Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Arquivos de Medicina

versão On-line ISSN 2183-2447

Arq Med vol.28 no.6 Porto dez. 2014

CARTA AO EDITOR

A tale of two countries -safe motherhood in Portugal and Nigeria

Musa Abubakar Kana1,2

1Epiunit – Institute of Public Health, University of Porto (ISPUP), Porto, Portugal

2Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Kaduna State University, Kaduna, Nigeria

Key-words: Safe Motherhood, Maternal Health, Portugal, Nigeria

Dear Editor,

The attainment of the global goal of safe motherhood is a major challenge to health systems.1-3 Nearly every 2 minutes, somewhere in the world, a woman dies because of complications of pregnancy and childbirth.1 A fact that confers maternal mortality as a widely acknowledged general indicator of the overall health of a population, of the status of women in society, and of the functioning of the health system.4 High maternal mortality ratios (MMR) are thus markers of wider problems of health status, gender inequalities, and health services in a country.4 Therefore, an international comparison of maternal health requires taking into account the differences in demographic and socio-economic determinants of health.

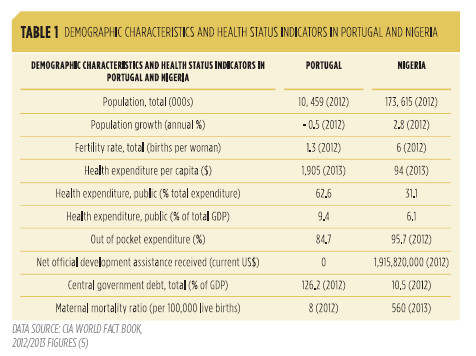

Portugal has a small population and the economy is recovering from a period of recession, while Nigeria has a large population and a rapidly developing economy.5 Maternal mortality in Portugal was decreased from 40 to less than 10 deaths per 100,000 live births between 1978 and 1986.6 On the other hand, Nigeria has over the period of 23 years recorded a decline of 52% in maternal deaths from 1200 per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 560 per 100,000 live births in 2013.7,8 The rate of reduction of maternal mortality in the two countries is incongruent due to a host of factors that include the differences in their initial scale of the burden, health system and intervention approaches.

An international comparison based on the concept of amenable to health care avoidable mortality (that is, mortality sensitive to health care system initiatives) provides a rating of the improvement in health status attributable to the health system.9 The strength of a health system offers an important and sustainable mechanism to influence key population level indicators of health, including maternal mortality ratio.10 Therefore, coordinating actions across different parts of the health system, initiatives to improve maternal health can increase coverage and reduce barriers to the use of various services.11 Through a holistic understanding of a health systems building blocks,12 systems thinking identifies where the system succeeds, where it breaks down, and what kinds of integrated approaches will strengthen the overall system and thus assist countries to improve maternal health.13

The comparison of safe motherhood in Portugal and Nigeria illuminates the concerns that underscore the distinctive challenges each faces. Maternal death is a rare event in Portugal, but the consistent increase in the average age at pregnancy may exacerbate the main causes of death, raising concerns for the future and prompting the need for emergency facilities nearby maternities.6 Even though maternal mortality is declining in Nigeria, the country still contributes 14% of global maternal deaths.14 The high maternity rate has been related to inadequate use of maternal healthcare services.15,16 Sustainable improvement of access to maternal health services will require commitment by stakeholders and consistent implementation of health policies; specifically an integrated approach to strengthen the health system should be the strategy of choice.17

Finally, it seems a future without maternal mortality is far from being attained. But for now, the goal of every human society should be ensuring safe motherhood that gives all mothers an opportunity to survive pregnancy and childbirth.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to express his gratitude to Professor H. Barros, teachers and colleagues at the Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto (ISPUP) for their contribution towards his understanding of health systems, which inspired this work.

References

1. Lawson GW, Keirse MJ. Reflections on the maternal mortality millennium goal. Birth. 2013;40(2):96-102. [ Links ]

2. Ohaja M. Safe motherhood initiative: what is next? The practising midwife. 2014;17(6):16-8. [ Links ]

3. Hogan MC, Foreman KJ, Naghavi M, Ahn SY, Wang M, Makela SM, et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980-2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 2010;375(9726):1609-23. [ Links ]

4. World Health Organization. Reproductive health indicators : guidelines for their generation, interpretation and analysis for global monitoring. Geneva, Swittzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [ Links ]

5. Central Intelligence Agency. The World Fact Book: CIA; 2013. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/. Accessed 28th November 2014 [ Links ]

6. Gomes MC, Ventura MT, Nunes RS. How many maternal deaths are there in Portugal? The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine. 2012;25(10):1975-9. [ Links ]

7. Federal Office of Statistics [Nigeria] and IRD/Macro International Inc: Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 1990. 1992. Lagos, Nigeria and Columbia, Maryland, USA: Federal Office of Statistics and IRD/Macro International Inc.,

8. National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. 2014. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria and Rockville, Maryland, USA:NPC and ICF International. [ Links ]

9. Nolte E, McKee M. Measuring the health of nations: analysis of mortality amenable to health care. BMJ. 2003;327(7424):1129. [ Links ]

10. Muldoon KA, Galway LP, Nakajima M, Kanters S, Hogg RS, Bendavid E, et al. Health system determinants of infant, child and maternal mortality: A cross-sectional study of UN member countries. Globalization and health. 2011;7:42. [ Links ]

11. Huntington D, Banzon E, Recidoro ZD. A systems approach to improving maternal health in the Philippines. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90(2):104-10. [ Links ]

12. World Health Organization. Everybodys business – strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHOs framework for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [ Links ]

13. Atun R, de Jongh T, Secci F, Ohiri K, Adeyi O. Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. Health policy and planning. 2010;25(2):104-11. [ Links ]

14. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA,The World Bank: Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [ Links ]

15. Doctor HV. Intergenerational differences in antenatal care and supervised deliveries in Nigeria. Health & place. 2011;17(2):480-9. [ Links ]

16. Ononokpono DN, Odimegwu CO. Determinants of Maternal Health Care Utilization in Nigeria: a multilevel approach. The Pan African medical journal. 2014;17 Suppl 1:2. [ Links ]

17. Spicer N, Bhattacharya D, Dimka R, Fanta F, Mangham-Jefferies L, Schellenberg J, et al. Scaling-up is a craft not a science: Catalysing scale-up of health innovations in Ethiopia, India and Nigeria. Social science & medicine (1982). 2014;121c:30-8. [ Links ]

Musa Abubakar Kana

Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto (ISPUP)

Rua das Taipas, 135 - 4050-600 Porto, Portugal. E-mail: up201308483@med.up.pt