Introduction

The characteristics of the labour market and the workers of the present generation are quite different from the previous ones. The relationship with work has become more dynamic, making it difficult to identify factors that affect health (Tetrick & Quick, 2011). The increased longevity and duration of active working life is compromised by the growth of chronic diseases (including mental issues) that lead to the decline of health and ability to work (Cooper & Bevan, 2014).

Disrespectful and harmful behaviours in the workplace are a well-known phenomenon among health care professionals, present since undergraduate classes, and permeating organizational health care culture Although it is not a new topic, the magnitude of this problem is not yet fully known, and effective strategies addressing this issue are not usually in place, partially due to the few empirical studies testing the relationship of the various important concepts which might inform us on how to develop evidence-based interventions (Gardner, 2020).

Data regarding Portugal indicate that 2/3 of the nurses have high levels of emotional exhaustion (Jesus et al., 2014). For 12 years, a 52.4% rate of burnout syndrome regarding doctors was reported (Frasquilho, 2005). In 2016, a study conducted by the Portuguese Medical Association indicated a high level of emotional exhaustion for 66% of the doctors, while 39% had a high level of depersonalization and 30% had a decrease in their professional achievement (Vala et al., 2016). These facts illustrate the need to understand what can promote better mental health for these professional groups.

Many occupational health studies have pointed out that conditions in the work environment influence workers’ health in various ways, but so far, the primary target of health care interventions has been the individual rather than the organization (i.e., employee adjustment rather than improving working conditions; Burke, 1993). However, health promotion and maintenance should not be seen as an individual problem. The vulnerability of workers’ mental health and well-being is not only inherent to the individual, but derives from their circumstances and the environment and should be treated at group level, taking into account social and organizational factors (Martin et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2013). According to Cooper and Bevan (2014), this focus “shift” can be beneficial for the organisations themselves, by helping reducing sick leave and the number of accidents and by promoting increased involvement, commitment and productivity.

Literature review

Changing work conditions might be easier than changing individuals, and also more effective, since work conditions affect all individuals that experience them. Therefore the broader the conditions, the higher the number of employees that might benefit from them.

On the organizational level, studies have also shown the positive association between empowering work environments and individual health outcomes (Laschinger et al., 2004; Laschinger, Finegan, & Shamian, 2001). Structural empowerment refers to a type of work environment (rather than an individual characteristic), that provides workers with effective access to a range of resources and enhances performance, allowing the individual to develop knowledge and skills and to evolve within the organizational structure (Kanter, 1981). Therefore, access to relevant information, resources and support is essential to structural empowerment (Laschinger, Finegan, & Shamian, 2001), which affects employees in terms of their self-efficacy and emotional exhaustion (Biron & Bamberger, 2010) and in their job satisfaction (Orgambídez-Ramos & Borrego-Alés, 2014; Stetz et al., 2006; Teixeira & Barbieri-Figueiredo, 2015). Structural empowerment is also an effective tool for maintaining a climate of civility (Shanta & Eliason, 2014; Woodworth, 2015). Mikkelsen and colleagues (2000) underline the importance of empowering staff as a key factor for change.

However, Wing and colleagues (2015) demonstrated that even in workplaces with access to empowerment structures, workers’ mental health is affected by the quality of interpersonal relationships. Specifically, the results indicate that incivility partially mediates the positive influence of structural empowerment on nurses’ mental health, reducing this beneficial effect.

In environments with high levels of stress and workload, the first sign of emotional exhaustion is often the lack of care towards others. Disrespectful behaviours can be used to restore a situation of organizational injustice, which can lead to an incivility cycle (Leiter & Patterson, 2014).

These interpersonal behaviours whose intentions are not clear, with a negative nature and violating the norms of respect, constitute uncivil behaviours (Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Schilpzand et al., 2016). Examples include ignoring someone, facial expressions of annoyance, not greeting someone or not sharing necessary information, among others. Despite its low intensity its effects might be significant. There can be long lasting, serious consequences for the individual’s well-being, such as insomnia (Demsky et al., 2018), reduced empowerment and self-esteem, leading to counterproductive work behaviour and work withdrawal, especially for highly committed individuals and with higher job involvement (Kabat-Farr et al., 2018; Welbourne & Sariol, 2017). Its impact depends on the significant recurrence and on its invisibility, which boosts the risk of accumulation of its effects over time (Viotti et al., 2018). On the contrary, civility affects positively workers’ performance, involvement, dedication and the energy put into work (Day & Leiter, 2014).

Civility refers to norms of public conduct associated to “good manners” and its purpose is to facilitate the conditions of the social fabric. It has a social function that determines what is acceptable and what is not, and it reflects the variety of rules shared by different individuals and groups (Bowman, 2011; Bybee, 2016). Civility evidences a respect for others’ identity and opinions, resulting into a treatment of dignity and respect (Von Bergen et al., 2012). Its benefits in the workplace include trust, psychological security, better knowledge networks, greater information flow and opportunities (Porath & Gerbasi, 2015).

To determine civility in a workplace it is not enough to confirm the absence of incivility. Respect and acceptance among workers, a spirit of cooperation and a fair form of resolving conflicts are necessary (Osatuke et al., 2009).

In their review about hostile behaviour in nurses’ workplaces, Crawford and colleagues (2019) identified factors with a negative impact on civility. These include lack of progression opportunities, of supervisor support, of empowerment and autonomy at work, and of human or financial resources. All these factors highlight the acknowledgement of the role of structural empowerment in promoting civility.

The quality of relationships at work, are known predictors of mental health (Eurofound, 2012). For more than 25 years NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) has referred the importance of the psychosocial environment at work on employees’ psychological health (Day & Randell, 2014).

On the other hand, experience and seniority might play a role in these relationships. Teixeira and Barbieri-Figueiredo (2015) point out that older and more qualified nurses perceive greater empowerment. This might be because they know their workplace better and have informal networks which might help them to acquire necessary resources. Hawkins and colleagues (2019) identify uncivil behaviours as an international problem especially for new nurses, with repercussions on their mental health, and consequent intent to leave and negative impact on their health care quality. It is therefore expected that nurses new to the profession or the institution might be at greater risk.

Given the negative effect of incivility on the relationship between structural empowerment and mental health (Wing et al., 2015), and the positive effect of structural empowerment on interpersonal relationships in the workplace (Manojlovich & Laschinger, 2007; Miller et al., 2001), it seems appropriate to investigate whether relations of civility at work could mediate the relationship between structural empowerment and mental health, amplifying the effect of the latter. In other words, in a work environment that offers the necessary conditions for proper development and good professional effectiveness (structural empowerment), does civility improve workers’ mental health? Moreover, given the fact that the negative impact of incivility depends on its recurrence and accumulation of its effects over time (Viotti et al., 2018), does civility improve workers’ mental health especially for professionals with a longer work experience in the hospital?

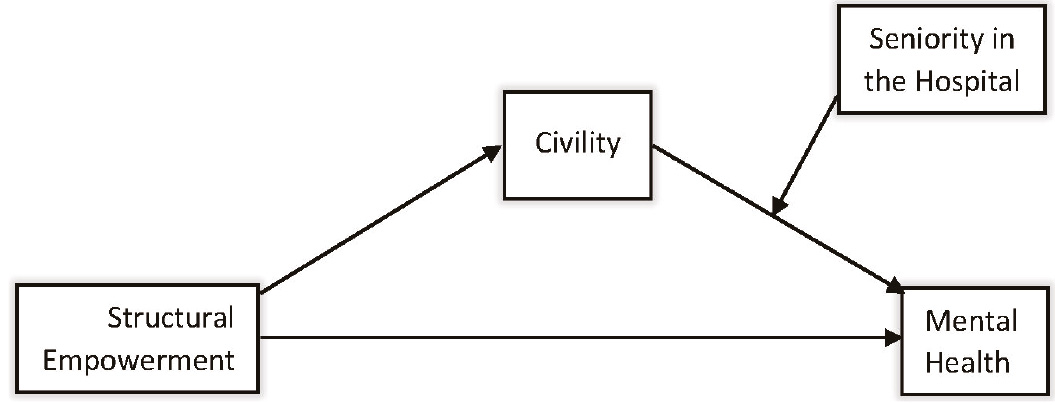

The objective of our study was to verify if better working conditions, as defined by structural empowerment, increase workers’ mental health through the promotion of civil behaviour in the work team. We also expect that the time factor associated with working in the institution may modify this effect on employees’ mental health. The theoretical model is presented in Figure 1.

We hypothesise that:

H1: Structural empowerment will be positively associated with civility;

H2: Civility will be positively associated with mental health;

H3: Civility will mediate the relationship between structural empowerment and mental health;

H4: Seniority (in the hospital) will moderate the indirect effect of structural empowerment on well-being. Specifically, civility will mediate the relation for those whose seniority is higher.

Method

Sample and procedure

Participants comprised 303 health professionals employed in a Portuguese Hospital managed by a public-private partnership1 in the Greater Lisbon area. The sample was composed of 77.08% women and the average age was 35 years old (SD=9.96). Most participants were nurses (57.76%), and operational assistants (26.73%). The remaining 7.26% were technicians and 5.61% doctors2. The participants had been working in the hospital for a period between less than 6 months to more than 30 years (M=6.18; SD=6.60).

Our study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board. Participants were surveyed in December 2015. Responses were voluntary and anonymity and confidentiality were assured. This information was included in the cover sheet of the questionnaire distributed in paper format. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data was collected via ballot boxes available for this purpose, placed in several locations around the hospital and opened by the research team. The questionnaire consisted of the scales indicated in the measures section plus a section on sociodemographic data.

Measures

Civility. Civility was measured by the Portuguese version of the Workplace Civility Scale (WCS; Osatuke et al., 2009), ECT - Escala de Civilidade no Trabalho (Nitzsche, 2015). The scale score consisted of the mean of 8 items (α=.89), of which higher scores indicate a perception of greater civility in the workplace (e.g., “In my work group, people treat each other with respect” and “In my work group, there is a spirit of cooperation and teamwork”). Respondents used a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 - “I strongly disagree”, to 5 - “I strongly agree”).

Structural empowerment. Structural empowerment was assessed by the Conditions of Work Effectiveness Questionnaire II (CWEQ-II; Laschinger, Finegan, Shamian, & Wilk, 2001, Portuguese version by Orgambídez-Ramos et al., 2015) scored through the mean of 12 items (α=.87). Higher scores indicate greater structural empowerment (e.g., “To what extent do you have the possibility to develop new skills and knowledge?” and “To what extent do you have access to information on top management objectives?”). The response scale was a five-point Likert-type one (from 1 - “not at all” to 5 - “a lot”).

Mental health. Mental health was measured by using the mental health component of SF-36v2 MOS health scale (Portuguese validation by Ferreira, 2000a,b). It is scored with the sum of the values of 5 items (α=.84), after inverting the negative ones. The participants were asked to evaluate how they felt in the previous four weeks (e.g., “Did you feel very anxious?” and “Did you feel depressed?”). Respondents used a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 - “always”, to 6 - “never”).

Data analysis

Data were submitted to the statistical analysis program, IBM © SPSS © Statistics, version 22.0. The different scales used to measure the concepts of structural empowerment, civility and mental health had different amplitudes. In order to homogenize them, all scores were converted to a scale from 0 to 100.

A moderated mediation model was tested with conditional analysis using PROCESS (see SPSS; Hayes, 2012), applying the bootstrap technique with 5.000 samples and 95% confidence intervals adopting model 14.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Due to ECT’s recent adaptation to Portuguese population, and due to the fact it had taken place with a sample of a different professional area from the one in our study (catering and hotel professionals, not health professionals), an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was carried out for this sample, in order to contribute to the further development of this scale in the Portuguese context. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was .90 and the Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was significant [χ 2 (28)=1286.640, p<.001].

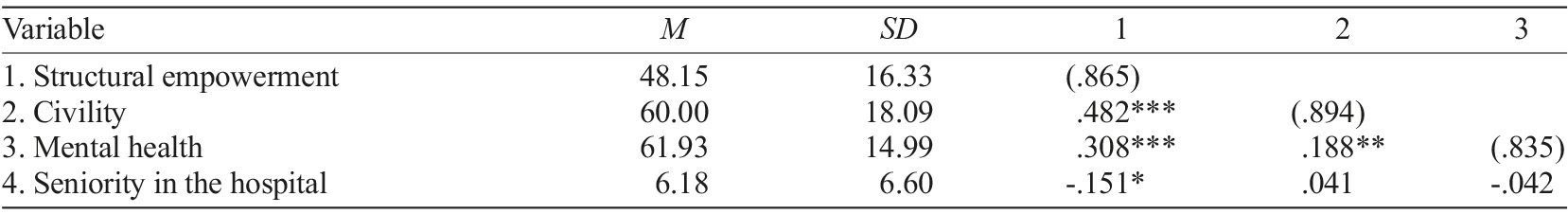

Table 1 reports the Pearson’s correlations of the studied variables. All the correlations among the variables showed significant associations in the expected direction.

Hypothesis testing

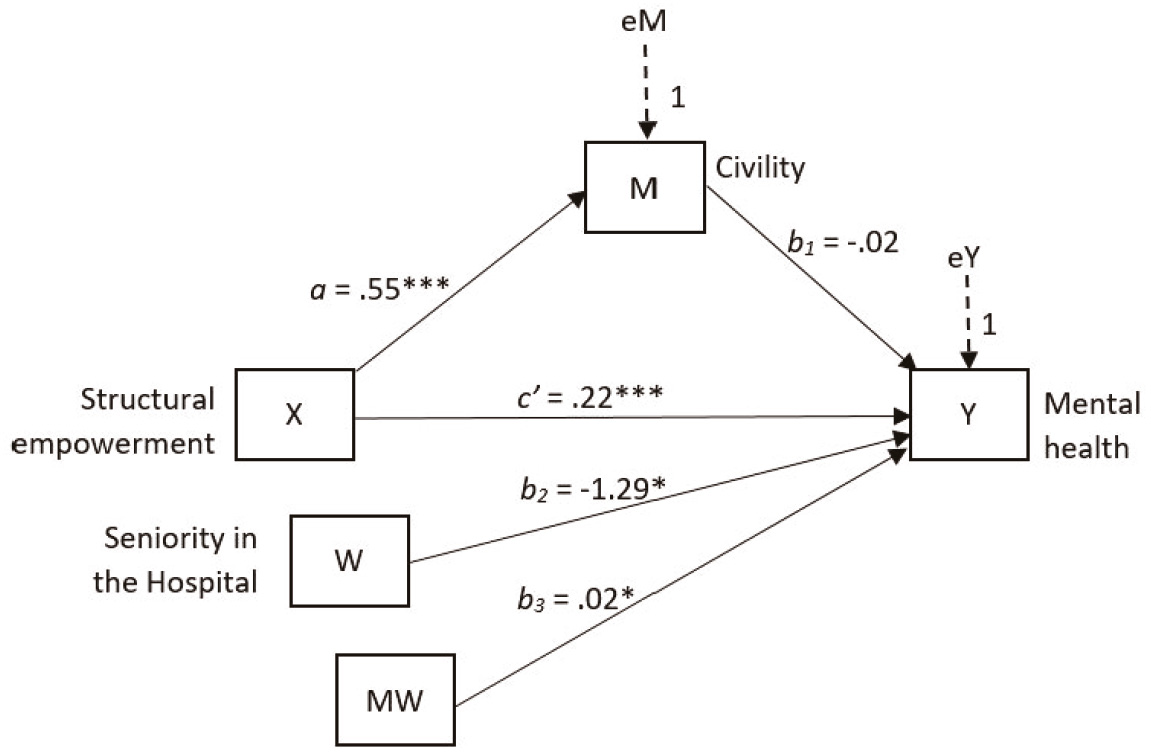

Results of the first step of the model (see Figure 2) showed that structural empowerment (a=.55, t 1,265=9.23, p<.001) accounted for 24% of the variance in civility [F 1,265=85.23, p<.001, R 2 =.24].

The second step of the model, which contemplated the combination of the effect of structural empowerment (c’=.22; t 4,262=3.55, p<.001), civility (b 1 =-.02; t 4,262=-.35, p>.05), seniority in the hospital (b 2 =-1.29; t 4,262=-2.44, p<.05) and the interaction between the latter two (b 3 =.02, t 4,262=2.48, p<.05), was statistically significant and explained 13% of the variance of the dependent variable, mental health [F 4,262=9.62, p<.001, R 2 =.13].

Figure 2 Conditional process model corresponding to the indirect effect of structural empowerment on mental health in the statistical form

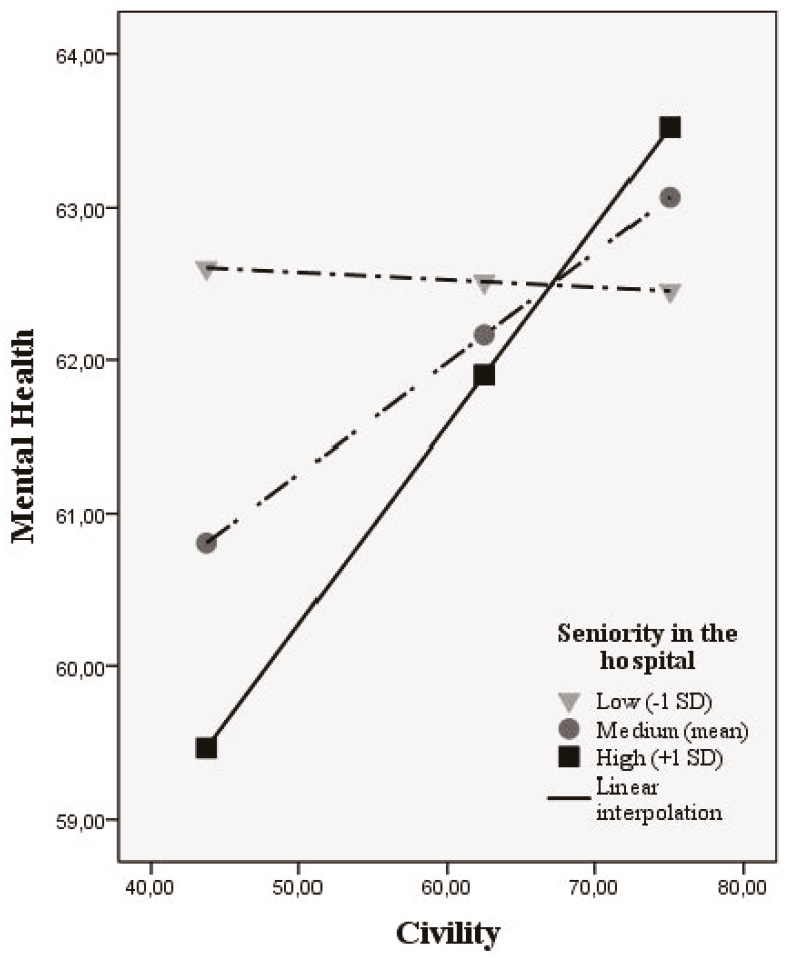

The moderated mediation index was .0107 [CI=.001, .02] and statistically significant. For low levels of job seniority3, interaction with civility had an effect of - .01 [CI=-.09, .07]; for average levels of seniority in the hospital, the interaction with civility had an effect of .05 [CI=-.004, .12]; for high levels of seniority in the hospital, the interaction with civility had an effect of .12 [CI=.03, .23]. Only in high levels of the moderator (seniority) was the effect of the mediator statistically significant. The interactions are displayed in Figure 3.

Discussion

We aimed to understand the relationship between structural empowerment in the workplace and psychological health via the mediating role of civility at different levels of seniority in the hospital. The results of the moderated mediation model confirm our hypotheses. In our sample, structural empowerment increases workers’ mental health through the presence of civil behaviour in the work team, but only for workers with longer seniority. In line with previous studies, structural empowerment has a direct influence on mental health (Bakker et al., 2005; Bakker et al., 2004; Laschinger, Finegan, Shamian et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2001; Schütte et al., 2015) reinforcing the importance of structural empowerment factors included in Kelloway and Day’s (2005) healthy workplace model.

Regarding H1, the effect of structural empowerment on civility was confirmed, in line with Kanter (1981), Miller et al. (2001). Therefore, in our study, individuals who perceived higher access to empowerment structures reported higher values of civility. In accordance with several studies (Manojlovich & Laschinger, 2007; Miller et al., 2001; Shanta & Eliason, 2014; Woodworth, 2015), in fact, this organisational factor is relevant for the promotion of good quality interpersonal relationships in the workplace. However, on the second step of our model we find that civility does not significantly predict mental health (H2). This can be explained by the fact that the effect of civility on mental health is conditional to the values of the moderator: in workers with high seniority, civility is associated with mental health. Therefore, H3 is partially confirmed; simultaneously, we find support for H4. The mediating effect of civility on mental health is significant at higher levels of the moderator, which means that the mediation is significant only for hospital workers with higher seniority.

Similar to Wing and colleagues (2015) findings, that incivility reduces the beneficial influence of structural empowerment on workers’ mental health, our study shows that civility also mediates the relation these variables, but positively. However, this seems to be a more complex association, since seniority plays a moderator role. Indeed, short tenure in the workplace might not be enough to make the effects of civility salient on workers’ health.

Civility seems more important for the health of those who have been working longer at the hospital. The effects of incivility are perceived after an accumulation of its effects over time (Viotti et al., 2018) due to its ambiguous and low intensity nature, which requires time to be recognised and processed (Cortina et al., 2017). The quality of the organisational environment may not fully emerge during a short period (Kim et al., 2016), and this is probably the reason why the effects of civility on mental health are significant only for those with higher seniority.

Teixeira and Barbieri-Figueiredo (2015) point out that older and more qualified workers perceive greater empowerment. It seems likely that longer-term professionals in the organization have had more time to create socio-political support networks and better information circuits, a greater degree of control over their functions, greater responsibilities and authority. Thus, they will have better conditions for structural and psychological empowerment (Spreitzer, 1996). In our sample the results also showed that seniority in the hospital has a negative effect on mental health, which means that as the length of stay in the institution increases, professionals’ mental health decreases. In line with this, Wing and colleagues (2015), found that the positive effect of the structures that facilitate an effective and motivating work can be reduced by incivility. Although incivility is not the mere absence of civility (as previously stated), perceived low levels of civility, lacking some of its characteristics (e.g., cooperation, just conflict resolution) might not be enough to support structural empowerment’s benefits. In addition, lack (or low levels) of cooperation and/or justice in conflict resolutions, although conceptually different from incivility, are indicators of poor work conditions, and might have the same detrimental effect.

It is thus possible that the effect of long tenure in the hospital on workers’ mental health could be negative only when it is associated to low levels of civility. In fact, in our results, the interaction between civility and seniority in the hospital had a positive effect on mental health. It makes sense to assume that individuals who perceive their workplace as civil do not suffer the negative effects of working for a long time at the institution. As work time at the institution increases, its effect becomes negative if combines with low civility but positive in case of high civility at the workplace.

The existence of a psychosocial variable (civility) that can be stressed to reverse the negative effect of working for a long time in the same institution, creating a positive effect on mental health, could be used as an instrument to cope with psychosocial risks by promoting positive work dynamics, but this relation needs further testing.

Limitations

The results obtained from our sample may be influenced by several specific factors due to our method. Firstly, the cross-sectional design of our study narrows the conclusions concerning the causality of the association between the variables. Secondly, our civility measure presents items that refer intra and extra team dimensions (colleagues, leadership and organizational). A general evaluation of civility can affect the result if there are discrepancies between these levels (Walsh et al., 2012).

Social desirability might also be a factor - participants may answer with average values or slightly above, projecting a positive image of their team. Assessing leadership is generally a sensitive point. The corresponding score may have been skewed to slightly higher values. On the other hand, since the participants were volunteers, they are probably not the most dissatisfied employees within the organization, which can also otherwise justify our values.

Our sample included several professional groups (doctors, technicians, operational assistants and a majority of nurses) but the restricted number of participants of some may prevent a comparative analysis. We believe that the reality of the various professional groups is substantially different and analysing them together may cloud some results. We also had to group different services (operating room, emergency room, external consultation) but each has its own characteristics, stress level and team dynamics. A clear example would be the differences between the emergency room and the external consultation teams.

Finally, all our data come from a single Hospital. If there are specific conditions particular to this institution, the results, although strictly speaking correct, might inform us no longer about the general civility and empowerment dynamics, but about the institutional dynamics.

Future research

To our knowledge, this is the first study that tests the mediating role of civility between structural empowerment and employees’ mental health. Therefore, the results can only be thought of as indicative, and need further testing on other samples, to solidify evidence. Moreover, it might be interesting to discriminate between public, private and public-private hospitals, since different types of administration might provide different levels of structural empowerment. Many work conditions that make up or influence structural empowerment and team civility are enhanced or limited by leadership. The type of leadership is also a relevant variable to take into account when studying the concepts of our research. Finally, it might inform us of the depth of the civility/incivility problem if medical errors and patient satisfaction were crossed with our type of results.

Conclusions

Health professionals who have higher structural empowerment, perceive high civility in the workplace and have been working in the hospital for a longer time report higher mental health. Among those who have been working in the hospital for less time, civility was not significantly related to mental health.

Scientific literature about occupational health points out that work environments with supportive relationships, respect, trust and cooperation promote better results, both in terms of performance and safety. The importance of this type of relationships (civility) is clear in our results, although its effect seems to depend on other variables such as tenure.

The results of this study can be used as a starting point for further experimental research in order to validate the causality of the relations between the studied variables and to design future interventions that meet the needs of these professionals (eventually different in specific stages of professional development/career), improving their work contexts, their health and effectiveness, on which the quality of services provided to the users depends, and consequently the health of all of us.