1. Introduction

Stuttering involves more than just observable behaviors, such as repetitions, prolongations, and blocks (Bloodstein et al., 2021). It should be viewed as a multifactorial issue involving environmental, genetic, and constitutional factors (Ambrose & Yairi, 1999; Conture, 2001; Smith & Weber, 2017; Rocha et al., 2019a; Rocha et al., 2019b) that can lead to activity limitations and participation restrictions in a person’s life (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019; Yaruss & Quesal, 2004; 2006). Stuttering is likely to affect education, health, personal relationships, social life, and occupation (e.g. Beilby et al., 2012; Boey, 2012; Craig et al., 2009; Rocha et al., 2020; Yaruss & Quesal, 2016). Because of the broad-based nature of stuttering, it is important to take into account the perceptions and experiences of those who stutter when planning evaluations and treatment (Yaruss & Quesal, 2006).

As documented in prior studies, stuttering can significantly impact children (Rocha et al., 2020; Yaruss & Quesal, 2016). A previous study used the European Portuguese translation of the Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering (OASES-S-PT), (Rocha et al., 2020) to examine the experiences of Portuguese school-age children who stutter. Analyses revealed a mild-to-moderate overall impact, including low overall self-awareness of stuttering and negative emotional reactions associated with stuttering. Findings also revealed difficulty in communicating in specific situations, such as speaking in large groups (Rocha et al., 2020). Based on these findings, it is clear that speech-language therapists can use the OASES-S-PT to measure the impact of stuttering based on the self-perception of children who stutter. It is also important to consider the perspectives of those who interact with children who stutter on a daily basis, because these perceptions can influence children’s experiences. For many children who stutter, the school-age years can be difficult due to the need to engage in speaking activities associated with their education. These activities might include raising their hands to speak in class, asking and answering questions, and talking with teachers (Cooke & Millard, 2018; Daniels et al., 2012). Also, adults who stutter have reflected on the difficulties they experienced at school. In the study of Klompas and Ross (2004) about life experiences of people who stutter, participants recall major difficulties in school, especially when participating in speech-related activities such as oral presentations. Some participants also report that stuttering affected their interactions with their teachers. Some participants reported a lack of understanding of stuttering by their teachers, leading to situations that increased their communication difficulty (e.g., not receiving extra time to speak). Other participants highlighted more positive reactions from the teachers (e.g., being placed in smaller groups), which helped them deal with their stuttering more easily.

Considering that children spend a lot of time in schools and that teachers are the primary adults with whom children interact in that setting, it is meaningful to explore whether teachers can provide relevant information about children’s behaviors and affective reactions to stuttering (Boey et al., 2009; Bothe & Richardson, 2011; Langevin et al., 2010; Pros et al., 2017; Seixas et al., 2014). Several studies have shown that it is important for teachers to cooperate in the assessment and treatment of children with various conditions, such as learning disabilities and neurodevelopmental problems (Al-Awad & Sonuga-Barke, 2002; Firmin et al., 2000; Harlen, 2005; Schatz et al., 2001; Ulloa et al., 2009). Analyses of teachers’ responses in these studies generally show that the information provided by teachers is valid; however, further information is needed regarding teachers’ perceptions about stuttering. In particular, it is necessary to determine whether they provide accurate information about the condition to their students. If teachers are to serve as allies in the therapy process, they must have appropriate knowledge about stuttering (Blood et al., 2010; Cooke & Millard, 2018; Hayhow et al., 2002). To date, there are no standard instruments that can be explicitly applied to teachers to explore their perspectives regarding the impact that stuttering may have on their students. Therefore, this study aimed to develop such an instrument and use it to explore teachers’ perceptions about the impact of stuttering on their students who stutter.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

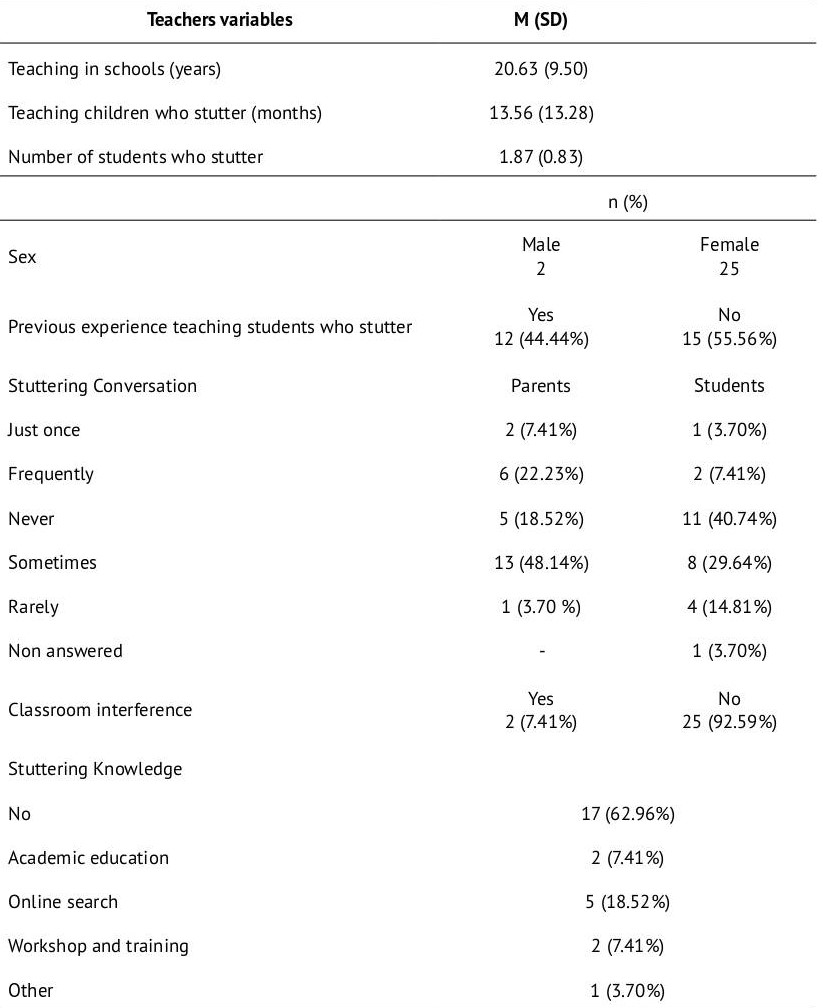

Participants were 27 teachers and their students who stutter (n=27; mean age=9.0 mos., SD=1.8 mos.) recruited from different cities in Portugal. Tables 1 and 2 show demographic characteristics of teachers and their students who stutter. Specifically, Table 1 includes general information about teachers’ level of experience and information about the teachers’ prior experiences with stuttering and with students who stutter.

Of the teacher participants, 25 of the 27 (92.6%) were women. Overall, 55.6% of the participants reported not having prior experience teaching a student who stuttered in their class. Of the teachers who had already taught children who stutter, 40.7% reported never talking about stuttering with their students. However, 48.1% indicated that they had discussed stuttering with their students’ parents. A lack of knowledge about stuttering was reported by 63.0% of the teachers. Of those who claimed to have some knowledge about the condition, 18.5% reported that they acquired this knowledge through an online search.

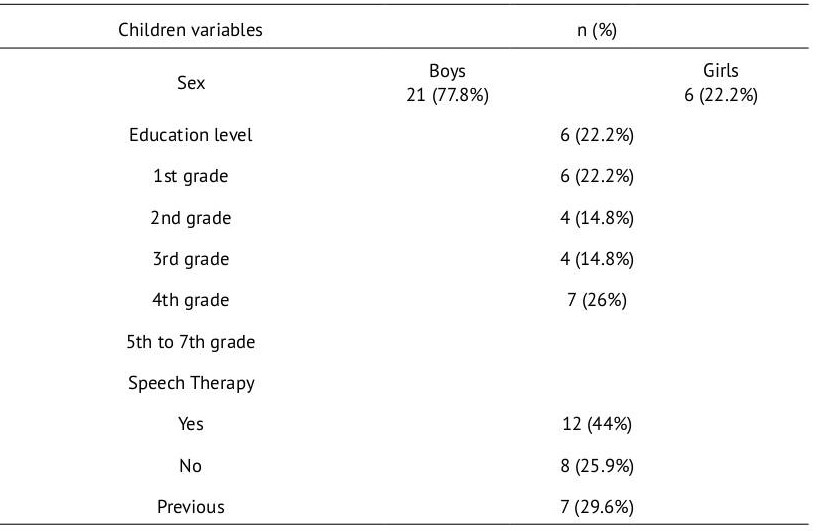

Table 2 shows the children’s age, sex, education level, and prior therapy history demographic characteristics. The sex ratio of children who stutter was 3.5 boys to each girl (21 male and 6 female). The sample includes only children without any neurological impairment (other than stuttering), psychiatric disturbance, history of head injury, learning disorder, or seizure disorder, as confirmed through parent reports. Participants were recruited from speech-language therapist caseloads and through referrals by teachers and other professionals throughout Portugal. The sample was taken from a broader study (n=50) about the impact of stuttering on children’s lives (Rocha et al., 2020).

2.2 Materials

The Stuttering Severity Instrument - fourth edition SSI-4 (Riley, 2009) was used to confirm the children’s diagnosis of stuttering. The SSI-4 is a reliable and valid norm-referenced stuttering assessment widely used for both clinical and research purposes to measure stuttering severity and to assesses the frequency, duration, physical concomitant behaviors, and naturalness of speech through pictures and reading. Because the original reading texts are in English, this study used a Portuguese-language story, “A história do rato Artur” (Guimarães, 2007). This story has been used in several prior studies in Portuguese (Guimarães & Abberton, 2005; Silvestre, 2009) because it yields a high test-retest consistency and is phonetically balanced. Therefore, it has been interpreted as closely reflecting spontaneous discourse (Moon et al., 2012). Some of the younger children (7-8 years old) found it hard to read the story (n = 8), so only the standard SSI-4 pictures were used for them.

Descriptive data about teachers and their students were collected through a checklist created for this study (see Tables 1 and 2). Information about children’s stuttering history and socio-demographic background, including sex, therapy history, education level, and family history of stuttering, was provided by their parents via another checklist.

Results from the European Portuguese version of the Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering (OASES-S-PT) (Rocha et al., 2020; originally developed by Yaruss & Quesal, 2016) were used to compare the children’s perceptions of stuttering with the teachers’ perceptions. An adaptation of the OASES specifically for teachers (OASES-S-PT-T) was developed for the present study. This adaptation followed the same procedures as the Portuguese versions of the OASES-S for school-age (OASES-S-PT) (Rocha et al., 2020) and parents (OASES-S-P) (Rocha et al., 2019c).

The original OASES-S, the European Portuguese version of the OASES (OASES-S-PT), and the European Portuguese version of the OASES for Teachers (OASES-S-PT-T) are all divided into 4 sections: Section I (General Information) contains 15 items about the speakers’ perceived fluency, speech naturalness, knowledge about stuttering, and overall feelings about stuttering; Section II (Your Reactions to Stuttering) contains 20 items aimed at examining speakers’ affective, behavioral, and cognitive reactions to stuttering; Section III (Communication in Daily Situations) includes 15 items aimed at assessing how hard speakers find it to communicate in generic scenarios, at school, socially, and at home; and Section IV (Quality of Life) contains 10 items aimed at assessing how much stuttering interferes with speakers’ satisfaction with their ability to communicate, their ability to actively participate in life, and their overall sense of well-being. In preparing the adaptations, slight changes were made to verb conjugations and pronouns, so the questions in the OASES-S-PT-T could be directed to teachers. For example, the first question: “How often can you speak fluently (without stuttering)?” was modified into: “how often is your student able to speak fluently (without stuttering)?”

3. Procedures

This study received full approval from the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Health Sciences of Universidade Católica Portuguesa (register number 34/2017). Parents provided informed consent for themselves and their children. Consent also included permission for the researcher to record the child and confirmed the participants’ right to withdraw from the study at any time. The teachers agreed to participate in the study with the school board's permission.

Assessment of the children and collection of parent-provided information were carried out simultaneously in different rooms. Sociodemographic checklists were filled out by parents (about 5 minutes) while, in a separate quiet room, the researcher completed the SSI-4 and the OASES-S-PT with the child (about 15 minutes). The OASES-S-PT-T and the teachers’ checklist were provided to the teachers via the parents. The forms were placed in a sealed envelope, together with a cover letter explaining the study's aims. Once completed by the teachers, the documents were returned to parents, then forwarded to the researchers.

A total of 50 questionnaires were initially distributed; responses from 27 teachers were returned and included in the study. All testing was conducted between December 2017 and June 2018.

4. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted with SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences -Version 24 for Windows). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to determine the normality of impact scores for Portuguese teachers and children. In comparing scores between children and teachers, paired-sample t-tests were used for variables with normal distributions, and Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests were used for variables with non-normal distributions. We chose to use two different tests to more effectively detect statistically significant differences, given that parametric tests are more appropriate for normally distributed data. In contrast, non-parametric tests are more robust to violations of normality. Correlations between the children’s impact scores and the teachers’ impact scores were evaluated using Spearman’s rho, a statistical procedure suitable for non-normal populations and small samples (Marôco, 2010).

5. Results

5.1. OASES-S-PT and OASES-S-PT-T Results

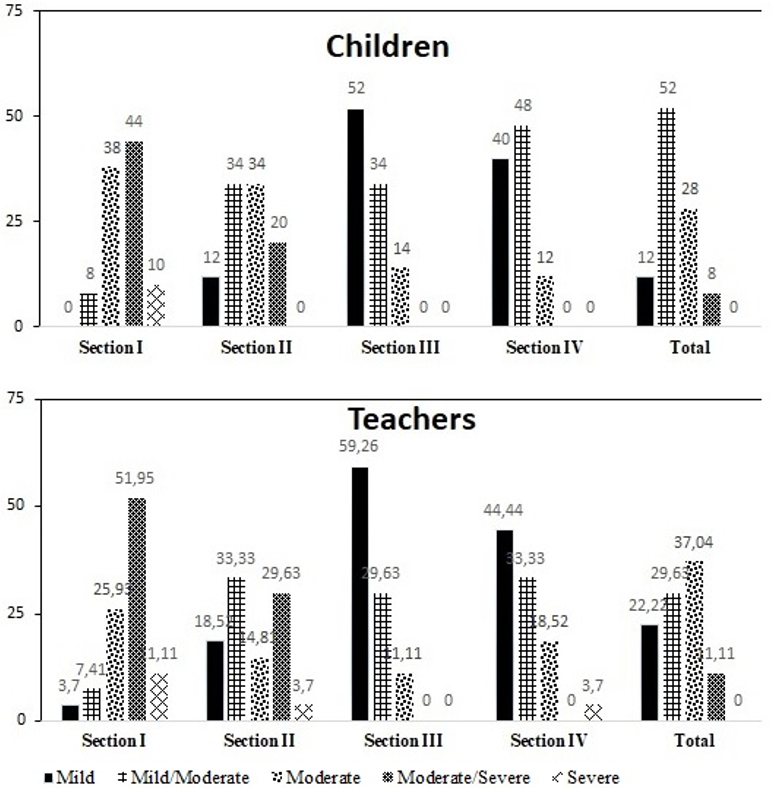

The distribution of scores for the four sections and overall impact ratings of the OASES-S for teachers (OASES-S-PT-T) and students (OASES-S-PT) are represented in Figure 1.

Analyses revealed that 37.04% of teachers reported a moderate overall impact of stuttering for their students; roughly half of the children (48.15%) reported the same impact range for themselves. A mild-to-moderate overall was reported by 29.63% of the teachers and children, and 22.22% of the teachers and children reported a mild impact. A moderate-to-severe impact was reported by 11.11% of teachers. None of the teachers rated the impact of stuttering as severe and none of the children rated the impact of stuttering as moderate-to-severe or severe.

Examining the individual sections of the OASES-S-PT and the OASES-S-PT-T, both teachers and children revealed a negative perception in Section I (General Information: 51.85% for teachers and 40.74% for students). For both groups, the impact of stuttering in section I was rated as moderate-to-severe.

In Section II (Their Reactions to Stuttering), 29.63% of teachers reported a moderate-to-severe impact. The same percentage of children (29.63%) rated themselves as experiencing a mild and a moderate impact, and 25.03% rated themselves as experiencing a mild-to-moderate impact of stuttering.

Less impact was revealed in Section III (Communication in Daily Situations) and Section IV (Quality of Life), with more than half of the teachers (59.26%) and roughly half of the children (51.85%), respectively, rating a mild impact and a mild-to-moderate impact on daily communication; both groups indicated a mild impact on quality of life.

Table 3 shows that the non-response rate for certain items was high, suggesting that teachers might not have insights into some aspects of their students’ experiences. Section I (General Information) had the highest rate of non-answers. Almost half of the teachers (44.4%) failed to respond to the question related to students’ use of techniques or strategies learned in speech therapy. In Section II (Their Reactions to Stuttering), the least-answered questions addressed physical tension that the students might experience in their speech, 18.8% of teachers did not answer these questions. In Section III (Communication in Daily Situations), the highest rate of non-answers was found in questions related to the difficulties that children experience when communicating at home. In Section IV (Quality of Life), 33.3% did not answer the question of how much students’ lives were affected by needing to go to speech therapy.

Table 3: Mean (M), standard deviations (SD) and p-values for the impact scores of children who stutter (n=27) and their teachers (n=27).

| Impact Scores | Children who stutter M (SD) | Teachers M (SD) | t/z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 2.789 (.627) | 3.033 (.688) | t= -1.531 | .138 |

| II | 2.106 (.835) | 2.318 (.924) | t= -.972 | .340 |

| III | 1.495 (.430) | 1.428 (.560) | z= -.745 | .456 |

| IV | 1.540 (.604) | 1.704 (.714) | z= -1.090 | .276 |

| Total score | 2.022 (.542) | 2.116 (.635) | t= -.664 | .513 |

5.2 Comparison and correlation of OASES-S scores of teachers and their students who stutter

Overall, both teachers (2.02 ± 0.54) and children (2.12 ± 0.64) perceived a moderate overall adverse impact of stuttering; Table 4 shows the mean impact rating scores comparison between teachers and their students. There were no statistically significant between-group differences (p > .05) in the impact score means.

Table 4: Correlations (Spearman’s rho) among student’s impact scores and teacher’s impact scores.

| Impact Scores | Correlation coefficient (p value) |

|---|---|

| I | .200 (.317) |

| II | .215 (.281) |

| III | .319 (.105) |

| IV | .214 (.283) |

| Total score | .265 (.182) |

As shown in Table 5, there was no significant correlation between students’ impact scores and teachers’ impact scores (p > .05).

6. Discussion

This study asked teachers about how stuttering impacts their students’ lives and compared their responses to responses previously collected from children. Most teachers and students who stutter rated the degree of impact due to stuttering as moderate. According to the teachers, the students themselves, and the results from Section I, most students have little knowledge about stuttering. This finding is consistent with previous studies (Rocha et al, 2020). Teachers’ responses were likely influenced by their overall lack of knowledge about stuttering (Carroll, 2010; Li & Arnold, 2015; Silva et al., 2016). The large number of specific items skipped by teachers reinforces this notion. Many teachers indicated that they had never talked about stuttering with their students. These results suggest that teachers’ general lack of awareness about stuttering could cause them to misunderstand typical reactions from their students, given that children’s feelings and attitudes toward stuttering are not always obvious. This appears to be mainly for teachers who are not accustomed to dealing with stuttering and those who work with large groups of students, where individualized attention is not always possible.

The overall results from this study indicate that teachers perceive the impact of stuttering on the lives of their students to be moderately negative. This impact can be seen in negative emotional reactions and attitudes toward speaking and stuttering. Common examples of these reactions include embarrassment, frustration, and anxiety. Such findings support the idea that treatment for school-age children should include multiple goals based on each child’s individual needs, and that these goals should not only focus on enhancing fluency but also address other goals, such as acceptance of stuttering, minimizing avoidance, and reducing negative emotions associated with stuttering (Cooke & Millard, 2018; Murphy et al., 2007; Reardon-Reeves & Yaruss, 2013; Yaruss et al., 2012). Reducing children’s negative emotions can also support children’s use of speaking strategies to further reduce the impact of stuttering (Howard, 2013; Murphy et al., 2007; Reardon-Reeves & Yaruss, 2013; Yaruss et al., 2012).

Both teachers and children identified an adverse impact of stuttering in the school setting. These results agree with previous literature that highlights the burden of living with stuttering, either for the children themselves or for those around them. This includes research on attitudes toward stuttering (Boey, 2012; Guttormsen et al., 2015), the impact of stuttering on children (Beilby et al., 2012; Yaruss & Quesal, 2016), and parent’s perspectives about the impact of stuttering (Rocha et al, 2019c; Cooke & Millard, 2018). These results confirm the importance of gathering information from multiple people in the child's life during the assessment process. In particular, teachers can provide unique insights into children’s experiences in the classroom, and this can lead to better cooperation between clinicians and teachers in the treatment of children who stutter (Blood et al., 2010; Cooke & Millard, 2018; Daniels et al., 2012; Miller, 1999; Murphy et al., 2007; Reardon-Reeves & Yaruss, 2013). Findings also highlight the need for treatment to address children’s communication difficulties in specific scenarios, such as speaking with peers and large groups.

Teachers’ perceptions of the impact of stuttering on children’s lives may have been influenced by their perceptions of stuttering, as well as by their views about the future for their students who stutter (Dorsey & Guenther, 2000; Turnbull, 2006). Teachers’ negative stereotypes and perceptions regarding people who stutter have previously been identified (Dorsey & Guenther, 2000; Turnbull, 2006). This might have contributed to teachers' perceptions of the negative impact on their students’ lives.

Although teachers were able to provide insights about children’s experiences in the school setting, they were, not surprisingly, unable to provide information about children’s communication difficulties at home or in other settings outside of the school. This is made clear by the number of skipped items related to the issues mentioned above in the teachers’ responses on the OASES-S-PT. It may also reflect the teachers’ lack of understanding about stuttering and a lack of information sharing between speech therapists and teachers. The majority of teachers did not know how to respond to treatment-related issues. They also stated that they had no knowledge about stuttering and never talked about stuttering with their students. This is in agreement with studies that report a lack of teachers’ knowledge about what they can do to help their students deal with stuttering (Li & Arnold, 2015; Silva et al., 2016). Together, these findings emphasize the importance of incorporating teachers into the therapy process. The results highlight how fundamental it is to implement awareness-raising, teacher-targeted efforts. Brochures and videos may be used to provide general information, and regular meetings involving parents, teachers, and therapists could further the dissemination of accurate information about stuttering (Carroll, 2010).

No significant differences were found between teachers’ and their students’ answers to the adapted OASES instruments (OASES-S-PT for students and OASES-S-PT-T for teachers). This could mean that the groups' responses were, in general, very similar. At the same time, there was no significant correlation between the impact scores of students and teachers. Previous studies about learning disabilities and neurodevelopmental problems have shown positive correlations between children’s and teachers’ responses (Al-Awad & Sonuga-Barke, 2002; Firmin et al., 2000; Harlen, 2005; Schatz et al., 2001; Ulloa et al., 2009). This suggests that further study on this relationship is needed. The low correlation in this study may be related to the small number of participants and some missing items in the teachers’ responses. Regardless, findings highlight the need to improve partnership among teachers and speech therapists and increase teachers' knowledge about stuttering (Carroll, 2010; Li & Arnold, 2015).

7. Final Considerations

This study focused specifically on teachers’ perceptions; additional research will be needed to better understand whether there are differences between children's perceptions and the perceptions of other professionals (such as speech-language pathologists), as well as siblings and other family members. Findings should be interpreted with caution due to the relatively small sample and the non-response rate for some items. Importantly, cultural factors may also influence teachers’ perceptions, so replicating this study with a more significant sample, both in Portugal and in other countries, will be needed so that therapeutic programs can be customized according to each country’s cultural identity. It is also important to consider that this is the first time that the OASES-S-PT-T measure has been used with teachers. Given the low response rate for some items, it may be that some of the questions were harder for teachers to interpret. Further expansion and replication of this research will be needed to understand the role of these factors in the participants’ responses.

The present findings highlight the need to develop a closer and more effective relationship between therapists and teachers, especially because the perceptions about stuttering may impact how teachers cope with students who stutter. Although teachers in this study did perceive that their students were experiencing a moderate negative impact due to stuttering, there were several areas in which the teachers did not have clear insights. This suggests that speech-language pathologists can do more to clarify teachers about common experiences for children who stutter, particularly the nature of speech therapy for children who stutter (e.g., Reardon-Reeves & Yaruss, 2015).

To conclude, this study highlights the importance of ensuring that teachers have an adequate understanding of the experiences of children who stutter; outreach campaigns in schools could help to demystify stuttering for teachers. Improving teachers’ knowledge of stuttering will help to create a more supportive school atmosphere for children who stutter.