Over the past three decades, there has been a growing interest in the study of socialization of emotion, as it refers to the socialization of children’s understanding, experience, expression, and regulation of emotion (Eisenberg et al., 1998). This processes of socializing children’s emotion happens primarily within the family context, expanding to other socializers (e.g., teachers, peers) through development (Eisenberg et al., 1998).

Crosswise ESPP can be supportive (e.g., comforting, teaching constructive means of coping) or unsupportive (e.g., punishing or minimizing) of the child’s expression of emotion (Eisenberg et al., 1998). Non-supportive reactions are associated with negative social and emotional outcomes for children (Gottman et al., 1996). On the contrary, supportive reactions to children’s display of negative emotion are associated with child’s positive outcomes (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1999).

The way parents socialize their child’s emotion depends on their philosophy about emotion. Gottman et al. (1996) indicate that parents may tend to be dismissive or coachers of their child emotion, depending on their meta theory of emotion, defined as “an organized set of feelings and thoughts about one’s own emotions and one’s children’s emotions” (Gottman et al., 1996, p. 243). The parents’ philosophy about emotions and corresponding ESPP are influenced by culture and related to the parent and child’s gender (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1998), child developmental stage (e.g., Gottman et al., 1997) and the targeted emotion (Garside & Klimes-Dougan, 2002; O’Neal & Magai, 2005). Concerning ESPP changes across development, some studies have pointed out that as children get older, parent’s expectations concerning their emotional competencies increase, and those expectations reflect in parents ESPP (Cassano et al., 2007; Dix, 1991), with parents tending to be less supportive (O’Neal & Magai, 2005).

Adolescence is a sensitive developmental period for both normative and mal-adaptive patterns of development, as it is a crucial phase for the reorganization of regulatory systems, which entails both risks and opportunities. In this stage, puberty plays a central role in restructuring some body systems and influences social information-processing. Also, changes in the prefrontal cortex with enhanced communication between this region and other brain regions, which are primordial to executive functioning, operate in this period (Steinberg, 2005). Although adolescence is a developmental phase with evident emotional and social defies associated to emotion regulation and psychological adjustment, little is known about ESPP in this period, as most studies on emotion socialization and emotion regulation focused on infancy and early childhood (Morris et al., 2007). While this is a developmental period in which children are less dependent on their parents and the role of peers becomes more significant, parents remain influential in their emotional lives (Miller-Slough & Dunsmore, 2016; Morris et al., 2007).

Research on adolescence mostly focuses on emotional and behavioural outcomes such as internalizing/externalizing and depressive symptoms, rather than optimal development. Some of these studies sustain the mediatory role of emotion regulation in the ESPP influence to child’s outcomes. For example, Yap et al. (2008) showed that adolescents whose mothers respond to positive affect in an invalidating manner, displayed more emotionally dysregulated behaviours and reported both greater frequency of mal-adaptive emotion regulation strategies and higher levels of depressive symptoms. Also, Buckholdt et al. (2014) reported that mothers’ invalidating responses to their youth’ negative emotions were indirectly related to higher youth externalizing and internalizing symptoms through adolescent emotion dysregulation.

Most of the research on emotion socialization has centred on mothers, with a few studies including both mother and father. General similarities have been pointed out in the way mothers and fathers socialize emotion in their child, with both parents more likely to exhibit positive rather than negative ESPP (e.g., Garside & Klimes-Dougan, 2002).

Also, important differences have been shown in the literature. Compared to fathers, mothers are identified as being more aware and coaching of their school-aged child (e.g., Cassano et al., 2007). Complementarily, fathers are observed as being less involved in their child’s emotional rearing and to neglect more their displays of negative emotion (e.g., Garside & Klimes Dougan, 2002). Additionally, ESPP of mother and father can vary according to the discrete emotion displayed by the child. For instance, when fathers use coaching strategies, they are more likely to use them to coach anger then sadness (Gottman et al., 1997) while mothers tend to coach all emotions.

Further, some studies reveal that mothers and fathers use different ESPP for boys and girls depending on the displayed emotion, with fathers being more differentiated than mothers in their ESSP towards their sons and daughters, as fathers are most likely to encourage and reinforce the expression of gender-stereotyped emotion (e.g., Garside & Klimes-Dougan, 2002). In this regard, fathers are particularly punitive in response to their sons’ displays of vulnerable negative emotions like sadness and fear (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1999) and reward their daughters more for expressing the same emotions (e.g., Garside & Klimes-Dougan, 2002).

In addition to differences and similarities in ESPP of mothers and fathers, the consistency/inconsistency between their ESPP appears to play an important role in child adjustment. Brand and Klimes-Dougan (2010) describe two different positions in the literature, in respect to consistency between parents, one defending parental consistency regarding optimal parenting practices being necessary to buffer children from negative stressors and the other asserting that “one-good parent” is sufficient. They underline the consistent finding in the literature that two parents practicing poor parenting strategies is related to poor adolescent adjustment. The research in this area relates mostly to general parenting practices and there is a need for evidence related specifically to ESPP.

As previously mentioned, in respect of research interest on emotion socialization, some areas remain poorly explored, as most studies focus on early childhood and only on mothers. Therefore, more information on other developmental periods like adolescence is needed, as there is evidence that parents remain important agents of socialization in this phase. Also increased knowledge on ESPP of both parents is required, particularly in adolescence, due to the paucity of studies that include the father in this period. Further, it is important to enhance knowledge about the specific contribution of ESPP of mother and father to enable a better understanding of their influence on adolescent normative development and on psychopathology, including the comprehension of how they converge or diverge in their ESPP and the influence of this (in)consistency on adolescents’ adjustment.

Objectives

The purpose of this systematic review is firstly to examine the current evidence on similarities and differences between mothers and fathers of adolescents concerning emotion socialization practices and secondly to identify their association with mental health and other adjustment dimensions in adolescents. Thirdly, we intend to analyse differences between high risk and low-risk groups for adolescents’ mental health problems in relation to ESPP of mothers and fathers. Fourthly, we aim to analyse the impact of consistency versus inconsistency between the ESPP of mothers and fathers. In spite of the various parenting dimensions involved in emotion socialization, in this review, we will focus on parenting practices specifically related to emotion and emotion management, as exposed in the tripartite model proposed by Morris et al. (2007), including parent’s emotion coaching and reactions to emotion.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The articles were required to fulfil the following criteria: (1) empirical study focusing on emotion socialization practices of adolescents’ parents (2) included fathers and mothers and analysed data independently for fathers and mothers; (3) included a sample of parents of children from 10 to 18 years old; (4) published in English in a peer reviewed journal; (5) published after 1990, the decade when the seminal studies on emotion socialization were developed (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 1998; Gottman et al., 1996).

Information sources

A literature search was conducted for studies published in English from January 1990 to March 2019. Databases used were PsycINFO, Education Source, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, ERIC, PsycARTICLES.

Search strategy and study selection

The following search terms and Boolean operators were used: (Parent emotion*) OR (parent* meta-emotion) OR (parent* co-regulation) OR (parent* regulation) OR (parent* dysregulation) OR (father emotion*) OR (father* meta-emotion) OR (father* co-regulation) OR (father* regulation) OR (father* dysregulation) OR (mother emotion*) OR (mother* meta-emotion) OR (mother* co-regulation) OR (mother* regulation) OR (mother* dysregulation) AND Mother AND Father AND (Adolescent* or teen* or youth).

Methodological quality of the studies

Methodological quality of the studies was assessed following an adaptation of selected guidelines from the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. The following criteria were adopted: (a) description of relevant sample characteristics (b) recruitment procedures adequately described (c) reliable measures of ESPP (d) power calculation reported and study adequately powered to detect hypothesized relations (e) description of statistical methods.

Results

Results of the search

The search following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) initially produced 969 papers. Studies were de-duplicated (969-590=379) and screened by title and abstract, resulting in the exclusion of 340 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria.

From the 39 full texts examined, 32 were eliminated because they: analysed fathers’ and mothers’ data together; did not differentiate the results for the adolescent sample; focused on general parenting practices, instead of emotion socialization parental practices.

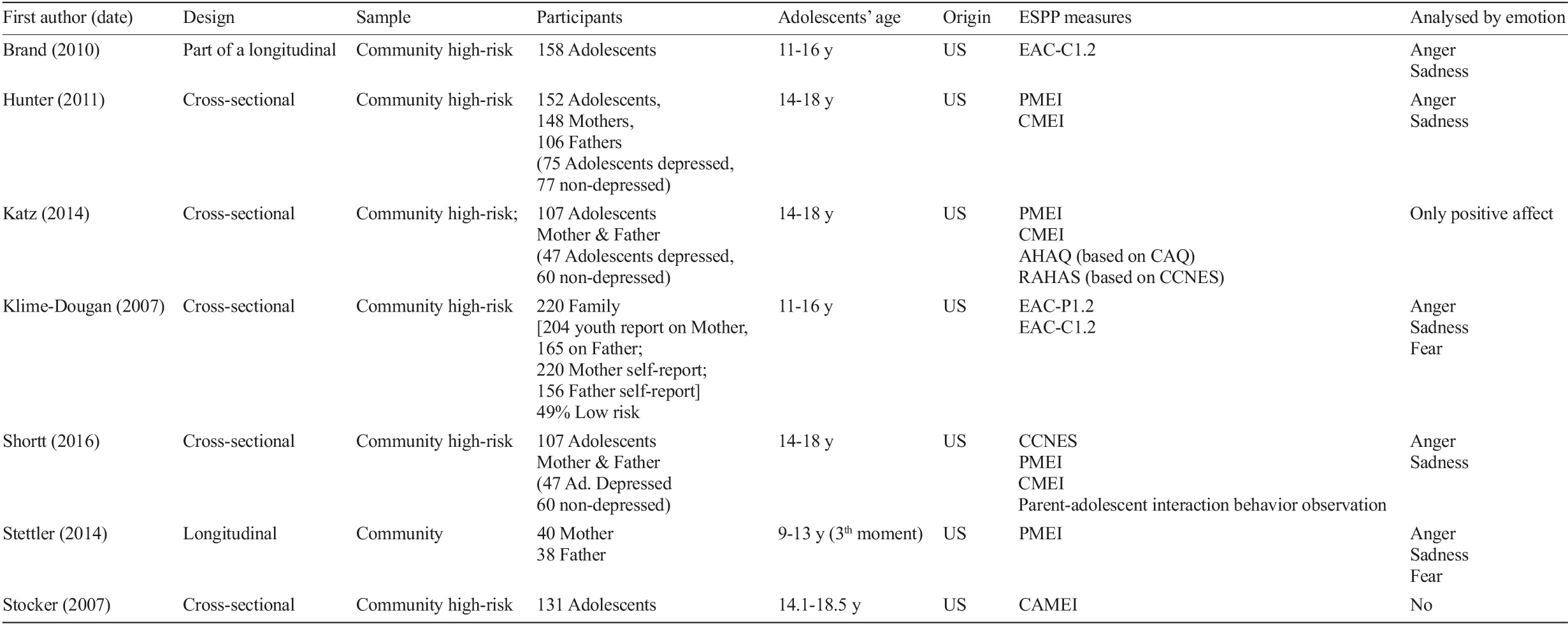

Finally, 7 eligible articles were identified. All studies were from the USA. The majority of the studies were conducted using community high-risk samples, with adolescents screened for depressive disorders or a range of behavioural internalizing/externalizing problems. The sample dimension was variable (minimum 40 and maximum 220), and most of the studies included as informants’ adolescents and their mother and father; however, one study included just the mother and the father and two studies included only the adolescents. Youth’s age range was between 10 and 18. One of the studies had a longitudinal design.

To evaluate Emotion Socialization Practices (ESP), studies resorted to various measures such as questionnaires (e.g., CCNES; Fabes et al., 2002, as cited in Shortt et al., 2016), open-ended interview (e.g., PMEI; Katz & Gottman, 1986, as cited in Katz et al., 2014) and observational measures (e.g., code by The Living in Family Environments system LIFE; Hops et al., 1995, as cited in Shortt et al., 2016).

Some studies identified differences between mothers’ and fathers’ ESPP in specific groups (e.g., depressed adolescents) (Katz et al., 2014; Klimes-Dougan et al., 2007; Shortt et al., 2016), while some others identified differences between mothers’ and fathers’ ESPP that varied as a function of adolescents’ sex, the reporter (child, mother or father) (Klimes-Dougan et al., 2007) and/or the emotion studied (e.g., sadness, anger, fear) (Hunter et al., 2011; Klimes-Dougan et al., 2007; Shortt et al., 2016; Stettler & Katz, 2014). Table 1 describes the main characteristics of the studies.

Methodological quality of the studies

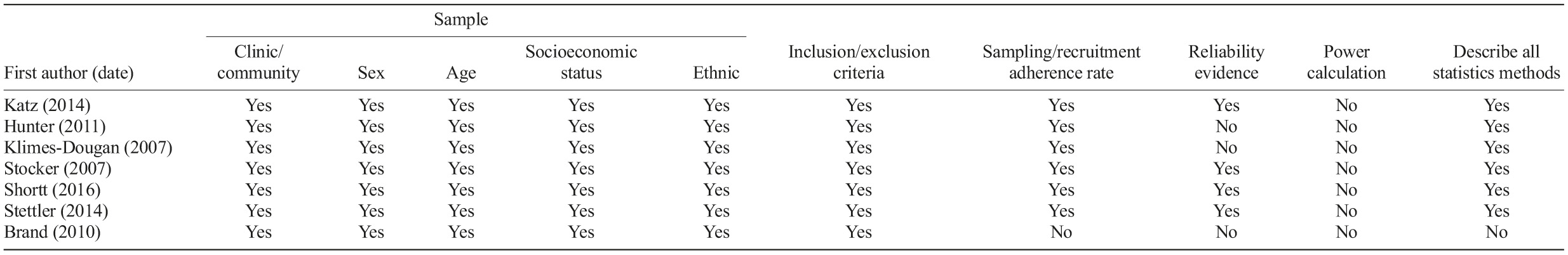

The methodological quality of each study is displayed in Table 2. In general, the studies presented good methodological quality. The least fulfilled criteria were power analysis and sample size estimation, which were not presented in any study. Internal consistency data was presented for the scales measuring ESPP in the study sample for all but one study, and in two studies, reliability score was not adequate for some of the scales. Only one of the studies did not describe all the statistical methods.

Differences between ESPP practices of mother and father

Three studies reported on differences between ESPP practices of mother and father. Klimes-Dougan et al. (2007) examined how mothers and fathers socialize emotion in their adolescent sons and daughters, who exhibit internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, assessing parental responses to their children’s displays of sadness, anger and fear with a multi-informant design. They assessed five emotion socialization strategies: two positive, reward and override; three negative, punish, neglect and magnify. Expected differences were identified for both positive and negative ESPP. On the one hand, mothers showed generally more positive ESPP than fathers - mothers used reward more frequently for all the analysed emotions and used override more frequently for anger and fear (only in youth report) - with exception for fathers being higher than mothers for override of sadness (only in parent report). On the other hand, fathers exhibited more negative ESPP than mothers: fathers neglected more frequently child’s expression of all three emotions (child report) and punished for sadness and fear (parent report). The exception appears to be mothers magnifying more than fathers the child’s expression of sadness and fear and also of anger (only on parent report).

The study of Stettler and Katz (2014) had a longitudinal design and compared meta-emotion philosophy (MEP) of mothers and fathers, over the course of the child’s development, from pre-school to early adolescence, when the child was 5, 9 and 11 years old. The practices studied within the MEP were awareness, acceptance and coaching and were studied in relation to three kinds of negative emotion (anger, sadness and fear). The authors were able to find some similarities and some differences between ESPP of mothers and fathers in pre-adolescence. Therefore, in 5 of the 9 practices measured there were significant differences between the mother and father, with the mother showing higher coaching of all three emotions, acceptance of fear and awareness of anger. Stocker et al. (2007) examined associations between parents’ emotion coaching and emotion expressiveness, and adolescents’ internalized/externalized symptomatology. We will focus on the results for emotion coaching, as an ESPP. Results reveal that mothers and fathers were more supportive and accepting of adolescents’ negative emotions than they were dismissive, punitive or ignoring. Also mothers presented significantly more emotion coaching practices then fathers.

Association between ESPP of mothers and fathers and adolescent mental health and other adjustment dimensions

The associations between ESPP of mothers and fathers and adolescent mental health and other adjustment dimensions were analysed by only two studies. Hunter et al. (2011) examined associations between parent and adolescent meta-emotion philosophies (MEP) and tested adolescent depressive status as a moderator of the relationship between parents and adolescents’ MEP. The authors studied two types of parents’ MEP: MEP about their own emotions and MEP about their children’s emotions. They did not find significant associations between adolescents’ MEP and parents’ self-directed MEP, but child-direct MEP were associated with adolescents’ MEP. Results of the regression analysis with the total sample showed that in this model, fathers’ child-directed MEP predicted adolescent MEP, but mothers’ child-directed MEP did not. Mothers’ child-directed MEP only predicted adolescents’ MEP in the depressed group, with adolescent depressive status functioning as a moderator. Specifically, mothers’ coaching MEP towards negative emotions of their depressed child was associated with the adolescents having more positive philosophies about their own negative emotion. The study of Stocker et al. (2007) revealed that both the mother’s and father’s emotion coaching were negatively linked to internalizing symptoms, but on the contrary, neither the mother’s nor the father’s emotion coaching was significantly associated with the adolescents externalizing problems.

ESPP of father and mother in regard to adolescent’s mental health status differences

Three studies were found referring to adolescents’ mental health status differences in regard to ESPP of father and mother. Katz et al. (2014) compared parental socialization of adolescents’ positive affect (PA) in families of depressed and healthy adolescents. For positive ESPP, differences were identified between parents of the depressed group and parents of the non-depressed group, with the same direction for mother and father. Results show a lower acceptance in parents of depressed youth and higher coaching in parents of depressed boys than parents of healthy boys. Also, differences in positive ESPP by group status were found only for fathers. Fathers of depressed youth were less likely to capitalize PA and showed less engagement and encouragement of positive activities than fathers of healthy youth.

For negative ESPP, both mother and father (adolescent report) of healthy youths used less minimizing and negative reactions than parents of depressed youth (effect noted for fathers in mother’s report), with the effect being stronger for fathers than mothers.

Shortt et al. (2016) aimed to explore parent emotion socialization processes associated with adolescent unipolar depression disorder. The study evaluated positive and negative ESPP for two different negative emotions (sadness and anger). The authors used the same sample of the Katz et al. (2014) study. For positive practices, they found differences between parents of the depressed group and parents of the non-depressed group, with similar results for mother and father. Parents of depressed youth reported less problem-focused reactions than parents of healthy youth in relation to sadness and anger. Parents of depressed youth in relation to sadness also reported less coaching strategies and less acceptance (only for boys). Nonetheless, some effects were found only for the father, with fathers of depressed boys being more aware of sadness and anger than fathers of healthy boys. For negative practices, there were some differences between the two groups, only for the fathers. Fathers of depressed youth were more likely to punish sadness than fathers of healthy youth and more likely to punish and minimize anger, but only for girls. An effect was found only for mothers, with mothers of depressed boys more likely to punish anger than mothers of healthy boys. Further, in the observed parent-adolescent interaction, parents of adolescents with depressive disorder were more likely then parents of adolescents without depressive disorder, to show anger in response to the adolescent’s anger and also to show anger vis-a-vis boy’s sadness.

Klimes-Dougan et al. (2007) also noted effects related to adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. For anger, parents of youth presenting problems were reported to use less reward, more punishment, and more magnify, than did parents of adolescents in the non-problem group. For magnification of anger, there was a three-way interaction. That is, for non-problem boys, fathers used low levels of magnify in comparison to non-problem girls (mother report) and problem boys (mother and father report), whereas mothers used high levels of magnify with their adolescent girls who exhibited problems in comparison to problem boys (father report) and non-problem girls (mother and father report).

Further, the authors explored the link between specific types of youth problems and emotion socialization approaches. They classified youth into four groups: non-problem, internalizing problems, externalizing problems and co-morbid problems. The results reveal that reward was used least often and neglect the most often in socializing sadness and fear in youth with co-morbid and externalizing problems relative to controls.

Impact of consistency versus inconsistency between ESPP of mother and father

In our review, only one study focused on the interaction between ESPP of mother and father. Brand and Klimes-Dougan (2010) presented an empirical study on the importance of parental consistency in ESPP by evaluating adolescents from two-parent families, examining whether the coordinated emotion socialization of mothers and fathers were linked with the development of internalizing and externalizing problems in their adolescent children. The authors targeted two emotions, sadness and anger. Parents were classified as high or low on the positive and negative summary scales for each emotion based on median splits scales. Parental pairs were placed into seven groups based on their socialization classification. Results revealed that in general, frequent use of negative and also infrequent use of positive ESPP by both parents was associated with higher levels of symptomatology, with one exception in the group of parents who were consistent in the infrequent use of both positive and negative responses, in which no links with psychopathology were identified.

The pattern of results varied for each emotion. Concerning sadness, results showed that frequent use by both parents of negative ESPP was associated with higher levels of adolescent internalizing symptomatology, with the exception of the group of parents who were consistent in the frequent use of both positive and negative responses where no relation with symptomatology was identified. Also, infrequent use of positive strategies by both parents was associated with higher levels of adolescent internalizing symptomatology. No links were identified for externalizing symptomatology. Regarding socialization of anger, frequent use of negative and also infrequent use of positive strategies by both parents was associated with higher levels of adolescent internalizing and also externalizing symptomatology, as did perceiving both parents as frequently using positive and negative strategies. Unequal to sadness, the use of frequent positive and infrequent negative responses by only one parent was also associated with higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology.

Discussion

Concerning our first intent, it was possible to identify some similarities and some differences between ESPP of mothers and fathers towards their adolescent child. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Garside & Klimes Dougan, 2002), both mothers and fathers were more supportive and accepting of adolescents’ negative emotions than they were dismissing, punitive or ignoring (Stocker et al., 2007).

The differences noted in the way the mother and father respond to their child’s negative emotions reveal that in general, mothers are more involved in their adolescents’ emotional life, showing more supportive ESPP and that fathers use more negative ESPP. Mothers accepted fear, were aware of anger (Stettler & Katz, 2014), coached (Stettler & Katz, 2014; Stocker et al., 2007) and rewarded globally negative emotions more than fathers and fathers rather overlooked or ignored their adolescent children’s negative emotions (Klimes-Dougan et al., 2007). These findings are consistent with those in the literature for other development stages that evidenced that mothers are more aware and coaching of their school-aged child (e.g., Cassano et al., 2007).

As for our second objective, identifying the association of maternal and paternal ESPP with mental health and other adjustment dimensions in adolescents, some important results emerged. Concerning adolescents’ philosophies about their own negative emotion, the impact of child-direct MEP of father and mother differs. Fathers’ child-directed MEP was found to predict child MEP for adolescents in general, while mothers’ child-directed MEP only predicted adolescent MEP in the depressed group. Therefore, fathers make unique contributions to their adolescent’s beliefs about their emotion. Adolescent depressive status functioned as a moderator only for relationships between mothers’ child-directed MEP and adolescent MEP (Hunter et al., 2011), suggesting that mother´s beliefs about emotion are particularly important to the development of adaptive emotional beliefs in depressed adolescents.

Regarding adolescent’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms, Stocker et al. (2007) study revealed that both mother’s and father’s emotion coaching were negatively linked to internalizing symptoms, but on the contrary, neither mother’s nor father’s emotion coaching was significantly associated with adolescent’s externalizing problems. The link found between coaching and internalizing symptoms matches previous literature (e.g., O’Neal & Magai, 2005), however, the lack of association between parental coaching and externalizing problems was unexpected. One possible explanation is that the results were not analysed independently for distinct emotions (sadness and anger). There are some studies revealing that discriminated emotions are linked to distinct ESPP and with differentiated outcomes (e.g., O’Neal & Magai, 2005). Also the (in) consistency of parental ESPP patterns might have an important role in these results. These aspects will be further debated during this discussion.

In response to our third intent, to analyse the ESPP of mothers and the fathers in regard to the differences relating to risk and non-risk groups for adolescent’s mental health, results show some differences between groups for both parents’ ESPP and some differences only for the mother’s or father’s ESPP. Concerning positive emotions, mothers and fathers present the same patterns of differences, with higher negative ESPP and less positive ESPP in parents of depressed youth than parents of healthy youth (Katz et al., 2014). Complementarily, concerning negative emotions mothers and fathers present similar results, with parents of depressed youth engaged in less positive and more negative practices, than parents of healthy youth (Shortt et al., 2016). These results converge with previous investigation reporting that acceptance of emotions is especially important during adolescence, functioning as a protective factor in relation to the development of depressive symptomatology, as adolescents whose parents are more accepting and supportive of their negative emotions have less internalizing symptoms than adolescents whose parents are less accepting or more dismissing, avoidant or punitive of their emotions (e.g., O’Neal & Magai, 2005). These findings also combine with the evidence that mothers’ invalidating responses to youth’s negative emotions were linked to higher youth internalizing symptoms (e.g., Buckholdt et al., 2014) as well as the data on emotion coaching by mothers and fathers of adolescents being negatively related to the adolescents’ internalizing symptoms (Stocker et al., 2007).

Notwithstanding the similarities in the way both parents behave, some differences by group status were found only for the father, evidencing that fathers of depressed youth are less likely to display positive ESPP towards PA and most likely to react negatively to PA than fathers of healthy youth (Katz et al., 2014). These results add knowledge to the scanty previous research on PA, confined to mothers, that revealed the importance of negative ESPP directed to PA for the adolescent’s symptomatology (e.g., Yap et al., 2008).

One other issue that emerged in some of the results found in our review indicates a phenomenon pointed out by some authors (e.g., O’Neal & Magai, 2005; Sanders et al., 2015): that the association of parental ESPP to psychopathology outcomes in adolescents might vary with the targeted discrete emotion. As Klimes-Dougan et al. (2007) noted, in response to sadness, parents of adolescents who exhibited internalizing and/or externalizing problems used fewer supportive strategies and, in response to anger, were more likely to respond with negative ESPP than parents of non-problem youth.

Concerning our fourth intent, to analyse the impact of consistency versus inconsistency between ESPP of mother and father, results reveal that in general, frequent use of negative ESPP and also infrequent use of positive ESPP by both parents was associated with higher levels of symptomatology. The pattern of results varied for each emotion (sadness and anger), showing that frequent use of negative ESPP by both parents and infrequent use of positive ESPP by both parents were associated with higher levels of adolescent internalizing symptomatology for ESPP related to sadness and with both internalizing and externalized symptomatology for ESPS towards anger. One exception was noted for parents who were consistent in the frequent use of both positive and negative ESPP in relation to sadness, where no association with symptomatology was identified. This exception can represent a buffer effect previously described in the literature (e.g., Lunkenheimer et al., 2007) that positive ESPP might have on negative ESPP. Additionally, contrary to sadness, for the socialization of anger, it was not enough to have only one parent with optimal socialization strategies, counterpointing the “one-good parent” position in the literature. Further, for anger, perceiving both parents as frequently using positive ESPP was not enough to face the negative effects of two parents who also frequently resort to negative ESPP. Parallel and frequent use of positive ESPP with infrequent use of negative ESPP by both parents seems to be needed to promote better regulation of anger in adolescents, preventing higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. These results are unique in analysing the consistency effect of ESPP of mothers and fathers towards sadness and anger and therefore, more studies should be developed to complement these findings.

These findings give important clues for intervention, as they evidence the importance of the ESPP of both the mother and father and the combined effect of their ESPP on adolescents’ mental health, indicating that it is important to include both parents in intervention programmes targeted at promoting adolescents’ mental health. Further, it is important to take into consideration the specificity of different discrete emotions in the socialization process of emotions.

Limitations and future research

One limitation that can be attributed to this review is that we included only studies published in peer-reviewed journals. This decision offers, on the one hand, a guarantee of the quality, but on the other hand, may increase the bias of reporting studies that found significant effects. Secondly, the exclusive use of English-language studies published during or after the year 1990 might have led to the exclusion of relevant evidence.

Research examining ESPP of fathers and mothers remains scarce and shares some limitations that need to be addressed in future research. Only a few studies were found, each with its own limitations. The studies had different objectives and the methodologies used were much diverse. Also, most studies focused on emotional and behavioural outcomes such as internalizing/externalizing and depressive symptoms, rather than outcomes related to adaptive development. Further, only one of the studies analyzed the consistency between ESPP of mothers and fathers, which is basic to the understanding of parental ESPP and its effects in a more holistic manner. Some methodological limitations can also be mentioned. None of the studies presented sample size estimations and some may have lacked the power to detect significant associations. Moreover, though most studies included reliable measures, some did not present internal consistency indicators for some measures. Additionally, despite the importance of the cultural context on emotion socialization, the studies found were no exception to the limited cross-cultural research on this topic, pertaining to the majority of the investigation into USA.

In future, more studies are needed to increase knowledge about the complementary role of the mother and father on the emotion socialization of their adolescent child. Also studies that deepen the differences between the practices of the father and the mother regarding their children, depending on whether they are boys or girls, are necessary. We underline the importance of exploring the parents-child co-regulation of emotions, which is referred to but not explored in most studies, as these studies focus on parents’ effects rather than on the effects of adolescent behavior and characteristics.