INTRODUCTION

The world is currently in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since a cluster of severe pneumonia were first noted in Wuhan, Hubei province, China, in December 20191, this novel infection has spread rapidly and lethally, with the number of individuals affected by the disease increasing daily. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on March 11th, 2020 and the epidemiological data on this disease has been increasing progressively2.

At the time of writing this article, Spain was one of the countries in the world with the higher reported number of COVID-19 cases, and one of the highest mortality rates. Madrid has been the most affected among the Spanish provinces. In order to estimate the prevalence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-Cov2) infection in the general population, the Ministry of Health conducted a large national sero-epidemiological study, the results of which have been recently published3.

In addition, maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients are very vulnerable to COVID-19, for several reasons. Firstly, due to the fact that they cannot fully respect quarantine since they need to attend long-term threeweek HD sessions. Additionally, when these patients attend HD sessions, they are unable to maintain social distance during the procedure: they maintain physical proximity to medical staff, and other patients, and they regularly use public transport to reach the facilities. Therefore, HD treatment represents a potential risk of COVID-19 transmission4,5. Moreover, MHD patients have a worse prognosis due to the fact that they usually are of older age, have comorbidities, and an immunosuppressive status associated to advanced chronic kidney disease6.

In order to manage these patients, prevention strategies based on the early diagnosis of this disease have been implemented7,8. In this way, the detection of viral RNA by the polymerase chain reaction with reverse transcriptase (Rt-PCR) is currently the reference technique for COVID-19 diagnosis6. However, the high demand for Rt-PCR due to the increased number of suspected COVID-19 cases highly limits its availability.

The aim of this work was to quantify the incidence of COVID-19 based on molecular diagnosis (Rt-PCR), and to explore its correlation with other epidemiological factors in a cohort of dialysis patients from different HD units.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

In March, a group of Spanish nephrologists created a work network to share incidence and experience of the management of this pandemic. The group conducted a national prospective multicenter observational study in a cohort of 2,398 MHD patients.

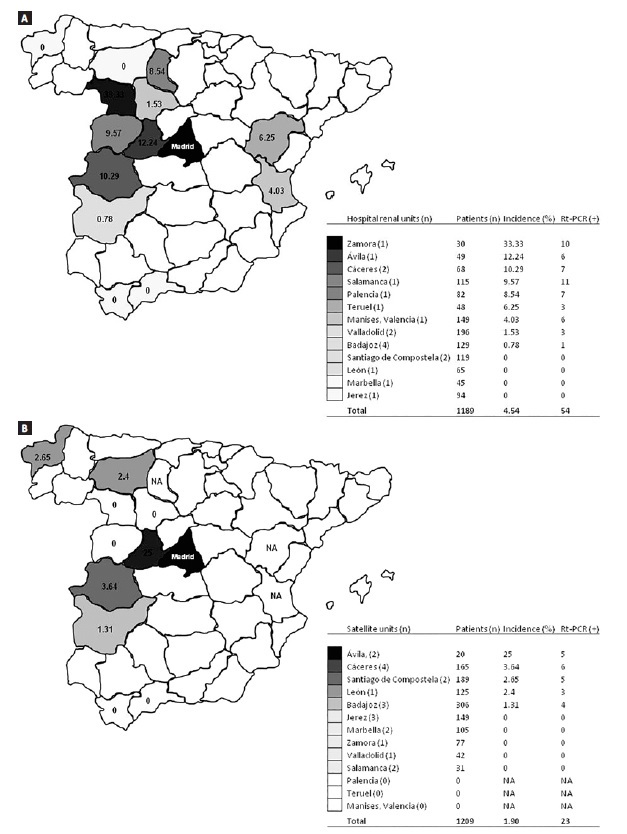

Adult outpatients from 19 hospital renal units and 21 satellite units were included in the study. The names of dialysis facilities were designated according to the city (e.g. Marbella or Santiago de Compostela) or to the Spanish province (if there are dialysis facilities in different cities of the same province; e.g. Cáceres). The location is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Incidence of COVID-19 in the different dialysis facilities and their distance from Madrid, epicenter of the pandemic in Spain

Data collection

The data was collected prospectively March to April 2020. The study was initiated the day Spain began lockdown (March 14th, 2020), and ended 4 weeks after the first pandemic peak (April 28th, 2020).

All the Rt-PCR performed for each patient that participated in this study was recorded. The number of samples and their results were collected daily by the main researcher with an innovative approach: instante messaging via WhatsApp by participants. No personal data was sent, to protect the patient’s privacy. A periodic report with the data from all the units was sent to the participants units to update the nephrologists.

Rt-PCR was performed according to local protocols. First Rt-PCR: in most patients a first and unique determination was made either for symptoms or signs compatible with COVID-19 (fever, cough or dyspnea), or to rule out the disease (due to direct contact with a SARS-CoV-2 positive individual or for undergoing a medical procedure or surgical intervention).

Second Rt-PCR: the test was repeated in patients with negative first Rt-PCR and persistent symptoms or signs.

Moreover, epidemiological data was collected: type of dialysis unit (hospital unit or satellite), general population sero-prevalence (%) of each locality (city or province), and the distance (kilometers) from each diferente HD unit to Madrid, the main epidemiological focus in Spain.

Ethical aspects

The present study respected the ethical recommendations on human studies of the WHO in pandemic situations. The patient’s informed consente was only verbal due to the infection risk involved in obtaining and handling it. In addition, the study was based on the clinical practice recommended by health authorities, which implies that patients’ participation in this study did not represent any risk.

We permanently adopted the local and of scientific societies recommendations that were updated regularly.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was carried out and their values were presented as percentages, means and standard deviation. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the frequency of COVID-19 sero-prevalence in MHD patients and the general population of each location. Correlations were assessed using Pearson’s rank correlation coefficient. Simple regression analysis was also performed to assess univariate associations between the independente (kilometers from Madrid) and independent variables (incidence and seroprevalence of COVID-19). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The analysis was carried out with the GraphPad Prism 5.01 program (GraphPad Software. Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

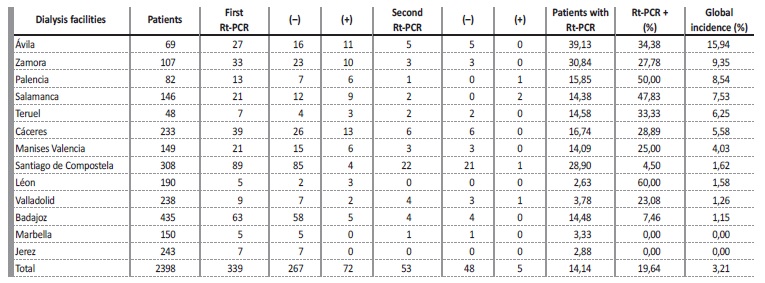

We analyzed 396 Rt-PCR performed in a cohort of 2,398 patients on MCH during the study period (March 14th - April 28th, 2020). 339 patients had only one Rt-PCR performed (First Rt-PCR). 53 received a second determination (Second Rt-PCR), and 4 patients received a third determination

(Third Rt-PCR). Fourteen percent of the prevalent cohort patients were analyzed using Rt-PCR, ranging from 2.6% (León units) to 39.1% (Ávila units). (Table I). It is worth mentioning that 21.2% of the first performed Rt-PCR (72 of 339) and 9.4% of the second performed Rt-PCR (5 of 53) were positive. There was no positive sample in the 4 patients who underwent Rt-PCR for a third time. Overall, the positive samples were 19.4% of the total (77 of 396). (Table I).

Table 1 Rt-PCR performed in the different dialysis facilities. The number and result of the samples obtained in the first determination (first Rt-PCR), and in those patients whose sample was repeated (second Rt-PCR) are shown, as well as the percentage of patients studied by Rt-PCR, and the percentage of positive samples.

The incidence of COVID-19 in the cohort was 3.2%. Again, there was a marked incidence variability depending on the location of the HD units.

No case was detected in units in Marbella or Jerez de la Frontera, but reached 15.9% in units in Ávila. (Table I and Figure 1). There were 19 hospital and 21 satellite units included in the study, where 1,189 (49.6%) and 1,209 (51.4%) patients were dialyzed, respectively. The incidence of COVID-19 in the hospital units (Figure 2a) was significantly higher (p = 0.0003) than the incidence observed in the satellite units (Figure 2b): 4.5% and 1.9% respectively.

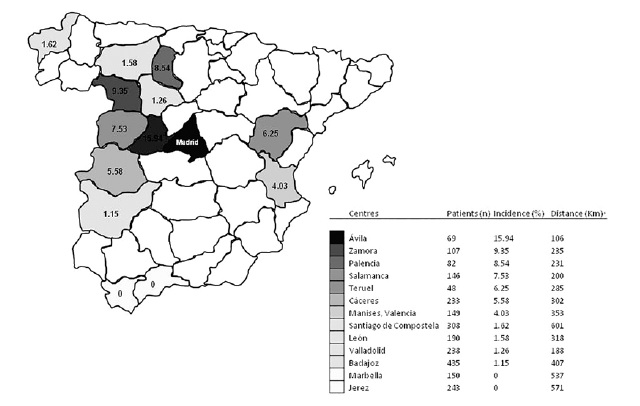

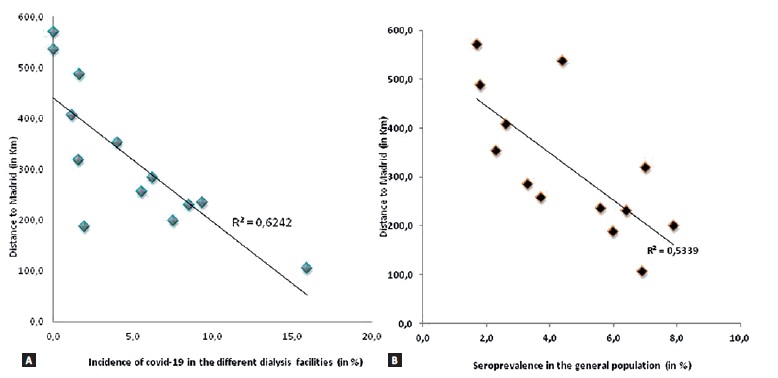

According to Pearson’s correlation and simple linear regression analysis, a positive and significant correlation between the incidence of COVID-19 in HD units and their proximity to Madrid was observed (R2 = 0.6242 p = 0.0013) (Figure 3a). Thus, a higher incidence of COVID-19 was observed in cities or provinces closer to Madrid. Conversely a lower or null incidence of this disease was observed in those areas which were farthest from Madrid (Figure 1). The same positive and significant correlation was also observed between the rate of antibodies in the general population (national study of seroprevalence)3 of each studied province and its proximity to Madrid (R2 = 0.5339 p = 0.0046) (Figure 3b).

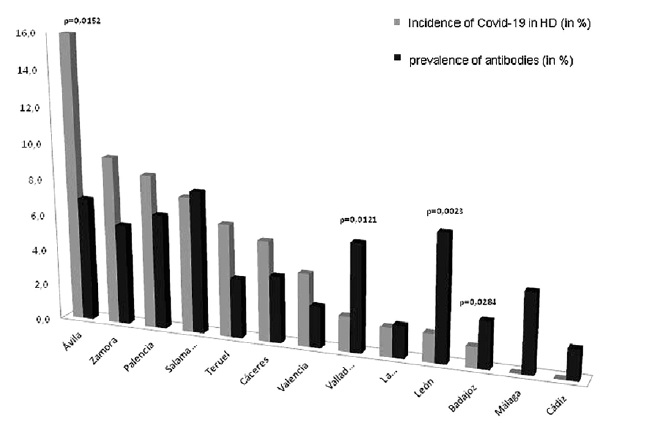

Finally, no clear relationship was observed between the percentage of seroprevalence in the general population3 and the COVID-19 incidence in its HD units. Thus, there were provinces such as León, Valladolid or Badajoz, with a significantly lower COVID-19 incidence in their HD units compared to their general population seroprevalence (p <0.05; Fisher exact test). This phenomenon was even more evident in cities such as Marbella (Málaga) or Jerez de la Frontera (Cádiz), where no positive cases were reported in their HD units. On the contrary, there were provinces such as Zamora, Palencia, Teruel, Cáceres or Valencia, where COVID-19 incidence in their HD units was higher than the percentage of seroprevalence in their general population. This difference was particularly high in the province of Ávila (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Correlation between the incidence of COVID-19 and the distance to Madrid from the dialysis facilities (Fig. 3a) and correlation between the seroprevalence in the general population (in each province) and the distance to Madrid (Fig. 3b)

DISCUSSION

A cohort of 2,398 MCH patients from 40 dialysis units participated in this prospective study. Fourteen percent of the cohort was analyzed by Rt-PCR, finding a global COVID-19 incidence of 3.2%. This number can be interpreted as lower than expected, because MCH patients are particularly vulnerable to respiratory pathogens and severe pneumonia, due to the effects of uremic toxins, impaired cellular and humoral immune functions, and the long-term protein malnutrition9,10. In fact, in previous SARS pandemics, there was a higher morbidity in MHD patients compared to the general population11. Initial data from Wuhan, China, showed an incidence of 14.3% (90 out of 627 MHD)12 and 16.1% (37 among 230 MHD)13.

However, when suspected cases were confirmed by Rt-PCR, the incidence dropped to 1.7% (109 out of 6,377 MHD) or 2.9 (7 out of 244 MHD),14and 2.2% (154 out of 7,151 MHD)15. In an environment closer to ours, preliminary data from Lombardy in Italy, the epicenter of the pandemic in this country, there was an incidence of 5% (301 out of 6,000 MHD)16.

However, this figure dropped to 3.5% when global country data was analyzed (1,093 out of 30,821 MHD)17. Very similar data was documented in the French registry, where the overall COVID-19 incidence was 3.3% (1,621 of 48,669)18. In our country a COVID-19 incidence of 2.94 (14 out of 476 MHD) was found in dialysis units in Valencia19 and 3.63 (21 out of 220 MHD)20 in Barcelona. To sum up, the data in the present study was similar to that reported in our environment and slightly higher than the reported from China.

In our study, there was considerable variability in the incidence of SARSCoV- 2 infection in dialysis units which ranged from 0 to 16%. This data was similar to that reported in Italy (0 to 17%)17 or in France (0 to 10%)18. Although these records17,18 showed a clear relationship between incidence and latitude, a close correlation with the proximity to Madrid, the main epidemic focus in Spain, was observed in our study (R2 = 0.6242 p = 0.0013).

In fact, dialysis units in Madrid showed a much higher incidence than that reported in our study: 11.1% (23 out of 208 MHD)21, from 12.8% (36 out of 282 MHD)22, and 18.9% (17 out of 90 MHD)23. It is difficult to speculate about the true explanation of this correlation. It is possible that the local rate of infection spread and the burden that occurred in Madrid at the beginning of the pandemic was the main cause, as occurred in other countries17,18.

However, our findings are descriptive and other reasons (e.g. multiple existing connections with Madrid or possible social links between the HD units closest to Madrid) require further investigation.

We also found a higher incidence of COVID-19 in hospital units than in satellite units (4.5% vs. 1.9% p = 0.0003). This data, although logical, has not been reported in other studies12-23. It could be due to the fact that, during the pandemic, hospitals devoted themselves almost exclusively to treating patients infected with COVID-19, which would explain a higher incidence of infection in their HD units. Unlike the French registry18, we did not find a clear parallel in the incidence in dialysis units and the seroprevalence observed in the general population3.

Even though we performed a large number of PCR tests during the study period (n=396), we recognize that only 14% of the patients were checked. This fact, together with the high percentage of asymptomatic positive patients23, means that the incidence of cases could be higher than the confirmed ones. It should also be recognized that the great impact that the pandemic had on the general population, the limited number of tests available, and the sample size (approximately 2,400 patients) limited the use of Rt-PCR in our study. Despite this, our data was similar to those reported by other studies in similar settings17-24.

Mortality was not collected in the present study due to three reasons: more than half of the patients were awaiting the evolution (favorable or death) at the end of data collection; there were patients who died with a positive Rt-PCR, but whose death cannot be assumed to be caused by SARS-CoV-2, and, finally, there were patients who died with symptoms highly suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 but whose Rt-PCR was negative. However, according to the Spanish national registry, the mortality was 23% in the studied period24.

This study has certain weaknesses and some strengths. The distribution of dialysis units was not homogeneous or representative of na entire territory or country. In contrast, most of the study units were part of a randomized clinical trial25, joined by others. In addition, the number of patients (n=2,398), tests performed (n=396) and units participating in the study (n=40) were large enough for the obtained data to be considered. Furthermore, our COVID-19 incidence could be considered “real”, since our patient data were reported in real time, both those patients confirmed by Rt-PCR and the number of MCH patients, crucial data for calculating the real incidence of the disease. Another limitation is that there were no Madrid units included in the cohort.

This is relevant, due to the fact that the incidence of these facilities was greater than that observed in our study21-23. However, the inclusion of any Madrid unit would have not represented the rest of HD units from this community.

This study was carried out through a working group that shared experiences and knowledge among its members. This allowed the heads of the units to make decisions and exercise essential leadership to control this type of situation26.

CONCLUSIONS

• Our study showed a relatively low incidence of COVID-19 among MHD, contrary to what might have been feared; this incidence was similar to that observed in other studies.

• As in the general population, the epidemic did not evenly affect all the studied units, with a higher incidence observed in the units closest to Madrid and in hospital HD units than in satellite units.