Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Portuguese Journal of Nephrology & Hypertension

versão impressa ISSN 0872-0169

Port J Nephrol Hypert vol.31 no.3 Lisboa set. 2017

CASE REPORT

Amyloidosis related to HIV – An unusual cause of nephrotic syndrome in HIV patients

Sofia Coelho1, Ana Fernandes1, Elsa Soares1, Patrícia Valério1, Ana Farinha1, Ana Natário1, Joana Sá2

1 Nephrology department, Centro Hospitalar de Setúbal

2 Infectious diseases department, Centro Hospitalar de Setúbal

ABSTRACT

Human immunodeficiency virus infection is a multisystemic disease which causes kidney disease in a variable proportion of infected patients. AA amyloidosis, in turn, is an unusual complication related to HIV infection and also an infrequent cause of kidney disease; in this setting AA amyloidosis usually results from chronic skin infections related to intravenous use of recreational drugs. We report the case of a 43-year-old woman, native of the Ivory Coast, with active HIV 1 infection diagnosed 11 years ago, currently in the Centers for Disease Control and Preventions stage C3, out of antiretroviral therapy for non-adherence and with persistent positive viral load, admitted to the nephrology department for nephrotic syndrome. The patient denied any other relevant clinical history, including chronic or recurrent inflammatory or infectious disease or use or abuse of recreational drugs.

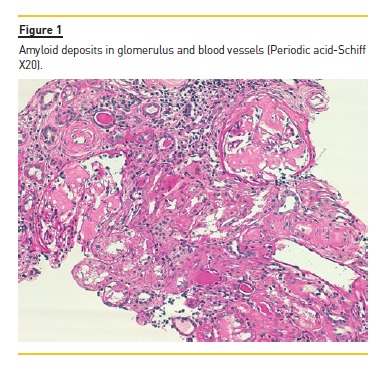

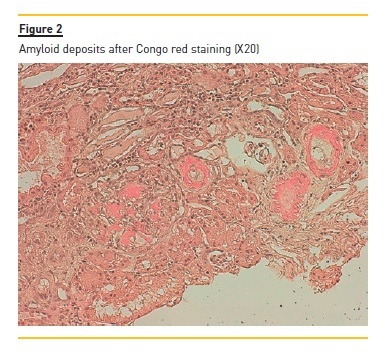

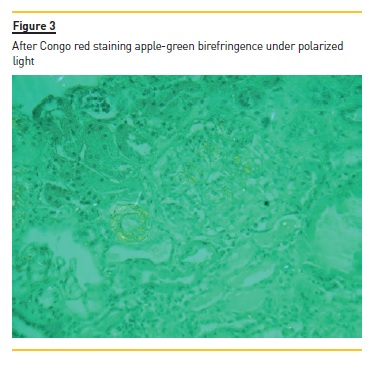

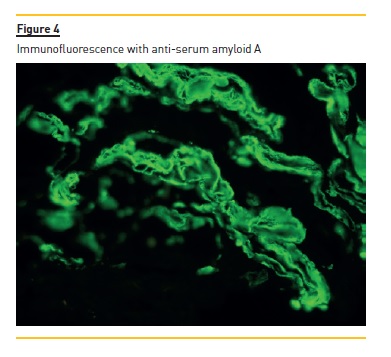

Urine sediment and renal function were both normal as was renal ultrasound. Other opportunistic infections were excluded. The renal biopsy revealed deposition of amorphous substance, Congo red positive, in the vascular walls and a positive immunofluorescence for serum amyloid A, confirming the diagnosis of renal amyloidosis.

The patient was started on antiretroviral and symptomatic therapy, with clinical improvement. The clinical diagnosis of renal amyloidosis secondary to HIV can be challenging, as it requires the exclusion of other possible aetiologies, but should be considered in the differential diagnosis of renal disease in HIV patients. This case illustrates the importance of the renal biopsy in such cases in which the diagnosis can be improperly set up if based only on clinical data.

Key-Words: AA amyloidosis; antiretroviral therapy; human immunodeficiency virus infection; nephrotic syndrome; renal biopsy.

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV)/ acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a multisystemic disease which has become a global pandemic1.

With prolonged survival and aging of the HIVinfected population in the era of antiretroviral therapy, a growing number of diseases affecting different organ systems in the general population are becoming manifest in these patients2, as is the case of kidney disease related to HIV infection1.

Patients with HIV are at risk of both acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD), secondary to nephrotoxic medication, HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) and other glomerulopathies2. In addition, HIVpositive patients may be at increased risk of progressive kidney disease related to hepatitis B or C virus co-infection, and comorbid or treatment-related diabetes and hypertension2. Renal disease in HIV-infected patients was first described by Rao et al3 in 1984, as a focal and segmental glomerulonephritis subsequently termed HIVAN, and although this is usually the most common histologic renal lesion in these patients, renal biopsy series have found a broad spectrum of HIV-related kidney disease4, such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, minimal change disease, membranous glomerulopathy, immunocomplex glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy and AA amyloidosis, which together make up as much as one-third of cases5. Our understanding of the epidemiology and clinical course of these other HIV-related renal diseases remains limited5.

AA amyloidosis is an uncommon cause of renal disease in HIV patients6,7. It is a disorder of the protein metabolism that can complicate a number of chronic inflammatory and infectious diseases8 characterized by ongoing or recurring inflammation that results in the production of serum amyloid A, an acute phase reactant which can form amyloid deposits9. Usually present as a nephrotic syndrome, with progressive loss of renal function5, AA amyloidosis can be associated with a heterogeneous group of disorders, with autoimmune diseases the most common causes of AA amyloidosis in developed countries, whereas untreated chronic infections are the predominant cause in countries with limited medical resources10. The aetiologic mechanisms of AA amyloidosis in the context of HIV infectionis not well established11; AA amyloidosis in this setting usually occurs as a result of chronic infections, particularly skin infections related to intravenous use of recreational drugs7. Renal disease related to intravenous drug use (IVDU) has been reported since the 1970s, in that period mostly in the context of heroin-associated nephropathy10. Despite the yet unclear nature of the relationship between AA amyloidosis and HIV, it has been observed that serum amyloid A protein (SAA) levels are high in patients with chronic infections12, such as noncontrolled HIV infection, which would, in theory, predispose the patient to the development of AA amyloidosis.

The increased frequency of AA amyloidosis in HIV-infected patients has been hypothesized as being related to the progressively higher life expectancy of these patients and the observed increased secretion of amyloid13.

CASE REPORT

We report the case of a 43-year-old melanodermic female patient, native of the Ivory Coast, resident in Portugal for several years, who was referred to the Department of Nephrology after a 10-day history of swelling of the lower extremities and hypertension.

The patient had active HIV-1 infection diagnosed 11 years ago and was in CDC (centers for disease control and prevention) C3 stage. The antiretroviral therapy had been precociously interrupted for non-adherence and the patient maintained positive viral load over the time. Six months before the current episode, she was started on emtricitabin, tenofovir, lopinavir and ritonavir, again with poor compliance. The last measurement of viral load result was 600 copies/ml (15 days before) and the CD4+ T cells were 243/μl (2 months before).

Furthermore, there was a history of cholelithiasis, uterine leiomyoma and depressive disorder for which she had been recently medicated with amitriptyline 25mg daily. The patient denied any further relevant medical history, in particularly hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, chronic or recurrent inflammatory or infectious disease, such as mycobacterial infection, pneumocystis, toxoplasmosis, CMV infection or other related to HIV infection, or neoplasms. She also denied the use of intravenous drugs and no familial history of AA amyloidosis was known.

Upon admission, clinical examination showed pronounced lower limb oedema and a blood pressure of 160/80 mmHg. No history of fever, haematuria or other urine abnormalities was disclosed, and no respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms were present.

The laboratory studies revealed microcytic/hypochromic anaemia (9.9g/dl) associated with iron deficiency, hypoalbuminaemia (2.8g/dl), hypercholesterolaemia (268mg/dl) and a nephrotic proteinuria of 13g/24h, with bland urine sediment, consistent with the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome. The leukogram and platelets were normal as were serum creatinine urea and ionogram. Blood tests were also negative for autoimmunity diseases, monoclonal gammopathies, HCV, HBV, syphilis infection or other opportunistic infections. The renal ultrasound showed normal-sized kidneys, a mild renal parenchyma hyper-echogenicity. In order to clarify the aetiology of the nephrotic syndrome, the patient underwent renal biopsy, which showed deposition of amorphous substance in all the 7 glomerulus presented in the biopsy and in the vascular walls (Figure 1), with a positive Congo red staining (Figures 1 and 2), tubular atrophy (35%) and interstitial fibrosis (35%). The immunofluorescence was positive for amyloid A and negative for kappa and lambda chains (Figure 4). The screening of other organs for amyloid deposition detected a mild hepatosplenomegaly and was otherwise negative, including the transthoracic echocardiography.

At the time of diagnosis, the patient was started on diuretic and anti-proteinuric therapy, and a significant clinical improvement followed. The antiretroviral therapy was changed with tenofovir eviction, in order to prevent further renal lesion. The patient evolved with regression of proteinuria (~0.5g/24h) and maintains a normal renal function at the 6 month follow up, under antiretroviral therapy and low dose angiotensin II receptor antagonist.

DISCUSSION

As the prevalence and survival of HIV is increasing, the spectrum of renal disorders in HIV patients is also changing and all varieties of glomerular and tubulointerstitial disorders can be found on histology1. AA amyloidosis is an uncommon cause of renal disease and nephrotic syndrome in HIV-positive patients (6, 7) and usually occurs as a complication of chronic inflammatory or infectious disease. In the past, it was reported in intravenous or subcutaneous drug abusers, some of whom were HIV-positive6.

Two studies from Europe reported an increased prevalence of renal AA amyloidosis in patients with IVDU14,15. However, only a few cases have been recorded in the literature of HIV-infected patients with AA amyloidosis who have no history of drug consumption.

In 1992 Cozzi et al11 described AA amyloidosis in association with HIV infection in a 38-year-old patient with HIV infection and haemophilia, with an history of multiple transfusions and a right hip inflammatory process related to an infected prosthesis (without evidence of osteomyelitis). In this case, the underlying disease was uncertain and the authors suggested that AA amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome in patients with AIDS. Jatem et al7 reported the case of a patient with an HIV infection who was a chronic user of intravenous drugs and developed acute renal failure and nephrotic syndrome due to secondary AA amyloidosis. They did not identify any condition that could explain the presence of the secondary AA amyloidosis, but given the long evolution of the HIV infection and drug abuse, it would be impossible to discern the cause of the AA amyloidosis. Navarro et al13 describes a case of non-oliguric acute renal failure with nephrotic syndrome in a Caucasian patient with both HIV and HCV infections, in whom the biopsy showed AA amyloidosis. This was a case of AA amyloidosis not preceded by recurrent infections, in which recovery of the renal function and resolution of the nephrotic syndrome were objectively demonstrated after antiretroviral therapy, similarly to our case.

The clinical case we hereby describe is an HIV-positive patient who presented with nephrotic syndrome but without renal failure. Given the medical history, the differential diagnosis included HIVAN, non-HIVAN focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis and other glomerulopathies such as AA amyloidosis, which a renal biopsy subsequently confirmed. However, no history of drug abuse, chronic infection or other disorder usually associated with reactive AA amyloidosis was found, leading to the conclusion that the AA amyloidosis was secondary to the long-term uncontrolled HIV infection itself. Observational studies have suggested that antiretroviral medications and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have beneficial effects, slowing the progression of renal disease in HIVAN patients. Still, little is known about the effect of these therapies on other renal lesions, namely on AA amyloidosis5. In the present case, the treatment has been effective, at least in the short term.

In HIV patients with renal disease, the CD4 cell count at presentation seems to be associated with progression to ESRD, namely in HIVAN. The question remains whether the same occurs in AA amyloidosis secondary to HIV, but it seems likely that the immunologic status may be related to a more aggressive renal disease and a faster progression to end stages5. Szczech et al16 observed that an absolute CD4 cell count of ≤200 cells/mL, a detectable HIV RNA level, increasing systolic blood pressure, increasing creatinine and decreasing albumin are predictors of progression of renal disease among women with HIV-related renal diseases and proteinuria, meaning that this markers of viral replication and immune status may have an impact on the mechanism of the progression of nephropathy. In our patient, some of these predictors were present and she also had a heavy proteinuria, which probably justify a tighter follow-up and monitoring of renal function.

In conclusion, HIV-related renal dysfunction is an important entity with quite variable aetiology1 and AA amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis, particularly in patients with nephrotic syndrome11.

The clinical diagnosis of AA amyloidosis secondary to HIV infection itself as the cause for renal disease can be challenging, as it requires the exclusion of other more frequent causes, such as HIVAN. Therefore, histology is crucial because the clinical diagnosis, based on degree of proteinuria, CD4 count or viral load, may not predict the pathological diagnosis in HIV-positive patients6,17. More studies are needed to reach a better understanding of the prognosis and more appropriated treatment.

References

1. Vali PS, Ismal K, Gowrishankar S, Sahay M. Renal disease in human immunodeficiency virus Not just HIV-associated nephropathy. Indian J Nephrol 2012; 22(2): 98-102. [ Links ]

2. Overview of kidney disease in HIV-positive patients. Available at https://www.uptodate.com. Accessed January 16, 2016. [ Links ]

3. Rao TK, Filippone EJ, Nicastri AD et al. Associated focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 1984; 310:669-673. [ Links ]

4. Wyatt CM, Morgello S, Katz-Malamed R et al. The spectrum of kidney disease in patients with AIDS in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Kidney Int 2009; 75(4): 428-434. [ Links ]

5. Szczech LA. Renal diseases associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection: epidemiology, clinical course, and management. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33: 115-119. [ Links ]

6. Chan-Tack KM, Ahuja N, Weinman EJ et al. Acute renal failure and nephrotic range proteinuria due to amyloidosis in an HIV-infected patient. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332(6): 364-367. [ Links ]

7. Jatem E, Loureiro J, Curran A. Secondary amyloidosis in a HIV patient. Nefrologia 2011; 31(6): 747-764. [ Links ]

8. Causes and diagnosis of secondary (AA) amyloidosis and relation to rheumatic diseases. Available at https://www.uptodate.com. Accessed January 16, 2017. [ Links ]

9. Overview of amyloidosis. Available at https://www.uptodate.com. Accessed January 16, 2017. [ Links ]

10. Jung O, Haack HS, Buettner M et al. Renal AA-amyloidosis in intravenous drug users – a role for HIV-infection? BMC Nephrology 2012; 13: 151. [ Links ]

11. Cozzi PJ, Abu-Jawdeh GM, Green RM, Green D. Amyloidosis in association with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 1992; 14: 189-191. [ Links ]

12. Husebekk A, Permin H, Husby G. Serum amyloid protein A (SAA): an indicator of inflammation in AIDS and AIDS-related complex (ARC). Scand J Infect Dis 1986; 18: 389-394. [ Links ]

13. Navarro JM, Díaz CC, Marrón B, Barat A, Praga M, Riñón C. Amiloidosis AA en paciente infectado por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana: comunicación de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Rev Clin Esp 2003; 203(1): 50-53. [ Links ]

14. Connolly JO, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ, Davenport A, Hawkins PN, Woolfson RG. Renal amyloidosis in intravenous drug users. QJM 2006; 99(11):737-742. [ Links ]

15. Manner I, Sagedal S, Røger M, Os I. Renal amyloidosis in intravenous heroin addicts with nephrotic syndrome and renal failure. Clin Nephrol 2009; 72(3):224-228. [ Links ]

16. Szczech LA, Gange SJ, Van der Horst C et al. Predictors of proteinuria and renal failure among women with HIV infection. Kidney Int 2002; 61: 195-202. [ Links ]

17. Mery JP, Delahousse M, Nochy D. Amyloidosis and infection due to human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 16(5): 733-734. [ Links ]

18. Amarawardena WKMG, Wijesundere A, Manohari HAD. Amyloidosis associated with HIV infection. Ceylon Medical Journal 2013; 58: 128-129. [ Links ]

19. Pett SL, Kelleher AD, Emery S. Role of interleukin-2 in patients with HIV infection. Drugs 2010; 70(9): 1115-1130. [ Links ]

20. Jensen LE, Whitehead AS. Regulation of serum amyloid A protein expression during the acute-phase response. Biochem J 1998; 3: 489-503. [ Links ]

21. Montero LC, Egocheaga AA, Quirós JFB, Pérez MV. Nefropatía VIH y amiloidosis. Med Clin 1997; 108(209): 797-798. [ Links ]

22. Lanjewar DN, Ansari MA, Schetty CR, Maheshwari MB, Jain P. Renal lesions associated with AIDS – an autopsy study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 1999; 42(1): 63-68. [ Links ]

23. Atta MG, Choi MJ, Longenecker JC et al. Nephrotic range proteinuria and CD4 count as noninvasive indicators of HIV-associated nephropathy. AM J Med 2005; 118(11): 1288. [ Links ]

24. Szczech LA, Gupta SK, Habash R et al. The clinical epidemiology and course of the spectrum of renal diseases associated with HIV infection. Kidney Int 2004; 66(3): 1145-1152. [ Links ]

25. Newey C, Odedra BJ, Standish RA, Furmali R, Edwards SG, Miller RF. Renal and gastrointestinal amyloidosis in an HIV-infected injection drug user. Int J STD AIDS 2007; 18(5): 357-358. [ Links ]

26. Nebuloni M, Barbiano di Belgiojoso G, Genderini A et al. Glomerular lesions in HIVpositive patients: a 20-year biopsy experience from Northern Italy. Clin Nephrol 2009; 72(1): 38-45. [ Links ]

Sofia Coelho, MD

Nephrology department, Centro Hospitalar de Setúbal

E-mail: sofiasc17@gmail.com

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: none declared.

Received for publication: May 15, 2017

Accepted in revised form: Aug 11, 2017