We are faced daily with various situations that we consider to be unfair and, in order to find an explanation that helps guide our future behaviors, we tend to attribute a sense of justice to these situations. The just world hypothesis is responsible for sustaining this motivation to seek justice (Lerner, 1980). The initial studies on this topic showed that people are motivated, even though unconsciously, to believe that the world is a fair place, and this phenomenon is metaphorically named Belief in a Just World (BJW) (Lerner, 1980). This concept was introduced by Melvin Lerner in the 1960s and has been extensively investigated ever since.

According to the initial research on BJW, believing that the world is a fair place allows individuals to understand their physical and social environment as safe, since it creates the illusion that the world is stable and orderly (Lerner, 1980). The first studies indicated that there would be a tendency in individuals to resort to mechanisms, or strategies, that tend to eliminate any type of threat to the BJW, such as injustice and the suffering of the victim. These strategies are associated with what is called by Rubin and Peplau (1973) secondary victimization, which happens when the victim, in addition to suffering misfortune, being a victim one time, will even be held responsible for the misfortune itself, being a victim for the second time. In this way, BJW would function as a personal contract, being essential for people to feel secure and optimistic about their future (Hafer & Sutton, 2016).

Lerner proposed that when this worldview is threatened, people need to cognitively restore justice. For example, people would blame innocent victims for their fate when they have no means of helping them (Landström et al., 2016; Vonderhaar & Carmody, 2015). Thus, the idea was established that individuals believe that people not only get what they deserve, but also deserve what they get (Lerner, 1980). Here it is important to note that these results have been confirmed in almost 40 years of investigations (Bartholomaeus & Strelan, 2019; Donat et al., 2018; Hafer & Sutton, 2016).

Measurement of BJW

The initial studies on BJW were developed based on an experimental paradigm (Lerner, 1965; Lerner & Simmons, 1966), that investigated mainly how people responded to situations that threatened the idea that the world is a fair place (Ellard et al., 2016). In the first experimental study conducted by Lerner (1965), participants were invited to judge the effort of two workers, who were confederates of the experimenter. They were informed that, due to lack of resources, only one of the two workers would be paid and that the selection of who would be paid would be random, and the result would be given to the workers at the end of the task. As a result, it was seen that the participants tended to more positively evaluate the effort of the worker who was paid, despite knowing that the pay was obtained randomly.

Whereas the study by Lerner and Simmons (1966) analyzed how people reacted regarding a situation in which a victim would receive electric shocks for having given wrong answers to some questions. In the first condition, participants could choose to transfer victims from a reward condition in which they would receive money instead of shocks. In the second condition, participants were informed that victims would continue to receive shocks for each wrong answer. Then, participants were asked to evaluate the victim. The results showed that the participants evaluated the victims more positively in the first condition. Based on these results, the authors proposed that this was happening as an attempt to avoid an experience of injustice, maintaining the belief that people have get they deserve (Lerner, 1965; Lerner & Simmons, 1966).

Subsequent studies suggested the possibility of BJW being a psychological disposition, considering that there are situational and individual variations in the perceptions of justice (Rubin & Peplau, 1975). The development of measures that assess individual differences in BJW has played an important role in advancing research in this area (Hafer & Sutton, 2016). As a result, there has been an increase in attempts to provide a reliable and valid measure of BJW, emphasizing the development and use of measures.

The first self-report measure that was proposed to assess individual differences of BJW was that of Rubin and Peplau (1973), the scale of belief in a just world (Just World Scale - JWS). It was initially composed of sixteen items, divided into two subscales: the belief in a just world (nine items) and an unjust world (seven items), of which thirteen were maintained. However, two years later, seven items were added and thus a revised version, consisting of twenty items, was developed (Rubin & Peplau, 1975). This measure became the most widely used for BJW and, despite criticism about its psychometric properties, is still widely used today (Hafer & Sutton, 2016).

The development of further measures took different directions. Initially, researchers created measures psychometrically more solid, based on criticisms about the weak psychometric properties of the Rubin and Peplau scale (Lipkus, 1991) and problems with the assumption of bipolarity, assuming that belief in a just and unjust world are different and relatively independent dimensions (Lipkus, 1991). Then the need also arose to distinguish the facets of BJW, with measures being developed to assess not only the idea of general BJW (Dalbert et al., 1987; Lipkus, 1991), but also of personal BJW (Dalbert, 1999). Personal BJW refers to the belief that events in each individual’s life are just; while General BJW exceeds the individual, portraying the belief that, in general, the world is a fair place (Dalbert, 1999). While personal BJW is positively associated with aspects of subjective well-being (Donat et al., 2016; Johnston et al., 2016), General BJW is positively correlated with anti-social tendencies (Hafer & Sutton, 2016).

The General BJW scale (General Just World Scale - GJWS) developed by Dalbert et al. (1987) was created in German and translated into English, and consists of six items combined in a single-factor structure (α=0.80). This measure was proposed as an alternative to the BJW scale of Rubin and Peplau (1975) and aimed to measure the degree to which the individual considers fair the events that occur in the world in general. Also aiming to provide a new scale that could be used as a viable alternative to that of Rubin and Peplau (1975), Lipkus (1991) developed a seven-item scale called the Global Belief in a Just World Scale that presented a single-factor solution (α=0.83). Later, Dalbert (1999) included seven more items to measure personal BJW, finding a single-factor solution (α=0.82). Thus, the new BJW Scale proposed by Dalbert totaled thirteen items that were theoretically distributed into two factors: personal and general BJW.

It is clear that the development of measures that assess individual differences in BJW plays an important role in advancing research in this area. However, the use of self-report instruments to measure BJW has been increasingly criticized in recent years. This has been happening due to the fact that BJW can be understood as a “preconscious” phenomenon (Lerner, 2003), that is, not fully accessible to consciousness. Thus, measuring BJW using scales would only assess the conscious dimension of BJW. Furthermore, the scale items are considered limited because they are influenced by social desirability, since the statements in the scales are considered counter-normative (Lerner, 2003).

In Brazil, a research program was carried out in which the Belief in a Just World Scale based on Popular Sayings (BJWPS) was developed. This scale is based on using popular sayings to measure individual differences in the belief in a just world (Linhares et al., 2022). In five studies, the authors confirmed the unidimensionality of the scale developed, as well as its good internal consistency, which proved to be compatible with or better than other measures widely used in the BJW literature.

The authors proposed that, when using popular sayings, individuals will have less resistance in expressing the idea that “the world is a just place to live”, since they will be confronted with popular sayings commonly used in their daily lives and are normatively supported. After conducting a literature search on popular sayings that might convey the idea that the world is a fair place, two new sayings that were not included in the original BJWPS. Therefore, the aim of this article is to validate a new version of BJWPS adding the two new-found items.

Overview

A research program was developed whose main objective is to demonstrate that a set of popular sayings express people’s motivation to believe in a just world. Our proposal is that, by using popular sayings as items to measure BJW, one can avoid responses tendentious to social desirability, or counter-normative ones, since individuals will be responding to statements that are used very often in their daily lives.

The results of two studies will be presented whose main objective was to validate a new version of the BJWPS (scale developed by the authors of this study, Linhares et al., 2022), proposing that this measure may be an alternative to the original scale initially proposed. For this, two studies were developed: Study 1 aimed to presenting psychometric evidence for a new version of the BJWPS scale through an exploratory factor analysis, and Study 2 aimed to verify the indexes of fit between the observed data and the proposed model.

STUDY 1

The intent of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of a revised version of the Belief in a Just Word Scale based on Popular Sayings (BJWPS) through analyses of its factor structure and consistency index.

Method

Participants

The participants consisted of a convenience sample of 160 university students from a public university in the city of João Pessoa, Brazil, of whom 84 of which were female and 76 were male. Participant ages ranged from 18 to 31 years, with a mean 21.29 years (SD=2.50). The sample included participants from physical education, pharmacy, nursing, nutrition, and electrical engineering programs.

Instruments

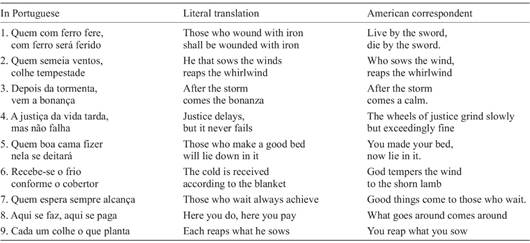

BJWPS Scale. Participants answered a questionnaire containing nine popular sayings, seven that constitute the original BJWPS and two more popular sayings that were added. The two new items added were: “What goes around comes around” and “You reap what you sow”, which, like the items of the BJWPS, also propose to assess the individual differences in the general BJW.

The participants’ task was to indicate how much they agreed with the content presented, ranging from 1=totally disagree to 5=totally agree, on a five-point Likert scale. It is noteworthy that the BJWPS does not use popular sayings specific to the Brazilian context, but rather uses popular sayings that carry the idea of justice in the world in their meanings, so as to test their use as an instrument for measuring BJW (Appendix 1).

Sociodemographic Questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of two closed questions related to their sex and age.

Procedures

Initially, it was necessary to contact the coordinators of the programs to request authorization to apply the questionnaires. Then, we directly contacted the professors in their classrooms, requesting the release of the students to answer the questionnaire. After signing the free and informed consent form, the participants were instructed to respond to the instrument individually.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21. The data were submitted to an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), using the principal axis method, without specifying the number of factors to be extracted. For factor retention, two criteria were used: (1) Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalue greater than 1); (2) Cattel’s criterion (graphic distribution of eigenvalues, screeplot). The internal consistency was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Descriptive statistics depicted participants’ sociodemographic information. A preliminary analysis on residuals estimates of each item indicated they did not differ from a normal shape distribution.

Results

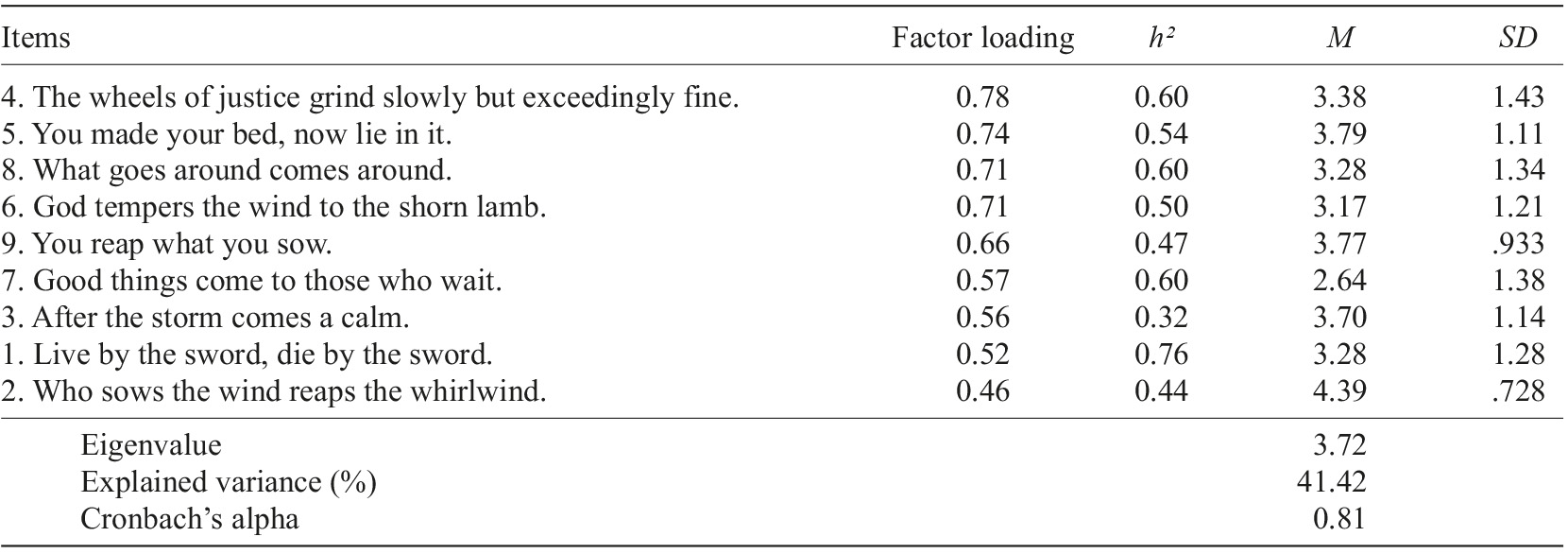

The adequacy of the sample was verified using the significant value of Bartlett’s test of sphericity, χ 2 (36)=397.80; p<0.001, and the KMO index (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin)=0.841. The results indicated the presence of only one factor underlying participants’ adherence to the nine sayings. This occurred using both the Kaiser and the Cattell criteria. The extracted factor had an eigenvalue of 3.72, explaining 41.42% of the total variance, and all items saturated satisfactorily, that is, greater than 0.40 (Table 1). In order to verify the structure and reliability of this scale, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated, resulting in an α=0.81.

In view of the results found, it is concluded that the objective of this study was achieved, since the scale presented satisfactory psychometric indexes of validity and precision. In order to verify if the single-factor model is really adequate, new analyses were carried out, as described below.

STUDY 2

The intent of this study was to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of revised version of the Belief in a Just Word Scale based on Popular Sayings (BJWPS), seeking to find more evidence to confirm the single-factor structure of the proposed new scale.

Method

Participants

The participants consisted of a convenience sample of 144 university students from public universities in the city of João Pessoa, Brazil, being 89 men and 55 women. Participant ages ranged from 19 to 30 years, with a mean 26.59 years (SD=11.40). The sample included participants from pharmacy, nursing, physics and Food Engineering programs.

Instruments

As in Study 1, participants indicated how much they agreed or disagreed with the content of the items (from 1=totally disagree to 5=totally agree).

Data analysis

To conduct the CFA, the AMOS 6 (Analysis of Moment Structures) software was chosen. To test the fit of the proposed model, the following indexes were analyzed: CFI (Comparative Fit Index), with a value ranging from 0 to 1, with values equal to or greater than 0.95 indicating a good fit of the proposed model; RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), values below 0.06 indicate good fit of the model; AGFI (Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index), with an acceptance value greater than or equal to 0.80 (Hair et al., 2009).

Results

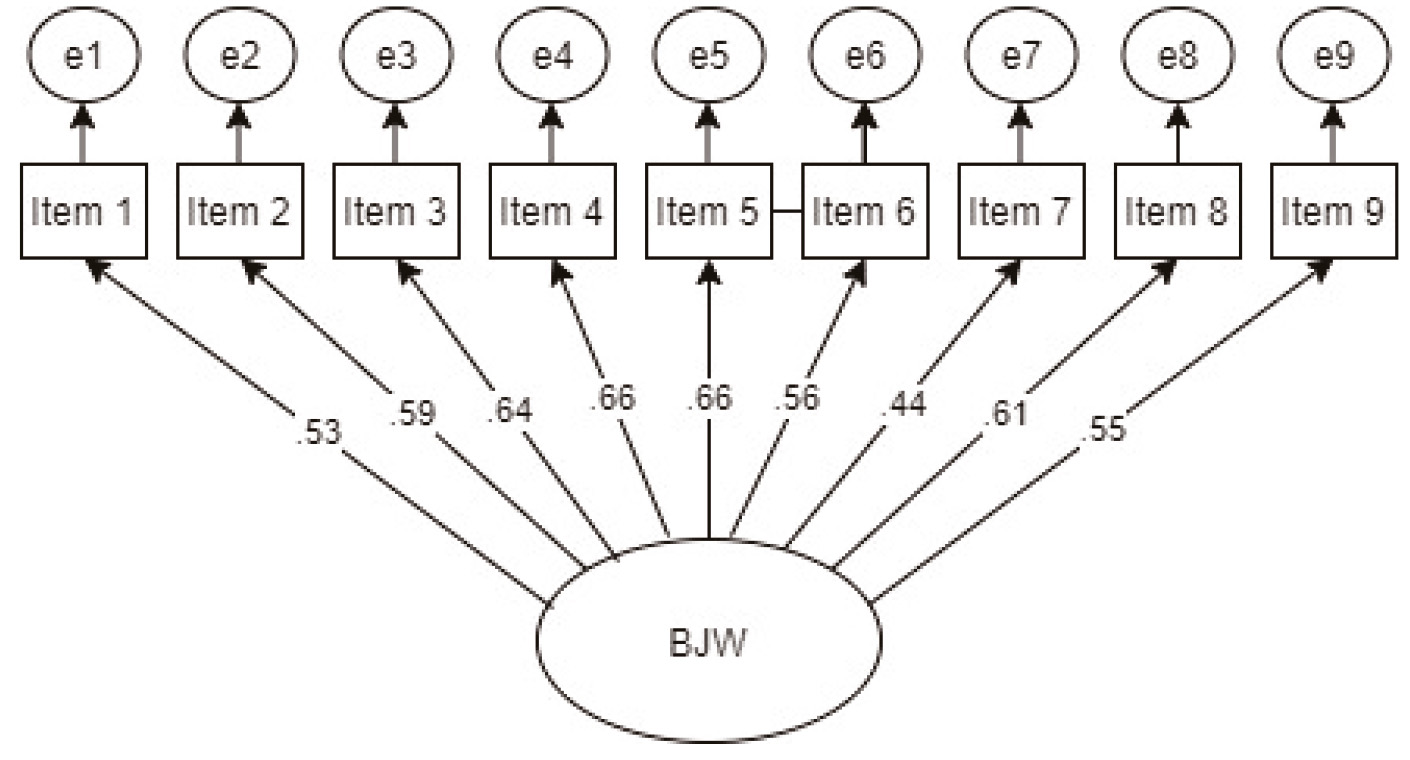

The indexes of fit indicate a good fit for the proposed model: χ 2 (df=12; N=241)=55.59; χ 2 /df=4.63, p=0.000; CFI=0.94; AGFI=0.96; RMSEA=0.04. It is noteworthy that no high correlations were observed between these residuals, as they are all below .10. Thus, the model’s quality of fit indicators can be considered satisfactory, confirming the single-factor model without the need to re-specify the model. Finally, the internal consistency of the scale proved again to be satisfactory (α=0.78). From the CFA (Figure 1), the single dimensionality of the BJWPS scale was evident, showing the quality of the model’s fit through satisfactory indexes as indicated by the literature (Hair et al., 2009).

General discussion

In this article, we presented the results of two studies that aimed to validate a new version of the BJWPS proposing that this measure may be an alternative to the original scale, a scale based on popular sayings to measure individual differences in the BJW. In Study 1, an exploratory factor analysis and internal consistency analysis were carried out in order to assess whether the psychometric estimates of the proposed new scale were satisfactory. In Study 2, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted, which showed a satisfactory goodness-of-fit of the proposed scale’s factor structure to measure the general BJW.

The results of the two studies indicated that the addition of the new items to the BJWPS satisfactorily contributes to the measurement of BJW through popular sayings, since the new version presented satisfactory factor loadings and internal consistency estimates. This instrument presented a single-factor structure that assesses individual differences in the general BJW, which is consistent with the theoretical frameworks of the BJW scales (Dalbert et al., 1987; Lipkus, 1991). The single-factor structure was confirmed by analyzing the criteria chosen to define the number of factors to be extracted (Kaiser criterion and Cattell criterion), as well as through confirmatory factor analysis. Finally, the internal consistency index (Cronbach’s alpha) of the new scale is in accordance with the acceptability criteria. Thus, the inclusion of these two new items into the BJWPS scale makes it a good alternative to the initial version.

In summary, these results contribute to and continue the line of research inaugurated by the studies developed by the authors of this study (Linhares et al., 2022), demonstrating the validity and reliability of the use of the popular sayings proposed to measure BJW. Results are also consistent with the idea that measuring psychological traits through sayings can bring to light individual differences in basic psychological motivations through a metaphorical language that expresses culturally shared and historically constructed knowledge. The development of a BJW scale based on popular sayings could represent an important contribution to the psychological assessment of people’s expression of the BJW, thus contributing to theorizing about the constituent elements of this motivation.

Final considerations

Validation of a new version of BJWPS with the inclusion of two new items can contribute to the literature on BJW measurement. The proposed new scale proved to be advantageous by being a brief and easy-to-apply measure because it uses a common and widely employed language in our country, and can be used in different contexts and cover the general population. The current research has the usual limitations inherent to the various studies on construction and validation of psychological instruments because they are based on specific sample student populations.

For upcoming studies, it is believed relevant to consider larger and more diversified samples, including people from different countries and cultures. We emphasize that, despite the satisfactory psychometric indexes, it is still necessary that the measure be adapted to other cultures and countries in order to have more evidence about its validity. It is also suggested to use this new CMJ measure in other studies, in order to take advantage of its effectiveness in measuring CMJ, correlating it with other constructs and, thus, contributing to the development of new knowledge in the area of social psychology.