INTRODUCTION

Plants of the genus Atriplex are popular because they are used in phytoremediation programs in several regions of the globe (Calone et al., 2021, Ahmadi et al., 2022). Their cultivation ranges from arid environments with salinity problems to coastal regions. Many of these sites have in common the presence of salts at high concentrations in soil and different water regimes. However, they differ with respect to the incidence of light radiation (Falasca et al., 2014; Melo et al., 2017; Alharby et al., 2018; Tawfik et al., 2019).

Among the abiotic factors that interfere in plant development, solar radiation is one of the most important with regard to photosynthesis performance, as it affects plant growth and yield. Different climatic zones have different light intensities or show variations according to the seasons (Khalifa et al., 2018). Therefore, photosynthesis performance can vary greatly depending on the amount and duration of light interception (Zhang et al., 2022).

The photosynthetic performance of A. nummularia has been extensively investigated in warm-climate countries of South America (De Tafur et al., 1997; El-Sharkawy and Tafur, 2010; El-Sharkawy et al., 2012). However, a detailed description of photosynthesis x irradiance curves of this species in response to the increase of NaCl in irrigation water remains unexplored, leading to lack of information on its tolerance to high light intensities or acclimation to irradiance.

Variations observed in photosynthesis curves in response to different light intensities can be reliably used to indicate the photosynthetic performance of plants under different conditions of abiotic and biotic stress, including stresses by light (Park et al., 2020), nutrients (Lachapelle and Shipley, 2012), competition (Gao et al., 2015), disease (Habermann et al., 2003), pollution (Lin et al., 2015) and salinity (Geissler et al., 2015).

Soil salinity, in turn, is one of the main abiotic stresses that affect crop yield as it reduces growth and affects different physiological functions of plants, especially those of agronomic interest (Kalaji et al., 2016). However, thanks to the development of various mechanisms at the cellular and molecular level responsible for protecting the photosynthetic apparatus from salinity throughout the evolution, halophytes are able to develop even in environments with high concentrations of salts (Rozentsvet et al., 2017).

Atriplex nummularia, for example, is a xerohalophyte species widely used in studies aimed at the recovery of salt-degraded areas due to its phytoremediation potential (Souza et al., 2014; Cunha et al., 2017; Lam et al., 2017; Miranda et al., 2018). For some years, research groups have been striving to understand the physiological mechanisms that enable the high performance of this species in environments degraded by salinity (Silveira et al., 2009; Souza et al., 2012, 2014; Melo et al., 2016, 2017; Lins et al., 2018). Nevertheless, data on the physiological responses of this species to different light intensities are scarce, especially those related to the damage caused by the osmotic and ionic effects on the photosynthetic apparatus.

In general, the effect of salts on the plant occurs in two main distinct phases: a rapid response to the increase in osmotic pressure of the soil solution that is independent of the nature of the ions involved and can occur from minutes to days; and a second phase, which in turn occurs over a period of days to weeks and is related to a slower response associated with the effects of accumulation of sodium and chloride ions at toxic concentrations in the shoots (De Souza et al., 2013; Coelho et al., 2014)

In halophyte plants the protection of the photosynthetic apparatus can also occur through heat by means of the xanthophyll cycle, which is considered the first line of defense against damage caused by excessive excitation energy or by the consumption of excess electrons in the photosystem I (PSI) by the water cycle. Another way to prevent excessive reduction of the electron transport chain and protect other components of photochemistry is through the inactivation of photosystem II (PSII) (Jaleel et al., 2007; Taiz and Zeiger, 2015). In studies aimed at investigating the physiological responses of plants to the effects of salt stress, it is common to evaluate photosynthesis, given the known deleterious effect of salts on the photosynthetic apparatus of plants. In general, these evaluations are performed using equipment that quantifies gas exchange, such as IRGA, at a fixed photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) around 1500 μmol m-2s-1.

Considering that most halophytes evolved in environments characterized by high luminosity, a large number of studies may be generating underestimated values of photosynthetic rates and mistakenly attributing them to salinity. For these reasons, the objective of this study was to investigate the photosynthetic efficiency of A. nummularia under a wide range of salt concentration in irrigation water by constructing light curves in vivo in order to identify and indicate the best range of photosynthetically active radiation that should be used in research studies involving the performance of this species under salinity.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Plant material and stress conditions

Atriplex nummularia plants were propagated by cuttings, using a single plant as parent, in order to minimize genetic variability. Cuttings of approximately 12 cm were placed to root in a protected environment in polyethylene tubes containing washed sand.

Plantlets aged two months completely rooted and acclimated were transplanted to pots with 5 L capacity containing soil. During the entire experimental period, the plants were cultivated in soil with moisture content corresponding to 80% of the pot capacity. The saline treatment began to be applied 15 days after transplantation. Irrigation was always carried out in the late afternoon, replacing the water lost by evapotranspiration, using irrigation waters with six different concentrations of NaCl (0, 50,100, 200, 250 and 300 mmol L-1), in four replications

Irrigation with the saline waters was performed gradually to prevent the plants from suffering osmotic shock, so the saline treatments were established through the addition of a 50 mmol L-1 NaCl solution until the concentration of the respective treatment was reached.

Experimental Configuration

The present study was conducted in a protected environment located in the Department of Agronomy (DEPA), at the main campus of the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (UFRPE), whose coordinates are 8º01’00” South latitude, 34º59’40” West longitude. During the experiment, the average temperature and relative humidity in the greenhouse were 28.59 º C and 70%, respectively.

The experiment was conducted using polyethylene pots with 5 L capacity filled with soil classified as Fluvisol (IUSS Working Group WRB, 2015), collected in the municipality of Pesqueira - PE. The soil collection site is located on Nossa Senhora do Rosário farm, whose coordinates are 8° 34’11” South latitude, 37°48’54” West longitude and is located at 630 m above sea level. According to Köppen’s classification, the climate of the soil collection region is BSh (extremely hot and semi-arid), with total annual average precipitation of 730 mm and average annual reference evapotranspiration of 1.683 mm.

The soil was collected in the 0-30 cm layer, air-dried, pounded to break up clods and sieved through a 4-mm mesh to preserve microaggregates and subsequently fill the pots. For chemical characterization (Table 1), ten individual samples of the total soil volume were collected and sieved through a 2 mm to obtain air-dried fine earth (ADFE). The value of the initial characterization refers to an average of ten samples.

Table 1 Mean values (n=10) of the chemical characteristics of the saturation extract, sorption complex and physical characteristics of the soil used for the cultivation of Atriplex nummularia under different salinity levels

| Characteristics | Value |

| Saturation extracta | |

| pH | 7.77 |

| Electrical Condutivity (dS/m) | 2.17 |

| Na+ (mmol/L) | 13.26 |

| K+ (mmol/L) | 1.83 |

| Ca+2 (mmol/L) | 3.15 |

| Mg+2 (mmol/L) | 1.36 |

| Cl- (mmol/L) | 14.37 |

| Sodium adsorption ratio | 8.5 |

| Exchangeable complex a | |

| pH (1:2.5) | 6.85 |

| Na+ (cmolc /kg) | 1.64 |

| K+(cmolc /kg) | 3.7 |

| Ca+2(cmolc /kg) | 7.78 |

| Mg2+(cmolc /kg) | 1.73 |

| Sum of bases (cmolc /kg) | 14.85 |

| Exchangeable sodium percentage (%) | 11.07 |

| Physical characteristics b | |

| Fine sand (g/kg) | 435.00 |

| Coarse sand (g/kg) | 17.00 |

| Silt (g/kg) | 386.00 |

| Clay (g/kg) | 162.00 |

| Soil bulk density (g/cm3) | 1.36 |

| Soil particle density (g/cm3) | 2.66 |

| Total porosity (%) | 49.57 |

a USSLS (1954); b (EMBRAPA, 1997).

Light curves

Carbon assimilation responses were evaluated when plants were subjected to different levels of Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) incident on the leaf surface, using PAR variation between 0 and 2000 μmol photons m-2 s-1 (0, 5, 10, 15, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 175, 200, 250, 500, 750, 1000, 1250, 1500, 1750, 2000). This evaluation was performed at 15 and 84 (DAT) using a portable Infrared Gas Analyzer (IRGA), LICOR Li-6400 model, from 9 am to 11 am.

Prior to the incidence of the highest PAR, the leaf was subjected to light acclimation at 500 μmol photons m-2 s-1 for 5 minutes. CO2 concentration, block temperature and relative humidity were 400 μmol m2 s-1, 27 ºC and 50-60%, respectively.

To construct the light saturation curves, plants representative of each treatment were selected and readings were performed on healthy, fully expanded leaves from the middle third. The values of photosynthesis (A) were recorded after the coefficient of variation was lower than or equal to 0.3%, for each PAR variation.

Analysis of the light curve allowed the determination of the maximum photosynthesis rate (Amax), light saturation constant (K), respiration in the dark (Rd), light compensation point (LCP) and photosynthesis efficiency (φ). The values of the respiration rate in the dark (Rd) used to fit the curve were obtained when PAR was 0.0 μmol m-2 s-1.

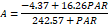

Curve data were analyzed using Statistix software with the data fitted using the Michaelis-Menten model (Michaelis & Mentel, 1913) (Equation 1).

Where: A= Net photosynthesis; Asat = a = Photosynthetic rate at maximum light saturation (Amax); K= b = Light saturation constant (Defined as ½ of saturating PAR); Rd= c = Respiration rate; Light compensation point (LCP) was calculated using Equation 2:

RESULTS

Evaluations of the photosynthetic apparatus responses obtained by means of light curves performed in the plants at 15 DAT demonstrated that, despite the short time of exposure to stress, the increase in NaCl concentration in irrigation water led to significant reductions (p≤0.05) in net photosynthesis, light saturation constant, respiration in the dark and light compensation point (Table 2).

Table 2 Parameters obtained through the equations generated from the light curves at 15 and 84 days after the beginning of the saline treatment

| NaCl (mmol L-1) | Amax (µmol CO2 m-2s-1) | K (µmol m-2s-1) | Rd (µmol CO2 m-2s-1) | LCP (µmol m-2s-1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 DAT | 84 DAT | 15 DAT | 84 DAT | 15 DAT | 84 DAT | 15 DAT | 84 DAT | ||

| 0 | 38.78 a | 9.57 a | 691.98 a | 292.9 a | 5.99 a | 1.21 a | 126.39 a | 42.31 a | |

| 50 | 29.29b | 5.46b | 512.33c | 129.47c | 4.86d | 1.19 a | 102.00c | 36.12b | |

| 100 | 29.07b | 2.30c | 562.12b | 131.76b | 5.18c | 0.08d | 121.90b | 4.66d | |

| 200 | 22.71c | 2.30c | 283.57e | 128.50c | 5.51b | 0.16c | 91.00e | 9.53c | |

| 250 | 16.26e | 0.58d | 242.57f | 22.03e | 4.57e | 0.04e | 94.77d | 1.72e | |

| 300 | 20.95d | 0.94e | 293.15d | 70.76d | 3.94f | 0.31b | 67.80f | 35.06b | |

Amax= Maximum photosynthesis; K= Light saturation constant; Rd= Respiration rate; LCP= Light compensation point; 84 days after the beginning of saline treatment. Means followed by equal letters in columns do not differ from each other by Tukey test, at 0.05% probability level.

At 15 days of evaluation, plants irrigated using water with 50, 100, 200, 250 and 300 mmol of NaCl showed reductions of 24.47%, 41.43%, 58.07%, and 45.97% in photosynthesis compared to those in the control treatment, respectively. The light saturation constant showed a significant reduction (p≤0.05) in response to increasing salinity. Reductions of 64.94% and 57.63% could be observed at NaCl levels 250 and 300 mmol L-1, respectively. The respiration variable showed small reductions in response to the increase of NaCl in irrigation water, with the highest ones observed at the NaCl levels of 250 and 300 mmol L-1 (23.70% and 34.22%), respectively. In regard to the light compensation point, the reductions were around 25%, but plants showed a reduction of ~50% at the NaCl level of 300 mmol L-1.

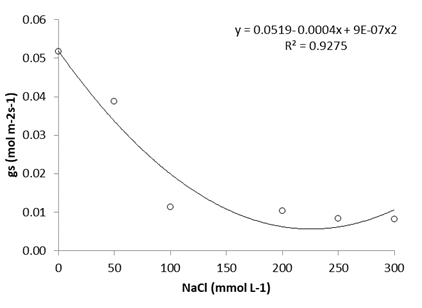

The responses of plants to the variation of different PAR levels, evaluated at 15 days after the beginning of irrigation with saline waters, made it possible to observe that, regardless of the light intensity applied, there was a significant reduction in all parameters derived from the light curve with the increase in NaCl concentration in the irrigation water, and this response was observed from the treatment with 200 mmol L-1 of NaCl (Table 2). However, even plants irrigated using solutions with the highest concentration of NaCl (300 mmol L-1) showed values of photosynthesis considered high (20.95 μmol CO2 m-2 s-1), which demonstrates the ability of this species to develop under saline conditions (Figure 1).

Plants irrigated using solutions with lower NaCl concentrations in irrigation water (up to 100 mmol L-1) at the beginning of the evaluations had a progressive increase in photosynthesis as the light radiation pulse increased, with the highest values observed at PAR of 2000 μmol m-2 s-1 (Figure 1).

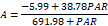

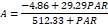

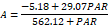

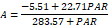

In plants irrigated with solutions more concentrated in NaCl (250 and 300 mmol L-1), significant gains were observed in photosynthesis up to the PAR of approximately 1400 μmol m-2 s-1; however, from this point on, the photosynthetic rates remained virtually unchanged (Figure 1). For each of these curves, the equations corresponding to each level of saline treatment were fitted separately and showed good performance in the modeling, with R2 values ranging from 0.72 to 0.99. These equations are described in Table 3.

Figure 1 CO2 assimilation curves as a function of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) intensity in Atriplex nummularia plants subjected to irrigation using water with different NaCl concentrations at 15 days after the beginning of saline treatment.

Table 3 Equations generated from the fit of the Michaelis-Menten model corresponding to the NaCl levels at 15 and 84 days of salt stress imposition

Plants subjected to prolonged stress (84 DAT) showed a pronounced reduction in net photosynthesis when compared to plants evaluated at 15 days (Table 3).

The increase of salinity in irrigation water caused more accentuated significant reductions (p≤0.05) in photosynthesis at 84 DAT than at 15 days. At the level of 50 mmol L-1, there was a reduction of 42.94%. However, much higher reductions (93.93%) were observed at the NaCl level of 250 mmol L-1.

Plants irrigated with water containing high concentrations of salts showed lower light saturation constant and the values ranged from 292.9 μmol m-2 s-1 in plants of the control treatment to 22.03 μmol m-2 s-1 in plants irrigated with water containing 250 mmol L-1 of NaCl (Table 2).

For this parameter, it was possible to observe reductions equivalent to 92.47 and 75.84% at NaCl levels of 250 and 300 mmol L-1, respectively. Regarding respiration in the dark, plants evaluated at 15 DAT experienced little or no reduction in this parameter. However, when plants were evaluated at 84 DAT, this parameter showed a large reduction already from the concentration of 50 mmol L-1 and, in general, the reductions were around 80%, demonstrating how debilitated the plants were (Tables 2).

With regard to the light compensation point, the decreases ranged from 14.63% at NaCl level 50 mmol L-1 to 95.93% at NaCl level of 300 mmol L-1.

At 84 DAT, plants were very stressed and virtually did not respond to the increase in light intensity. Except for plants in the control treatment, which exhibited an increase in net photosynthesis up to PAR of 1000 μmol m-2 s-1, all the others kept their photosynthesis rates practically unchanged from PAR of 800 μmol m-2 s-1, evidencing the presence of damage to the photosynthetic apparatus (Figure 2).

Figure 2 CO2 assimilation curves as a function of Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) intensity in Atriplex nummularia plants subjected to irrigation using water with different concentrations of NaCl at 84 days after the beginning of saline treatment.

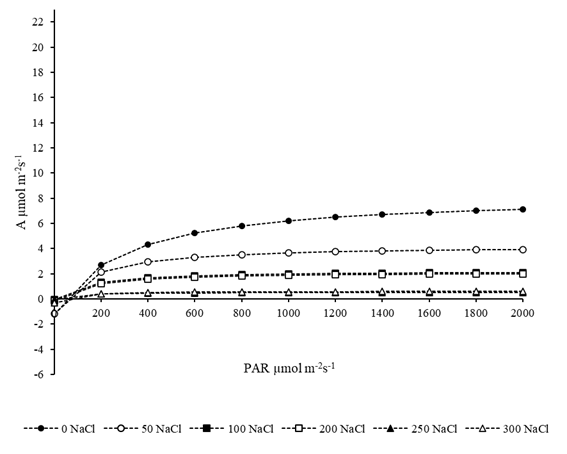

Stomatal conductance (Figure 3) was reduced as NaCl increased. The average values varied between 0.052 mol m-2s-1 and 0.01 mol m-2 s-1, corresponding to the control and exposed plants with concentrations of 0 and 300 mmol L-1 of NaCl, respectively

DISCUSSION

Although A. nummularia is a halophyte species with C4 metabolic pathway, this study demonstrated that when these plants are subjected to irrigations with concentrated saline solutions, they may exhibit a sharp reduction in photosynthetic rate.

This type of response to increasing salinity is probably the result of the activation of stomatal closure, which leads to reduction of CO2 diffusion to carboxylation sites (Dourado et al., 2022). Stomatal limitations, with subsequent reduction in photosynthesis and transpiration rates, can be considered as plant adaptation mechanisms to cope with the imposed salt stress (Benzarti et al., 2012).

The physiological logic that explains reductions in stomatal conductance in plants exposed to high salt concentrations in the saturation extract suggests that this mechanism may be the effect of the attempt to reduce water loss under “physiological drought” conditions imposed by salinity (Shabala, 2013). In general, these responses are mediated by the increase in the production of abscisic acid (ABA) (Ashraf and Harris, 2013) or by the reduction in the availability of K+ to maintain the turgor pressure of guard cells (Anschütz et al., 2014).

Under conditions of high salinity or prolonged salt stress, the photosynthetic rate may also be compromised due to the inhibition (synthesis or activity) of various photosynthesis-related enzymes, such as rubisco (Rivelli et al., 2002). In addition, ionic imbalances caused by excess Na+ and Cl- ions in cells can also lead to deficiency of ions such as potassium and to phytotoxicity, resulting in a lower photosynthetic efficiency (Abogadallah, 2010).

Under salinity, at 15 DAT, the maximum photosynthesis decreased to almost half of that in plants of the control treatment compared to those irrigated with solutions containing 300 mmol L-1 of NaCl. This could be visualized by observing the slope point of the curve of response to photosynthesis. Similar results, but with much lower values of photosynthesis, were observed at 84 DAT. Findings similar to those found in our study were observed by Geissler et al. (2015), who evaluated the effect of salinity on photosynthesis of A. nummularia plants by means of light curves.

Photosynthesis is considered an activity related to the Calvin cycle and indicates the regeneration capacity of rubisco under stress conditions. These results suggest that, although photosynthesis was inhibited by the reduction in CO2 supply due to stomatal closure, under both stress conditions, the potential of the reaction system in the dark was drastically reduced only when plants were exposed to long period of salt stress (Ueda et al., 2018).

In addition to stomatal closure, the reduction of photosynthesis in response to the saline treatment and prolonged exposure to salts can also be attributed to the reduction in chlorophyll concentration. On the other hand, the latter can reduce the capacity of light absorption by the leaf (Lu et al., 2003; Silva et al., 2013), which is evidenced by a lower light compensation point. This is also correlated with the decrease in photosynthetic efficiency (Φc) and is considered an important mechanism in relation to the defense of the plant against oxidative stress (Eisa et al., 2012).

In the present study, the effect of prolonged stress under salinity was evident, since the greatest reductions in photosynthesis were observed at the end of the experiment, compared to the increase in salt concentration in irrigation water, demonstrating that both photosynthetic efficiency and water use were more preserved at the beginning of the experiment. These results are in agreement with reports from other studies (Eisa et al., 2012, Hussin et al., 2013), and this is considered an important characteristic that allows halophytes to survive in saline environments during long periods of exposure to salts (Koyro, 2000).

The results demonstrate that excess sodium in irrigation water may have been responsible for the degradation of the thylakoid membrane reflected in the decrease in chlorophyll according with Geissler et al. (2015). Eisa et al. (2012), evaluating the effect of different NaCl concentrations (0, 100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 mmol L-1) in quinoa plants observed that the reduction in chlorophyll b concentration was accompanied by the increase in chlorophyll a and led to a reduction in photosynthesis efficiency in stressed plants.

In the evaluations at 15 DAT, plants did not show a reduction in photosynthesis efficiency; however, the prolonged exposure to irrigation observed at 84 DAT led to a decrease in photosynthesis efficiency even in plants of the control treatment, demonstrating that the decrease in this parameter may have been caused by other factors, such as the high temperatures of the protected environment or the size of the pot, which may have acted as a stress factor.

Eisa et al. (2012) also observed a decrease in photosynthetic efficiency (φ) as a function of the increase in NaCl concentration in irrigation water. The authors attribute this reduction to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which consequently leads to a reduction in the flow of electrons through the photosystem. As observed by Hussin et al. (2013), it was also noticed in the present study, at both evaluation times, that the light compensation point (LCP) decreased with the increase of NaCl in irrigation water. For these authors, this may be due to the greater stimulation of respiration, biosynthesis of compatible solutes and may be an adaptation mechanism of the plant to cope with stress.

In both evaluations, the highest values of net photosynthetic rate were observed at PAR corresponding to 2000 μmol m-2 s-1, and this result was independent of the NaCl concentration in the irrigation water. However, it was possible to observe that, at a given time, the plants no longer responded to the increase in light intensity. In plants evaluated at 15 days, the light intensity at which there was no significant increments in net photosynthesis corresponded to 1500, and this result could be observed in the most stressed plants (250 and 300 mmol NaCl L-1).

On the other hand, in the evaluations performed at 84 days, the light intensity at which the plants did not show gains in photosynthesis was much lower and corresponded to PAR of 800 μmol m-2 s-1, which demonstrates that in the case of salinity for the species evaluated, the time of exposure to salts, and consequently the ionic stress, is the main responsible for limiting the electron transport reaction, rubisco activity or the metabolism of triose phosphates.

CONCLUSIONS

Even in halophyte plants, such as A. nummularia, prolonged stress under high salt concentrations can cause damage to the photosystem both due to the occurrence of stomatal damage and due to the degradation of thylakoid membranes. The data obtained from the construction of photosynthesis x PAR curves demonstrated that the time of exposure to stress reduced the tolerance of this species to light stress.

In addition, the study provides data that support the choice of ideal PAR in evaluations of gas exchange in Atriplex nummularia, since our results clearly demonstrate under which condition of PAR the photosynthesis is maximum.

The knowledge of the photosynthetic performance of A. nummularia is relevant for application in programs of phytoremediation in salt-affected soils. Also, this research contributes effectively for providing data to help in the management of this species.