Introduction

Aversive personality traits, such as a cohesive group of factors that must be studied together, have only recently aroused the interest of researchers (Furnham et al., 2013; Jones & Paulhus, 2014; Lyons, 2019). The Dark Triad (DT), composed of three distinct personality traits (machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy), but with common characteristics, is the one that has received the most attention after being conceived by Paulhus and Williams (2002) (Jakobwitz & Egan, 2006; Jones & Paulhus, 2014). Machiavellianism is characterized by manipulation, which is a means to an end (obtaining instrumental and/or social benefits) and an absence of empathy (Gonçalves & Campbell, 2014; Kowalski et al., 2018). Narcissism is characterized by the belief in superiority, the need to dominate and be admired in an excessive way, exploitation with others for one’s own benefit, and an absence of empathy (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2014; Furnham et al., 2014). Psychopathy is characterized by emotional insensitivity, impulsivity, antisocial behaviours, and an absence of guilt and empathy (Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

Correlations between the DT dimensions have been generally positive, ranging from .26 to .70 (e.g., Jakobwitz & Egan, 2006). Although the three constructs that make up the DT can be measured separately, instruments have been proposed that integrate them on a scale, such as the case of the Short Dark Triad (SD-3; Jones & Paulhus, 2014) (27 items) and the Dark Triad Dirty Dozen (DTDD; Jonason & Webster, 2010) with Portuguese validation (Pechorro, Jonason et al., 2019) (12 items). The DTDD, as a brief measure, offers more advantages for research. Among them are the fact that, when other evaluation measures are used, the response time of the participants is shorter, and therefore it has an impact on motivation and fatigue, especially in children and adolescents additionally, the brevity of the DTDD decreases the likelihood of missing items (Rammstedt & Beierlein, 2014).

Some authors have suggested that the DT may have an adaptive role. Although their characteristics are undesirable in cultures that favour cooperation between individuals, they may in the past have contributed to individuals’ survival in different situations of competition (Filho et al., 2012; Jonason & Webster, 2010). At present, competitiveness in the “working world” may increase the number of individuals with DT traits in the United States (USA), Western Europe, and Australia (Jonason et al., 2012). The characteristics of the DT can promote dysfunctional interpersonal relationships where emotional insensitivity may occur along with an absence of empathy (Lyons, 2019), manipulation (Jones & Paulhus, 2014; Lee & Ashton, 2014; Lyons, 2019), aggressive behaviours (Jones & Paulhus, 2014; Paulhus et al., 2002), contempt for social norms associated with significant damage or the exploitation of the other (Furnham et al., 2013; Lee & Ashton, 2014; Lyons, 2019) and impulsivity (Crysel et al., 2013; Jonason & Webster, 2010).

For James and colleagues (2014) there is a strong positive correlation between the scores of the DT trait and sensational interests (violence, weapons, and crimes), these being considered predictors of criminal behaviour. Some studies have shown significant associations between the three DT constructs and high scores of aggression and low empathy (Jonason & Webster, 2012; Munro et al., 2005); however, higher scores on empathy can be found in machiavellianism and narcissism, when compared to psychopathy (Rauthmann, 2012). When traces of the DT were verified in adolescents and young adults responsible for violent crimes in the USA and Europe, evidence was presented that they may have relevance in the aetiology of antisocial and delinquent behaviour (James et al., 2014). Boduszek et al. (2019), when comparing a sample of prisoners (n=772) with non-forensic samples from adults in the community (n=1201), university students (n=2080) and adolescents (n=472), suggested that previous studies may have overestimated the prevalence of psychopathy in forensic populations due to the inclusion of criminal behaviour items in the assessment of psychopathy.

In a study by Palma, Pechorro, Nunes, Correia and colleagues (2020), the authors concluded that the psychopathy dimension of the DT was the one that made the greatest contribution to the prediction of impulsivity. The machiavellian dimension also made its contribution, although considerably less. The contribution of the narcissism dimension was not significant. They also concluded that the psychopathy dimension of the DT was the one that made the greatest contribution to the prediction of conduct disorder (CD). The machiavellian dimension also made its contribution, although considerably less. The contribution of the narcissism dimension was not significant. Finally, they concluded that the male forensic group had higher scores than the male and female school groups and that, the male school group had higher scores than the female school group of traits of the DT, impulsivity, and CD.

Juvenile delinquency is related to behaviors, through which the individual expresses his rupture with the values of society (Poiares, 2016), qualified by criminal law as crimes (Rijo et al., 2016). The Educational Guardian Law (LTE) it is the most visible face of Portuguese juvenile justice that aims at “education for the law”, for learning and respect for the fundamental values of society (Negreiros, 2015). In adolescence the individual seeks his own identity (Campos, 2007), in this search, there may be conflicting behaviors with authority figures (Martinho, 2010). At this stage of development, the individual may not be aware of the relationship between a behavior and its consequences. This inability can make you vulnerable to the pressures to take risky behaviors (Organização Mundial da Saúde [OMS], 2020). There are risk factors that can enhance the development of juvenile delinquency (e.g., school absenteeism) (Farrington, 2005). When the families of these young people have a low socio-economic level (NSE), low level of parental supervision, they are more vulnerable to the influence of groups of deviant peers (Farrington, 2005; Lemos, 2010). Explanatory factors are also considered impulsivity, family members who exhibit antisocial and delinquent behaviors (Farrington, 2005), physical, psychological and sexual abuse (Brenda, 2005). For Morgado and Dias (2017) the most mentioned risk factors in studies on juvenile delinquency are the relationships and family support in which, the low level of parental supervision has proved to be a strong predictor of juvenile crime.

There has been a decrease in juvenile delinquency in most Western countries (Aebi et al., 2017). Regarding admissions to an Educational Center (CE) of the General Directorate of Reinsertion and Prison Services (DGRSP), the most serious of the educational guardianship measures foreseen in the LTE, in the year of 2018 there was an increase of 10.21% when compared to those of 2017 (Pechorro et al., in press). This increase is in line with official data released internationally, where Portugal remains one of the countries in Europe with the highest rate of juvenile prisoners per 100.000 inhabitants (Aebi et al., 2017; Souverein et al., 2019).

The main characteristic of Conduct Disorder (CD) it is “a pattern of repetitive and intermittent behavior in which the basic rights of others or the main social norms/rules corresponding to the age of the individual are violated” (APA, 2014, p. 566). The first significant symptoms of CD usually occur between the second childhood and the middle of adolescence, being more frequent in males (APA, 2014). The change in the diagnosis of CD in the DSM-5, which includes a specifier of emotional insensitivity traits (e.g., lack of remorse or guilt, indifference-lack of empathy), which are characteristics of psychopathy, has revealed the growing importance given to this construct (Frick & Moffitt, 2010; Scheepers et al., 2011). There is evidence that this may be associated with a greater stability of antisocial behaviour, serious and violent delinquent behaviour, early initiation of criminal activities, early detention, and convictions (Pechorro, Gonçalves et al., 2014).

Mistreatment of children and young people is related to “any non-accidental action or omission, perpetrated by parents, caregivers or others, that threatens the victim’s safety, dignity and biopsychosocial and affective development” (Direção-Geral da Saúde [DGS], 2011, p. 7). Child and juvenile abuse increases the risk of delinquent behavior (McCollister et al., 2010). Fox et al. (2015) when analyzing the impact of trauma in childhood on the increased risk of severe and chronic delinquent behaviors, they concluded that, a child exposed to adverse situations, such as abuse and/or neglect are more likely to exhibit severe, chronic and violent delinquent behavior by about 35%. In the same sense, the meta-analysis of Braga et al. (2017) suggests that all types of abuse are risk factors for violent antisocial behavior. There are several studies that have demonstrated that childhood exposure to adverse situations is associated with an increased risk of violent and antisocial behaviours, delinquency, and trauma prevalence in young people (Foa et al., 2018). Psychopaths may have been exposed to adverse childhood situations (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse) (Hodges et al., 2013); however, when this exposure is associated with the development of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), associations between narcissism and PTSD are established (North et al., 2012).

For Bachar, Hadar, and Shalev (2005), individuals who have been exposed to Potentially Traumatic Events (PTE’s) and have narcissistic traits can develop PTSD. In the same vein are the results obtained by Russ and colleagues (2008) in the USA. Using a national sample of individuals who were exposed to PTE’s, evaluated by mental health specialists (psychiatrists and clinical psychologists), they concluded that people diagnosed with Narcissistic Personality Disorder had higher PTSD scores.

The present study is a response to three considerations: the study of the DT may be relevant to understanding some frequently observed youth behaviours (e.g., antisocial, criminal) (Lyons & Jonason, 2015); aversive personality traits have only recently aroused researchers’ interest as a group of factors that should be studied together (Furnham et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2014; Lyons, 2019); and the constructs in question are particularly relevant for understanding the adaptation of adolescents to the community where they are living and have a strong impact. The present study will make an innovative contribution to the field, as no other study has looked at both male and female Portugese adolescents in a forensic and school context. The aim of this study was to analyse the associations of the DT dimension with juvenile delinquency, CD, and trauma. We pose three hypotheses: (1) the psychopathy dimension of the DT is the one with the greatest association with juvenile delinquency; (2) the psychopathy dimension of the DT is the one with the greatest association with CD; and (3) the narcissism dimension of the DT is the one with the greatest association with trauma.

Method

Participants

The total sample was composed of 601 participants (M age=15.95 years; SD=1.05 years; range=13-18 years), subdivided into a male forensic group (n=131; M age=16.09 years; SD=1.14 years; range=13-18 years), male school group (n=257; M age=15.97 years; SD=.98 years; range=14-18 years) and female school group (n=213; M age=15.75 years; SD=1.07 years; range=14-18 years). The participants who constituted the male forensic group were detained at the national level in the Educational Centres (EC) of the General Directorate of Reinsertion and Prison Services (GDRPS), to whom the tutelary-educational measure of internment was applied by the court. The participants who formed the male and female school groups were attending basic or secondary education in public schools in the Algarve, Alentejo and Greater Lisbon regions.

Instruments

The Dirty Dozen (DD; Jonason & Webster, 2010) is a short self-report measure of 12 items, designed to evaluate DT traits and comprising of three subscales: machiavellianism (e.g., I have used deceit or lied to get my way), narcissism (e.g., I tend to want other to admire me), and psychopathy (e.g., I tend to lack remorse). Each item is scored on an ordinal 5-point scale (1=never/almost never; 2=a few times; 3=sometimes; 4=often; 5=almost always/always). Higher values reflect the presence of higher levels of DT traits. In the present investigation, we used the Portuguese validation of the DD (Pechorro, Jonason et al., 2019) having been obtained in the present study an internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha of .86 in the Machiavellianism dimension, .94 in the narcissism dimension, .86 in the psychopathy dimension, and .93 in the total DD.

The Add Health Self-Report Delinquency (AHSRD; Udry, 2003) was developed for the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a prospective study of American adolescents from the seventh to the twelfth year of schooling. The scale is scored by adding the 10 items of the Nonviolent Factor (e.g., you took things from a store without paying) and the seven items of the Violent Factor (e.g., you pulled a knife or weapon to threaten someone), considering an ordinal 5-point scale (0=never/almost never; 1=a few times; 2=sometimes; 3=many times; 4=almost always/always). Higher scores indicate higher levels of juvenile delinquency. In this investigation the Portuguese AHSRD validation (Pechorro, Moreira et al., 2019) having been obtained in the present study an internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha of .96.

The Conduct Disorder Screener of the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (OADP-CDS; Lewinsohn et al., 2000) is a brief self-report measure of six items, designed to assess CD in adolescents. The scale can be scored by adding the items (1 - I broke rules at home, 2 - I broke rules at school, 3 - I got into fights, 4 - I skipped school, 5 - I ran away from home, 6 - I got into trouble for lying or stealing) on a 4-point scale (1=never/almost never; 2=sometimes; 3=many times; 4=almost always/always). Higher results indicate higher levels of conduct disorder. In the present investigation we used a Portuguese validation of CDS (Palma et al., submitted) having been obtained in the present study an internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha of .91.

The Child Trauma Screen (CTS; Lang & Connel, 2017) is a brief self-report measure for children and youth, consisting of 10 items. It is composed of two distinct dimensions where a total CTS value is not obtained. The first dimension is “Events”, which is related to exposure to Potentially Traumatic Events (PTE’s) (e.g., Has someone ever really hurt you? Hit, punched, or kicked you really hard with hands, belts, or other objects, or tried to shoot or stab you?), and is composed of four dichotomous items (1-4), and is coded (0=no; 1=yes). The sum of these items (Total Events), indicate the number of different types of potentially traumatic events experienced. The second dimension is “Reactions”, which is related to PTSD symptoms, consistent with the DSM-5 definition of PTSD (e.g., strong feelings in your body when you remember something that happened [sweating, heart beats fast, feel sick]). The Reactions dimension consists of six items (5-10) classified on a 4-point scale (0=never/rarely; 1=1-2 times per month; 2=1-2 times per week; 3=3 or more times per week) which, when added together provide the “Total Reactions”, where higher results indicate higher levels of PTSD. In the present study we use a Portuguese CTS validation (Palma, Pechorro, Nunes, & Jesus, 2020) having been obtained in the present study an internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha of .81.

The sociodemographic and criminal characteristics of the sample were collected through a sociodemographic and criminal questionnaire created for this study. The questionnaire collected sociodemographic information on each adolescent (e.g., age, sex, parental nationality, nationality and education of the participants, education, socioeconomic status, and marital status of the parents), as well as information related to criminality (e.g., problems with the law, age of the first problem with the law, kind of problem that occurred).

Procedures

The data collection from the male forensic group occurred after obtaining authorization for processing personal data from the National Data Protection Commission (NDPC) and data collection at the GDRPS EC’s. Data collection took place in all EC’s in Portugal. Before the battery of tests was applied in groups of three to six, each participant was given an informed consent form. The data collection of male and female school groups took place in Schools Groupings of the Algarve, Alentejo and Greatest Lisbon regions, after obtaining authorization for processing personal data from the NDPC and conducting a survey in the school environment of the General Directorate of Education (GDE) and respective directorates of public School Groupings. A free consent form was also signed by the students’ guardians, authorizing their participation in this study before the group test battery was applied. In all groups, cases where individuals were outside the pre-established age range (12-18 years) and where questionnaires were unusable (e.g., not completed, unreadable) were excluded. The participation rate was 90% and 92%, respectively.

Data analysis procedures

Data analysis employed IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v25 (IBM Corp, 2017). Data treatment was performed using ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis and Chi-squared tests to compare the groups under study when the variables were metric, ordinal, and nominal. The internal consistency was also analysed by Cronbach’s alpha, and Pearson correlations were used to analyse the associations between scalar variables and multiple linear regression models, to analyse the relationship between independent and dependent variables (Marôco, 2018). Regarding the magnitude of correlations, those between 0 and .20 were considered as weak, between .20 and .50 as moderate, and above .50 as strong (Ferguson, 2009). Internal consistency by Cronbach’s alpha between .60 and .69 was considered as marginally acceptable, above .70 as adequate, and above .80 as good (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Multiple linear regression models were performed to analyse the associations of the DT dimensions with juvenile delinquency, CD, and trauma. Correlations between independent variables, Tolerance, and VIF were analysed to diagnose multicollinearity. To analyse the quality of adjustment or as a measure of confidence in the regression model, the determination coefficient R 2 was used. This measures the proportion of the total variability that is explained by the regression model (0≤R 2 ≤1). It is a measure of the dimension of the effect of the independent variables on the dependent variable. A value of R 2 =0 indicates that the model does not fit the data. A value of R 2 =1 indicates a perfect fit. A value close to 0 indicates that the model is very inadequate, because much of the variability of the dependent variable is not explained by the independent variables. A value close to 1 indicates a very suitable model. An R 2 greater than >.50 is an indicator of a good fit. The part of the variability of the dependent variables that remained unexplained was due to other factors not considered in the regression model (Marôco, 2018). The results were considered significant for p<.05.

Results

The data revealed significant differences between the male forensic group and the male and female school groups regarding the completed years of schooling (F=273.38, p<.001; M forensic males=6.49, SD=1.42, range=4-10; M school males=8.98, SD=.95, range=7-11; M school females=8.92, SD=.95, range=7-11), socioeconomic level (SES) of the parents (KW=50.47, p<.001), and nationality (χ 2 =18.76, p=.00). The parents of the participants in the male forensic group had a lower SES. The male forensic group presented a greater diversity of nationalities than the male and female school groups.

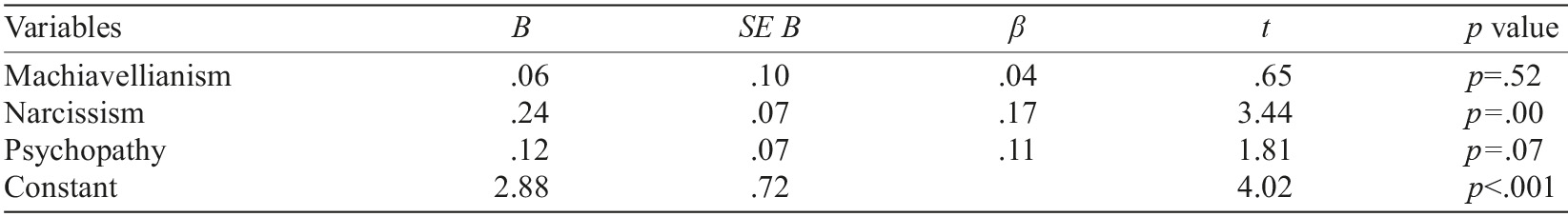

Table 1 shows the results of the associations between the variables within this study. The machiavellianism dimension was associated in a positive, strong, and statistically significant way with juvenile delinquency and conduct disorder and was positive, moderate, and statistically significant with trauma. The narcissism dimension showed a moderately positive, yet statistically significant association with juvenile delinquency, trauma, and CD. The psychopathy dimension showed a positive, strong, and statistically significant associated with juvenile delinquency and CD and showed a moderately positive and statistically significant associated with trauma. The results obtained revealed that the correlations between the independent variables of machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy were positive, strong, and statistically significant.

Table 1 Pearson correlation matrix between the variables under study

***Note. Juv delinq=Juvenile delinquency; Cond disorder=Conduct disorder; p<.001.

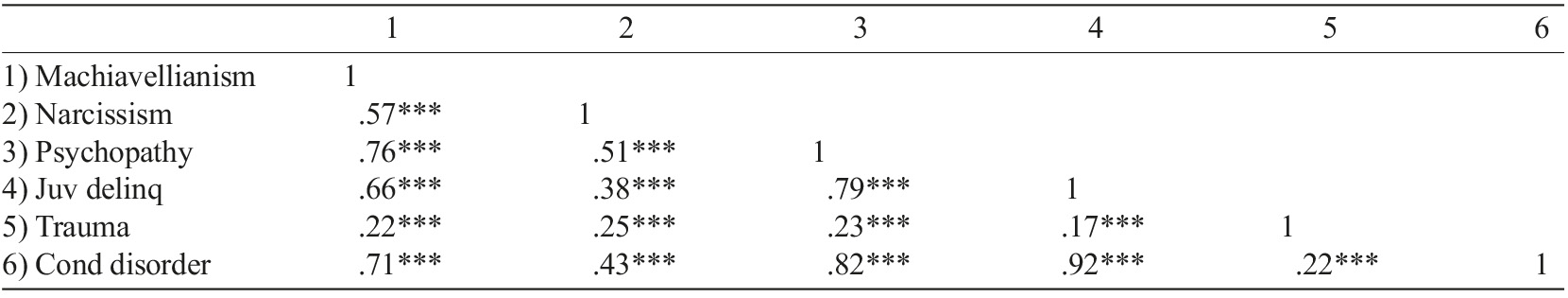

Considering the results of multiple regression for the DT in association with juvenile delinquency, it can be seen that the model is statistically significant. The R 2 value indicates that the proportion of the total variability of juvenile delinquency explained by the regression model is 64%. The determination coefficient (R 2 ) is an indicator of a good fit of the model to the data. The standardized regression coefficients (β) do not contribute equally to the model, presenting different magnitudes. The psychopathy dimension showed the greatest association with juvenile delinquency, whereas the machiavellianism and narcissism dimensions presented considerably smaller associations (see Table 2).

Table 2 Multiple regression analysis for the dimensions of the Dark Triad in association with juvenile delinquency

Note. R 2 =.64; F(3,596)=352.83, p<.001.

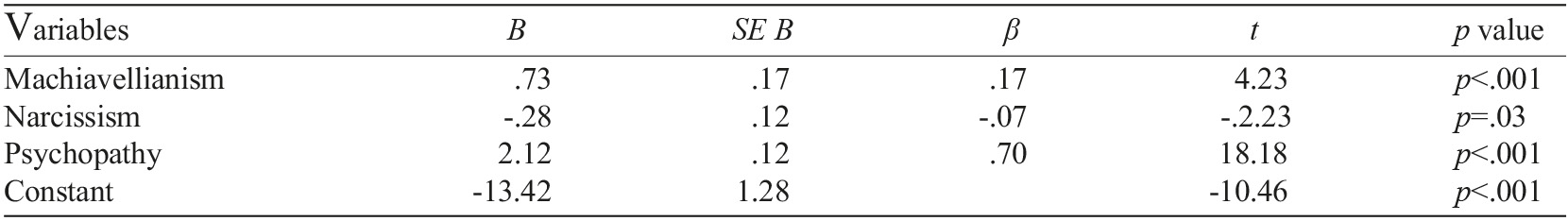

We can see that the results of multiple regression for the DT in association with CD are statistically significant. The R 2 value indicates that the proportion of the total variability of the conduct disorder explained by the multiple regression model is 70%. The coefficient of determination (R 2 ) is an indicator of a good fit of the model to the data. The standardized regression coefficients (β) did not contribute equally to the regression model. The psychopathy dimension is the one with the greatest association with conduct disorder. The machiavellianism dimension also has a significant association, although a considerably smaller one and the association of the narcissism dimension is not significant (see Table 3).

Table 3 Multiple regression analysis for the dimensions of the Dark Triad in association with conduct disorder

Note. R 2 =.70; F(3,596)=451.67, p<.001.

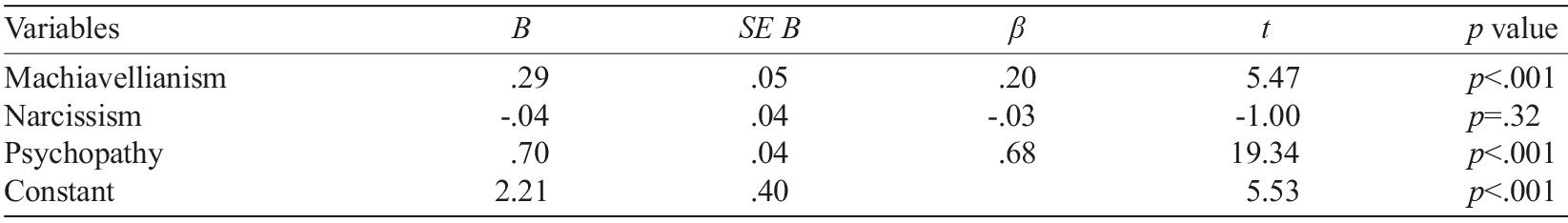

Regarding the results of multiple regression for the DT in association with trauma, it can be seen that the regression model is statistically significant. The R 2 value indicates that the proportion of the total trauma variability explained by the model is 8%. The coefficient of determination (R 2 ) is an indicator of a poor fit of the model to the data. The standardized regression coefficients (β) did not contribute equally to the regression model. The narcissism dimension is the one with the greatest association with trauma. The associations of the psychopathy and machiavellianism dimensions were not significant (see Table 4).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyse the associations of the DT dimensions with juvenile delinquency, CD, and trauma. We posited three hypotheses: (1) the psychopathy dimension of the DT is the one with the greatest association with juvenile delinquency; (2) the psychopathy dimension of the DT is the one with the greatest association with CD; and (3) the narcissism dimension of the DT is the one with the greatest association with trauma.

Considering the obtained results, the male forensic group had a lower number of years of schooling completed compared to the male and female school groups and also that the parents of the participants in the male forensic group had lower SES. For the authors consulted in the literature review, low education is positively associated with the practice of criminal activity. Absenteeism, dropout and school failure are considered risk factors for the development of juvenile delinquency (e.g., Carvalho, 2005; Farrington, 2005). Family characteristics should also be considered as predictive factors for delinquency. These youths may be inserted in families with low SES and with low level of parental supervision, being vulnerable to the influence of groups of deviant peers (e.g., Farrington, 2005; Lemos, 2010).

The results obtained also revealed that it was the psychopathy dimension of the DT that presented the greatest association with juvenile delinquency. These results are in line with our first hypothesis and are corroborated by previous studies consulted in the literature review. It should be noted that the construct of psychopathy applied to adolescents in the context of juvenile delinquency has, at present assumed an increasing importance in research, with several authors presenting evidence of its association with severe and violent delinquency (e.g., Pechorro, Marôco et al., 2014), and present psychopathy as a predictor of delinquency in youth within the general population (e.g., Marsee et al., 2005). In the present study, the machiavellianism and narcissism dimensions also presented an association with juvenile delinquency, although to a considerably smaller degree, corroborating the evidence from previous studies in which narcissism and machiavellianism would not independently contribute to delinquency. However, psychopathy is an independent predictor of delinquency among male adolescents (e.g., Chabrol et al., 2009). Accordingly, our first hypothesis was confirmed.

Considering the obtained results, it was the psychopathy dimension of the DT that showed the greatest association with CD. These results are in line with what we expected and are corroborated by other authors when they report that, in the DSM-5, youth with a diagnosis of CD present with behaviours similar to those of adults with psychopathy (e.g., Leistico et al., 2008), especially when they have limited prosocial emotions such as lack of guilt or remorse, or lack of empathy (e.g., Sylvers et al., 2011). It also has been reported in previous studies that there is evidence of retrospective links between psychopathy and CD in childhood (e.g., Sevecke & Kosson, 2010), and positive and significant correlations have been found between psychopathy and CD (e.g., Myers et al., 1995). Therefore, our second hypothesis has been confirmed.

Regarding our third hypothesis, this also aligned with the obtained results, since it is the narcissism dimension of the DT that has the greatest association with trauma. These results are also corroborated by the authors consulted in the literature review. In previous studies, child exposure to adverse situations has been reported to be associated with an increased risk of trauma prevalence in young people (e.g., Foa et al., 2018). It has also been reported that narcissism may be associated with PTSD symptomatology, when the individual was being exposed to potentially traumatic events in childhood (e.g., Bachar et al., 2005; North et al., 2012; Russ et al., 2008). Other authors have found positive associations between narcissism and PTSD symptomatology (e.g., Pietrzak et al., 2011). In the same vein are the results obtained by other authors, where they have concluded that people diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder may also have PTSD symptoms (e.g., Russ et al., 2008). Therefore, we can infer that our third hypothesis has also been confirmed.

Our study has some limitations. The fact that only self-response measures were used can be considered one of them. Therefore, in future studies, we also suggest the use of multiple assessment methods (e.g., rating scales), other informants (e.g., parents, teachers), and other sources of information (e.g., institutional information from education centres and schools). Although it has been reported by various authors that juvenile delinquency is more concentrated in young males (e.g., Hawkins et al., 1998), the absence of a female forensic group is another limitation of this study. However, the female forensic group to comply with educational guardianship measures in the EC’s of the DGRSP had a reduced dimension (n=22) when compared to the size of the other groups under study. Therefore, we chose to exclude it because it could statistically cause a confounding effect of sex. Boys have a higher number of behaviors with these characteristics and an equally higher frequency than girls (e.g., Moffitt et al., 2006). The self-reported delinquent behaviors by female individuals have a lower degree of severity and persistence and start in adolescence, therefore, they are considered late onset (Lanctôt & LeBlanc, 2002). The scarcity of studies on delinquent trajectories in female individuals can be partly attributed to the lower prevalence of their criminal activity when compared to that of boys, especially when referring to adolescents (Pechorro, 2013).

Within the scientific community there is a strong consensus on the need to identify, as early as possible, young people at risk of developing antisocial and delinquent behaviours or those who have already started a trajectory of transgression of the norms of the society where they are inserted, so that they can be referred to prevention and intervention programs (López-Romero et al., 2019; Rijo et al., 2017). Research in this area in the sense of real quantitative data (e.g., aetiology of phenomena, specific characteristics of young people) contributes to the effectiveness of prevention and intervention programs (e.g., psychotherapeutic, psychosocial), to improving knowledge about resistance to change and motivations for young people to abandon these programs (Monahan et al., 2009; Zara & Farrington, 2016), and reducing the costs of the programs to be implemented, because it allows a more judicious use of the available resources. This can be an important benefit, because the available resources are generally scarce (Pechorro, 2013, 2019; Polaschek, 2019). Prevention and intervention programs must involve the youths and those who interact with them (e.g., parents, teachers) (Cunneen & Luke, 2007).

Considering that juvenile delinquency can arise as a result of the rupture of social ties due to difficulty in integration (e.g., school, family) (Cusson, 2011) and that absenteeism and school dropout associated with young people with antisocial behaviors can occur as a result of several school failures and successive rejections by the peer group, difficulties in adapting to the school environment must be subject to preventive actions and early intervention to prevent the initiation of delinquent behaviors in adolescence (Rijo et al., 2017; Ryan et al., 2013). Students who are more engaged in school activities and who establish positive relationships with teachers are less likely to exhibit delinquent behaviors (Simões et al., 2008). Therefore, we hope that the present study can contribute to stimulate future research on the relationship between DT and juvenile delinquency, conduct disorder and trauma, as well as for the development and implementation of prevention and intervention programs aimed at youths with these characteristics.

Conclusion

We conclude that the psychopathy dimension of the Dark Triad is the one with the greatest association with juvenile delinquency. We also found the machiavellianism and narcissism dimensions to show an association with juvenile delinquency, although to a considerably smaller extent. We also conclude that the psychopathy dimension of the DT is the one we found to have the greatest association with conduct disorder. We found the machiavellianism dimension be associated with conduct disorder, although to a considerably smaller degree. And we found the association of the narcissism dimension to be not significant.

Finally, we conclude that the narcissism dimension of the DT is the one with the greatest association with trauma. Our results showed the association of the psychopathy and machiavellianism dimensions to not be significant.