Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Portuguesa de Saúde Pública

versão impressa ISSN 0870-9025

Rev. Port. Sau. Pub. vol.34 no.2 Lisboa jun. 2016

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsp.2015.07.006

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Safety climate in the operating room: Translation, validation and application of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire

Clima de segurança no bloco operatório: tradução, validação e aplicação do Questionário de Atitudes de Segurança

João Pedro Alexandre Pinheiro a, b, *, António de Sousa Uva c, d

a Departamento de Radiologia, Escola Superior de Saúde, Universidade do Algarve, Avenida Dr. Adelino da Palma Carlos, 8000-510 Faro, Portugal

b CES – Centro de Estudos em Saúde da Universidade do Algarve, Portugal

c Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Avenida Padre Cruz, 1600-560 Lisboa, Portugal

d CISP – Centro de Investigação em Saúde Pública, ENSP/UNL, Lisboa, Portugal

ABSTRACT

Background

Safety climate assessment is increasingly recognized as an important factor in healthcare quality improvement, especially in operating rooms (OR). One of the most commonly used and rigorously validated tools to measure safety culture is the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ). This study presents the validation of the Operating Room Version of the SAQ (SAQ-OR) for use in Portuguese Hospitals. The psychometric properties of the translated questionnaire are also presented.

Methods

The original English version of the SAQ-OR was translated and adapted to the Portuguese setting by forward–backward translation method and applied in a central public hospital. Scale psychometrics were analyzed using Cronbach's alpha and inter-correlations among the scales.

Results

The internal consistency test yielded values around 0.9 for all 73 items. The CFA and its goodness-of-fit indices (SRMR 0.05, RMSEA 0.002, CFI 0.90) showed an acceptable model fit. Inter-correlations between the factors safety climate, teamwork climate, job satisfaction, perceptions of management, and working conditions showed moderate correlation with each other. 82 valid questionnaires were analyzed revealing significant differences in communication ratings between different jobs, mainly between surgeons (4.2) and between nurses and surgeons (2.9). Working conditions and job satisfaction have the highest score with 3.8 and 3.5, respectively, and perceptions of management have the lowest score (2.8).

Conclusion

The Portuguese translation of the SAQ-OR reveals good psychometric properties for studying the organizational safety climate, however larger and further studies are required to compensate the lack of subjects in some items. Like other studies, this scale seems to be an acceptable to adequate tool to evaluate the safety climate. Results allowed to conclude that working conditions and job satisfaction are satisfactory. However, there is latitude for improvement, especially in the involvement of the management bodies as this factor has the lowest score for the majority of healthcare professionals.

Keywords: Safety climate. Operating room. Ergonomics. Patient safety. Healthcare quality.

RESUMO

Introdução

A avaliação do clima de segurança é cada vez mais reconhecida como um fator na melhoria da prestação de cuidados de saúde, especialmente no bloco operatório (BO). Um dos instrumentos mais comumente validados e utilizados para medir a Cultura de Segurança é o Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) ou Questionário de Atitude de Segurança (QAS). Este estudo apresenta a validação da versão para Bloco Operatório (QAS-BO), para aplicação nas instituições de saúde portuguesas. As características psicométricas do questionário traduzido são também apresentadas.

Metodologia

A versão original em inglês do QAS-BO, foi traduzida e adaptada para o contexto português, através do processo de tradução-retradução e aplicado num hospital público central. A análise psicométrica foi feita através do alfa de Cronbach e das correlações entre escalas.

Resultados

Os testes de consistência interna obtiveram valores médios de 0.9 para os 73 itens. A análise fatorial e o grau de ajuste (SRMR 0.05, RMSEA 0.002, CFI 0.90) obtiveram valores satisfatórios. As relações entre o clima de segurança, trabalho em equipa, satisfação profissional, perceção sobre os órgãos de gestão e condições de trabalho são moderadas. Um total de 82 questionários foram analisados e revelaram diferenças significativas na comunicação entre diferentes classes profissionais, nomeadamente entre cirurgiões (4.2) e entre cirurgiões e enfermeiros (2.9). As condições de trabalho e a satisfação profissional obtiveram os valores mais elevados, com 3.8 e 3.5 respetivamente, e a perceção sobre os órgãos de gestão o valor mais baixo (2.8).

Conclusão

A versão portuguesa do QAS-BO, apresenta boas características psicométricas para estudar o clima de segurança das instituições de saúde, não obstante, são necessários estudos mais abrangentes de forma a colmatar o reduzido número de elementos em alguns itens. Tal como outros estudos revelaram, este instrumento é aceitável para analisar o clima de segurança. Os resultados permitem concluir que as condições de trabalho e a satisfação profissional são satisfatórias. No entanto, existe oportunidade de intervenção e melhoria, principalmente no envolvimento dos órgãos de gestão.

Palavras-chave: Clima de segurança. Bloco operatório. Ergonomia. Segurança do doente. Qualidade em saúde.

Introduction

Population based research suggests that in the United States between 44,000 and 98,000 patients die each year from preventable errors, making medical error the eighth most common cause of death.1 Operating rooms (OR) can have a high prevalence of errors, being an interdisciplinary, complex activity with a strong dependence on technical skill, where ergonomics and organizational factors play an essential role. Due to these factors it is imperative that the safety climate in the OR is analyzed in order to improve patient safety.2 Efforts to assess and improve safety culture and to better define its role in patient safety are facilitated by its measurement. By identifying attributes of an organization that are both malleable and potentially related to safety, managers can intervene to improve the quality of care. Existing patient safety climate measurement tools are numerous, whereas little information in the literature provides guidance to users or researchers in the selection of tools for research or safety improvement measurement initiatives.3

Patient safety is fundamental to healthcare quality. Attention has recently focused on the patient safety climate of an organization and its impact on patient outcomes. A strong safety climate appears to be an essential condition for safe patient care in hospitals. A number of instruments are used to measure this patient safety climate or culture. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) is a validated, widely used instrument to investigate multiple factors of safety climate at the clinical level in a variety of inpatient and outpatient settings.4 Variations on the definition of safety culture exist.5 “Safety culture” and “safety climate” are sometimes used interchangeably, but in the literature, different meanings tend to be given to the terms. Measuring safety culture or safety climate is important because the culture of an organization, team perceptions influence patient safety outcomes, and these measures can be used to monitor changes over time.6 The safety culture is part of the overall culture of an organization.7 This refers to how patient safety is designed and implemented within an organization and the structures and processes to support them.8 Safety culture became popular after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986, when it was suggested that organizations can reduce accidents and safety incidents through the development of a “positive safety culture”.9 Therefore, the concept of safety culture is not unique to healthcare, and has been widely used in the oil industries, gas and energy, transport, aviation and military sectors.10 The “safety culture” is broadly defined as: “a global phenomenon that spans the norms, values and basic assumptions of a whole organization. Climate, on the other hand, is more specific and refers to professional perception of particular aspects of the organization's culture”.11 Compared to safety climate, culture is a broader term that represents all aspects and values of an organization as well as actions related to safety, while the climate focuses more on the perception that professionals have about how safety is managed in organizations.12 Safety climate has been defined as “the way we do things around here,” or perceptions of policies, practices and “shared” procedures.13 As such, the safety climate-spectrum describes an organization that is influenced by how people behave, think and feel about safety issues. This is a complex phenomenon that is not always understood by the leaders of healthcare institutions, thus making it difficult to operationalize, and essential leadership experience to achieve a climate of safety throughout the organization.14 In this view, the safety culture is a broad term that represents all aspects and values of an organization as well as actions related to security,12 while safety climate is a subset of the broader culture and refers to perceptions health professionals on patient safety within the organization.15 For this reason, some authors suggest that it is easier to measure safety climate, because culture is much broader.7 This focuses more on perceptions of security professionals regarding support for the management, supervision, risks, policies and practices of security, trust and openness.

Concerning operating rooms teams are composed by three different careers (surgery, anesthesiology and nursing) with intermittent representations by radiology and pathology.16 Action in OR is a complex, interdisciplinary practice, with heavy reliance on individual action (human technical skills), held within complex organizations where human and team factors (human non-technical skills) and organizational factors (system) play a key role in a constant interaction between humans, machines and equipment.2 The OR in the logic of the open environment system receives various inputs and through a set of activities, transforms resources (inputs) into results (outputs)17 and is sensible to external influences on performance and group dynamics.18 The environment of the operating room, by its very nature, is conducive to accidents and teamwork and cooperation is critical to the efficiency and above all for safety in surgery and its deficit is responsible for about half of errors detected.2

Methods

The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire-Operating Room version

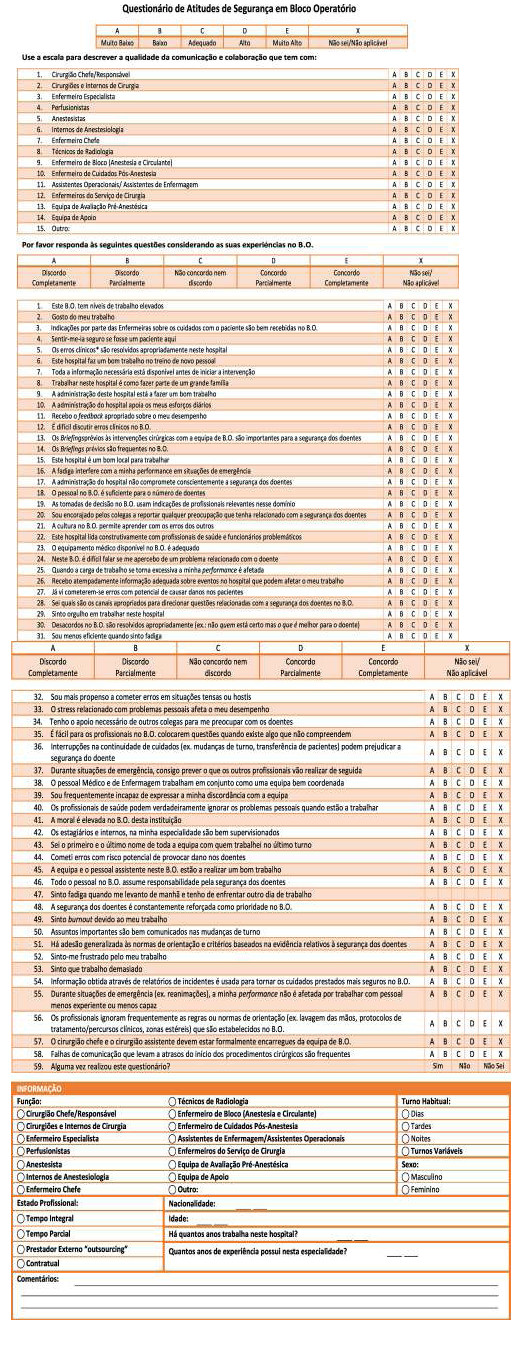

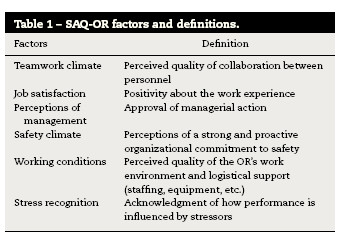

The SAQ was developed to measure attitudes regarding safety climate. The SAQ is a refinement of the Intensive Care Unit Management Attitudes Questionnaire19 and the full version of the SAQ comprises 60 items, whereas the OR version contains 59 items, with 30 belonging to six factors: teamwork climate, job satisfaction, perceptions of management, safety climate, working conditions, and stress recognition20 (Table 1). The questionnaire takes approximately 10–15 min to complete and each item is answered using a 5-point Likert scale (Disagree Strongly, Disagree Slightly, Neutral, Agree Slightly, Agree Strongly).21

Translation of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire-Operating Room (phase 1)

The questionnaire was translated from the original in English using the forward–backward translation method. The EN-PT translation is performed by two independent translators (A – Portuguese person with knowledge of English and B – English person with knowledge of Portuguese), in which the first performed the translation and the second carried out the verification of that translation. A translator C (English person with knowledge of Portuguese) translated the Portuguese version of the questionnaire back to English. Finally we compared the original version of the questionnaire (written in English) with the English version of the translator. The equality or similarity between these two questionnaires indicates whether the Portuguese version of the questionnaire is suitable for application.

Face validity (phase 2)

Before using the instrument in a sample of healthcare professionals, a pre-test was performed to validate, check the instrument effectiveness and make any corrections. The face validity was tested by 4 nurses and 4 physicians, randomly selected from the OR team with different ages and specialties. They studied the Portuguese version and were guided to indicate concerns about the items and feel free to propose a better formulation. Comments were then discussed by the researchers and a consensus was reached and a final translated SAQ-OR Portuguese version was established.

Psychometric testing of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire based on survey data

A cross-sectional design was used to test the internal consistency of the SAQ-OR. Surgeons, Nurses, Anesthesiologists, Radiographers and Auxiliaries with at least 1 year of working experience at a central hospital from two surgical wards were asked to fill out the Portuguese translation of the SAQ-OR. Respondent demographic characteristics such as gender, age, professional category, professional experience, employment status were also included.

Data collection and ethical considerations

The questionnaires were distributed to the Surgeons, Nurses, Anesthesiologists, Radiographers and Auxiliaries by the head nurse and head Anesthesiologist or the researcher and had to be completed within 2 months. All questionnaires were collected in a (secured) box on the ward. Every week, a reminder was sent to ward staff. Respondents were informed that participation was voluntary. Questionnaires were treated anonymously, and that the decision to return a completed questionnaire was deemed their informed consent. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Algarve's Hospital Center (Centro Hospitalar do Algarve – CHA).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the population characteristics and the SAQ-OR item and scale-level results on the units. Internal consistency of the total SAQ-OR and its six factors “teamwork climate,” “safety climate,” “stress recognition,” “working conditions,” “job satisfaction” and “perception of management” was measured by calculating Cronbach's alpha.

The goodness-of-fit statistic was used to measure whether the overall model fit was good. Three different fit indices were used: standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and comparative fit index (CFI). The goodness-of-fit statistics and correlation matrix were analyzed with IBM SPSS AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures) V.22.22

A good model fit between the target model and the observed data are distinguished by SRMR values between 0.0 and 1.0, where 0.0 indicates perfect fit, and RMSEA values ≤ .05 and CFI values ≥ .95.21 Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used for conclusions about the conceptual and semantic equivalence of a translated questionnaire20 and deals with the relationships between observed measures or indicators. In this context, CFA is used to verify the number of underlying factors of the instrument and the pattern of item–factor relationships (factor loadings).22

Normality test was performed using the Kolmogorv–Smirnov test. Data analysis was performed by frequency tables and descriptive statistics. In order to compare more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test (H) was performed. Finally, for a review of the relationship between variables, the Spearman correlation (rs) test was applied. All data were analyzed using SPSS (version 20.0 for Windows).

Results

Translation, validity and internal consistency of Safety Attitudes Questionnaire-Operating Room

Translation of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire-Operating Room (phase 1)

No significant differences were detected between the translations. Ethnic group was present in the demographics section of the English version of the questionnaire, but was decided to be removed as it was considered to be irrelevant and still possibly offensive. Some questions were considered somewhat delicate, because of the sensitivities regarding errors, staffing, management, and workload.

Face validity (phase 2)

No major remarks were given by the four nurses and four physicians who evaluated the face validity of the SAQ-OR. Minor suggestions were given to improve the clarity of the wording, e.g. the word “medical error” was changed to “clinical error” (“erro médico” to “erro clínico”) as the term “medical error” in Portuguese implies that these are errors performed by physicians alone and not by all healthcare professionals. Moreover a brief definition of what was considered a “clinical error” was included on the bottom of the questionnaire similar to the original English version (“Clinical error is defined has any mistake in the delivery of care, by any healthcare professional, regardless of the outcome”). In addition, one spelling mistake was detected and corrected (“fatigue” was translated to “fatiga” instead of “fadiga”) (Annex 1).

Psychometric testing of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire based on survey data

The sample consists of 82 healthcare professionals who hold positions in the operating room, divided into 5 distinct professional classes. 18 surgeons (22%), 43 nurses (52%), 11 anesthesiologists (13%), 6 (7%) Radiographers and 4 auxiliaries (5%). 21 subjects have ages between 20 and 29 years (25.6%), 26 between 30 and 39 years (31.7%), 18 between 40 and 49 years (22%), 14 between 50 and 59 years (17%) and 3 between 60 and 69 years (3.7%).

We obtained a mean age of 38.7 years, a minimum of 23 years and a maximum of 61 years. The average number of years that health professionals working in that institution is 12.6 years with 10.1 years of professional experience with a minimum of 1 year and a maximum of 36 years, respectively. Regarding the sex distribution of the sample, 44 were female (53.7%) and 38 male (46.3%). Of all surgeons, 15 were males. With a total of 43 nurses, the majority (n = 27) were females.

The majority of respondents are between 0 and 5 years working in the institution with 24%, and between 6 and 10 years with 28%. The same applies to years of experience with 34.1% and 31.7% respectively. The majority of the sample is employed full time (91.5%) and only 7 elements claim to be hired part-time or contractual. Regarding shifts performed, most of the staff said they hold variable shifts (73.2%).

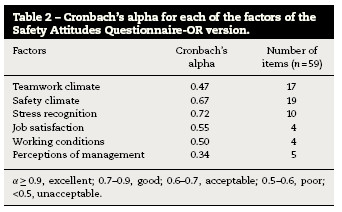

Internal consistency

In order to study the internal consistency of the instrument used, Cronbach's alpha for each of the factors of the questionnaire was calculated (Table 2). The overall Cronbach's alpha assumes a value of 0.89 for all items of the questionnaire which is borderline excellent.

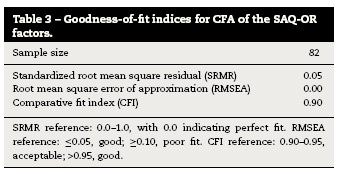

Internal construct validity

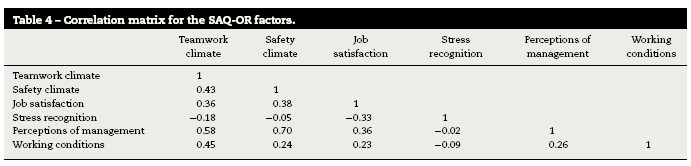

The goodness-of-fit values used to evaluate the internal construct validity are displayed in Table 3. The SRMR value was 0.05, the RMSEA was 0.00, and the CFI value was 0.90, which indicates an acceptable model fit approximation of the translated version of the SAQ-OR. The inter-correlations between the factors are presented in Table 4 and ranged from 0.2 to 0.7.

Communication

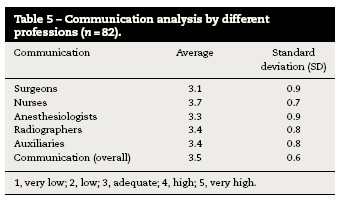

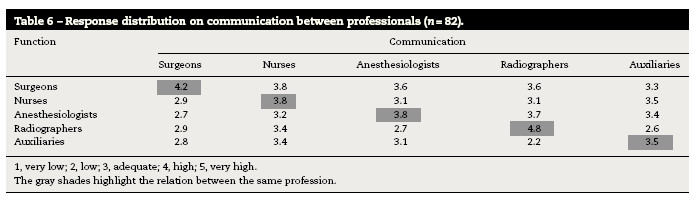

Based on a Likert scale of 6 points the sample classified the quality of communication. Descriptively represented in Table 5 are the averages of the responses for the different professions and in Table 6 about communication between professional groups.

In order to ascertain whether the respondent's occupied function produces some influence on their perception of communication, the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis (H) (Table 7) was applied.

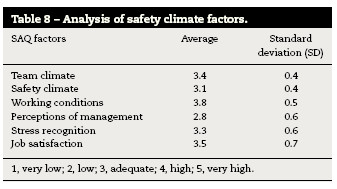

Safety Attitudes Questionnaire-operating room factors

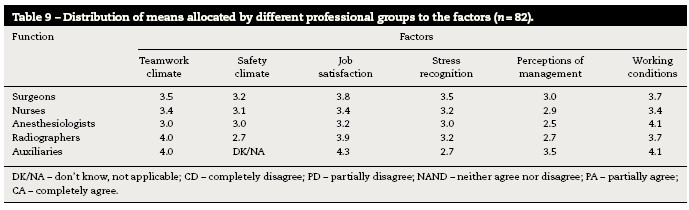

In Table 8 are shown the factors of the instrument that comprise safety climate. Working conditions is the factor that has a higher average (3.8) and perceptions of management have the lowest average (2.8). The climate team also has a high value in relation to other factors, however is considerably within the average (3.4). Still related to this factor the safety climate has the second lowest rating with 3.1 in average.

A table with their respective response averages attributed by caregivers to each factor groups was also made (Table 9). The factors with higher scores are the working conditions and job satisfaction.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to translate the SAQ-OR Version and assess the validity and reliability of the Portuguese version. The values obtained in the study of validity of the instrument both in each factor and as a whole are of the same magnitude of the figures presented by the authors of the questionnaire.19 Translations and adaptations of “Safety Attitudes Questionnaire” for other languages also revealed a high content validity.23,24 The SAQ has also been extensively used to relate climate safety with the results for the patient,24 however this study did not address this issue. The present value of Cronbach's alpha value is closely linked to the number of items evaluated. The greater the number of items, the higher the alpha value obtained.25 Thus, it is possible to determine that low values are caused by the small number of items per factor.26 Despite the usefulness of Cronbach's alpha in the study of reliability, it is still an estimate, subject to many influences to be taken into account. The alpha value is not a characteristic of the instrument, but rather an estimate of the reliability of the data obtained,27 however, the values recorded on the validity of the instrument, using Cronbach's alpha ranged between 0.68 and 0.90.21,23,25 This study was conducted in a public hospital, more specifically in the surgery department. Many studies which use the SAQ have samples within the hundreds or even thousands of subjects as they are large-scale studies.5,20,28 Internal construct validity based on the CFA and goodness-of-fit indices (SRMR, RMSEA, and CFI) showed an acceptable model fit. According to good model fit indices, the Portuguese version of the SAQ-OR is a valid instrument. Factors were moderately correlated except for stress recognition, similar to the results of the psychometric testing of other versions of the SAQ-OR.20,21

The main elements of the operating room team are surgeons, nurses and anesthesiologists. Radiographers just add some timely interventions, particularly in orthopedics or cardiology,16 being called by the radiology department, and therefore not part of the surgical team itself. So this professional class has also been included for the sake of consistency as indirectly involved with patient safety in the operating theater. There are significant differences related to communication between the operating room team. Nurses also have the highest average (3.8) which suggests higher quality of communication between them and the other professions which agrees with studies using the same instrument29 followed by Auxiliaries (3.4), Radiographers (3.4) and Anesthesiologists (3.3). Surgeons have the lowest average (3.1). Communication in the operating room follows complex patterns and is influenced by recurrent themes causing tension.16 These results however, should not be extrapolated or generalized because they are very dependent on the number of individuals present in each professional group. Nevertheless, similar studies point to similar results in different patterns and professional classes have different communication strategies.26,27,30 Observational studies report more tense patterns of communication between surgeons and nurses.31 Communication patterns between tense surgeons and anesthesiologists were also observed, but uncommon.16,27 This can be explained by the fact that the procedures for dialog are more common among surgeons and nurses. In a study in which they used questionnaires and direct observation of surgical procedures, nurses describe good partnership as having their opinions respected and accepted in the OR and the surgeons describe good collaboration when nurses anticipate their needs and follow their instructions.32 In another study conducted in an intensive care unit with similar methodology, doctors often resorted to nurses to provide additional information and further details on the evaluation of the patient during rounds.33 However, they describe many difficulties and less involvement in decision making process during the rounds.

The factors “safety climate” and “perception of management” obtained the lower averages (3.1 and 2.8 respectively) and job satisfaction and working conditions the higher (3.5 and 3.8 respectively). Regarding the distribution of the average response of different professional groups evidenced that surgeons and radiographers have the highest job satisfaction (3.8 and 3.9). Nurses give greater score to team climate (3.4) and working conditions (3.4). Anesthesiologists give higher score to fatigue and stress than other professional groups, followed by surgeons (3.5) and nurses (3.2). Compared to the studies analyzed, nurses have higher levels of stress, followed by anesthesiologists and surgeons.5,28,34 The instrument used is derived from a questionnaire for aviation safety. There is overlap between the two items of about 25%. In a comparative study, the size of teams between OR and aviation demonstrated that the pilots had less tendency to negate the effects of fatigue and stress on your performance against surgeons (26% versus 70%).34 Being collaboration and communication as important to the success of the procedures, the SAQ allows to measure teamwork, identify problems within and between professional groups and evaluate interventions aimed at improving patient safety.16 Other authors have concluded that, as in aviation, errors are more related with non-technical skills such as communication, than with the technical capacity and performance.2,18

Conclusions

The SAQ-OR demonstrates good psychometric capabilities to study safety climate, however larger studies are needed to address the lack of data on some items. The development of a valid and reliable instrument is a longitudinal process that requires numerous positive findings across different settings. The results indicate that working conditions and job satisfaction are acceptable, but it is crucial to improve the safety climate and the involvement of the management bodies. Improving safety climate is crucial for increasing quality of service on surgical wards, and thus, it becomes relevant to improve the above aspects. Our results demonstrate the perception of professionals employed in the OR, but the use of interviews and direct observation of surgical procedures, would be also interesting for a more suitable approach.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, (1999) . [ Links ]

2. Fragata J. Erros e acidentes no bloco operatório: revisão do estado da arte. Rev Port Saúde Pública. 2011;Vol Temat(10):17-26. [ Links ]

3. Singla A., Kitch B. Assessing patient safety culture: A review and synthesis of the measurement tools [Internet]. J Patient Saf. 2006;2:105-16. [ Links ]

4. Devriendt E., Heede K., Van J., Dejaeger E., Sexton B., Wellens N.I.H., et al. Content validity and internal consistency of the Dutch translation of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: An observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:327-37. [ Links ]

5. Nordén-Hägg A., Sexton J.B., Kälvemark-Sporrong S., Ring L., Kettis-Lindblad A. Assessing safety culture in pharmacies: The psychometric validation of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) in a national sample of community pharmacies in Sweden [Internet]. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2010;10:8. [ Links ]

6. National Healthcare System. An introduction to safety climate. London: National Healthcare System, (2010) . [ Links ]

7. Ross J. Patient safety outcomes: The importance of understanding the organizational culture and safety climate. J Perianesth Nurs. 2011;26:347-8. [ Links ]

8. Turnberg W., Daniell W. Evaluation of a healthcare safety climate measurement tool. J Safety Res. 2008;39:563-8. [ Links ]

9. Findley M., Smith S., Gorski J., O’Neil M. Safety climate differences among job positions in a nuclear decommissioning and demolition industry: Employees’ self-reported safety attitudes and perceptions [Internet]. Saf Sci. 2007;45:875-89.

10. Flin R. Measuring safety culture in healthcare: A case for accurate diagnosis [Internet]. Saf Sci. 2007;45:653-67. [ Links ]

11. Blegen M., Pepper G., Rosse J. Safety climate on hospital units: A new measure. Advances in patient safety. Volume 4: Programs, tools, and products., Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2012. [ Links ] .

12. The Health Foundation Inspiring Improvement. Evidence scan: Measuring safety culture [Internet]. London: The Health Foundation; 2011. Available from: http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/MeasuringSafetyCulture.pdf [accessed 08.12.12].

13. UK. Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Offshore Safety Division. Safety climate measurement: User guide and toolkit [Internet]. London: Health and Safety Executive; 2004. Available from: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/media/wwwlboroacuk/content/sbe/downloads/Offshore%20Safety%20Climate%20Assessment.pdf [accessed 15.01.13].

14. Sammer C., Lykens K., Singh K.P., Mains D.A., Lackan N.A. What is patient safety culture?: A review of the literature. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42:156-65. [ Links ]

15. Flin R., Burns C., Mearns K., Yule S., Robertson E.M. Measuring safety climate in health care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:109-15. [ Links ]

16. Lingard L., Reznick R., Espin S. Team communications in the operating room: Talk patterns, sites of tension, and implications for novices [Internet]. Acad Med. 2002;77:232-7. [ Links ]

17. Pereira MCA. Dinâmicas e percepções sobre trabalho de equipa: um estudo em ambiente cirúrgico. Covilhã: Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde. Universidade da Beira Interior; 2010. Mestrado Integrado em Medicina.

18. Helmreich R., Schaefer H. Team performance in the operating room. New Jersey: Hillsdale, (1994) . [ Links ]

19. Sexton J., Thomas E. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire [Internet]. Austin: University of Texas, (2011) . [ Links ]

20. Göras C., Wallentin F.Y., Nilsson U., Ehrenberg A. Swedish translation and psychometric testing of the safety attitudes questionnaire: Operating room version [Internet]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:104. [ Links ]

21. Sexton J., Helmreich R., Neilands T., Rowan K., Vella K., Boyden J., et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: Psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research [Internet]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:44. [ Links ]

22. Brown T.A. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, (2006) . [ Links ]

23. Deilkås E.T., Hofoss D. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ): generic version: Short Form 2006 [Internet]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:191. [ Links ]

24. Devriendt E., Van K., Coussement J., Dejaeger E., Surmont K., Heylen D., et al. Content validity and internal consistency of the Dutch translation of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: An observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:327-37. [ Links ]

25. Shteynberg G, Sexton BJ, Thomas EJ. Johns Hopkins Quality and Safety Research Group. Test retest reliability of the safety climate scale. Austin: The University of Texas Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research and Practice; 2005. Technical Report; 01-05.

26. Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 3rd ed., Los Angeles: Sage, (2009) . [ Links ]

27. Maroco J., Marques G. Qual a fiabilidade do alfa de Cronbach? Questões antigas e soluções modernas?. Lab Psicol. 2006;4:65-90. [ Links ]

28. Makary M., Sexton J., Freischlag J.A., Holzmueller C.G., Millman E.A., Rowen L., et al. Operating room teamwork among physicians and nurses: Teamwork in the eye of the beholder. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:746-52. [ Links ]

29. Wisniewski A.M., Erdley W.S., Singh R., Servoss T.J., Naughton B.J., Singh G. Assessment of safety attitudes in a skilled nursing facility. Geriatr Nurs. 2007;28:126-36. [ Links ]

30. Hill A., Hill M. Investigação por questionário. Lisboa: Sílabo, (2002) . [ Links ]

31. Gardezi F., Lingard L., Espin S., Whyte S., Orser B., Baker G.R. Silence, power and communication in the operating room [Internet]. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:1390-9. [ Links ]

32. Lingard L., Whyte S., Espin S. Communication failures in the operating room: An observational classification of recurrent types and effects. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:24. [ Links ]

33. Manias E. Street A. Nurse–doctor interactions during critical care ward rounds. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10:442-50.

34. Sexton J., Thomas E., Helmreich R. Error, stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: Cross sectional surveys. Br Med J. 2000;9:745-9. [ Links ]

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Chief-Nurse Maria Manuela and the OR board of the Centro Hospitalar do Algarve (CHA-Faro) for their cooperation.

*Corresponding author: jppinheiro@ualg.pt, joao.pinheiro88@gmail.com

Received April 19, 2015. Accepted July 28, 2015

ANNEX

Annex 1. Safety Attitudes Questionnaire-Operating Room–Portuguese Version.