Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Psicológica

versão impressa ISSN 0870-8231versão On-line ISSN 1646-6020

Aná. Psicológica vol.37 no.3 Lisboa jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1525

Perceptions of Portuguese psychologists about the acceptability of a child intervention targeted at inhibited preschoolers

Perceções dos psicólogos portugueses acerca da aceitabilidade de uma intervenção dirigida a crianças inibidas em idade pré-escolar

Maryse Guedes1, Stephanie Alves1, António J. Santos1, Manuela Veríssimo1, Andrea Chronis-Tuscano2, Christina Danko2, Kenneth H. Rubin3

1William James Centre for Research, ISPA – Instituto Universitário, Lisboa, Portugal

2Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park, USA

3Department of Human Development & Quantitative Methodology, University of Maryland, College Park, USA

ABSTRACT

High and stable behavioral inhibition (BI) during early childhood have been associated with an increased risk of later anxiety disorders and peer difficulties. Developing evidence-based early interventions to prevent these unhealthy developmental trajectories has become a major focus of interest. However, these interventions are not yet available in Europe. This study aimed to explore the perceptions of Portuguese psychologists about the acceptability of the child component of the Turtle Program, before its dissemination in Portugal. Eighteen psychologists were distributed into three focus groups. Each group was moderated by a trained psychologist, using a semi-structured interview guide. The thematic analysis revealed that Portuguese psychologists acknowledged that the intervention needs to go beyond social skills training and enhance children’s positive self-perceptions. Overall, psychologists perceived the structure, contents, activities, and materials of the intervention to be acceptable. However, participants recommended minor modifications to strengthen the connection with naturalistic contexts, broaden the focus on emotional expressiveness and social interaction, and introduce creative activities and materials. These findings are consistent with previous research with LatinX practitioners, who typically agree with the acceptability of evidence-based child intervention principles and only report the need to introduce minor changes related to the way how interventions are delivered to children.

Key words: Behavioral inhibition, Preschool years, Social skills facilitated play, Treatment acceptability.

RESUMO

Níveis elevados e estáveis de inibição comportamental em idade pré-escolar associam-se a um risco acrescido de desenvolver perturbações de ansiedade e dificuldades com os pares. O desenvolvimento de intervenções baseadas na evidência para prevenir estas trajetórias inadaptativas têm merecido um interesse crescente. Todavia, estas intervenções ainda não se encontram disponíveis na Europa. Este estudo teve como objetivo explorar as perceções de aceitabilidade dos psicólogos portugueses acerca do componente para crianças do Turtle Program, antes da sua disseminação em Portugal. Dezoito psicólogos foram distribuídos em três grupos focais. Cada grupo foi moderado por um investigador treinado, com base num guião semiestruturado. A análise temática revelou que os psicólogos portugueses reconheceram a necessidade de ultrapassar o enfoque no treino de competências sociais e de promover auto-perceções positivas nas crianças. Globalmente, os psicólogos percecionaram a estrutura, os conteúdos, as atividades e os materiais de intervenção como aceitáveis. Todavia, os participantes recomendaram modificações menores ao nível da articulação com o contexto pré-escolar, do foco na expressão emocional e interação social, da introdução de atividades e materiais criativos. Estes resultados são consistentes com a investigação existente com profissionais oriundos de culturas latinas que apenas sugerem adaptações na forma como as intervenções são apresentadas às crianças.

Palavras-chave: Inibição comportamental, Idade pré-escolar, Jogo supervisionado de promoção de competências sociais, Aceitabilidade da intervenção.

Defined as a biologically-based wariness when exposed to novel people, situations and objects (Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, 2005), behavioral inhibition (BI) has been identified as a key antecedent of anxious withdrawal (AW) in the presence of unfamiliar and familiar peers at preschool (Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009). High and stable BI/AW during the preschool years have been associated with a variety of negative socioemotional consequences, namely with an increased risk of experiencing later anxiety disorders (especially, social anxiety), peer victimization and exclusion (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Rubin, Bowker, Barstead, & Coplan, 2018).

Rubin’s developmental and transactional model establishes that high BI/AW can prevent children from developing age-appropriate social, socio-cognitive and interpersonal negotiating skills (Rubin et al., 2009). The recognition of low social and socio-cognitive skills may evoke negative peer responses and lead to the development of negative social self-perceptions (Rubin et al., 2018) that contribute to the maintenance of BI/AW and increase the risk of later negative socioemotional outcomes (Rubin et al., 2009). In addition, research has shown that inhibited children who display low emotion-regulation skills are at increased risk of later social maladjustment (Smith, Hastings, Henderson, & Rubin, 2019). The unhealthy developmental pathways associated with high and stable BI/AW can be prevented, if child’s social, socio-cognitive and emotion-regulation skills are promoted during early childhood (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2018).

Based on the knowledge of these transactional influences, there has been an increasing interest in multi-modal evidenced-based interventions targeted at BI/AW during early childhood, like the Turtle Program, which has been recently developed in the USA (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015).

The child component of the Turtle Program

The Turtle Program consists of eight group sessions of 90 minutes weekly, with five-six families (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015). Contrary to previously available evidence-based interventions (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2018), the Turtle Program includes not only a parent component based on the principles of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008) adapted to anxiety problems (Pincus, Eyberg, & Choate, 2005), but also a child component aimed at teaching and practicing social and emotion-regulation skills (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015). The child sessions are an extension of the Social Skills Facilitated Play Program, which combines the benefits of systematic modelling, in-vivo coaching and reinforcement of social skills in a peer group context with those of specific training on social, social problem-solving, emotion-regulation and relaxation strategies (Coplan, Schneider, Matheson, & Graham, 2010).

The child component of the Turtle Program is fully described elsewhere (Danko, O’Brien, Rubin, & Chronis-Tuscano, 2018). The general structure of each session is similar, with the exception of the last session that includes a final graduation party with parents, in which children receive a bravery certificate. After child’s arrival (10 minutes), each session begins with 10-15 minutes of non-facilitated free play, in which the group leaders observe children’s social and non-social activities and do not directly interact with them. During the brief, didactic circle time (10 minutes), group leaders begin with a familiar and non-threatening activity (e.g., preschool calendar, introductions) and, then, teach, model and practice a specific social, problem-solving or emotion-regulation skill, using puppets and storytelling in consideration of the children’s developmental level. The skills focused on the didactic circle time during the eight sessions are, as follows: (1) introducing oneself; (2) making eye contact; (3) communicating to keep friends; (4) facing fears; (5) expressing positive and negative emotions; (6) dealing with disappointment, when a peer refuses to play; (7) working together; and (8) review of the learned skills. Thereafter the circle time, children are involved in facilitated free play (10-15 minutes) in which group leaders systematically reinforce specific social skills (combining labeled praises and stickers) and promote social problem-solving. During snack time (10 minutes), group leaders should let the children take the lead of the conversation, model pleasant social interaction and introduce games (e.g., share personal interests) that may promote social interaction, if children are not initiating conversation spontaneously. Then, children are again involved in facilitated free play. The session ends with a structured group activity (5 minutes) that promotes collaborative play (e.g., parachute or duck, duck, goose) or the exposure to feared situations (show and tell) during which children are praised for social-approach behaviors. Mid-session activities take place during certain sessions, such as book read (session 1), balloon breathing (session 2), or scavenger hunt (sessions 7 and 8) to practice the gradual exposure to social situations with unfamiliar adults. All the intervention sessions take place in a playroom, which is equipped with play materials that can be used in a solitary, dyadic or group way to encourage dramatic (e.g., puppets, play food,), constructive (e.g., Legos), and competitive play (e.g., basket-ball). At the end of each session, parents are given a handout with a brief summary of the session content and child’s main achievements.

A pilot randomized controlled trial has shown that US families assigned to the Turtle Program displayed significant improvements on child BI, social anxiety symptoms (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015), and social interactions observed in preschool classrooms (Barstead et al., 2018) when compared with families assigned to a waiting-list control condition. The Social Skills Facilitated Play Program, which has been extended in the child component of the Turtle Program, has also shown promising results in Canada (Coplan et al., 2010), Australia (Lau, Rapee, & Coplan, 2017) and China (Li et al., 2016). However, these child interventions are not yet available in European countries, like Portugal, where the prevalence rates of anxiety disorders are high (Caldas-Almeida & Xavier, 2013) and concerns about peer victimization are increasing (Comissão Nacional de Promoção dos Direitos e Proteção de Crianças e Jovens, 2018).

The influence of culture on peer attitudes and responses toward BI/SW

Within an ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), cultural values, beliefs and practices influence how peers perceive, evaluate and respond to social behaviors (Chen & French, 2008), such as BI/AW. In Western individualistic cultures with a greater emphasis on autonomy, sociability and assertiveness, social initiative is more likely to be viewed as an index of social maturity and accomplishment than in Eastern and LatinX cultures valuing group harmony and cohesiveness (Chen, French, & Schneider, 2006). Cross-cultural studies have shown that inhibited/withdrawn children from cultures with a greater emphasis on social initiative (e.g., Italy, USA, Canada) are less likely to be accepted and to experience positive responses from peers when initiating social interactions than inhibited/withdrawn children from cultures (e.g., China) valuing group harmony and cohesiveness (Atilli, Vermigli, & Schneider, 1997; Chen et al., 2004).

In Portugal, the LatinX tradition increasingly coexist with individualistic values (Wall & Gouveia, 2014). Recent Portuguese empirical studies (Santos et al., 2015) and US-Portugal comparisons (Vaughn et al., 2016) have shown that preschoolers who displayed low social engagement were less visible for peers and less likely to be chosen as preferred playmates by peers. Associations between AW and sociometric measures of negative peer outcomes have been also observed among Portuguese adolescents (Correia, Santos, Freitas, Ribeiro, & Rubin, 2014). However, prosocial behaviors have appeared to play an especially relevant protective role against the negative peer outcomes that have been typically associated with AW (Freitas, Santos, Ribeiro, Daniel, & Rubin, 2019), reflecting possibly the salience of values related to solidarity, equality and support to others in Portugal (European Commission, 2012). Thus, the coexistence of collectivist and individualistic values in Portugal may impact, in a specific way, on peer attitudes and responses toward BI/AW.

Culture and treatment acceptability of evidence-based child interventions targeted at anxious children

Due to these cultural influences, the dissemination of evidence-based intervention programs in new contexts needs to be based on a prior assessment of treatment acceptability (Barrera, Castro, Strycher, & Tooberg, 2013), that is, of the extent to which intervention procedures are perceived as socially appropriate (Wolf, 1978), fair and reasonable (Kazdin, 1980). Within comprehensive frameworks of treatment acceptability (Carter, 2008; Lennox & Miltenberger, 1999), the perspectives of practitioners working with the targeted groups needs to be taken into account. In fact, these perspectives can influence treatment implementation and recommendation and, consequently, treatment integrity and effectiveness (Chase & Peacock, 2017; Reimers, Wacker, & Koeppl, 1987).

Despite their relevance, the perspectives of practitioners about the acceptability of evidence-based child interventions targeted at BI/AW during early childhood remains relatively unknown. Most evidence has been derived from the clinical descriptions of practitioners working individually with LatinX school-aged children living in the USA, who were at higher risk of displaying or already displayed anxiety problems (Pina, Holly, Zerr, & River, 2014; Pina, Villalta, & Zerr, 2009). Globally, the principles and objectives of psychoeducation, social-emotional learning, relaxation and cognitive-behavioral exposure were perceived as consonant with the LatinX values and expectations (Pina et al., 2009). However, LatinX practitioners acknowledged the need to tailor the intervention to child’s individual needs, using culturally relevant contents and strategies (Pina, Polo, & Huey, 2019) to package and deliver the interventions (Pina et al., 2009). Suggested modifications included: (1) enhancing the involvement of the family in the intervention goals, activities and home practice; (2) adding more intervention sessions; (3) removing language associated with mental illness and normalizing the presented problems; (4) using facilitative family-oriented strategies to enhance the engagement of children in home experiences; and (5) introducing cultural enrichments focused on relevant sayings, metaphors and daily examples (Pina et al., 2009, 2014).

The perspectives of practitioners implementing the FRIENDS group anxiety intervention program targeted at school-aged children also appeared to support that the previously described intervention principles, their related contents (i.e., social, emotional and problem-solving skills, self-reward, support network identification) and activities (i.e., play-oriented techniques, like puppets, story books and colouring activities) were transculturally relevant (Barrett, Cooper, & Guarjado, 2014). This seemed to be also the case in Portugal, where practitioners also reported a high involvement of highly anxious children in the intervention activities (Pereira, Marques, Russo, Barros, & Barrett, 2014). However, practitioners implementing the FRIENDS programs recognized that culturally-sensitive modifications may be needed, namely in: (1) the contents related to self-esteem and establishing eye contact to be brave; (2) the involvement of family in the intervention; and (3) the use of culturally-relevant examples, creative activities and materials (Barrett et al., 2014; Sonderegger & Barrett, 2004).

To the best of our knowledge, the perceptions of practitioners about the acceptability of evidence-based child interventions targeted at inhibited preschoolers, like the child component of the Turtle Program, have not been previously explored in Southern European countries, in general, and in Portugal, in particular. Prior research has focused only on the perceptions of Portuguese practitioners about the acceptability of the parent component of the Turtle Program (Guedes et al., 2019). This focus groups study has found that Portuguese practitioners perceived the intervention objectives and contents as highly acceptable (except time-out) and recommended only minor changes in the way how intervention activities and materials are presented to parents. Similar qualitative studies are needed about the acceptability of the child component of the Turtle Program (Guedes et al., 2019) to shed light on practitioners’ views toward the original intervention procedures and materials prior to their dissemination (Mejia, Calam, & Sanders, 2015) and guide intervention development (Krueger & Casey, 2014) in new cultural contexts, like Portugal. Thus, the aim of the present study was to describe the perceptions of Portuguese psychologists about the acceptability of the objectives, format, structure, contents, activities, and materials of the child component of the Turtle Program.

Method

Participants

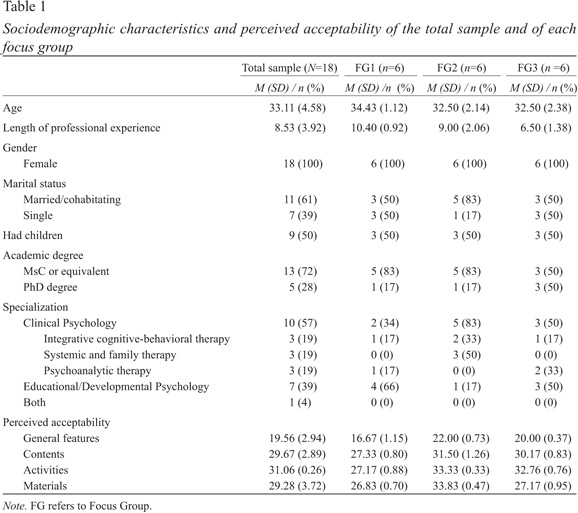

The sample consisted of 18 psychologists. For inclusion criteria, psychologists were required to be specialized in Clinical or Educational/Developmental Psychology, have experience in working with children, and be able to speak and understand Portuguese. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. All participants were female and most of them held an MsC or equivalent (i.e., had five years of college education) and were specialized in Clinical Psychology.

Three groups, composed of six participants each, were constituted. Each group was constituted considering: (1) the availability of the participants to attend the discussion; (2) the length of their professional experience to minimize the possibility that less experienced participants felt intimidated of exposing their perspectives in front of more experienced participants; and (3) the proportion of participants who worked together, to control the influence of the familiarity between participants and ensure group heterogeneity.

Instruments

Sociodemographic Questionnaire: This questionnaire collected information about the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Semi-Structured Interview Guide: The interview guide was structured, following the recommendations of Krueger and Casey (2014). After introducing focus groups objectives and procedures, participants were asked to introduce themselves and to define how they understood BI/AW during early childhood (introductory question). Then, participants were questioned about the kind of interventions that can be helpful for inhibited young children (transition question), before being invited to respond to key questions aimed at evaluating the acceptability of the child component of the Turtle Program. Based on a written booklet that provided a brief summary about the intervention and its targeted group, participants began to discuss their first impressions about the objectives, format and structure of the child component of the Turtle Program and appraised its contents, activities and materials. At the end of the discussion, participants were asked to summarize what they felt were the strengths of the intervention and the anticipated difficulties in its implementation in Portugal, and were given the opportunity to make final comments.

Perceived Acceptability Questionnaire: A 25-items questionnaire was developed to assess the perceived acceptability of Portuguese psychologists about the child component of the Turtle Program, based on four dimensions: General Features (e.g., objectives, format, structure; 5 items), Contents (7 items), Activities (7 items), and Materials (7 items). Participants were asked to answer each of the presented statements, using a Likert scale ranging from 1 – Not Adequate at All to 5 – Extremely Adequate. Higher mean values in each dimension indicate a higher perceived acceptability. Cronbach’s alfas ranged from .64 (Contents) to .79 (General Features).

Procedures

This study is part of a larger research project, approved by the [Guedes et al., 2019] Ethics Committee. Psychologists from the contact networks of the research group who met the inclusion criteria were initially contacted and informed about the study objectives and procedures. Psychologists who agreed to participate signed an informed consent and completed a sociodemographic questionnaire. The focus groups were scheduled, in accordance with the availability of the participants.

Each focus group lasted approximately two hours and was conducted by a trained moderator, in a quiet and comfortable location to ensure confidentiality. After reviewing the study objectives and procedures, the moderator ensured that all the participants agreed to allow the group discussion to be audio recorded. Then, the moderator conducted the discussion, using the semi-structured interview guide. At the end of the discussion, participants were asked to complete a self-report questionnaire to assess their perceptions of acceptability about the intervention program for triangulation purposes.

Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis was based on a continuous process of data collection, reduction, display and verification (Huberman & Miles, 1994). Each focus group was transcribed verbatim. Fictional names were used for confidentiality purposes. Data were analyzed, using QSR NVivo Pro 12. Following an existentialist/realistic epistemological approach, a deductive thematic analysis was conducted to identify, analyze and report patterns (themes) within data (Braun &

Results

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of the perceived acceptability of the general features, contents, activities and materials of the child component of the Turtle Program in each focus group. Globally, Focus Group 1 (FG1) perceived the general features, contents, activities and materials of the child component of the Turtle Program as moderately to highly adequate, whereas Focus Group 2 (FG2) and Focus Group 3 (FG3) globally perceived them as highly to extremely adequate.

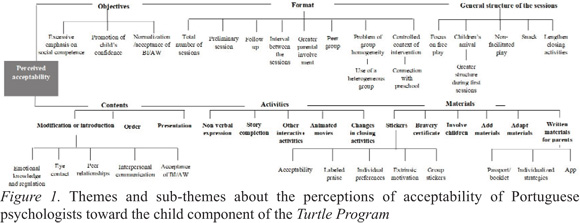

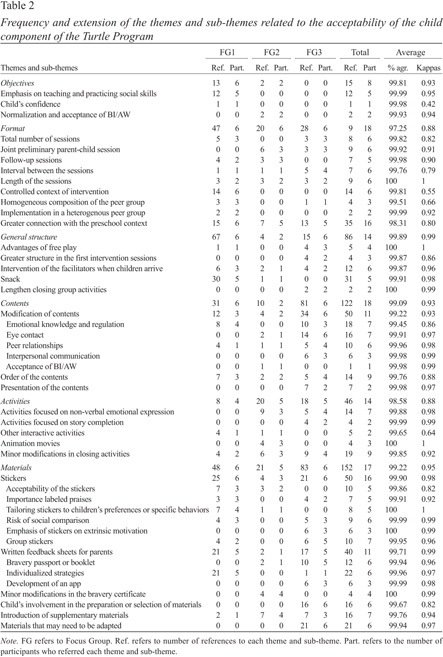

Figure 1 summarizes the themes and sub-themes that emerged from the thematic deductive analysis.

Objectives

The three focus groups perceived the intervention objectives as globally acceptable. However, Table 2 shows that most participants from FG1 discussed the main focus on teaching and practicing social skills, because inhibited preschoolers often hold appropriate social skills, but can be afraid to use them in social situations. FG1 suggested that the intervention may promote more directly child’s self-confidence, whereas FG2 recommended an objective focused on the normalization and acceptance of BI/AW. Isabelle explained:

“The advantage of a group format is the promotion of a sense of support. This can be very important for inhibited children (...). If children understand that there are other children with the same difficulties, this can be helpful to normalize these difficulties. This could be also the objective of the intervention: enhance the awareness that it is not so bad to be more inhibited.”

Format

Although FG1 was unsure about the adequacy of the total number of sessions, FG3 recommended a greater number of sessions to consolidate the learned skills and promote their generalization to naturalistic contexts. In particular, FG2 and FG3 discussed the introduction of a joint preliminary parent-child session, so that children can become familiar with the playroom, the facilitators and the peers. FG2 was more specific and suggested possible formats for a preliminary session, such as: an individual session with each family; a welcoming party; or a storytelling to prepare children for the transition to a novel situation.

Furthermore, FG1 and FG2 discussed the introduction of follow-up sessions to monitor the practice and generalization of the learned skills. Alternatively, some participants from FG2 and FG3 suggested a greater time interval (bi-weekly) between the sessions to give more time to families to practice the learned skills in naturalistic contexts. However, other participants from FG1 and FG3 agreed that weekly sessions would be a more appropriate time interval for preschool children.

Some participants from FG2 and FG3 were concerned about the length of the sessions, especially at the beginning of the intervention program. Heather explained:

“It would be important to start with shorter sessions and to gradually lengthen them over the eight weeks (...) Because it is possible that inhibited children don’t adhere to free play activities at the beginning of the intervention program.”

Conversely, other participants from FG1 and FG3 argued that the predominance of free play activities would ensure the adequacy of the length of the sessions.

The controlled context of the intervention and the homogeneous composition of the peer group were a major focus in FG1. Participants anticipated that the practice of social skills in a clinical setting with a group of inhibited peers may not prepare children for social interactions at preschool. To overcome anticipated difficulties, FG1 recommended the implementation of the intervention in a clinical setting with a heterogeneous peer group (i.e., inhibited and non-inhibited children). Alternatively, all groups recommended a greater connection with the preschool context to ensure that children continue to practice the learned skills in naturalistic contexts. Claire explained:

“During the preschool years, we know that the learning experiences take place in naturalistic contexts. This doesn’t invalidate the importance of the intervention program to promote learning experiences in a secure context (...) But if there is a continuity between the intervention program and the daily interactions with the child, the probability of success is substantially higher.”

More specifically, FG1 and FG2 recommended to implement later and follow-up sessions at preschool or to develop an intervention component targeted at preschool teachers. If not possible, all groups suggested alternative formats, such as: sharing interactive materials or activities with preschool teachers; organizing workshops and regular meetings with preschool teachers to enhance the reinforcement of the learned skills; or involving preschool teachers in the practice of home experiences.

General structure

The focus on the advantages of free play for the intervention with preschool children was a major topic of discussion in FG3. However, FG3 acknowledged that alternative activities with a greater structure may be needed during the first sessions, if inhibited children did not adhere to free play. All groups also discussed the intervention of the facilitators when children arrive. In particular, participants anticipated that the facilitators may need to guide the exploration behaviors of inhibited children during the first sessions and, then, to gradually promote child’s autonomy. Charlotte stated:

“When children arrive, exploring the playroom autonomously can be a blocking mechanism for inhibited children – it is an unfamiliar situation, with unfamiliar adults and peers. I would recommend to adapt the intervention of the facilitators when children arrive during the first weeks (...) Developing a trustful relationship with children is an important task. Without it, we will not be able to practice anything with children.”

The snack was a major focus of discussion in FG1. Due to the cultural relevance of meals, some participants from FG1 agreed that snack time is a natural and important opportunity to model and promote social interactions. However, other participants suggested a greater focus on non-verbal skills (e.g., observing or sharing) to model the balance between social conversation and silence during mealtimes. FG2 acknowledged that moving snack time to the end of the session can contribute to promote a more continuous involvement of children in free play activities.

FG3 recommended to lengthen the closing group activities (such as parachute or duck-duck-goose), because these activities are typically appreciated by children and may allow them to relax, after the exposure to challenging social interactions.

Contents

With respect to the modification of intervention contents, FG1 and FG3 suggested a greater focus on emotional knowledge and regulation. FG1 recommended a greater emphasis on the protective function of fear, on its manifestations in social contexts and on alternative emotion-regulation strategies (instead of balloon breathing) that can be more tailored to the needs of Portuguese children. Beyond the identification of facial expressions, FG3 suggested a greater emphasis on the behavioral cues related to different emotions, on individual differences in emotional expression and on more advanced tasks related to emotion recognition and understanding. Relatedly, FG2 emphasized the promotion of child’s acceptance toward BI/AW to strengthen child’s self-confidence.

Establishing eye contact was a major topic of discussion in FG3. Participants agreed that eye contact can be invasive and anticipated that the explanation provided during circle time (i.e., people might think that you are unfriendly or don’t like them if you don’t look at them) can be blaming for children. To overcome anticipated difficulties, some participants considered that eye contact can be naturally practiced during free play, instead of being focused on a single session. Alternatively, other participants recommended to normalize the discomfort related to eye contact during circle time and to gradually practice it. Sabrina explained:

“I think it will be useful to normalize the discomfort related to eye contact – when we don’t know people very well, it is normal that we feel it is difficult to look at them and eye contact is more difficult for some people than others. The importance of eye contact needs to be explained: it is more evident that we are interested in what people are saying when we look at them (...) And it can be helpful to give children alternative strategies, like establishing intermittent eye contact or looking at one point of other’s face instead of looking directly to his/her eyes.”

All groups recommended a greater focus on peer relationships. FG3 discussed the introduction of contents related to peers, group pressure and peer exclusion to discuss daily negative peer situations, explore how children felt and how these situations can be solved in an alternative way. FG1 and FG2 suggested to normalize the changeability of play preferences during the sixth session (e.g., playing alone, with peers or adults) and to provide psychoeducation on the concept of friendship during the third session.

Interpersonal communication was a major topic of discussion in FG3. Participants suggested focusing on active hearing (e.g., showing interest, or asking questions) to enhance the communication with friends and on assertiveness to deal with negative peer reactions in naturalistic contexts. Sabrina explained:

“A structured session on assertiveness can be important, because inhibited children may have experienced negative social interactions and may become aware that they are not alone, that others have some similar situations and understand what they are able to do in these situations (...) It is important to focus on challenging social situations that happen in naturalistic contexts.”

With respect to the order of the intervention contents, FG2 and FG3 considered that the introduction of the concept of friendship in the third session can be premature. FG1 recommended a first session focused on emotional expression and regulation (with a particular emphasis on social anxiety) and considered that establishing eye contact and showing interest (session 2) precedes asking to play (session 1) in the hierarchy of social fears. However, FG2 and FG3 anticipated that eye contact would be too invasive for the second session.

With respect to the presentation of the intervention contents, FG3 anticipated that some explanations about peer reactions to child’s behaviors may need to be reviewed (e.g., sharing emotions or dealing with peer rejection) to prepare children for challenging social interactions and enhance their cognitive flexibility in naturalistic contexts.

Activities

The introduction of activities focused on non-verbal emotional expression (e.g., drawing, body expression, or emotion labeling, using images) was a major topic of discussion in FG2. These activities would be useful to convey the idea that the characteristics of inhibited children are respected and valued. Claire explained:

“We want to promote the adaptation of the child to the challenges of the context, to promote social interaction. But we also want to respect the characteristics of the child (...) The intervention program needs to create opportunities for the child to feel accepted, as he/she chooses to express himself/herself, to feel that his/her opinion is valued. If he/she feels valued, the child will have the courage to try new forms of emotional expression (...) that implies verbal communication.”

Due to the acceptability of puppets among young children, FG3 recommended the introduction of activities focused on story completion . Charlotte explained:

“During the sessions on emotionally demanding contents, puppets could be used to simulate situations – for example, two children who refuse to play with another child; then, we could ask children what they think that the child who was rejected by peers should do (...). We could ask them to discover the end of the story (...). I believe that this can be tricky during the first sessions but introducing gradually story completion (...) may be interesting.”

FG1 and FG2 suggested other interactive activities to explain the contents related to emotion-regulation (going inside a shell to calm down) or introducing oneself (remembering the names of each other’s). The use of animation movies was recommended in FG2 to explain the contents related to emotion expression and promote the identification of their body signs.

All groups suggested minor modifications in closing activities, such as introducing culturally-relevant games, changing the name of the graduation party (e.g., bravery or turtle party), or including a relaxation ritual at the end of the sessions.

Materials

FG1 and FG2 agreed with the acceptability of stickers, which are typically appreciated by young children. The two groups emphasized the importance of combining stickers with labeled praises and tailoring them to children’s preferences or specific social behaviors to enhance their significance for children and minimize the risk of social comparison. Conversely, FG3 acknowledged the efficacy of material reinforcement, but criticized its emphasis on short-term extrinsic motivation. Furthermore, FG3 was also concerned with the risk of social comparison and anticipated its negative impact for inhibited children. For example, Rachel stated:

“I am a little bit worried that stickers may have a pervasive effect with inhibited children. Because there is a great pressure in everything they do: they may think – I am here and I’m not even able to receive a sticker. And the negative social comparison may become more important for the child than the focus on what he/she is able to do.”

FG3 agreed with that labeled praise for child’s effort to approach social situations would be sufficient or suggested the introduction of a group sticker for achieving common objectives or completing cooperative tasks. Charlotte explained:

“I like the idea that the group of children may receive a sticker (...). One of the developmental tasks during the preschool years is the belonging to a group, for the first time (...) We may reinforce this sense of group belonging.”

Instead of written feedback sheets for parents, FG2 and FG3 recommended the development of a bravery passport or booklet. This format would allow a better understanding of child’s progress and foster child’s self-confidence. Audrey stated:

“We often use a passport. In this passport, children receive a stamp for their participation in each session (...) Then, we write some feedback for parents (...) This passport may be important, so that children have something to show about their participation (...) and foster their self-esteem”.

Similarly, FG2 suggested minor modifications in the bravery certificate, such as the inclusion of a specific labeled praise or child’s individual strength in a group photography. In addition to written sheets, FG1 recommended the use of individualized strategies to provide feedback to parents and encourage parent-child communication about the intervention program, such as a brief conversation at the end of each session, a weekly telephone call, or an e-mail tailored to the specific needs of each family. These strategies could be especially useful for families from low socioeconomic statuses. FG3 also discussed the development of an app, but some participants anticipated difficulties related to conflicting parental views toward children’s access to electronic devices.

FG3 recommended a greater involvement of children in the preparation and selection of the materials (e.g., drawing the playroom or constructing their own puppets with parents). This would be helpful for inhibited children to feel more secure when exposed to unfamiliar situations and activities during the first intervention sessions. Furthermore, all groups discussed supplementary materials, such as books, family and superhero figures, rule games, or materials that can help children to remember the bravery story (fourth session). FG3 anticipated that some materials may need to be adapted (e.g., preschool calendar) to target the preferences of Portuguese children.

Discussion

This focus group study extends prior research on the perceptions of Portuguese mental health practitioners about the parent component of the Turtle Program (Guedes et al., 2019). Thus, the aim of the present study was to examine the perceptions of psychologists about the child component of the Turtle Program, as a first step before its dissemination in Portugal. Overall, our findings show that psychologists also perceived the intervention objectives, structure and contents of the child component of the Turtle Program as globally acceptable for the Portuguese culture. Participants recommended only minor modifications to enhance children’s acceptance toward BI/AW and positive self-perceptions, give more time to children, strengthen the connection with the preschool context, broaden the focus on contents related to emotional expressiveness and social interaction, and introduce other creative or dramatic play activities and materials.

With respect to the objectives, our findings reveal that Portuguese psychologists seem to be aware of the limitations related to social skills training. In fact, the perspectives of practitioners are consistent with the idea that social skills training may not be necessary or sufficient for all inhibited children, because these children are often able to behave in a socially competent way, but anxiety prevents them from displaying proficient social behaviors (Greco & Morris, 2001). According our theoretical framework (Rubin et al., 2009), participants acknowledge that it is important to intervene on child’s self-perceptions that can be negatively affected by the recognition of child’s less proficient social behaviors. Consistent with the recent integration of experiential approaches in interventions targeting child anxiety (Barrett et al., 2014), participants recommended to combine social skills training and gradual exposure with the promotion of child’s emotional acceptance toward BI/AW. The suggestion to introduce acceptance-based intervention objectives and contents is also in line with the idea that normalizing anxiety-related problems can be particularly relevant among LatinX populations to reduce the stigma related to mental health issues (Pina et al., 2009).

In line with prior evidence on the perceived acceptability of the parent component of the Turtle Program in Portugal (Guedes et al., 2019), Portuguese psychologists recommended the introduction of preliminary, additional and/or follow-up sessions or the enlargement of the time interval between the sessions. This is consistent with the idea that practitioners typically value the importance of giving more time to LatinX populations (Pina et al., 2009) for building rapport and personal discussion. The nature of children’s difficulties focused on the intervention program may have also influenced the findings. In fact, inhibited children typically display an increased emotional and physiological reactivity when exposed to unfamiliar persons, situations and activities (Fox et al., 2005) and can benefit from the gradual exposure to the feared situations (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015). The joint parent-child preliminary contact with the facilitators and the gradual lengthening of the sessions over time can be helpful to build rapport and minimize child’s discomfort when exposed to the novel intervention context. With respect to the extension of the intervention sessions over time, the perspectives of Portuguese practitioners seem to support the idea that booster sessions or training review sessions are important to enhance the generalization in naturalistic contexts (Greco & Morris, 2001).

More specifically, participants discussed the connection of the intervention with the preschool context. The higher representation of developmental psychologists, who work in normative school contexts, may explain why the concerns related to the ecological validity of the controlled intervention context and homogeneous peer group were more apparent in the first focus group. In line with previously identified drawbacks in peer-mediated approaches targeted at social skills training (Greco & Morris, 2001), participants anticipated that inhibited preschoolers may experience difficulties in applying the learned skills at preschool and may be underprepared to cope with the negative reactions of non-inhibited peers. The concerns related to the generalization of the intervention effects to the preschool context may be particularly relevant in the Portuguese culture. In fact, Portugal is one of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] countries, where young children spend more hours in early childhood care and education services, due to the high rate of full-time labor market participation among mothers of children under five (OECD, 2016). Given that preschool is a major ecological context of development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), the perspectives of Portuguese practitioners are in line with prior recommendations aimed at practicing newly learned social skills in naturalistic settings (Greco & Morris, 2001), such as introducing follow-up sessions at preschool, sharing intervention activities and materials with preschool teachers, or prescribing home experiences. These findings support the idea that inhibited children may be placed in a healthier developmental trajectory, when teacher-child relationships are positive, closer and less dependable (Sette, Baumgartner, & Schneider, 2014).

With respect to the structure of the intervention sessions, the views of Portuguese psychologists seem to support that play-oriented techniques are transculturally relevant, especially for young children (Barrett et al., 2014). More specifically, participants acknowledged the advantages of free play for child interest and tolerance toward session length. In fact, the principles of child-centered play have been found to be consonant with LatinX preferences for person-centered, present-focused and spontaneous approaches that cultivate nurturing and proximal interpersonal relationships (Garza & Bratton, 2005). In spite of the advantages of free play, Portuguese psychologists anticipated that group facilitators may need to assume a more active intervention (i.e., guide children to explore the playroom, or suggest play activities), when children arrive during the first sessions. These perspectives are in line with the previously discussed findings, suggesting that inhibited children need to be given more time to adapt to the novel intervention context. This may be especially important in LatinX cultures that are typically less oriented toward the socialization of independence and encouragement of autonomy than North American cultures (Rubin, Oh, Menzer, & Ellison, 2011).

The introduction of snack time in the structure of the sessions was a major topic of discussion in the first focus group. The high proportion of developmental psychologists working in schools may explain their interest on this topic in this group. In fact, mealtimes and other daily routines at preschool have been increasingly recognized as central to promote rich interactions, build relationships and engage in social conversations (Hallam, Fouts, Bargreen, & Perkins, 2016). However, half of the participants recommended to build intervention opportunities during snack time in a sensitive way, giving time to children to know each other and communicate non-verbally during the first sessions. This is consistent with prior evidence, suggesting that non-verbal forms of social and affective communication (e.g., human touch) are frequently more valued than verbal ones in the Portuguese context (Guedes et al., 2019). The perspectives of Portuguese practitioners also support the idea that establishing eye contact to be brave can generate discomfort and need to be adapted in some cultural contexts (Barrett et al., 2014; Sonderreger & Barrett, 2004), using more natural and gradual practice approaches.

The balance between verbal and non-verbal forms of social communication was also discussed, when focusing on the acceptability of the intervention activities and materials. In line with the idea that intervention programs need to build upon child’s strengths (Barrett et al., 2014), participants encouraged the introduction of artistic, body expression and dramatic play activities and materials to convey a sense of acceptance toward BI/AW. Our findings also support that minor culturally-sensitive modifications are often needed in the way how intervention is presented (Pina et al., 2009; Sonderreger & Barrett, 2004) through the inclusion of activities, games and materials that are common in the Portuguese context. The introduction of animation videos for psychoeducational purposes is consistent with prior recommendations to target the preferences of LatinX and Southern European families (Guedes et al., 2019).

The greater emphasis on emotional knowledge and regulation was apparent in the perspectives of Portuguese psychologists, when discussing the intervention contents and the introduction of relaxation activities at the end of the intervention sessions. This is in line with the recent advances toward a transdiagnostic approach (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2018) and with the salience of emotional expressiveness in Southern European cultures (Casiglia, loCoco, & Zappulla, 1998). More specifically, participants recommended to begin the intervention program with a broader focus on emotion knowledge (e.g., connecting emotions to facial, body and behavioural cues, emotion identification, recognition and understanding), with a particular emphasis on social anxiety. These recommendations are in line with the order and type of contents focused on the FRIENDS intervention program (Barrett et al., 2014), which is currently available in Portugal for school-aged children (Pereira et al., 2014). With respect to emotion regulation, participants anticipated the need to go beyond belly breathing training. The questionable efficacy of relaxation training for young children (Comer, Hong, Poznanski, Silva, & Wilson, 2019) and the recent integration of broader experiential approaches (e.g., positive attention and awareness training) in evidence-based interventions targeted at child anxiety (Barrett et al., 2014) may explain these findings.

In line with the salience of sociability in LatinX Southern European cultures, in general (Casiglia et al., 1998) and Portugal, in particular (European Commission, 2012), participants suggested a broader focus on contents related to social interactions. Given that preschool is a major ecological context of development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) for young children in Portugal (OECD, 2016), psychologists emphasized the need to present these contents in a realistic manner, so that children can be prepared to cope with daily social interactions with non-inhibited children in their naturalistic contexts. More specifically, participants anticipated that it would be useful to provide psychoeducation on the typical peer group responses toward inhibited behaviors and to promote a realistic perspective about high-quality friendships. In fact, prior evidence has shown that inhibited children are more likely to be perceived by peers as “easy targets” for victimization and to be excluded from the peer group (Rubin et al., 2018). Within a developmental and transactional approach (Rubin et al., 2009), the development of stable and high-quality friendships can protect inhibited children against unhealthy developmental trajectories. In addition, Portuguese psychologists also recommended the practice of assertiveness and active-hearing skills, like in the FRIENDS program (Pereira et al., 2014). This is consistent with the idea that inhibited children typically assume a passive, avoidant and submissive attitude toward peers that can contribute to maintain the negative transactional cycle and increase the risk of later peer difficulties (Rubin et al., 2009).

With respect to the intervention materials, Portuguese psychologists were somewhat reticent toward the use of material reinforcement (i.e., stickers) during the intervention sessions. Prior research has also found that practitioners acknowledged that the use of tangible rewards is relatively uncommon in the Portuguese culture (Guedes et al., 2019). Furthermore, inhibited children are more likely to think and feel poorly about themselves when comparing themselves with their peers (Rubin et al., 2018). This may explain why Portuguese psychologists anticipated that the use of stickers may increase the risk of negative social comparison between inhibited children, even though ensuring that all children received some stickers based on their individual achievements. To overcome anticipated difficulties, the third focus group suggested the exclusive use of labeled praise and, if needed, the introduction of group stickers. The suggestion to focus on collectivist achievements may reflect the salience of values related to solidarity, equality and support to others in Portugal when compared with the European mean (European Commission, 2012). Alternatively, the first and the second focus groups recommended to tailor stickers to children’s specific preferences or social achievements. These findings are consistent with prior research conducted with LatinX populations, showing the importance of tailoring the intervention to child’s individual needs (Pina et al., 2019). This was also apparent, when discussing the involvement of children in the design of the playroom and the development of a bravery certificate targeted at each child’s strengths.

Our findings also support the need to be mindful toward the use of written handouts for Portuguese parents and to assess literacy as a potential barrier to adhere to this type of materials (Guedes et al., 2019). This may explain why Portuguese psychologists suggested the use of more interactive written formats (e.g., bravery booklet or passport) that can enhance the awareness of children’s progresses. More experienced Portuguese psychologists suggested the use of interpersonal strategies (i.e., individualized e-mail or telephone call) to provide feedback to parents. These interpersonal strategies were also reported as relevant strategies to enhance treatment engagement in prior research conducted with LatinX families living in the USA (Huey & Polo, 2010).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that explored the perceptions of Portuguese psychologists about the acceptability of a child intervention targeted at BI/AW during early childhood. However, some limitations need to be acknowledged. The sample only consisted of female psychologists, who typically display more favourable attitudes toward manualized evidence-based interventions. The group format and the familiarity of the moderator with some participants and between some participants may have contributed to the desirability or inhibition of some responses. Given the purpose of the present study, we conducted a thematic analysis based on a descriptive approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and we did not analyse group interactions. The triangulation with other methods was limited to a self-report questionnaire, developed by the research team. Despite their consistency with qualitative findings, individual responses to the questionnaire may have been influenced by the timing of assessment (i.e., at the end of the group discussion).

Future studies need to overcome these limitations and to explore the perspectives of practitioners about the acceptability of the child component of the Turtle Program in other Southern European countries. Furthermore, the perspectives of families about the intervention program need to be collected and compared with those of practitioners. This can inform tailoring needed for implementing child intervention targeted at BI/AW during early childhood in Southern European cultures.

References

Attili, G., Vermigli, P., & Schneider, B. H. (1997). Peer acceptance and friendship patterns among Italian children within a cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21, 277-288. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/016502597384866 [ Links ]

Barrera, M., Castro, F. G., Strycker, L. A., & Tooberg, D. J. (2013). Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology, 81, 196-205. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0027085 [ Links ]

Barrett, P. M., Cooper, M., & Guarjado, J. G. (2014). Using the FRIENDS Programs to promote resilience in cross-cultural populations. In S. Prince-Embury & D. Saklofske (Eds.), Resilience interventions for youth in diverse populations (pp. 85-108). New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Barstead, M., Danko, C., Chronis-Tuscano, A., O’Brien, K., Coplan, R., & Rubin, K. H. (2018). Generalization of an early intervention for inhibited preschoolers to the classroom setting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 2943-2953. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1142-0

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 793-828). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [ Links ]

Caldas-Almeida, J., & Xavier, M. (2013). Epidemiological national study about mental health: First report. Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Universidade de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Carter, S. L. (2008). A distributive model of treatment acceptability. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 43, 411-420. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23879672 [ Links ]

Casiglia, A. C., LoCoco, A., & Zappulla, C. (1998). Aspects of social reputation and peer relationships in Italian children: A cross-cultural perspective. Developmental Psychology, 34, 723-730. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.4.723 [ Links ]

Chase, T., & Peacock, G. G. (2017). An investigation of factors that influence acceptability of parent training. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 1184-1195. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0644-x [ Links ]

Chen, X., & French, D. C. (2008). Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 591-616. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093606

Chen, X., French, D. C., & Schneider, B. H. (2006). Culture and peer relationships. In X. Chen, D. C. French, & B. H. Schneider (Eds.), Peer relationships in cultural context. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Chen, X., He, Y., De Oliveira, A. M., lo Coco, A., Zappulla, C., Kaspar, V., . . . deSousa, A. (2004). Loneliness and social adaptation in Brazilian, Canadian, Chinese and Italian children: A multi-national comparative study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1373-1384. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00329.x [ Links ]

Chronis-Tuscano, A., Danko, C., Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R. J., & Novick, D. (2018). Future directions for research on early intervention for young children at risk of social anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47, 655-667. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1426006 [ Links ]

Chronis-Tuscano, A., Degnan, K. A., Pine, D. S., Perez-Edgar, K., Henderson, H. A., Diaz, Y., . . . Fox, N. A. (2009). Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 928-935. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df [ Links ]

Chronis-Tuscano, A., Rubin, K. H., O’Brien, K. A., Coplan, R. J., Thomas, R., Dougherty, L. R., . . . Wimsatt, M. (2015). Preliminary evaluation of a multi-modal early intervention for inhibited preschoolers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 534-540. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039043

Comer, J. S., Hong, N., Poznanski, B., Silva, K., & Wilson, M. (2019). Evidence base update on the treatment of early childhood anxiety and related problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 48, 1-15. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1534208 [ Links ]

Comissão Nacional de Promoção dos Direitos e Proteção de Crianças e Jovens. (2018). Annual evaluation report of the CPCJ activities. Lisboa: Author. [ Links ]

Coplan, R. J., Schneider, B. H., Matheson, A., & Graham, A. (2010). Play skills for shy children: Development of a social facilitated play early intervention program for extremely inhibited preschoolers. Infant Child and Development, 19, 223-237. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.668 [ Links ]

Correia, J., Santos, A. J., Freitas, M., Ribeiro, O., & Rubin, K. H. (2014). As relações de pares de jovens socialmente retraídos. Análise Psicológica, XXXII, 467-479. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.870 [ Links ]

Danko, C. M., O’Brien, K. A., Rubin, K. H., & Chronis-Tuscano, A. (2018). The Turtle Program: PCIT for young children displaying behavioral inhibition. In L. N. Niec (Ed.), Handbook of parent-child interaction therapy: Innovations and applications for research and practice (pp. 85-98). New York: Springer. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-97698-3_6

European Commission. (2012). The values of European. Brussels: Author. [ Links ]

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., & Boggs, S. R. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 215-237. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410701820117 [ Links ]

Fox, N., Henderson, H. A., Marshall, P. J., Nichols, K. E., & Ghera, M. M. (2005). Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 235-262. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532 [ Links ]

Freitas, M., Santos, A. J., Ribeiro, O., Daniel, J., & Rubin, K. H. (2019). Prosocial behavior and friendship quality as moderators of the association between anxious withdrawal and peer experiences in Portuguese young adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2783. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02783 [ Links ]

Garza, Y., & Bratton, S. C. (2005). School-based child-centered play therapy with hispanic children: Outcomes and cultural consideration. International Journal of Play Therapy, 14, 51-80. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088896 [ Links ]

Guedes, M., Coelho, L., Santos, A. J., Veríssimo, M., Rubin, K. H., Danko, C., & Chronis-Tuscano, A. (2019). Perceptions of Portuguese psychologists about the acceptability of a parent intervention targeted at inhibited preschoolers. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 4, 1-17. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2018.1555443 [ Links ]

Greco, L. A., & Morris, T. L. (2001). Treating childhood shyness and related behavior: Empirically evaluated approaches to promote positive social interactions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 4, 299-318. [ Links ] Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1013543320648

Hallam, R. A., Fouts, H. N., Bargreen, K. N., & Perkins, K. (2016). Teacher-child interactions during mealtimes: Observations of toddlers in high subsidy child care settings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44, 51-59. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-014-0678-x [ Links ]

Huberman, A. M., & Miles, M. B. (1994). Data management and analysis method. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 428-444). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Huey, S. J., & Polo, A. J. (2010). Assessing the effects of evidence-based psychotherapies with ethnic minority youths. In J. R. Weisz & E. Kazdin (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (pp. 451-465). New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Kazdin, A. E. (1980). Acceptability of alternative treatments for deviant child behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 13, 259-273. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1980.13-259 [ Links ]

Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (5th ed.). New York: Sage. [ Links ]

Lau, E. X., Rapee, R. M., & Coplan, R. J. (2017). Combining child social skills training with a parent early intervention program for inhibited preschool children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 51, 32-38. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.08.007 [ Links ]

Lennox, D. B., & Miltenberger, R. G. (1990). On the conceptualization of treatment acceptability. Education and Training in Mental Retardation, 25, 211-224. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23878597.pdf?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [ Links ]

Li, Y., Coplan, R. J., Wang, Y., Yin, J., Zhu, J-J., Gao, Z., & Li, L. (2016). Preliminary evaluation of a social skills training and facilitated play early intervention programme for extremely shy young children in China. Infant and Child Development, 25, 565-574. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1959 [ Links ]

Mejia, A., Calam, R., & Sanders, M. R. (2015). Examining the fit of evidence-based parenting programs in low resources settings: A survey of practitioners in Panama. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 2262-2269. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0028-z [ Links ]

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] (2016). Society at a glance: OECD social indicators. Paris: Author. [ Links ]

Pereira, A. I., Marques, T., Russo, V., Barros, L., & Barrett, P. (2014). Effectiveness of the FRIENDS for Life in Portuguese schools: Study with a sample of highly anxious children. Psychology in the Schools, 51, 647-657. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21767 [ Links ]

Pina, A., Holly, L. E., Zerr, A., & Rivera, D. (2014). A personalized and control systems approach to target anxiety in the contexts of cultural diversity. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 442-453. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2014.888667 [ Links ]

Pina, A., Polo, A. J., & Huey, S. J. (2019). Evidence-based psychosocial interventions for ethnic minority youth: A 10-year update. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48, 179-202. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1567350 [ Links ]

Pina, A., Villalta, I. K., & Zerr, A. (2009). Exposure-based cognitive behavioral treatment of anxiety in youth: An emerging culturally-prescriptive framework. Behavioral Psychology/Psicologia Conductal, 25, 111-135. [ Links ]

Pincus, D. B., Eyberg, S. M., & Choate, M. L. (2005). Adapting parent-child interaction therapy for young children with separation anxiety disorders. Education and Treatment of Children, 28, 163-181. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/42899839 [ Links ]

Reimers, T. M., Wacker, D. P., & Koeppl, G. (1987). Acceptability if behavior interventions: A review of the literature. School Psychology Review, 26, 212-227. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ356304 [ Links ]

Rubin, K. H., Bowker, J. C., Barstead, M. G., & Coplan, R. J. (2018). Avoiding and withdrawing from the peer group. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships and groups (2nd ed., pp. 322-346). New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R. J., & Bowker, J. C. (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 141-171. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642 [ Links ]

Rubin, K. H., Oh, W., Menzer, M. M., & Ellison, K. (2011). Dyadic relationships from a cross-cultural perspective: Parent-child relationships and friendship. In X. Chen & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Socioemotional development in cultural context (pp. 208-238). New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Santos, A. J., Monteiro, L., Sousa, T., Fernandes, C., Torres, N., & Vaughn, B. (2015). Low social engagement: Implications for children psychosocial adjustment in the preschool context. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 28, 186-193. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7153.201528120 [ Links ]

Sette, S., Baumgartner, E., & Schneider, B. H. (2014). Shyness, child-teacher relationships and socio-emotional adjustment in a sample of Italia preschool-aged children. Infant and Child Development, 33, 323-332. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1859 [ Links ]

Smith, K. A., Hastings, P. D., Henderson, H. A., & Rubin, K. H. (2019). Multidimensional emotion regulation moderates the relation between behavioral inhibition at age 2 and social reticence with unfamiliar peers at age 4. Journal of Abnormal Clinical Psychology, 47, 1239-1251. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-00509-y [ Links ]

Sonderegger, R., & Barrett, P. M. (2004). Assessment and treatment of ethnically diverse children and adolescents. In P. M. Barrett & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), Handbook of interventions that work with children and adolescents (pp. 89-112). West Sussex, England: Wiley. [ Links ]

Vaughn, B., Santos, A. J., Monteiro, L., Shin, N., Daniel, J. R., Krzysik, L., & Pinto, A. (2016). Social engagement and adaptive functioning during early childhood: Identifying and distinguishing among subgroups differing with regard to social engagement. Developmental Psychology, 52, 1422-1434. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dev0000142 [ Links ]

Wall, K., & Gouveia, R. (2014). Changing meanings of family in personal relationships. Current Sociology, 62, 352-373. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113518779 [ Links ]

Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis, 11, 203-214. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203 [ Links ]

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Maryse Guedes, William James Centre for Research, ISPA – Instituto Universitário, Rua Jardim do Tabaco, 34, 1149-041 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: maryseguedes@gmail.com

This study is part of the research project “Adaptation and evaluation for Portugal of the early intervention multi-modal intervention Turtle Program”, conducted by the R&D William James Center for Research, ISPA. This project is co-funded by the Foundation Calouste Gulbenkian (Programa Academias Gulbenkian do Conhecimento, process nº 222926). Maryse Guedes, is supported by a scholarship from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (SFRH/BPD/114846/2016).

Submitted: 15/01/2018 Accepted: 26/06/2019