Introduction

The spread of COVID-19 worldwide is affecting social organization and family routines. The overall lack of knowledge regarding transmission links, aligned with the non-specific symptoms of the disease at early stages and the ease transmission of the virus, lead to conventional containment on physical interactions as strategy across most of the countries (Wang et al., 2020), namely Portugal. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization estimates that around 1.38 billion children were out of school/child care, without access to group activities, team sports, or playgrounds due to COVID-19, as an emergency measure to prevent the spread of the disease (Cluver et al., 2020). Consequently, children and their families faced changes on daily routines. For many families worldwide arose the need to conciliate at home parents’ work and childcare demands, in which keeping child at home safe and occupied emerged as a force task for most of caregivers (Brooks et al., 2020; Coyne et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

The sudden changes on family and child daily routines, distant from other people, sources of support, and everything that used to be familiar, as well as the uncertainty related to the duration and consequences of this situation, may challenge both parents and child’s psychological well-being (Coyne et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). The interruption of regular activities outside home, namely the lack of in-person contacts with peers and teachers, physical activities, as well as negative feelings, such as the fear of infection or death, may decrease child’s social, emotional, and behavioral competence (Brooks et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). However, these negative feelings may be exacerbated for families living unemployment, from low-income, or living in crowded houses (Coyne et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020). This is critical because family’s ecological characteristics, namely social resources and the quality of interpersonal relations, play an important role on family members well-being (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006; Coyne et al., 2020).

The quality of interpersonal relations at home, namely parents’ marital adjustment, play an important role on child’s adjustment. Positive management of marital conflict elicits positive emotional reactions and behaviors from children, whereas negative forms may prompt their negative emotional and behavioral reactions (Camisasca et al., 2016; Cummings et al., 2003; Fosco & Grych, 2008). Importantly, parental competence and self-efficacy has been identified as an important aspect to family functioning, namely mediating family stress and child adjustment (Eldik et al., 2017; Jones & Prinz, 2005). Taking this into account, it is important to improve the understanding of these associations during challenging periods such this engendered by the pandemic situation of COVID-19. The current study aims to examine the direct effects of marital adjustment on child behavior and to test if parental self-efficacy mediated this association during home confinement due to COVID-19.

Influence of marital adjustment on child behavior

The quality of marital relationship is often described as the epicenter of family functioning and dynamics (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006; Cox & Paley, 2003). Marital adjustment is defined as a mutual process by which the partners develop gratification in the relationship, namely by the achievement of common goals (Heyman et al., 1994). Moreover, marital adjustment involves the ability to positively manage disagreements, relying on problem solving strategies and positive affections, which is related to better child’s behavioral and emotional adjustment (Cummings et al., 2003; Fosco & Grych, 2008). However, challenging situations such as the pandemic situation of COVID-19, may introduce disruption on marital adjustment, namely by economic instability, stress, lack of interpersonal trust and support (Cluver et al., 2020; Coyne et al., 2020), increasing conflict which may jeopardize child wellbeing.

Indeed, several studies have uncovered how children exposed to higher levels of marital conflict express worse socioemotional and behavioral development (Camisasca et al., 2016; Cummings et al., 2003; Fosco & Grych, 2008; Stroud et al., 2015). This association was conceptualized as the spillover effect, that is transference of affections, mood, and behavior to other interactions in the family system, such as parent-child (Cox et al., 2001).

Positive marital adjustment spills over to child interactions through positive affections and behaviors, such as positive mood, availability, greater engagement with children, which is related to greater socioemotional and behavioral adjustment of the child; whereas marital maladjustment spills over into interactions through anger, frustration, or distress, engendering more negative parental practices, resulting in more negative development of the child (Cummings et al., 2003; Fosco & Grych, 2008; Jones & Prinz, 2005). Although low marital adjustment is related to child’s behavioral problems (Camisasca et al., 2016; Cummings et al., 2003; Fosco & Grych, 2008), it is argued that these direct paths may be explained by other variables, such as parental competence or self-efficacy (Eldik et al., 2017; Fosco & Grych, 2008; Jones & Prinz, 2005). Thus, in this study, parental self-efficacy was examined as a potential mediator between marital adjustment and child socioemotional and behavioral development.

The mediating role of parental competence

The perception of parental competence or self-efficacy involves parent’s perception of ability to manage parental tasks, childrearing demands and positively influence child development (Coleman & Karraker, 1998; Jones & Prinz, 2005). These perceptions evolve over child development, according to child’s requests, parents’ ability to respond to child emotional needs, as well as to offer discipline and opportunities for new learnings (Ardelt & Eccles, 2001). However, self-efficacy perception relies on cultural and relational contexts and has been described as a key role on family functioning and child development (Coleman & Karraker, 1998; Eldik et al., 2017; Jones & Prinz, 2005).

Previous studies have uncovered how parental self-efficacy mediates parental aspects and child behavior (Eldik et al., 2017; Fosco & Grych, 2008; Jones & Prinz, 2005). On the one hand, marital adjustment has been found to be a predictor of parental self-efficacy (Eldik et al., 2017; Kwok et al., 2013; Suzuki, 2010). On the other hand, less marital adjustment has been related to increased socioemotional and behavioral problems of the child (Cummings et al., 2003; Fosco & Grych, 2008; Jones & Prinz, 2005). Parents with higher self-efficacy tend to use better strategies for communication and discipline, increasing the odds of child displays better outcomes on emotional, social, and behavioral domains (Ardelt & Eccles, 2001; Coleman & Karraker, 1998; Fosco & Grych, 2008).

These associations may be derived from the fact that marital conflict may limit parents’ judgments about their ability to manage parental duties, with negative consequences to child development (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006; Biehle & Mickelson, 2011; Eldik et al., 2017). This may be due to the distress related to marital maladjustment, engendering the perception of parents as less able to respond to the child needs, or perceiving the child as more difficult, offering less engaging behaviors, harsher discipline or indifference (Eldik et al., 2017). As a consequence, the child may exhibit lower socioemotional and behavioral adjustment (Baumrind et al., 2010; Costa et al., 2006; Denham et al., 2000). Based on that, we theorized that parental self-efficacy may explain why marital adjustment influences child socioemotional and behavioral outcomes.

Due to the pandemic situation of COVID-19, a high number of families are experiencing new daily routines, frequently with insecurities about the future, fear of contamination, and often with the need to conciliate their job demands and to support child’s care and homeschooling, which may challenge interpersonal relationships, influencing child’s emotions and behaviors. Aiming to better understand these association, the general goal of the current study is to examine the potential mediating role of parental efficacy between marital adjustment and child socioemotional and behavioral development in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, it will be examined the direct effects of marital adjustment on child affective, emotional, and behavioral development and to test if parental self-efficacy mediated this association during home confinement due to COVID-19.

Method

Participants

A sample of 163 children (73 girls; M age=6.09; SD=2.92; range: 2-12 years-old) and their caregivers (143 mothers; M age=38.69 years; SD=5.40; range: 27-51 years; 18 fathers; M age=44.50 years; SD=5.19; range: 37-54 years; and 2 stepmothers; M age=35.50 years; SD=7.78; range 30-41 years) were recruited online during home confinement, period decreed by the Portuguese government. Most of the mothers (96%) and fathers (99%) were married or lived with the children’s fathers/mothers. Couples had been married or living together for an average of 14 years (SD=5.77; range: 1-30 years). Around 90% of the mothers and 60% of the fathers had a university degree. Most of the participants (67%) lived in the two biggest metropolitan area of Oporto and Lisbon. Most of the participants and their children were in home confinement for on average 31 days (SD=12.08; children, M=33.85; SD=8.30; range: 0-60 days). Only 13 participants were not in home confinement, typically due to work reasons.

Measures

Marital satisfaction was measured with the Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick et al., 1998). The RAS is composed by 7 items (item examples: “How well does your partner meet your needs”; “In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship”) rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). Two items were reversed to create a total score of marital satisfaction. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was .70.

Child’s behavior was measured with the Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation Scale (SCBE; LaFreniere & Dumas, 1996). The SCBE is composed by 30 items and measures caregivers’ perceptions on the affective quality of a child’s relationships. It is organized in three subscales: anger-aggression, that assesses children’s angry, aggressive, and oppositional behaviors (10 items; item example: “Irritable, gets mad easily”, anxiety-withdrawal, that assesses children’s shy, anxious, and isolated behaviors (10 items; item example: “Remains apart, isolated from the group’”, and social competence, that assesses children’s positive social interaction and prosocial behavior (10 items; item example “Cooperates with other children”). Items are rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always). Cronbach’s alpha was .86 for anger-aggression, .81 for anxiety-withdrawal, and .73 for social competence.

Parental self-efficacy was measured with the Self-efficacy for Parenting Tasks Index - Toddler Scale (SEPTI-TS; Coleman & Karraker, 2003). The SEPTI-TS is composed by 53 items, that measures parental self-perceived competence in parenting. Items are rated on a 6-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). The SEPTI-TS has seven subscales (emotional availability, nurturance, protection, discipline, play, teach and instrumental care). Following the Portuguese validation of the scale (Ferreira et al., 2014) only 30 items five subscales (emotional availability, nurturance, discipline, play and teach) were used. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was .91 for the total score.

Procedure

Data were collected within the scope of a broader project that aims to understand the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on parenting and child adjustment. Overall, the project examined how psychosocial aspects of parents influenced family dynamics and wellbeing during the first Portuguese home confinement due to COVID-19: between March-June 2020. Specifically, the study examined sociodemographic aspects of the family (e.g., education, income, household composition), marital satisfaction and wellbeing, as well as child’s socioemotional behavior. All data was collected online and self-reported by one of the parents.

Participants were asked to report some information about their selves, the relationship, and the child; when there was more than one child in the household between 2-12 years-old, participants were asked to report information regarding the older child. This project was approved by the Ethical Committee of ISPA - Instituto Universitário. Parents’ were recruited during April 2020, using Qualtrics, hosted by ISPA - Instituto Universitário. All participants gave their informed consent to participate in the study after being informed about the purpose of the study described at the first page of the study.

Data analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS and AMOS (version 26; IBM, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to examine the relationships among marital satisfaction and child’s behavior (anger-aggression, anxiety-withdrawal, and social competence) and the proposed mediator parental self-efficacy. Number of days in quarantine was entered as covariate. Parents’ age, education, income, or child’s sex and age were not included in the model because preliminary analysis depicted non-significant correlations.

The maximum-likelihood robust estimation method was applied since variables were latent constructs (Gunzler et al., 2013). The adequacy of model fit was assessed using the following of goodness-of-fit indices: the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/df) (with values bellow 5 indicating good fit), the Bentler comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI; with values greater than .95 indicating good fit), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; with values smaller than .06 indicating good fit) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; with values smaller than .07 indicating good fit) (Hooper et al., 2008).

Direct and indirect effects using bootstrap resampling procedures was estimated to test mediation. Following the recommendations of MacKinnon et al. (2004), bias-corrected 90% confidence intervals (CI’s) for the unstandardized effects based on 5,000 resamples were used in the bootstrap analysis.

Results

Descriptive statistics

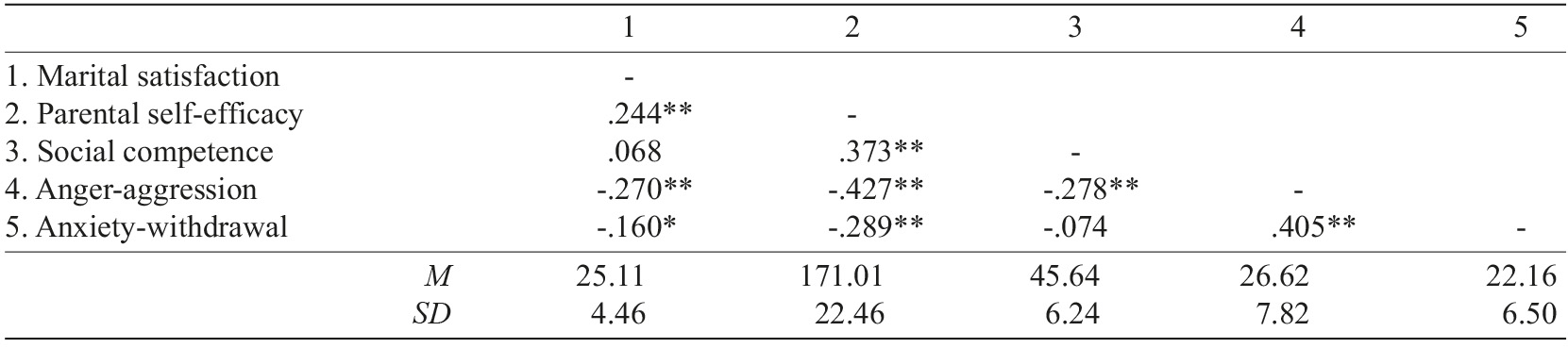

Descriptive analyses and bivariate correlations of the study variables are reported in Table 1. Marital satisfaction was positively associated with parent self-efficacy and negatively associated with child’s aggressiveness and loneliness. Parent self-efficacy was positively associated with child’s social competence and negatively associated with child’s aggressiveness and loneliness.

Mediation model

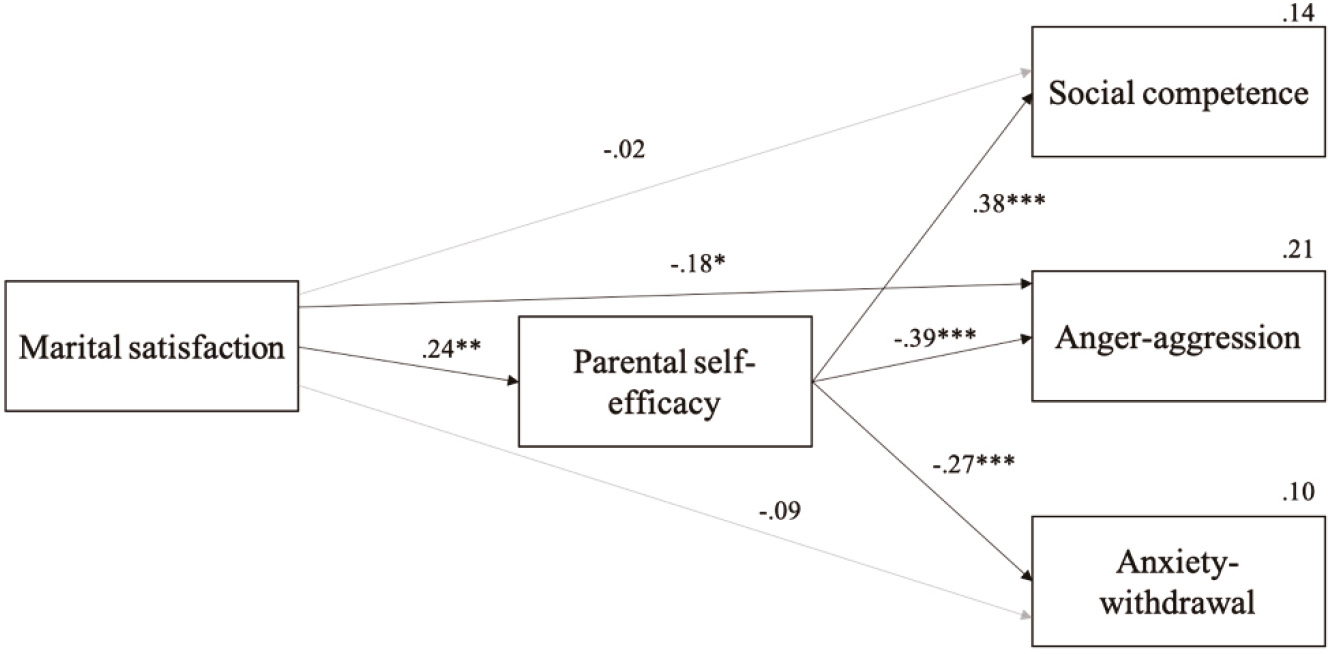

Figure 1 presents the significant standardized parameter estimates of the final mediational model. The model provided the following good fit indices: (χ² (2)=1.956; p=.376; χ²/df=0.98; CFI=.99; GFI=1.00; SRMR=.02; RMSEA=.00, p close=.510, 90% CI .000, .155) and accounted for 14%, 21% and 10% of the total variance in child’s social competence, anger-aggression and anxiety-withdrawal, respectively, controlling for the number of days in quarantine.

Figure 1. Structural equation model examining the mediating role of parental self-efficacy in the association between marital satisfaction and child’s behavior. Standardized coefficients are presented

In terms of direct effects, we found that marital satisfaction was positively associated with parental self-efficacy [r(161)=.24, p<.01] and negatively associated with anger-aggression [r(161)=-.27, p<.05], and that parental self-efficacy was positively associated with social competence [r(161)=.37, p<.001], and negatively associated with anger-aggression [r(161)=-.43, p<.001] and anxiety-withdrawal [r(161)=-.29, p<.001). Hence, greater marital satisfaction was related to lower aggression on children and to a greater socioemotional adjustment on children.

In terms of indirect effects, results of the bootstrap analyses showed that marital satisfaction was associated with child’s social competence, anger-aggression and anxiety-withdrawal through parental self-efficacy. Thus, higher marital satisfaction was associated with more parental self-efficacy which in turn was associated with children revealing more social competence (indirect effect=.093, SE=.04; p<.01, 90% CI .042, .172), and less anger-aggression (indirect effect=-.094, SE=.04; p<.01, 90% CI -.163, -.036) and less anxiety-withdrawal (indirect effect=-.067, SE=.03; p<.01, 90% CI -.122, -.024).

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine the mediating role of parental self-efficacy on the association between marital adjustment and child affective, emotional, and behavioral development in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. Findings highlighted the direct effects of marital adjustment to decrease child’s anger-aggression, i.e. greater marital adjustment was related to lower aggression on children. In addition, parental self-efficacy played a key-role in explaining the association between marital adjustment and child development, contributing to increase social competence, and decrease child’s aggressiveness and emotional withdrawn during this challenging situation.

These findings support the idea that family processes influence child’s wellbeing and development (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006), uncovering the importance of parents’ relationship on it (Camisasca et al., 2016; Eldik et al., 2017; Fosco & Grych, 2008). This information is particularly relevant in challenging periods such this of the pandemic situation of COVID-19, characterized by fear and uncertainty regarding the future. In addition, because parents and children tend to be at home during long periods with the absence of formal and informal sources of support and in charge of work and child demands, tensions and conflicts may increase disrupting family’s wellbeing and child behavior (Coyne et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Whereas previous studies have shown that longer periods of home confinement are related to worse psychological adjustment (Luo et al., 2020; Tull et al., 2020), our findings suggest that child’s psychological adjustment may not be affected by social longer periods of isolation when their parents are satisfied with their marital relationship and, consequently, feel more capable of performing their parental tasks. Hence, we may theorize about the importance of parental relations and competences to positively influence child adjustment, especially during challenging situations. It is important to note, however, that our data was collected when people were around 30 days at home. It is possibly that at this time both parents and children have already adjusted to the situation based on their (inter)personal resources. Marital adjustment, that is often described as the epicenter of family functioning, may contribute to influence individuals’ affections, mood and behaviors spilled-over family interaction, contributing to influence child development and well-being as found in previous studies (Camisasca et al., 2016; Cox & Paley, 2003). This pattern seems to occur also under challenging situations for families, such as the pandemic of COVID-19.

Our results also suggest that not only marital satisfaction, but also parental self-efficacy seem to have an important role on these adaptations, possibly due to the positive skills to solve problems and achieve adjusted goals and solutions (Cummings et al., 2003; Fosco & Grych, 2008). Because parental self-efficacy involves the ability to cultivate gratification in the relationship, namely by the achievement of common goals, it helps to decrease the negative effects of external situations and to promote child developmental adjustment (Camisasca et al., 2016; Cummings et al., 2003; Fosco & Grych, 2008). Findings support this perspective highlighting that greater parental efficacy was related to higher social competence and less aggression and anxiety-withdrawal on children. The mediating role of parental self-efficacy between marital adjustment and child behavior provides some evidence on how marital adjustment is important to influence parents’ perceptions about their skills to positively influence their children behavior and well-being (Coleman & Karraker, 1998; Eldik et al., 2017; Jones & Prinz, 2005). Previous studies depicted the association between marital adjustment and parental competence (Kwan et al., 2015; Kwok et al., 2013; Suzuki, 2010), which seems related to the confidence to manage external threats. Otherwise, parents with fewer perception of self-efficacy on parenting tasks deal with environmental challenges, with more uncertainty, distress and doubts on parenting (Eldik et al., 2017; Fosco & Grych, 2008; Jones & Prinz, 2005).

Findings uncover how interpersonal relations on family play a key-role on child’s well-being even during the environmental challenges such the pandemic situation of COVID-19. This result is possibly due to the fact that parents with better marital adjustment have higher skills to positively solve problems and disagreements, establishing reasonable alternative goals (Cummings et al., 2003; Fosco & Grych, 2008). This result, again, emphasizes the importance of interpersonal relations, namely marital adjustment to influence child well-being through parental self-efficacy.

Overall, this study adds to previous research by suggesting that ecological and interpersonal aspects play a key-role on people’s well-being, decreasing the negative effects of fear and uncertainty (Camisasca et al., 2016; Coyne et al., 2020; Cluver et al., 2020), even during stressful events, such as the pandemic situation of COVID-19. This is particularly relevant because most of the research has focused on individual consequences to mental health (Huang & Zhao, 2020; Tull et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), namely on a systematic review (Luo et al., 2020), leaving less clear the consequences to family relations, namely marital adjustment, perception of parental self-efficacy, or child’s development during this period.

Despite the social relevance of the findings some limitations of the current research must be addressed. First, participants’ recruitment was exclusively online with a high representation of highly educated middle-class families. In addition, we relied on a cross-sectional design. Hence, we are aware of limitations of these results to general population, particularly families living in low-socio-economic backgrounds. Second, most of answers were given only by one family member, typically the mother, limiting the perspective about other members of the family on these complex processes. Third, due to the recruitment procedures and the topic of the research, it is possible that only people more satisfied with marital relationship and with their parental roles have enrolled on research or those better adapted to the home confinement. Finally, self-report measures may have some biases on responses and may do not correspond to the reality of the families. Despite these limitations, we consider the findings are relevant to the current state of the art, given the lack of information surrounding COVID-19 and the consequences it may have not only to public health, but also to interpersonal relationships.