Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Psicológica

versão impressa ISSN 0870-8231versão On-line ISSN 1646-6020

Aná. Psicológica vol.36 no.3 Lisboa set. 2018

https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1242

The experiences in the family of origin and the early maladaptive schemas as predictors of marital violence in men and women

As experiências na família de origem e os esquemas inicias desadaptativos na violência conjugal em homens e mulheres

Kelly Cardoso Paim1, Denise Falcke1

1Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos – UNISINOS, São Leopoldo, Brasil

ABSTRACT

Marital violence is a worldwide issue that affects several economic, racial and ethnic groups. Assuming that the marital violence dynamics is interactive, this study aims to identify the predicting variables of the phenomenon, through the perspective of the Theory of Schemas by Jeffrey Young. This way, the importance of experiences within the family of origin as well as the Early Maladaptive Schemas predicting marital physical violence between men and women were investigated. There was a sample made up of 181 men and 181 women and the instruments applied for data collection were: Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ-S3) and Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2). The analysis of the results was carried out through multiple regression analysis with the stepwise methodology. The results show that the defectiveness/shame schema in both men and women and the mistrust/abuse schema in men are predicting variables of the violence committed against the spouse. A longer adjustment in mothers was considered the protective variable of violent behaviors among women. Regarding the victimization of the violence, the defectiveness/shame schema in both men and women and the Mistrust/Abuse schema in men are predicting variables of the violence suffered in the intimate relationships. More functionality in the decision-making styles of mothers was identified as a violence-victimization protector among women. The outcome of this study amplifies the discussion on the variables which can identify the marital violence phenomenon, consolidating the importance of the Early Maladaptive Schemas in the marital violence.

Key words: Marital violence, Early maladaptive schemas, Marital relationships.

RESUMO

A violência conjugal é uma problemática mundial que abrange diferentes classes econômicas, raças e etnias. Partindo-se do pressuposto de que a dinâmica conjugal violenta é um fenômeno complexo e interacional, o presente estudo se propõe a identificar variáveis preditoras do fenômeno, utilizando a perspectiva da Teoria dos Esquemas de Jeffrey Young. Sendo assim, foi investigado o poder das experiências na família de origem e dos Esquemas Iniciais Desadaptativos como preditores da violência física cometida e sofrida na relação conjugal conforme o sexo. A amostra foi constituída por 181 homens e 181 mulheres e os instrumentos utilizados para a coleta de dados foram: Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ-S3), e Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2). A análise dos resultados foi realizada através de análise de regressão múltipla com método stepwise. Os resultados indicaram que o esquema de defectividade/vergonha das mulheres e dos homens e o esquema de desconfiança/abuso dos homens são variáveis preditoras da violência física cometida contra o cônjuge. O maior ajustamento materno foi considerado a variável protetiva de comportamentos violentos cometidos pelas mulheres. Em relação à vitimização da violência, os esquemas de desconfiança/abuso das mulheres e dos homens, assim como o esquema de defectividade/vergonha dos homens foram identificados como preditores de violência física sofrida nos relacionamentos íntimos. A maior funcionalidade do estilo de decisão materno foi identificada como protetor de vitimização de violência para as mulheres. Os achados ampliam a discussão sobre as variáveis que podem explicar o fenômeno da violência conjugal, consolidando a importância da avaliação dos Esquemas Iniciais Desadaptativos em situação de violência conjugal.

Palavras-chave: Violência conjugal, Esquemas iniciais desadaptativos, Relacionamento conjugal.

The intergenerational transmission of marital violence is widely accepted and confirmed in several investigations (Fang & Corso, 2007, 2008; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2006; Godbout, Dutton, Lussier, & Sabourin, 2009; Kerley, Xu, Sirisunyaluck, & Alley, 2010; Milner et al., 2010; Pournaghash-Tehrani & Feizabadi, 2009; Wang, Horne, Holdford, & Henning, 2008; Wareham, Boots, & Chavez, 2009; Weisbart et al., 2008). Research indicates that a violent environment within the family is a risk factor for mental health problems in children and adolescents (Anderson & Bang, 2012; Sá, Bordin, Martin, & Paula, 2010). Authors also emphasize that the exposure to abuse and experience of unstable relationships in childhood threatens the confidence for relationships of attachment and results in maladaptive models of belief about themselves, about others and about relationships, creating weak attachment bonds along their lives (Cecero & Young, 2001; Platts, Mason, & Tyson, 2005; Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, 2003).

People who grow up in a violent environment may have different psychopathological conditions throughout their development (Caballo, 2007). Recent research confirms that maltreatment suffered during childhood is considered the main predicting factor for the development of Personality Disorders (Cohen et al., 2013; Hengartner, Ajdacic-Gross, Rodgers, Müller, & Rössler, 2013). In a study involving criminals carried out in Toronto, Canada, Kolla et al. (2013) identified a strong influence of physical abuse during childhood in the development of persistent reactive aggression throughout life. Hengartner et al. (2013), in their study with 512 participants in Zurich, using multivariate analysis, also found physical abuse to be a predicting variable of Antisocial Personality Disorder. In the same sense, Cohen et al. (2013), in a study in the United States involving 156 non-psychotic psychiatric patients, concluded that emotional abuse is related to more severe personality psychopathy.

Thus, experiencing violence within the family of origin, suffering and witnessing parental aggression have been pointed out as some of the greatest predictors of personality and development disorders, besides increasing the predisposition to marital aggression (Boyle, O’Leary, Rosenbaum, & Hassett-Walker, 2008; Kernsmith, 2006). On the other hand, some authors question the idea of linearity and determinism between the violence experienced within the family of origin and the perpetuation in violent relationships during their adult lives. Low rates in the cause and effect relationship between the past and current experiences, found in some studies, suggest that other variables can explain the perpetuation of the marital violence event (Delson & Margolin, 2004; Stith et al., 2000).

Even though the repetition of violent standards among generations is observed in several studies, the dynamics of the perpetuation of violence is still unclear, since many people who are abused during childhood do not become aggressors, which makes the cause-effect determinist perspective questionable. In this sense, the existence of mediating variables between the experiences within the family of origin and the marital violence can be considered, including the Early Maladaptive Schemas as proposed by Young (Young et al., 2003). Based on this assumption, this study was aimed at identifying, in addition to the experiences in the family of origin, the predictive power of Early Maladaptive Schemas in marital violence.

Abuse experience in the primary relationships and the development of early maladaptive schemas

The early relationship experiences in the structuring of the personality are highlighted by Young (1990). The author extends the model of cognitive-behavioral therapy schemas by Aaron Beck, and considers the existence of Early Maladaptive Schemas (EMS) as rigid, broad, lasting and dysfunctional interpretative structures that cause functional damage to individuals, mainly in relation to interpersonal relationships (Cecero & Young, 2001). The theory proposes that current daily situations activate memories, emotions, bodily sensations and childhood related cognitions from harmful experiences during childhood, generating kinds of maladaptive functioning (Young et al., 2003). According to the author, the EMS are behind the maladaptive behaviors, which are just maladaptive coping responses used in the face of schema activation.

Accordingly, Young (1990) proposes that, for a healthy personality structuring, some emotional needs related to children’s development must be satisfied: safe bond; autonomy, competence and feeling of identity; freedom of expression and validation of needs and emotions; spontaneity and leisure; realistic limits and self-control. Thus, the primary relationships and early experiences that do not meet these needs, combined with the innate temperament of the child and traumatic events, explain the origin of the EMS (Young et al., 2003). McCarthy e Lumley (2012) contribute to the understanding of the relationship between maltreatment during childhood and the development of EMS, and the study also considered as variables other forms of abuse throughout life. The results of the research with 97 Canadian university students highlighted that maltreatment during childhood is responsible for both the development of unconditional (primaries) and conditional EMS (later created as coping strategies for the activation of the primary EMS). In order to understand the relationship between emotional abuse/emotional negligence and anxiety, depression and dissociation symptoms, as well as EMS, in relation to university students in the United States, Wright, Crawford and Del Castilho (2009) used a multivariate regression analysis with a sample of 301 university students of both genders. The results revealed that the perceptions of abuse and emotional negligence during childhood have an influence on emotional symptoms later, and the EMS were identified as mediating variables between the experiences during childhood and the emotional symptoms during adult life. Therefore, the study suggests that the way that the university students internalized childhood experiences may be even more important than the events themselves, and that the EMS have a long term impact on the lives of the subjects.

The choice of the intimate partner and marital interaction may occur in a way that contributes to the maintenance of people’s EMS (Young et al., 2003), and these negative interactions between the couple may contribute to a violent relationship (Paim, Madalena, & Falcke, 2012). Based on this, the maladaptive coping styles used in the face of the schema activation, which usually happens by reliving the emotions or situations that were familiar or stressful in the past, activate the schemas of the partner, causing the schematic cycle of the couple (Behary & Young, 2011).

The early maladaptive schemas and the marital violence

Studies highlight that the first domain schemas (Disconnection and Rejection) are present in the violent interpersonal functioning (Calvete, Estevez, & Corral, 2007; Crawford & Wright, 2007; Khosravi, Attari, & Rezaei, 2011; Paim et al., 2012). This can be explained by the fact that the first domain describes people who have difficulties to maintain strong bonds (Young et al., 2003). The constant feeling of frustration in relation to the expectations of security, empathy and acceptance can result in maladaptive coping responses, including the victimization and perpetration of violence in the intimate relationships (McGinn & Young, 2012; Paim et al., 2012).

With the main objective of testing a model in which the first domain schemas were mediating variables between psychological abuse during childhood and interpersonal conflicts in relation, Messman-Moore and Coates (2007) carried out an investigation with 382 female university students in the United States. The results showed that the relationship between psychological abuse during childhood and interpersonal conflicts was mediated by three first domain schemas: mistrust/abuse, defectiveness/shame and abandonment. Based on this, the study suggests that there is a lasting impact of psychological abuse and that the effects of psychological violence persist through the EMS of the first domain schema. Similarly, the study by Khosravi et al. (2011), conducted in Iran, showed that the experiences of abuse in the primary relationships were associated with marital violence cases, and the majority of women had suffered some kind of childhood abuse. In addition, the researchers indicated that the most common schemas identified in these women were: emotional deprivation, mistrust/abuse and defectiveness/shame, all belonging to the first domain.

The literature review reveals that the EMS of the first domain are mostly associated with the maintenance of violent relationships. Especially the mistrust/abuse schema has shown clear importance in understanding violent behaviors in intimate relationships. Studies carried out in different countries, such as Brazil, Spain, the United States and Iran have shown to be unanimous in relation to the presence of this schema in marital violence (Calvete et al., 2007; Khosravi et al., 2011; Messman-Moore & Coates, 2007; Paim et al., 2012). The belief that other people are not trustworthy and will intentionally harm them is activated and maintained in the relationships. The aggressive and abusive behaviors on the part of people, as well as the victimization of abuse in the relationships, may be strategies to maintain this schema (McGinn & Young, 2012).

In the study by Paim et al. (2012), conducted in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, the mistrust/abuse schema was associated both with the perpetration and the victimization of marital violence and the authors view marital violence as a maladaptive schema strategy to deal with the emotional schema activation. Thus, the results refer to the understanding of marital violence as an event in which the positions of the victim and aggressor are not necessarily static, and the same individual can assume both positions.

The bi-directionality of marital violence has been defended by many authors (Bates, Graham-Kevan, & Archer, 2013; Bernards & Graham, 2013; Falcke, Oliveira, Rosa, & Bentancur, 2009; Oliveira & Souza, 2006; Strauss, 2008). Strauss (2008), through an important research about physical marital violence involving 13,601 university students of 32 countries, obtained results that also go against the belief that physical violence in intimate relationships is entirely committed by only one aggressor, because the bidirectional physical marital violence was the most prevalent. In the same research, the author also questions the male domination as the violence etiology in intimate relationships. The results showed that the domination, both male and female, was associated with an increase in violence, and there was no difference between the genders.

Although some studies reinforce the perspective that marital violence goes beyond a matter of gender, indicating the existence of a violent marital dynamics, the violence suffered by men is still rarely studied (Falcke et al., 2009). Thus, this study proposes to evaluate the predictive power of the experiences in the family of origin and of the Early Maladaptive Schemas of first domain schema in marital violence, considering the violence committed and suffered by men and women.

Method

Participants

The study had 362 participants, 181 male and 181 female, selected by the convenience criteria in the format “snowball”. All the participants lived in the metropolitan area of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, and were officially married or in a de facto relationship for at least six months.The age of the participants ranged from 19 to 81 years, with an average of 41.17 years (SD=12.75). Most of them had completed higher education (45.9%), performed some remunerated activity (81.5%) and had never been married before (78.5%).

Instruments

Sociodemographic Data Questionnaire: Closed questionnaire, consisting of 23 questions, with the purpose of obtaining the sociodemographic data of the participants. Age, educational level, occupation, income and time in the current relationship are some items that compose the questionnaire.

Subscales of Family Background Questionnaire (FBQ): The FBQ (Melchert, 1998) is a closed questionnaire containing 179 items to be responded on a five-point Likert scale, aimed at obtaining an overall value of the functionality of the family of origin. It has 15 subscales that encompass several variables that have been identified as potentially important in child development. For this study, the following subscales were Sexual Abuse is the perception of any sexual contact by the father, mother, siblings, other family members or other people; Physical Neglect is the lack of physical care (food, clothing, hygiene conditions etc.); Physical Abuse refers to the memories about physical aggressions by the parents against the child; Decision-Making Style is the coherence of the parents’ attitudes towards their children, from which the emotional environment of safety, trust and stability is created. The ability to listen and understand is also contemplated; Psychological Adjustment refers to the mental health of the parents (including especially mood disorders, substance abuse and violence); Substance Abuse is related to the memories about the consumption of alcohol and other drugs by the parents and the consequent behavioral changes. Parental Coalition is the degree of agreement between the father and the mother in relation to the rules or instructions to their children, and also considers the couple’s conflict resolution ability. The study was translated and adapted for the Portuguese language by Falcke (2003), showing good construct validity and internal consistence. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained for each subscale was: 0.864 for father physical abuse, 0.799 for mother physical abuse, 0.295 for sexual abuse, 0.776 for physical neglect, 0.876 for father decision making style, 0.876 for mother decision making style, 0.937 for father substance abuse, 0.877 for mother substance abuse, 0.783 for father psychological adjustment, 0.706 for mother psychological adjustment, 0.865 for parental coalition. The rates show good reliability of the subscales, with exception of the sexual abuse subscale, which can be explained by the fact that it contains questions that include the abuse by different members of the family and other people. Thus, as it is expected that the sexual abuse is committed by specific offenders, a low internal reliability rate is understandable. It is important to note that, although some names of the dimensions indicate the negative variable, the scale is scored in the direction of functionality of the family of origin, that is, the higher the scores, the lower the occurrence of these variables.

Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ-S3): The YSQ – S3 (Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, 2003) in the reduced version, composed of 90 items, evaluates 18 Early Maladaptive Schemas that are mapped by the sum of the results of each group of five questions. The schemas are classified into five large domains. This classification emerged from the clinical experience of the author, and was refined in subsequent empirical studies. Most of the findings related to the Young Schema Questionnaire show favorable results concerning the internal consistence of the scale and the discriminative sensitivity, taking into account the differences between clinical and non-clinical groups (Cazassa & Oliveira, 2008). The version used in this study was translated and adapted to the Portuguese language by Rijo and Pinto Gouveia (1999). Only the dimensions of the instrument corresponding to the domain schemas Disconnection and Rejection were used, since such schemas are the ones that are being the most associated with violent behaviors in the interpersonal relationship in previous studies (Crawford & Wright, 2007; Khosravi et al., 2011; Paim et al., 2012). Following is a brief description of the schemas that compose the Disconnection and Rejection domain: Emotional Deprivation contemplates beliefs of emotional neglect, including negative expectation in relation to the satisfaction of the emotional support needs by the partner; Abandonment is characterized by insecurity in relation to the stability of the relationships and constant expectation of abandonment; Mistrust/abuse corresponds to the beliefs that relationships are dangerous and abusive, including constant expectations of being deceived, betrayed, or hurt by the partner. Social isolation is characterized by the feeling of not belonging to a group, community or loving relationship, with beliefs of being different from other people. Defectiveness/shame includes beliefs of being defective, undesirable, inferior, and, as a result, undeserving of the love and appreciation by the partner. In addition, there is hypersensitivity to criticism, insecurity, as well as shame and self-accusatory attitude.. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained for the Jeffrey Young’s Schema Inventory was 0.962, indicating excellent reliability. When the specific coefficients of the dimensions used were considered, the following internal reliability rates were obtained: 0.779 for abandonment, 0.790 for emotional deprivation, 0.752 for mistrust/abuse, 0.789 for social isolation and 0.800 for defectiveness/shame.

Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): The CTS2 was conceived by Strauss, Hamby, Boney-McCoy and Sugarman (1996), and contains, in total, 78 items that describe possible actions of the respondent and, mutually, of their partner. The instrument is composed of five scales that represent the following dimensions: (1) physical violence; (2) psychological aggression; (3) sexual coercion; (4) injury; (5) negotiation. In this study, only the physical violence subscale was used, which is divided into severe and minor physical violence. Strauss (2008) considered minor aggressions (pushing, grabbing, slapping, throwing object, twisting the arm and pulling the hair), and severe (punching, hitting, kicking, throwing against the wall, burning or scalding, using a knife as a weapon). It is important to note that the perceptions of the subjects about their violent behaviors committed against their partners (committed violence) and also their perception about the violence committed by their partners (suffered violence) were considered. This was adapted to the Portuguese language by Moraes, Hasselmann and Reichenheim (2002). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained for the physical violence dimension was 0.832, indicating good reliability.

Data collection procedure

The questionnaires were responded at the subjects’ homes or at a more adequate place indicated by them. Even if the instruments had been self-applicable, a member of the research team was present during the application in order to clarify possible questions. The larger project, titled “Predicting Variables of Marital Violence: Experiences within the family of origin, personal and correlational characteristics”, which the present study is a part of, was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of the Unisinos and approved under registration number 11/129. The research complied with the ethical recommendations for studies involving human beings, according to the orientations of Resolution 196/1996 of the National Health Council.

Data analysis procedures

The data were analyzed through the program Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), version 20.0. The descriptive analyses (average, standard deviation and percentages) were performed for the characterization of the sample. In addition, the multiple regression analysis (stepwise method) was performed to evaluate which experiences within the family of origin and the EMS of the Disconnection and Rejections domain could be considered as predictors of marital physical violence committed against and suffered by the intimate partner. The dependent variables (committed and suffered physical violence) and the independent variables (experiences in the family of origin and Disconnection and Rejection EMS domain) were separately analyzed for men and women.

Results

The overall committed physical violence, considering people’s own evaluation, was identified in 23.6% among women and 27.3% among men. When the suffered overall physical violence is considered, also taking into account the evaluation of the subject, the rates were 21.4% for women and 26.2% for men. No significant differences were found between the sexes (p>0,05).

The multiple regression analysis (Stepwise method) evaluated which experiences within the family of origin and EMS were predictors of committed and suffered violence by men and women. The scores of the FBQ scale (experiences within the family of origin) indicate functionality within the family, so even if some of the dimension names indicate a negative dimension, the higher the scores, the lower the presence of this variable Multicollinearity indicators in all models were acceptable (VIFs bellow 3,39).

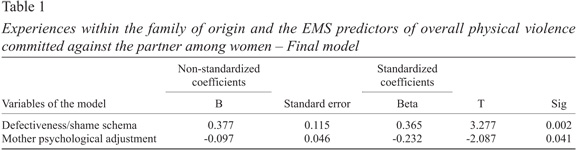

Considering the data of the female sample, the defectiveness/shame schema was shown to be predictor of physical violence committed by women and the experience of greater maternal psychological adjustment was identified as a protecting variable of physical violence committed by women (Table 1). Such procedure provided a coefficient of explained variance (R2) of 0.203, which determines that these variables explain 20.3% of the physical violence committed by women.

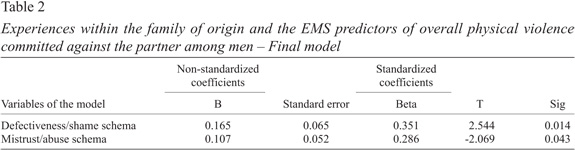

In the case of the male sample, the defectiveness/shame and mistrust/abuse schemas were the predicting variables of physical violence committed by men (Table 2), obtaining a coefficient of explained variance (R2) of 0.335, explaining 33.5% of the violence committed by them.

The defectiveness/shame schemas of women (β=0.365 and p=0.002) and men (β=0.351 and p=0.014), as well as the mistrust/abuse schema of men (β=0.286 and p=0.043), can be considered predicting variables of physical violence committed against the intimate partner. The subjects that had these schemas obtained higher rates of overall physical violence committed in the marital relationship. The experience of greater maternal psychological adjustment of the women (β=-0.32 and p=0.041) was the only protecting variable of violent behaviors against the partner in the marital relationship.

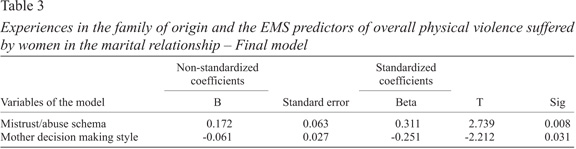

Taking into consideration the overall physical violence suffered in the intimate relationship, the mistrust/abuse schema was shown to be predictors of physical violence suffered among women and the experience of better maternal decision making style was identified as protecting variable of the physical violence suffered by women (Table 3). This model provided a coefficient of explained variance (R2) of 0.188, which determines that these variables explain 18.8% of the physical violence suffered by women.

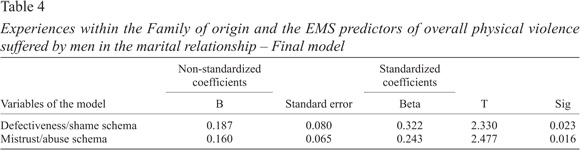

The defectiveness/shame and mistrust/abuse schemas were the predicting variables of physical violence suffered by men in the marital relationship (Table 4), obtaining a coefficient of explained variance (R2) of 0.364, which explained 36.4% of the physical violence suffered by them.

The mistrust/abuse schemas of women (β=0.311 and p=0.008) and men (β=0.343 and p=0.016), as well as the defectiveness/shame schema of men (β=0.322 and p=0.023), can be considered predicting variables of physical violence suffered in the marital relationship. The subjects with these schemas revealed to suffer more physical violence in the marital relationship. A more functional maternal decision making style (β=-0.251 and p=0.031) was the only protective variable in relation to the violence suffered in the marital relationship, concerning women.

Discussion

In the studied sample, there was no significant difference between the rates of suffered and committed violence by men and women, which reinforces the view that, understanding the marital violence only as a gender issue is limited. When the overall physical violence committed against the partner in the current relationship is considered, the rates of 23.6% among women and 27.3% among men were found. When the overall physical violence suffered is considered, the rates were 21.4% among women and 26.2% among men. Such findings are similar to studies that contradict the view that men are always the aggressor and women the victim (Bates et al., 2013; Bernards & Graham, 2013; Falcke et al., 2009; Oliveira & Souza, 2006), since a high rate of women admitted committing physical violence against their partners and more men than women perceived suffering violence in the relationship.

The levels of variance explained in relation to the marital violence suffered and committed by men and women express that the EMS are variables with important explanatory power of the event. Two schemas of the Disconnection and Rejection domain were identified as predictors of the physical violence in the marital relationship (mistrust/abuse and defectiveness/shame), explaining the perpetration of violence and victimization.

The results indicate the mistrust/abuse schema as predictor of physical violence victimization in the marital relationship of both men and women. Therefore, the individuals that developed the mistrust/abuse schema are the more likely to suffer physical abuse from their partners. Based on this, it is possible to understand that the EMS explains the maintenance of the abusive experiences in the current relationships, confirming previous researches that also identified this schema as an essential variable for the understanding about marital violence victimization (Crawford & Wright, 2007; Khosravi et al., 2011; Paim et al., 2012).

According to Young (1990), people tend to perpetuate their schemas, that is, they think and act in order to keep them functioning. The basic mechanisms of perpetuation of the schemas, proposed by the author, can explain the association between the mistrust/abuse schema and the physical violence victimization in intimate relationships. Thus, the establishment of a standard relationship in which a person becomes victim of physical violence may be related to maladaptive coping responses of surrender to the schema. So, the beliefs of the schema trigger an emotional and behavioral standard in a manner to relive childhood experiences responsible for their formation. Young et al. (2003) highlight that, people with mistrust/abuse schema tend to choose aggressive partners, who treat them as their abusive fathers or mothers. Furthermore, when using this coping response, they relate to others passively and complacently, perpetuating the belief that other people are untrustworthy and will hurt them.

The mistrust/abuse schema was also identified as predictor of physical violence committed by men in the marital relationship. Some previous studies also indicate such schema as being a variable associated with aggressive behaviors in the intimate relationships (Calvete et al., 2007; Paim et al., 2012). The feeling of insecurity, as well as the belief that other people are untrustworthy, dangerous and abusive, may generate defensive coping responses in the relationships (McGinn & Young, 2012). According to Young (1990), one of the maladaptive coping styles is the overcompensation of the schema, that is, they start to commit abusive as a way of feeling protected and less vulnerable to abusive experiences. It is a primitive children’s attempt used to relieve and cope with the pain resulting from early maltreatment; however, it becomes extreme and dysfunctional in adulthood and serves to maintain the schema. Therefore, the aggressions against the partner can be considered as part of processes of the schema, since there are usually traumatic experiences in its development, which tend to recur in adulthood in self-destructive relationships (Young & Behary, 1998).

The absence of the mistrust/abuse schema among the predicting variables of the perpetration of physical violence by women suggests that, among them, this schema is experienced and maintained with maladaptive coping responses of surrender and not with responses of overcompensation. In the study of Khosravi et al. (2011), with female victims of violence by their intimate partners in Iran, the authors also found the mistrust/abuse schema among the participants. Similarly, the study of Calvete et al. (2007), also with female victims of marital violence, first domain schemas were found as explanatory variables, among them the mistrust/abuse schema. Based on the findings of the present study, it is possible to understand that the overcompensation style of the mistrust/abuse schema is more used by men than women, who seem to experience more the surrender responses and assume the victim’s role.

The results also showed that the defectiveness/shame schema explained the physical violence committed against the intimate partner by men and women. Such schema involves beliefs of undesirability, inferiority and worthlessness, causing people to feel they are not worthy of love and, as a result, are rejected, criticized and excluded (McGinn & Young, 2012). The hypersensitivity to criticism and the intense fear of being rejected may explain the aggressive reaction against the intimate partner. Therefore, the constant feeling of danger triggers a series of defensive coping responses, among them the violence. It is possible to understand the violence against the intimate partner as an inability to deal with emotional activations resulting from the defectiveness/shame schema, and this is also suggested in other studies (Messman-Moore & Coates, 2007; Paim et al., 2012).

Concerning the perception of physical violence suffered in the marital relationship, the defectiveness/shame schema was only predictive in relation to men. When the defectiveness/shame schema is activated in women, they seem to be more the aggressors than the victims. Results of previous studies associate the victimization of the violence with this women’s schema (Calvete et al., 2007; Khosravi et al., 2011), but these studies did not consider the violence committed by women. Therefore, it is possible to confirm that this schema is present among women who are part of violent relationships and that the marital violence dynamics causes a complementarity of the victim and aggressor roles. Men with defectiveness/shame schema, besides performing physical violence against their wives, also maintain experiences in which they see themselves as victims of physical violence in the marital relationship. The maladaptive coping responses of surrender of the defectiveness/shame schema is to choose critical, rejecting partners, who make them feel diminished (Young et al., 2003), which can explain the choice of abusive partners and maintenance of dysfunctional relationships. The view about themselves as unworthy of love and appreciation can cause an acceptance of a passive position in the face of physical abuse. Furthermore, the intense fear of feeling rejected and criticized may make it hard to break up the violence cycle. Viewing female violence as more acceptable and feeling embarrassed with this situation can also justify the maintenance of a victimization pattern among men with defectiveness/shame schema.

The schema interaction in the relationships can explain the violent marital dynamics (Paim et al., 2012), and self-perpetrated standards of destructive responses, in the face of schema activation, also activate the EMS of the partner, with cognitive, emotional and behavioral responses equally destructive, establishing the maladaptive interaction between the couple. It is important to note that the schema of men were the same, both in relation to the victimization and perpetration of the violence, reinforcing the perspective of authors who view physical violence in the relationships as a bidirectional dynamic (Bates et al., 2013; Bernards & Graham, 2013; Falcke et al., 2009; Oliveira & Souza, 2006; Strauss, 2008). These authors contradict the idea that there is always an aggressor and a victim and suggest a position exchange that ends up maintaining a cycle of violence. Thus, it is possible to believe that the maladaptive coping responses define a position of victim or aggressor, and the same person can use the three coping styles (surrender, overcompensation or avoidance) (Young et al., 2003).

Even if the schema of women who suffer violence and those who commit it had been different, these were not different from the schema of men involved in violence. With this in mind, there is a need for a perspective that goes beyond the gender issue and seeks to understand the violent marital dynamics, and this perspective was already defended by some authors (Falcke et al., 2009; Oliveira & Souza, 2006; Strauss, 2008). Young (1990) highlights that the choice of partner and the interaction with them are mediated by the EMS. The results of the present study show that the violent marital dynamics is working towards the maintenance of first domain personality schemas, particularly the mistrust/abuse and defectiveness/shame schemas. Therefore, the marital violence is part of the schema maintenance process and the establishment of an abusive and unstable relationship repeats the experience of an already familiar standard in the primary relationships.

The greatest family functionality in terms of maternal psychological adjustment was shown to be protective in relation to violent behaviors by women against their partners. This result is in line with perspectives that indicate the experiences of unstable relationships during childhood as a threat to the security of the attachment relationships throughout life (Cecero & Young, 2001; Platts et al., 2005; Young et al., 2003). The emotional stability of the main caregiver is emphasized as an essential variable to meet the first emotional development need of children, which is the secure bond (Young et al., 2003).

The greatest functionality of maternal decision making style as protecting variable of physical violence victimization in the intimate relationship reinforces the importance of the mother’s functionality, who is generally the main caregiver, so women to establish non-violent intimate relationships. The decision style corresponds to the coherence of attitudes towards their children, from which the secure, reliable and stable emotional environment is created. This dimension also includes the ability to listen, understand and validate the emotional needs of the child. Therefore, to have trust and security in relation to the mother’s attitudes, and to be validated in their needs, makes women able to seek relationships in which they do not suffer physical violence.

The importance of the stability of the main caregiver as a protecting variable of violent relationships can also be explained by the importance of a stable functioning model that can relate in a healthy way. Young et al. (2003) state that the observation of models by children is also an important component in the structure of personality schemas. Based on the findings of the present study, it is possible to raise an assumption that women tend to be more benefited by maternal stability concerning the marital physical violence.

In the results obtained in this sample, physical abuse during childhood did not have predictive power for violent marital relations during adulthood, which goes against authors who suggest that children who suffer physical abuse during childhood repeat violent relationships in their adult lives Godbout et al., 2009; Kerley et al., 2010; Milner et al., 2010; Pournaghash-Tehrani & Feizabadi, 2009; Wang et al., 2008; Wareham et al., 2009; Weisbart et al., 2008). Therefore, it is possible to understand that other variables may interfere with this cause and effect relationship and among them are the mistrust/abuse and defectiveness schemas, and this is also suggested by other authors (Calvete et al., 2007; Messman-Moore & Coates, 2007; Wright et al., 2009). An environment where there is physical abuse during childhood also shows to have a great influence on the formation of personality schemas, which is confirmed in other researches (Cecero & Young, 2001; McCarthy & Lumley, 2012; Platts et al., 2005). However, it is important to note that the children’s temperament, trauma due to situational stressors and other significant relationships (with family, teachers, friends and other) can also influence the formation of the EMS, as well as protect them from their consolidation (Young et al, 2003). Thus, these results suggest that growing up in an abusive and unstable environment cannot be regarded as decisive for the physical violence victimization in the marital relationship. However, this environment may encourage the development of EMS that provide that people are more likely to maintain relationships in which they suffer physical abuse by their partner.

Final considerations

The present study confirms studies that contradict the idea of static roles by aggressors and victims, since there was no significant difference between the rates of violence suffered and committed by men and women. Thus, in the sample studies, it is possible to confirm the view of authors who understand the physical violence in relationships as a bidirectional dynamics, as an exchange of positions that ends up maintaining the cycle of violence.

Based on the results obtained, the EMS predictors of marital physical violence were identified. The important explanatory power of the variables meets the theory of Young (1990), who proposes that the schema interaction in the relationships can explain the violent marital dynamics, and the search for the maintenance of schemas may establish the maladaptive interaction between the couple.

The mistrust/abuse and defectiveness/shame schemas were predictive considering both the victimization and the perpetration of the marital physical violence among men. So, it is possible to believe that the coping styles define the position of victim or aggressor. In addition, although the schemas of women who suffer violent and those who commit it have been different, they were not different from the schemas of men in a violent situation. Therefore, it is also possible to consider that the violent marital dynamics is working towards the maintenance of first domain personality schemas, particularly the mistrust/abuse and defectiveness/shame schemas.

Based on the Theory of Young (1990), the coping styles, used in the process of schema, underlie the explanation about the behaviors that maintain the violent marital dynamics. The search for the confirmation of the schema makes people repeat their childhood experiences, using maladaptive coping responses of surrender and overcompensation. So, a kind of cycle of schema activation of childhood emotional, cognitive and behavioral responses establishes a destructive interaction between the couple.

The absence of variables of physical abuse suffered during childhood as predictors of a violent marital relationship at adult life suggests that the development of mistrust/abuse and defectiveness/shame schemas causes people to have more chances to maintain relationships in which they experience physical aggressions, expanding the understanding of studies that indicate the direct correlation of physical abuse in the primary relationships with the physical violence in intimate relationships. In contrast, the experiences of emotional stability of the mothers were shown to be protectors of future abusive relationships at adult life, showing that other variables in the primary relationships should be considered to understand the physical marital violence.

It is important to note that the present study did not consider other types of marital violence (psychological and sexual), and these could complement the understanding about the violent marital dynamics. In addition, the primary relationships with other caregivers were also not considered, which could have an intervenient effect in the results.

Finally, the results of the present study allow the development of psychotherapy intervention proposals with people going through marital violence, aimed at cognitive restructuring, especially focused on the weakening of mistrust/abuse and defectiveness/shame schemas. Furthermore, further studies are suggested about the effectiveness of the Schema Therapy in the context of marital violence, both in relation to individual or couple therapy.

References

Anderson, K., & Bang, E. J. (2012). Assessing PTSSD and resilience for females who during childhood were exposed to domestic violence. Child and Family Social Work, 17, 55-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00772.x [ Links ]

Bates, E. A., Graham-Kevan, N., & Archer, J. (2013). Testing predictions from the male control theory of men’s partner violence. Aggressive Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21499

Behary, B., & Young, J. (2011). Terapia dos esquemas para casais: Curando parceiros na relação. Material didático utilizado na III Jornada WP, Porto Alegre, Brasil. [ Links ]

Bernards, S., & Graham, K. (2013). The cross-cultural association between marital status and physical aggression between intimate partners. Journal of Family Violence, 28, 403-418. doi: 10.1007/s10896-013-9505-1 [ Links ]

Boyle, D. J., O’Leary, K. D., Rosenbaum, A., & Hassett-Walker, C. (2008). Differentiating between generally and partner-only violent subgroups: Lifetime antisocial behavior, family of origin violence, and impulsivity. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 47-55. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9133-8

Caballo, V. E. (2007). Manual para o tratamento cognitivo-comportamental dos transtornos psicológicos da atualidade. São Paulo: Santos. [ Links ]

Calvete, E., Estévez, A., & Corral, S. (2007). Intimate partner violence and depressive symptoms in women: Cognitive schemas as moderators and mediators. Behavior Research and Therapy, 45, 791-804. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.006 [ Links ]

Cazassa, M., & Oliveira, M. (2008). Terapia focada em esquemas: Conceituação e pesquisas. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica, 35, 187-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-60832008000500003 [ Links ]

Cecero, J. J., & Young, J. E. (2001). Case of Silvia: A schema-focused approach. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 11, 217-229. doi: 10.1023/A:1016657508247 [ Links ]

Crawford, E., & Wright, M. O. (2007). The impact of childhood psychological maltreatment on interpersonal schemas and subsequent experiences of relationship aggression. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 7, 93-116. doi: 10.1300/J135v07n02_06 [ Links ]

Cohen, L. J., Tanis, T., Bhattacharjee, R., Nesci, C., Halmi, W., & Galynker, I. (2013). Are there differential relationships between different types of childhood maltreatment and different types of adult personality pathology?. Psychiatry Research, 201, 234-243. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.10.036 [ Links ]

Delsol, C., & Margolin, G. (2004). The role of family-of-origin violence in men’s marital violence perpetration. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 99-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2003.12.001

Falcke, D. (2003). Águas passadas não movem moinhos? As experiências na família de origem como preditoras da qualidade do relacionamento conjugal. Tese de doutorado, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Portalegre, Brasil. [ Links ]

Falcke, D., Oliveira, D. Z., Rosa, L. W., & Bentancur, M. (2009). Violência conjugal: Um fenômeno interacional. Contextos Clínicos, 2, 81-90. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1983-34822009000200002&lng=pt&tlng=pt [ Links ]

Fang, X., & Corso, P. S. (2007). Child maltreatment, youth violence, and intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33, 281-290. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.06.003 [ Links ]

Fang, X., & Corso, P. S. (2008). Gender diferences in the connections between violence experienced as a child and perpetration of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 303-313. doi: 10.1007/s10896-008-9152-0 [ Links ]

Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2006). Examining the intergenerational transmission of violence in a New Zealand birth cohort. Child Abuse and Neglect, 30, 89-108. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.10.006 [ Links ]

Godbout, N., Dutton, D. G., Lussier, Y., & Sabourin, S. (2009). Early exposure to violence, domestic violence, attachment representations, and marital adjustment. Personal Relationships, 16, 365-384. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01228.x [ Links ]

Hengartner, M. P., Ajdacic-Gross, V., Rodgers, S., Müller, M., & Rössler, W. (2013). Childhood adversity in association with personality disorder dimensions: New findings in an old debate. European Psychiatry, 28, 476-482. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.04.004 [ Links ]

Kerley, K. R., Xu, X. H., Sirisunyaluck, B., & Alley, J. M. (2010). Exposure to family violence in childhood and intimate partner perpetration or victimization in adulthood: Exploring intergenerational transmission in urban Thailand. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 337-347. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9295-7 [ Links ]

Kernsmith, P. (2006). Gender differences in the impact of family of origin violence on perpetrators of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 21, 163-171. doi: 10.1007/s10896-005-9014-y [ Links ]

Khosravi, Z., Attari, A., & Rezaei, S. (2011). Intimate partner violence in relation to early maladaptive schemas in a group of outpatient Iranian women. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1374-1377. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.266

Kolla, N. J., Malcolm, C., Attard, S., Arenovich, T., Backwood, N., & Hodgins, S. (2013). Childhood maltreatment and aggressive behavior in violent offenders with psychopathy. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58, 487-494. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.05.005 [ Links ]

McCarthy, M. C., & Lumley, M. N. (2012). Sources of emotional maltreatment and the differential development of unconditional and conditional schemas. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 41, 288-97. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2012.676669 [ Links ]

McGinn, L. K., & Young, J. E. (2012). Terapia focada no esquema. In P. M. Salkovskis (Ed.), Fronteiras da terapia cognitiva (pp. 179-200). São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

Melchert, T. (1998). Testing the validity of an instrument for assessing family of origin history. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54, 863-875. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199811) [ Links ]

Milner, J. S., Thomsen, C. J., Crouch, J. L., Rabenhorst, M. M., Martens, P. M., Dyslin, C. W., . . . Merrill, L. L. (2010). Do trauma symptoms mediate the relationship between childhood physical abuse and adult child abuse risk?. Child Abuse and Neglect, 34, 332-344. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.017 [ Links ]

Messman-Moore, T. L., & Coates, A. A. (2007). The Impact of childhood psychological Abuse on adult Interpersonal conflict: The role of early maladaptive schemas and patterns of interpersonal behavior. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 7, 75-92. doi: 10.1300/J135v07n02_05 [ Links ]

Moraes, C. L., Hasselmann, M. H., & Reichenheim, M. E. (2002). Adaptação transcultural para o português do instrumento “Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2)” utilizado para identificar violência entre casais. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 18, 163-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2002000100017

Oliveira, D. C., & Souza, L. (2006). Gênero e violência conjugal concepções de psicólogos. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, 6, 34-50. http://www.revispsi.uerj.br/v6n2/artigos/pdf/v6n2a04.pdf [ Links ]

Paim, K., Madalena, M., & Falcke, D. (2012). Esquemas iniciais desadaptativos na violência conjugal. Revista Brasileira de Terapias Cognitivas, 8, 31-39. http://www.rbtc.org.br/detalhe_resumo.asp?id=155 [ Links ]

Platts, H., Mason, O., & Tyson, M. (2005). Early maladaptive schemas and adult attachment in a UK clinical population. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 78, 549-564. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16354444 [ Links ]

Pournaghash-Tehrani, S., & Feizabadi, Z. (2009). Predictability of physical and psychological violence by early adverse childhood experiences. Journal of Family Violence, 24, 417-422. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9245-4 [ Links ]

Rijo, D., & Pinto Gouveia, J. (1999). A new instrument for the assessment of early maladaptive schemas. [ Links ] Poster presented to the Society for Psychotherapy Research 30th Annual Meeting, Braga, Portugal.

Sá, D. G. F., Bordin, I. S., Martin, D., & Paula, C. S. (2010). Fatores de risco para problemas de saúde mental na infância/adolescência. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 26, 643-652. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722010000400008 [ Links ]

Stith, S. M., Rosen, K. H., Middleton, K. A., Busch, A. L., Lundeberg, K., & Carlton, R. P. (2000). The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 62, 640-654. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00640.x [ Links ]

Strauss, M. A. (2008). Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 252-275. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.10.004 [ Links ]

Strauss, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D. B. (1996). The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283-316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001 [ Links ]

Wang, M., Horne, S. G., Holdford, R., & Henning, K. R. (2008). Family of origin violence predictors of IPV by two types of male offenders. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 17, 156-174. doi: 10.1080/10926770802355915 [ Links ]

Wareham, J., Boots, D. P., & Chavez, J. M. (2009). A test of social learning and intergenerational transmission among batterers. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37, 163-173. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2009.02.011 [ Links ]

Weisbart, C. E., Thompson, R., Pelaez-Merrick, M., Kim, J., Wike, T., Briggs, E., . . . Dubowitz, H. (2008). Child and adult victimization: Sequelae for female caregivers of high-risk children. Child Maltreatment, 13, 235-244. doi: 10.1177/1077559508318392 [ Links ]

Wright, M. O., Crawford, E., & Del Castillo, D. (2009). Childhood emotional maltreatment and later psychological distress among college students: The mediating role of maladaptive schemas. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 59-68. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.007 [ Links ]

Young, J. E. (1990). Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A schema-focused approach. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press. [ Links ]

Young, J. E., & Behary, W. T. (1998). Schema-focused therapy for personality disorders. In N. Tarrier, A. Wells, & G. Haddock (Eds.), Treating complex cases: The cognitive behavioural approach (pp. 340-376). New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford Press.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Kelly Cardoso Paim, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos – UNISINOS, Av. Unisinos, 950, Cristo Rei, São Leopoldo, RS, 93020-190, Brasil. E-mail: kelly.paim@hotmail.com

This research was supported by FAPERGS.

Submitted: 05/03/2016 Accepted: 13/06/2017