Introduction

In the working contexts of today’s organizations, characterized by complexity and uncertainty, and the consequent need for innovation and changes, the promotion of working characteristics and conditions that allow professionals to initiate changes on their one’s work by themselves - namely to have greater autonomy, flexibility and proactivity towards their work - is emerging. This new framework reality emphasizes the growing importance of recognizing the role of employees as having by themselves a proactive and active role in (re)designing their one’s jobs characteristics, roles and tasks at work (e.g., Bakker & Demerouti, 2014). The theoretical explanations regarding the job crafting concept will also be situated within the proactivity perspective on work redesign (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). In this sense, for Wrzesniewski and Dutton (2001), as founders of this concept, job crafting refers to initiatives made by professionals to redefine (or re-design) their roles, tasks and relationships in organizations, in a bottom-up perspective (Grant et al., 2010). Within the conceptualization of these authors, three forms of job crafting are described, which are: task crafting, relational crafting and cognitive crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Additionally, according to Tims and colleagues (2012), job crafting process refers to proactive behaviours of change, carried out by professionals in their work contexts, in order to balance the requirements of work tasks with the resources available to accomplish them, and with their capabilities and needs.

Furthermore, research has shown individual differences and context characteristics that are considered facilitators of the job crafting process (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). One line of literature approach, focusing on personal differences, has found that some features, namely “employees’ perception of proactive behaviour”; “self-efficacy” (e.g., Tims et al., 2014); “control over work contexts” (Kirkendall, 2013), “positive image perception towards work” and “need for connection with others” (e.g., Dutton et al., 2010), have potential implications for job crafting processes. Other approaches, that are focused on contextual features, found that some aspects such as employee’s “perception of promotion at work” (e.g., Wang et al., 2016); “supportive supervision” (e.g., Bakker et al., 2012), “job autonomy and social skill” (e.g., Sekiguchi et al., 2017); “level of freedom to carry out the job crafting process” and “reduced levels of interdependence in performing their jobs” (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001) are also determinants for the job crafting process.

The experience of organizational compassion has been recognized as having a key role in reducing employees’ suffering in their work contexts (Grant et al., 2008), as much as enhancing the capacity for operating in the workplace. In a recent study, Hur and colleagues (2017) demonstrated the mediation roles of “organizational identification” and “work engagement”, in the relationship between the perception of organizational virtues and job crafting. Hur and colleagues (2015) founded an effect of meaningful mediation of professionals’ creativity in their work context (customer services) on the relationship between compassion and work performance. Despite references to the positive effects of compassion at work (e.g., Lilius et al., 2008), few studies have empirically and accurately analysed how compassion influences (enhance) job crafting at the workplace and at the functional level of the members of the organization.

In order to fill these gaps in the literature, this paper aims to analyse the influence of professionals’ perceptions of compassionate behaviours in relation to their organizational environments. The core of this study is to analyse and test the relationship between the dimensions that constitute each of the constructs - that of organizational compassion and that of job crafting. We start by reviewing some of the definitions of organizational compassion and job crafting, and analyse their effects, alongside with the impact of the organizational compassion relationship on job crafting. Subsequently, we proceed to the analysis and test the hypotheses presented, and end up with major conclusions, research limitations, and future directions.

Theoretical framework

The Job Demands-Resources model. According to the theoretical Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), working conditions are classified into two general categories: job demands (require physical, social and organizational efforts and are related to physiological and psychological costs, such as fatigue) and job resources (foster personal growth, learning, development, and motivational qualities). Based on the JD-R model, Tims and Bakker (2010, p. 4) define job crafting as “the actual changes employees make in their level of job demands and job resources in order to align with their own abilities and preferences”. Furthermore, Tims and collaborators (2012) argue that the combination of high resources and demands perceived as challenges lead to high levels of motivation and engagement at work and high levels of performance. Moreover, based on the distinction between job demands and resources, Tims and colleagues (2012) classified job crafting into a four dimensions’ model: (a) “increasing structural job resources” (the development of the skills/abilities of professionals, the acquisition of new learning and the promotion of their autonomy at work); (b) “increasing social job resources” (to seek feedback and advice from colleagues and supervisors about their performance); (c) “increasing challenges job demands” (initiatives taken by professionals to engage in “extra” tasks, or new responsibilities, without expecting rewards, such as engaging in volunteer work or in new projects); and (d) “decreasing hindering job demands” (to minimize contact with “problematic” individuals, reduce overload and stress situations or avoid being involved in difficult decision-making processes).

Compassion at work: A dynamic interpersonal and social process. Based on the sociological theory, Dutton and colleagues (2014) defined compassion at work according to the sequentially developed interpersonal and dynamic theoretical model, with a two-way relationship between the four subprocesses: (a) “Consciousness of the suffering of the other” that occurs, in the work context, when the “focal actor” perceives and becomes aware of the suffering of the “sufferer”; this is an ambiguous process that requires constant observation, listening and seeking to understand the conditions, experiences or episodes of suffering, or circumstances of the “sufferer”; (b) “Empathy”, which is a feeling of empathic concern for the “focal actor”, and involves feelings of sympathy and altruism oriented towards the other, reflecting the motivation to help and alleviate his/her suffering; (c) “Evaluation” of the decision about whether the “compassionate act” makes sense, which is an interpersonal and evaluative dynamic cognitive process, both on the part of the “sufferer”, and in the search for understanding the situation (specific causes, merit and type of support) by the “focal actor”. This interpretation (to legitimate or not the compassion´s acts) is dependent on the type of judgments, expectations and perceptions present in the relational context, and established between “donor” (focal actor) and recipient (“sufferer”) at the moment of the suffering episode and is also related with the characteristics of the organizational context, such as the type of policies, culture, resources, leadership behaviours and organizational structures, and actions that can facilitate or hinder compassion (Simpson et al., 2014); (d) Compassionate “response type” which refers to the enactment of specific acts to reduce the suffering of others that can take a wide range of forms, such as gestures of emotional support, provision of material goods, flexibility at work, conversation, listening, and expression of empathy. Research supports the conclusion that there are organizational actions which facilitate the compassion process at work (e.g., “using communication channels to notify members of ways to help when someone is suffering”; “having programs that employees can access to support”), and also that communicate the value that responding someone’s suffering is important (e.g., Lilius et al., 2011).

Effects of organizational compassion on job crafting: Hypotheses. Emphasis was placed on the social identification of motivational theory principles (Tyler & Blader, 2003), on the perspective of reciprocity, and on the role of positive emotion theory (Rhee et al., 2006), addressed as mechanisms underlying the facilitation of involvement in job crafting behaviours.

The exposure to compassionate actions and experiences can positively influence individuals’ perceptions of their workplaces and lead them to display more dedicated and identifiable behaviours within the organization, thus shaping their tasks in line with the organization’s compassionate goals and values. In this regard, when professionals perceive their organization with optimistic, compassionate and honest values and attitudes (of respect, trust), they will tend to generalize such perceptions, both in their work and in their emotional and cognitive levels (Dutton et al., 2010). They will also tend to have more loyal attitudes, finding new meanings at work and experiencing a sense of mission (Wrzesniewski et al., 2013). Identification with the values of the organization may also enhance the development of efforts for professionals to redefine their tasks with similar meanings and purposes to those advocated by their organizations (Rego et al., 2011). At the same time, the perception of positive emotions in work contexts is associated with greater involvement and with initiatives by professionals (Parker & Griffin, 2011). In this respect, individuals involved in their work will identify a greater purpose in what they do, seeking to improve the characteristics of their work by redefining their tasks (Warr & Inceoglu, 2012). In organizations characterized by the expression of positive emotions, professionals perceive greater (intrinsic) motivation to deal with difficulties in their work, viewing errors as a learning opportunity and engaging in activities to redefine their work in order to give them a greater significance (Cameron et al., 2004). By perceiving supportive attitudes from their organization, from their leaders and co-workers, based on theoretical assumptions of reciprocal social exchanges (Blau, 1964), professionals will be more motivated to respond to one another by returning similar attentiveness behaviours, concern and care for others. They will thus develop pro-active behaviours and more commitment attitudes towards others which, in turn, may enhance the perception of their pro-social identity (Dutton et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2008). When they feel satisfaction and experience actions and a culture of reciprocity based on a relationship of social exchange with the organization, they will develop a stronger and more connected relationship with the organization and its members, and they will also tend to return similar care practices to others, making a greater commitment to work (Emerson, 1976). From the perspective of the positive emotions at work’s theory (Fredrickson, 1998), professionals who experience positive emotions in the workplace will be more receptive to new learning and also more prone to the development of their creativity (Boyatzis et al., 2013). In this respect, it has been shown, in previous studies (Talarico et al., 2009), that the expression and sharing of positive emotion narratives leads to greater cognitive and emotional openness of professionals, allowing them to reintegrate new ideas, learning to improve structural work resources and facilitating the compassionate interpersonal process. In a compassionate work engagement, people also become more confident about their decision-making autonomy and perceive greater connection with others that allows them to respond to situations of suffering with greater confidence and wisdom (Goetz et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2008). Additionally, with regard to the perception of identity to the organization (Lilius et al., 2011), professionals who experience compassion in organizations and who advocate compassionate practices may be more attentive, empathetic and will be receptive to peers, moreover supporting them in situations of suffering, and minimizing their distress and difficulties; in turn, this may potentiate “spirals of empathy”, generalizations of positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2003), and future pro-social behaviours. The process of increasing the social resources takes place in a compassionate relational context with implications: sufferers explicit their suffering and needs; “focal actors” strive to create greater psychological security for the expression of feelings; and both “sufferer” and “focal actor” can be involved in strengthening the quality of their bond (Wrzesniewski & Dutton 2001). Thus, individuals can redesign their own work to ensure that in their role are gathered resources to perceive, make sense and respond to suffering in the workplace. At an individual level, professionals who identify themselves with their organization in a positive manner will be also more motivated to engage in more voluntary commitments to colleagues who are suffering in the group, maintaining as well perceptions of self-worth and self-esteem. Tajfel (1974) argued that compassionate experiences among members tend to grow from the perspective of collective social identity, resulting in greater intrinsic motivation for involvement in job crafting behaviours and in greater work performance. Self-positive identity at work will foster their motivation for engaging in job crafting behaviours: they will feel more competent and they will tend to maintain a high perception of their self-worth and dedication to the organization (Dutton et al., 2010). Then, they will be motivated to engage in extra functions (roles) to help others in situations of difficulty or suffering. Through a context of self-esteem, support and encouragement among individuals, and a greater sharing of information, they develop intrinsic motivation which, therefore, facilitates their cognitive flexibility and involvement in new projects and challenges (Shalley et al., 2004). It is also noted that professionals with high perceived organizational identification believe that efforts to redefine their tasks and relationships are considered desirable from the perspective of their organization’s goals and values, anticipating their involvement in a larger number of (extra) tasks for shaping the work, so as to correspond to the alignment of these values (of trust, respect), according to which they feel integrated and to which they attribute meaning (Tyler & Blader, 2000). According to these assumptions, professionals who experience strong identification with the organization by experiencing compassionate practices in their workplaces are expected to be more receptive to include, voluntarily, challenging resources and compassionate behaviours in their roles, being more alert to recognize, empathize and minimize the suffering of others. Taking into account all these propositions and arguments, the following hypotheses are formulated in the first Model:

H1 a: Each of the dimensions of compassion process at work (namely (a) consciousness of suffering, (b) empathy, (c) evaluation and (d) response type) positively influence the “increasing structural job resources”; “increasing social job resources” and “increasing challenging job demands”;

H1 b: Each of the dimensions of compassion process at work (namely (a) consciousness of suffering, (b) empathy, (c) evaluation and (d) response type), negatively influences the “decreasing hindering job demands”.

Whenever individuals take active steps to alter or diminish tasks or job activities that are perceived as inconvenient they are decreasing the job demands perceived as obstacles (i.e., that hinder, obstruct or delay). This may be due to the tendency of workers to adjust work whenever it becomes more demanding (Clegg & Spencer, 2007). As noted in the paper of Sliter and colleagues (2012), professionals who experience compassion at work seem to be better qualified to deal with more emotionally and physically demanding work situations (stress situations, overwork, burnout, tension) and it is likely that the perception of compassion can attenuate these negative aspects by promoting positive emotions. Based on these assumptions, it is anticipated that the dimension of “decreasing hindering job demands” will be negatively related to the resources of compassionate organizational and interpersonal behaviours, which will play an important attenuating role for professionals to cope with more painful and emotional situations, and more demands at work perceived by them as obstacles. Taking into account all these propositions and arguments, the following hypotheses are formulated in the second Model:

H2 a: Each of compassionate “organizational actions” and compassionate “organizational characteristics” positively influence the “increasing structural job resources”; “increasing social job resources” and “increasing challenging job demands”;

H2 b: Each of the compassionate “organizational actions” and compassionate “organizational characteristics” negatively influences the pursuit of “decreasing hindering job demands”.

Method

Participants

The sample of participants who accessed the online platform was created through invitations (verbal, written, emailed, social networks, meetings) from a range of professionals, managers and organizations from different sectors (primary, secondary and tertiary). In addition to being a convenience sample, the snowball procedure (share and disseminate) was also used. Of the 419 participants who accessed the platform and who had, currently or in the past, a working status, only N=231 answered all the questions. Of the 231 respondents, 80% are currently employed, 12% are retired and 2% are unemployed. The number of female participants corresponds to 148 (64%) and of male participants to 83 (36%).The amplitude of age is between 22 and 84 years (M=48.8 years). Almost half (47%) has a college degree, 19.5% has a master’s degree and 4% completed elementary education (1st stage of formal education). Regarding history of the job function, 57.6% have been in the organization for over 10 years, and are working in the following most represented job sectors: 22.9% in education, 12% in health and 10.8% in public administration. Job activity is distributed between the public (42.6%) and private (37.8%) sectors, with a smallest representation of the non-governmental sector (16%). Weekly, the participants worked between 35 to 45 hours (58.4%); 45 hours or more (14.7%) and 25 to 34 hours (14.3%). Regarding the size of the work’s organization of the participants, data showed that the number of employees per organization was the following: 101 to 1000 (27%); 11 to 50 (21%); and 1001 to 5000 (14.7%). As to the size of their work teams, the most represented has 3 to 5 people (25.5%); 16 or more (24.7%) and 6 to 8 (20%).

Materials

Organizational Compassion: The “Organizational Compassion Questionnaire” used in the present study contains three scales included in the measure created by Simpson and Farr-Wharton (2017). In addition to the questions addressed to the four dimensions of the “Compassion at work Scale” (namely (a) Consciousness - 8 items; e.g., “when someone is suffering in my organization, others tend to… notice he signs”; (b) Evaluation - 9 items; e.g., “assess how deserving the co-worker is of compassion”; (c) Empathy - 8 items, e.g., “empathize”; (d) Response Type - 8 items, e.g., “take practical steps”), it includes one set of questions regarding the “Organizational Actions Scale” (8 items; e.g., “when someone is suffering in my organization, the organization tends to… provide a forum for expression concerns”) and one set of questions concerning the “Organizational Characteristics Scale” (6 items; e.g., “acts of compassion are common here”). The first 12 questions concerned the collection of participants’ socio-demographic and professional data. In parallel with the original study (Simpson & Farr-Wharton, 2017), which found adequate Cronbach’s values (0.93: Consciousness; 0.93: Evaluation; 0.94: Empathy; 0.95: Response type), the present study identified similar results in the four dimensions (0.93: Consciousness; 0.93: Evaluation; 0.94: Empathy; 0.95: Response type). Results for the other variables (0.94: “Organizational Actions”; 0.88: “Organizational Characteristics”) indicate that they adequately measure these two scales.

Job Crafting: The measurement of job crafting was based on the evaluation scale developed and validated by Tims and colleagues (2012). This scale consists of 21 items that are subdivided into four dimensions: (a) increasing structural job resources (e.g., “I try to learn new things at work”); (b) increasing social job resources (e.g., “I ask others for feedback on my work performance”); (c) increasing challenging job demands (e.g., “If there are new developments, I am one of the first to learn about them and to try them”); (d) decreasing hindering job demands (e.g., “I try to ensure that I do not have to make many difficult decisions at work”). In the original scale study (Tims et al., 2012), the Cronbach’s alpha values were adequate (0.75: “increasing job demands/challenge”; 0.82: “increasing structural job resources”), similar to those found in the Portuguese validation’s study (Esteves & Lopes, 2016), namely 0.72: “increasing challenging job demands”; 0.82: “increasing structural job resources”. In the present study those values were also consistent with the original study (0.91: “increasing structural job resources”; 0.82: “increasing social job resources”; 0.83: “increasing challenging job resources”; 0.87: “decreasing hindering job demands”). This shows that the variables adequately measure all the job crafting dimensions.

Procedures

The online questionnaire, which was used to collect the data for the present study, was drawn up by using the translated Portuguese version of the “organizational compassion scale” (Simpson & Farr-Wharton, 2017), made by the author and co-authors of the present study for this purpose and additionally, by using the “job crafting scale” (Tims et al., 2012) from the Portuguese version translated by Esteves and Lopes (2016). Subsequently, a pre-test was carried out, seeking to determine the suitability of the online platform and of the questionnaire to be applied, testing it with 3 experienced professionals. From 14th October 2017 to 28th April 2018, an online platform for data collection was set up. Participants were asked their level of agreement to each item’s statement using a six-point Likert scale (1: Strongly Disagree to 6: Strongly Agree).

Data analysis

For implementing the statistical procedures, which included descriptive statistics, correlations, and analysis of the relationship between the variables, the version 22.0 of the software SPSS was used. Additionally, Amos 22.0 was selected to implement the Confirmatory Factorial Analysis. To validate the scales, the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was first analysed as a model for checking internal consistency and validity of the scales (Hill & Hill, 2002). In order to analyse the effects of the dimensions of both constructs, the Structural Equation Model (SEM) was applied. Confirmatory Factor Analysis used the SEM (Kline, 1998). A reflective measurement model was used, where the causal relationship goes from the construct to the indicators. As for the estimation method used for the calculations, it uses the covariance matrix which consists of the maximum likelihood estimation method.

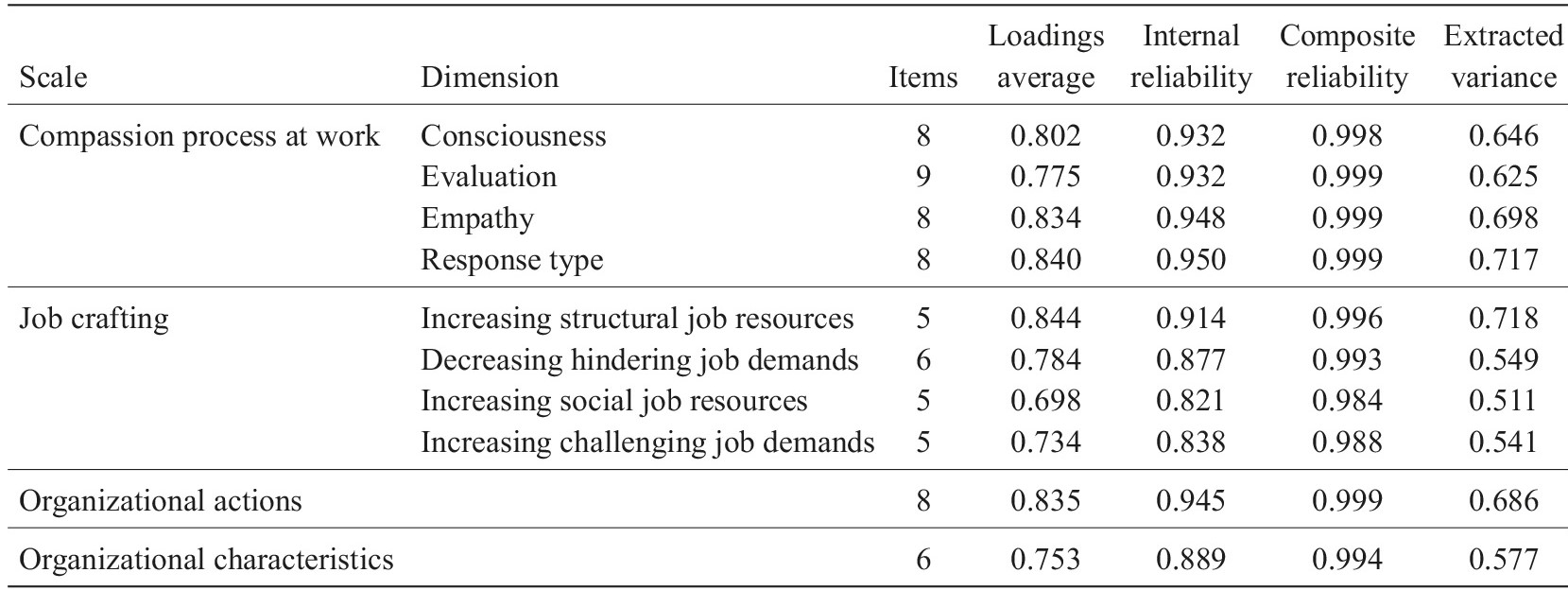

Confirmatory analysis of scales. Regarding the four scales, convergence validity (Table 1) was found for all dimensions of each scale. Therefore, convergence validity confirm the construction specified for these four scales. Therefore, we can conclude that the dimensions of the 4 scales are validated to measure the referred scales.

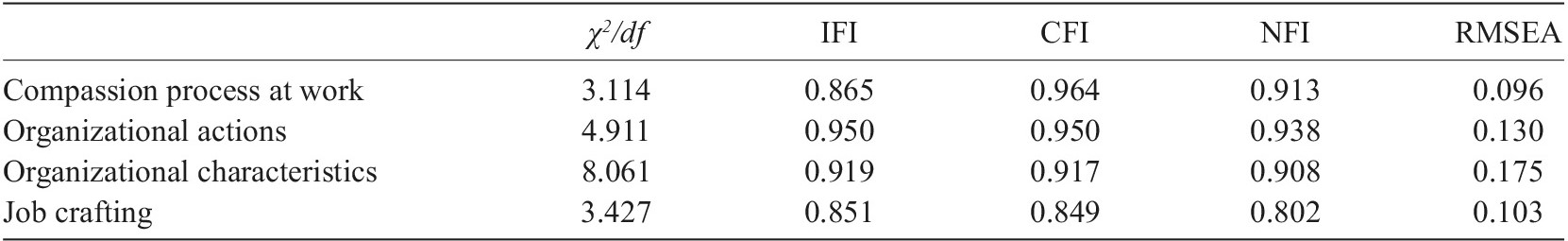

Additionally, taking into consideration the values of the adjustment indexes, we conclude that the psychometric indicators demonstrated the validity of the Portuguese version of the scales (Table 2).

Table 2 Analysis of the quality of the structural model adjustment to the scales

Note. Adapted by Arbuckle and Wothke (1999); Luque (2000).

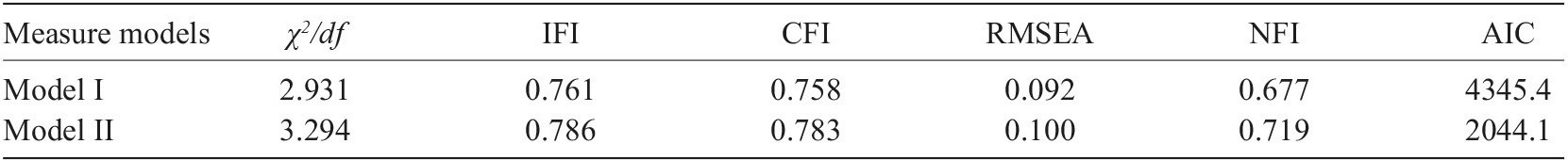

Test analysis of the hypothesis for the structural models I e II. The values for the saturation analysis and its statistical significance, for the overall structural model, reiterate the validation of each dimension, when taking into account the global model. In the two models, the measurement guaranteed an acceptable adjustment, although indicative of a poor overall adjustment of the proposed models (Table 3).

Table 3 Adjustment of the structural models

Note. Adapted from Arbuckle and Wothke (1999); Luque (2000).

Results

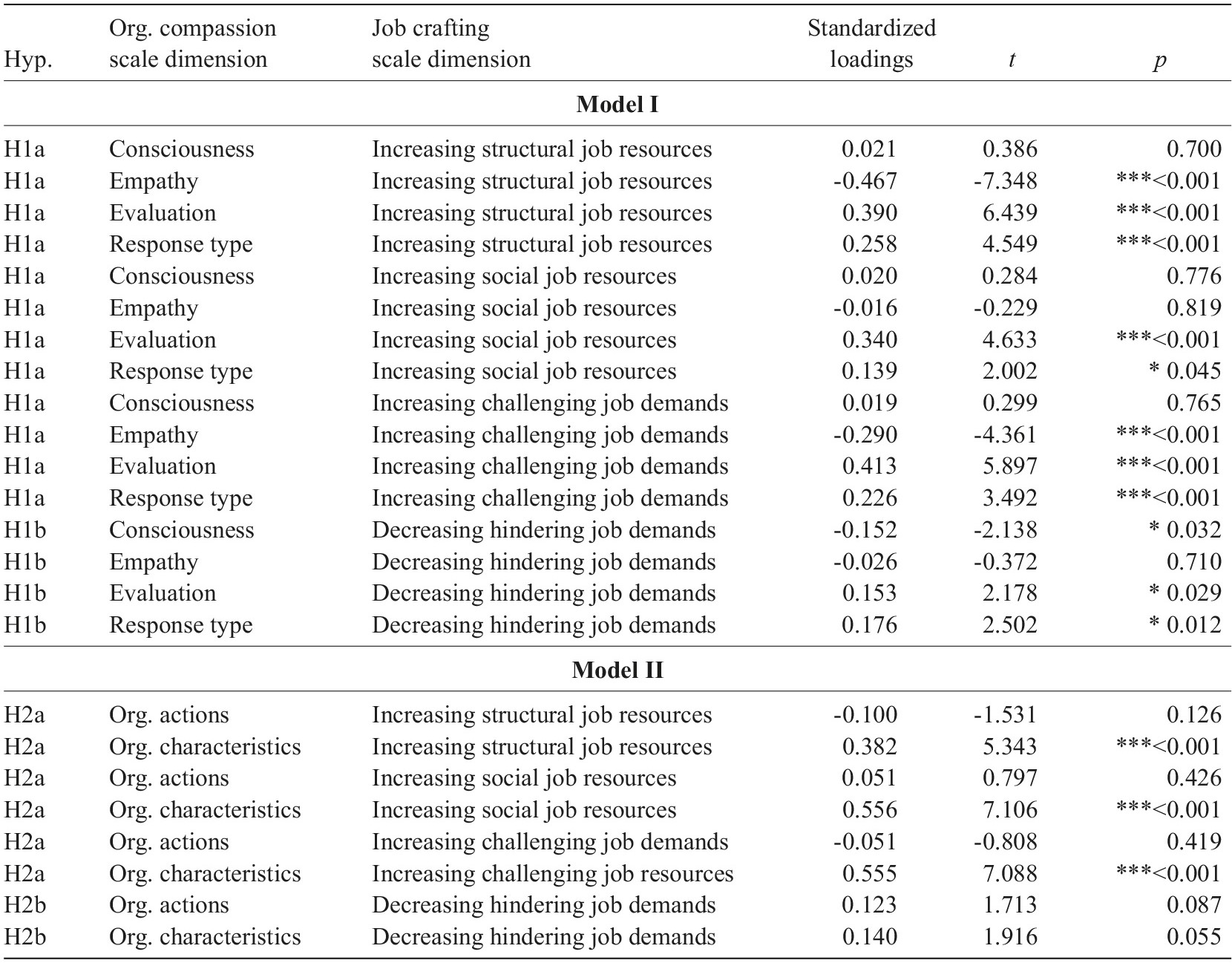

The results for the structural models (I and II), presented in Table 4, sanctioned the test of the four hypotheses (H1a, H1b and H2a, H2b) and the determination of the significant relationships among the different latent variables of the models.

Table 4 Structural models loadings analysis for hypothesis verification

Note. * p<0.05; *** p<0.001.

With regard to Model I, a significant positive effect of “evaluation” on “increasing structural job resources” was confirmed (β=0.390, p<0.001). H1a was also confirmed with a strong positive relational effect of “evaluation” on “increasing social job resources” (β=0.340, p<0.001). Furthermore, a significant positive effect of “evaluation” on “increasing challenges job demands” was also supported (β=0.413, p<0.001). H1a was also confirmed, with a strong positive statistical effect: firstly, of “response type” on “increasing structural job resources” (β=0.258, p<0.001); secondly, of “response type” on “increasing social job resources” (β=0.139, p=0.045); and thirdly, of “response type” on “increasing challenging job demands” (β=0.226, p<0.001).

Although results had showed a slightly positive standardized coefficient, the effects of these relationships were not statistically significant: firstly, of “consciousness” on “increasing structural job resources” (β=0.021, 1=0.700); secondly, of “consciousness” on “increasing social job resources” (β=0.020, p=0.776); thirdly, of “consciousness on “increasing challenging job demands” (β=0.019, p=0.765). Similarly, although the effects of the relationships had showed a slightly negative standardized coefficient, they were not statistically significant: firstly, of “empathy” on “increasing structural job resources” (β=-0.467, p<0.001); secondly, of “empathy” on “increasing social job resources” (β=-0.016, p=0.819); and thirdly, of “empathy” on “increasing challenging job demands” (β=-0.290, p<0.001). Therefore, these results allow to partially confirm H1a.

In testing H1b, first of all, a negative and statistically significant standardized coefficient was detected in the effect of “consciousness” on “decreasing hindering job demands” (β=-0.152, p=0.032). Secondly, a slightly negative standardized coefficient, not statistically significant, was identified on the effect of “empathy” on “decreasing hindering job demands” (β=-0.026, p=0.710). Thirdly, contrary to our predictions, the effect of “evaluation” on “decrease hindering job demands” (β=0.153, p=0.029) is positive and statistically significant. The effect of “response type” on “decreasing hindering job demands” (β=0.176, p=0.012) showed a positive and statistically significant standardized coefficient. These results indicate the rejection of H1b in Model I.

In regard to the analysis of Model II, H2a was confirmed with strong positive and statically significant effects: firstly, of “organizational characteristics” on “increasing structural job resources” (β=0.382, p<0.001); secondly, of “organizational characteristics” on “increasing social job resources” (β=0.556, p<0.001); thirdly, of “organizational characteristics” on “increasing challenging job demands” (β=0.555, p<0.001).

In face of the negative standardized coefficient, the effect of “organizational action” on “increasing structural job resources” was not statistically significant (β=-0.100, p=0.126). Similarity, although it showed a positive standardized coefficient, the effect of “organizational action” on “increasing social job resources” was not statistically significant (β=0.051, p=0.426). Furthermore, a non-significant statistical effect was verified for “organizational actions” on “increasing challenging job demands” (β=-0.051, p=0.419), although a negative standardized coefficient was present. Thus, the H2a was partially confirmed in Model II.

Concerning the analysis of H2b, although there was a positive standardized coefficient, the effects were not statistically significant: firstly, of “organizational actions” on “decreasing hindering job demands” (β=0.123, p=0.087); and secondly, of “organizational characteristics” on “decreasing hindering job demands” (β=0.140, p=0.055). Thus, H2b was rejected in Model II (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, four hypothesis were tested: firstly, in Model I, the predictive relationship between the organizational compassion dimensions and those of job crafting was analysed (H1a: each of the dimensions of compassion process at work - namely (a) consciousness of suffering, (b) empathy, (c) evaluation and (d) response type) positively influence the “increasing structural job resources”; “increasing social job resources” and “increasing challenging job demands”; H1b: Each of the dimensions of compassion process at work - namely (a) consciousness of suffering, (b) empathy, (c) evaluation and (d) response type, negatively influences the “decreasing hindering job demands”). Furthermore, in Model II, the predictive relationship between compassionate organizational and action characteristics and job crafting dimensions was analysed: H2a - Each of compassionate “organizational actions” and compassionate “organizational characteristics” positively influence the “increasing structural job resources”; “increasing social job resources” and “increasing challenging job demands”; H2b - Each of the compassionate “organizational actions” and compassionate “organizational characteristics” negatively influences the pursuit of “decreasing hindering job demands”).

Results demonstrate support for the positive impact of the relationship between the dimensions of compassion process that concern “evaluation” and “response type” on: “increasing structural job resources”, “increasing social job resources” and “increasing challenging job demands”. It was also demonstrated that the compassionate “organizational characteristics” enhance the job crafting mechanism, which will allow professionals to include all these compassionate resources when working with others and with their organization. One of the explanations for the lack of a positive relationship between the dimensions of “consciousness of suffering” and “empathy” on job crafting dimensions (“increasing structural job resources” “increasing social job resources” and “increasing challenging job demands”), may be the fact that, compared to the dimensions of “evaluation” and “response”, these variables (“consciousness” and “empathy”) do not imply an interpretation and direct action in order to minimize the other’s suffering experience. These three dimensions of job crafting of “increasing structural job resources”, “increasing social job resources” and “increasing challenging job demands” are similarly related to a proactive attitude that implies effort, stimulation and involvement. According to the interpersonal and dynamic model of the compassion process (Dutton et al., 2014), all the four dimensions are interrelated and part of the compassionate process. The process of assessing the meaning of the situation of suffering is carried out by the two parties involved in a given collective and individual context, whose interpretation will depend on the “empathy” established between them (focal actor and sufferer). Thus, the “awareness of the other’s suffering” is considered insufficient if “empathy” is not cultivated in the systems. Therefore, the cultivation of values and compassionate practices that facilitate this collective compassionate process (Simpson et al., 2014) is fundamental, the remaining dimensions being interrelated. The process of organizational compassion involves the understanding of the other person’s feelings in view of an empathic response, in order to minimize the other’s suffering. As previously addressed, “empathy” means the ability to identify with the other person and to be aware of what the other feel, and presupposes an understanding of their suffering (cognitive empathy), additionally requiring environments aligned with this culture in order to establish a climate of trust, communication and high cooperation. In fact, the importance of compassionate empathy is essential for dealing with compassion in a practical way in the world of organizations, and has been addressed in philosophical and sociological studies. For example, according to the empirical study developed by Simpson and Farr-Wharton (2017), the “empathy dimension” has a central mediating role in the relationship of awareness of the other’s suffering, the “evaluation” and the “compassionate response”. Contrary to expectations, there was no negative relationship between the dimensions of compassion process in “decreasing hindering job demands” and between compassionate “organizational characteristics and actions”, in “decreasing hindering job demands”. In this regard, neither the compassion process at work nor the compassionate characteristics and actions developed at workplaces (e.g., “existence of contingent plans to offer support”) seem to be sufficient for professionals to deal with the most painful demands or more stressful situations at work. Future studies should explore the reason why professionals who perceive compassion in their interpersonal relationships may prevent the development of efforts to reduce the demands of their work, with negative repercussions for them. In future studies, it is suggested to deepen the analysis of this relationship (between compassion and job crafting) with other variables (e.g., autonomy, perception of feedback, positive identification with work), which may strengthen the motivational resources to mitigate the need to seek to decrease those difficult or hindering demands. With regard to the influence of compassionate organizational actions, it was found that these did not relate to any dimensions of job crafting, a part from the compassionate organizational characteristics that related to all dimensions of job crafting, with the exception of the dimension of decreasing hindering job demands. In the context of organizations, institutional practices (actions) are inseparably involved with the organizational characteristics (e.g., Lilius et al., 2011; Madden et al., 2012), namely the values, culture and structure of the organization.

Limitations and future research

One of the limitations of the present study is related to the fact that the dimension of organizational compassion that relates to “evaluation” - and in what concerns the scale used in the present study (Simpson & Farr-Wharton, 2017) - only considers the perspective of the “focal actor” (donor). It should be noted that, in the “evaluation” dimension, the need to consider the point of view of the “recipient” (sufferer) as well had already been reported in previous studies (Simpson et al., 2014). In this respect, a reformulation of this aspect is suggested in future research, in order to include both perspectives. The way in which each person involved assess the meaning of the intentions and motivations of the other, and their relationship in the situation of compassion, is worth studying. Another limitation of this study was the fact that results were based merely on the answers given by the respondents from a specific cultural context and data was gathered from an online platform. In this regard, future studies might include a multicultural perspective and other methods for collecting data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study constitutes a contribution to the advancement of the literature, both on organizational compassion and job crafting. First of all, as an empirical study, it added knowledge regarding the characteristics of the compassion context at work that facilitate or constitute opportunities for the shaping of the work role. Specifically, it demonstrated an important relationship between the compassion dimensions of “evaluation” and “response” as facilitators in “increasing structural job resources”; “increasing social job resources” and “increasing challenges job demands”. It should also be stressed that the good psychometric qualities found in the validation of the instrument of organizational compassion (Simpson & Farr-Wharton, 2017), as applied to the Portuguese sample, may allow for its application in future empirical studies in Portuguese speaking countries relating compassion to other constructs (for example, leadership, organizational support, organizational citizenship behaviours, team work, well-being). It can also encourage attention to the topic of organizational compassion and broaden the reflection on the design of programs and management models intended to promoting compassionate organizational environments. In practical terms, it might also enhance awareness on the politics and practices of compassion at work, so that managers give greater consideration to the provision of resources for promoting compassionate practices in their organizations, aligned with organizational cultures in view of guaranteeing opportunities for professionals to engage in job crafting behaviours and to better humanize the current workplaces.