INTRODUCTION

In Portugal, as in other Mediterranean countries, where soil organic matter (SOM) in agroecosystems are quite below critical levels recommended by the UNCCD (United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification), the use of biowaste-based soil amendments seems an attractive option, because this practice enables valuable components to be reused (e.g., OM, N, P, K), avoiding, at the same time, the landfilling of organic wastes. However, there are associated threats, namely of soils contamination with potentially toxic trace elements (PTEs), organic contaminants, and pathogenic microorganisms, and their limit values have been established for sewage sludge (Decree-Law n.º 276/2009), and biowaste-based fertilizers (Decree-Law n.º 30/2022 and Portaria n.º 185/2022). Because of that, it is important to thoroughly analyse the risks of each specific material, considering its physicochemical characteristics, to compare the results with established limit values (Alvarenga et al., 2015), and its maturation/stability status (Alvarenga et al., 2016). However, despite the importance of their characterization, it is very important to evaluate the effects of the application of these biowaste-based amendments in field experiments, which can deliver more robust results, and the potential cumulative effects of their application to soil (Alvarenga et al., 2017). Generally, these studies emphasise the effects on soil physicochemical properties, more related with soil fertility aspects (e.g., pH, OM content, total and available nutrients’ concentrations, cation exchange capacity), or on the accumulation of pollutants (e.g., PTEs, persistent organic contaminants), both in soil and in the crop. These studies are very important, but they often disregard effects on other soil properties, like microbial and biochemical properties, that are good indicators of soil overall health (Bhaduri et al., 2022). For instance, dehydrogenase activity, as well as potential nitrification, are considered good indicators, representative of the active microbial population of a soil, while exoenzymes, such as hydrolases, can be used to assess the biological cycling of the elements, such as N, P, and C. All in one, they can be classified as metabolic soil bio-indicators, to evaluate ecosystem restoration and sustainability (Bhaduri et al., 2022).

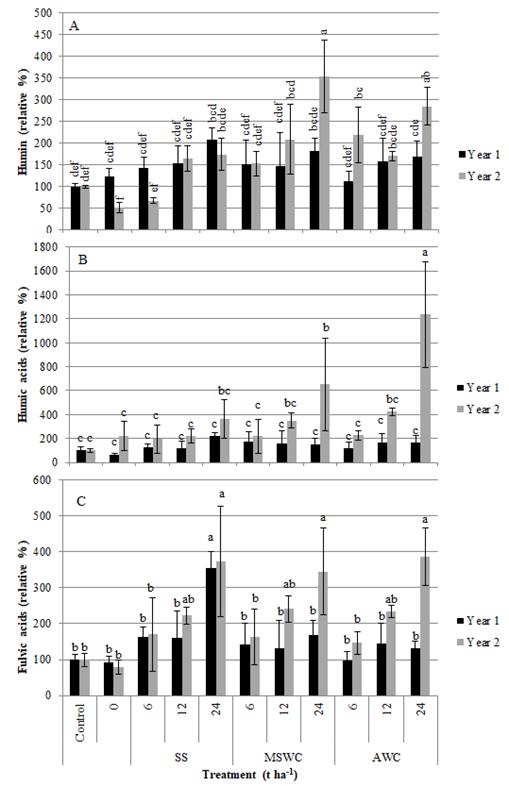

Considering the importance that SOM represents, as a property, to the agroecosystem, influencing soil fertility, nutrient cycling, water retention, and gases exchange (Weil & Brady, 2017), it is very important to evaluate the implications to the SOM when organic materials with different characteristics, namely regarding chemical composition (lignin, suberin), stability and maturity, are used as soil amendments (Alvarenga et al., 2016). The particulate fraction (free organic matter, FOM) is separated previously by density, and after is done via an alkaline extraction of the soil, obtaining the so-called humic substances (HS), composed by three fractions, operationally defined considering their pH-dependent solubility in aqueous solutions (humin, humic acids (HA) and fulvic acids (FA)) (Weil & Brady, 2017). Humin, insoluble in alkaline solutions, is formed by highly condensed, larger molecules, complexed with clays, resistant to decomposition, therefore considered the most stable fraction of SOM. On the other hand, HA (high molecular weight, up to 300,000 Da) and FA (lower molecular weight, 2,000-50,000 Da), both soluble in alkaline solutions, are composed by more reactive macro-molecules, HA more stable and less soluble than FA (Benites et al., 2003).

Several authors consider that the humic substances obtained in the alkaline extraction do not represent the nature of most of the organic material that exists in nature, and that SOM characterization should be performed by direct investigation of organic matter chemistry in situ, while it is still associated with the mineral phase (Weil & Brady, 2017; Kleber & Lehmann, 2019). Nevertheless, when the edaphoclimatic conditions are similar, variations on these soil alkali-extracted fractions are still used by many authors to evaluate the influence of different soil management options on SOM properties (Kou et al., 2022).

Taking all these into consideration, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects on SOM fractions, extracted by alkali, and on soil biochemical properties (nitrification potential, dehydrogenase activity, and soil exoenzymes activity), of the use of three different biowaste-based amendments (sewage sludge and compost produced from urban or agricultural wastes).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Field experiment

The field experiment was established in a Vertisoil (WRB, 2022), in Beja (Portugal; 38°01′42.08″N, 7°52′11.70″W), sown with Lolium multiflorum L. The soil amendments used were: (1) dewatered sewage sludge (SS; 6, 12 and 24 t dry matter (dm) ha-1), (2) mixed municipal solid waste compost (MSWC), and (3) agricultural wastes compost (AWC), applied in rates calculated to deliver the same amount of organic matter (OM) per unit area of soil, in two consecutive years (2014-2015). Briefly, the SS was obtained in a small municipal wastewater treatment plant (serving ~6000 inhabitants), after activated-sludge treatment, with high aeration rate, nitrification-denitrification, and mechanical dewatering by centrifugation (~15% dry matter content). The MSWC was obtained from unsorted municipal solid waste, mechanically segregated, and biologically treated, in a composting plant serving ~113000 inhabitants. The AWC was produced from the wastes of the cleaning of olive groves, and of harvesting and processing of olives to produce olive oil, and from manure generated in a biological farm (61% sheep manure, 21% olive mill waste, 10% olive leaves, and 8% meat flour) (Alvarenga et al., 2015). Two control treatments were considered: one ploughed and sown, as the others, but without organic amendment application (zero (0) ton ha-1 application rate), and a control with intact soil (Control). The thorough description of the experimental set-up and of the results obtained for the physicochemical properties of soil, and for the effects on plant and on soil PTEs’ accumulation, were already reported and discussed (Alvarenga et al., 2017).

Soil organic matter fractionation

SOM was separated in operationally defined fractions (humin, HA and FA), extracted following the simplified methodology described by Benites et al. (2003). A soil sample with, approximately 30 mg total organic carbon, was extracted with NaOH 0.1 M, shaken for 24 h (200 rpm) at 25 °C in the absence of light, and after centrifuged at 5,000 g for 30 min. This extraction procedure was repeated twice, and allowed the separation of the humin fraction, which is retained, insoluble, in the precipitate, from the extract with soluble HA and FA fractions. The extract was then acidified to pH = 1.0, with H2SO4 20% (w/w), to allow their separation: HA, with higher molecular weight, which precipitates in acid solutions, from FA, with lower molecular weight, which remains in the supernatant. The separation of both fractions was performed by filtration, through a 0.45 µm filter, under vacuum. The HA precipitate, retained in the filter, was further solubilized, by washing it with NaOH 0.1 M. Organic carbon in the three fractions (humin, in the precipitate, and HA and FA, in each extract), was quantified by the Walkley-Black method: titration with Mohr's salt (ammonium iron (II) sulfate, (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2(H2O)6), with ferroin indicator, after oxidation of each fraction with K2Cr2O7 (0.1667 M for humin and 0.0125 M for HA and FA extracts), with concentrated H2SO4, at 150 ºC for 30 min. All samples were measured in triplicate.

Soil enzymatic activities

At the end of the experiment, soils were collected and maintained at field moisture content before analysis. Enzymatic activities analytical protocols were thoroughly described by Alvarenga et al. (2009), all using 2-mm sieved samples, and with the activities expressed on oven-dried weight basis (105 ºC, 48 h). Dehydrogenase activity (Tabatabai, 1994) was measured as soon as possible after soil sampling (< 48 h), while for β-glucosidase (Alef & Nannipieri, 1995a), acid phosphatase (Alef et al., 1995), cellulase (Hope & Burns, 1987), and protease (Alef & Nannipieri, 1995b), soil samples were kept refrigerated at 4 ºC, and let to equilibrate for 1 h, at room temperature, before analysis. All analytical measurements were carried out in triplicate.

Potential nitrification

Potential nitrification was measured according to Berg & Rosswall (1985), with some modifications. Field-moist soil samples were incubated for 5 h at 25°C using ammonium sulphate 1 mM as substrate (2 g soil: 8 mL solution), in the presence of sodium chlorate has a nitrite oxidation inhibiter. Nitrite released during incubation was extracted with potassium chloride and determined colorimetrically at 540 nm.

Data analysis and statistical treatment of data

To avoid biased results related with soil sampling in different years, all results were expressed as a percentage, relative to the result obtained for the same variable in the control plot (Control) in that same year. Results were analysed using descriptive statistics (mean, and standard deviation), and were subjected to a two-way ANOVA to evaluate statistical differences between the results, and the interaction of the tested independent variables (treatment × year). Whenever significant differences were found (p ≤ 0.05), a post hoc Tukey Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test was used to further elucidate differences among means (p ≤ 0.05). All statistical analyses were performed with the STATISTICA 7.0 (Software™ Inc., PA, USA, 2004).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Soil organic matter fractionation

SOM alkali extracted fractions (humin, FA and HA), increased with the treatment doses, and, as a general trend, from the first to the second year of the study, evidencing the benefit of amending the soil with exogenous sources of organic matter.

Humin (Figure 1A), is the most persistent and stable fraction of SOM, which plays a very important role in C sequestration in soil. Humin was dominant over the other fractions (between 80-91% of the total C in humin, for all treatments), as was expected in an agricultural soil (and in a Vertisoil). For HA (Figure 1B), more stable than FA, their content in the soil increased more markedly following the composts application, with statistically significant differences after the AWC higher application dose (p<0.05), reached in the second year of the study. The effects of SS application were more evident for the FA increase (Figure 1C), especially in the first year of their application. FA correspond to more active and soluble compounds (Benites et al., 2003; Kou et al., 2022), and it is expected that SS, an organic material less stabilized and with a higher rate of mineralization compared with both composts (Alvarenga et al., 2016), would have a more marked effect on the FA fraction of SOM. In fact, in the second year of the study, the higher application dose of SS led to a slight decrease in humin, and to an increase in FA.

Figure 1 Effects of the treatments on soil organic matter fractions in the two years of the study: (A) humin, (B) humic acids and (C) fulvic acids (mean ± standard deviation, n=4). Results are reported as percentage, relative to the result obtained in the Control. Columns marked with the same letter are not significantly different (Tukey test, p>0.05).

Effects on soil biochemical indicators

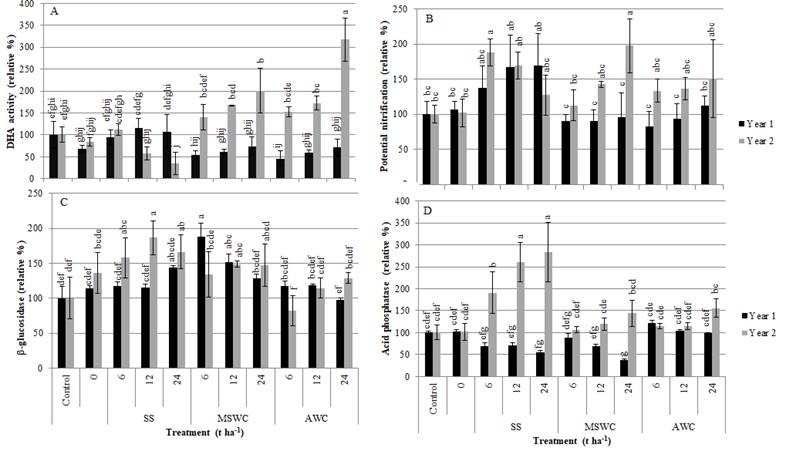

Except for SS application in some cases or for some doses, overall, the biochemical indicators were positively affected by organic amendments application (Figure 2), with considerable increases in their values, relatively to the control or to the seeded non-amended plot.

Figure 2 Effects of the treatments on soil biochemical properties in the two years of the study: (A) dehydrogenase activity (DHA), (B) potential nitrification, (C) β-glucosidase activity, and (B) acid-phosphatase activity (mean ± standard deviation, n=4). Results are reported as percentage, relative to the result obtained in the Control. Columns marked with the same letter are not significantly different (Tukey test, p>0.05).

Regarding dehydrogenase activity (DHA), an overall indicator of soil microbial activity (Figure 2A), while in the first year of the study the beneficial effect of SS application was higher than that observed for both composts application, the second year of application of the same material evidenced an opposite tendency, with a decrease in DHA activities with increasing SS application rates. An opposite tendency was observed following composts application, with more stabilized OM, leading to an increase of DHA activity, with the increase in the application rates of both composts. As for potential nitrification (Figure 2B), the response of this biochemical indicator followed the same trend as the DHA, but with values, for SS, considerable higher than the controls in the second year of the study (p<0.05).

As for these biochemical parameters, associated with microbial activity, there is an apparent benefit of applying stable high-quality organic matter, at least in the medium term, with a negative response to the consecutive application of non-stabilized organic matter, still in an active mineralization phase, as SS.

Generally, soil enzymatic activities (β-glucosidase (Figure 2C), acid-phosphatase (Figure 2D), cellulase and protease), increased with the treatment doses, and markedly from the first to the second year of the study. In fact, following the first year of application of the amendments, the differences for the enzymatic activities of β-glucosidase and acid-phosphatase, between the amended and non-amended soil, were not significant (p>0.05), but their activities increased markedly in the second year of application, especially for SS application, with statistically significant higher activities than with the compost application, MSWC and AWC (p<0.05).

As for, cellulase and protease, their activities were below the quantification limit of the technique in the first year but increased their activities to quantifiable values following the second year of amendment applications (data not shown). Their activities were, however, still low and, because of that, with high standard deviation between replicates. Nevertheless, it was possible to observe that SS was the amendment which promoted the highest increase in their activities, possible because of the higher rate of mineralization of SS, compared to the stabilized composts, already pointed by Alvarenga et al. (2017), when discussing the effects of the treatments on the soil physicochemical parameters.

Despite the rather higher response of the hydrolases to the SS application, when compared to the compost application, the application of 24 t ha-1 of SS, in the second year of application, also induced a decrease in the enzymatic activity of β-glucosidase (Figure 2C) and cellulase (data not shown), both enzymes from the C-cycle.

CONCLUSIONS

These results emphasize the importance of applying biowaste-based amendments to boost microbial and biochemical properties of soil, which increased by their application doses (especially with the 12 and 24 t ha-1 application doses), and from the first to the second year of application. However, for some properties, mainly those related with microbial activity, like DHA activity and potential nitrification, the positive response decreased in the second year of application of less stabilized organic materials, like SS, while the same properties continued to increase with composts application.