Introduction

Economics and financial experts stated that 2007 was marked by one of the most drastic financial crises on a global level, regarded as the worst within the financial markets since the 1930’s. This period was known as the subprime crisis and started with the American mortgage system causing the bankruptcy of several banks, strongly affecting financial markets at a national and international level. In 2008/2009, the crisis expanded rapidly across Europe, and its economic consequences, as well as its impact on individuals’ health and well-being, are being felt to this day (Greenglass et al., 2014). This crisis evolved from the financial sector to the real economy, affecting individuals in their daily lives through increased unemployment, family indebtedness, increased household costs, decreased wages and public investment (e.g., in health, education, and social systems), and it had an impact on people’s health (Jesus et al., 2016; Keegan et al., 2013; Marjanovic et al., 2013). Among the many symptoms of the financial crisis, the cutoff in public expenditures and social investments caused the loss of 67 million jobs, and in countries such as Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain, young adults were severely affected by youth unemployment (Dekker et al., 2014).

Studies by Cooper (2012); Catalano et al. (2011); Frank et al. (2013); Greenglass et al. (2013); Althouse et al. (2014); Jesus et al. (2016) confirm the negative relationship between financial threat and life satisfaction and that a decreased perception of psychological health affects general well-being. Some examples of this negative relationship are: (a) feelings of helplessness (e.g., psychological distress); (b) depression; (c) anxiety; (d) suicidal ideation; (f) physical and health problems, such as increased arterial diastolic and systolic levels; (g) myocardial infarction, among others. Thusly, we can infer that times of financial threat generate feelings of fear, insecurity and anguish related to personal finances, causing a diminished perception of life satisfaction and individuals to have a more fragile psychological and physical health, also affecting their life satisfaction.

The increase of these symptoms occurs once subjects recognize that they have no control whatsoever on the events that surround them (e.g., increased unemployment rates). This situation negatively affects life satisfaction: individuals start to change their behaviors, habits, and priorities, for example, on clothing purchase, food habits, transportation, social life, education, and health (Fiksenbaum et al., 2017).

From a different perspective, some authors have also shown that periods characterized by financial difficulties increase the number of arguments between couples (Frade & Coelho, 2015; Thorne, 2010) and domestic violence cases (Schneider et al., 2016). Money-related problems are the ones that cause a greater disagreement, and not only do they lead to emotional suffering, but they also contribute to the onset of symptoms, such as stress, anxiety, and depression. The aforementioned authors argued, as well, that debt levels are positively associated with levels of anxiety, followed by the moral sense of shame and failure. This increases psychological suffering and, based on these examples, we can infer that life satisfaction decreases.

Research proposal: Financial threat mediated by coping

Through the analysis of the aspects that characterize a financial crisis, we argue that it is important to think about research models that assess proactive coping strategies that will contribute to reduce the negative effects of financial threat measures on individual well-being and life satisfaction. According to Pais-Ribeiro and Rodrigues (2004), the human development process requires multiple challenges, changes and reorganization. The authors also infer that cognitive coping strategies will help the subject to ensure the balance between intrinsic and extrinsic processes.

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) define proactive coping (problem focused) as a means in which individuals seek to anticipate solutions to the problems by creating alternative solutions (acting actively), inferring that it can be considered adaptive (e.g., when the conditions for change are assessed as susceptible). For Lazarus and Folkman (1984), proactive coping is activated by the subject when there is a confrontation with stressful moments (e.g., when a negative event arises, it activates, in order to decrease the perception of the intensity of stress, to prevent and/or decrease the appearance of physical and psychological malaise). According to the authors, when our proactive coping is active, an intrinsic force emerges within us, increasing our internal abilities to face difficult periods. Therefore, the intensity of the stressor decreases (and individual resources improve), in order to protect individuals’ mental health.

Several studies support that proactive coping acts as a mediator, reducing the effects of economic stressors on psychological health indicators (Chen et al., 2012; Jesus et al., 2016; Stein et al., 2013). Coping is then like a buffer for stressful events. Greenglass (2002) proposed that coping has a proactive nature, characterized by the anticipation of a stressful moment. The key point of Greenglass’s (2002) proposal is the orientation for future events. The author stated that this strategy can contribute to increase psychological well-being, as the individual experiences a cognitive transformation and mobilization of thought. This will also contribute to the ability of anticipating stressful moments, thus creating new paths for solving problems.

Further studies carried out by Greenglass and Fiksenbaum (2009) corroborate the aforementioned propositions. The results of their research infer that the use of proactive coping strategies (e.g., problem focused, orientated for future events) is closely related to the capacity that individuals have to control and anticipate solutions caused by the stressful event, reducing its impact on psychological health and, consequently, on life satisfaction. Still, according to Greenglass and Fiksenbaum (2009), proactive coping contributes to a better psychological health and general well-being, being in line with the present study, where we propose to understand how proactive coping can mediate the negative symptoms of financial threat towards a better perception of life satisfaction.

Authors like Blalock and Joiner (2000) suggested that proactive coping can be used as a mediator between stressful life events, leading the subject to an adequate solution to a problem. Wadsworth and Compas (2002) proposed that in moments of financial threat this strategy can promote resilience, in other words, the subject modifies a set of conscious and voluntary efforts that regulate emotions, cognitions and behaviors (on a given environment), which will allow the modification of responses to specific stressful events or circumstances (Compas et al., 2001).

The literature highlights that proactive coping can transform moments of adversity and increase not only a subject’s inner strength to react positively and adaptively, but also individual growth in moments of suffering, trauma or stress, namely, when we anticipate problems (Aldwin, 1994; Linley & Joseph, 2004). Seligman (2000) proposed that proactive coping strategies were linked to positive psychology and referred the growth paradox, e.g., when facing a negative moment, an individual may find positive ways to deal with such events, whether they are difficult, adverse or potentially traumatic, to subsequently be empowered and improve life satisfaction.

Therefore, coping and its adaptive features, constructive and functional, will be used as a way to decrease the impact of financial threat on life satisfaction, as well as in the understanding of mechanisms that could strengthen subjects in times of stress, anguish, and fear. In this study we will employ proactive coping strategies in order to mitigate the impact of financial threat on life satisfaction. Moreover, we will analyze proactive coping in two different situations: (1) independently from the level of financial threat and (2) within the group of individuals who express higher levels versus lower levels of financial threat.

Bearing in mind the reviewed literature, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1) - Financial threat is negatively and directly associated with life satisfaction; Hypothesis 2 (H2) - Multiple-group analysis of coping mediates the association between financial threat and life satisfaction.

Method

Participants

A total of 901 adults participated in this study. The subjects responded to a research protocol composed of pre-established instruments to assess financial threat, life satisfaction and proactive coping. The sample’s mean age was approximately 37 years old (SD=12.86). 33.1% of the participants were males (n=295) and 66.9% were females (n=603). Regarding the sample’s marital status, 52.1% of the participants were married and/or living in a non-marital relationship (n=466) and 47.9% lived alone due to being separated, divorced, single, and/or being a widower/widow (n=435).

Measures

The measures used in this study were composed by the following self-report questionnaires:

Financial Threat Scale (FTS), developed by Lee-Baggley et al. (2004). According to Marjanovic and colleagues (2013), FTS assesses feelings of uncertainty and perceived threat in relation to an individual’s financial situation. This scale was composed of five items (e.g., How uncertain do you feel?) with a five-point Likert scale (1=Not at all; 5=Extremely uncertain). Studies carried out by Jesus et al. (2016); Marjanovic et al. (2013); Viseu et al. (2019) demonstrated that this measure has adequate psychometric properties, namely in terms of reliability and validity.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS-5), developed by Diener et al. (1985), assesses an individual’s life satisfaction and comprises five questions (e.g., I am pleased with my life.) on a five-point Likert scale (1=Strongly Agree; 5=Strongly Disagree). The results of this scale vary between five and 25.

The Pro-Active Coping Scale (PACS), developed by Greenglass et al. (1999) refers to the coping strategies adopted by individuals when facing stressful situations. This scale presented 14 items (e.g., After attaining a goal, I look for another, more challenging one.) organized on a four-point scale (1=Not at all true; 4=Completely true). In our study, we only considered items with a Loading value greater than 0.5, thusly leaving us with 9 items.

Procedure

This study was conducted between November 2015 and May 2016.

The recruitment of participants was performed through a contact database created from previous researches conducted at a Portuguese Research Centre, meaning that our participants were part of a convenience sample. An email was sent to the respondents with a direct link for answering the questionnaire and with an explanation of the objectives of our study. The only participation criterion was related to age, the participants had to be over 18 years old.

The participants were asked to answer a research protocol composed of established instruments that evaluated the perception of financial threat, life satisfaction and proactive coping. Participants were also asked to read an informed consent statement guaranteeing the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses. It was established between the parties that there would be no compensation of any kind or any incentives for participating in this research. The participants were asked, as well, to answer a socio-demographic questionnaire.

Data analysis

We used AMOS 21.0 (software) with the maximum likelihood estimation method. Subsequently, we examined the structural model in order to test H1. In a second moment (H2), multiple-group analyses were implemented to assess the mediating effect of coping on the relationship between financial threat and life satisfaction. In these analyses, we considered three situations: (1) model with all the participants in the study (n=901); (2) model with a financial threat score higher than the average (n=434); and (3) model with a financial threat score equal or below the average (n=467). For this model, the items with a Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CI-TC) lower than .03 were excluded from the data analysis, since they revealed a weak correlation with the selected constructs (Marôco, 2014).

Results

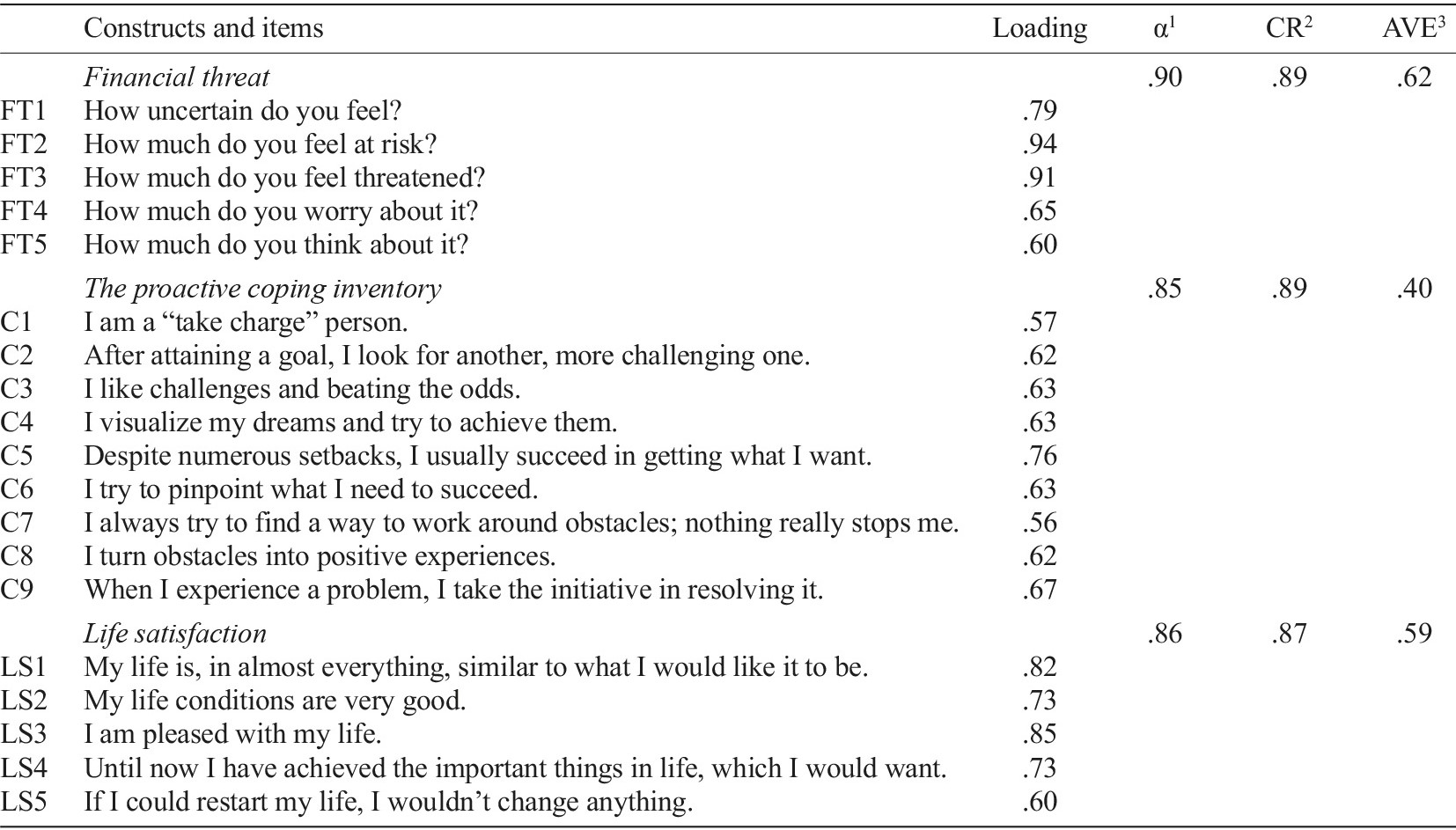

Our measurement model reported an adequate reliability and validity (Table 1). Individual reliability was confirmed through the analysis of the standardized factor loadings of the three constructs, values above .50 and statistically significant at the .01 level were observed (Anderson & Gerbing, 1982). Reliability was tested by observing the Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability (CR) coefficients. All (CRs) were higher than .70 and the Cronbach’s Alpha were higher than .80 (Financial threat: α=.90 and CR=.89; Coping: α=.75 and CR=.86; Life satisfaction: α=.86 and CR=.86) (Kline, 1998).

Table 1 Results for the measurement model

Note. 1Cronbach’s alpha; 2Composite reliability; 3Average variance extracted. Source: Author.

Regarding the convergent validity of each construct, an average variance extracted (AVE) of at least equal to .50 is required (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). However, since its loadings were higher than .56 and deleting those with lower loadings did not increase significantly the AVE, we opted for not deleting additional items. According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), discriminant validity was evaluated by comparing the AVE of each factor with the squared correlation between the pairs of constructs. Results showed that there was discriminant validity, since the squared root of each factor’s AVE was higher than those correlations.

Testing Hypothesis 1 involving constructs’ relationships

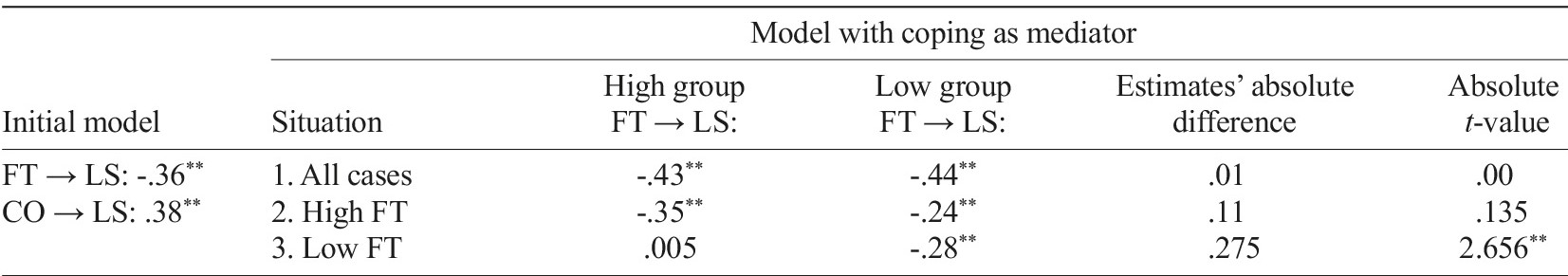

Table 2 presents the standardized path estimates between the hypotheses. H1 stated that financial threat was negatively and directly associated with life satisfaction. The higher the financial threat, the lower the perception one has on his/her life satisfaction. Regarding this hypothesis, the results showed a direct and negative association between financial threat and life satisfaction (β 1=-.36, p=.000), meaning that it was supported. This hypothesis was also validated, showing that the higher the subject’s proactive coping, the higher the perception of life satisfaction. The estimated coefficient was positive and statistically significant (β 2=.38, p=.000).

Mediating effect of coping and multiple-group analysis

Table 2 also presents the results for the analysis of the role of coping on the relationship between financial threat and life satisfaction. Given H2, multiple-group analysis of coping might mediate the association between financial threat and life satisfaction. To test this interaction, we implemented a multiple-group analysis within the SEM procedure. Prior to implementing this procedure, we obtained the score of each individual in the coping scale. Then, the mean of this score was computed and the individuals were classified in one of two groups based on their coping levels (low versus high). Participants whose coping levels were lower or equal than the average were included in the first group, low coping (n=494), and participants who presented an average score higher than the average were classified in the second group, high coping (n=407). According to H2, it is expected that the negative association between financial threat and life satisfaction is significantly weaker within those individuals with high coping levels and stronger within those with lower coping values. By applying a multiple-group analysis, a model with path estimates that are different between groups is compared with another one that assumes that all parameters (factor loadings and path estimates) are constrained to be equal (Marôco, 2014). In a first moment, the model’s invariance, which means differences between groups, is tested using the Δχ 2 statistics that, under the null hypothesis, states that the parameters are equal across groups. Under this condition, coping has a significant mediating effect whenever Δχ 2 reports p<.05.

The results for H2 are presented in different situations (Table 2).

Table 2 Path estimates in the initial model and in the models with coping as mediator

Note. FT: Financial threat, CO: Coping, LS: Life satisfaction; *p<.05, **p<.01. Source: Author.

Firstly, considering all participants in the study (n=901). In this case, the Δχ 2 statistics rejects invariance both in the measurement model (Δχ 2 =14.81; p=.06) and structural model (Δχ 2 =.92; p=.34). This means that the model is not statistically different between individuals with low and high coping levels. Table 2 shows that, in the two groups, the relationship between financial threat and life satisfaction is negative and statistically significant. It also shows that the path estimate is slightly weaker in the higher coping group (β=-.43 in comparison to β=-.44 in the lower coping group). So, the effect of the financial crisis on life satisfaction was marginally reduced in the group that showed higher levels of coping. However, and in accordance with our results regarding the Δχ 2 test, the pairwise parameter comparisons test showed that the difference between the path estimates, with a magnitude of .01, was not statistically significant (|t|=.00; p>.01), meaning that the mediating role of coping was not significant. The model with invariant measurement and structural weights reported a goof fit: χ 2 /df=2.45<5; RMR=.05<.08; RMSEA=.04<.05; GFI=.97; AGFI=.94; NFI=.97; IFI=.98; TLI=.98; CFI=.98; all>.95.

In a second situation, H2 was evaluated in the group of participants with a financial threat score higher than the average (n=434). From these, 180 reported a high coping level and 254 reported a low coping level. In this multiple-group analysis, the results indicated that the model had unequal measurement weights (Δχ 2 =28.33; p=.000). Under this unrestricted model, the results of the pairwise parameter comparisons test showed that the difference in the path estimates between the two groups, of .11, was not statistically different (|t|=.135; p>.01) (Table 2). So, in this situation, the mediating role of coping was also not significant. The unrestricted model used in this analysis also reported a goof fit, however worse than in the previous situation: χ 2 /df=2.25<5; RMR=.06<.08; GFI=.95; AGFI=.90; NFI=.93; IFI=.96; TLI=.93; CFI=.96; all≥.90.

Afterwards, H2 was tested in the group of participants with a score of financial threat equal or lower than the average (n=467). From these, 227 individuals reported a high coping level and 240 reported a low coping level. The Δχ 2 statistics indicated invariance in the measurement model (Δχ 2 =13.03; p=.11) but rejected that the structural model had the same path coefficient in the two groups (Δχ 2 =7.17; p=.007). This means that the model had the same measurement weights in the two groups, but a statistically different path estimate between individuals with low and high coping levels. The mediating role of coping was quite relevant in this situation. As reported in Table 2, the relationship between financial threat and life satisfaction was negative and statistically significant in the low coping group (β=-.28; p<.01). However, in the high coping group the path estimate was close to zero and was not significant (β=.004; p=.95). Therefore, the impact of the financial crisis on life satisfaction is significantly reduced and almost disappears in the group showing higher levels of coping. In this case and as expected, given the results from the Δχ 2 test, the absolute difference between the path estimates (of .275) was statistically significant (|t|=2.66; p<.01).

The model with invariant measurement weights and different structural weights also presented a goof fit: χ 2 /df=1.42<5; RMR=.04<.08; RMSEA=.03<.05; GFI=.96; AGFI=.94; NFI=.95; IFI=.99; TLI=0.98; CFI=.99; all>.95.

Discussion

Bearing in mind that Portugal was strongly affected by the financial crisis, this study explored the association between financial threat and life satisfaction, as this economic stressor negatively affects the psychological health of individuals and increases symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression (Chen et al., 2012; Leal et al., 2014; Marjanovic et al., 2013). Essentially, what we were looking for with this study was to assess proactive coping strategies that mitigated the negative effect of financial threat on life satisfaction. To that end, we used proactive coping as a mediating variable of this relationship. The obtained results allowed us to draw some conclusions.

Compas et al. (1991) suggested that adaptive coping acts as a promoter of resilience in times of economic difficulties and financial threat. Fundamentally, our goal was to understand how some positive psychology mechanisms, namely proactive coping, could mediate this relationship and mitigate the negative impact of financial threat on life satisfaction. Our results showed that there was a negative and direct relationship between financial threat and life satisfaction, meeting the aforementioned literature. On the other hand, there was a positive and direct relationship between coping and life satisfaction, showing that proactive coping may help individuals in a process of behavioral adaptation to a particular situation, even if is stressful or difficult. According to the results, our first research hypothesis was confirmed: H1 predicted a negative and direct association between financial threat and life satisfaction, in other words, individuals with higher financial threat perceptions are more prone to experience a decreased life satisfaction.

To test the main premise of this study, established in H2, the sample was divided into two groups, based on the individuals’ coping levels. After analyzing the results, we observed that the negative feelings of financial threat on life satisfaction were mitigated in the group that showed higher levels of coping. However, this reduction was only significant in the subsample with a low to moderate level of financial threat. These results met with what we aimed to analyze: in some circumstances, coping can act as a mediator of the effect of financial threat on life satisfaction, decreasing its negative impact. Therefore, we have to consider that coping is a multidimensional process and that it depends on individual and environmental conditions (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000). Authors like Folkman and Moskowitz (2000) argued that an individual cognitively reappraises negative events, in order to capitalize on the best way to obtain positive benefits from those events. Wadsworth and Compas (2002) suggested that adaptive coping promotes resilience during periods of economic hardships, since there is an ensemble of conscious efforts to regulate an individual’s emotions. In 2009, Seligman and colleagues referred to this behavior as the paradox of behavioural learning: to see something positive in a negative event.

With these results in mind, we will be able to focus our knowledge in favour of practices aimed at promoting well-being and reducing negative symptoms like fear, stress, anxiety, and insecurity about personal finances. It should be also noted that there is a lack of literature that addresses the relationship between financial threat and life satisfaction. However, this study took a step forward, not only by assessing the direct relationship between those two variables, but also by considering the mediating role of coping.

We can infer that periods of financial threat have a negative impact on individuals’ psychological health, directly and negatively influencing life satisfaction. Additionally, we can ascertain that coping strategies can mitigate this relationship, by lessening the aforementioned negative impact. As such, coping strategies act as a barrier, preventing financial threat’s impacts on the evaluation that individuals perform about their lives. In individuals with low perceptions of financial threat, coping practically dissolved the effect of the financial threat.

The results of our study are in agreement with the assertions of other authors, such as Pais-Ribeiro and Rodrigues (2004). The authors stated that the human development process requires multiple challenges, changes and cognitive restructuring, and that coping strategies help an individual to ensure the balance between intrinsic and extrinsic processes. Alternatively, according to Lazarus (1999), proactive coping is activated by the subject. Therefore, when there is a confrontation between specific moments of stress, an intrinsic strength emerges from within and increases the skills that the subject possesses to face periods of difficulty. Hence, the intensity of the stressor decreases, promoting the prevention of pathological symptoms. Recently, Fiksenbaum and colleagues (2017) analyzed individuals’ perceptions of financial threat and how those perceptions relate with life satisfaction. Their study was performed with a Canadian and Portuguese sample. The authors observed that stress, anxiety and suicidal ideation levels increased in subjects that had a higher perception of financial threat.

In sum, and after observing the consequences of periods of financial threat, we can affirm that the conclusions of this study have theoretical and practical implications, mainly for the development of intervention programs based on the strengthening of proactive coping and positive emotions, such as optimism and social support, which will help individuals during periods of financial threat.

Limitations and future studies

Sampling

One of the limitations of our study was related with the sampling process. The collected sample should have been larger and more diversified, by comprising the various regions of the country and taking into consideration the socio-economic conditions and literary skills of the participants. On the other hand, a longitudinal study could have been performed to examine possible modifications in the behavior of the participants, as well as a comparative study in several regions of the country, in order to assess if financial threat affected the Portuguese population equally during the crisis.

Research design

Finally, another limitation of this study was the methodological design. Since this was a cross-sectional study, it was not possible to observe causal inferences.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the resulting data gave us relevant information on how studying and comprehending proactive coping strategies (during times of financial threat) can help to improve the quality of life.

Future studies

Regarding future researches, we think that those should examine the hypothesis model using longitudinal data, in order to address conceptual and methodological issues related to inferences of causality. In addition, they should also include other variables (such as emotional support), in order to have a better understanding of how financial threat relates to life satisfaction.

Finally, it could also be useful to carry out similar studies in other countries, for example, Brazil (since the financial crisis affected European countries first and underdeveloped and/or characterized third world countries afterwards), as we think that it would be very interesting to see how the data would correlate.

Practical implications

We believe that intervention programs based on positive psychology (e.g., behavioral training to increase life satisfaction and individual well-being in times of financial crisis) should be developed. These contingency plans can be developed among the unemployed, a population that was strongly affected by the crisis, in order to empower individuals’ personal strengths and increase their life satisfaction. These behavior reinforcements can be related to exercises that increase the awareness on issues related to coping, such as: (a) problem confrontation; (b) planned resolution of problems; (c) acceptance focused on the process to assume responsibilities; and (d) training on a positive re-evaluation of the facts that were experienced.