Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Psicológica

versão impressa ISSN 0870-8231versão On-line ISSN 1646-6020

Aná. Psicológica vol.34 no.4 Lisboa dez. 2016

https://doi.org/1014417/ap.1122

Coping as a moderator of the influence of economic stressors on psychological health

Saúl Neves Jesus1, Ana Rita Leal2, João Nuno Viseu2, Patrícia Valle3, Rafaela Dias Matavelli2, Joana Pereira4, Esther Greenglass5

1Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade do Algarve / Centro de Investigação sobre o Espaço e as Organizações, Universidade do Algarve

2Centro de Investigação sobre o Espaço e as Organizações, Universidade do Algarve

3Faculdade de Economia, Universidade do Algarve / Centro de Investigação sobre o Espaço e as Organizações, Universidade do Algarve

4Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais, Universidade do Algarve

5Department of Psychology, York University, Canada

ABSTRACT

Since 2008, there has been a decline in the economy of several European countries, including Portugal. In the literature, it is emphasized that periods of economic uncertainty propitiate the appearance of mental health problems and diminish populations’ well-being. The aim of the present study, with 729 Portuguese participants, 33.9% (n=247) males and 66.1% (n=482) females with an average age of 37 years old (M=36.99; SD=12.81), was to examine the relationship between economic hardship, financial threat, and financial well-being (i.e., economic stressors) and stress, anxiety, and depression (i.e., psychological health indicators), as well as to test the moderation effect of coping in the aforementioned relationship. To achieve these goals, a cross-sectional design was implemented and structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the obtained data. Our results underline that coping affects the relationship between economic stressors and psychological health since subjects with lower coping levels are more vulnerable to economic stress factors than those with higher coping levels. The moderation effect was more evident in the relationships between economic hardship and stress, anxiety, and depression. The main implications of this study are presented, as well as its’ limitations and suggestions for future research.

Key words: Anxiety, Coping, Depression, Economic stressors, Stress.

RESUMO

Desde 2008, tem havido um declínio na economia de vários países europeus, incluindo Portugal. Na literatura, enfatiza-se que períodos de incerteza económica propiciam o aparecimento de problemas de saúde mental e diminuem o bem-estar das populações. No presente estudo foram usados 729 participantes portugueses, 33,9% (n=247) homens e 66,1% (n=482) mulheres, com uma idade média de 37 anos (M=36,99, DP=12,81). Este estudo teve por objetivo analisar a relação entre as dificuldades económicas, a ameaça financeira e o bem-estar financeiro (stressores económicos) e os níveis de stresse, ansiedade e depressão (ou seja, indicadores de saúde psicológica), bem como para testar o efeito de moderação do coping nesta relação. Este modelo foi analisado através de equações estruturais (SEM). Os resultados obtidos revelam que o coping afeta a relação entre os stressores económicos e a saúde psicológica, uma vez que os sujeitos com menores níveis de coping são mais vulneráveis a fatores de stresse económico do que aqueles com níveis de coping mais elevados. O efeito de moderação foi mais evidente nas relações entre as dificuldades económicas e o stresse, a ansiedade e a depressão. São apresentadas as principais implicações deste estudo, bem como as suas limitações e sugestões para futuras pesquisas.

Palavras-chave: Ansiedade, Coping, Depressão, Stressores económicos, Stresse.

Since 2008, several countries are facing the worse financial and economic crisis since the 1930s, particularly in Europe (e.g., Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain) (Yurtsever, 2011). Two major aspects have been pointed as the source of this period, problems in the banking system, which led to the bankruptcy of numerous banks, and high levels of sovereign debt (Torres, 2009; Yurtsever, 2011). The main consequences of adverse economic periods are the increase in: (a) job insecurity; (b) unemployment, predominantly youth unemployment; (c) families debt levels; and (d) household costs (Boone, van Ours, Wuellrich, & Zweimuller, 2011; Keegan, Thomas, Normand, & Portela, 2013). Other aspects are worth considering, namely: (a) decreases in wages; (b) loss of purchasing power; (c) reductions in social service benefits; (d) decline in healthcare expenditures; and (e) reduced response capacity from social support nets (Boyd, Tuckey, & Winefield, 2013; Keegan et al., 2013; Marjanovic, Greenglass, Fiksenbaum, & Bell, 2013).

Due the above mentioned aspects, it is possible to state that economic recessions generate uncertainty and threat perceptions in populations, which may potentiate the appearance of mental health problems (Cooper, 2012). There is a substantial body of knowledge (e.g., Catalano et al., 2011; Sociedad Española de Salud Pública y Administración Sanitária, 2011) that points to the influence of economic crises on populations’ physical and mental health, especially through the social and behavioral effects that these periods induce. Several researches (e.g., Althouse, Allem, Childers, Dredze, & Ayers, 2014; Catalano et al., 2011; Frank, Davis, & Elgar, 2013; Norvilitis, Szablicki, & Wilson, 2003) demonstrated the relationship between financial problems and negative health-related consequences, such as (a) psychological distress; (b) depression; (c) anxiety; (d) low life satisfaction; (e) dysfunctional impulsivity; (f) suicide; (g) hypertension; (h) myocardial infarction; (i) diabetes; and (j) infections. Thus, we present below a set of studies that underlined the existence of a relationship between anxiety, depression, and distress (i.e., psychological health indicators), and economic stressors (i.e., economic hardship, financial threat, and financial well-being).

Economic hardship is associated with a variety of physical and psychological health problems (e.g., distress and depression) (Greenglass, Marjanovic, & Fiksenbaum, 2013; Sargent-Cox, Butterworth, & Anstey, 2011). The combination of situations of economic hardship, financial threat, and lack of financial well-being also contributed to the appearance of negative psychological outcomes (Kim, Garman, & Sorhaindo, 2003; Marjanovic et al., 2013; Norvilitis et al., 2003). Well-being can be affected by work-related aspects (Fenge et al., 2012), such as job dissatisfaction and unemployment, two common situations in contexts of economic turmoil, which potentiate depressive symptoms. In turn, Prawitz et al. (2006) observed that a perception of low financial well-being is responsible for an increase in distress levels.

The above mentioned studies emphasize the importance of analyzing the psychological impact of the current economic and financial crisis, especially in countries like Portugal which requested extraordinary funding from the International Monetary Fund, European Central Bank, and European Commission (Yurtsever, 2011). Despite this situation, Portugal was already implementing austerity measures before the request for financial support, nevertheless they were considered insufficient (Torres, 2009). The Portuguese labor market suffered greatly with the austerity measures implemented, in the second semester of 2014 the unemployment rate was 13.9% and in the second quarter of the same year the youth unemployment rate was 35.6% (Statistics Portugal, 2014). According to the Portuguese Observatory of Health Systems (2014), the main consequences of austerity were: (a) anxiety; (b) depression; (c) low self-esteem; (d) helplessness; and (e) suicide attempts, aspects that are mainly associated with (a) unemployment; (b) unemployment threat; (c) indebtedness; and (d) sudden impoverishment (Falagas, Vouloumou, Mavros, & Karageorgopoulos, 2009). Thus, we can conclude that the current economic crisis and its’ relationship with unemployment may conduce to acute states of distress and mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety (Almeida & Xavier, 2013).

In order to deal with these negative outcomes, individuals must adapt coping behaviors. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) emphasized that coping behaviors are used when a stressful event emerges, aiming to decrease the stressors’ intensity and preventing the appearance of psychopathology. Numerous studies (e.g., Chen et al., 2012; Stein et al., 2013) highlighted that coping strategies moderate the effects of economic stress on psychological health indicators. Therefore, coping behaviors are employed when stressful events (e.g., economic and financial crises) arise and moderate their relationship with an individual’s psychological health, reducing the negative impact of, for example, stress, anxiety, and depression. The traditional approach to coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) views this concept as having a reactive nature, i.e., a subject employs coping strategies in the presence of an adverse situation. However, Greenglass (2002) propose a different type of coping, proactive coping, where coping strategies are implemented before the appearance of a stressful event (i.e., coping possesses a proactive nature). This type of coping is future-oriented and closely related with the capacity to mobilize individual resources when a subject anticipates potential threatening situations (Greenglass, 2002; Greenglass & Fiksenbaum, 2009). In the opinion of Greenglass and Fiksenbaum (2009), proactive coping contributes to psychological health and well-being. This was the coping approach adopted in the present study.

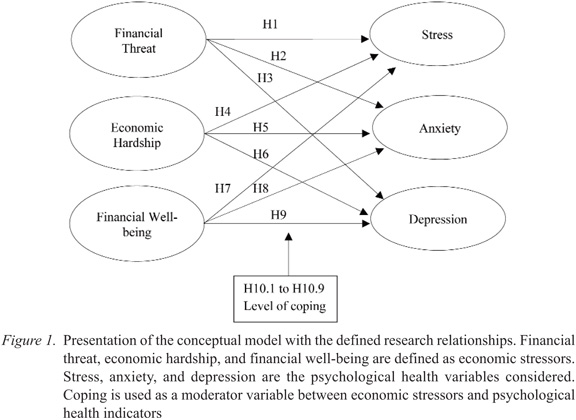

Based on the previous assumptions, the objective of this study was to analyze the impact of economic stressors, such as economic hardship, financial threat, and financial well-being, on stress, anxiety, and depression, defined as psychological health indicators, as well as to test the moderating effect of coping in the aforementioned relationship. Figure 1 presents the theoretical model with the respective research hypotheses.

Overall, our model relies on the assumption that economic stress variables significantly influence the psychological health variables. So, we are expecting that the relationships H1 to H9 are positive and statistically significant. Also, this study aimed to assess to what extent positive coping strategies can affect the strength of these relationships. More specifically, we propose that the later are significantly lower within individuals with good coping strategies. In accordance, hypotheses H1 to H9 state that coping moderates the causal relationships between economic stressors and psychological health variables. For example, Figure 1 shows that the relationship between financial threat and stress is moderated by the individuals’ coping levels. Overall, our hypotheses propose that individuals with worse coping strategies will show a significantly stronger association between economic stressors and psychological health variables than those with better coping strategies.

Method

Participants

The sample was composed by 729 Portuguese participants (66.1% females: 482; 33.9% males: 247) with a mean age of 37 years old (M=36.99; SD=12.81). Relatively to the marital status, 51.9% were married or living in common law, 40.6% were single, 6.5% were separated or divorced, and 1% were widowed. In the case of employment status, 79.3% were employed, 4.7% were retired, and 16% were unemployed.

Regarding the average monthly income of the respondents, a value of 1254 euros (M=1254.36; SD=1758.45) was registered. In the case of monthly expenses, on average, the participants spent 813 euros (M=813.52; SD=683.12). Also, 72.9% of the participants reported that their financial condition worsened or greatly worsened between 2011 and 2013. Moreover, 56.4% of the respondents have the perception that, in the future, their financial situation will worsen or greatly worsen.

Measures

Economic hardship was assessed by the Economic Hardship Questionnaire (EHQ) (Lempers, Clark-Lempers, & Simon, 1989) that included 10 items (e.g., During the last few years, did your family cut back on social activities and entertainment expenses?) organized in a four-point scale (1 – Never; 4 – Very often). The EHQ evaluates the cutbacks that individuals and families have to make in contexts of economic adversity. The Cronbach’s Alpha value of this questionnaire in the present study was .85 (M=2.49; SD=.65). Financial threat was evaluated with the Financial Threat Scale (FTS) (Marjanovic et al., 2013). This scale presented five items (e.g., What is the likelihood you will have to declare bankruptcy to manage your debt?) with a five-point scale (1 – Not at all; 5 – Extremely uncertain) and analyzes the threat perceptions individuals feel regarding their financial situation. A Cronbach’s Alpha value of .91 (M=3.30; SD=.86) was registered in the current study. Financial well-being was measured by the Financial Well-Being Scale (FWBS) (Norvilitis et al., 2003) that contained eight items (e.g., I am uncomfortable with the amount of debt I am in.) with five answer options (1 – Strongly disagree; 5 – Strongly agree). The FWBS (Norvilitis et al., 2003) estimates one’s well-being concerning its’ financial status. This scale presented a Cronbach’s Alpha value of .79 (M=24.77; SD=5.92).

Stress, anxiety, and depression were assessed with the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21-item version (DASS-21) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). This scale possessed 21 items (e.g., I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything.) that were divided in three dimensions, with seven items each, which measured stress, anxiety, and depression. DASS-21 also presented a four-point response scale (0 – Did not apply to me at all; 3 – Applied to me very much, or most of the time – Almost always). This scales’ three dimensions achieved values of Cronbach’s Alpha in this study of: (a) .92 (M=7.17; SD=5.39): stress; (b) .90 (M=4.06; SD=4.51): anxiety; and (c) .86 (M=4.85; SD=4.84): depression.

Lastly, coping was evaluated by the Pro-Active Coping Scale (PACS) (Greenglass, Schwarzer, & Taubert, 1999), one of the scales of the Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI), which presented 14 items (e.g., After attaining a goal, I look for another, more challenging one) organized in a four-point scale (1 – Not at all true; 4 – Completely true). PACS refers to the coping strategies adopted by an individual in the presence of potential stressful events and underlines the importance of adopting an active attitude towards those events. The Cronbach’s Alpha obtained in PACS was .75 (M=2; SD=.45).

Procedures

A research protocol, that analyzed economic stressors and psychological health indicators, was administered between the months of March and June 2013 in Portugal. The application process occurred online, via email, where the participants were informed about the research objectives. Only the questionnaires from participants over 18 years old were considered. The collected sample was part of a contact database designed through previous research projects of a Portuguese research center. In order to reach the highest number of participants as possible, the contacted respondents were asked to forward the received email to their contacts.

Data analysis

As a first step in the analysis, the scale of some items was reverted with the purpose of ensuring that, regarding each construct, high values in all items indicated a positive perception on that construct. According to this procedure, higher values on the scales imply higher levels of economic stress (i.e., high perceptions of financial threat and economic difficulties, and low perception of financial well-being), psychological malaise (i.e., high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression), and positive coping strategies. Then, the seven constructs (i.e., financial threat, economic hardship, financial well-being, stress, anxiety, depression, and coping) and the corresponding items were subject to an exploratory reliability analysis. In this analysis, only items with a Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CI-TC) coefficient higher than .3 were considered to show enough correlation with the corresponding construct and, thus, remained in the study (Betz, 2000). Items measuring stress, anxiety, and depression, which were not eliminated after the reliability analysis, were considered as indicators of these constructs in the structural equation model (SEM) proposed in Figure 1. Regarding coping, the items that remained after the reliability analysis were used to build a coping score for each subject by summing the corresponding items. Then, for each subject the average coping score was computed. In this new variable high values mean good coping strategies and vice-versa. Based on the mean of this variable the subjects were classified in two groups: (a) those with low coping strategies (i.e., with a mean score less than or equal to 2 [n=409]); and (b) those with high coping strategies (i.e., with a mean score higher than 2 [n=322]).

The analysis proceeded by applying SEM to test the relationship between the economic stress variables, once moderated by the coping variable, and the psychological health variables. The software AMOS 20 was applied to conduct the analysis and the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method was used to estimate the model. The invariance of the measurement and structural models across the two groups was assessed in advance by comparing the unconstrained model (allowing all parameters, loadings and path coefficients, to be different in the two groups) with a constrained model where all the parameters were fixed to be equal across the two groups. The Chi-square statistic was used to test the significance of the difference between the models. The analysis of the overall model fit relied on three types of measures: (a) absolute fit; (b) incremental fit; and (c) parsimonious fit (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). The measurement model was assessed in terms of reliability and validity. The moderating effect of coping was tested using a multiple group analysis procedure. In particular, the Z statistics provided by AMOS allowed us to test the significance of the differences between the pairs of path coefficients for the two groups. A significance level of .05 was used to perform the analysis.

Results

Testing the invariance of the model parameters

Before comparing the path coefficients between the two groups, measurement invariance was tested to identify if the measurement models were invariant across groups. With this purpose, a constrained model where all the loadings were fixed to be equal across groups reported a significantly better fit than an unconstrained model where all the loadings were allowed to be different in the two groups (χ2=41.252; p=.065). These results indicate that the measurement model can be assumed to be invariant across the two groups: (a) those with better coping strategies; and (b) those with worse coping strategies. However, a structural model where all the path coefficients were constrained to be equal for the two groups presents a significantly worse fit than an unconstrained model where the path coefficients can be different in the two groups (χ2=23.340; p=.005). This significant difference suggests that the relationship pattern differs across groups.

Overall model fit

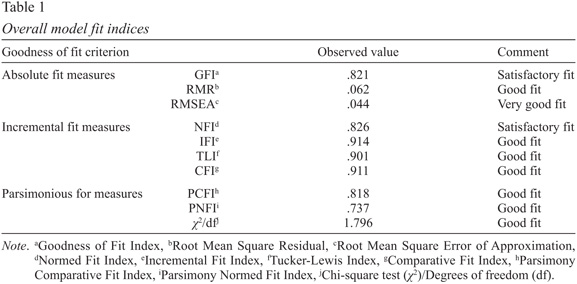

The model assuming the same loadings across groups (measurement invariance) and free path coefficients across groups (structural variance) was estimated using AMOS multiple-group analysis. Then, the model was assessed regarding the overall model fit which implies a threefold evaluation: (a) absolute fit; (b) incremental fit; and (c) parsimonious fit. In terms of absolute fit, results show a high and statistically significant Chi-square statistics (χ2=1919.853; p<.01), suggesting a significant difference between the actual and predicted models. However, given that this test is too sensitive to large sample sizes, other absolute fit indexes should be observed (Anderson & Gerbing, 1982). In this regard, a good absolute fit was observed Table 1 giving the GFI (.821), RMR (.062), and the RMSEA values (.044). In terms of incremental and parsimonious adjustment, results indicate a moderate to good model (NFI=.826; IFI=.914; TLI=.901; CFI=.911; PCFI=.818; PNFI=.737; χ2/df=1.796). These results are also indicative of configurational invariance which means that the set of items to measure the latent constructs is the same across the groups.

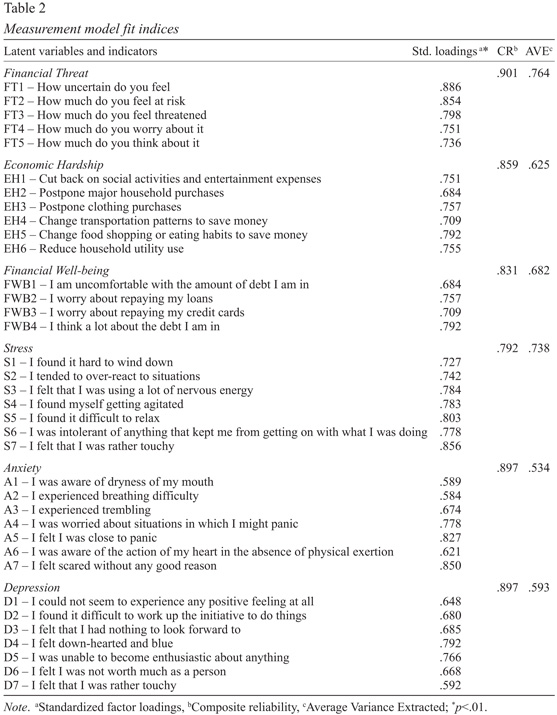

Measurement model fit

A suitable measurement model fit is required before the relationships between the latent variables can be assessed (Anderson & Gerbing, 1982). The main results from the measurement model analysis are presented in Table 2. As can be observed, all indicators report individual reliability, since all standardized factor loadings surpass the threshold value of .5 and are statistically significant (p<.01). Construct reliability is also found as evidenced by a high Cronbach’s Alpha value and Composite Reliability (CR) coefficients (Kline, 1998). The model also reports good convergent validity given that all Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values are higher than the threshold value of .5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Concerning discriminant validity, each AVE value should be higher than the squared correlation between the corresponding construct and the other. This condition is applied to the six latent variables (i.e., financial threat, financial well-being, economic hardship, stress, anxiety, and depression).

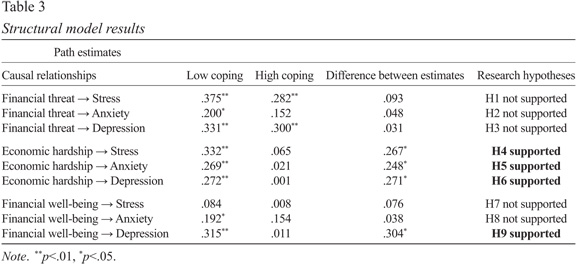

Structural model parameters

Table 3 shows the standardized path estimates of the structural model proposed in Figure 1 in the two groups. In the group with high coping scores, all nine estimates are positive meaning that strong economic stress is associated with higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. From these relations, only two are statistically significant: (a) the relationship between financial threat and stress (standardized coefficient=.282; p<.01); and (b) the relationship between financial threat and depression (standardized coefficient=.300; p<.01). The results are quite different in the group with low coping scores. In this group, the estimates are also positive which underlines the existence of a positive association between economic stressors and psychological health problems. However, the number of significant relationships is much larger in this group than in the group with high coping. Within individuals with low coping strategies, only the relationship between financial well-being and stress is not significant (standardized coefficient=0.084; p=.294).

Table 3 also presents the differences between the pairs of coefficients. The differences are significant concerning the relationships involving economic hardship and stress (H4), economic hardship and anxiety (H5), economic hardship and depression (H6), and also between financial well-being and depression (H9) (Z scores of 1.851, 1.720, 2.17, and 2.11, respectively, all p<.05). The significance of the differences was assessed by comparing the Z scores for differences between the pairs of coefficients provided by AMOS with the critical values for the Z distribution of 1.645 and 3.07, for a 5% and 1% significance level, respectively, and assuming one sided tests for the research hypotheses. In short, coping significantly moderates the relationship between specific economic stressors, especially economic hardship, and psychological health.

Discussion

Globally, our results show that coping affects the relationship between economic stress variables and psychological health variables. The effect of economic stressors on psychological health variables is always positive in the two groups and, in general, the effects are significant within individuals with low coping strategies. The obtained results allow us to draw some conclusions. It was observed that the stronger the coping strategies employed by individuals are, the less vulnerable their psychological health will be to economic stress factors. In most cases, in the high coping group, the effect of coping decreased the magnitude and statistical significance of the association between the economic stress and psychological health variables. However, in the group with low coping values it was verified that, in most situations, individuals continued to suffer a significant incidence of economic stress factors on their mental health. Except for one case (i.e., relationship between financial well-being and stress), the effect of coping was not able to mitigate the adverse effects of economic stress on mental health. When comparing the two groups (i.e., high coping scores vs. low coping scores) it was registered that coping strategies were more effective in the relationships between economic hardship and stress (H4), anxiety (H5), and depression (H6), and between financial well-being and depression (H9). In sum, our findings highlight that, despite the importance of coping strategies, their influence will be more effective when subjects present high coping levels. In the presence of subjects with low coping levels, the moderation effect of this construct will not be able to attenuate the negative impact of economic stress factors on mental health.

This is congruent with the assertions of Lazarus (1966) and Lazarus and Folkman (1984) when they affirm that the use of coping behaviors “protects” individuals’ psychological health from potential menaces. However, if we consider the coping theoretical framework used in this study, we can conclude that it may not be sufficient for individuals to adopt an active attitude in the anticipation of potential threatening situations (e.g., economic and financial crises), they should also employ their individual resources in order to guarantee that the coping strategies used are sufficiently robust to prevent that those negative situations affect their mental health.

This study possesses implications for the development of preventive measures that can be used in similar situations (e.g., future economic crises). Intervention programs involving skill training, in particular those who teach how to use coping strategies, could avert mental health deterioration in times of economic recession. Stress management interventions (e.g., Bjorn, Jesus, & Casado-Morales, 2013; Jesus, Miguel-Tobal, Rus, Viseu, & Gamboa, 2014; Neto & Marujo, 2007; Santos, Pais-Ribeiro, & Guimarães, 2003) may also be an important way to prevent stress, anxiety, and depression, namely because they teach individuals to: (a) cope with potential stressors; (b) use adequate coping strategies; (c) implement relaxation techniques; and (d) develop healthy lifestyles. Unemployed subjects might be the primary target of these interventions, however these programs may be useful for adults in general, namely in organizations for workers and in universities for students.

The present study possesses limitations regarding the sampling process. Firstly, the collected sample should present a higher number of participants, seeking to ensure the strength of the obtained results. Secondly, other type of participants could have been studied (e.g., children and adolescents from families with economic difficulties) to analyze the importance of family coping strategies. The use of a cross-sectional design may also be considered as a limitation, because data collection at one single moment does not allow the assessment of how different variables relate with each other at different time-frames, inhibiting the realization of comparisons. Additionally, this type of design impedes the inference of causality.

Future research should examine the hypothesized model using longitudinal data, in order to address conceptual and methodological issues concerning inferences of causality. Furthermore, other moderator variables (e.g., social support) can be used, trying to understand their effect on the relationship between economic stressors and psychological health indicators. Finally, it would be useful to realize similar studies in other European countries (e.g., Greece) affected by the financial crisis, with the objective of comparing the obtained results.

References

Almeida, J. M. C., & Xavier, M. (2013). Estudo epidemiológico nacional de saúde mental: 1º relatório [National epidemiological study of mental health: 1st report]. Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. Accessed from http://www.fcm.unl.pt/main/alldoc/galeria_imagens/Relatorio_Estudo_Saude-Mental_2.pdf [ Links ]

Althouse, B., Allem, J., Childers, M., Dredze, M., & Ayers, J. (2014). Population health concerns during the United States’ great recession. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46, 166-170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.008

Anderson, J., & Gerbing, D. (1982). Some methods of respecifying measurement models to obtain unidimensional construct measurement. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 453-460. doi: 10.2307/3151719 [ Links ]

Betz, N. (2000). Test construction. In F. Leong & J. Austin (Eds.), The psychology research handbook: A guide for graduate students and research assistants (pp. 239-250). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Bjorn, M., Jesus, S. N., & Casado-Morales, M. (2013). Relaxation strategies during pregnancy: Health benefits. Clínica y Salud, 24, 77-83. doi: 10.5093/cl2013a9 [ Links ]

Boone, J., van Ours, J., Wuellrich, J., & Zweimuller, J. (2011). Recessions are bad for workplace safety. Journal of Health Economics, 30, 764-773. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1816292 [ Links ]

Boyd, C., Tuckey, M., & Winefield, A. (2013). Perceived effects of organizational downsizing and staff cuts on the stress experience: The role of resources. Stress and Health, 30, 53-64. doi: 10.1002/smi.2495 [ Links ]

Catalano, R., Goldman-Mellor, S., Saxton, K., Margerison-Zilko, C., Subbaraman, LeWinn, K., & Anderson, E. (2011). The health effects of economic decline. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 431-450. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth [ Links ]

Chen, L., Li, W., He, J., Wu, L., Yan, Z., & Tang, W. (2012). Mental health, duration of unemployment, and coping strategy: A cross-sectional study of unemployed migrant workers in eastern China during the economic crisis. BMC Public Health, 12, 597. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-597 [ Links ]

Cooper, C. (2012). Stress in turbulent economic times. Stress and Health, 28, 177-178. doi: 10.1002/smi.2442 [ Links ]

Falagas, M. E, Vouloumanou, E. K, Mavros, M. N., & Karageorgopoulos, D. E. (2009). Economic crises and mortality: A review of literature. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 63, 1128-1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02124.x [ Links ]

Fenge, L., Hean, S., Worswick, L., Wilkinson, C., Fearnley, S., & Ersser, S. (2012). The impact of the economic recession on well-being and quality of life of older people. Health and Social Care in the Community, 20, 617-624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01077.x [ Links ]

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39-50. doi: 10.2307/3151312 [ Links ]

Frank, C., Davis, C., & Elgar, F. (2013). Financial strain, social capital, and perceived health during economic recession: A longitudinal survey in rural Canada. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 27, 422-438. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.864389 [ Links ]

Greenglass, E. (2002). Proactive coping. In E. Frydenberg (Ed.), Beyond coping: Meeting goals, vision, and challenges (pp. 37-62). London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Greenglass, E., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2009). Proactive coping, positive affect, and well-being: Testing for mediation using path analysis. European Psychologist, 14, 29-39. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.29 [ Links ]

Greenglass, E., Marjanovic, Z., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2013). The impact of the recession and its aftermath on individual health and well-being. In A. Antoniou & C. Cooper (Eds.), The psychology of the recession on the workplace (pp. 42-58). Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Greenglass, E., Schwarzer, R., & Taubert, S. (1999). The Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI): A multidimensional research instrument [on-line publication]. Accessed from http://www.psych.yorku.ca/greenglass/ [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis with readings (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall International. [ Links ]

Jesus, S. N., Miguel-Tobal, J., Rus, C., Viseu, J., & Gamboa, V. (2014). Evaluating the effectiveness of a stress management training on teachers and physicians stress related outcomes. Clínica y Salud, 25, 111-115. doi: 10.1016/j.clysa.2014.06.004 [ Links ]

Keegan, C., Thomas, S., Normand, C., & Portela, C. (2013). Measuring recession severity and its impact on health expenditure. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics, 13, 139-155. doi: 10.1007/s10754-012-9121-2 [ Links ]

Kim, J., Garman, E. T., & Sorhaindo, B. (2003). Relationship among credit counseling clients’ financial well-being, financial behaviors, financial stressor events and health. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 14, 75-87.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Software review: Software programs for structural equation modeling: AMOS, EQS, and LISREL. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 16, 343-364. doi: 10.1177/073428299801600407 [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress appraisal and coping. New York, NY: Springer. [ Links ]

Lempers, J., Clark-Lempers, D., & Simons, R. (1989). Economic hardship, parenting, and distress in adolescence. Child Development, 60, 25-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb02692.x [ Links ]

Lovibond, S., & Lovibond, P. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney, Australia: Psychology Foundation. [ Links ]

Marjanovic, Z., Greenglass, E., Fiksenbaum, L., & Bell, C. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the Financial Threat Scale (FTS) in the context of the great recession. Journal of Economic Psychology, 36, 1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2013.02.005 [ Links ]

Neto, L., & Marujo, H. (2007). Propostas estratégicas da psicologia positiva para a prevenção e regulação do stress. Análise Psicológica, XXV, 585-593. [ Links ]

Norvilitis, J. M., Szablicki, P. B., & Wilson, S. D. (2003). Factors influencing levels of credit card debt in college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 935-947. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01932.x [ Links ]

Prawitz, A., Garman, E. T., Sorhaindo, B., O’Neill, B., Kim, J., & Drentea, P. (2006). InCharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: Development, administration, and score interpretation. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 17, 34-50.

Portuguese Observatory of Health Systems. (2014). Relatório de primavera 2014 [Spring report 2014]. Accessed from Sistemas de Saúde. Retirado de http://www.observaport.org/sites/observaport.org/files/RelatorioPrimavera2014.pdf [ Links ]

Santos, L., Pais-Ribeiro, J., & Guimarães, L. (2003). Estudo de uma escala de crenças e de estratégias de coping através do lazer. Análise Psicológica, XXI, 441-451. [ Links ]

Sargent-Cox, K., Butterworth, P., & Anstey, K. (2011). The global financial crisis and psychological health in a sample of Australian older adults: A longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 73, 1105-1112. doi: 10.1016/j.socsimed.2011.06.063 [ Links ]

Sociedad Española de Salud Pública y Administración Sanitária. (2011). Comunicado de la sociedad española de salud pública y administración sanitaria (sespas): El impacto en la salud de la población de la crisis Económica y las políticas para abordala [Statement from the Spanish society of public health administration (sespas): The impact of the economic crisis on the populations’ health and the politics to face it]. Barcelona, España: SESPAS.

Statistics Portugal. (2014). Estatísticas do emprego: 2º trimestre de 2014 [Employment statistics: 2nd quarter of 2014]. Statistics Portugal, 1, 1-9. [ Links ]

Stein, C., Hoffmann, E., Bonar, E., Leith, J., Abraham, K., Hamill, A., . . . Fogo, W. (2013). The United States economic crisis: Young adults’ reports of economic pressures, financial and religious coping and psychological well-being. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34, 200-210. doi: 10.1007/s10834-012-9328-x

Torres, F. (2009). Back to external pressure: Policy responses to the financial crisis in Portugal. South European Society and Politics, 14, 55-70. doi: 10.1080/136008740902995851 [ Links ]

Yurtsever, S. (2011). Investigating the recovery strategies of European Union from the global financial crisis. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 687-695. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.132 [ Links ]

A correspondência relativa a este artigo deverá ser enviada para: Saúl Neves Jesus, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais (FCHS) – Universidade do Algarve, Campus de Gambelas, Edifício 1, 8005-139 Faro, Portugal. E-mail: snjesus@ualg.pt

Submissão: 28/07/2015 Aceitação: 07/02/2016