Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Portuguese Journal of Nephrology & Hypertension

versão impressa ISSN 0872-0169

Port J Nephrol Hypert vol.32 no.1 Lisboa mar. 2018

EDITORIAL

A new millennium for women and kidney disease

Nicole Pestana, Pedro Vieira, Gil Silva

Nephrology Department, Hospital Central do Funchal

INTRODUCTION

Taking advantage of this years synergy, as World Kidney Day (WKD) and International Womens Day fall on the same day, the theme chosen for WKD 2018 was Kidneys and Womens health, drawing the attention of the nephrology community to the special features of diseases of the kidney as they affect women. When focusing on this subject, we come to see the major gaps in this area of knowledge. On one hand, it is now comprehensively accepted that there are unique biological and behavioral differences resulting in sex/gender variances, albeit mostly in favour of women. However, on the other, despite mounting evidence in multiple medical disciplines, these disparities have not been so well explored in nephrology, and so we try, in this editorial, to review current knowledge n this field.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Acknowledgment of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and its dimension as a public health problem has gained greater importance in the last two decades, due to the recognition of CKDs high morbimortality and high prevalence, ranging from 10-13%1. As for gender differences in CKD epidemiology, it seems that the proportion of women with CKD is higher than that of men, resulting in a 60:40 ratio, whereas in some countries including Portugal, it becomes even more unbalanced with a twofold higher ratio of CKD in women than in men2. This disparity may not accurately denote a higher CKD burden, as it most likely results from a longer life expectancy of women and possibly from a CKD overdiagnosis due to inherent limitations of estimated glomerular filtration rate equations, including lack of correction for body surface area. Hence, when considering CKD progression, most data from population‑based studies show that men have a faster function decline than women. Many theories based on biological differences such as the protective effects of estrogens versus the detrimental effects of testosterone or sociocultural lifestyle disparities have been postulated; however, clinical evidence to support these is rather weak.

Regarding end‑stage renal disease (ESRD) and starting renal replacement therapy (RRT), we observe a male predominance1, in a proportion of 60:40, which, although surprisingly consistent globally, there are still few data to compare the gender difference for the treatment gaps.

Although when considering faster CKD progression in men, one must recognize non‑biological factors, such as access to medical care and personal preference such as greater choice for conservative care among elderly women.

Nevertheless, mortality is higher among men at all levels of predialysis CKD, and, even so, they reach ESRD in a higher proportion than women. Mortality among individuals on RRT is similar for men and women1.

Another unique to women event, pregnancy poses unparalleled obstacles for women as a cause of acute kidney injury in women of childbearing age. Ranging, in developed countries, from hypertensive complications (such as preeclampsia) or other thrombotic microangiopathies to other obstetric complications (including septic abortions, placental abruption, and intravascular disseminated coagulation) more common in developing countries. All of which may lead to subsequent CKD, but quantification of this risk is not known.

Turning to access to transplantation, the perception that this is lower for women than for men dates back more than three decades. This may be due to patient preference, gender selection bias by health‑care personnel, or socioeconomic reasons. However recent studies based on developed countries evidenced declining disparities, after adjusting the analysis of transplantation rates in men and women for the preformed antibodies. The sensitizing event developed during pregnancy leads to women having more preformed antibodies, which justifies 14% fewer deceased kidney allocation in women1. In terms of living donation, apart from the predictable disadvantage of preformed antibodies, particularly in spousal donations, the differences remain mostly speculative.

WOMENS SPECIFICITIES: PREGNANCY IN CKD, DIALYSIS AND TRANSPLANTATION

Where do women with CKD stand in terms of pregnancy?

CKD affects up to 6% of women of childbearing age in high‑income countries, and is estimated to affect 3% of pregnant women3. The complex alterations of the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑ovarian axis together with the effects of inflammatory disease are the major reasons for compromised fertility in women with CKD. Nevertheless, the chance of pregnancy is high enough so that in daily practice one needs to prevent it if it is not desired or approach it in a multidisciplinary manner if it does occur. The perception of the intimate association between kidney disease and pregnancy reflects the adverse outcomes from early stages of CKD until later stages of kidney function during pregnancy and postpartum.

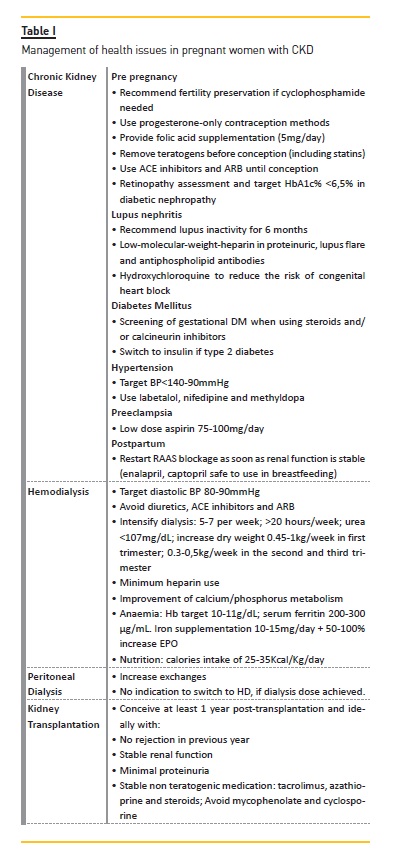

Lindheimer et al demonstrated that women presenting pre‑pregnancy serum creatinine ≥2.8mg/dL were associated to pregnancy problems in about 86% and only 76% had successful obstetric outcomes. Forty percent of these women progressed to ESDR within 1 year3. Notably, baseline hypertension and proteinuria are the most important modulators of pregnancy‑related risks. While not all causes of kidney disease are major determinants of worsening of kidney disease during pregnancy, diabetic nephropathy and lupus nephritis have been linked to more adverse outcomes. Equally so, the negative effect of kidney disease on pregnancy can be shown by extremely high rates of caesarean section (70%), preterm delivery <37 (89%) and <34 (44%) weeks, small gestational age <10% (50%) and <5% (25%) percentiles as well as increased needs for neonatal intensive care unit (70%)4. Pregnancy per se is a potential timeframe for the initial diagnosis of CKD and kidney biopsy seems no longer frightening when prompt diagnosis is required, as long as it is performed with controlled blood pressure, normal coagulation and under 30 to 32 weeks pregnancy4. Fortunately, CKD and pregnancy are no longer enemies for women who desire to conceive. While we believe that small impairments of kidney function are linked to successful pregnancies, we agree that baby steps should be taken when counseling a pregnant woman with a more advanced CKD, in terms of managing determined health issues (Table I).

For countless years, being on dialysis and getting pregnant was considered unthinkable among medical community.

However, in the last few decades, great progress has been made in the care of pregnant dialysis patients (and even in pre‑pregnancy stages). These results have been linked to increased dialysis intensity during pregnancy and expanded multidisciplinary care. In fact, since the first successful pregnancy in a patient on hemodialysis (HD) in 1971, the number of successful pregnancies have been increasing over time with a fetal survival gain of ~25% per decade, reaching over 90% in recent years5.

Presently, women who desire to get pregnant are no longer dissuaded from conceiving while on dialysis if there is no forthcoming option for transplantation. Still, awareness of the potential risks must be a mainstay, as even intensively dialyzed women present high rates of preeclampsia (18%) and cervical incompetence (18%), higher than those expected for the general population. Considering the use of the abdominal cavity in peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients, it would seem unreasonable to maintain the pregnant patients in PD. Surprisingly, PD can be continued during pregnancy as long as an increase in the number of exchanges is performed. It should be noted however that a total dialysis dose may not be achieved and this may be linked to decreased overall surface of exchange due to a gravid uterus. As far as fetal outcomes are concerned, a higher rate of low‑weight newborns can be expected (67% in PD versus 31% in HD)6.

Renal transplantation is the desire of most ESRD patients. It has advantages, particularly for women who desire to conceive, as fertility is usually restored in women following transplantation. The first successful pregnancy in a renal transplant recipient occurred in 1958, with an exponential rise in the number of pregnancies over the subsequent decades. Nonetheless, an inferior rate exists when compared to the general population3.

As far as optimal post‑transplantation pregnancy timing goes, there are various unanswered questions. The first concerns optimal pre‑pregnancy kidney function and the second the interplay of the effects of immunosuppressive therapy on both pregnancy and allograft outcomes.

When assessing reduced pregnancy rates in transplanted women, a significant bias may exist concerning improved contraception counseling in this population as well as the employment of teratogenic medication such as first‑line agent mycophenolate mofetil.

WOMEN: KIDNEY AND AUTOIMMUNE DISEASESWhen it comes to autoimmune diseases and their known predominance in females, isnt it time to reform diagnostic and treatment options in this specific population? Autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic scleroderma (SS) play a leading role in public health issues as important causes of morbidity and mortality among women. SLE predominantly affects women of childbearing age (9:1 female‑to‑male ratio with up to 15:1 in peak reproductive years), and lupus nephritis in particular occurs in ~40% of cases6. Unfortunately, even today, in the context of preserved kidney function, the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes is increased in women with active lupus nephritis. While black and Hispanic ethnicity are non‑modifiable risk factors for poor pregnancy outcomes (mostly preterm delivery), proteinuria, hypertension and active disease are all factors that can be managed from a medical perspective through effective preconception management.

Fortunately, the new millennium has brought us new strategies. Tacrolimus is now seen as a new hope when lupus flare develops3, avoiding premature rupture of membranes, preterm delivery, maternal sepsis, and gestational diabetes related to steroid therapy. Similarly, RA also affects predominantly women (4:1 female‑to‑male ratio with a peak incidence between 45 and 55 years old), though, unlike SLE, pregnancy leads to a surprising improvement of the disease. Although SS is reported in a not so pronounced female to male ratio (3:1 to 14:1 with a peak incidence in the fifth and sixth decades) it is additionally linked to the female population.

An equal denominator, estrogens7 are part of the pathophysiology of all these 3 diseases previously described, affecting either positively or negatively the disease. With this in mind, where are we heading to in the new paradigm of estrogen therapies?

CONCLUSION

Women have unique risks for kidney diseases. As in many other areas of scientific knowledge, particular aspects of female kidney disease remain uncharted territory.

There are notable signs of improved management in this field but further efforts should be made in order to achieve full potential outcomes. Turning back to 1975, we found in The Lancet opinion: Children of women with renal disease used to be born dangerously or not at all – not at all if their doctors had their way8. In the new millennium, we urge the need of fully changing this paradigm, as children of women with renal disease should be well born whilst their mothers are assisted by new millennium doctors aiming for new millennium outcomes.

References

1. Carrero JJ, Hecking M, Chesnaye NC, Jager KJ. Sex and gender disparities in the epidemiology and outcomes of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2018;14(3): 151–264 [ Links ]

2. Vinhas J, Gardete‑Correia L, Boavida JM, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and associated risk factors, and risk of end‑stage renal disease: data from the PREVADIAB study. Nephron Clin Pract 2011; 119(1):c35 –40 [ Links ]

3. Webster P, Lightstone L, McKay DB, Josephson MA. Pregnancy in chronic kidney disease and kidney transplantation. Kidney Int 2017;91(5):1047–1056 [ Links ]

4. Hladunewich MA, Bramham K, Jim B, Maynard S. Managing glomerular disease in pregnacy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017;32(1):i48–i56 [ Links ]

5. Manisco G, Potì M, Maggiulli G, Di Tullio M, Losappio V, Vernaglione L. Pregnancy in end‑stage renal disease patients on dialysis: how to achieve a successful deliver. Clin Kidney J 2015;8(3):293–299 [ Links ]

6. Wiles KS, Nelson‑Piercy C, Bramham K. Reproductive health and pregnancy in women with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2018; 14(3):165–184 [ Links ]

7. Ortona E, Pierdominici M, Maselli A, Veroni C, Aloisi F, Shoenfeld Y. Sex‑based Differences in autoimmune diseases. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2016;52(2):205–212 [ Links ]

8. Pregnancy and renal disease. Lancet 1975; 2(7939):801–802 [ Links ]

Correspondence to:

Nicole Pestana, MD

Nephrology Department, Hospital Central do Funchal;

Avenida Luís de Camões nº57, 9004‑514, Funchal

E‑mail: nicole.pest@gmail.com

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: none declared

Received for publication: Mar 26, 2018

Accepted in revised form: Mar 29, 2018