Introduction

Shame is a self-conscious emotion that can be understood as the product of a complex set of cognitive activities (Lewis, 2022) that translate complex ideas about the self, typically characterized by a feeling of inferiority and worthlessness, leading to a desire to escape or disappear (Tracy & Robins, 2004). According to Gilbert (2003), shame can be experienced internally and externally. External shame refers to the way one believes oneself to exist in the minds of others as unworthy, undesirable, inferior, defective, and unattractive (Allan et al., 1994; Gilbert, 1998, 2003; Kaufman, 1989; Lewis, 1992; Tangney & Dearing, 2002; Tangney & Fischer, 1995). In turn, internal shame is internally focused, involving negative self-evaluations of the self as inadequate, inferior, undesirable, empty or isolated (Gilbert, 2003).

From a developmental perspective, changes in social relationships, the physical changes associated with puberty, psychosocial tasks such as identity formation, increased ambition, and performance concerns that characterize adolescence increase the situational contexts in which self-evaluation is likely to occur (Gilbert & Irons, 2009; Reimer, 1996). Thus, shame may become increasingly prominent at this developmental stage (Reimer, 1996), especially in girls due to differences in socialization and social expectations (Else-Quest et al., 2012).

Research has shown that high levels of shame in adolescence are associated with a variety of psychological symptoms, including anger and aggression, internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety and depression), eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorders and personality disorders, as well as risk behaviors, such as suicidal behaviors or substance abuse (e.g., Cunha et al., 2012; Muris et al., 2016; Muris & Meester, 2014; Paulo et al., 2019; Xavier et al., 2016). Therefore, it is important to identify the factors associated with high levels of shame in adolescence to design evidence-based interventions that can promote more adaptive developmental trajectories.

Some authors have argued that high levels of shame develop in the context of social interactions (Gilbert, 2003), particularly relationships with parents. According to attachment theory (Bowlby, 1982), attachment relationships with parents are associated with the quality of subsequent social relationships, particularly with peers (Pallini et al., 2014) and with children’s ability to regulate their emotions using more adaptive strategies (Cooke et al., 2019). Specifically, children who establish repeated and consistent interactions with sensitive and responsive caregivers in infancy, begin to develop expectations that they can rely on their parents’ support to explore the world (secure base) and to support them (safe haven) in emotionally demanding situations. These expectations are internalized as mental representations (dynamic internal models) during childhood and are consolidated during adolescence (Dykas & Cassidy, 2011). In early adolescence, young people begin to acquire greater autonomy and spend less time with their parents. Thus, there is a shift in the objectives of the attachment system from seeking closeness to the availability of parental support for the personal development of adolescents and in situations where they feel emotionally overwhelmed (Allen, 2008; Kerns & Brumariu, 2016). Attachment becomes more reciprocal as parents and young adolescents establish a cooperative partnership in which both partners take responsibility for communicating and coordinating access and contact with attachment figures (Kerns et al., 2011; Waters et al., 1991). However, representations of parents as a safe haven and secure base continue to play an important role (Kerns & Brumariu, 2016), influencing how young adolescents regulate their emotions, including self-conscious emotions, such as shame.

Empirical evidence of an association between attachment to parents and the regulation of self-conscious emotions in early adolescence, particularly shame, is still scarce (Costa-Martins et al., 2021, for a review). Most of the research to date has been conducted with young adults, primarily university students, and has been characterized by great variability in how attachment and shame are conceptualized (e.g., Akbag & Imamoglu, 2010; Beduna & Perrone-McGovern, 2019; Gross & Hansen, 2000; Martins et al., 2016; Passassini et al., 2015; Sedighimornani et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2005). The studies conducted to date showed relatively consensual results, showing that young adults who report insecure attachment patterns (e.g., Akbag & Imamoglu, 2010; Passassini et al., 2015; Sedighimornani et al., 2021) or attachment patterns characterized by higher levels of anxiety and avoidance (e.g., Martins et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2005) describe higher levels of global shame. In contrast, these studies have shown that young adults who report secure attachment patterns (Beduna & Perrone-McGovern, 2019; Passanisi et al., 2015) describe lower levels of global shame.

The few empirical studies conducted with adolescents have corroborated the positive associations between perceptions of insecure attachment and greater alienation in the relationship with parents and reports of maladaptive shame (Houtackers, 2015; Muris et al., 2014). Despite their contribution, existing empirical studies in adolescence have essentially examined the levels of global shame and have not considered that shame can be experienced externally and internally (Gilbert, 2003). On the other hand, these empirical studies have not examined these associations by considering the attachment relationships that young adolescents establish with mothers and fathers separately. However, the attachment theory describes that children’s and adolescents’ attachment relationships with mothers and fathers can be different and complementary, and therefore, specific to each parental figure (Ainsworth, 1989; Bretherton, 2010; Thompson, 2016). Mothers are often seen as safe haven providers, while fathers are seen as facilitators of the child exploration (Grossman & Grossman, 2020). Research has shown that fathers are seen by adolescents as more encouraging of independence, while mothers are more accepting (McCormick & Kennedy, 1994).

To overcome current gaps in the literature, the main aim of this study was to examine the associations between adolescents’ reports of safe haven and secure base in their relationships with mothers and fathers and self-reported levels of total, internal, and external shame. We hypothesized that adolescents who describe higher levels of safe haven and secure base in their relationships with parents will report lower levels of total, internal, and external shame. Due to the few available evidence in the literature, we didn’t establish hypotheses for differential associations between attachment security and shame, when considering the relationship with mothers and fathers.

Method

Participants

A total of 312 adolescents took part in the study. The inclusion criteria for the study were children or adolescents: (1) being aged 10 to 15 years old; (2) being able to read and understand Portuguese; (3) having been authorized by their parents to take part in the study; and (4) having agreed to take part in the study. The participants were, on average, 12 years old (SD=1.52). Concerning gender, 45% were boys. A total of 30% were in 5th grade, 32 in 6th grade, 10% in 7th grade, 9% in 8th grade and 18% in 9th grade. For place of birth, 78% had Portugal as their country of origin.

With respect to the parents, the participants stated that the mothers were on average 44 years old (SD=5.47) and that the fathers were on average 45 years old (SD=6.11). According to the participants, 50% of the parents were married, 33% were separated or divorced, 15% were unmarried, 2% reported another marital status. The participants reported that 53% of the mothers and 45% of the fathers held a university degree. With respect parents’ job status, the participants reported that 58% of the mothers worked full-time, 32% worked part-time and 10% were not working. The participants also reported that 75% of the fathers worked full-time, 22% worked part-time and 2% were not working. A total of 83% of participants reported having siblings.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Portuguese General Directorate for Education and by the school board of a public school in the Lisbon Metropolitan area, Portugal. Following this approval, written informed consent was obtained from legal guardians, explaining the objectives and procedures of the study, the voluntary nature of adolescents’ participation, and the confidentiality of the data. A total of 332 (54%) adolescents were authorized to participate by their parents.

Data collection was carried out in groups, by two trained researchers, on schedules that were agreed with the head teachers. These researchers explained the instructions for completing the questionnaires to adolescents and were available to answer any questions. Of the 332 adolescents authorized to take part in the study by their parents, 6 were absent on the day the questionnaires were administered, 8 refused to take part and 6 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or did not complete all the questionnaires. Participants completed the questionnaires on paper (26%) or online (74%), depending on their preference.

Instruments

Socio-demographic form: This form was used to collect data on the socio-demographic characteristics of the adolescents (e.g., sex, age, grade, country of birth, siblings) and the parents (e.g., marital status, education).

Security Scale Questionnaire (SSQ; Kerns et al., 2015; Portuguese version: Fernandes et al., 2021): This 21-item self-response scale aims to assess the degree to which the child sees their mother and father as responsive and available figures during middle childhood and early adolescence (Kerns et al., 2015). It consists of two subscales: (1) Safe Haven (14 items), which assesses open communication about needs and emotions and whether a child uses their parents as a safe haven when they are suffering; and (2) Secure Base (7 items), which assesses parental encouragement and support for exploring novelty. For each parental figure, the adolescent is presented with items that describe two different types of adolescents and then the adolescent is asked to decide which is more similar to them. The adolescent responds to each of the items using a 4-point scale based on Harter’s (1982) format, indicating how similar they feel to the type of adolescent chosen (Exactly like Me, More or Less like Me). Scores are calculated for the Secure Base and Safe Haven dimensions for the mother and father separately, based on the average scores of the items that make them up. Higher scores represent greater security in the attachment to the mother and father. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alphas for the mother were .82 for the Safe Haven dimension and .76 for the Secure Base dimension. For the father, Cronbach’s alphas were .87 for the Safe Haven dimension and .74 for the Secure Base dimension.

External and Internal Shame Scale for Adolescents (EVEI-A, Cunha et al., 2021; Silva & Cunha, 2019): This scale is a version of the Internal and External Shame Scale originally developed for adults (Ferreira et al., 2019, 2022), adapted for adolescents between the ages of 12 and 19 years. The EVEI-A has kept the 8 items from the adult version of the scale but has been modified so that its language is more familiar to adolescents. Each item is answered on a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 - Never to 4 - Always). The scale is divided into two sub-dimensions of shame: (1) external shame (e.g., “Others judge and criticize me”); and (2) internal shame (e.g., “I am different and inferior to others”). Scores are calculated for each of the Internal Shame and External Shame subscales, as well as an overall Shame score, based on the average of the scores for the respective items. Higher scores indicate a greater perception of shame. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alphas were .89 for total shame, .80 for internal shame, and .78 for external shame.

Data analysis

Data analyses were performed, using IBM SPSS version 29. Preliminary correlation analyses were performed to examine the associations between the study variables (perceived safe haven and secure base in the relationship with the mother and the father, total shame, external and internal shame) and to identify potential sociodemographic covariates with the outcome variables.

Due to the interdependence between the attachment security scores for mothers and fathers, a linear mixed regression model was performed, so that attachment security scores for both parents were nested within adolescents. Given the magnitude of the correlations between safe haven and secure base scores for mothers and fathers (r=.72 and r=.74, respectively), linear mixed regression analyses were performed for each dimension separately. Each attachment dimension (safe haven or secure base), caregiver status (dummy coded: 1 - mother, 0 - father), and the interaction term (Safe Haven x Caregiver Status, or Secure Base x Caregiver Status) were introduced in the regression model for each of the outcomes (total shame, internal shame, and external shame).

Statistical significance was set at p<.05, but marginally significant interactions (p<0.10) were also reported. When marginally significant or significant interactions were identified, simple slopes analyses were conducted, using Modgraph (Jose, 2013).

Post hoc a posteriori power analyses, using G-Power (Faul et al., 2007, 2009), showed that medium effects (f≥.03) could be detected.

Results

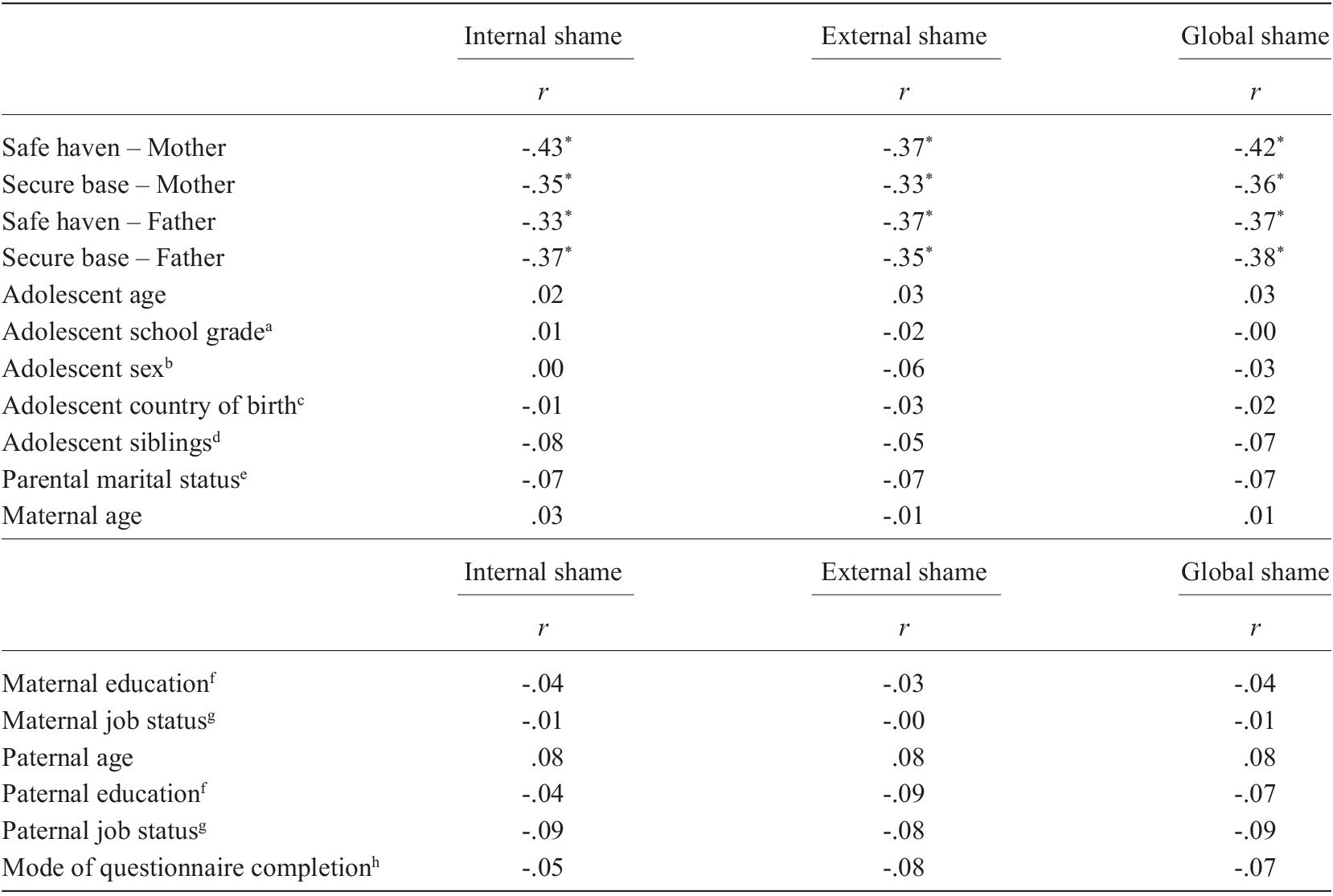

Table 1 presents the correlations of the sociodemographic variables and attachment scores for both parents with the outcome variables (total, internal, and external shame). Negative correlations of moderate magnitude were found between perceived secure base and safe haven in the relationship with both parents and the outcomes variables (total, internal, and external shame). However, preliminary correlation analyses didn’t identify sociodemographic correlates with the outcome variables (total, internal, and external shame).

Table 1 Correlations between sociodemographic characteristics, perceived safe haven and secure base in the relationship with the mother and the father and outcome variables (internal, external and global shame)

Note. aDummy-coded as: 1 - 5th/6th grade, 0 - 7th to 9th grade. bDummy-coded as: 1 - Girl, 0 - Boy. cDummy-coded as: 1 - Portugal, 0 - Other. dDummy-coded as: 1 - Yes, 0 - No. eDummy-coded as: 1 - Married/cohabitating, 0 - Other. fDummy-coded as: 1 - University degree, 0 - Other. gDummy-coded as: 1 - Employed, 0 - Unemployed. hDummy-coded as: 1 - Paper, 0 - Online. * p<.05.

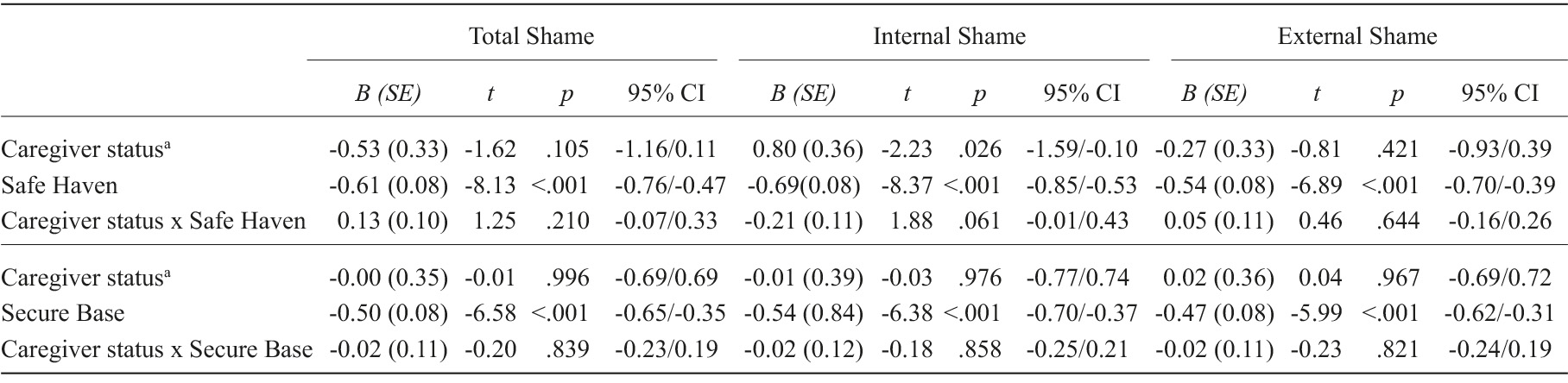

Table 2 summarizes the findings of the linear mixed regression analyses examining the associations of perceived safe haven and secure base in the relationship with both parents in self-reported total, internal and external shame.

Table 2 Predictive role of attachment dimensions (safe haven or secure base), caregiver status, caregiver status x attachment dimensions (safe haven or secure base) on total shame, internal shame and external shame

Note. aDummy-coded as: 1 - Mother, 0 - Father.

Independent of the caregiver status (mother vs. father), Table 2 shows that adolescents who displayed higher scores of safe haven and secure base reported lower levels of total shame.

Concerning shame subscales, Table 2 shows that participants who displayed higher scores of secure base reported lower levels of internal shame. However, a marginally significant Caregiver Status x Safe Haven was observed. Simple slopes analyses showed that adolescents who displayed higher scores of safe haven in their relationships with the mother (t=-11.62, p<.001) and the father (t=-8.25, p<.001) reported lower levels of internal shame. The magnitude of the associations between safe haven and internal shame was stronger in the relationship with the mother than in the relationship with the father.

Independent of the caregiver status (mother vs. father), participants who displayed higher scores of secure base and safe haven reported lower scores of external shame (see Table 2).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the associations between adolescents’ reports of safe haven and secure base in their relationships with mothers and fathers and self-reported levels of total, internal and external shame. Overall, our findings showed that adolescents with higher scores of safe haven and secure base in their relationships with both mothers and fathers reported lower levels of total, internal and external shame. The magnitude of the negative associations between adolescents’ reports of safe haven and internal shame was greater when the relationship with the mother was considered.

Our results corroborate our research hypothesis and are consistent with the majority of studies conducted with university students, showing that secure attachment patterns are associated with lower levels of global shame (Akbag & Imamoglu, 2010; Beduna & Perrone-McGovern, 2019; Passassini et al., 2015) and submissive patterns (self-attack and withdrawal) of shame management (Sedighimornani et al., 2021). The obtained findings are also in line with the few studies conducted on samples of children and adolescents (Costa-Martins et al., 2021), indicating that children and adolescents who rated their attachment as insecure and described lower levels of security and higher levels of alienation in their relationship with parents reported higher levels of perceived shame (Houtackers, 2015; Muris et al., 2014).

In contrast to studies conducted to date in samples of children and adolescents (e.g., Houtackers, 2015; Muris et al., 2014), our findings provide further evidence on the relationships between attachment to parents and shame, by examining the perceptions of safe haven and secure base in the relationship with the father and mother and measuring both internal and external shame. These findings can be understood based on the theoretical contributions of attachment theory in middle childhood and adolescence (Kerns & Brumariu, 2016). Adolescents who experience higher levels of trust in the availability of both parents to communicate openly about their emotions and to assist them in distressing situations and who perceive higher levels of encouragement from both parents to explore novelty and increased respect for their own perspectives (Kerns et al., 2015; Kerns & Brumariu, 2016) may hold more positive expectations about the self and others, based on the belief that the self is valued by others (Martins et al., 2016). Our findings are also in line with the idea of Reimer (1996), establishing that shame typically results from difficulties in acquiring autonomy and meeting the expectations of significant others, so that the self is seen as unworthy of love and admiration. On the other hand, several meta-analyses have concluded that secure attachment to parents is associated with better social and emotional competence in childhood and adolescence (Cooke et al., 2019; Groh et al., 2014). These competencies can prepare adolescents to cope adaptively with the challenges in social relationships and social context, the physical changes associated with puberty and the psychosocial tasks (such as identity development) that characterize adolescence and increase the contexts in which self-evaluation occurs (Reimer, 1996). Consequently, adolescents who perceive their parents as more available in distressing situations and more encouraging of exploration (Kerns & Brumariu, 2016) may be less likely to evaluate themselves as inferior, inadequate, undesirable, empty, or isolated and may perceive themselves as less vulnerable to criticism, rejection, and attacks from others (Gilbert, 2003).

The aforementioned associations were identified for both parents, supporting the importance of assessing the role of fathers and mothers as safe haven and secure base (Kerns et al., 2015). However, our results suggest that adolescents’ perceptions of mothers as safe haven tended to have stronger associations with internal shame than adolescents’ perceptions of fathers as safe haven. These findings appear to be consistent with the idea that mothers are often seen more as safe haven providers (Grossman & Grossman, 2020) compared to fathers. Given this expectation toward the maternal figure, adolescents who perceive higher levels of confidence in their mother’s availability to provide them guidance and assistance in distressing situations (Kerns et al., 2015) may have more positive expectations about the self, perceiving themselves as less inferior, inadequate, undesirable, empty or isolated (Gilbert, 2003). In contrast, the strength of the associations between perceived secure base in the relationship with both parents and shame (internal, external, total) appear to be comparable. Given the centrality of the acquisition of autonomy during early adolescence (Reimer, 1996), the support of both parents in adolescents’ exploration of new interests and expression of personal ideas (Kerns & Brumariu, 2016) may be important and may be associated with the way how adolescents self-evaluate and perceive themselves as vulnerable to the attacks from others.

This study has some limitations. First, participants were recruited in an urban Portuguese school, using a convenience sampling method. The enrollment rate was 54% and most adolescents in our sample attended the 5th and 6th grades, living in intact families. Furthermore, most parents held a university degree and were employed. Overall, sample recruitment and composition limit its representativeness and, consequently, the generalizability of the findings. Second, data collection only relied on self-report questionnaires. Self-report questionnaires have the advantage of being easy to administer but are vulnerable to social desirability bias. Lastly, this study was based on a cross-sectional design, so it is not possible to establish causal relationships between the study variables or to draw conclusions on the direction of the associations between the variables.

Future studies need to be conducted in more diverse samples in terms of sociodemographic and geographical characteristics, using a multi-method approach (e.g., attachment narratives, interviews with vignettes to assess shame, questionnaires), multiple informants (e.g., parents, teachers, peers) and longitudinal designs. Research needs to examine stability and change in the associations between attachment to both parents and shame (internal, external, and total) throughout adolescence. Furthermore, the potential role of individual (e.g., adolescents’ emotional regulation and social competence), family (e.g., inter-parental conflict) and social factors (e.g., friendship quality, peer victimization) need to be explored to explain and understand more in-depth the associations between perceived attachment to both parents and self-reported shame in adolescence.

From an intervention standpoint, our findings suggest that family-centered interventions that promote the modification, flexibilization and restructuring of the representations that adolescents hold about their parents as safe haven and secure base may be important to minimize disruptive feelings of internal, external, and global shame. These findings also support the importance of early intervention with parents to promote healthy parent-child relationships that can prevent negative outcomes in the way how children and adolescents self-evaluate themselves and perceive others.