Stereotypes

Stereotypes are shared beliefs (Karasawa et al., 2007; McGarty et al., 2009) about the characteristics, attributes and behaviours of members of certain social groups. They are cognitively processed and often occur without conscious awareness (Devine, 1989). Stereotypes are not necessarily negative although they may have more negative connotations regarding the outgroup in relation to the ingroup (Hilton & Hippel, 1996). They contain information about the social roles of each group (e.g., Eagly & Steffen, 1984; Koenig & Eagly, 2014), their social status (Jost & Banaji, 1994), and the power relations between different groups (Pratto et al., 2006). They influence emotional reactions to members of different groups and, consequently, their behaviour (Cuddy et al., 2007; Fiske et al., 2002).

Extensive evidence has shown that stereotypes serve many purposes, both cognitive and social. Cognitively, they help to make sense of the huge set of information that comes to the individual, simplifying their needs (Bodenhausen, 1990), making information processing easier. Information is categorized more easily, identified and remembered (Bodenhausen, 1990), reducing the effort and energy required for other tasks. They are, therefore, cognitive shortcuts that allow the individual to give meaning to their social context (Tajfel, 1974).

Due to collective sharing beliefs, inherent to their nature, stereotypes are not only products of intra-individual processes (e.g., information processing), they are phenomena that also occur at the intergroup level and serve to differentiate different groups (Tajfel, 1974), classifying, for example, the ingroup more positively than the outgroup. They also serve to explain certain social events (McGarty et al., 2009) and serve to justify the behaviour of members of different groups (Tajfel, 1974), for example discriminatory behaviours. In fact, stereotypes can not only promote discrimination by influencing perception but also reinforce and justify disparities between groups.

The Stereotype Content Model (SCM; Fiske et al., 2002) proposes two fundamental dimensions of stereotypes: warmth (associated with cooperative groups and denied to competitive groups) and competence (associated to high-status groups and denied to low-status groups). This model argued that we rarely stereotype a group only through negative or positive stereotypes. The content of stereotypes is, in most cases, ambivalent, that is, considering a group favourably in one dimension and unfavourably in the other. This ambivalence stems from the power relations between the ingroup and the outgroup. In a study, Cuddy and collegues (2009) asked European participants to characterized their and other European countries. High-status northern groups were characterized as competent but lack in warmth, cold and distant in opposition to lower-status southern groups, viewed as warmth and friendly but incompetent peoples as the Portuguese, Italians, or Greeks. In an international study, Durante and collegues (2013), investigated stereotype ambivalence and income. Portugal, the most unequal country in Europe (according to the GINI’s coefficient) reported ambivalence in terms of group’s competition-warmth correlation, but not warmth-competence, and status-competence correlations.

Since the classic study by Katz and Braly (1933), much has been investigated about the content of the stereotypes of different social groups. In Portugal, several studies pre-tested material to be used in subsequent research. For example, a study from Cabecinhas and Amâncio (2004) characterizes the stereotype content of Angolans and Portuguese living in Portugal and they found that the greatest differentiation between the two groups was: positive sociability, expressiveness, exoticism, and negative instrumentality for Angolans; negative sociability, conservatism, dominance, and positive instrumentality for the Portuguese, confirming previous research about socially asymmetric groups. A research from Brazão and Garcia-Marques (2004), shows stereotypical and non-stereotypical negative atributes regarding Skinheads. Additionally, a study of Garrido et al. (2009), identifies the stereotypical traits that best differentiate Homossexuals from Heterossexuals, and Arabs from Americans. Marques, Lima, and Novo’s study (2006), allows to distinguish the stereotypical traits associated to Young and Old people in Portugal. A different study from Moreira et al. (2008) assesses the cultural stereotypical attributes of 32 professional groups in Portugal.

Regarding behavioural descriptions of different personality traits, Garrido et al. (2004) tested 201 behavioural descriptions related to four traits: adventurous, religious, ecological, and artistic. In the same line of research, Jerónimo et al. (2004) analysed corresponding and non-corresponding personality traits generated for 96 behaviours, with 24 behaviours illustrative of four traits each: Kind, Unkind, Intelligent, and Stupid. Another study from Garrido (2013) tested 201 behavioural descriptions illustrative of two personality traits: Kindness and Intelligence. Differently, some researchers are interested in ambiguous behaviour that could be characteristic of one or more personality traits. For example, Ramos and Garcia-Marques (2006), created 163 behaviour descriptions that elicit simultaneously two personality traits.

Intergroup emotions

Stereotypes can affect the appraisal of specific emotions (Bijlstra et al., 2014; Inzlicht et al., 2008). Indeed, much more than an individual phenomenon, emotions are also intergroup phenomena in that they refer to specific emotions that individuals feel towards a social group or its members (Smith & Mackie, 2015). Fundamentally, intergroup emotions arise from the distinction that individuals tend to make between their group and the group of others (Tajfel, 1974). That is, to feel a particular emotion towards one group, one has to see oneself as an integral part of the group and see others as integral parts of other groups. Emotions are then shaped by how groups view the world, and over time and repetition become part of the group itself (Mackie et al., 2008). They are also shaped by subjective assessments of the relationship between the two groups, for example, if an individual believes that a group of migrants competes with their group for employment, they may be angry or jealous of members of that group (Mackie et al., 2000, 2008; Smith & MacKie, 2008). The SCM, postulates that people can experience four emotions directed to different groups depending the group’s stereotypical warmth and competence. For example, warm and competent groups, such middle-class Americans, elicit emotions of pride. Groups seen as competent but not warm, such as Jews, elicit envy. Warm and incompetent groups, such the elderly, elicit pity. Cold and incompetent groups, such the welfare recipients, elicit contempt. Another model from Cottrell and Neuberg (2005) take a sociofunctional approach that emphasizes the variety of potential intergroup threats that may elicit distinct emotional reactions. For example, an outgroup may threaten an ingroup with diseases or group values evoking disgust. Importantly, intergroup emotions play an important role in the interaction between individuals belonging to different groups, that is, different emotions can trigger different behaviours (Mackie et al., 2000, 2008). For example, feeling angry about members of a particular group can be an incentive for the individual to behave aggressively toward members of a group, while feeling admiration for members of a particular group can stimulate mutually beneficial behaviours (Cuddy et al., 2007).

Study

Aim

Despite the different studies referred above, there is a lack of scientific evidence and a scarce number of validated studies in Portugal considering simultaneously: stereotypic traits, intergroup emotions and behavioural tendencies of social groups. Moreover, to our knowledge, there are no studies in Portugal that take into account most of the 12 groups that we considered. The aim of this study is to fill this gap.

Participants and procedure

Ninety-eight participants recruited online via social media, separated into three samples, completed our questionnaire. The questionnaire is the same for all samples but varies according to the social groups evaluated. We decided to split the questionnaire into three versions in order to prevent participant fatigue (e.g., one questionnaire would be very long and exhausting to fill in), and to avoid random answers. All participants were reassured of the anonymity of their identity and their answers. Each participant provided his/her written informed consent before the study began. An email address was made available for possible future questions.

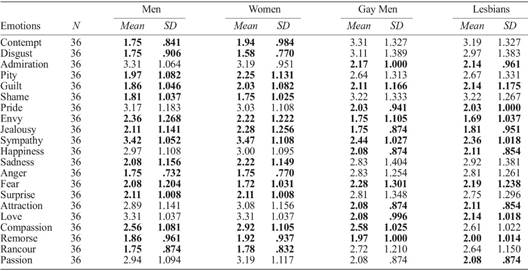

In the first sample, 36 participants (13 men, 23 women, M age=47.97) answered the questionnaire related to four social groups: Men, Women, Gay Men (“Homossexuais Masculinos” in Portuguese) and Lesbians. All participants were White, one participant was Bisexual, and one male participant indicated that was gay.

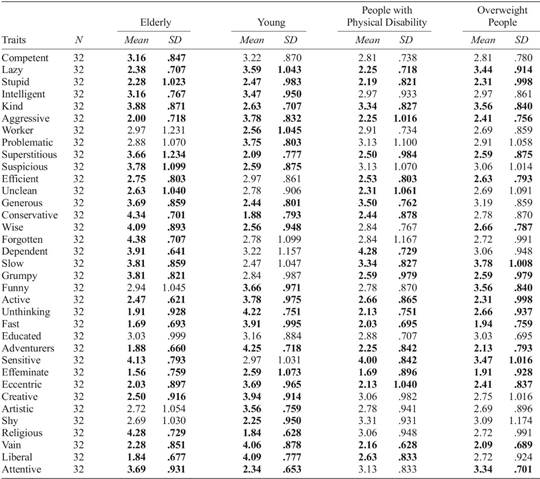

In the second sample, 32 participants (10 men, 22 women, M age=49.91) answered the questionnaire related to four social groups: Elderly, Young, People with Physical Disability and Overweight people (“Obesos” in Portuguese). Thirty-one participants were White, and two participants were physically disabled.

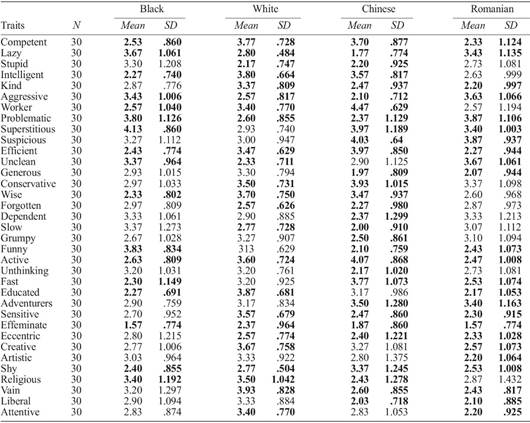

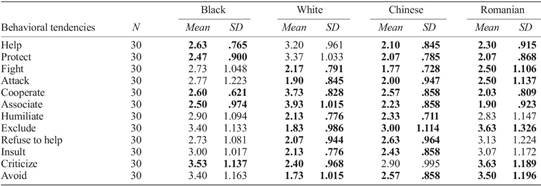

In the third sample, 36 participants (14 men, 26 women, M age=48.70) answered the questionnaire related to four social groups: Black, White, Chinese and Romanian. All participants were White, 28 participants were Portuguese, one participant was Italian, and one participant was Moldovan.

Sensitivity analysis, with α=.08, 1-β=.91/93, N=32/36, and Cohen’s f=.115 suggested that a sample size of 32/36 participants had enough power to detect a small effect size (Cohen, 1988).

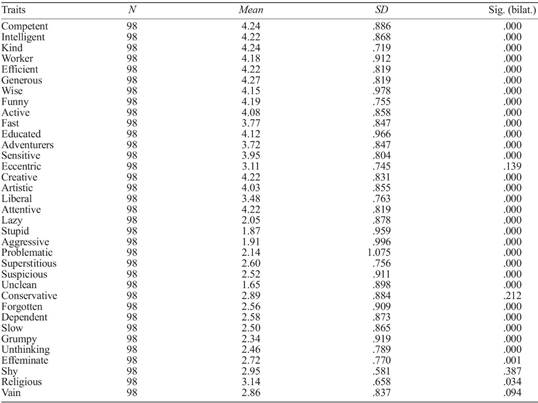

Scale

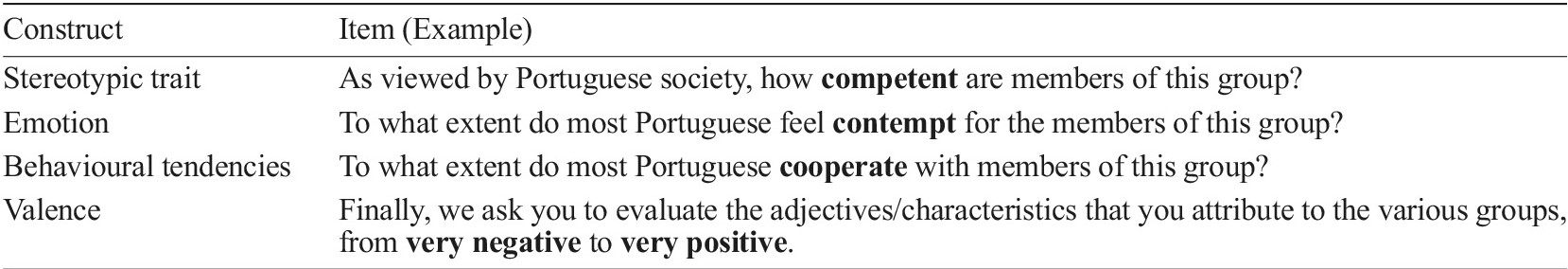

The scale was developed based on previous investigations of SCM (Fiske et al., 2002) and on stereotypes, emotions and behavioural tendencies in Portugal (Brazão & Garcia-Marques, 2004; Garrido, 2013; Garrido et al., 2004, 2009; Jerónimo et al., 2004; Ramos & Garcia-Marques, 2006) and on the classic study by Katz and Braly (1933). Using a five-point Likert scale (from 1=not at all to 5=extremely), participants evaluated 12 Portuguese social groups related to 35 stereotypic traits, 21 emotions, 12 behavioural tendencies, and rated the valence from the 35 stereotypic traits (from -2=very negative to +2=very positive), selected according to previous investigations. At the end, we asked participants to answer sociodemographic questions, a question about sexual orientation, and a question about physical disability (see Table 1). All participants were instructed to answer according to the way these groups are seen in the Portuguese society.

All scales have good internal consistency with Conbrach α≥.90.

Results

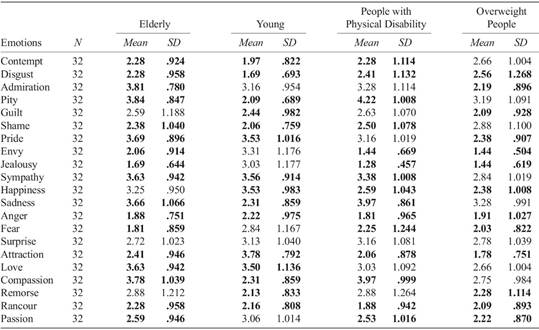

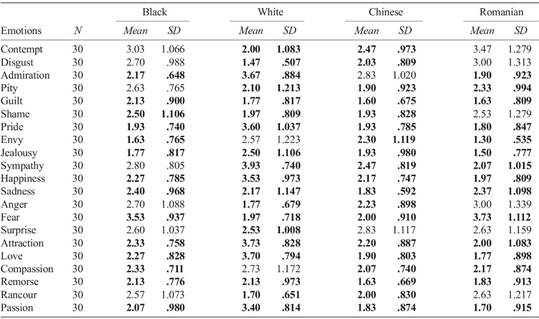

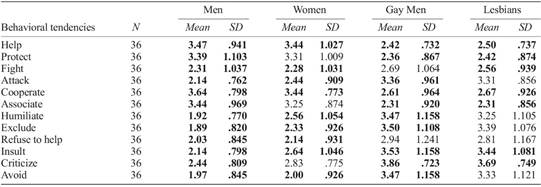

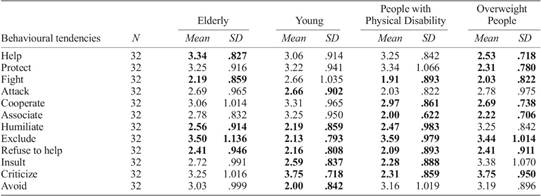

In order to assess the degree of stereotypicality of each trait, mean, standard deviation and respective 95% confidence interval for each trait were calculated. A statistical t-test was also performed to test if the mean response to the traits was equal to 3 - null hypothesis - or different from 3 (see Appendix 1, 2 and 3). The same procedure was performed to test emotions (see Appendix 4, 5 and 6) and behavioural tendencies (see Appendix 7, 8 and 9) toward 12 social groups. The results of the test show typical traits, typical emotions and typical behavior tendencies with values above score 3 of the Likert scale, and with statistical significance. Traits with values below the mean and with statistical significance are atypical. Concerning emotions also with values below the mean and with statistical significance our reasoning is that participants did not considered that Portuguese feel those emotions for that particular groups. We applied the same reasoning for behavioural tendencies, that is, we considered that values below the mean and with statistical significance suggest that people do not behave that way toward these groups. Mean values with statistical significance (p≤=0.05) are highlighted in bold in all tables.

Our results shows that Men are seen as competent, intelligent, workers, efficient, actives, adventurers, and conservative; Women are seen as competent, kind, worker, superstitious, generous, conservative, wise, dependent, grumpy, funny, active, educated, sensitive, effeminate, religious, vain, and attentive; Gay Men are seen as stupid, aggressive, sensitive, effeminate, eccentric, creative, religious, vain, and liberal; Lesbians are seen as suspicious, active, sensitive, eccentric, creative, and liberal; Elderly are seen as competent, intelligent, kind, superstitious, suspicious, generous, conservative, wise, forgotten, dependent, slow, grumpy, sensitive, attentive, and religious; Young people are seen as lazy, intelligent, aggressive, problematic, funny, active, unthinking, fast, adventurers, eccentric, creative, artistic, vain, and liberal; People with Physical Disability are seen as kind, generous, dependent, slow, and sensitive; Overweight People are seen as lazy, kind, slow, funny, sensitive, and attentive; Black people are seen as lazy, aggressive, problematic, superstitious, unclean, funny, and religious; White people are seen as competent, intelligent, kind, worker, efficient, conservative, wise, active, educated, sensitive, creative, religious, vain, and attentive; Chinese people are seen as competent, intelligent, worker, superstitious, suspicious, efficient, conservative, wise, active, fast, adventurers, and shy; Romanian people are seen as lazy, aggressive, problematic, superstitious, suspicious, unclean, and adventurers (see Appendix 1, 2, and 3).

In regard to intergroup emotions, Portuguese people feels sympathy towards Men’s group and Women’s group; feels admiration, pity, pride, sympathy, sadness, love, and compassion towards Elderly’s group; feels pride, sympathy, happiness, attraction, and love towards Young’s group; feels pity, sympathy, sadness, and compassion People with Physical Disability’s group; feels fear towards Black’s group; feels admiration, pride, sympathy, happiness, attraction, love, and passion towards White’s group; feels fear towards Romanian’s group. For Gay Men, Lesbians, Overweight People and Chinese we could not find any statistically significant result related to intergroup emotions (see Appendix 4, 5, and 6) above the middle point of the scale. However, below the middle point of the scale, we could find disgust, guilt, pride, envy, jealousy, sympathy, happiness, and fear for Gay Men; admiration, guilt, pride, envy, jealousy, sympathy, happiness, and fear for Lesbians; disgust, admiration, guilt, pride, envy, jealousy, happiness, anger, fear, attraction, remorse, rancour, and passion for Overweight people; contempt, disgust, pity, guilt, shame, pride, envy, jealousy, sympathy, happiness, sadness, anger, fear, attraction, love, compassion, remorse, rancour, and passion for Chinese.

Concerning behaviour tendencies, we found that the Portuguese people tend to help, protect, cooperate, and associate with Men’ group; Help, and cooperate with Women’ group; attack, humiliate, exclude, insult, criticize, and avoid Gay Men’ group; insult, and criticize Lesbian’ group; help, and exclude Elderly’ group; criticize Young’ group; exclude People with Physical Disability’ group; exclude, and criticize Overweight People’ group; criticize Black’ group; cooperate, and associate with White’ group; exclude Chinese’ group; and exclude, criticize, and avoid Romanian’ group (see Appendix 7, 8, and 9).

Regarding valence, an ANOVA analysis of variance was performed to test whether valence is affected by the subsample factor. From the results, it was concluded that there is no influence from this factor with values ranging from Competent F(2,97)=0.040, p=.960, η 2 =.056 to Sensitive F(2,97)=2.189, p=.118, η 2 =.437). The “Eccentric” trait is the one exception where there is at least one significant difference in a pair of subsamples F(2,97)=6.013, p=.003, η 2 =.873. We understand that this exception is due to the ambiguity that this feature seems to demonstrate. For this reason, and because no other characteristics are influenced by the “subsample” factor, we present the values of the three subsamples together. Results can be seen in Appendix 10.

Discussion

As mentioned earlier, we found some pre-tested material (e.g., stereotypical traits) relating to some social groups in Portugal, such as Elderly and Young people, Homosexuals and Heterosexuals males, Skinheads, and Young Angolans and Young Portuguese. But, as far as we know, there is a lack of pre-tested material for the other social groups. It is also noteworthy that the continuous social changes may bring some variation in the meaning and importance of each of the traits (Garrido et al., 2009) attributed to each social group, and although they have been previously studied in Portugal, we chose to study them again, as well as the valence attributed to each trait. Therefore, our results corroborate previous findings, but diverge in some groups: elderly are seen as competent, intelligent and kind. These three positive traits do not appear in previous literature. We could hypothesize there was a bias due to the characteristics of the sample, but only three participants were above 65 years old. For Young people, we found different negative traits, like lazy, unthinking, vain, aggressive, and problematic. Related to Gay Men, we found three different negative traits like stupid, aggressive, and vain. So, we can put forward that here may have been a change in the perception of these groups. However, White people remains the group with the most positive attributes in line with previous findings (Fiske et al., 2002).

As well as stereotypes, intergroup emotions can be predictors for intergroup behaviour (Cuddy et al., 2007; Vala et al., 2015). White, Young, and Elderly people were the groups with more positive emotions attributed. In fact, and in line with previous studies, people feel both pity and admiration toward the elderly and, at the same time they express helping intentions towards them, they report that they could as well exclude people from this group. Admiration was the only emotion attributed to Men as a group, however this group was the one associated with more positive behaviour tendencies in general (i.e., hep, protect, cooperate, and associate) and not the White’s group as expected from previous studies. Indeed, White people are admired and loved but it seems that they no need protection or help, instead one wants to cooperate and associate with them. Black and Romanian people are feared and possibly that is why they are excluded, and Romanians are also criticized and avoided. Gay Men’s group were the most discriminated group (i.e., associated with avoidance exclusion) although we found no specific emotions related to that group. On other hand, Lesbians are not so discriminated as Gay Men although the ratings related to emotions are quite similar and almost overlapping. Overweight people and People with Physical Disability are excluded but the former is also criticized, probably, because they are perceived as responsible for their excess weight. Finally, people feel sympathy for Women, and they tend to help them. Helping is not always a positive behaviour, could derive from pity and sympathy, like helping an old woman to cross the street. Nevertheless, people cooperate with them, which is a positive behaviour.