Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Psicológica

versão impressa ISSN 0870-8231versão On-line ISSN 1646-6020

Aná. Psicológica vol.37 no.2 Lisboa jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1471

Prevalence and predictors of Burnout Syndrome among public elementary school teachers

Prevalência e preditores da Síndrome de Burnout entre professores do ensino básico público

Mary Sandra Carlotto1, Sheila Gonçalves Câmara2

1Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos – UNISINOS, São Leopoldo, Brasil

2Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre – UFCSPA, Porto Alegre, Brasil

ABSTRACT

Burnout is a psychosocial phenomenon, expression of several crises and disorientation in society, which has been subjecting the many labor sectors to too much tension over the years. The teaching profession is exposed, in the current work context, to a large amount of psychosocial stressors that, if persistent, may lead to Burnout. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to identify the prevalence and the predictors of the Burnout Syndrome (BS) in a random sample of 679 Brazilian teachers from 37 public elementary schools. The instruments were the Spanish Burnout Inventory; the Battery of Psychosocial Risk Assessment; and a questionnaire to assess sociodemographic and occupational variables. There was 7.5% prevalence of Profile 1 SB, and 18.3% of Profile 2 SB. Results point as predictors of Burnout dimensions the variables autonomy, conflict role, ambiguity role, overload, social support, and interpersonal conflicts. Results point predictor models of burnout dimensions composed of psychosocial risks derived from the type of the activity, and of interpersonal risks, with highlight to the variables social support and overload, which are present in all of the dimensions. Suggestions for further studies and implications on the practice are approached.

Key words: Burnout, School teachers, Occupational health.

RESUMO

Burnout é um fenómeno psicossocial, expressão de várias crises e desorientação na sociedade, o que tem submetido muitos setores laborais a grande tensão ao longo dos anos. A profissão docente está exposta, no contexto laboral atual, a uma grande quantidade de fatores de estresse psicossocial que, se persistentes, podem levar ao Burnout. O objetivo desse estudo transversal foi identificar a prevalência e os preditores da Síndrome de Burnout (SB) em uma amostra aleatória de 679 professores brasileiros de 37 escolas públicas de ensino básico. Os instrumentos foram o Spanish Burnout Inventory, a Bateria de Riscos Psicossociais e um questionário com variáveis sociodemográficas e laborais. Foi identificada uma prevalência de 7,5% para o Perfil 1 de SB e 18,3% para o Perfil 2 de SB. Os resultados indicaram como preditores das dimensões de Burnout as variáveis autonomia, conflito de papel, ambiguidade de papel, sobrecarga, suporte social e conflitos interpessoais. Os resultados demonstram modelos preditores das dimensões de Burnout compostos de riscos psicossociais derivados do tipo de atividade e dos riscos interpessoais, destacando as variáveis suporte social e sobrecarga, presentes em todas as dimensões. São apresentadas sugestões para estudos futuros e implicações para a prática.

Palavras-chave: Burnout, Professores de escola, Saúde ocupacional.

Introduction

Burnout Syndrome

The Burnout Syndrome (BS) is considered a chronic response to interpersonal stressors occurred in a work-related situation (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001; Leiter, Bakker, & Maslach, 2014). Burnout is a group of negative symptoms that a worker experiences in labor context (Zhou & Wen, 2007). According to the burnout theoretical model developed by Gil-Monte (2005), the illness is a psychological response to chronic work-related stress of interpersonal and emotional nature that appears in professionals of service-sector organizations who work in direct contact with clients or users.

Gil-Monte (2005, 2011) built a theoretical model in which he describes four dimensions: (1) enthusiasm toward the job, characterized by behaviors performed by workers toward their goals at work. They feel enthusiastic and involved with their work activities, deeming them rewarding and an important source of personal and professional pleasure. To characterize the syndrome, this dimension should be assessed in an inverse way, that is, low scores are indicative of high levels of Burnout; (2) psychological exhaustion, which is defined by the occurrence of emotional and physical exhaustion and is caused by interpersonal relationships in the work context. Workers interact daily with people who have or who cause problems; (3) indolence, dimension marked by negative attitudes in social interactions in the work context. Workers interact with people in an impersonal, indifferent and distant way, losing their ability to empathize with the problems presented by those they serve; and, (4) guilt, defined as a social emotion resulting from the attitudes and behaviors present in the indolence dimension. Workers evaluate their behaviors as if they were violating some type of code of ethics or norm derived from the prescription of their professional role. This feeling does not occur in all workers and it is this dimension that differentiates the two Burnout profiles.

Thus, based on the assessment of the BS dimensions, the theoretical model allows the construction of two differentiated profiles, Profile 1 and Profile 2 (Gil-Monte, 2005; Guidetti, Viotti, Gil-Monte, & Converso, 2017). Profile 1 is characterized by a set of feelings and behaviors linked to workplace stress, which impact on the wellbeing of workers. This discomfort does not incapacitate them for the professional exercise; however, it negatively affects productivity and the quality of their job. Professionals manage to keep working for a long time, adopting defensive strategies and justifying their lack of commitment with external factors.

Profile 2 presents the same characteristics as Profile 1 dimensions, in addition to the guilt dimension. Professionals affected by this profile blame themselves for feeling worn out and less physically and emotionally able to deal with labor demands and for withdrawal behaviors in interpersonal relationships at work. In this profile, professionals are aware that they are failing to fulfill their professional duties and the social expectations of their role, and are hard on themselves because of that, which triggers feelings of frustration and emotional suffering. Professionals affected by Profile 2 present serious problems in the execution of their job, greater cognitive, emotional and behavioral deterioration, with more work leaves (Rabasa, Figueiredo-Ferraz, Gil-Monte, & Llorca-Pellicer, 2016) and health problems (Diehl & Carlotto, 2014), the most frequent being depression (Gil-Monte, 2012).

The BS has been evidenced as an important epidemiological and public health matter, due to its negative impacts at individual, organizational and social levels (Gil-Monte, 2008; Leiter et al., 2014; Manzano-García & Ayala-Calvo, 2013; WHO, 2001). For its importance, there is an exponential growth in the amount of information gathered since studies started in the 1970’s (Manzano-García & Ayala-Calvo, 2013). Burnout is a psychosocial phenomenon, expression of several crises and disorientation in society, which has been subjecting the many labor sectors to too much tension over the years, especially assistance-oriented ones (Cebrià-Andreu, 2005). The several economic crises and the constant changes in labor conditions have made workers more vulnerable to developing BS. Teachers have been one of the most investigated occupational groups since the pioneering phase of studies about burnout (Carlotto & Câmara, 2008).

Burnout Syndrome in teachers

In the last few years, teachers have been facing several difficulties, such as increasing loss of their social status and purchase power resulting from low wages, overload, bad work conditions, lack of benefits, more bureaucracy, and for being the target of strong criticism by the society (Jani, 2017; Khosla, 2013; Mearns & Chain, 2003). The teaching profession is exposed, therefore, in the current work context, to a large amount of psychosocial stressors that, if persistent, may lead to Burnout (Guglielmi & Tatrow, 1998).

Psychosocial stressors have been affecting the health of teachers and making them vulnerable to Burnout (Khosla, 2013). The main stressors pointed in the literature are the students’ lack of interest and indiscipline (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017); lack of structure; lack of dialogue, and authoritarianism by both the coordination and the direction of the school; Disempowering policies and practices; individualism and competition among coworkers, and low wages (Costa & Rocha, 2013; Prilleltensky, Neff, & Bessell, 2016). Very often the current school reality makes teachers obliged to provide in poor conditions, a social assistance that goes beyond those related to education (Maranda, Viviers, & Deslauriers, 2014).

Studies carried out with teachers have evidenced association between burnout and overload, classroom demands (Brouwers, Tomic, & Boluijt, 2011; Carlotto, Dias, Batista, & Diehl, 2015; McCarthy, Lambert, O’Donnell, & Melendres, 2009; Masmoudi et al., 2016), ambiguity role (Farber, 1991) and conflict role (Konukman et al., 2010), autonomy (Olivier & Williams, 2005), social support (Brouwers et al., 2011; López, Bolaño, Mariño, & Pol, 2010), and interpersonal conflicts (Mercado-Salgado & Gil-Monte, 2010; Zhou & Wen, 2007).

Burnout in teachers has been receiving increasing attention from researchers and scholars, as its severity among education professionals has made teaching a high-risk job for the development of this syndrome (Guidetti et al., 2017; Stoeber & Rennert, 2008). Its occurrence affects the educational environment and the social environment, interfering with the achievement of pedagogical results and with the quality of education (Guglielmi & Tatrow, 1998; Klusmann, Kunter, Trautwein, Lüdtke, & Baumert, 2008), having been associated with reduced job satisfaction (Kroupis et al., 2017), reduced sense of teaching efficacy (Smetackova, 2017), the intention to quit teaching (Carlotto, 2012), absenteeism (Rabasa et al., 2016), and lower quality of personal life (Fernandes & Rocha, 2009).

Thus, it becomes relevant to perform studies that can identify Burnout prevalence and risk profile in order to intervene in and prevent this occupational pathology (Leiter et al., 2014; Maslach & Leiter, 2008). Based on the exposed, this cross-sectional, observational and analytical study aims to identify BS prevalence and the predictive power of psychosocial risks in a sample of Brazilian teachers.

Method

Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted with a calculated random sample of a population with 1.250 teachers distributed in all 37 elementary schools located in a large city in the metropolitan area of Porto Alegre (Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil). The parameters for sample size calculation were 50% prevalence, 5% error, 80% effect power and 20% potential losses. The final sample consisted of 713 teachers. The collected sample consisted of 679 teachers, with a loss of 34 participants.

Most participants were women (91.8%), with a partner (60.8%) and children (68.6%). Their average age was 42 years (SD±9) and their salaries were over three minimum wages, a reference in Brazil (51.2%). Most participants had a post-graduate degree (61.8%). The majority of the professionals worked exclusively at the school under investigation (74.2%). Participants had an average of 17 years of professional experience (range=1-47, SD±8.9, Mo=15) and 8.8 years of professional experience at the school (SD±7.2). The workload varied between 16 and 57 hours a week, with an average of 34 hours a week (SD±11.6, Mo=40). The amount of students they work with per day ranged between 7 and 500, with an average of 77 students per day (SD±74, Mo=60).

Measures

Data were collected through a questionnaire specifically designed to investigate some sociodemographic factors (gender, age, marital status, children) and work variables (education, weekly workload at the institution, wages, time working at the institution, work in other activities, jobs at other schools). Additionally, the following self-report instruments were used:

Spanish Burnout Inventory, Education professionals version (SBI-Ed), adapted to Brazil, by Gil-Monte, Carlotto and Câmara (2010), composed of 20 items divided into four subscales: enthusiasm toward the job (reversed) (5 items, alpha=.83; e.g., I see my job as a source of personal accomplishment); psychological exhaustion (4 items, alpha=.80; e.g., I feel emotionally exhausted); indolence (6 items, alpha=.80; e.g., I don’t like taking care of some students); and guilt (5 items, alpha=.82; e.g., I regret some of my behaviors at work). The items were answered on a 5-point frequency scale: 0 (Never) to 4 (Very frequently: every day). To assess the profiles, one can combine the scores on each subscale into a single score, as an average score. The Profile 1 score is estimated as the average of the 15 items from the subscales of enthusiasm toward the job (reversed), psychological exhaustion, and indolence. The Profile 2 score is estimated by the average of these 15 items together with the average of the guilt subscale.

Battery of Psychosocial Risk Assessment (Unidad de Investigación Psicosocial de la Conducta Organizacional – UNIPSICO) by Gil-Monte (2005), which assess: autonomy (5 items, alpha=.77; e.g., My job provides me possibilities to use my own initiative); conflict role (5 items, alpha=.76; e.g., I have to do things differently from what I think they should be done); ambiguity role (reversed) (5 items, alpha=.78; e.g., I know what my responsibilities at work are); overload (6 items, alpha=.79; e.g., I feel that I do not have enough time to finish my work); social support (5 items, alpha=.84; e.g., I count on the help of friends when I have problems at work); and negative feedback (6 items, alpha=.71; e.g., The organization informs me when my performance is poor); interpersonal conflicts (5 items, alpha=.76; e.g., I have been experiencing conflicts with students). All items were answered on a 5-point frequency scale: 0 (Never) to 4 (Very frequently: every day).

Procedures

First, the City’s Educational Department was contacted, to which the object of the study was presented in order to obtain authorization and support for the implementation of the instruments. Teachers answered the instruments at their workplace. The instruments were collected after being filled out. The application occurred from September to November 2013. The first author of this study collected the data. The participants were informed about the objective of the study, as well as its voluntary, anonymous and confidential character. Research ethics committees of [institution name omitted for review] approved the study.

The statistical software PASW, version 22 (SPSS/PASW, Inc., Chicago, IL), was applied for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate frequencies, average scores and standard deviations.

Burnout prevalence was assessed by means of the cutoff points of the SBI manual from the calculation of percentiles (P) (Gil-Monte, 2011). Scores ≥P90 were classified as high levels of the dimensions. For the Profile 1 it was considered the cases that presented scores ≥P90 in the average scoring of the 15 items of the subscales of enthusiasm toward the job (reversed), psychological exhaustion and indolence, and <P90 in the guilt subscale. The cases included in Profile 2 were those of participants with scores ≥P90 in the average scoring of the 15 items mentioned above, and ≥P90 in the guilt subscale as well.

Multiple linear regression analysis (Stepwise method) was performed, using as dependent variables each burnout dimension, and, the psychosocial risks as independent variables. The predictor variables were selected with a p<.05 level of significance. In the regression analysis, the power of the obtained significant effects, standardized regression coefficients – which can be considered as effect sizes in terms of standard deviation units – were calculated for each final model, according to Field (2009).

Results

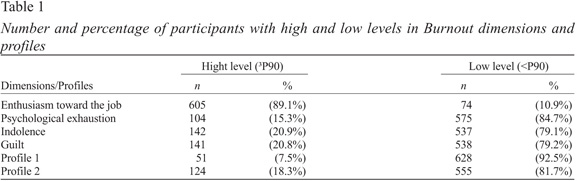

Results reveal a prevalence of 10.9% of participants with feelings of low enthusiasm for the job, 15.3% with high level of psychological exhaustion, 20.9% of indolence, and 20.8% of guilt. When considering the total scoring in the Spanish Burnout Inventory scale, composed of 15 items, the percentage of subjects that indicated high levels of Burnout, considering the criterion adopted, was 7.5%. In the Spanish Burnout Inventory scoring and guilt dimension, 18.3% presented high scores (Table 1).

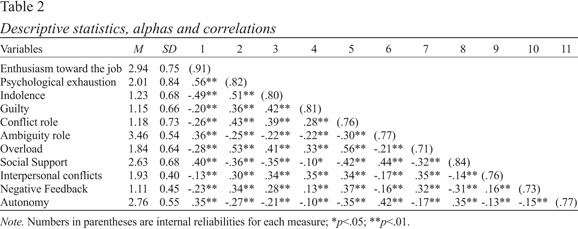

Table 2 displays the means, standard deviation, alpha values and correlation matrix between the study variables. The instruments reveal adequate rates of internal consistency, assessed by Cronbach’s α (Bland & Altman, 1997), ranging from .71 to .89. The variables present correlations ranging from weak (r=-.10) to moderate (r=.56).

Table 3 shows the results of multivariate regression analysis for the variables predicting the four burnout dimensions. The results for enthusiasm toward the job identified a predictor model composed of the variables social support, autonomy, overload, ambiguity role and negative feedback. This model explained 25.3% of the variance for this dimension. Thus, higher levels of social support (β=.206) and autonomy (β=.1813), predicted higher enthusiasm toward the job. Higher levels of overload (β=-.132), ambiguity role (β=.149) and negative feedback (β=-.075) predicted less enthusiasm toward the job.

Regarding psychological exhaustion, the final model was explained by the variables overload, negative feedback, interpersonal conflicts, social support and autonomy, with 37.1% of its total variability explained. Particularly, lower levels of social support (β=-.135) and autonomy (β=-.123) predicted depersonalization. Higher levels of psychological exhaustion increase as overload (β=.387), negative feedback (β=.138) and interpersonal conflicts increases (β=.113).

Indolence was predicted by the variables overload, interpersonal conflicts, negative feedback, conflict role and social support. This model explained 27.5% of the variance for this dimension. Higher levels of overload (β=.200), interpersonal conflicts (β=.193), and negative feedback (β=.086) and low levels of social support (β=-.187) predicted higher levels of indolence.

The results for guilt identified a predictor model composed of the variables social interpersonal conflict, overload, ambiguity role, and social support. This model explained 19.1% of the variance for this dimension. Thus, higher levels of interpersonal conflicts (β=.365), overload (β=.231) and ambiguity role (β=-.162) predicted higher indolence. Higher levels of social support (β=.085), predicted less indolence.

Note that, in this sample, overload and social support are variables with common predictive value in explaining the variability of Burnout in all four dimensions. Overall, results found are between the medium (R2=.123) and large effect sizes (R2=.371) as recommended by Field (2009).

Discussion

The analysis of the results regarding the prevalence of both Burnout profiles identified that 7.5% of the participants are classified into Profile 1, and 18.3% into Profile 2. The prevalence of Profile 1 proves inferior and Profile 2 superior to results obtained in a sample of Brazilian teachers from schools in Porto Alegre and metropolitan area (Gil-Monte, Carlotto, & Câmara, 2011), which identified 12% for Profile 1, and 5.6% for Profile 2. Unda (2010), in study with Mexican teachers, identified superior prevalence for Profile 1 (35%) and inferior for Profile 2 (17.2%). Similar result was found by Figueiredo-Ferraz, Gil-Monte and Grau-Alberola (2009), with Portuguese teachers, whose prevalence was superior in Profile 1 (14.2%) and inferior in Profile 2 (1.9%) as well.

From the cutoff points used, all 175 cases identified in this study could be classified as positive for BS, in accordance with both Brazilian legislation and the theoretical model adopted. It is important to highlight that, in addition to prevalence, Burnout presents levels depending on the frequency and intensity of symptoms (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). In this sense, the percentage of teachers in both profiles proposed by Gil-Monte (2005) theoretical model is worrisome, because, for being currently working, they may be aggravating the situation (Gil-Monte et al., 2011), increasing the chances of work leave (Ahola, Väänänen, Koskinen, & Shirom, 2010), besides being developing their activities poorly (Maslach & Goldberg, 1998), with damages to the student’s learning process (Carlotto, 2012; Gil-Monte et al., 2011).

It is worth alerting that, in all of the cases, a clinical interview and other psychological assessment methods need to be performed in order to confirm the diagnosis (Amazarray, Câmara, & Carlotto, 2014). Such measure is important to rule out other pathologies that may be influencing the assessed symptoms (Gil-Monte et al., 2011).

The analysis of the predictors of the dimension Enthusiasm toward the job validates studies that identified association between Burnout and social support (Brouwers et al., 2011; Ho, 2016), autonomy (Brouwers et al., 2011; Schwab & Iwanicki, 1982), ambiguity role (Papastylianou, Kaila, & Polychronopoulos, 2009), overload (Yong & Yue, 2007) and negative feedback (Elloy, Everett, & Flynn, 1991).

It is possible to think that, as teachers count with the support of coworkers, develop their activities with autonomy, which is an important characteristic for engagement with the job (Yong & Yue, 2007), act free from doubt about the activities they need to carry out, which are the competences of their role with an workload assessed as adequate, they manage to dimension their goals, to see them as attractive and to obtain better results and personal satisfaction (Gil-Monte, 2005).

The psychological exhaustion dimension was associated with overload, negative feedback and interpersonal conflicts, and to less social support and autonomy. Increased work demand with low autonomy, in an environment with conflictive relationships, boosts psychological exhaustion.

The context of intensification of the teaching profession contributes to immediacy and urgency, because crisis situations are the most recurrent ones in everyday living. On top of that, there is the time pressure resulting from administrative systems that push teachers into developing their job, without considering the actual time necessary for its execution. In an attempt to handle the complexity derived from constant educational reforms, the state hires resource-people to provide specialized services that cause some role confusion and may originate interpersonal conflicts (Maranda et al., 2014) and less social support (Kahn, Schneider, Jenkins-Henkelman, & Moyle, 2006).

Indolence had as predictors overload, interpersonal conflicts, negative feedback, role conflict and less social support. The overload routine, permeated by interpersonal stressors, leads the teacher to develop negative attitudes of indifference, insensitivity and detachment from students. Moreover, the teacher often receives messages to perform two or more conflicting roles, having to act contrarily to his or her conceptions of educative practice (Nwikina & Nwanekezi, 2010).

The teaching profession has as an important effectiveness indicator the positive feedback on a teacher’s performance that is primarily established through interpersonal relationships. In a context of conflicting relationships and little social support, there is the predominance of a negative program focused more on difficulties than on achievements.

Concerning the guilt dimension, it was observed that the greater the interpersonal conflicts, the overload, the role ambiguity and the social support deficiency, the stronger the feeling of guilt. There is a social expectation about a teacher’s attributions, which is interiorized by the subject. It is invariably linked to the concept of relationship. The guilt is a result of the perception of not being performing the expected role. Interpersonal conflicts configure a scenario of ineffectiveness that, connected with overload, prevents the actual dimensioning of the teacher’s skills, in addition to making the function to be carried out unclear. Social support emerges as a risk factor for guilt. It is possible that, as teachers do not count with appreciation and support from students, parents and the direction board, they do not think they are doing their job good enough, believing that their performance does not meet the expectations.

Results point predictor models of burnout dimensions composed of psychosocial risks derived from the type of the activity, and of interpersonal risks, with highlight to the variables social support and overload, which are present in all of the dimensions. This reveals the importance of balancing the activities according to the teacher’s workload, as well as of developing positive interpersonal relationships.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of the present study is that data among teachers was collected only in public schools, reducing possible biases associated with data collection in private schools that present differentiated conditions of work. Additionally, this study made use of a strong theoretical basis with reliable and valid instruments to collect data. The study contributes to the construction of a theoretical model based on the stressors identified in the literature, which are usually evaluated individually or with few stressors.

The sample size used was sufficient to provide power for a significant effect size in statistical analysis, as recommended by Cohen (1992).

The results of this study should be considered in light of some limitations, such as the cross-sectional design, which does not allow for conclusions in terms of causality. Another limitation of the study is the use of self-reported measures, which may increase the possibility of response bias. The third one is the healthy worker effect, a peculiar question in cross-sectional studies on occupational epidemiology that often exclude a possible ill subject (McMichael, 1976). This situation may underestimate the size of the identified risks, because the most affected individuals cannot keep their jobs, having to leave it temporarily for health treatment.

Therefore, further studies, of longitudinal design, should be conducted in order to assess the incidence of the syndrome and its causal factors. Studies with teachers from other regions and states and from other education realities are recommended to broaden the knowledge about Burnout among municipal school teachers.

Conclusion

Overall, this study contributes to the development of theoretical knowledge in the burnout area among teachers. Furthermore, the findings have important implications for the occupational psychology field, practitioners and school principals. Particularly, results should be used to shed light on possible applied interventions among teachers, such as the improvement of positive social support and the accomplishment of training programs aimed at developing interpersonal relationship skills. At the organizational level, interventions should consider factors related to overload and role conflict and ambiguity.

This study has several important implications for policymakers. In this sense, it is important that public managers and educators discuss a teacher’s role, seeking a realistic replanning in terms of workload and clarity in the attributions considering, in addition to work issues, the health of the whole school context.

References

Ahola, K., Väänänen, A., Koskinen, A., & Shirom, A. (2010). Burnout as a predictor of all-cause mortality among industrial employees: A 10-year prospective registerlinkage study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69, 51-57. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.002 [ Links ]

Amazarray, M. R., Câmara, S. G., & Carlotto, M. S. (2014). Investigação em saúde mental e trabalho no âmbito da saúde pública no Brasil. In A. R. C. Merlo, C. G. Bottega, & K. V. Perez (Eds.), Atenção à saúde mental do trabalhador: Sofrimento e transtornos psíquicos relacionados ao trabalho (pp. 75-92). Porto Alegre: Evangraf. [ Links ]

Bland, J., & Altman, D. (1997). Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. British Medical Journal, 314, 570-572.

Brouwers, A., Tomic, A., & Boluijt, H. (2011). Job demands, job control, social support and self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of burnout among physical education teachers. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 7, 17-39. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v7i1.103

Carlotto, M. S. (2012). Síndrome de Burnout em professores: Avaliação, fatores associados e intervenção. Porto, Portugal: LivPsic. [ Links ]

Carlotto, M. S., & Câmara, S. G. (2008). Análise da produção científica sobre a síndrome de Burnout no Brasil. PSICO, 39, 152-158. [ Links ]

Carlotto, M. S., Dias, S. R. S., Batista, J. B. V., & Diehl, L. (2015). O papel mediador da autoeficácia na relação entre a sobrecarga de trabalho e as dimensões de Burnout em professores. Psico-USF, 20, 13-23. Recuperado de http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712015200102 [ Links ]

Cebrià-Andreu, J. (2005). El síndrome de desgaste profesional como problema de salud pública. Gaceta Sanitária, 19, 470-470. Recuperado de http://dx.doi.org/10.1157/13082793 [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155-159. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [ Links ]

Costa, F. R. C. P., & Rocha, R. (2013). Fatores estressores no contexto de trabalho docente. Revista Ciências Humanas, 6, 18-43. [ Links ]

Diehl, L., & Carlotto, M. S. (2014). Knowledge of teachers about the burnout syndrome: Process, risk factors and consequences. Psicologia em Estudo, 19, 741-752. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-73722455415 [ Links ]

Elloy, D., Everett, J. E., & Flynn, W. R. (1991). An examination of the correlates of job involvement. Group and Organization Studies, 16, 160-177. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/105960119101600204 [ Links ]

Farber, B. A. (1991). Crisis in education. Stress and burnout in the American teacher. São Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc. [ Links ]

Fernandes, M. H., & Rocha, V. M. (2009). Impact of the psychosocial aspects of work on the quality of life of teachers. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 31, 15-20. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462009000100005 [ Links ]

Field, A. P. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. London: Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]

Figueiredo-Ferraz, H., Gil-Monte, P. R., & Grau-Alberola, E. (2009). Prevalencia del síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo (burnout) en una muestra de maestros portugueses. Aletheia, 29, 6-15. [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R. (2005). El síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo (burnout): Una enfermidad laboral en la sociedad del bienestar. Madrid: Pirâmide. [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R. (2008). El síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo (burnout) como fenómeno transcultural. Informació Psicológica, 91-92, 4-11. [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R. (2011). CESQT: Cuestionario para la evaluación del síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo. Madrid: TEA. [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R. (2012). The influence of guilt on the relationship between burnout and de-pression. European Psychologist, 17, 231-236. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000096 [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R., Carlotto, M. S., & Câmara, S. (2010). Validation of the Brazilian version of the “Spanish Burnout Inventory” in teachers. Revista de Saúde Pública, 44, 140-147. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102010000100015

Gil-Monte, P. R., Carlotto, M. S., & Câmara, S. G. (2011). Prevalência de burnout em uma amostra de professores brasileiros. European Journal of Psychiatry, 25, 205-212. [ Links ]

Guglielmi, R. S., & Tatrow, K. (1998). Occupational stress, burnout, and health in teachers: A methodological and theoretical analysis. Review of Educational Research, 68, 61-69. [ Links ]

Guidetti, G., Viotti, S., Gil-Monte, P. R., & Converso, D. (2017). Feeling guilty or not guilty. Identifying burnout profiles among Italian Teachers. Current Psychology, 1-12. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9556-6 [ Links ]

Ho, S. K. (2016). Relationships among humour, self-esteem, and social support to burnout in school teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 19, 41-59. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9309-7 [ Links ]

Jani, B. (2017). Stress of teachers working at primary school in Kalahandi. International Education & Research Journal, 3, 71-74. [ Links ]

Kahn, J. H., Schneider, K. T., Jenkins-Henkelman, T. M., & Moyle, L. L. (2006). Emotional social support and job burnout among high-school teachers: is it all due to dispositional affectivity?. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 793-807. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/job.397 [ Links ]

Khosla, M. (2013). Gender, locale and type of institution as determinents of professional burnout among elementary school teachers. Edubeam Multidisciplinary Online Research Journal, X, 1-18. [ Links ]

Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2008). Engagement and emotional exhaustion in teachers: Does the school context make a difference? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57(Suppl.), 127-151. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00358.x [ Links ]

Konukman, F., Agbuğa, B., Erdoğan, Ş., Zorba, E., Demirhan, G., & Yılmaz, I. (2010). Teacher-coach role conflict in school-based physical education in USA: A literature review and suggestions for the future. Biomedical Human Kinetics, 2, 19-24. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/v10101-010-0005-y [ Links ]

Kroupis, I., Kourtessis, Th., Kouli, O., Tzetzis, G., Derri, V., & Mavrommatis, G. (2017). Job satisfaction and burnout among Greek P.E. teachers: A comparison of educational sectors, level and gender. CCD. Cultura_Ciencia_Deporte, 12(34), 5-14. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.12800/ccd.v12i34.827 [ Links ]

Leiter, M. P., Bakker, A. B., & Maslach, C. (2014). Burnout at work. New York: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

López, J. M. O., Bolaño, C. C., Mariño, M. J. S., & Pol, E. V. E. (2010). Exploring stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction in secondary school teachers. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 10, 107-123. [ Links ]

Manzano-Garcia, G., & Ayala-Calvo, J. C. (2013). New perspectives: Towards an integration of the concept “burnout” and its explanatory models. Anales de Psicología, 29, 800-809. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.145241

Maranda, M.-F., Viviers, S., & Deslauriers, J.-S. (2014). “Escola em sofrimento”: Pesquisa-ação sobre situações de trabalho de risco para a saúde mental em meio escolar. Cadernos de Psicologia Social do Trabalho, 17, 141-152. doi: 10.11606/issn.1981-0490.v17ispe1p141-151

Maslach, C., & Goldberg, J. (1998). Prevention of burnout: News perspectives. Applied & Preventive Psychology, 7, 63-74. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80022-X [ Links ]

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2, 99-113. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205 [ Links ]

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 498-512. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498 [ Links ]

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review Psychology, 52, 397-422. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 [ Links ]

Masmoudi, R., Trigui, D., Ellouze, S., Sellami, R., Baati, I., Feki, I., & Masmoudi, J. (2016). Burnout and associated factors among Tunisian teachers. European Psychiatry, 33, 796-797. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.01.2393 [ Links ]

McCarthy, C. J., Lambert, R. G., O’Donnell, M., & Melendres, L. T. (2009). The relation of elementary teachers’ experience, stress, and coping resources to burnout symptoms. The Elementary School Journal, 109, 282-300.

McMichael, A. J. (1976). Standardized mortality ratios and the “healthy worker effect”: Scratching beneath the surface. Journal of Occupational Medicine, 18, 165-168. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00043764-197603000-00009

Mearns, J., & Cain, J. E. (2003). Relationships between teachers’ occupational stress and their burnout and distress: Roles of coping and negative mood regulation expectancies. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 16, 71-82. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1061580021000057040

Mercado-Salgado, P., & Gil-Monte, P. R. (2010). Influencia del compromiso organizacional en la relación entre conflictos interpersonales y el síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo (burnout) en profesionales de servicios (salud y educación). Innovar Revista de Ciencias Administrativas y Sociales, 20(38), 161-174. [ Links ]

Nwikina, L., & Nwanekezi, A. (2010). Management of job-related teacher burnout in Nigerian schools. Academia Arena, 2. Retrieved from http://sciencepub.net/academia/aa0207/06_3535aa0207_31_38.pdf [ Links ]

Olivier, M., & Williams, E. (2005). Teaching the mentally handicapped child: Challenges teachers are facing. The International Journal of Special Education, 20, 19-31. [ Links ]

Papastylianou, A., Kaila, M., & Polychronopoulos, M. (2009). Teachers’ burnout, depression, role ambiguity and conflict. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 12, 295-314. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11218-008-9086-7

Prilleltensky, I., Neff, M., & Bessell, A. (2016). Teacher stress: What it is, why it’s important, how it can be alleviated. Theory Into Practice, 55, 104-111. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1148986

Rabasa, B., Figueiredo-Ferraz, H., Gil-Monte, P. R., & Llorca-Pellicer, M. (2016). The role of guilt in the relationship between teacher’s job burnout syndrome and the inclination toward absenteeism. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 21, 103-119. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/0.1387/RevPsicodidact.13076

Schwab, R. L., & Iwanicki, E. F. (1982). Who are our burned out teachers?. Educational Research Quaterly, 7(2), 5-16. [ Links ]

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017). Still motivated to teach? A study of school context variables, stress and job satisfaction among teachers in senior high school. Social Psychology of Education, 20, 15-37. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9363-9 [ Links ]

Smetackovaa, I. (2017). Self-efficacy and burnout syndrome among teachers. The European Journal of Social and Behavioural Sciences EJSBS, XX. Retrieved from https://www.futureacademy.org.uk/files/images/upload/ejsbs219.pdf [ Links ]

Stoeber, J., & Rennert, D. (2008). Perfectionism in school teachers: Relations with stress appraisals, coping styles, and burnout. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 21, 37-53. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701742461 [ Links ]

Unda, S. (2010). Estudio de prevalencia del Síndrome de Quemarse por el Trabajo (SQT) y su asociación con sobrecarga y autoeficacia en maestros de primaria de la ciudad de México. Ciencia & Trabajo, 12(35), 257-262. [ Links ]

World Health Organization [WHO]. (2001). The World Health Report 2001. Mental health: New understanding, new hope. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/whr/2001/en/ [ Links ]

Yong, Z., & Yue, Y. (2007). Causes for burnout among secondary and elementary school teachers and preventive strategies. Chinese Education and Society, 40(5), 78-85. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932400508 [ Links ]

Zhou, Y., & Wen, J. X. (2007). The burnout phenomenon of teachers under various conflicts. Education Review, 4, 37-44. [ Links ]

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Mary Sandra Carlotto, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos – UNISINOS, Av. Unisinos, 950, Cristo Rei, São Leopoldo, RS, 93020-190, Brasil. E-mail: mscarlotto@gmail.com

This work was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Brazil [grant numbers 443146/2015-2].

Submitted: 26/08/2017 Accepted: 13/11/2018