/10/2011