Words are rich stimuli commonly used as materials in research across various areas such as linguistics, cognitive psychology, affective priming, social perception, among others. However, words can differ along several variables (e.g., concreteness, imagery, age of acquisition) that can impact the way they are processed. Sometimes the characteristics of the stimuli themselves are the object of the study but, in others, researchers need to equate stimuli sets on these characteristics to insure the internal validity of their work. Therefore, being knowledgeable about the studies that have collected information on these characteristics is crucial when selecting research materials.

According to Andrews and colleagues (2009), the mental representation of the meaning of the words can be learned through distributional and experiential variables. The distributional variables refer to “how words are statistically distributed across different spoken or written texts” (Verheyen et al., 2020, p. 1109), and include variables such as written frequency, mean bigram frequency and the orthographic neighborhood size. The experiential variables capture the “perceived attributes associated with the words” (Verheyen et al., 2020, p. 1109), and can be further divided into lexicosemantic (e.g., concreteness, imageability, familiarity and age of acquisition) and affective variables (e.g., emotional valence, arousal); however, as the authors note, it’s not always simple to distinguish them. We should note that, although we are adopting this form of classifying the variables, other conceptualizations also exist (Brysbaert et al., 2019). This review focuses on studies that have reported norms for lexicosemantic and affective features of European Portuguese (EP)1 words and norms of free association of EP words.

Studies aiming to gather information on experiential variables of words usually require participants to provide their subjective assessment regarding specific features that they think best describe the words (Kremer & Baroni, 2011); this is based on their mental representation of the presented concept (Hyde & Jenkins, 1973; Kremer & Baroni, 2011). It is known that some experiential variables influence the way words are processed in various cognitive domains. For example, in memory, concrete words (that is, words that refer to things that may be experienced by the senses, such as chair) are better encoded and, therefore, better remembered than abstract words (that is, words not referring to material things, or that cannot be experienced by the senses, such as happiness), a phenomenon known as the concreteness effect (Paivio, 1991). On the other hand, Kousta and collaborators (2011) reported that, in semantic decision tasks, abstract words seem to take a processing advantage when compared to concrete words. However, as pointed out by the authors, this advantage seems to be (at least partially) explained by the fact that abstract words have more affective associations.

The effect of emotional valence (i.e., if a word has a positive or a negative emotional connotation) in cognition has also been exploited. For example, Carretié et al. (2008) conducted a lexical decision experiment in which participants had to identify if a string of letters corresponded to a word or not; importantly, the presented words differed on emotional valence (compliments, insults and neutral adjectives). Participants not only were more accurate, but also faster, at responding to compliments (positive-valenced words) than to insults (negative-valenced words).

Another example is animacy, which refers to whether something corresponds to a living / animate or a nonliving / inanimate entity (Caramazza & Shelton, 1998; Félix et al, 2020). Animacy has been identified as the best predictor of free recall, so people tend to recall animates (e.g., people and animals) significantly better than inanimates (e.g., objects; Nairne et al., 2013; see also Aka et al., 2020). The second-best predictor of free recall, identified by Nairne et al. (2013), was imageability, that is, the ease with which a word produces a mental image (e.g., television has high whereas evidence has low imageability). In spite of the fact that imagery and concreteness (mentioned above) correlate highly (r=.88, Soares et al., 2017), studies have revealed differences between them. For example, although concrete words tend to evoke a mental image more easily than abstract words (e.g., Paivio et al, 1968), some abstract words (namely, those denoting affective states; e.g., happiness), although scoring low on concreteness, possess high imageability ratings; in these cases, the high correlation between imagery and concreteness is not observed.

The variable age of acquisition (AoA) is the estimated age at which a specific word was introduced in the individuals’ vocabulary. This variable was been reported to be a significant predictor of word naming latencies (that is, when reading aloud, words that are acquired earlier are read faster than those acquired later), as well as of lexical decision latencies and accuracy. The influence of AoA in the cognitive processing of stimuli (namely, words) has been named the AoA effect (Cortese & Kahanna, 2007).

The individual experience with a word also influences the way it is processed. Such experience might be operationalized by subjective frequency (that is, a rating of how often a person is exposed to the word) or familiarity (i.e., the degree to which one finds a word familiar, considering one’s mental lexicon; Kuperman & Van Dyke, 2013). For example, the more frequent a word is considered to be, the faster one reads it (Kuperman & Van Dyke, 2013). Even though subjective word frequency is sometimes used to indicate familiarity, these variables differ in important ways. For instance, a regression analysis performed by Balota et al. (2001) revealed that subjective frequency provides a better index to the exposure to a word than familiarity, whereas the later seems to relate more to a series of other words’ characteristics (e.g., meaningfulness) than subjective frequency.

The semantic relatedness among stimuli is another variable of broad interest. This variable expresses how close two words are in terms of meaning; for example, words from the same category are semantically related (e.g., dress and shirt are both clothing), as are words that attempt to define another (e.g., apples are red; McNamara, 2005). Semantic relatedness can be captured in free association norms. In free association tasks, participants are usually asked to produce the first word that comes to their minds (target) when presented with a specific word (cue); the association between the cue and the target is often a lexicosemantic association (Altarriba et al., 1999), although links of other nature can also be evoked (e.g., phonological or lexical). Moreover, these norming studies provide evidence about the strength of association between two words (i.e., the likelihood that a particular target occurs in the presence of that cue). It is possible to calculate the cue-to-target (forward strength), as well as the target-to-cue strength of association (backwards strength; Nelson et al., 1998). The former is relevant in predicting free and cued recall (Nelson et al., 2000), whereas the latter has been especially used to study the occurrence of false memories after the presentation of lists of words (Carneiro et al., 2011; Roediger & McDermott, 1995).

Furthermore, free association of words has been used to explore the semantic organization of memory (Hutchison, 2003), and even prospective memory (e.g., McDaniel et al., 2004). It has also been a topic of interest in the investigation of the development of word learning and semantic networks (Chou et al., 2006; Sloutsky et al., 2017), or in studying the neurological underpinnings of semantic processing (Graves et al., 2010). Such characteristic has also been relevant to explore general aspects of memory in clinical groups (Alkathiri et al., 2015).

Given the overall relevance of these word characteristics, norming studies are relevant to support the careful selection of research stimuli. Databases covering lexicosemantic and affective variables are freely available in several languages, such as in Italian (Della Rosa et al., 2010), English (Clark & Paivio, 2004; Rubin & Friendly, 1986; Wilson, 1988), French (Ferrand et al., 2008), Spanish (Hinojosa et al., 2015), German (Schröder et al., 2012) and Croatian (Ćoso et al., 2019), just to name a few. Similar norming studies for EP words also exist; these contain, for the most part, a relatively small number of words and each covers a limited number of variables. Besides, these studies have used different measurement scales (e.g., 9- and 7-point scales to measure the same variable), methods and contexts to collect their data (e.g., data collected individually or in group). They have also been published in various sources making it hard for researchers to easily find and use them. This often “duplicates” the work and efforts of researchers in that they opt to do their own pilot norming studies when they need to control for such variables.

This work aims to minimize this problem and to provide a useful tool for researchers by summarizing the existing norming databases covering lexicosemantic and affective variables, as well as norms of free association in EP. We define the variables as they were used in the corresponding studies and describe the main aspects of their procedures. Finally, we compiled the norming data available in these studies into a single database; it contains all the EP rated words, along with their scores as reported in each of the original studies. In spite of the above-mentioned differences among studies, we present evidence of discrepancies but also of communalities in the gathered data; these suggest that one can use some data from various studies in a safe way.

Method

We conducted our search for databases of European Portuguese words in Scopus and Web of Science, as well as in Portuguese journals - Laboratório de Psicologia, Análise Psicológica and Revista Portuguesa de Psicologia - that are often used to publish this type of work. A couple of studies developed by the authors (one accepted for publication the time this work was being prepared and another currently under preparation that reports two norming studies) were also included in this review.

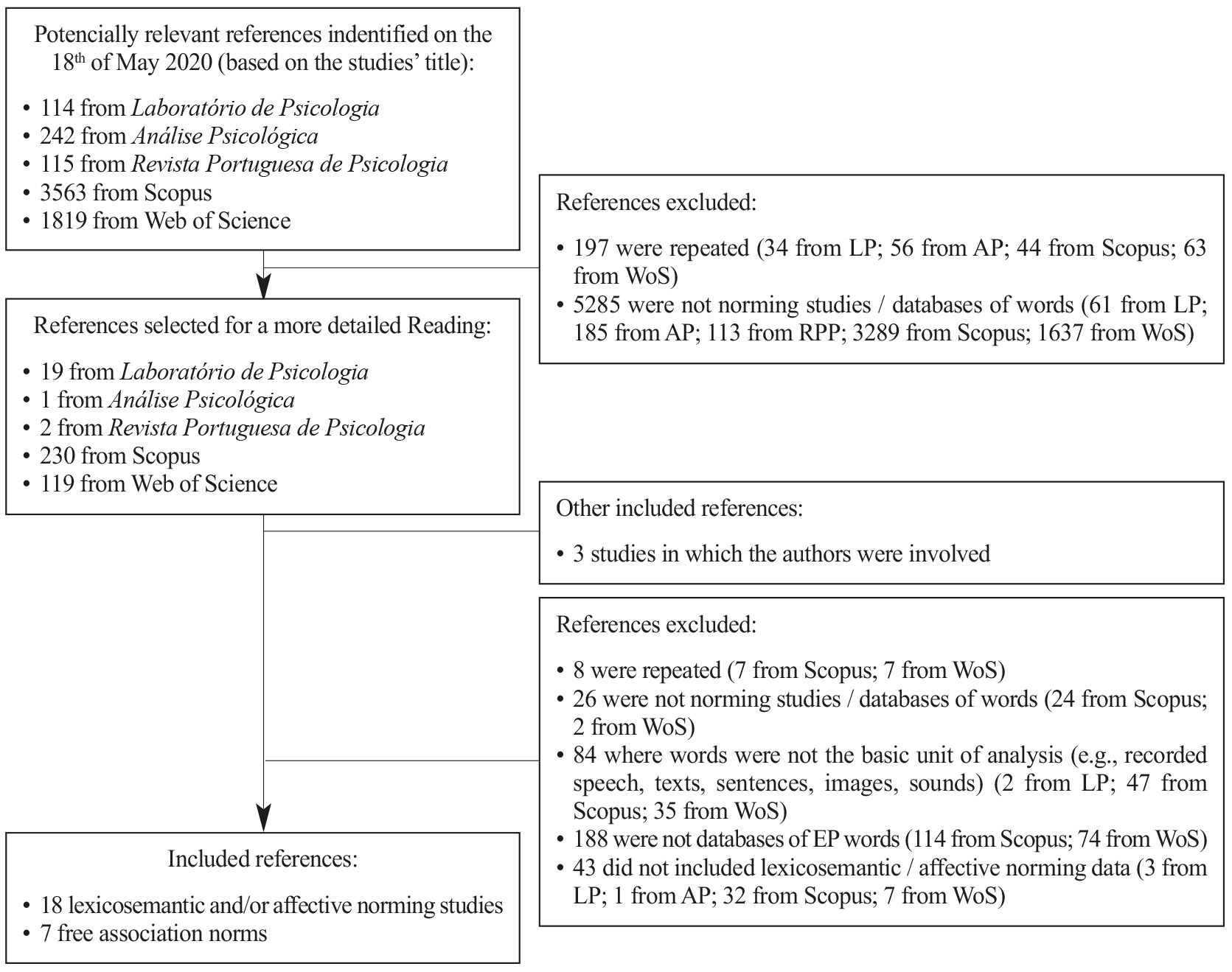

After a literature review on databases of words and lexicosemantic / affective variables (e.g., Rubin & Friendly, 1986; Wilson, 1988), we identified the following search terms of interest: familiarity [familiaridade], frequency [frequência], valence [valência], emotional valence [valência emocional], mental valence [valência mental], arousal [ativação], dominance [dominância], age of acquisition [idade de aquisição], concreteness [concreteza], imageability [imageabilidade], availability [disponibilidade], goodness, concept typicality [tipicidade] and animacy [animacidade]. The following additional terms were also used in the search procedure: word* [palavra*], Portuguese [português], Portuguese tongue [língua portuguesa], European Portuguese [português europeu], word database [base de palavras] and norming study [estudo normativo]. The search was conducted with all these terms in Portuguese and in English (see Appendix 1 for the searched keywords, and the results obtained in each source). We only considered studies that comprised EP written words as their basic unit of analysis (instead of text excerpts or spoken words, for example), that contained lexicosemantic / affective norming data, and that were published since 2000. As language has been changing with the introduction of new concepts (e.g., mouse can now mean both a rat or a computer device; Rodd et al., 2012), norming studies need to be time-adjusted (Comesaña et al., 2014). Thus, this time-period criterion was settled to present an up-to-date review of the existing databases that could be currently of use to other researchers. The search strategy used is presented in Figure 1.

Results

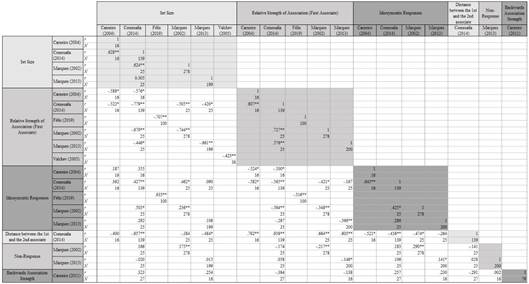

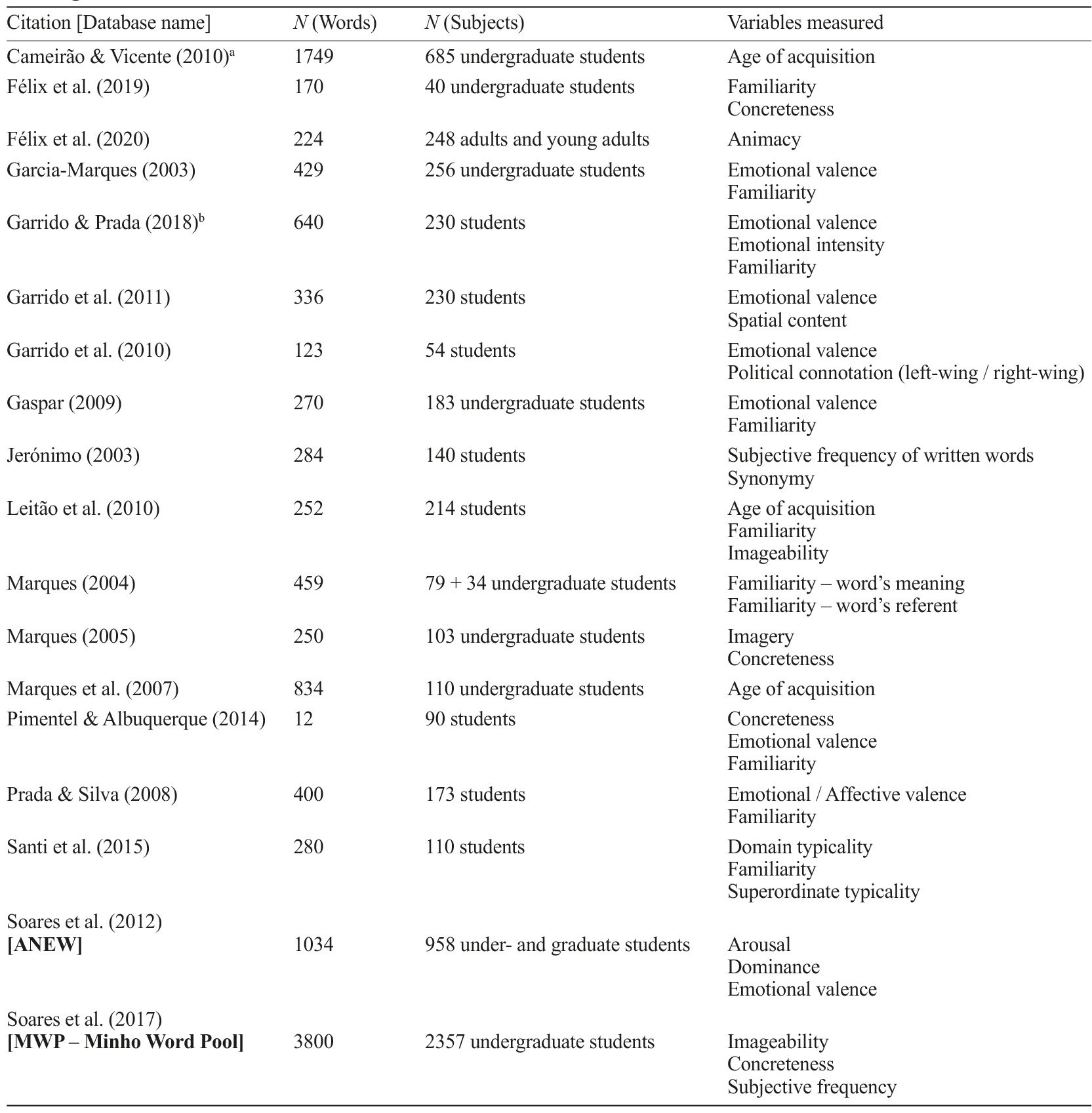

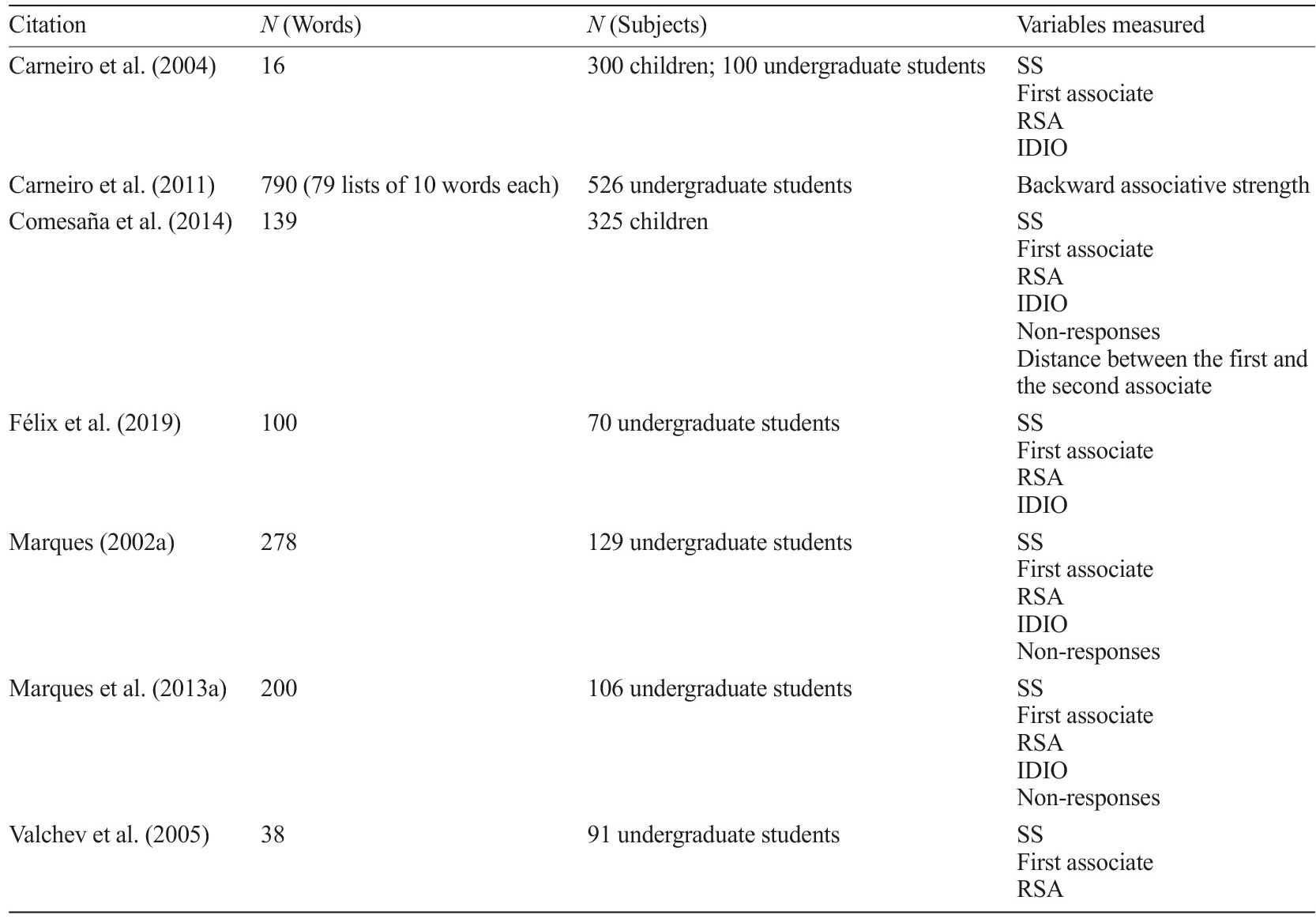

The results of the present research are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 (see also Appendixes 2 and 3 for more details), organized by alphabetical order of the first author’s surname. We found 25 studies that met our inclusion criteria. Of those, 18 refer to norming studies on lexicosemantic and affective characteristics and seven on free association norms for EP words. These databases include different categories of words, such as nouns (in most studies), adjectives, verbs, and / or adverbs. All the considered databases were accompanied by supplemental materials and / or appendixes containing the norming information and are freely available.

Table 1 Summary of studies reporting data on lexicosemantic and / or affective variables for European Portuguese words

abNotes. Cameirão and Vicente (2010) report presenting AoA ratings for 1749 words, although we found that 31 of those words appear twice; Garrido and Prada (2018) present norming data for 320 EP words and 320 English words. See Appendixes 2 and 4 for detailed information on each study.

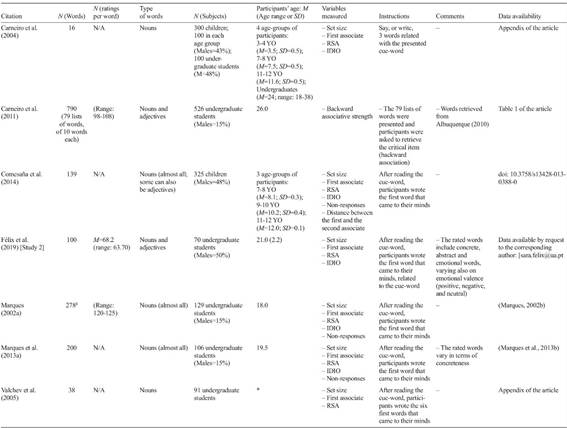

Table 2 Summary of the studies regarding the free association norms for European Portuguese words

Notes. IDIO=Idiosyncratic responses; RSA=Relative Strength of Association; SS=Set size. See Appendixes 3 and 5 for more detailed information about these studies.

The searched databases comprise, on average, 523.08 words (SD=780.45; Range: 12 - 3800). The variables covered by these databases, along with the definitions used in each study, are provided in Appendixes 4 and 5. The mean sample size was of 317.64 participants (SD=475.45; Range: 40 - 2357). Twenty-two studies used samples only of university students, one also included non-university adults (Félix et al., 2020), another also included children (Carneiro et al., 2004), and one collected data only from children (Comesaña et al., 2014).

We also created a database containing all the scores reported in the studies, comprising a total of 5346 words2. This database is available in our Open Science Framework project (https://osf.io/9ta3y/). In some of the referenced works, the authors provided their collected information along with information on other variables that was extracted from other studies. For example, Cameirão and Vicente (2010) collected new data on age of acquisition but also presented data on the variables of familiarity, imageability, concreteness, frequency, grammatical class, length, orthographic and phonological neighbors that were retrieved from other studies. In our database we only present the new information provided by each study.

We start by describing the data gathered from the 18 norming studies on lexicosemantic and affective variables. For most variables, words that are included provide assessments that range from the lower to the upper values of the rating scales. Also, 11.3% of the words have data available for only one variable and each word was rated in just one study. For most of the words (87.5%), norming data for two or more variables is available (1.2% of the words contain information only of free-association norms or typicality). Within this last group, 89.9% of words (representing 78.7% of the total words from the overall database here presented) contain data collected from different studies; however, for roughly a quarter of those words (22.9%; 20.1% of the total words), data on the same variable were collected in various studies3. These results not only reveal that most of the ever-rated EP words are characterized on different lexicosemantic and / or affective variables, but also that these data are repeated (or “duplicated”) among studies.

Most norming studies conducted in Portugal collected data on familiarity (nine studies4) and on emotional valence (eight studies). However, as the norming studies on familiarity considered a relatively small number of words, we only have information on this variable for about 27.7%5 of all words; differently, about 41.8% of all words have been rated for emotional valence. Information on concreteness, subjective frequency and imageability is available for about 73.0% of all the rated words; these are the variables best represented in the presented database, largely due to the high number of words rated in Soares and collaborators’ work (2017).

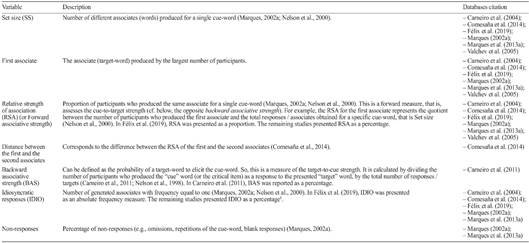

In order to explore communalities in the ratings obtained for the same word and variable between / among studies, we calculated Pearson correlations; these are presented in Appendix 6. Some of the obtained correlations included a small number of items; we opted to present only the correlations that included at least 15 data points (Bonett & Wright, 2000) which provide more reliable information.

High and significant correlations between ratings of the same variable were obtained across studies (.707<|r|<.996). For example, the correlations among the three studies providing concreteness ratings varied between .938 and .968, and for AoA between .884 and .943. One exception can be found for the variable of familiarity (.032<|r|<.957) where the disparate results were mostly due to the adoption of different scales and concepts across studies6. Overall, the results revealed consistency on the normative data collected over the last 20 years in different studies.

An inspection of the relations between variables that have been described in the literature provides another form of validation of the presented data. Although an in-depth consideration of these relations is out of the scope of this work, we describe a few potentially interesting results. Statistically significant moderate to high correlations were obtained between concreteness and imageability ratings (.680<r<.960), as expected according to Paivio and coworkers (1968). The values for familiarity and subjective frequency were also moderately correlated (average of the absolute values of the various correlations=.627) in agreement with the results obtained by Balota et al. (2001). Significant moderate and negative correlations were found between AoA and imageability (-.859<r<-.572), a relation that has been reported in the literature (Brown, 1957). In sum, the confirmation of these relations suggests that one can reliably use the present data.

Regarding the free association indexes, Appendix 7 reports the correlations obtained among studies. Again, only correlations that included a minimum of 15 datapoints are reported. The idiosyncratic responses index varied between studies, revealing the heterogeneity among people when generating a single associate. Not surprisingly, moderate negative and significant correlations (-.420<r<-.779) were obtained between the relative strength of association (of the first associate) and set size; this is because RSA is a quotient containing SS in the denominator (thus, the higher the SS, the lower RSA is).

Discussion

This study provides an overview of the norming studies of EP words published in the last 20 years. These include both lexicosemantic and affective norming data of words (e.g., familiarity, animacy and arousal) as well as free association norms of words. We also provide a brief definition of the variables for which data are presented along with information on the corresponding studies.

Our search revealed the existence of 25 norming studies that, on average, provide information for a reasonable number of words. The obtained results not only reveal that information on several experiential variables is available for most of the EP rated words, but also that data are frequently spread across different databases (68.1% of times). This dispersal of information comes as at a cost to researchers who have to spend more time searching for databases and aggregating dispersed information. In addition, data collected on the same variable are sometimes (for 20.2% of the words) repeated or duplicated, as they were collected in different studies. Although replication studies are needed (e.g., to update the norming data of a language in permanent change; Comesaña et al., 2014), it might also correspond to an unnecessary duplication of work and a waste of researchers’ time and resources in collecting data that are already available; the high correlation values here reported among the data obtained for the same variable in different studies (at least for some of the variables) support this idea. For all these reasons, the aim of presenting a single database that brings together the norming data for European Portuguese words made available in the last 20 years, is more than justified.

Although these norming studies cover a variety of dimensions, other word variables of potential interest can be found in the literature that still lack research in our language. Some examples of that are: goodness, meaningfulness (Rubin & Friendly, 1986), pleasantness (Clark & Paivio, 2004), gender association / ladenness (Scott et al., 2019), number of senses / meanings (Miller, 1995), sensory experience (Juhasz & Yap, 2013), and body-object interaction (Pexman et al., 2019). For more information on these variables, see the cited studies.

Regarding the available data here reported, some disparity seems to exist in the way some of the variables were defined and how they were measured; this somehow mimics the state of the international literature. For example, there are various operationalizations of subjective frequency and different conceptions on how it differs from familiarity. In some studies, these two terms are used interchangeably (e.g., Garcia-Marques, 2003; Jerónimo, 2003). However, the instructions given to the participants direct them to a familiarity or a subjective frequency judgement. Although familiarity and subjective frequency are related variables (see Appendix 6), Balota et al. (2001) argue that subjective frequency may be a better estimate of the subjective exposure to a word than familiarity; this relates to the fact that some of the instructions used to assess familiarity seem to be vague, allowing participants to support their familiarity ratings on other variables or aspects.

Two other concepts that have raised debate are those of pleasantness and emotional valence. Although they have been used, to some extent, indiscriminately in the literature (Whissell, 2008), they might appeal to different meanings. According to Scott and colleagues (2019) emotional valence corresponds to a measure of value where items rated as more positive are thought to be good, whereas those rated more negatively are considered to be bad. On the other hand, pleasantness seems to refer more to the feelings of the rater regarding the word’s connotation (Gelin et al., 2017). More recently, based on a set of factorial analysis, Brysbaert and coworkers (2019), have argued that pleasantness and emotional valence seem to belong to the same factor, under a larger umbrella called valence. In our search we found a set of studies reporting both emotional valence and a broader measure of emotionality.

As denoted in Appendixes 2 and 4, across studies that report information on a given variable, different conceptions and operationalization of that variable, as well as methods and scales have been used. We caution the reader to take these elements into consideration.

We should also note that we only report the studies obtained from our literature search strategy which misses unpublished studies (e.g., data reported in Master or PhD unpublished thesis) and studies published prior to year 2000. For example, there is an unpublished study on free association norms by Albuquerque (2010) that is frequently referenced in publications that have used it (this study is available upon request to the author). In that work, a total of 1264 students provided free association norms for a set of 489 words (including nouns and adjectives). In that study, participants were asked to write down the first word that came to their minds when presented with the cue-word.

The EP studies on free association norms of words contain a low number of words each, as compared to studies such as the South Florida Free Association Norms (Nelson et al., 1998). Although free association research has slowed down through the years, it remains an interesting field of research, as it is considered by many to be a way of accessing semantic memory. As words are versatile stimuli, used in several research domains (e.g., neuropsychology, social perception), it is important to control for the semantic relatedness of words when selecting them for research experiments, as it can bias some results (e.g., memory recall; Buchanan et al., 2006).

We should also acknowledge the existence of other EP word databases that cover word variables that were not of interest to the present work or that did not show up in our search. Examples are the PORLEX (Gomes & Castro, 2003), P-PAL (Soares, Iriarte, et al., 2014), SUBTLEX (Soares et al., 2015), ESCOLEX (Soares, Medeiros, et al., 2014), the corpora from the Centro de Linguística da Universidade de Lisboa (CLUL, 2019) - including CORLEX (Nascimento, 2003) -, or the Corpus do Português (Davies, 2012). Studies containing norming data for stimuli other than written words were also excluded from our review. Thus, for example, we did not include the Domingos and Garcia-Marques’s study (2008) which provided norming data for nonwords, or the Soares and colleagues’ work (2013) with norming data for sounds.

It is interesting to note that the studies reported in the present work collected their normative data mostly with young adults. Only a couple of studies on free association norms included younger samples. While this is understandable, as most research that will benefit from these norms will most likely be conducted with these age groups, the growing interest in other age groups (namely older adults) could lead to the development of normative studies with those specific groups. While one might think that the assessment of some word variables could be relatively stable across the life span, others could vary. For example, the words acácia [acacia], traineira [trawler], or alpendre [porch] which were rated as not very familiar by the young adults would probably be more familiar to older adults (Garcia-Marques, 2003; Marques, 2004). Also, Duarte et al. (2007) reported a significant interaction between age (young vs. older adults) and animacy (animate vs. inanimate words) in a familiarity rating task. Post-hoc analysis revealed that animates received significantly higher scores of familiarity than inanimates only in the older adults group; for the younger adults groups, the difference was non-significant. There are also age differences reported in the literature on other variables. For example, older people seem to rate negative stimuli as more arousing than young participants; on the other hand, they seem to rate positive stimuli as less arousing than young people (Fairfield et al., 2017).

Finally, with this study, we make available a database that congregates the information from the various Portuguese norming studies on the word variables here considered. We hope this resource will be of use to other researchers needing to select stimuli for their studies.