Physical punishment can be defined as a parental practice that uses the physical force to cause bodily pain or discomfort to the child, with the aim of correcting the child’s misbehaviour (Gershoff, 2008). Research has consistently shown that physical punishment is a negative childhood experience that can be a source of toxic stress (Gershoff, 2016) and that negatively impacts children’s brain development, cognitive performance, and socioemotional adjustment (Cuartas et al., 2020; Gershoff et al., 2018; Heilmann et al., 2021; Salhi et al., 2021) but also increase the risk of developing later depressive symptoms, suicidal tendencies, and addictive behaviours (Gershoff et al., 2018).

Notwithstanding its negative consequences, about 4 in 5 children aged 2 to 14 years continue to experience physical punishment from their caregivers worldwide (United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF], 2017). In Portugal, the Law 59/2007 (Ministério da Justiça, 2007) has prohibited physical punishment against children. However, the number of crimes related to domestic violence against minors has increased 8.1% between 2012 and 2020 in our country (Sistema de Segurança Interna, 2021). Understanding the contextual factors that can predict the use of physical punishment is essential to prevent its occurrence and adverse developmental outcomes (Cuartas et al., 2019).

Drawing from the bioecological system framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), the process-context model, proposed by Gershoff (2002), acknowledges that contextual factors, comprising nested levels of influences, can serve as predictors of whether corporal punishment is used. According to this theoretical model (Gershoff, 2002), the most stable individual and relational context (i.e., characteristics of the child, household, and parents) is one of the contextual factors that can predict the frequency of use of physical punishment. With respect to children’s characteristics, research has shown that parents of younger children and boys were more likely to report the use of physical punishment than parents of adolescents and girls (Abdel-Fatah, 2021; Ward et al., 2021; Wissow, 2001). Increased stress-inducing factors in the household, such as low socioeconomic status or poverty, and a higher household size, have also emerged as predictors of the use of physical punishment (Abdel-Fatah, 2021; Cuartas et al., 2019; Beatriz & Salhi, 2019; Wissow, 2001; Ward et al., 2021).

Parents’ characteristics have been also found to predict the use of physical punishment. More specifically, studies have consistently shown that mothers (Nho & Seng, 2017; Ward et al., 2021) who were younger and had lower educational qualifications (Grogan-Kaylor et al., 2018) were more likely to use this disciplinary strategy when compared with fathers, older and more educated mothers. Physical punishment also appeared to be more common among single or divorced parents and caregivers who reported higher levels of conflict, discord, or unhappiness in their marital relationships (Abdel-Fatah, 2021; Gershoff, 2002; Ward et al., 2021). Parental beliefs about physical punishment, that is the set of cognitions that parents have about their children, what it is acceptable and how to take care of children (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Sigel et al., 1992), also emerged as significant predictors of the use of physical punishment practices. Several studies found that parents who believed that spanking is a useful disciplinary technique that teaches children how to behave and has positive effects were more likely to report the use of this parental practice (Bunting et al., 2010; Cappa & Khan, 2011; Durrant et al., 2003; Holden et al., 1995; Holden et al., 1999; Vittrup et al., 2006).

Despite its contribution for the current state-of-art knowledge, research to date has been mainly conducted in African and some Asian and South American countries (Abdel-Fatah, 2021; Cuartas et al., 2019; Cuartas et al., 2020; Jocson et al., 2012; Nho & Seng, 2017; Patias et al., 2012). The bioecological system framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006) acknowledges that culture and macro-time may influence parenting beliefs and practices, including those related to physical punishment. To our knowledge, the few studies that have examined parental reports of physical punishment and their correlates in Portugal have been essentially conducted before the legislation shift (e.g., Machado et al., 2003) and in specific areas of North of Portugal (e.g., Sani & Cunha, 2011).

The present study aimed to: (1) describe the maternal reports about the use of different physical punishment practices in the last year; and (2) to analyse the predictive role of children’s (sex and age), mother’s (age, education, perceived quality of the marital relationship and tolerance toward physical punishment) and household’s (socioeconomic status, household size, number of children) characteristics for the use of different physical punishment practices in the last year.

Method

Participants

The sample of the present study consisted of 289 mothers. The inclusion criterion was being a mother of a child aged 5 to 14 years. Mothers who reported that the child had a diagnosis of psychopathology, not being Portuguese and didn’t confirm their informed consent to participate were excluded from the study.

Mothers were aged, on average, 40 years old (SD=5.24). Most of them married or cohabiting (n=251, 87%), had a higher education level (n=218, 75%), and classified their socioeconomic status as medium (n=176, 71%). Most mothers were married/cohabitating (n=251, 87%) and perceived their relationship with their partner as highly positive (M=8.19, SD=1.36). Participants reported living, on average, with 3 persons (SD=0.99), and having, on average, 2 children (SD=0.71). Children were, on average, aged 8 years (SD=2.64) and 51% (n=148) were boys. Globally, mothers reported a low global acceptability toward physical punishment (M=30.35, SD=8.86).

Procedure

Data collection was carried out online, through the Qualtrics platform, between June and December 2021, using a convenience sampling method. The study was advertised by e-mail in the contact network of the research team and in social media (such as Instagram and Facebook), with a request to participate in the study. This advertisement provided a link to accede to an informed consent, explaining the study aims and procedures, the voluntary nature of the participation in the study and the confidentiality of the responses. Participants who agreed with the terms of informed consent were able to accede to questionnaires and to complete them in the Qualtrics platform.

Measures

Sociodemographic form. The sociodemographic form included questions, developed by Machado et al. (2003) and by the research team to collect sociodemographic data that characterize the child (age, sex, nationality and history of emotional and behavioral problems), the mothers (age, nationality, education, occupation, history of emotional and behavioral problems, marital status, and perceived quality of the marital relationship, classified using a 10-point scale ranging from 0-Not Positive At All to 10-Extremely Positive) and the household (residence area, socioeconomic status, number of persons included in the household and degree of kinship that the caregiver has with them, number of children and their age and (in)existence of other children in charge of the caregiver).

Inventário de Práticas Educativas (IPE; Machado et al., 2015). This self-report Questionnaire aims to identify the caregiver’s child-rearing practices used in the last year. This inventory consists of 29 items, organized in six dimensions: appropriate educational practices (e.g., praising the child when he behaves well); inappropriate but not abusive practices (e.g., threatening the child that you will hit him, not doing so); physical punishment (e.g., spanking in the hand, arm or leg); emotional abuse (e.g., locking the child in a dark room); potentially harmful behaviors (e.g., slapping the face, head or ears); and physical abuse (e.g., hitting causing injuries). For each item, parents are asked to report how frequently they used each of the presented child-rearing practices, using a 4-point Likert scale (I Never Used, I Used Once, I Use Less than Once a Month, I Used More than Once a Month). Parents are also asked to classify each of the presented child-rearing practices as adequate or inadequate. This self-report questionnaire is analysed item by item. For each item, the prevalence of each child-rearing practice (i.e., recategorizing the response options as Never Used vs. Used) in the dimension to which the item belongs and its classification as (in)adequate are calculated. For the purposes of the present study, we only considered the prevalence of the physical punishment items.

Escala de Crenças sobre Punição Física (ECPF; Machado et al., 2015). This self-report questionnaire assesses the degree of tolerance/acceptance of the use of physical punishment as an educational and disciplinary strategy. This scale consists of 21 items, answered on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), organized in four factors. The first factor (Legitimization of Physical Punishment for its Normality and Necessity) refers to the belief that physical punishment is an educational practice that is necessary and that there are negative consequences for children when parents didn’t use it. The second factor (Legitimization of Physical Punishment due to its Centrality and Necessity) assesses the degree to which the caregiver perceives physical punishment as a central strategy for child-rearing. The third factor (Legitimization of Physical Punishment by the Punitive role and Authority of the Father) reflects a traditional view of the parental role, in which the father is viewed as an authority figure in the family. Finally, the fourth factor (Legitimization of Physical Punishment by Parental Authority) refers to a conception of family life, framed on the values of caregivers’ authority and children’s duty of obedience and good behavior. A global score is calculated, by averaging items’ ratings. Global scores range from 21 to 105. Higher global scores indicate a greater degree of tolerance/acceptance toward the use of physical punishment for child-rearing (Machado et al., 2015). Cronbach’s alpha of the global score in the present sample was .89.

Data analysis

Data analyses were carried out, using IBM SPSS Statistics 28. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) were used to describe the maternal reported use of each physical punishment practice (coded as 1 - Used and 0 - Not Used) during the last year. Cochran’s Q tests followed by McNemar tests were conducted to examine the presence of significant differences in the use of the reported physical punishment practices.

Preliminary t-tests (for continuous variables) and chi-square tests (for categorical variables) to identify child, maternal and household characteristics associated with the most cited physical punishment practices during the last year. Binary logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the predictive role of child (block 1), maternal (block 2) and household (block 3) characteristics for the most cited physical punishment practices (dummy coded as: 0-Not Used, and 1-Used) during the last year. Statistical significance level was set at p<.05.

Results

Maternal reports of physical punishment practices during the last year

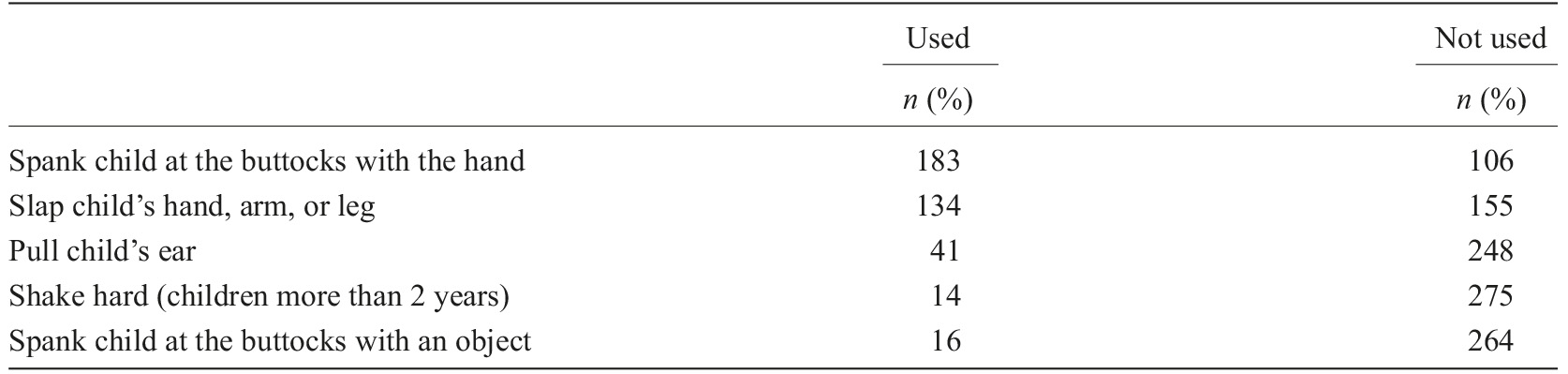

Table 1 displays the prevalence of use of each physical punishment practice during the last year. According to maternal reports, the most used physical punishment practices during the last year were spanking child at the buttocks with the hand and slapping child’s hand, arm, or leg. Cochran’s test showed that there were significant differences in the reported use of physical punishment practices, Q(4)=440.51, p<.001. McNemar a posteriori tests showed that the reported use of spanking child at the buttocks with the hand was significantly higher when compared with the reported use of pulling child’s ears (χ 2 =134.33, p<.001), slapping child’s hand, arm, or leg (χ 2 =31.56, p<.001), shaking hard (χ 2 =134.33, p<.001), and spanking child at the buttocks with an object (χ 2 =134.33, p<.001). Slapping child’s hand, arm, or leg was more used than pulling child’s ears (χ 2 =73.60, p<.001), shaking hard (χ 2 =112.39, p<.001), and spanking child at the buttocks with an object (χ 2 =105.95, p<.001). The use of pulling child’s ears was significantly higher when compared with the use of shaking hard (χ 2 =14.38, p<.001) and spanking child at the buttocks with an object (χ 2 =10.38, p=.001).

Predictive role of child, maternal and household characteristics for the most used physical punishment practices

Preliminary analyses showed that mothers who reported having spanked child at the buttocks were younger [t(247)=-2.54, p=.012], perceived a lower quality in their relationship with their partner [t(238)=-4.15, p<.001], considered physical punishment as globally more acceptable [t(238)=5.48, p<.001], had more [t(277)=3.27, p<.001] and younger children [t(277)=-3.66, p<.001] and tended to live with more persons [t(277)=1.96, p=.051] when compared with mothers who did not use this practice during the last year. With respect to slapping child’s hand, arm, or leg, preliminary analyses showed that mothers who reported having used this practice reported a higher acceptability toward physical punishment [t(278)=6.83, p<.001] and tended to have more children [t(278)=1.95, p=.052] when compared with mothers who did not.

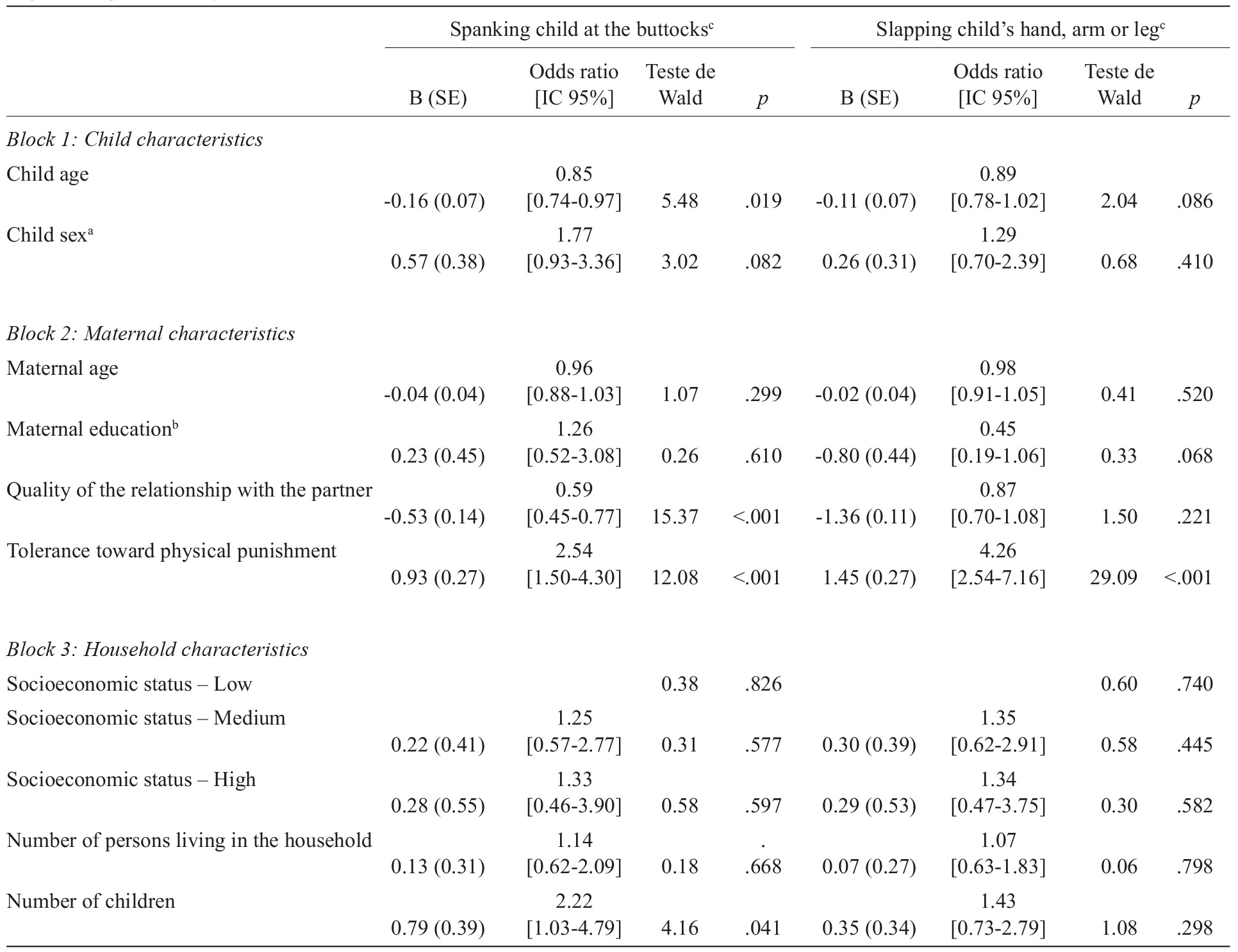

Table 2 displays the final binary logistic regression models for spanking child at the buttocks and slapping child’s hand, arm, or leg. With respect to spanking child at the buttocks, the first block (child characteristics) was significant, χ 2 =11.96, p=.03, -2 Log likelihood=281.37, pseudo-R 2 =.05 (Cox & Snell), .07 (Nagelkerke), Hosmer-Lemeshow: χ 2 =6.96, p=.549. According to mother’s reports, younger children (OR=0.85 [95% CI: 0.77-0.95]) were more likely to have been spanked at the buttocks in the last year. The inclusion of maternal characteristics (block 2) significantly improved the regression model, χ 2 =39.30, p<.001, -2 Log likelihood=242.97, pseudo-R 2 =.21 (Cox & Snell), .28 (Nagelkerke), Hosmer-Lemeshow: χ 2 =7.22, p=.513. Mothers who had younger children (OR=0.88 [95% CI: 0.77-0.99]), perceived the quality of their marital relationship as less positive (OR=0.61 [95% CI: 0.48-0.79]) and physical punishment as more acceptable (OR=2.73 [95% CI: 1.64-4.53]) were more likely to report having spanked child at the buttocks during the last year. The third block (household characteristics) was statistically significant (χ 2 =14.24, p=.007). As shown in Table 2, the final binary logistic regression model showed that mothers who reported having more and younger children, a lower quality in their relationships with partners and a higher global tolerance toward physical punishment were more likely to have spanked child at the buttocks with the hand during the last year.

Table 2 Final binary logistic regression models to examine the predictive role of child, maternal and household characteristics for the mother’s reported use of spanking child at the buttocks and slapping child’s hand, arm or leg during the last year

Note. Overall model statistics for spanking child at the buttocks: χ 2 =65.52, p<.001, -2 Log likelihood=227.83, pseudo-R 2 =.25 (Cox & Snell), .35 (Nagelkerke), Hosmer-Lemeshow: χ 2 =4.19, p=.839, Percentage of correctly classified cases: 73%. Overall model statistics for slapping child’s hand, arm, or leg: χ 2 =57.54, p<.001, -2 Log likelihood=249.59, pseudo-R 2 =.23 (Cox & Snell), .30 (Nagelkerke), Hosmer-Lemeshow: χ 2 =7.61, p=.472, Percentage of correctly classified cases: 71%. aDummy-coded as 1-Boy, 0-Girl; bDummy-coded as 1-College education, 0-1-12 years; cDummy-coded as 1-Used, 0-Not Used.

With respect to slapping child’s hand, arm, or leg, the first block (child characteristics) was not statistically significant, χ 2 =5.49, p=.064, -2 Log likelihood=301.67, pseudo-R 2 =.02 (Cox & Snell), .03 (Nagelkerke), Hosmer-Lemeshow: χ 2 =21.63 p=.006. The inclusion of maternal characteristics (block 2) significantly improved the regression model, χ 2 =47.92, p<.001, -2 Log likelihood=253.75, pseudo-R 2 =.21 (Cox & Snell), .29 (Nagelkerke), Hosmer-Lemeshow: χ 2 =5.34, p=.720. Mothers who didn’t hold a college degree (OR=0.42 [95% CI: 0.19-0.93], p=.032) and who perceived physical punishment as more acceptable (OR=4.47 [95% CI: 2.67-7.47], p<.001) were more likely to have slapped child’s hand, arm, or leg during the last year. The third block (household characteristics) was not statistically significant, χ 2 =4.16, p=.385. As shown in Table 2, the final binary logistic regression model showed that only mothers who reported a higher global tolerance toward physical punishment were more likely to have slapped child’s hand, arm, or leg.

Discussion

This study aimed to describe the maternal reports about the use of different physical punishment practices in the last year and to analyse the predictive role of children’s, household’s, and mother’s characteristics in the use of different physical punishment practices during the last year.

Our findings showed that spanking child at the buttocks with the hand and slapping child’s hand, arm, or leg were the most reported by mothers in our samples, during the last year. Nearly half of the mothers in our sample reported having used these physical punishment practices at least once during the last year. This prevalence was higher in the Portuguese study of Machado et al. (2003), which involved a sample of fathers and mothers aged 20 to 67, who hold more diverse educational qualifications and had more children of younger ages than the participants from our sample. Furthermore, data collection for the study of Machado et al. (2003) took place in the North Portugal, before the legislation shift, prohibiting all forms of violence against children and adolescents. According to the bioecological system framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), the time and context in which the child grows up influence the way the child interacts with caregivers and vice versa. The macrosystem (which includes the cultural and regional context) shapes values, beliefs, and practices in relation to child development, exerting an indirect influence on the child’s development through the way caregivers interact with them. These values, beliefs, and practices regarding child development change over time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Previous research has also shown that local norms shape the acceptability of physical punishment and its use (Cappa & Khan, 2011; Chiocca, 2017; Durrant et al., 2003; Pinderhughes et al., 2000; Straus, 1994).

In our sample, pulling child’s ears, shaking hard (child aged more than two years) and spanking child at the buttocks with an object were the least reported physical punishment practices during the last year. This may be because most of these practices are closer to the theoretical definition of physical abuse, which can be defined as the acts that exceed the severity legally permitted and increase the risk and probability of causing harm to the child (Clément & Chamberland, 2014). Unlike physical abuse, physical punishment is characterized by inflicting pain, but without causing physical damage (Clément & Chamberland, 2014). Furthermore, the prevalence of these physical punishment practices in our sample was lower than in the study of Machado et al. (2003) conducted before the legislation shift, suggesting a generalized decrease in the reported use of physical punishment over time.

With respect to the second objective, our findings showed that maternal tolerance toward physical punishment was the most consistent and strongest predictor of the use of spanking child at the buttocks with the hand and slapping child’s hand, arm, or leg during the last year. These results can be understood based on the Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance (1968), in which mothers are expected to develop behaviors congruent with their beliefs. These results are also consistent with the idea that the parents’ cognitions about caregiving and parenting (Sigel et al., 1992) are expressed by parental practices (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Furthermore, our results are in line with prior research, showing that beliefs about the effectiveness of hitting (Patias et al., 2012) and positive attitudes toward physical punishment (Jackson et al., 1999) were associated with a greater use of this parenting practice (Bunting et al., 2010; Cappa & Khan, 2011; Durrant et al., 2003; Holden et al., 1995; Holden et al., 1999; Vittrup et al., 2006).

Nevertheless, our results also showed that mothers who classified their relationship with their partners as less positive and, to a lesser extent, those who had more and younger children, were less likely to have spanked child at the buttocks with the hand during the last year. These findings are consistent with the process-contextual model proposed by Gershoff (2002) and with empirical studies conducted in other cultural contexts (Abdel-Fatah, 2021; Cappa & Khan 2011; Durrant et al., 2003; Gershoff, 2002; Grogan-Kaylor et al., 2018; Ward et al., 2021; Vittrup et al., 2006). Parents who experience more stress, such as those who are involved in more negative marital relationships or have more children, are more likely to use more aggressive disciplinary strategies, because they may experience more intense cognitive-emotional processes and reactive processes (Pinderhughes et al., 2000) than parents who experience lower levels of stress. This may increase parents’ hostile attributions toward children’s misbehaviors (Dix, 1991). Based on a developmental perspective, the process-contextual model acknowledges that older children are less likely to be exposed to physical punishment practices, as mothers tend to adapt their disciplinary strategies as the child grows up (Gershoff, 2002). As they grow up, children also internalize rules and limits and gradually display less transgressive behaviors than at younger ages, so that mothers may be less likely to use physical punishment (Jaffee et al., 2004).

The predictive role of the remaining child, parental and household factors for the use of the most reported physical punishment practices was limited in our sample. Previous studies showed that less educated mothers of younger boys, from lower socioeconomic statuses were more likely to use physical punishment (Abdel-Fatah, 2021; Grogan-Kaylor et al., 2018). In contrast, maternal education, household income and children’s sex did not emerge as significant predictors for the use of physical punishment in our sample. These findings may reflect methodological differences when compared with prior research. In our sample, mothers completed a self-report questionnaire on the use of physical punishment practices in the last year and their responses were analysed, using a categorical approach (i.e., use vs. non-use of physical punishment practices) and an item- by-item level of analysis. In prior research, parents were interviewed and the frequency of use of more severe punitive practices were analysed, using a dimensional approach (Abdel-Fatah, 2021; Cuartas et al., 2019; Gershoff, 2002; Grogan-Kaylor et al., 2018; Taillieu et al., 2014; Ward et al., 2021).

Despite its contribution for the state-of-art knowledge, this study has limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, participants were recruited, using a convenience sampling method. Thus, our findings mostly reflect the perspectives of highly educated and married/cohabitating mothers from medium socioeconomic backgrounds toward physical punishment. Furthermore, participants were recruited online, mostly through advertisements in social media groups about parenting, who may be particularly motivated or interested in the topic under investigation. Second, in accordance with the recommendations of the authors of the instrument, physical punishment practices were assessed, using a categorical and item by item analysis (Machado et al., 2015). The categorical analysis of responses may have limited the distinction between mothers who used the practice occasionally (at least once in the last year) and mothers who used it regularly. However, the Inventário de Práticas Educativas (Machado et al., 2015) is the only validated instrument for the assessment of physical punishment practices in Portugal. Furthermore, the analysis of the frequency of use of physical punishment practices (as a continuous variable) could be more likely to reflect social desirability. In fact, mothers may be less likely to report the regular use of physical punishment practices, due to legal restrictions. Third, data collection took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. The heightened levels of family stress associated with this global stressor (Wu & Xu, 2020) may have influenced maternal reports of physical punishment (Gershoff, 2002).

Future studies need to overcome these limitations in sample composition, use a multi-method (e.g., interviews, archival data), multi-informant (e.g., comparing reports of physical punishment of both members of parental dyad and children), and multi-context approach and provide a more comprehensive analysis of the frequency and severity of physical punishment practices, based on a common definition and operationalization. Conducting cross-cultural studies can also be important because the use and beliefs about physical punishment practices are likely to be influenced by the culture (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Cappa & Khan, 2011; Durrant et al., 2003; Pinderhughes et al., 2000; Straus, 1994).