1. Introduction

In Spain, according to the current law of education (LOMLOE, 2020), the students in need of special educational support are those who need and receive different educational attention from the regular one. This group includes students with special educational needs, whose need for educational support is associated with an impairment or serious disorder. According to data from the Spanish Ministry of Education (2022), during the last academic year of which data are available (2020-2021), 227.979 students with special educational needs were enrolled in the Spanish non-university educational system. 82.3% of these students were integrated into mainstream schools. The percentage varies depending on the type of impairment. The highest integration percentage corresponds to students with severe personality or behavior disorders (98.4%), followed by students with hearing impairment (95.2%), students with vision impairment (95%), students with motor impairment (87.9%), students with general developmental disorders (83.3%), students with intellectual impairment (75.3%) and students with multiple disabilities (35.3%).

The success of inclusive education depends to a large extent on teachers’ attitudes and specific training to address diversity within the teaching and learning process, as confirmed by numerous recent studies (Ginja & Chen, 2023; Rodríguez-Gómez et al., 2017; Sharma & Jacobs, 2016). In their recent study, Lindner et al. (2023) set out to address whether teachers support the inclusion of all students. Their systematic review findings revealed that, in the context of inclusive education, regular primary school teachers generally do not prioritize the inclusion of all students. The interest in gaining knowledge on pre-service and in-service teachers’ attitudes toward disability or inclusion has contributed to the large development of research in this field, which has led to many studies (Gónzalez-Gil et al., 2017; Hernández-Amorós et al., 2018; Kielblock & Woodcock, 2023; Novo-Corti et al., 2014; Saloviita, 2020). Among other variables, attitudes toward inclusion have been examined based on gender, specific training and previous contact with people with disability as differentiating variables. The findings of previous research suggested that the participants with the broadest training on disability (Nowicki, 2006) and who had had prior contact with people with disability (Maras & Brown, 1996; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006) showed the best attitudes toward disability and/or inclusion. Nevertheless, in the case of gender, there is controversy, since some studies revealed that women illustrated better attitudes toward disability (Litvack et al., 2011; Solís García & Borja González, 2021), while others found that men did (Nabuzoka & Ronning, 1997; Solís García & Arroyo Resino, 2022) and others concluded that gender was not a variable that should be considered (Tamm & Prellwitz, 2001).

Within this context, the aim of this research was to assess attitudes toward inclusive education of pre-school and primary education (3-12 years) pre-service and in-service teachers. Besides, it was aimed to differentiate those attitudes based on variables such as gender, specific training, previous contact with people with disability, age, or teaching experience. The aims of the present study can be specified as follows: i) to examine the differences among participants based on gender, specific training and previous contact with people with disability; ii) to compare the results between pre-service and in-service teachers; and iii) to establish relationships between attitudes toward inclusion and age, as well as between these attitudes and teaching experience in the case of in-service teachers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

The sample was composed of 409 participants: 320 students of the Bachelor (BSc) in Teacher Education (232 women; 88 men) aged between 18 and 47 (M = 21.33; SD = 3.44) and 89 in-service teachers (61 women; 28 men) aged between 25 and 62 (M = 44.61; SD = 10.81). Among all the participants, 75.55% report prior contact with people with disabilities, and 50.12% indicate specific training in the inclusion of students with disabilities.

2.2 Instrument

The Spanish version of Saloviita’s Teachers’ Attitudes towards Inclusive Education Scale (TAIS) was used (Saloviita, 2015), so-called TAIS-SP. That version was adapted to the Spanish context by Fernández-Bustos et al. (2022) and recently utilized by Cañadas et al. (2023). The scale was composed of nine items with 5-point Likert-type answers, from "totally disagree" to "totally agree". Since it is a unidimensional questionnaire, the total sum of the scores of every item (after inverting the scores for the five items with negative meaning: 1, 3, 5, 6, 9) was established as a variable for attitude assessment.

Three scale items contained clearly regulatory statements that referred to inclusion as a value, this is, they expressed the convenience of inclusion (items 2, 4 and 7) (e.g., "The education of children with emotional and behavioral problems should be arranged in mainstream classrooms with the provision of adequate support"). Likewise, two items mentioned the right of children to specific treatment (items 3 and 9) (e.g., "It is the right of a child with special educational needs to get into a special education classroom"). One item that evaluated teachers’ workload in inclusive education was selected (item 5) ("Teachers’ workload should not be augmented by compelling them to accept children with special educational needs in their classrooms"). The three remaining items (1, 6 and 10) evaluated the learning outcomes of children in different contexts (e.g., "The learning of children with special educational needs can be effectively supported in mainstream classrooms as well"). These items were statements related to the convenience of inclusion.

2.3 Procedure

For sample selection, one class was randomly chosen from every year (first to fourth) of the BSc in Teacher Education of two Faculties of Education from the same university in central Spain. Participants filled in an informed consent form, through which they were advised of the research aims and which emphasized voluntary participation, confidentiality, and the lack of influence of participation on the course evaluation. The volunteers, all of legal age, completed the questionnaire before the lesson. Physical separation guaranteed the privacy of their responses, and sufficient time was allowed for appropriate reading, comprehension and answer selection (10 minutes). In the case of teachers, mainstream schools of Albacete (Spain) from the authors’ network were selected. Teachers were recruited after providing identical previous information and guaranteeing the same conditions for student participation.

2.4 Data analysis

Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene tests were conducted to assess normality and homoscedasticity, respectively, before deciding whether to apply parametric or non-parametric tests for data analysis. Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to determine whether there were differences in the attitudes toward inclusive education (dependent variable) among the groups under study or based on the independent variables (gender, in-service teacher-BSc student, training on inclusion, contact with people with disability). Rosenthal r value was calculated to determine the effect sizes. Besides, Kruskal-Wallis test for independent samples was performed to determine whether there were differences in attitudes based on the different types of contact with disability and the types of impairment. Complementarily, correlation analysis (Spearman’s Rho) was performed to examine the relationships of inclusive attitudes with age and teaching experience. All the tests were conducted using the statistical package SPSS 25.0.

3. Results

Since the corresponding tests revealed that the variable sum of scores of TAIS-SP items was not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were conducted to determine whether there were differences in attitudes toward inclusive education between in-service teachers and BSc students, as well as differences based on gender, training on inclusion or contact with people with disability.

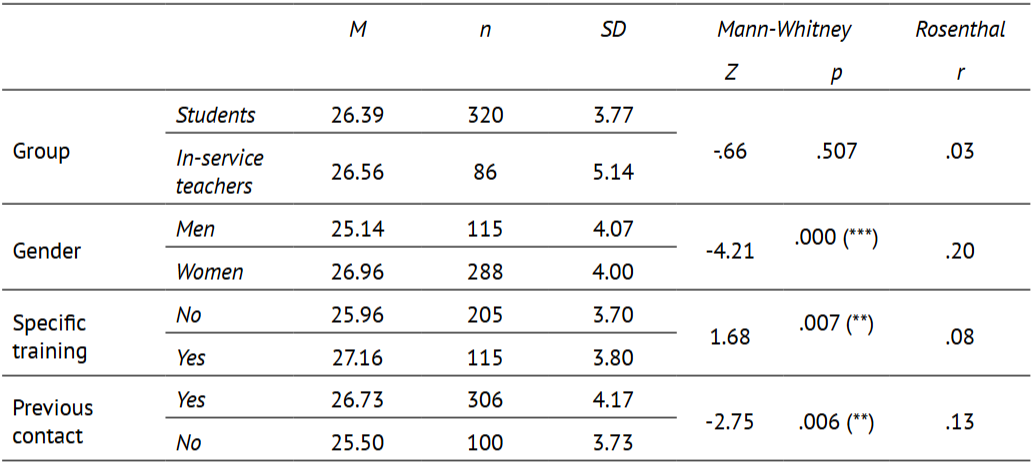

As shown in Table 1, no differences in attitudes were detected between in-service teachers and BSc students (Z = -.66; p > .05). Nevertheless, the differences were significant for the rest of the independent variables. Women (Z = -4.21; p < .001), students with training on inclusion (Z = 1.68; p = .007) and participants who had ever been in contact with people with disability (Z = -2.75; p = .006) showed more positive attitudes toward inclusion. According to the criteria established by Cohen (1988), the effect size was small, being in all cases in the range r ≤ .20.

Kruskal-Wallis test for independent samples was applied with the purpose of determining whether attitudes toward inclusion were different among participants who had reported previous contact with people with disability depending on the type of impairment (visual, physical, intellectual) or the type of contact (friend, colleague/classmate, relative, volunteerism). Nonetheless, no differences were found based on the type of impairment (p = .134) or the type of contact (p = .131).

Table 1: TAIS-SP values by group, gender, specific training and previous contact.

Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

A correlation analysis was also conducted to confirm whether teaching experience in teachers or age in students and teachers were related to inclusive attitudes. Age and attitudes were negatively correlated in the case of teachers (r = -.214; p < .05), while positively correlated in the case of students (r = .161; p < .05).

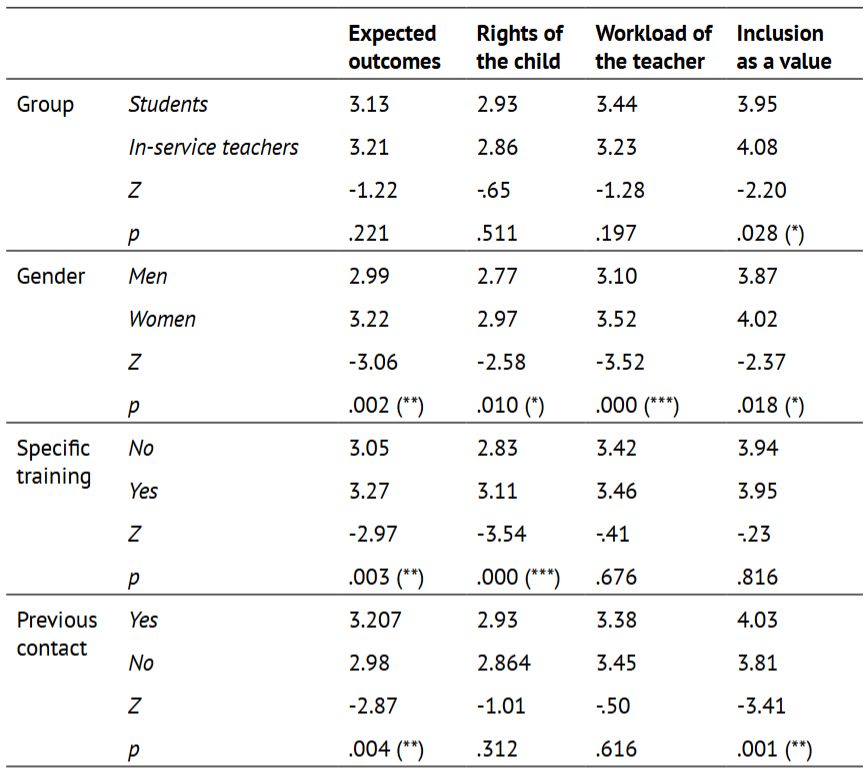

Table 2 contains the mean scores of the four categories proposed by Saloviita (2015) and included in TAIS (Expected outcomes, Rights of the child, Workload of the teacher, and Inclusion as a value). In this case, in-service teachers achieved higher scores than students in the category of Inclusion as a value (Z = 2.20; p = .028). Besides, women scored higher than men in all four categories, the differences being most relevant in the Workload of the teacher (Z = 3.52; p < .001) and Expected outcomes (Z = 3.06; p = .002). Important differences were also found between students who had and had not received training on inclusion, but only in Expected outcomes (Z = 2.97; p = .003) and Rights of the child (Z = 3.54; p < .001). Likewise, participants who had reported contact with people with disability scored higher only in the categories of Expected outcomes (Z = 2.87; p = .004) and Inclusion as a value (Z = 3.41; p = .001).

4. Discussion

The main aim of the present study was to evaluate pre-service and in-service teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion in Spain. The differences based on the participants’ gender, specific training and previous contact were examined. In the case of gender, women presented significantly more positive attitudes than men toward inclusion. Contradictory results can be found in the literature in this regard. Thus, while some studies are in line with the present research (Çiçek-Gümus & Öncel, 2021; Ellins & Porter, 2005), some have confirmed that men presented more positive attitudes toward inclusion or disability (Nabuzoka & Ronning, 1997), making other authors conclude that gender cannot be considered as a determining variable in attitudes toward inclusion (Woodcock, 2013). van Steen and Wilson (2020) identified moderate gender-related effects in their meta-analysis. The findings from this study indicate that women may exhibit more favorable attitudes toward inclusion compared to men. When dividing participants by their previous contact with people with disability, those who reported previous contact showed significantly more positive attitudes toward inclusion, in keeping with previous studies (Vignes et al., 2009). This idea was confirmed by a recent meta-analysis conducted by Dignath et al. (2022), where it was observed that educators possessing specialized training in special education displayed more favorable inclinations toward inclusion. One of the most determining factors in negative attitudes toward disability is the lack of knowledge. Therefore, sharing life aspects with people with disability (colleagues, friends, or relatives) predisposes individuals to present more positive attitudes (Nowicki, 2006).

Another independent variable under study was previous training on inclusion. Significant differences were detected between 1st-year BSc students, who had not completed specific courses yet, and the rest of the participants (2nd-, 3rd- and 4th-year students). These results are in keeping with the scientific literature, which, as it occurred with previous contact, states that the wider the specific training (BSc students in Teacher Education receive more training on this topic as they progress within the degree), the more positive the attitudes toward disability. For example, Vaz et al. (2015) showed that age, gender, and specific training were the most relevant variables to explain teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion. In the case of training, teachers who had received specific training on inclusion or disability suggested more positive attitudes toward inclusion. Furthermore, the research conducted by Scanlon et al. (2022) demonstrated a significant association between inclusion-related training and the emergence of favorable attitudes toward inclusion among educators in Bulgarian Kindergarten contexts.

To show a more complete picture, the data obtained were analyzed using the four categories proposed by Saloviita (2015). The analysis based on gender showed that women presented more positive attitudes towars inclusion than men in all four categories, with especially high values in the category Workload of the teacher. These findings follow the idea that women present more positive attitudes toward disability or the inclusion of people with disability, as confirmed by previous studies (Litvack et al., 2011). Participants who had received specific training (2nd-, 3rd- and 4th-year BSc students) presented higher values in the categories of Rights of the child and Expected outcomes. Participants who reported previous contact with people with disability showed significantly higher values than those without previous contact in the categories Inclusion as a value and Expected outcomes. These results agree with the idea that individuals with broader knowledge and training on disability (Nowicki, 2006) or with previous contact (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006) show more positive attitudes toward disability and inclusion. Álvarez and Buenestado (2015) also found previous contact to be a predictor of a positive attitude toward inclusion. These data can be used to design future programs with the purpose of changing attitudes toward inclusion.

About the second aim, pre-service and in-service teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion were compared, and no significant differences were observed between groups. By contrast, differences were detected when the analysis was conducted, dividing them into the categories proposed by Saloviita (2015). In-service teachers showed higher values than pre-service teachers in the category of Inclusion as a value and, therefore, presented more positive attitudes toward inclusion. Once more, it seems like in-service teachers’ greater previous contact, because of their years of experience, is an essential aspect of determining more positive attitudes, in agreement with previous studies (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). However, in the research conducted by Ismailos et al. (2022), findings indicated that pre-service teachers exhibited a preference for a student-centered classroom environment that emphasizes student autonomy and differentiated instruction. Additionally, they displayed higher levels of self-assurance in their capacity to effectively engage students through accommodation strategies. Due to this controversy, this topic needs a more in-depth investigation.

In response to the third aim, potential relationships between attitudes toward inclusion and years of experience and age in in-service teachers and between attitudes and age in students were examined. The findings revealed a negative correlation between age and attitudes in teachers but positive in the case of BSc students. The results for teachers are in keeping with previous studies (Garzón Castro et al., 2016) that showed that younger teachers and, therefore, those with shorter experience, showed more positive attitudes toward inclusion and were more willing to apply inclusive methodologies compared to older teachers. As regards students, it seems like the older they were, the more positive their attitudes were toward inclusion. This fact seems to be associated with the previously explained idea about specific training, since the older the student, the broader their training and, therefore, the more positive their attitudes toward inclusion, in line with the previous study by Álvarez and Buenestado (2015). This would support the idea of Vaz et al. (2015), who suggested specific training as one of the predictors of teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion. Finally, Solís García and Real Castelao (2023) found that teachers with more than ten years of teaching experience exhibited favorable attitudes toward inclusion in a sample of Spanish special education teachers.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this brief report suggest that aspects such as specific training and previous contact with people with disabilities have an influence on teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain). These key findings raise some interesting questions about how to improve the quality of inclusion for students with disabilities in mainstream schools. We recommend that future research try to evaluate the effect, in terms of attitudes, of including contact and specific training in the initial teacher’s education programs and in the programs of training of in-service teachers. These questions could offer a starting point for further research. We also propose the incorporation of self-efficacy pertaining to inclusion to accomplish a more comprehensive understanding of the concept of educational inclusion among Spanish teachers.

Nevertheless, limitations such as the number of participants and the specific localization of the participants within the same geographical area avoid the possibility of generalizing these findings, so more research in diverse contexts is necessary to complete the picture about teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion in Spain. Finally, given that education falls within the jurisdiction of autonomous communities, it would be of interest to compare various regions across Spain to investigate the impact of specific legislation and teacher education programs.