For over a decade, attachment researchers have been examining the hypothesis offered by Waters and Waters (2006) that a central element of internal working models (Bowlby, 1973, 1982) is a script about being and using a secure base. A substantial body of research has demonstrated the reliability and validity of secure base script use when narrating attachment-relevant events as a general index of attachment security for adults (e.g., Schoenmaker et al., 2015; Vaughn et al., 2006; Waters et al., 2013, 2017), adolescents (e.g., Dykas et al., 2006; Steele et al., 2014; Vaughn et al., 2016), middle-childhood (e.g., Psouni & Apetroaia, 2014; Waters et al., 2015), and more recently, early childhood (e.g., Posada & Waters, 2018; Vaughn, Posada, & Veríssimo, 2019; Vaughn, Posada, Veríssimo et al., 2019). It is interesting and somewhat ironic to note that while the bulk of studies concerning secure base script use in early childhood appeared considerably later than did studies of script use by adults, the phrase “secure base script” was coined by Waters et al. (1998) in their re-analysis of Attachment Story Completion Test (ASCT) data originally reported by Bretherton et al. (1990).

In part, the later entrance of early childhood can be attributed to the fact that for adults, adolescents, and school-age children, the method of choice for assessing secure base script (SBS) use has been word-prompt lists that present a story “outline” if the columns of words are read from left to right on the page. This method is inappropriate for children under about eight or nine years of age, namely for preschoolers since they have relatively limited vocabularies and (for the most part) cannot read effectively. However, the ASCT elicits narratives that elaborate on attachment relevant themes that are prompted initially by the researcher. For example, the researcher starts by setting the scene of the event by presenting the characters and the general topic (e.g., birthday party), then introduces a challenge (e.g., the child accidentally spills juice), then asks the child, “show me and tell me what happens next.” This story stems elicit stories with a range of thematic content, but for most children, it is possible for a rater to detect the elements of the SBS. Waters et al. (1998) described a method for sorting transcripts of the stories according to the quality and completeness of the SBS using a three-point scale, which was modified by Vaughn, Posada, Veríssimo et al. (2019) in order to assign SBS scores on a seven-point scale similar to the scale used for older children and adults. The validity of this modified scoring for SBS is suggested by its positive and significant associations with other well-validated attachment measures (e.g., the Strange Situation, Attachment Q-sort, and ASCT scales for security and coherence, see Vaughn, Posada, Veríssimo et al., 2019).

The central focus of this study is to examine the stability of children’s attachment representations using the SBS [ASCT protocol; Bretherton et al., 1990, using the Vaughn, Posada, Veríssimo et al. (2019) score criteria] at age 5 years and using the self-reported Kerns Security Scale (KSS; Kerns et al., 1996) at ages 8 and 9 years in a Portuguese sample. Kerns et al. (1996) reported a preliminary analysis demonstrating the convergent and discriminant validity of their scale and Brumariu et al. (2018) published a meta-analysis of 57 studies suggesting that the KSS was a valid indicator of attachment during middle childhood.

There are several earlier studies suggesting that mental representations of attachment can show moderate stability across this range of ages (e.g., Ammaniti et al., 2000; Dubois-Comtois et al., 2011; König et al., 2007) but none of these studies assessed the child’s use of the SBS at either the initial assessment or the follow-up. Data from this study will allow us to determine whether the SBS score behaves like other attachment measures for early childhood in this regard. The König et al. (2007) study included separate attachment scores for mothers and fathers. Because the KSS has separate items for mothers and fathers, we were also able to examine the cross-time prediction of both parents’ scores. Based on the results of a large meta-analysis reported by Pinquart et al. (2013) we expected to find moderate and significant cross-time associations between the earlier assessment and assessments at both 8 and 9 years. We hypothesized that significant associations would be found for both parents (at both age levels).

Method

Participants

Participants were 70 preschool children (36 girls). Children’s age ranged from 51 to 69 months (M=60.54; SD=5.44), at the first data point collection. The range of mothers’ ages was 29-51 years (M=37.44; SD=4.39) and fathers’ ages ranged from 34-62 years (M=38.63; SD=4.82). The children attended private daycare preschools in the suburbs of Lisbon, Portugal. All participating children were European and both parents lived in the household. All families were “middle class” by the standards of the local community. Data for the Kerns Security Scale was collected when the children were 8 and again one year later.

Measures

Attachment Story Completion Task (ASCT; Bretherton et al., 1990). The ASCT was used to assess children’s attachment representations. A series of story-stems were presented to the child to elicit narratives regarding attachment behaviors toward caregivers. Story stems were presented using dolls and household props, including a mother, father, child, sibling, kitchen equipment, living room, and bedroom furniture, etc. The child doll was the same sex as the child being assessed. The assessments took place in a quiet area outside the classroom. The interviewer invited the child to play the story completion game together, the interviewer began each story and then asked the child to freely continue and finish the story, illustrating behaviors, emotions, and interactions between characters. Same non-directive questions were used to facilitate the child’s narrative production such as “Does anything else happen in the story?” or “What are they doing?” The child was first presented with a story stem about a birthday party with a pleasant but non-attachment related theme, this was intended as a warm-up story and was not scored. The child was then presented with five primary attachment-related stories-stems (for this study only 3 - monster, separation, and reunion stories - were used and coded for SBS content).

All stories were rated by two independent trained coders who were blind to any other information about the child. Coders assigned a single score on a 7-point scale for secure base scriptedness based on a modification of Waters and colleagues (1998) coding system, and a global score was given to the three stories (Vaughn, Posada, Veríssimo et al., 2019). As mentioned, these summary scores of the three stories could range from 1 (odd/deviant stories that include failure of the attachment figure to protect the child, and/or failure to recognize the attachment relevance of the events being represented in the narrative) to 7 (complete stories that clearly suggested a secure base for exploration and a haven of safety when needed). Inter-observer reliability was assessed using intraclass correlations and ranged between .79 to .83 across observer pairs.

Kerns Security Scale (KSS; Kerns et al., 1996). The KSS questionnaire measures the degree to which the child sees the mother/father as a responsive and available figure. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale using Harter’s (1982) format “Some kids... but… Other kids”, with higher scores indicating greater security. Specifically, for each question, the child is presented with two different types of children, and then must decide which is more similar to them, e.g., “Some kids wish their dad would help them more with their problems, BUT other kids think their dad helps them enough”. After that, the child specifies whether they are “sort of like” or “really like” the child in the question. Each item is scored from 1 to 4, with a higher score representing greater security. The 15 items were aggregated in a single dimension that measured attachment security to mother/father. The value for the security Cronbach’s alphas was .89 for mother and .91 for father. The KSS was translated from the original English version into Portuguese following the procedures outlined by “Committee Approach” (Brislin, 1980), a methodology for cultural adaptation of psychological questionnaires. A first version was then applied to a small group of children, to ensure that all items were understandable and thus suitable.

Procedures

Participating children were interviewed with the Attachment Story Completion Task (Bretherton et al., 1990) at their child-care facility during the winter academic term (between January and March). For the primary school data collection, data was collected after the permission of the school authorities and after receiving the informed consent of families. All classroom assessments were performed during regular school hours, in class, during a single 45 minutes’ session. A research assistant was present to introduce the study and to answer questions. The instructions given emphasized the confidentiality of the data, the voluntary participation, and the importance of completing the questionnaire individually. All participating children give their informed assent.

Results

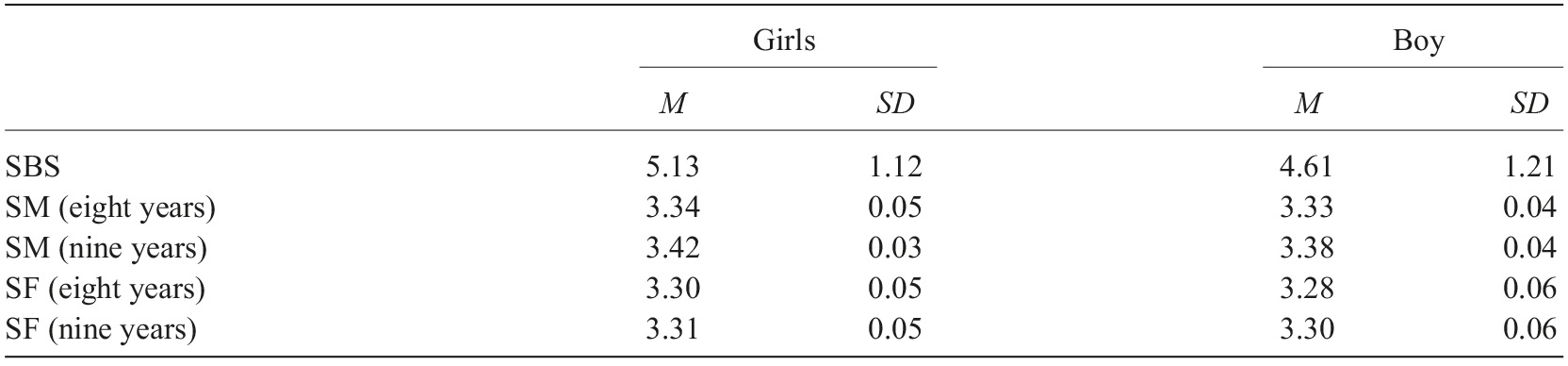

First, we present the descriptive results and associations between our variables. Like in previous studies (see Fernandes et al., 2019; van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2010) sex differences were found in this sample [F(1,69)=3.07, p<0.05] for Secure Base Script (SBS) favoring girls (see Table 1).

Table 1 Descriptive values comparing boys and girls

Note. SBS=Secure Base Script; SM=Secure Mother; SF=Security Father.

No sex differences were found for security to both mother and father at 8 [F(1,69)=0.04, p>.05, and F(1,69)=0.03, p>0.05 respectively] neither at 9 years old [F(1,69)=0.29, p>.05 and F(1,69)=0.04, p>.05, respectively].

The correlations between mother’s and father’s security scores were significant at both 8 (r=.73, p<.001) and 9 years (r=.65, p<.001). Correlations between mothers’ security scores at ages 8 and 9 were significant and this was also true for fathers (r=.44, p<.001 and r=.37, p<.01, respectively).

Secure base script and later attachment representations

Pearson correlations tested associations between attachment representations at age 5 and perceived attachment quality to each parent at ages 8 and 9, controlling for sex. Significant and positive associations between secure attachment representations at age 5 and perceived attachment security to mother and to father at age 8 and 9 were obtained. Specifically, significant associations were found between secure attachment representations at age 5 and perceived attachment security to mother at age 8 (r=.28, p<.05) and age 9 (r=.25, p<.05). Corresponding correlations with fathers were also significant at ages 8 and 9 (r=.42, p<.01; r=.38, p<.01, respectively). Finally, because security to mother and security to father were highly associated, we created a composite using both measures. A significant association was found between secure base script and secure representations at age 8 (r=.43, p<.01) and age 9 (r=.42, p<.01). The magnitudes of correlations for mothers vs. fathers vs. secure composite were not significant (tests on r to Z transformed scores).

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to assess the longitudinal stability of attachment representations from early to middle childhood, using a recently described method (Vaughn, Posada, Veríssimo et al., 2019) to evaluate narratives with the ASCT protocol. Consistent with results of previous studies and meta-analyses (e.g., Dubois-Comtois et al., 2011; Pinquart et al., 2013), we found that children with higher secure base script scores (SBS) at age 5 reported feeling more secure with both parents at ages 8 and 9. Cross-age security scores for mothers and fathers were high.

The substantial relation between father and mother security scores suggests that by middle childhood children are beginning to merge their most significant attachment relations into a single model, integrating models across attachment figures, rather than separate models for each major attachment figure (see also van IJzendoorn et al., 1992). However, it is possible that some children have discrepant models for mothers and fathers. It will be important for future research to examine children from families who have experienced major disruptions between early and middle childhood (e.g., by divorce or death of a parent), to determine whether these children show such discrepant characterizations of security with both parents.

Our findings are potentially important for attachment researchers because the use of the script score is now well established for early childhood samples (see Posada & Waters, 2018; Vaughn, Posada, & Veríssimo, 2019), as well as for adult, adolescent, and middle childhood samples. This means that researchers interested in documenting the growth of attachment representations over time now have a method for obtaining narrative data that can be scored for SBS content according to a common set of rules from early childhood to maturity. Of course, there is some difference in the protocols used to elicit these narratives, but the data now available indicates that access to and use of the SBS has the same meaning across a very broad range of ages.

We also identify limitations to the present study. Our sample is small, and participants are all from stable, middle to upper-middle class families attending private institutions. Replications of this study with larger samples and other cultures are necessary to explore the hypothesis that attachment representations are stable from early to middle childhood and start to show convergence across parents. We also recognize that this study would have been stronger if we had been able to use the middle-childhood word lists to obtain SBS information from our participants and eight and/or nine years of age. However, when these data were collected, the middle-childhood word lists and scoring rules had not been validated (Waters et al., 2015). This will be a task for the future. Future research should also expand the study of developmental trajectories and collect more information about the daily lives of participating families (e.g., conflict in the family, other parenting stressors, loss of an attachment figure in either nuclear or extended families, etc.), contrasting children with similar relations with both parents to those whose representations of parents are discrepant.

Overall, our results indicate that access to and use of SBS in young children’s attachment-relevant narratives is a valid and potentially productive measure. Narrative scriptedness not only shows expectable associations with concurrent measures of attachment and social adaptation (Fernandes et al., 2019; Posada & Waters, 2018; Posada et al., 2019; Vaughn, Posada, & Veríssimo, 2019), but also significantly predicts perceived attachment quality to both parents in middle childhood.